by Adam Hartung | Jan 12, 2022 | Boards of Directors, Leadership, Medical, Strategy, Trends

I was happy to end 2021 on a very high note. Kaiser Health Network interviewed me on the future of pharmacies, based on my historically accurate forecasts for retailers. READ MORE I was delighted when this went semi-viral, being picked up by Yahoo!News, Salon, Washington Post and about a dozen other publications.

I’ve had a nearly 2 decade relationship with Vistage and its global network of CEOs. I was delighted to be interviewed about the best short-term and long-term goal setting process, giving all Vistage members my insights for success and how to use their planning processes to build a road to greater profitable growth.

READ MORE I’m looking forward to working with more Vistage groups and individual members in 2022 as their ambition for success continues growing.

I kicked off 2022 with a live webcast interview with International Market & Competitive Intelligence

magazine, hosted by its Chief Editor Rom Gayoso. As the changing world remains in fast-shifting overdrive leaders are increasingly looking for insights about the future. I’m delighted more keep asking how they can use my 30+ years of trend tracking to help them find the right stars to follow. Let me know by email or phone if you’d like to talk about how I can help your business grow stronger every year, despite the seeming chaos around us. Here’s my

interview with Rom Gayoso.

Lesson – You are either growing, or you are dying. There is no “maintenance, status quo.”

For 2022, Spark Partners is offering its Master Class on strategic planning and innovation for HALF OFF! That’s right, for just $495 you can get this 28 module course that shows you how to identify and follow trends, then build plans that leverage those trends for faster, more profitable growth. There’s no similar tool in the marketplace. A year in the making, this course provides an overview of the process I’ve used to build successful forecasts for investors and business leaders across companies of all sizes.

https://www.sparkpartners.com/business-master-class-think-innovation-course

Respond to this email and I can arrange your limited time discount to get started building a stronger, more successful organization.

Are you on “cruise control” running your business?

Ask yourself, Are you trying to defend and extend what you’ve always done? Or are you meeting unmet customer needs, helping customers to grow and in turn growing yourself? If you’re the former, get ready for a rude awakening.

Did you see the trends, and were you expecting the changes that would happen to your demand? It IS possible to use trends to make good forecasts, and prepare for big market shifts. If you don’t have time to do it, perhaps you should contact us, Spark Partners. We track hundreds of trends, and are experts at developing scenarios applied to your business to help you make better decisions.

TRENDS MATTER. If you align with trends your business can do GREAT! Are you aligned with trends? What are the threats and opportunities in your strategy and markets? Do you need an outsider to assess what you don’t know you don’t know? You’ll be surprised how valuable an inexpensive assessment can be for your future business. Click for Assessment info. Or, to keep up on trends, subscribe to our weekly podcasts and posts on trends and how they will affect the world of business at www.SparkPartners.com

Give us a call or send an email. [email protected] 847-726-8465.

by Adam Hartung | Jan 16, 2020 | Boards of Directors, Defend & Extend, Leadership, Software, Web/Tech

People who follow my speaking and writing – including my over 400 Forbes columns – know that I preach the importance of growth. Successful organizations are agile – and agility is the sum of learning + adaptability. Smart organizations are constantly looking externally, gathering data, learning about markets and shifts – then structured to adopt those learnings into their business model and adapt the organization to new market needs.

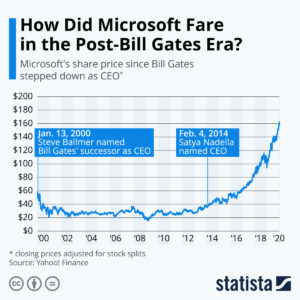

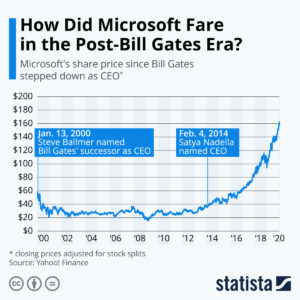

Steve Ballmer was the antithesis of agility. For his entire career he knew only that  Windows and Office made all the money at Microsoft. So he kept investing in Windows and Office. He failed at everything else. False starts in phones, tablets, gaming – products came and went like ice cream cones on a hot August day. Ballmer laughed at the very notion of the iPhone ever being successful – while simultaneously throwing away $7.2B buying Nokia. Then there was $8.5B buying Skype. $400M buying the Borders Nook. Those were ridiculous acquisitions that just wasted shareholder money. To Ballmer, Microsoft’s future relied on maintaining Windows and Office.

Windows and Office made all the money at Microsoft. So he kept investing in Windows and Office. He failed at everything else. False starts in phones, tablets, gaming – products came and went like ice cream cones on a hot August day. Ballmer laughed at the very notion of the iPhone ever being successful – while simultaneously throwing away $7.2B buying Nokia. Then there was $8.5B buying Skype. $400M buying the Borders Nook. Those were ridiculous acquisitions that just wasted shareholder money. To Ballmer, Microsoft’s future relied on maintaining Windows and Office.

So as the market went mobile, Ballmer kept over-investing. He spent billions launching Windows 8, which I predicted was obviously going to fail at growing the Windows market as early as 2012. And it was easy to predict that Win8 tablets were going to be a bust when launched in 2012 as well. But Ballmer was “all-in” on Windows and Office. He was completely locked-in, and unwilling to even consider any data indicating that the PC market was dying – effectively driving Microsoft over a cliff.

It was not hard to identify Steve Ballmer as the worst CEO in America in 2012. When Ballmer took over Microsoft it was worth $60/share. He drove that value down to $20. And the company valuation was almost unchanged his entire 14 years as CEO. He remained locked-in to trying to Defend & Extend PC sales, and it did Microsoft no good. But when the Board replaced Ballmer with Nadella the company moved quickly into growth in gaming, and especially cloud services. In just 6 years Nadella has improved the company’s value by 400%!!!

Success is NOT about defending the past. Success IS about growth. Don’t be locked in to what worked before. Focus on what markets want and need – learn how to understand these needs – and then adapt to giving customers new solutions. Don’t make the mistakes of Ballmer – be a Nadella to lead your organization into growth opportunities!

by Adam Hartung | Jun 20, 2018 | Boards of Directors, Growth Stall, Investing, Manufacturing, Strategy

An American epoch has ended. General Electric was part of the first ever Dow Jones Index in 1896. When the Dow Jones Industrial Average was formed in 1907 GE was a participant. GE has been the only company to remain on the index. All other original companies long ago completely disappeared.

GE did so well because its leadership had been able to constantly change the company to keep it relevant, and growing. During the century prior to hiring Jeff Immelt as CEO GE went from light bulbs to generating electricity and making all kinds of electrical infrastructure equipment, electric locomotives, mainframe computers, medical equipment, computer services, financial services, entertainment…. The list is very long.

Although not all GE CEOs were great, the Board was able to place CEOs in office who could sense market shifts and make good decisions. GE leadership thoughtfully analyzed markets, and made investment decisions to sell businesses that were not growing. And they made investment decisions to invest in trends which created growth. One of the best of these was Jack Welch, who developed the nickname “Neutron Jack” for his willingness to jettison businesses that were not growing and leading their industry, while willingly investing in entirely new growth markets where trends showed high rates of return like financial services and entertainment – wildly “non-industrial” markets.

But CEO Immelt was completely tone-deaf to the outside world. He was wholly unable to understand how to lead a team that could make good investments. Instead under Immelt’s leadership GE over-invested in historical products where they were losing advantage but trying to “keep up.” Selling businesses that were growing but faced stiff competition, rather than investing in growth. And refusing to invest in new external growth opportunities that could keep revenues increasing – and drive a higher GE market capitalization.

All the way back in 2009 I pointed out that GE was in a Growth Stall, and had only a 7% chance of consistently growing at 2%. I warned investors. At the time I said GE had to go all-out on a growth strategy, or things would turn ugly. But a lot of investors, employees – and apparently the Board of Directors – were ready to blame the Growth Stall on the economy. And blame it on Welch, who had been gone for 8 years. And say GE was lucky Immelt saved the company from bankruptcy with a loan from Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway.

Say what? Saved the company? Why did Immelt, and the Board, let GE get into such terrible shape? It was time to replace the CEO, not double down on his failed strategy.

Six years ago, May, 2012, I published in Forbes “5 CEOs that Should Have Already Been Fired.” At the time I said Immelt was the 4th worst CEO in America. I cited the 2009 column, and pointed out things really weren’t any better in 2012 than in 2009. That column had well over 1million reads. There was no way GE’s board was not aware of the column, and the realization that Immelt was a horrible CEO.

The Board of #3 (Walmart) fired Mike Duke. And the Board of #1 (Microsoft) fired Steve Ballmer. There is no real board at #2 Sears (which will file bankruptcy soon enough) because the CEO is also the largest shareholder (via his hedge fund) and he controls all board decisions. He should have fired himself, but had too much ego. But the board of GE – well it did nothing. Even though GE almost went bankrupt under Immelt, and its value was being destroyed quarter after quarter it left him in place.

I revisited the performance of these five CEOs and their companies in August, 2014 and reminded hundreds of thousands of readers – which I’m sure included GE’s Board of Directors – that company revenues had declined every year since 2009. And this string of failures had caused the company’s value to decline by 2/3. Yet, the board did nothing to replace this horrific CEO.

By March, 2017 I was so exasperated I finally titled my column “GE Needs a New Strategy and a New CEO.” Again, I detailed all the things that went wrong. It took 7 more months before the Board pushed Immelt out. But the new CEO failed to offer a better strategy, continuing to promote the notion of selling businesses to raise cash to “fix” the broken businesses – without identifying any growth strategy at all.

The only thing that can “fix” GE – save it from being dismembered and sold off – is a growth strategy. I offered how the new CEO could undertake this effort in October, 2017. But the Board, still wholly incompetent, still isn’t listening. Nobody should be surprised that GE is now removed from the Dow, and the new CEO is clearly without a clue how to find a path back to relevancy.

Too bad for investors, employees, suppliers, customers and the communities where the GE businesses reside. This didn’t have to happen. But due to an incompetent Board of Directors, which did nothing to properly govern an incompetent CEO, it did. And there’s little doubt it won’t be long before GE meets the same end as DuPont.

by Paul F | Nov 30, 2017 | Boards of Directors, Trends

As a Fellow with NACD, I have spoken at meetings and met members around the US. I’ve heard the comments echoing the sentiments of this year’s study. I’ve written at length about how to reduce the risk and how to see unexpected trends while there is still time to react.

Excerpt from NACD website:

This year’s survey offers great insight into how directors and boards view the next 12 months. Which major business trends do they expect will have the greatest impact on their companies? What are the areas where they hope to improve board performance next year? Which topics are the ones on which directors want to spend more time during board meetings? In addition, we assess how boards are currently engaging with management on the increasingly complex challenge of formulating strategy and drill down on the growing board imperative of corporate-culture oversight.

With permission from NACD, you can download this year’s study here:

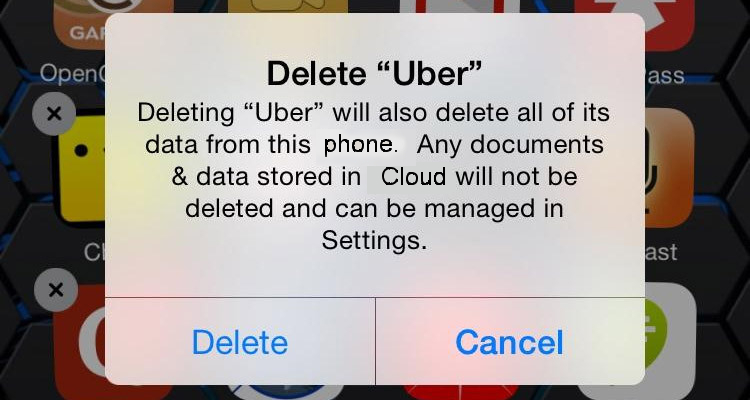

by Adam Hartung | Aug 24, 2017 | Boards of Directors, Leadership, Transportation

We learned last week that Jeff Immelt is a front-runner to be the next CEO of Uber. There are many reasons to be concerned about this possibility.

Uber has received nothing but bad news for a while now:

Amidst these scandals, Uber’s big investors are

writing down the value of their Uber holdings by 15%. After pushing the board for new leadership, and restructuring, it appears investors are losing faith in the company.

This puts the board in the hot seat. Investors want a new CEO that will eliminate the scandals. They want stability at the company. Reeling from so much bad news, they want someone atop the organization who will “right the ship” with “a steady hand on the tiller” so they can regain confidence. Amidst the turmoil, and the need to please investors, an executive who spent 35 years at GE, and over a decade in the top job, probably sounds like a good candidate. He’s known as a stable guy, numbers-focused, genteel, well-schooled (Harvard MBA) and above all “seasoned.”

But the stakes are incredibly high. Picking the wrong person at this moment could well lead to a horrible long-term outcome. While meeting short-term needs sounds like the #1 goal right now, for Uber to succeed means putting someone in the CEO job who can guide the tech company through a decade or more of tough decisions in a fast-paced market. Other boards have suffered horribly from making this decision hurriedly and poorly.

Remember the CEO turmoil at Yahoo:

- Yahoo was an early leader on the web, first in search, content distribution, on-line sales and advertising under CEO Tim Koogle from 1995-2001.

- Due to controversies (remember when he sold Nazi memorabilia?) he was replaced by proven media exec (25 years at Warner Brothers) Terry Semel from 2001-2007. He’s the one who missed the opportunities to buy Google and Facebook.

- Worried the company needed more pizzazz to catch leapfrogging competitors, the board brought back founder Jerry Yang for 17 months (2007-2008).

- When sales didn’t improve the board brought in brash, blunt speaking Carol Bartz, CEO of Autodesk, to turn around the company (2009-2011.) After months of cost-cutting but no sales improvement, she was gone.

- In January 2012 the board hired the President of Paypal, Scott Johnson, as CEO. But 5 months later he was fired for lying on his resume.

- Amidst a need to find someone to lead the company long-term, in 2012 the board hired Google darling Marissa Mayer as CEO. She left when Yahoo dissolved.

Or how about Twitter:

- From 2007-2008 Jack Dorsey was the founder who drove growth and early funding.

- Dorsey was replaced by Evan Williams (2008-2010) who was to supply a steadier, more seasoned hand at the top.

- Looking to grow and go public, the board replaced Williams with Dick Costolo (2010-2015). Although the IPO went well, lack of investor enthusiasm led to stock weakness.

- In 2015 Costolo was replaced by the returning Dorsey. He supposedly would rejuvenate the company. Since his return the stock has dropped about 50% amidst concerns regarding insufficient user and revenue growth.

But this is not a new problem in tech. Remember the CEO litany at Apple:

- Apple’s first CEO (1977-1981) was Michael Scott from National Semiconductor, brought in to support the inexperienced Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak. But he was unable to get along with the founders, and built a reputation of firing those he didn’t like.

- Mike Markkula, Apple’s early investor and 3rd employee, replaced Scott as CEO from 1981-1983.

- Hoping to put someone with a better pedigree, more big-company experience and a steadier hand in the top job, Markkula hired John Sculley (former Pepsi CEO) to Apple’s top job in 1983. Markkula agreed with Sculley to fire the mercurial Jobs in 1985. Sculley remained CEO until 1993, when he was removed as Apple lost the war with Microsoft for corporate desktops and sales tanked. Sculley, the much heralded, experienced corporate leader, ended up ranked the 14th worst CEO of all time by Conde Nast Portfolio.

- The board replaced him with insider Michael Spindler (1993-1996) who tried to sell Apple to IBM, Sun and Philips, but failed.

- Spindler was replaced by Gil Amelio (1996-1997) former CEO of National Semiconductor, who was considered the kind of mature, dedicated leader Apple needed. As Apple shares slumped to all time lows, he bought Jobs-owned NeXt.

- Jobs (CEO 1997-2011) succeeded in convincing the Board to fire Amelio. Jobs subsequently fired the board. The rest is well documented.

Jeff Immelt is no Steve Jobs

Clearly, Uber’s board needs to find a Steve Jobs. And by all accounts, for all his skills, Jeff Immelt is NOT a Steve Jobs. During his tenure as CEO of GE things might have been boring, but the company also lost a third of its revenues, and a third of its market cap. After more than a decade of stagnation, Immelt was forced out. It is hard to imagine he is the right person to guide Uber, a high-tech company in a fast changing marketplace filled with techie employees who want a culture of rapid growth with opportunities to build fortunes in company equity. To maintain its value Uber needs to keep growing at 20%+/year, and Immelt has no experience creating that sort of revenue success.

So what should the board look for? Last summer Chris Zook and James Allen of Bain & Co. published their treatise on how to lead high growth companies The Founder’s Mentality – How To Overcome the Predictable Crises of Growth . I interviewed Chris Zook last year, and he offered great insights that would be incredibly valuable for the Uber board now:

- Being great is hard. Most companies are focused on going from mediocre to good, far from going from good to great. Uber is the undisputed champion in ride-sharing today. The leader must be unassailable as a visionary. Someone who understands how to build a GREAT company. The last CEO may have been problematic, but he built Uber – a tremendous business success. The new leader has to be on a par with other leaders of companies considered great by the employees (and investors) or he will not be respected, and there will be more problems, not fewer.

- “Next Generation CEOs” (as Zook calls them) are flexible thinkers who can figure out the hidden core, and build on it. The incoming CEO of Marvel realized its core was story telling, not comics, and directed the company into films and other growth venues. Jobs realized Apple was more than the Mac, and tied the company to offering easy-to-use products that fit emerging mobile needs. Uber’s next CEO has to go deeper than the scandals and obvious business model to understand what made Uber the leader, and expand on that nugget of strength to keep the company growing, and beating competitors. (Software for the gig economy? Time sharing assets?)

- Blockages are what kill companies. Most big-company CEOs are great at creating organizational blockages to create stability. They tend to be numbers first, customers and technology second. They put in place middle managers with the primary job of stopping behaviors that could be problematic. They instill “no” in order to stop mistakes. Do not ever forget the Sculley/Apple experience. The next Uber CEO has to be willing to operate in a culture with few barriers, direct access from the bottom employee to the CEO, and the ability to move quickly to deal with problems rather than attempting to eliminate the possibility of problems.

- The CEO has to be willing to make big bets. Today markets move fast. Leaders have to project trends, understand where customers are headed and place big bets that keep the company on top. Think about Bezos pushing Amazon to implement Prime, and buying Whole Foods. Think about Jobs directing Apple’s massive bet on mobile and the iPod. Think about Reed Hastings making the big bet at Netflix on streaming, and more recently on original content. To be a successful leader today of a growth company is not for the timid, nor for those who want to make small, progressive bets over time. It requires vision, the willingness to make big bets and the ability to convince your employees, your board of directors and your investors to buy into that bet.

The Uber board is apparently a bit tired of their search. Perhaps that’s because they aren’t looking for the right kind of person. As Mr. Zook told me, you rarely find leaders with a “Founder’s Mentality” through a search firm. You find them already competing, offering insight, doing new things in situations where the competition is intense. Like Jobs was at Pixar, and NeXt.

The right leader is out there – we’ve seen the type in companies mentioned here, and others like Google and Facebook. But you have to search for them intensely. What seems very, very unlikely is that Mr. Immelt is “the right man for the job” at Uber today.

by Adam Hartung | Apr 21, 2017 | Boards of Directors, Investing, Leadership

When I was young, IBM dominated computing. In the tech world, when comparing platforms, everyone said, “Nobody ever got fired for buying IBM.” IBM was a standout role model for sales success, product leadership and investor returns.

Now, not so much. IBM’s stock fell almost 5% on Wednesday after the company reported “lackluster” results. For the week IBM lost about $20 per share – almost 12%. Quarterly revenue last quarter fell 3%, making 20 consecutive quarters of declining revenue for the once-dominant behemoth and Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA) component.

CEO of IBM Ginni Rometty (Photo by Neilson Barnard/Getty Images for New York Times)

The stock is still up from January 2016 lows of $125, and you might think this pullback is a buying opportunity. But you would be wrong. For long-term investors the stock has fallen from about $194 when CEO Ginni Rometty took control to the recent $160 — a 17.5% decline over five years. And that is after spending $9 billion on payouts (mostly share buybacks) to prop up the stock!

But because of its long-term “growth stall” the odds are almost a certainty things will continue to worsen for IBM.

(c) Adam Hartung and Spark Partners

(c) Adam Hartung and Spark Partners

Growth Stalls are Deadly Accurate Predictors of Future Value Declines

When a company has two consecutive declining quarters of revenue or earnings, or two consecutive quarters of revenue or earnings lower than the previous year, that company is in a “growth stall.” After stalling, 93% of companies will struggle to consistently grow a mere 2%. Seventy percent will lose more than half their market cap.

I made this same

call, to not own IBM, in May 2014. Then IBM had registered a stall on both the quarter-to-quarter metric, and on the year-over-year quarterly metric. IBM was clearly in a “growth stall” and showed no signs of turning around its fortunes. Now IBM has failed to grow quarterly revenue for

five years!Supported by the company PR and investor relations departments, optimists will claim there is reason to think things will improve. For example, in September 2015 IBM executive John Kelly predicted that Watson would be the next “huge engine” for growth. Today the Cognitive Computing segment that is Watson is about the same size it was then. In fact none of the five IBM segments are showing strong growth.

The reason a “growth stall” is such an accurate predictor of future bad results is its ability, in a very simple way, to describe when a company falls out of step with its customers/marketplace. The market went one way — in this case to mobile apps, mobile devices and cloud computing — while the company remained in outdated businesses and launched competitive offerings too late to catch the early market makers. At IBM, Cognitive has not become a big new market, while the historical Business Services and Systems segments keep shrinking, and Cloud Services is simply out-gunned by competitors like Amazon.

Rometty should be replaced by someone from outside IBM.

Meanwhile, the CEO keeps her job and even achieves pay raises! In 2016 IBM’s stock had dropped 36% since Rometty took the CEO position, yet the board of directors payed out the max bonus, leading the LA Times to headline “IBM’s CEO Writes a New Chapter on How To Turn Failure Into Wealth.” Last year the company share price bounced of its lows, but still far below what it was when she took the job, and in 2017 the Board increased her bonus from 2016! And the CEO will be granted a long-term pay incentive of $13.3 million in June (to be paid in 2020).

Like Immelt at GE, Rometty should be fired. If there were an updated list of the “5 Worst CEO’s Who Should Have Already Been Fired,” CEO Rometty surely deserves to be on it. And a new leader needs to implement an entirely new strategy if IBM is ever to regain its lost glory.

IBM’s stock may bounce around quite a bit. It’s shareholder base is very large. And really big investors, like pension funds and mutual funds, are very slow to dump their positions. But, eventually, everyone realizes that a shrinking company is not a value creation company, and they keep selling shares into any sign of strength. Big investors eventually recognize when a Board is unwilling to actually help lead a company, and unwilling to face down a bad CEO and replace her with someone more competently able to turn around a perennial terrible performer. So they start selling before the bottom falls out — like Sears and AT&T after they were removed from the DJIA.

There’s a lot more downside potential for IBM’s valuation.

In IBM’s case, the shares are at about $195 when the first data indicating a growth stall were evident (Q3 2012). They then peaked at $213 in March 2013. And it has been an ugly ride since. he “bounce” in 2016 from $125 to $180 was actually the best selling opportunity since September 2014 (just after I made the call to get out). At $160, IBM is down about 18% since the growth stall started (largely due to share buybacks) and revenues have kept dropping. According to “growth stall” analysis there is a 69% probability IBM’s shares will fall to $85 per share — or less — before the company fails, or starts a true, long-term recovery under new leadership.

by Adam Hartung | Mar 30, 2017 | Boards of Directors, Disruptions, Investing, Leadership

(Photo: CEO of Amazon.com, Inc. Jeff Bezos, TOMMASO BODDI/AFP/Getty Images)

Amazon.com is now worth about the same as Berkshire Hathaway. Amazon has had an amazing run-up in value. The stock is up 17% year to date, and 46% over the last 12 months. By comparison, Berkshire has risen 3.1% this year and Microsoft has risen 5.6% —while the S&P 500 is up 5.8%. Due to this greater value increase, Jeff Bezos has become the second richest man in the world, jumping past Warren Buffett while Bill Gates remains No. 1.

Obviously, it wouldn’t take much of a slip in Amazon, or a jump in Berkshire, to reverse the positions of the companies and their CEOs. But it is important to recognize what is happening when a barely profitable company that sells general merchandise, technology products (Kindles, Fires and Echos) and technology services (AWS) eclipses one of the most revered financial minds and successful investment managers of all time.

Warren Buffett (Photo by Paul Morigi/Getty Images for Fortune/Time Inc)

Berkshire Hathaway was a financial pioneer for the Industrial Era. Warren Buffett bought a down-and-out textile company and created enormous value by turning it into a financial powerhouse. At the time America, and the world, was still in the Industrial Revolution. Making things – manufacturing – was the biggest industry of all. Buffett and his colleagues recognized that capital for these companies was deployed very inefficiently. Often too much capital was invested in poor ways, while insufficient capital was invested in good opportunities. If Berkshire could build a capital base it could deploy that capital into high-return opportunities, and make above-average rates of return.

When Buffett started his magical machine he realized that capital was often in short supply. Companies had to ration capital, unable to build the means of production they desired. Banks were unwilling to lend when they perceived any risk, even when the risk was not that great. Simultaneously investment banks were highly inefficient. The industry was unwilling to support companies prior to going public, often uninterested in taking companies public, and poor at allocating additional capital to the highest return opportunities. By the time you were big enough to use an investment bank you really didn’t need them to raise capital – they just organized the transactions.

This inefficiency in capital allocation meant that an investor with capital could create tremendous gains by deploying it in high return opportunities that often had minimal risk – or at least risk that could be offset with other investments.

Berkshire Hathaway was a big winner at mastering finance during the industrial era. By putting money in the right place, at the right time, tremendous gains could be made. Berkshire didn’t have to be a manufacturer, it could make a higher rate of return by understanding how to deploy capital to industrial companies in a marketplace where capital was rationed. In other words, give people money when they need it and Berkshire could generate outsized returns.

It was a great strategy for supporting companies in the Industrial Age. And a great way to make money when capital was hard to come by.

But the world has changed. Two important things happened First, capital became a lot easier to acquire. Deregulation and a vast expansion of financial services led to a greater willingness to lend by banks, larger secondary markets for bank-originated products that carried risk, the creation of venture capital and private equity firms willing to invest in riskier opportunities, and a dramatic growth in investment banking globally making it far easier to go public and raise equity. Capital became vastly more available, and the cost of capital dropped dramatically.

This made finding opportunities for outsized returns just based on investing considerably more difficult. And thus every year it has become harder for Berkshire Hathaway to find investment opportunities that exceed market rates of return. Berkshire isn’t doing poorly, but it now competes in a world of many competitors who have driven down returns for everyone. Thus, Berkshire’s returns increasingly move toward the market norm.

The Industrial Era is dead — usher in the Information Era. Second, we are no longer in the Industrial Age. Sometime in the 1990s (economic historians will pin it to a specific date eventually) the world transitioned into the Information Age. In the Information Age assets are no longer worth as much as they previously were. Instead, information has become much more valuable. What a business knows about customers, markets and supply chains is worth more than the buildings, machines and trucks that actually make up the physical economy. The value from having information has become much higher than the value of things — or of providing capital to purchase things.

In the Information Era, few companies have mastered the art of information management better than Amazon.com. Amazon doesn’t succeed because it has great retail stores, or great product inventory or even great computers. Amazon’s success is based on knowing things about markets and its customers. Amazon has piles and piles of data, and Amazon monetizes that information into sales.

By studying customer habits, every time they buy something, Amazon has been able to make the company more valuable to customers. Often Amazon is able to tell a customer what they need before they realize they need it. And Amazon is able to predict the flow of new product introductions, and predict sales for manufacturers with great accuracy. Amazon is able to understand what media customers want, and when they’ll want it. Amazon is able to predict a business’ “cloud needs” before that business knows – and predict the customer’s likely future services needs long before the customer knows.

In the Information Age, Amazon is one of the very, very best information companies out there. It knows how to obtain information, analyze those mounds of “big data” to determine and predict needs, then connect customers with things they want to buy. Being great at information means that Amazon, even with its relatively poor current profits, is positioned to capitalize on its intellectual property for years to come. Not without competition. But with a tremendous competitive lead.

So, how is your portfolio allocated? Are you invested in assets, or information? Accumulating assets is a very hard way to make high rates of return. But creating sales, and profits, out of information is far easier today. The relative change in the value of Amazon and Berkshire is telling investors that it is now smarter to be long information rich companies than asset rich companies.

If you’re long GE, GM, 3M and Walmart how well will you do in an economy where information is more valuable than assets? If you don’t own data rich, analytically intensive companies like Amazon, Facebook, Alphabet/Google and Netflix how would you expect to make above-average rates of return?

And where is your business investing? Are you still putting most of your attention on how you allocate capital, in a world where capital is abundant and cheap? Are you focusing your attention on getting the most out of what you know about markets, customers and suppliers, or just making and selling more stuff? Do you invest in projects to give you insights competitors don’t have, or in making more of the products you have — or launching product version X?

And are you being smart about how you manage your most important information tool — your talented employees? Information is worthless without insight. It is critical companies today do all they can to help employees develop insights, and then rapidly deploy those insights to grow sales. If you spend a few hours pouring over expenses to find dimes, consider letting that activity go in order to spend hours brainstorming how to find new markets and new product opportunities that can generate a lot more revenue dollars.

by Adam Hartung | Oct 21, 2016 | Boards of Directors, Finance, Investing

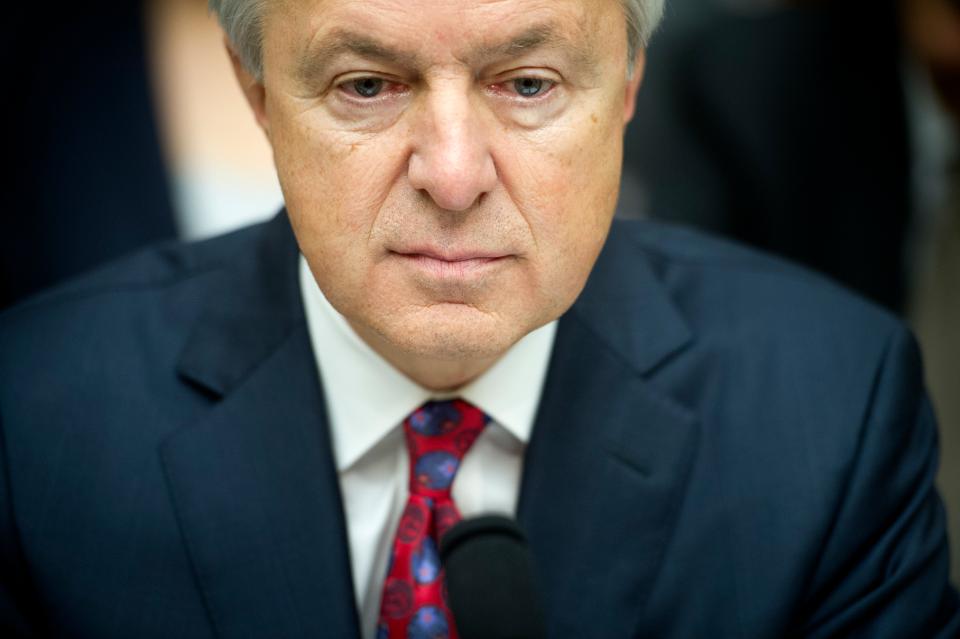

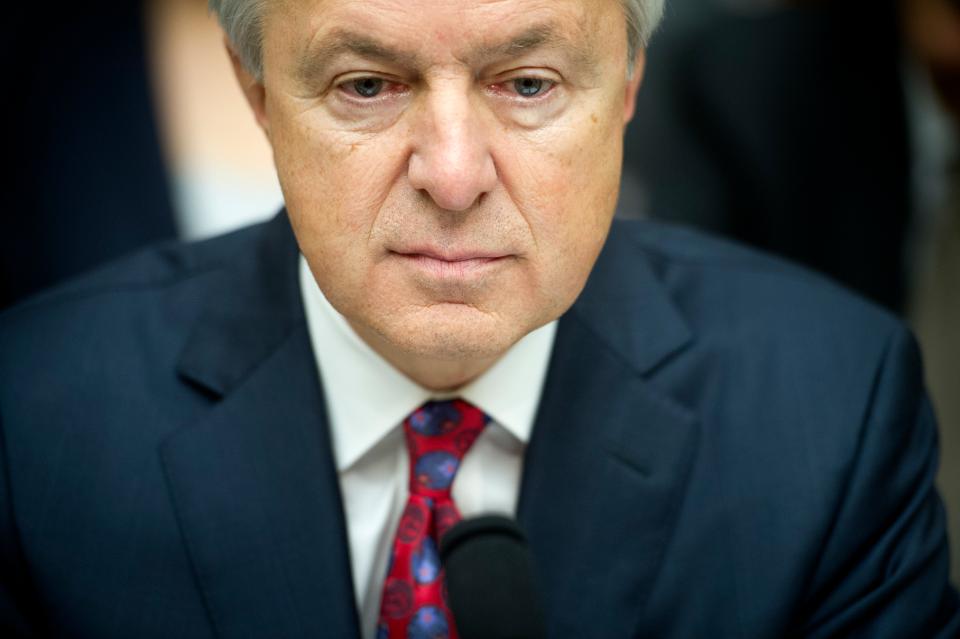

(AP Photo/Cliff Owen, File)

Wells Fargo’s CEO John Stumpf resigned last week. This week he also resigned from the boards of directors at Chevron and Target. For those two roles he was being paid something like $650,000 per year. The interesting question is, why was he on those boards at all? Wasn’t being the CEO and on the board at one of America’s biggest banks a full-time job? After all, he was paid $19.3 million in both 2015 and 2014. You would not have thought he needed a side job to make ends meet.

Which leads to the question, are America’s boards of directors actually staffed with the right people? Ostensibly the board is responsible for governing the corporation. Directors are responsible to insure management makes the right decisions for the long-term best interests of shareholders. And legislators’ have passed multiple laws, such as Sarbanes-Oxley and Dodd-Frank, to allow the regulators, primarily at the SEC (Securities and Exchange Commission), to put real teeth (and enforcement) into directors’ responsibilities.

According to the National Association of Corporate Directors (NACD) a sitting director should do a minimum of 200 hours of work on a board every year. For larger companies committee requirements on top of general board work could easily push this to nearly 300 hours. Thus, Mr. Stumpf should have been doing at least 500 hours of work for Chevron and Target – about 12.5 weeks, or three months. Do you think he actually spent this much time on these roles, given his full time job at Wells Fargo?

This also means that Mr. Stumpf only had nine months to actually work as CEO of Wells Fargo. Maybe that was why he was so unaware of the unethical behavior at the company he led? Why would a board think it is acceptable for a CEO to work only three-fourths of the year? Not many employees have the opportunity to draw full compensation yet take off so much time.

Either Mr. Stumpf wasn’t paying enough attention to Wells Fargo, or he wasn’t paying enough attention to Chevron and Target. Yet, he was being paid very, very handsomely for all those roles. How is that good governance for any one of the three companies?

CEOs serving on additional boards is a bit like electing a governor, who is paid to run the state, and then hearing that the governor is simultaneously going to do part time work for a company or perhaps an agency of a different state. Would any state accept that their governor, state CEO, be allowed to spend three months of every year working side jobs that have nothing to do with being governor? Yet, corporate CEOs regularly take on director roles for other corporations – which in no way benefits their company’s employees, or shareholders. Why?

Further, boards are dominated by sitting or former CEOs. Why? The world moves fast toda, and there are a wealth of skills boards need to effectively govern – far beyond having a room full of CEOs. IT skills, cyber security skills, social media skills, marketing and advertising skills, branding skills, global market skills, intellectual property skills – there is a long list of skills which would greatly improve board diversity, and thereby a board’s ability to govern effectively. So why is hiring so biased toward CEOs? NACD has been asking the same question as it promotes diversity in the boardroom.

Yet, there is one group that is making hay with all that board pay. Former regulators and members of Congress. These people are required to register if they become lobbyists, and they are forced to wait a year, or more, before they can do work for government contractors. But there is nothing which stops them from joining a board of directors.

There is nothing about being a Congressman or Senator which prepares these people for corporate governance, yet this is common practice as corporations seek ways to find influence without breaking the law. But is it worthwhile to investors to have directors that were prominent in government, but perhaps lacking competency for today’s fast-paced business world? Should a directorship and the compensation be a reward for previous government work – or should it be a position of great importance looking out for the interest of the corporation?

There are currently 64 former members of Congress serving on corporate boards. According to a Harvard and Boston University study, 44% of Senators, and 11% of Congress members have landed corporate board directorships since 1992. Their average compensation, per board, is $350,000. Much better than being in Congress. Especially for a part-time job.

Former Speaker John Boehner and famous cigarette smoker, just joined the tobacco company Reynolds America board – although that may be short-lived as British American Tobacco has offered to acquire Reynolds. Former Majority leader Eric Cantor, who was up for the Speaker job when losing his last election, is now on the board of a Wall Street firm, where he earned $2 million in 2015 for bringing in new business – making him the highest paid director in this group. Former Majority Leader Dick Gephardt has accumulated $10.8 million in director compensation since retiring from Congress in 2005.

Tom Ridge, who was a governor, house member and secretary of Homeland Security – but never a businessperson – raked in $1.4 million in director compensation last year. Even former Congressman and subsequently Secretary of Defense and director of the CIA Leon Panetta made almost $600,000 in director comp last year. These fellows are obviously well connected to government leaders, but do they have a clue about how to effectively implement regulations for corporate audit, compensation or nominating and governance committee roles? Are they hired to apply good governance for investors, or to be rainmakers for the company? Or just to give them a good retirement plan?

Boards exist to protect the rights of shareholders. But do they? The issues at Wells Fargo are an example of how ineffective a board can be at oversight, given that serious problems lasted there for at least five years, and whistle-blowers were terminated for specious reasons. And the Wells board paid the CEO almost $20 million per year, while letting him work a quarter or more of each year as a director for other companies. Hard to see how those directors were doing their job.

When companies do poorly employees, investors and analysts will ask “where was the board?” Increasingly it is clear that more should be asking “who is on the board?” Boards should not be stacked with folks that have lofty titles from previous positions, but which are irrelevant to the needs of that corporation and frequently lacking the qualifications to govern effectively. Target’s investors, for example, probably would have benefited far more by a director that understood networks and cyber crime than paying Mr. Stumpf for his part-time assistance away from Wells Fargo. And with oil prices at generational lows, how did Mr. Stumpf help Chevron prepare for a new world of lower oil demand and greater supplier anxiety in the Middle East?

Sarbanes-Oxley was passed after the outrage that occurred at Enron, where the company completely failed and yet the board said it had no idea of the company’s problems. When America’s financial services industry nearly melted down Dodd-Frank was passed to put more onus on directors to understand the financials and compensation practices of their companies. But, it will most likely take yet more legislation, and more regulation, if investors are to be protected by truly independent directors that are the right people, in the right job, and feel accountable for management oversight and company outcomes.

by Adam Hartung | Oct 13, 2016 | Boards of Directors, Ethics, Finance, Investing, Leadership

SAUL LOEB/AFP/Getty Images

Everyone knows what happened at Wells Fargo. For many years, possibly as far back as 2005, Wells Fargo leaders pushed employees to “cross-sell” products, like high profit credit cards, to customers. Eventually the company bragged it had an industry leading 6.7 products sold to every customer household. However, we now know that some two million of these accounts were fakes – created by employees to meet aggressive sales goals. And, unfortunately, costing unsuspecting customers quite a lot of fees.

We also know that Wells Fargo leadership knew about this practice for at least five years – and agreed to a $190 million fine. And the company apparently fired 5,300

Which begs the obvious question – if management knew this was happening, why did it continue for at least five years?

Let’s face it, if you owned a restaurant and you knew waiters were adding extras onto the bill, or tip, you would not only fire those waiters, but put in place procedures to stop the practice. But in this case we know that management at Wells Fargo was receiving big bonuses based upon this employee behavior. So they allowed it to continue, perhaps with a gloss of disdain, in order for the execs to make more money.

This is the modern, high-tech financial services industry version of putting employees in known dangerous jobs, like picking coal, in order to make more profit. A lot less bloody, for sure, but no less condemnable. Management was pushing employees to skirt the law, while wearing a fig-leaf of protection.

Ignorance is not excuse – especially for a well-paid CEO.

CEO Stumpf’s testified to Congress that he didn’t know the details of what was happening at the lower levels of his bank. He didn’t know bankers were expected to make 100 sales calls per day. When asked about how sales goals were implemented, he responded to Representative Keith Ellison “Congressman, I don’t know that level of detail.”

Really? Sounds amazingly like Bernie Ebbers at Worldcom. Or Jeff Skilling and Ken Lay at Enron. Men making millions of dollars from illegal activities, but claiming they were ignorant of what their own companies were doing. And if they didn’t know, there was no way the board of directors could know, so don’t blame them either.

Does anyone remember how Congress reacted to those please of ignorance? “No more.” Quickly the Sarbanes-Oxley act was passed, making not only top executives but Boards, and in particular audit chairs, responsible for knowing what happened in their companies. And later Dodd-Frank was passed strengthening these laws – particularly for financial services companies. Ignorance would no longer be an excuse.

Where was Wells Fargo’s compliance department?

Based on these laws every Board of Directors is required to establish a compliance officer to make sure procedures are in place to insure proper behavior by management. This compliance officer is required to report to the board that procedures exist, and that there are metrics in place to make sure laws, and ethics policies, are followed.

Additionally, every company is required to implement a whistle-blower hotline so that employees can report violations of laws, regulations, or company policies. These reports are to go either to the audit chair, or the company external legal counsel. If it is a small company, possibly the company general counsel who is bound by law to keep reports confidential, and report to the board. This was implemented, as law, to make sure employees who observed illegal and unethical management behavior, as happened at Worldcom, Enron and Tyco, could report on management and inform the board so Directors could take corrective action.

Which begs the first question “where the heck was Wells Fargo’s compliance office the last five years?” These were not one-off events. They were standard practice at Wells Fargo. Any competent Chief Compliance Officer had to know, after five-plus years of firings, that the practices violated multiple banking practice laws. He must have informed the CEO. He was, by law, supposed to inform the board. Who was the Chief Compliance Officer? What did he report? To whom? When? Why wasn’t action taken, by the board and CEO, to stop these banking practices?

Should regulators allow executives to fire whistle-blowers?

And about that whistle-blower hotline – apparently employees took advantage of it. In 2010, 2011, 2013 and more recently employees called the hotline, even wrote the Human Resources Department and the office of CEO John Stumpf to report unethical practices. Were their warnings held in anonymity? Were they rewarded for coming forward?

Quite to the contrary, one employee, eight days after logging a hotline call, was fired for tardiness. Another was fired days after sending an email to CEO Stumpf alerting him of aberrant, unethical practices. A Wells Fargo HR employee confirmed that it was common practice to find fault with employees who complained, and fire them. Employees who learned from Enron, and tried to do the right thing, were harassed and fired. Exactly 180 degrees contrary to what Congress ordered when passing recent laws.

None of this was a mystery to Wells Fargo leadership, or CEO Stumpf. CNNMoney reported the names of employees, actions they took and the decisively negative reactions taken by Wells Fargo on September 21. There is no way the Wells Fargo folks who prepared CEO Stumpf for his September 29 testimony were unaware. Yet, he replied to questions from Congress that he didn’t know, or didn’t remember, these events – or these people. In eight days these staffers could have unearthed any information – if it had been exculpatory. That Stumpf’s answer was another plea of ignorance only points to leadership’s plan of hiding behind fig leafs.

CEO Stumpf obviously knew the practices at Wells Fargo. So did all his direct reports. And likely two or three levels downs, at a minimum. Clearly, all the way to branch managers. Additionally, the compliance function was surely fully aware, as was HR, of these practices and chose not to solve the issues – but rather hide them and fire employees in an effort to eliminate credible witnesses from reporting wrongdoing by top leadership.

Where was the board of directors? Why didn’t the audit chair intervene?

It is the explicit job of the audit chair to know that the company is in compliance with all applicable laws. It is the audit chairs’ job to implement the Sarbanes-Oxley and Dodd-Frank regulations, and report any variations from regulations to the company auditors, general counsel, lead outside director and chairperson. Where was proper governance of Wells Fargo? Were the Directors doing their jobs, as required by law, in the post Enron, WorldCom, Tyco, Lehman, AIG world?

Should CEO Stumpf be gone? Without a doubt. He should have been gone years ago, for failing to properly implement and enforce compliance. But he is not alone. The officers who condoned these behaviors should also be gone, as should all HR and other managers who failed to implement the regulations as Congress intended.

Additionally, the board of Wells Fargo has plenty of responsibility to shoulder. The board was not effective, and did not do its job. The directors, who were well paid, did not do enough to recognize improper behavior, implement and monitor compliance or take action.

There is a lot more blame here, and if Wells Fargo is to regain the public trust there need to be many more changes in leadership, and Board composition. It is time for the SEC to dig much deeper into the situation at Wells Fargo, and the leaders complicit in failing to follow the intent of Congress.

by Adam Hartung | Jun 19, 2009 | Boards of Directors, Books, Defend & Extend, eBooks, In the Whirlpool, Leadership, Lifecycle, Lock-in, Transportation

Of all the companies that typified America’s rise as an industrial superpower, none was more successful than General Motors.

What happened? Why has it fallen so far? GM at its biggest boasted some 600,000 well-paid employees. It will be left with something like 60,000 after it emerges from bankruptcy. How did that happen? Why did its stock price tumble from $96 per share at its height to 80 cents recently? Why did its market share shrink from one out of every two cars sold to less than one in five last quarter?

And thus begins the new ebook about the fall of GM. In 1,000 words this ebook covers the source of GM’s success – as well as what led to its failure. And what GM could have done differently – as well as why it didn’t do these things. Read it, and share it. Let folks know about it via Twitter. Post to your Facebook page and groups, as well as your Linked-in groups. As markets are shifting the fate of GM threatens all businesses. Even those that are following the best practices that used to make money. Let’s use the story of GM — and the costs its bankruptcy have had on employees, investors, vendors and the support organizations around the industry as well as government bodies — as a rallying cry to help turn around this recession and get our businesses growing again!

Download Fall of GM

(c) Adam Hartung and Spark Partners

(c) Adam Hartung and Spark Partners