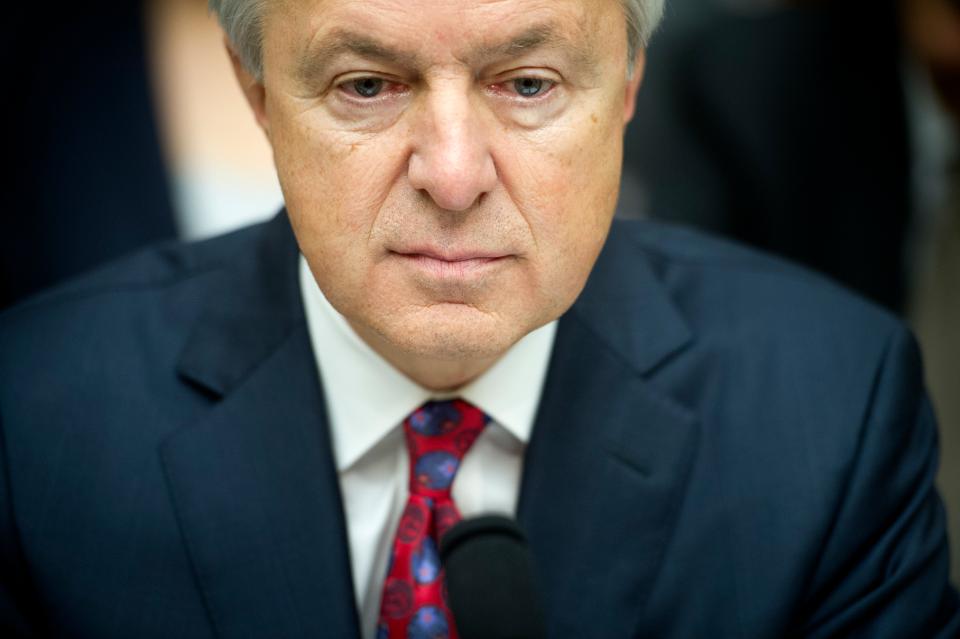

(AP Photo/Cliff Owen, File)

Wells Fargo’s CEO John Stumpf resigned last week. This week he also resigned from the boards of directors at Chevron and Target. For those two roles he was being paid something like $650,000 per year. The interesting question is, why was he on those boards at all? Wasn’t being the CEO and on the board at one of America’s biggest banks a full-time job? After all, he was paid $19.3 million in both 2015 and 2014. You would not have thought he needed a side job to make ends meet.

Which leads to the question, are America’s boards of directors actually staffed with the right people? Ostensibly the board is responsible for governing the corporation. Directors are responsible to insure management makes the right decisions for the long-term best interests of shareholders. And legislators’ have passed multiple laws, such as Sarbanes-Oxley and Dodd-Frank, to allow the regulators, primarily at the SEC (Securities and Exchange Commission), to put real teeth (and enforcement) into directors’ responsibilities.

According to the National Association of Corporate Directors (NACD) a sitting director should do a minimum of 200 hours of work on a board every year. For larger companies committee requirements on top of general board work could easily push this to nearly 300 hours. Thus, Mr. Stumpf should have been doing at least 500 hours of work for Chevron and Target – about 12.5 weeks, or three months. Do you think he actually spent this much time on these roles, given his full time job at Wells Fargo?

Either Mr. Stumpf wasn’t paying enough attention to Wells Fargo, or he wasn’t paying enough attention to Chevron and Target. Yet, he was being paid very, very handsomely for all those roles. How is that good governance for any one of the three companies?

Further, boards are dominated by sitting or former CEOs. Why? The world moves fast toda, and there are a wealth of skills boards need to effectively govern – far beyond having a room full of CEOs. IT skills, cyber security skills, social media skills, marketing and advertising skills, branding skills, global market skills, intellectual property skills – there is a long list of skills which would greatly improve board diversity, and thereby a board’s ability to govern effectively. So why is hiring so biased toward CEOs? NACD has been asking the same question as it promotes diversity in the boardroom.

Yet, there is one group that is making hay with all that board pay. Former regulators and members of Congress. These people are required to register if they become lobbyists, and they are forced to wait a year, or more, before they can do work for government contractors. But there is nothing which stops them from joining a board of directors.

There is nothing about being a Congressman or Senator which prepares these people for corporate governance, yet this is common practice as corporations seek ways to find influence without breaking the law. But is it worthwhile to investors to have directors that were prominent in government, but perhaps lacking competency for today’s fast-paced business world? Should a directorship and the compensation be a reward for previous government work – or should it be a position of great importance looking out for the interest of the corporation?

There are currently 64 former members of Congress serving on corporate boards. According to a Harvard and Boston University study, 44% of Senators, and 11% of Congress members have landed corporate board directorships since 1992. Their average compensation, per board, is $350,000. Much better than being in Congress. Especially for a part-time job.

Former Speaker John Boehner and famous cigarette smoker, just joined the tobacco company Reynolds America board – although that may be short-lived as British American Tobacco has offered to acquire Reynolds. Former Majority leader Eric Cantor, who was up for the Speaker job when losing his last election, is now on the board of a Wall Street firm, where he earned $2 million in 2015 for bringing in new business – making him the highest paid director in this group. Former Majority Leader Dick Gephardt has accumulated $10.8 million in director compensation since retiring from Congress in 2005.

Tom Ridge, who was a governor, house member and secretary of Homeland Security – but never a businessperson – raked in $1.4 million in director compensation last year. Even former Congressman and subsequently Secretary of Defense and director of the CIA Leon Panetta made almost $600,000 in director comp last year. These fellows are obviously well connected to government leaders, but do they have a clue about how to effectively implement regulations for corporate audit, compensation or nominating and governance committee roles? Are they hired to apply good governance for investors, or to be rainmakers for the company? Or just to give them a good retirement plan?

Boards exist to protect the rights of shareholders. But do they? The issues at Wells Fargo are an example of how ineffective a board can be at oversight, given that serious problems lasted there for at least five years, and whistle-blowers were terminated for specious reasons. And the Wells board paid the CEO almost $20 million per year, while letting him work a quarter or more of each year as a director for other companies. Hard to see how those directors were doing their job.

When companies do poorly employees, investors and analysts will ask “where was the board?” Increasingly it is clear that more should be asking “who is on the board?” Boards should not be stacked with folks that have lofty titles from previous positions, but which are irrelevant to the needs of that corporation and frequently lacking the qualifications to govern effectively. Target’s investors, for example, probably would have benefited far more by a director that understood networks and cyber crime than paying Mr. Stumpf for his part-time assistance away from Wells Fargo. And with oil prices at generational lows, how did Mr. Stumpf help Chevron prepare for a new world of lower oil demand and greater supplier anxiety in the Middle East?

Sarbanes-Oxley was passed after the outrage that occurred at Enron, where the company completely failed and yet the board said it had no idea of the company’s problems. When America’s financial services industry nearly melted down Dodd-Frank was passed to put more onus on directors to understand the financials and compensation practices of their companies. But, it will most likely take yet more legislation, and more regulation, if investors are to be protected by truly independent directors that are the right people, in the right job, and feel accountable for management oversight and company outcomes.