by Adam Hartung | Oct 21, 2016 | Boards of Directors, Finance, Investing

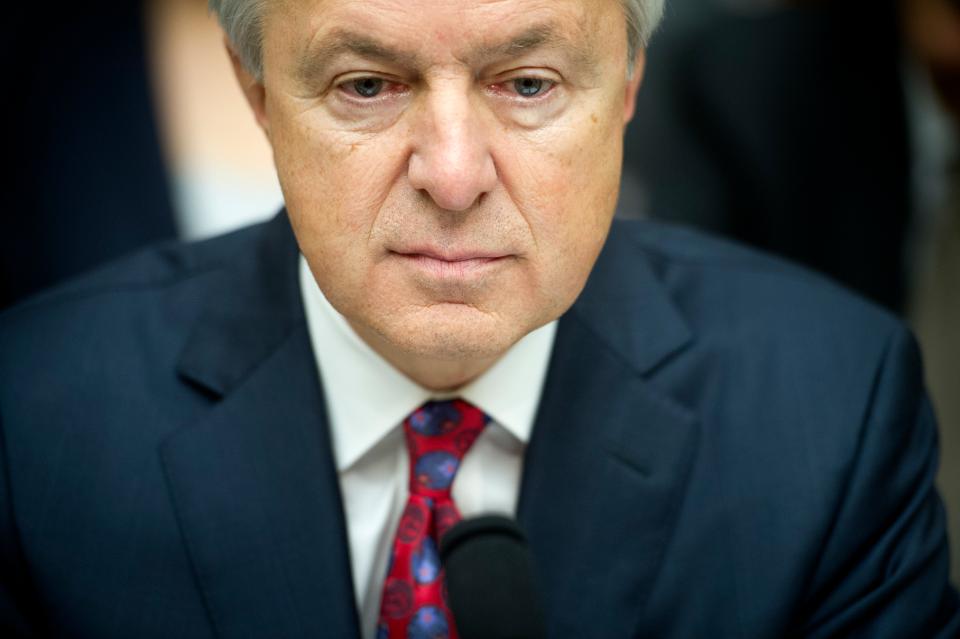

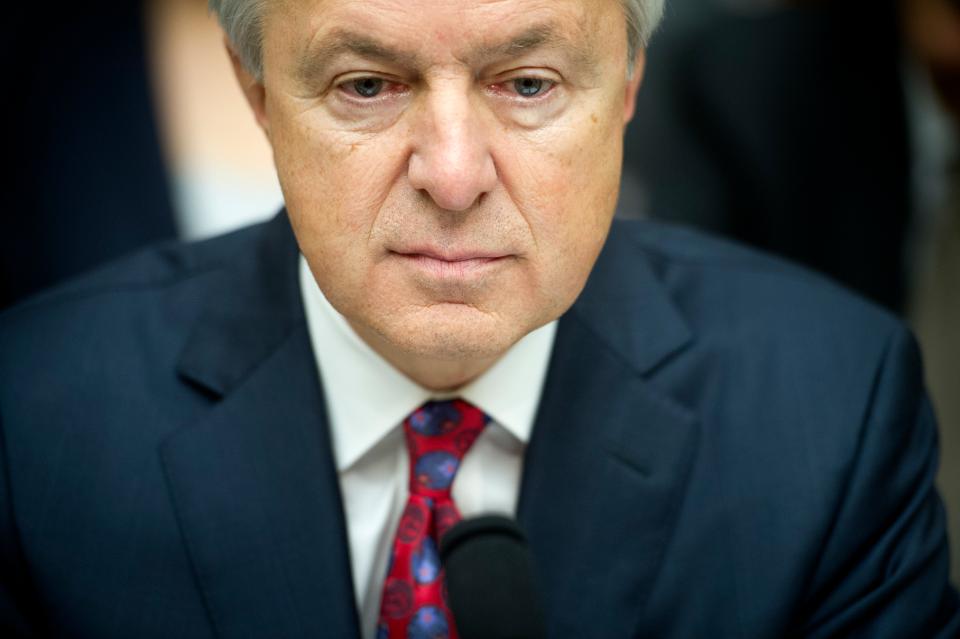

(AP Photo/Cliff Owen, File)

Wells Fargo’s CEO John Stumpf resigned last week. This week he also resigned from the boards of directors at Chevron and Target. For those two roles he was being paid something like $650,000 per year. The interesting question is, why was he on those boards at all? Wasn’t being the CEO and on the board at one of America’s biggest banks a full-time job? After all, he was paid $19.3 million in both 2015 and 2014. You would not have thought he needed a side job to make ends meet.

Which leads to the question, are America’s boards of directors actually staffed with the right people? Ostensibly the board is responsible for governing the corporation. Directors are responsible to insure management makes the right decisions for the long-term best interests of shareholders. And legislators’ have passed multiple laws, such as Sarbanes-Oxley and Dodd-Frank, to allow the regulators, primarily at the SEC (Securities and Exchange Commission), to put real teeth (and enforcement) into directors’ responsibilities.

According to the National Association of Corporate Directors (NACD) a sitting director should do a minimum of 200 hours of work on a board every year. For larger companies committee requirements on top of general board work could easily push this to nearly 300 hours. Thus, Mr. Stumpf should have been doing at least 500 hours of work for Chevron and Target – about 12.5 weeks, or three months. Do you think he actually spent this much time on these roles, given his full time job at Wells Fargo?

This also means that Mr. Stumpf only had nine months to actually work as CEO of Wells Fargo. Maybe that was why he was so unaware of the unethical behavior at the company he led? Why would a board think it is acceptable for a CEO to work only three-fourths of the year? Not many employees have the opportunity to draw full compensation yet take off so much time.

Either Mr. Stumpf wasn’t paying enough attention to Wells Fargo, or he wasn’t paying enough attention to Chevron and Target. Yet, he was being paid very, very handsomely for all those roles. How is that good governance for any one of the three companies?

CEOs serving on additional boards is a bit like electing a governor, who is paid to run the state, and then hearing that the governor is simultaneously going to do part time work for a company or perhaps an agency of a different state. Would any state accept that their governor, state CEO, be allowed to spend three months of every year working side jobs that have nothing to do with being governor? Yet, corporate CEOs regularly take on director roles for other corporations – which in no way benefits their company’s employees, or shareholders. Why?

Further, boards are dominated by sitting or former CEOs. Why? The world moves fast toda, and there are a wealth of skills boards need to effectively govern – far beyond having a room full of CEOs. IT skills, cyber security skills, social media skills, marketing and advertising skills, branding skills, global market skills, intellectual property skills – there is a long list of skills which would greatly improve board diversity, and thereby a board’s ability to govern effectively. So why is hiring so biased toward CEOs? NACD has been asking the same question as it promotes diversity in the boardroom.

Yet, there is one group that is making hay with all that board pay. Former regulators and members of Congress. These people are required to register if they become lobbyists, and they are forced to wait a year, or more, before they can do work for government contractors. But there is nothing which stops them from joining a board of directors.

There is nothing about being a Congressman or Senator which prepares these people for corporate governance, yet this is common practice as corporations seek ways to find influence without breaking the law. But is it worthwhile to investors to have directors that were prominent in government, but perhaps lacking competency for today’s fast-paced business world? Should a directorship and the compensation be a reward for previous government work – or should it be a position of great importance looking out for the interest of the corporation?

There are currently 64 former members of Congress serving on corporate boards. According to a Harvard and Boston University study, 44% of Senators, and 11% of Congress members have landed corporate board directorships since 1992. Their average compensation, per board, is $350,000. Much better than being in Congress. Especially for a part-time job.

Former Speaker John Boehner and famous cigarette smoker, just joined the tobacco company Reynolds America board – although that may be short-lived as British American Tobacco has offered to acquire Reynolds. Former Majority leader Eric Cantor, who was up for the Speaker job when losing his last election, is now on the board of a Wall Street firm, where he earned $2 million in 2015 for bringing in new business – making him the highest paid director in this group. Former Majority Leader Dick Gephardt has accumulated $10.8 million in director compensation since retiring from Congress in 2005.

Tom Ridge, who was a governor, house member and secretary of Homeland Security – but never a businessperson – raked in $1.4 million in director compensation last year. Even former Congressman and subsequently Secretary of Defense and director of the CIA Leon Panetta made almost $600,000 in director comp last year. These fellows are obviously well connected to government leaders, but do they have a clue about how to effectively implement regulations for corporate audit, compensation or nominating and governance committee roles? Are they hired to apply good governance for investors, or to be rainmakers for the company? Or just to give them a good retirement plan?

Boards exist to protect the rights of shareholders. But do they? The issues at Wells Fargo are an example of how ineffective a board can be at oversight, given that serious problems lasted there for at least five years, and whistle-blowers were terminated for specious reasons. And the Wells board paid the CEO almost $20 million per year, while letting him work a quarter or more of each year as a director for other companies. Hard to see how those directors were doing their job.

When companies do poorly employees, investors and analysts will ask “where was the board?” Increasingly it is clear that more should be asking “who is on the board?” Boards should not be stacked with folks that have lofty titles from previous positions, but which are irrelevant to the needs of that corporation and frequently lacking the qualifications to govern effectively. Target’s investors, for example, probably would have benefited far more by a director that understood networks and cyber crime than paying Mr. Stumpf for his part-time assistance away from Wells Fargo. And with oil prices at generational lows, how did Mr. Stumpf help Chevron prepare for a new world of lower oil demand and greater supplier anxiety in the Middle East?

Sarbanes-Oxley was passed after the outrage that occurred at Enron, where the company completely failed and yet the board said it had no idea of the company’s problems. When America’s financial services industry nearly melted down Dodd-Frank was passed to put more onus on directors to understand the financials and compensation practices of their companies. But, it will most likely take yet more legislation, and more regulation, if investors are to be protected by truly independent directors that are the right people, in the right job, and feel accountable for management oversight and company outcomes.

by Adam Hartung | Oct 13, 2016 | Boards of Directors, Ethics, Finance, Investing, Leadership

SAUL LOEB/AFP/Getty Images

Everyone knows what happened at Wells Fargo. For many years, possibly as far back as 2005, Wells Fargo leaders pushed employees to “cross-sell” products, like high profit credit cards, to customers. Eventually the company bragged it had an industry leading 6.7 products sold to every customer household. However, we now know that some two million of these accounts were fakes – created by employees to meet aggressive sales goals. And, unfortunately, costing unsuspecting customers quite a lot of fees.

We also know that Wells Fargo leadership knew about this practice for at least five years – and agreed to a $190 million fine. And the company apparently fired 5,300

Which begs the obvious question – if management knew this was happening, why did it continue for at least five years?

Let’s face it, if you owned a restaurant and you knew waiters were adding extras onto the bill, or tip, you would not only fire those waiters, but put in place procedures to stop the practice. But in this case we know that management at Wells Fargo was receiving big bonuses based upon this employee behavior. So they allowed it to continue, perhaps with a gloss of disdain, in order for the execs to make more money.

This is the modern, high-tech financial services industry version of putting employees in known dangerous jobs, like picking coal, in order to make more profit. A lot less bloody, for sure, but no less condemnable. Management was pushing employees to skirt the law, while wearing a fig-leaf of protection.

Ignorance is not excuse – especially for a well-paid CEO.

CEO Stumpf’s testified to Congress that he didn’t know the details of what was happening at the lower levels of his bank. He didn’t know bankers were expected to make 100 sales calls per day. When asked about how sales goals were implemented, he responded to Representative Keith Ellison “Congressman, I don’t know that level of detail.”

Really? Sounds amazingly like Bernie Ebbers at Worldcom. Or Jeff Skilling and Ken Lay at Enron. Men making millions of dollars from illegal activities, but claiming they were ignorant of what their own companies were doing. And if they didn’t know, there was no way the board of directors could know, so don’t blame them either.

Does anyone remember how Congress reacted to those please of ignorance? “No more.” Quickly the Sarbanes-Oxley act was passed, making not only top executives but Boards, and in particular audit chairs, responsible for knowing what happened in their companies. And later Dodd-Frank was passed strengthening these laws – particularly for financial services companies. Ignorance would no longer be an excuse.

Where was Wells Fargo’s compliance department?

Based on these laws every Board of Directors is required to establish a compliance officer to make sure procedures are in place to insure proper behavior by management. This compliance officer is required to report to the board that procedures exist, and that there are metrics in place to make sure laws, and ethics policies, are followed.

Additionally, every company is required to implement a whistle-blower hotline so that employees can report violations of laws, regulations, or company policies. These reports are to go either to the audit chair, or the company external legal counsel. If it is a small company, possibly the company general counsel who is bound by law to keep reports confidential, and report to the board. This was implemented, as law, to make sure employees who observed illegal and unethical management behavior, as happened at Worldcom, Enron and Tyco, could report on management and inform the board so Directors could take corrective action.

Which begs the first question “where the heck was Wells Fargo’s compliance office the last five years?” These were not one-off events. They were standard practice at Wells Fargo. Any competent Chief Compliance Officer had to know, after five-plus years of firings, that the practices violated multiple banking practice laws. He must have informed the CEO. He was, by law, supposed to inform the board. Who was the Chief Compliance Officer? What did he report? To whom? When? Why wasn’t action taken, by the board and CEO, to stop these banking practices?

Should regulators allow executives to fire whistle-blowers?

And about that whistle-blower hotline – apparently employees took advantage of it. In 2010, 2011, 2013 and more recently employees called the hotline, even wrote the Human Resources Department and the office of CEO John Stumpf to report unethical practices. Were their warnings held in anonymity? Were they rewarded for coming forward?

Quite to the contrary, one employee, eight days after logging a hotline call, was fired for tardiness. Another was fired days after sending an email to CEO Stumpf alerting him of aberrant, unethical practices. A Wells Fargo HR employee confirmed that it was common practice to find fault with employees who complained, and fire them. Employees who learned from Enron, and tried to do the right thing, were harassed and fired. Exactly 180 degrees contrary to what Congress ordered when passing recent laws.

None of this was a mystery to Wells Fargo leadership, or CEO Stumpf. CNNMoney reported the names of employees, actions they took and the decisively negative reactions taken by Wells Fargo on September 21. There is no way the Wells Fargo folks who prepared CEO Stumpf for his September 29 testimony were unaware. Yet, he replied to questions from Congress that he didn’t know, or didn’t remember, these events – or these people. In eight days these staffers could have unearthed any information – if it had been exculpatory. That Stumpf’s answer was another plea of ignorance only points to leadership’s plan of hiding behind fig leafs.

CEO Stumpf obviously knew the practices at Wells Fargo. So did all his direct reports. And likely two or three levels downs, at a minimum. Clearly, all the way to branch managers. Additionally, the compliance function was surely fully aware, as was HR, of these practices and chose not to solve the issues – but rather hide them and fire employees in an effort to eliminate credible witnesses from reporting wrongdoing by top leadership.

Where was the board of directors? Why didn’t the audit chair intervene?

It is the explicit job of the audit chair to know that the company is in compliance with all applicable laws. It is the audit chairs’ job to implement the Sarbanes-Oxley and Dodd-Frank regulations, and report any variations from regulations to the company auditors, general counsel, lead outside director and chairperson. Where was proper governance of Wells Fargo? Were the Directors doing their jobs, as required by law, in the post Enron, WorldCom, Tyco, Lehman, AIG world?

Should CEO Stumpf be gone? Without a doubt. He should have been gone years ago, for failing to properly implement and enforce compliance. But he is not alone. The officers who condoned these behaviors should also be gone, as should all HR and other managers who failed to implement the regulations as Congress intended.

Additionally, the board of Wells Fargo has plenty of responsibility to shoulder. The board was not effective, and did not do its job. The directors, who were well paid, did not do enough to recognize improper behavior, implement and monitor compliance or take action.

There is a lot more blame here, and if Wells Fargo is to regain the public trust there need to be many more changes in leadership, and Board composition. It is time for the SEC to dig much deeper into the situation at Wells Fargo, and the leaders complicit in failing to follow the intent of Congress.

by Adam Hartung | Aug 29, 2016 | Finance, Investing, Politics

(Photo: AP Photo/Andrew Harnik, File)

Last weekend, the Federal Reserve Board’s leadership met to discuss the future of America’s monetary policy. Reports out of that meeting, like reports from all Fed meetings, are long, tedious, and pretty much say nothing. Every analyst tries to interpret from the governors’ statements what might happen next. And because the Fed leadership is so vague, and so academic, the analysts inevitably never guess right.

This bothers a lot of people. There are those who want a lot more “transparency” from the Fed – meaning they want much clearer signals as to what is intended, and usually specifics as to intended actions and a timeline. Because the Fed’s meetings are so cloaked and opaque, some congress members actually want to do away with the Fed, or regulate it a lot more closely.

But for most of us, most of the time, the Fed is pretty much immaterial. When the Fed matters is when there are big swings in the economy, which happen quickly. Then their action is crucial.

Why Small Changes In Interest Rates Don’t Really Matter To Most Of Us

Take the debate right now over a quarter point rise in interest rates. How does this affect most people? Not much. If you have credit card debt, or a car loan, your interest rate is set by the financial institution. And you may hear people talk about zero interest rates, but you know your rate is a whopping amount higher than that. And you know that a quarter point change in the Federal Funds rate will not affect the interest on those loans.

Where you’ll see a difference is in a mortgage. But here, is a quarter point really important?

When I graduated business school in 1982 and wanted to buy my first home the interest rate on an annual, variable rate loan was 18.5%. My first house cost just about $100,000 so the interest was $18,500/year. Today, mortgages are around 3.5%, fixed for anywhere from 3 to 7 years. $18,500 in interest now funds a $525,000 mortgage! If interest rates go to 3.75% – which has many analysts so concerned for the economy – the home value associated with interest of $18,500 is $500,000. Probably within the negotiating range of the buyer.

So you have to borrow a LOT of money for this quarter point to matter. And it does matter to CEOs and CFOs of companies that lead corporations on the S&P 500, or those running huge REITs (Real Estate Investment Trusts) that have enormous debts. But that is not most of us. For most of us, that quarter point difference will not have any impact on our lives.

So Why Do People Pay So Much Attention To The Fed?

The Fed was originally created barely 100 years ago (1913) to try to create a more stable monetary system. But this didn’t work too well in the beginning, which led to the Great Depression. And then, to make matters worse, the conservative bent of the Fed coupled with its fixation on stable interest rates led it to actually cut the money supply as the economy was tanking. This led to a collapse in the value of goods and services, particularly real estate, and the loss of millions of jobs greatly worsening the Great Depression.

It was the depression which really caused economists to focus on studying Fed actions and the economic repercussions. A group of economists, most notably Milton Friedman at the University of Chicago, started saying that the Fed shouldn’t focus on interest rates, but rather on the supply of money. These folks were called “monetarists” and they said interest rates should float, and economists should focus on stable prices.

The 1970s – “Easy Money” Inflation

As we moved into the 1970s, and as Fed Governors kept trying to control interest rates, they found themselves creating more and more money to keep rates low, and in return prices skyrocketed. “Easy money” as they called it allowed ratcheting upward incomes, big pay raises, higher prices for commodities and inflation. Another monetarist leader, Paul Volcker, was named head of the Fed. He rapidly moved to contract the money supply, allowing those 18.5% mortgage rates to develop. Yet, this did stabilize prices and eventually rates lowered, moving down constantly from 1980 to the near zero rates of today for Treasury Bonds and other very large, low risk borrowers.

When the Great Recession hit the Fed leadership, led by Ben Bernanke, remembered the lessons of the Great Depression. As they saw real estate values tumble they were aware of the domino effect this would have on bank failures, and then business failures, just as they had occurred in the 1930s. So they flooded the market with additional currency to keep failures to a minimum, and ease the real estate collapse. This sent interest rates plummeting to the record low levels of the last few years.

Policy Must Address The Current Situation, Not Be Biased By Historical Memories

Yet, people keep worrying about inflation. Those who lived through the 1970s and saw the damage done by inflation are still fearful of it. So they scream loudly about their fear that the last 8 years of monetary ease will create massive future inflation. They want the Fed to be much tighter with money saying that all this cash will someday create inflation down the road. Their view of history is guiding their analysis. Their bias is a fear that “easy money” once caused a problem, so surely it will cause a problem again.

But economists who study prices keep saying that there are currently no signs of price escalation – that wages have not moved up appreciably in a decade, home values are barely where they were a decade ago. Commodity prices are not escalating, in fact many (like oil) are at historically low prices. The dollar is stronger because, relatively speaking, the USA economy is doing better than the rest of the developed world. As long as prices and wages remain without high gains, there is little reason to tighten money, and little reason to feel a higher interest rate is needed.

Further, past monetary increases will not cause future inflation, because monetary policy only affects what is happening now. “Easy money” today can only create inflation today, not in 3 years. And inflation is almost nowhere to be seen.

Ignore Fed “Fine Tuning.” Pay Attention When A Crisis Hits. Otherwise, It’s Up To The Politicians

The big thing to remember is that small changes in policy, such as those that might affect a quarter point change in rates, is “fine tuning” the money supply. And that has pretty nearly no affect on most of us. Where as citizens we should care about the Fed is when big changes happen. We don’t want mistakes like happened in the 1930s, because that hurt everyone. But we do want fast action to deal with a crisis like the falling real estate values and bank collapses that were happening a decade ago.

Remember, it was when the Fed targeted interest rates that the USA economy got into so much trouble. First in the Great Depression, and then in the inflationary 1970s. But when the Fed targeted prices, such as in the 1980s and the mid-2000s, it did exactly what it was created to do, maintain a stable money supply.

So don’t worry about whether analysts think interest rates are going to change a quarter point, or even a half point, in the next year. The big economic question facing us is not a Fed question, but rather “what will it take to increase investment so that we can create more jobs, and provide higher wages leading to a higher standard of living for everyone?” And that is not a question for the Fed to answer. That is up to the economic policy makers in the legislature and the White House.

by Adam Hartung | Aug 26, 2016 | In the Swamp, Investing, Retail, Trends

Photographer: Luke Sharrett/Bloomberg

Walmart is in more trouble than its leadership wants to acknowledge. Investors

need to realize that it is up to Jet.com to turn around the ailing giant. And

that is a big task for the under $1 billion company.

Relevancy Is Hard To Keep – Look At Sears

Nobody likes to think their business can disappear. What CEO wants to tell his investors or employees “we’re no longer relevant, and it looks like our customers are all going somewhere else for their solutions”? Unfortunately, most leadership teams become entrenched in the business model and deny serious threats to longevity, thus leading to inevitable failure as customers switch.

Gallery: “Walmart Goes Small”

In early September the Howard Johnson’s in Bangor, Maine will close. This will leave just one remaining HoJo in the USA. What was once an iconic brand with hundreds of outlets strung along the fast growing interstate highway system is now nearly dead. People still drive the interstate, but trends changed, fast food became a good substitute, and unable to update its business model this once great brand died.

AP Photo/Elise Amendola

Sears announced another $350 million quarterly loss this week. That makes $9 billion in accumulated losses the last several quarters. Since Chairman and CEO Ed Lampert took over, Sears and Kmart have seen same store sales decline every single quarter except one. Unable to keep its customers Mr. Lampert has been closing stores and selling assets to stem the cash drain. But to keep the company afloat his hedge fund, ESL, is loaning Sears Holdings SHLD -2.94% another $300 million. On top of the $500 million the company borrowed last quarter. That the once iconic company, and Dow Jones Industrial Average component, is going to fail is a foregone conclusion.

But most people still think this fate cannot befall the nearly $500 billion revenue behemoth Walmart. It’s simply too big to fail in most people’s eyes.

Walmart’s Crime Problem Is Another Telltale Sign Of Problems In The Business Model

Yet, the primary news about Walmart is not good. Bloomberg this week broke the news that one of the most crime-ridden places in America is the local Walmart store. One store in Tulsa, Oklahoma has had 5,000 police visits in the last five years, and four local stores have had 2,000 visits in the last year alone. Across the system, there is one violent crime in a Walmart every day. By constantly promoting its low cost strategy Walmart has attracted a class of customer that simply is more prone to committing crime. And policies implemented to hang onto customers, like letting them camp out overnight in the parking lots, serve to increase the likelihood of poverty-induced crime.

But this outcome is also directly related to Walmart’s business model and strategy. To promote low prices Walmart has automated more operations, and cut employees like greeters. Thus leadership brags about a 23% increase in sales/employee the last decade. But that has happened as the employment shrank by 400,000. Fewer employees in the stores encourages more crime.

In a real way Walmart has “outsourced” its security to local police departments. Experts say the cost to eliminate this security problem are about $3.2 billion – or about 20% of Walmart’s total profitability. Ouch! In a world where Walmart’s net margin of 3% is fully one-third lower than Target’s 4.6% the money just isn’t there any longer for Walmart to invest in keeping its stores safe.

With each passing month Walmart is becoming the “retailer of last resort” for people who cannot shop online. People who lack credit cards, or even bank accounts. People without the means, or capability, of shopping by computer, or paying electronically. People who have nowhere else to go to shop, due to poverty and societal conditions. Not exactly the ideal customer base for building a growing, profitable business.

Competitors Relentlessly Pick Away At Walmart’s Sales And Profits

To maintain revenues the last several years Walmart has invested heavily in transitioning to superstores which offer a large grocery section. But now Kroger KR -0.5%, Walmart’s no. 1 grocery competitor, is taking aim at the giant retailer, slashing prices on 1,000 items. Just like competition from the “dollar stores” has been attacking Walmart’s general merchandise aisles. Thus putting even more pressure on thinning margins, and leaving less money available to beef up security or entice new customers to the stores.

And the pressure from e-commerce is relentless. As detailed in the Wall Street Journal, Walmart has been selling online for about 15 years, and has a $14 billion online sales presence. But this is only 3% of total sales. And growth has been decelerating for several quarters. Last quarter Walmart’s e-commerce sales grew 7%, while the overall market grew 15% and Amazon ($100 billion revenues) grew 31%. It is clear that Walmart.com simply is not attracting enough customers to grow a healthy replacement business for the struggling stores.

Thus the acquisition of Jet.com.

The hope is that this extremely unprofitable $1 billion online retailer will turn around Walmart’s fortunes. Imbue it with much higher growth, and enhanced profitability. But will Walmart make this transition. Is leadership ready to cannibalize the stores for higher electronic sales? Are they willing to make stores smaller, and close many more, to shift revenues online? Are they willing to suffer Amazon-like profits (or losses) to grow? Are they willing to change the Walmart brand to something different, while letting Jet.com replace Walmart as the dominant brand? Are they willing to give up on the past, and let new leadership guide the company forward?

If they do then Walmart could become something very different in the future. If they really realize that the market is shifting, and that an extreme change is necessary in strategy and tactics then Walmart could become something very different, and remain competitive in the highly segmented and largely online retail future. But if they don’t, Walmart will follow Sears into the whirlpool, and end up much like Howard Johnson’s.

by Adam Hartung | Jun 14, 2016 | Defend & Extend, Investing, Leadership, Web/Tech

Microsoft is buying Linked-In, and we should expect this to be a disaster.

It is clear why Linked-in agreed to be purchased. As revenues have grown, gross margins have dropped precipitously, and the company is losing money. And LInked-in still receives 2/3 of its revenue from recruiting ads (the balance is almost wholly subscription fees,) unable to find a wider advertiser base to support growth. Although membership is rising, monthly active users (MAUs, the most important gauge of social media growth) is only 9% – like Twitter, far below the 40% plus rate of Facebook and upcoming networks. With only 106M MAUs, Linked in is 1/3 the size of Twitter, and 1/15th the size of Facebook. And its $1.5B Lynda acquisition is far, far, far from recovering its investment – or even demonstrating viability as a business.

Even though the price is below the all-time highs for LNKD investors, Microsoft’s offer is far above recent trading prices and a big windfall for them.

But for Microsoft investors, this is a repeat of the pattern that continues to whittle away at their equity value.

Once upon a time, in a land far away, and barely remembered by young people, Microsoft OWNED the tech marketplace. Individuals and companies purchased PCs preloaded with Microsoft Windows 95, Microsoft Office, Microsoft Internet Explorer and a handful of other tools and trinkets. And as companies built networks they used PC servers loaded with Microsoft products. Computing was a Microsoft solution, beginning to end, for the vast majority of users.

Once upon a time, in a land far away, and barely remembered by young people, Microsoft OWNED the tech marketplace. Individuals and companies purchased PCs preloaded with Microsoft Windows 95, Microsoft Office, Microsoft Internet Explorer and a handful of other tools and trinkets. And as companies built networks they used PC servers loaded with Microsoft products. Computing was a Microsoft solution, beginning to end, for the vast majority of users.

But the world changed. Today PC sales continue their multi-year, accelerating decline, while some markets (such as education) are shifting to Chromebooks for low cost desktop/laptop computing, growing their sales and share. Meanwhile, mobile devices have been the growth market for years. Networks are largely public (rather than private) and storage is primarily in the cloud – and supplied by Amazon. Solutions are spread all around, from Google Drive to apps of every flavor and variety. People spend less computing cycles creating documents, spreadsheets and presentations, and a lot more cycles either searching the web or on Facebook, Instagram, WhatsApp, YouTube and Snapchat.

But Microsoft’s leadership still would like to capture that old world. They still hope to put the genie back in the bottle, and have everyone live and work entirely on Microsoft. And somehow they have deluded themselves into thinking that buying Linked-in will allow them to return to the “good old days.”

Microsoft has not done a good job of integrating its own solutions like Office 365, Skype, Sharepoint and Dynamics into a coherent, easy to use, and to some extent mobile, solution. Yet, somehow, investors are expected to believe that after buying Linked-in the two companies will integrate these solutions into the LInked-in social platform, enabling vastly greater adoption/use of Office 365 and Dynamics as they are tied to Linked-in Sales Navigator. Users will be thrilled to have their personal information analyzed by Microsoft big data tools, then sold to advertisers and recruiters. Meanwhile, corporations will come back to Microsoft in droves as they convert Linked-in into a comprehensive project management tool that uses Lynda to educate employees, and 365 to push materials to employees – and allow document collaboration – all across their mobile devices.

Do you really believe this? It might run on the Powerpoint operating system, but this vision will take an enormous amount of code integration. And with Linked-in operated as separate company within Microsoft, who is going to do this integration? This will involve a lot of technical capability, and based on previous performance it appears both companies lack the skills necessary to pull it off. How this mysterious, magical integration will happen is far, far from obvious, or explained in the announcement documents. Sounds a lot more like vaporware than a straightforward software project.

And who thinks that today’s users, from individuals to corporations, have a need for this vision? While it may sound good to Microsoft, have you heard Linked-in users saying they want to use 365 on Linked in? Or that they’ll continue to use Linked-in if forced to buy 365? Or that they want their personal information data mined for advertisers? Or that they desire integration with Dynamics to perform Linked-in based CRM? Or that they see a need for a social-network based project management tool that feeds up training documents or collaborative documents? Are people asking for an integrated, holistic solution from one vendor to replace their current mobile devices and mobile solutions that are upgraded by multiple vendors almost weekly?

And, who really thinks Microsoft is good at acquisition integration? Remember aQuantive? In 2007 Microsoft spent $6B (an 85% premium to market price) to purchase this digital ad agency in order to build its business in the fast growing digital ad space. Don’t feel bad if you don’t remember, because in 2012 Microsoft wrote it off. Of course, there was the buy-it-and-write-it-off pattern repeated with Nokia. Microsoft’s success at taking “bold moves” to expand beyond its core business has been nothing less than horrible. Even the $1.2B acquisition of Yammer in 2012 to make Sharepoint more collaborative and usable has been unsuccessful, even though rolled out for free to 365 users. Yammer is adding nothing to Microsoft’s sales or value as competitor Slack has reaped the growth in corporate messaging.

The only good news story about Microsoft acquisitions is that they missed spending $44B to buy Yahoo – which is now on the market for $5B. Whew, thank goodness that one got away!

Microsoft’s leadership primed the pump for this week’s announcement by having the Chairman talk about investing outside of the company’s core a couple of weeks ago. But the vast majority of analysts are now questioning this giant bet, at a price so high it will lower Microsoft’s earnings for 2 years. Analysts are projecting about a $2B revenue drop for $90B Microsoft next year, and this $26B acquisition will deliver only a $3B bump. Very, very expensive revenue replacement.

Despite all the lingo, Microsoft simply cannot seem to escape its past. Its acquisitions have all been designed to defend and extend its once great history – but now outdated. Customers don’t want the past, they are looking to the future. And no matter how hard they try, Microsoft’s leaders simply appear unable to define a future that is not tightly linked to the company’s past. So investors should expect Linked-In’s future to look a lot like aQuantive. Only this one is going to be the most painful yet in the long list of value transfer from Microsoft investors to the investors of acquired companies.

by Adam Hartung | Jun 9, 2016 | Innovation, Investing, Software, Teamwork

Last week Bloomberg broke a story about how Microsoft’s Chairman, John Thompson, was pushing company management for a faster transition to cloud products and services. He even recommended changes in spending might be in order.

Really? This is news?

Let’s see, how long has the move to mobile been around? It’s over a decade since Blackberry’s started the conversion to mobile. It was 10 years ago Amazon launched AWS. Heck, end of this month it will be 9 years since the iPhone was released – and CEO Steve Ballmer infamously laughed it would be a failure (due to lacking a keyboard.) It’s now been 2 years since Microsoft closed the Nokia acquisition, and just about a year since admitting failure on that one and writing off $7.5B And having failed to achieve even 3% market share with Windows phones, not a single analyst expects Microsoft to be a market player going forward.

So just now, after all this time, the Board is waking up to the need to change the resource allocation? That does seem a bit like looking into barn lock acquisition long after the horses are gone, doesn’t it?

The problem is that historically Boards receive almost all their information from management. Meetings are tightly scheduled affairs, and there isn’t a lot of time set aside for brainstorming new ideas. Or even for arguing with management assumptions. The work of governance has a lot of procedures related to compliance reporting, compensation, financial filings, senior executive hiring and firing – there’s a lot of rote stuff. And in many cases, surprisingly to many non-Directors, the company’s strategy may only be a topic once a year. And that is usually the result of a year long management controlled planning process, where results are reviewed and few challenges are expected. Board reviews of resource allocation are at the very, very tail end of management’s process, and commitments have often already been made – making it very, very hard for the Board to change anything.

And these planning processes are backward-oriented tools, designed to defend and extend existing products and services, not predict changes in markets. These processes originated out of financial planning, which used almost exclusively historical accounting information. In later years these programs were expanded via ERP (Enterprise Resource Planning) systems (such as SAP and Oracle) to include other information from sales, logistics, manufacturing and procurement. But, again, these numbers are almost wholly historical data. Because all the data is historical, the process is fixated on projecting, and thus defending, the old core of historical products sold to historical customers.

Copyright Adam Hartung

Efforts to enhance the process by including extensions to new products or new customers are very, very difficult to implement. The “owners” of the planning processes are inherent skeptics, inclined to base all forecasts on past performance. They have little interest in unproven ideas. Trying to plan for products not yet sold, or for sales to customers not yet in the fold, is considered far dicier – and therefore not worthy of planning. Those extensions are considered speculation – unable to be forecasted with any precision – and therefore completely ignored or deeply discounted.

And the more they are discounted, the less likely they receive any resource funding. If you can’t plan on it, you can’t forecast it, and therefore, you can’t really fund it. And heaven help some employee has a really novel idea for a new product sold to entirely new customers. This is so “white space” oriented that it is completely outside the system, and impossible to build into any future model for revenue, cost or – therefore – investing.

Take for example Microsoft’s recent deal to sell a bunch of patent rights to Xiaomi in order to have Xiaomi load Office and Skype on all their phones. It is a classic example of taking known products, and extending them to very nearby customers. Basically, a deal to sell current software to customers in new markets via a 3rd party. Rather than develop these markets on their own, Microsoft is retrenching out of phones and limiting its investments in China in order to have Xiaomi build the markets – and keeping Microsoft in its safe zone of existing products to known customers.

The result is companies consistently over-investment in their “core” business of current products to current customers. There is a wealth of information on those two groups, and the historical info is unassailable. So it is considered good practice, and prudent business, to invest in defending that core. A few small bets on extensions might be OK – but not many. And as a result the company investment portfolio becomes entirely skewed toward defending the old business rather than reaching out for future growth opportunities.

This can be disastrous if the market shifts, collapsing the old core business as customers move to different solutions. Such as, say, customers buying fewer PCs as they shift to mobile devices, and fewer servers as they shift to cloud services. These planning systems have no way to integrate trend analysis, and therefore no way to forecast major market changes – especially negative ones. And they lack any mechanism for planning on big changes to the product or customer portfolio. All future scenarios are based on business as it has been – a continuation of the status quo primarily – rather than honest scenarios based on trends.

How can you avoid falling into this dilemma, and avoiding the Microsoft trap? To break this cycle, reverse the inputs. Rather than basing resource allocation on financial planning and historical performance, resource allocation should be based on trend analysis, scenario planning and forecasts built from the future backward. If more time were spent on these plans, and engaging external experts like Board Directors in discussions about the future, then companies would be less likely to become so overly-invested in outdated products and tired customers. Less likely to “stay at the party too long” before finding another market to develop.

If your planning is future-oriented, rather than historically driven, you are far more likely to identify risks to your base business, and reduce investments earlier. Simultaneously you will identify new opportunities worthy of more resources, thus dramatically improving the balance in your investment portfolio. And you will be far less likely to end up like the Chairman of a huge, formerly market leading company who sounds like he slept through the last decade before recognizing that his company’s resource allocation just might need some change.

by Adam Hartung | May 27, 2016 | Investing, Mobile, Trends, Web/Tech

Snapchat filed its latest fundraising with the SEC this week. According to TechCrunch, $1.8 billion cash was added to the company, based on a current valuation in the range of $18 billion to $20 billion. Not bad for a company with 2015 revenues of about $59 million. And quite a high valuation for a one-product company that probably nobody who reads this column has ever used – or even knows anything about.

Why is Snapchat so highly valued? Because revenue estimates are for $250 million to $350 million in 2016, and up to $1 billion for 2017. From 50 million daily active users in March, 2014 Snapchat has grown to 110 million users by December, 2015 – so a growth rate of about 50% per year. And this growth has not been all USA, over half the Snapchat users are from Europe and the rest of the world – and the non-USA markets are growing the fastest. Clearly, at 20 times 2017 revenue estimates, investors are expecting dramatic growth in users, and revenue to continue. They anticipate numbers of the magnitude that drove the valuation of Google (over $500 billion) and Facebook ($340 billion).

What is Snapchat? It is the complete opposite of this column. Snapchat is like Twitter only without the text. Of course, most of my readers don’t tweet either, so that may not help. It is a picture or 10 second video messaging app. But, most of my readers don’t use messaging apps either, so that may not be helpful.

Think of texting, only you don’t actually text. Instead you send a picture or short video. That’s it. Pretty simple. Just a way to send your friends pics and videos with your phone – although you can be creative with the pictures and make changes.

People who use Snapchat find it addictive. They may send dozens, or hundreds, of pictures daily. To single friends, groups, or even all their friends – since users can pick who gets the pic.

For many of my readers, this must seem ridiculous. Who would want to send, or receive, several pictures every day from some, or many, of your colleagues and friends?

In 1927 Fred Bernard [trivia] popularized the phrase we use today “

A picture is worth a thousand words.” And today, that is more true than ever. Pictures are replacing words for a vast and growing segment of the population. This is now a very fast growing trend, and it is projected to continue.

“Why is this a trend, and not a fad?” you may ask. The answer goes to the heart of how we use language and images. For thousands of years very few people knew how to read or write. To promulgate information, religious and government leaders would have artists paint images that told the story they wanted spread. These images were then taken from town to town, and people were taught the stories by having someone explain the picture. Then the image could be recalled by the population. It was only after the advent of mass education that using written words became the primary medium for providing information.

Simultaneously, paintings were really expensive. And early photography was expensive. Both mediums were used primarily to memorialize a story, or event. Thus there were relatively few of these images, and they were often treasured, hung on walls or kept in albums for later review. Most of my readers are still stuck in the historical context of thinking of pictures as memorials.

But today images are extremely cheap and easy. Almost everyone has a phone with a camera. So it is easy to take a picture, and it is easy to view a picture. Pictures have become free. And if you can replace a thousand words with one photo, it is far more efficient – and thus from a resource perspective photos are far cheaper (think of how long it takes to write an email as opposed to taking a picture). Given that this flip in resources required has happened, and that the use of mobile technology is growing worldwide and will never revert, we know that this is not s short-term fad, but rather a trend.

Once we communicated by telephone calls. That has dropped dramatically because real-time communication takes a lot more effort to coordinate and implement than asynchronous communication. I can email or text any time I want, and my friend can receive that message when it is convenient for her. And she can choose to respond at her convenience, or not respond at all. Thus email and texting exploded due to the technical capability and their improved economy. Today we have the ability to communicate in pictures or short videos which is even more information dense, and even more economical.

I’m sure many of my readers are saying “well, that may be good for someone else, but not for me.” And that’s good, because you read these columns. But factually, the number of readers is destined to decrease as the number of viewers go up.

There’s a reason every time you open an on-line magazine column you are bombarded by short videos ads. They are more communication dense and they are more successful at capturing attention – even if they do irritate you.

There’s a reason that fewer and fewer people read books, and rely instead on columns like this one to gain insights. And there’s a reason more and more people connect on Facebook rather than sending emails – and rather than sending snail mail (when was the last time you actually mailed someone a birthday card?). Haven’t you ever watched a YouTube video rather than read an instruction manual? While you may not imagine using pictures to replace language, the fact is it is happening with increasing frequency, and lots of people are making the switch. Thus it is a trend that will affect how we do many things for many years into the future.

Snapchat has capitalized on this new trend by making an app which allows you and your friends to communicate far more information a whole lot faster. Rather than interrupting your friends with a phone call (they may be busy right now,) or writing them an email or text message, you can just send them a photo. Have you ever used your phone to photo a label and sent it to someone who’s shopping for you? Or taken a photo of an item so you can find an exact replacement? That same action now can become your way of communicating – of telling your current story. Don’t tell your friends what you had for lunch, just send a photo. Don’t tell your friends you are shopping on Madison Avenue, just take a picture. Pictures are not archives, but rather just a fast, more compact and information filled form of communication.

Snapchat did not discover a new bio-pharmaceutical. It did not create a breakthrough new technology, such as extended battery life. It did not identify a sales opportunity in a far flung country. Nor did it have a breakthrough manufacturing process. Rather, merely by being the leader at implementing an emerging trend Snapchat’s founders have created $20 billion of current value.

Now that you know this trend, what are you going to do so you can capture additional value for your business?

by Adam Hartung | May 20, 2016 | E-Commerce, Investing, Retail, Trends

WalMart announced 1st quarter results on Thursday, and the stock jumped almost 10% on news sales were up versus last year. It was only $1.1B on $115B, about 1%, but it was UP! Same store sales were also up 1%, but analysts pointed out that was largely due to lower prices to hold competitors at bay.

While investors cheered the news, at the higher valuation WalMart is still only worth what it was in June, 2012 (just under $70/share.) From then through August, 2015 WalMart traded at a higher valuation – peaking at $90 in January, 2015. Subsequent fears of slower sales had driven the stock down to $56.50 by November, 2015. So this is a recovery for crestfallen investors the last year, but far from new valuation highs.

Unfortunately, this is likely to be just a blip up in a longer-term ongoing valuation decline for WalMart. And that value will be captured by those who understand the most important, undeniable trend in retail.

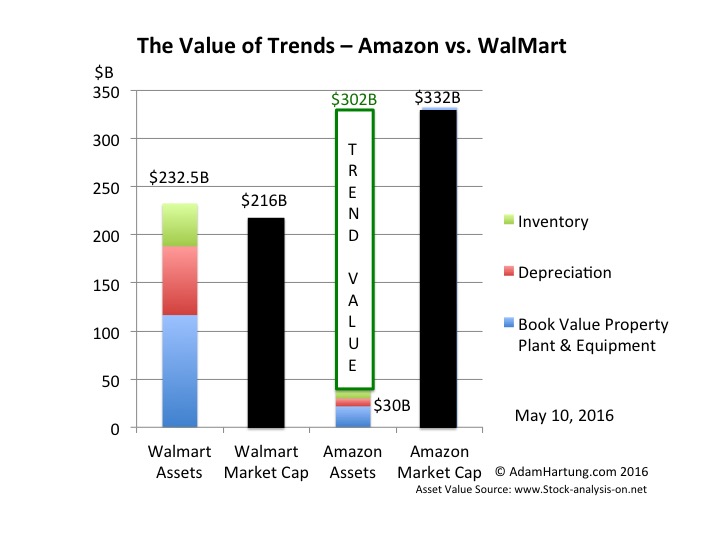

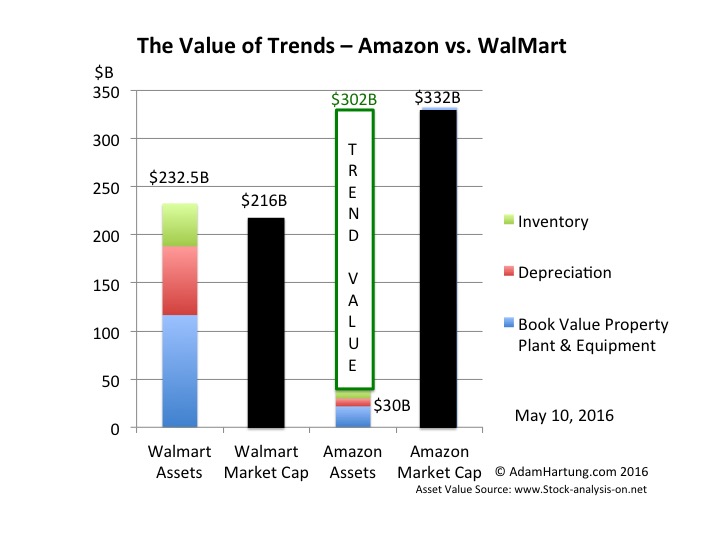

(c) AdamHartung.com Data Sources: Yahoo Finance and www.trend-stock-analysis-on.net

Although the numbers for WalMart’s valuation are a bit better than when the associated chart was completed last week, as you can see WalMart’s assets are greater than the company’s total valuation. This is because the return on its assets, today and projected, are so low that WalMart must borrow money in order to make them overall worthwhile. And the fact that on the balance sheet, at book value, the assets appear to be some $50B lower due to depreciation, and the difference be cost and market value.

This is because WalMart competes almost entirely in the intensely competitive and asset-dense market of traditional brick-and-mortar retail. This requires a lot of land, buildings, shelves and inventory. And that market is barely growing. Maybe 1-2%/year.

Compare t his with Amazon. Amazon has about $30B of assets. Yet its valuation is over $330B. So Amazon captures an extra value of $300B by competing in the asset sparse market of on-line retailing where it needs little land, few buildings, far less shelving and a lot less inventory. And it is competing in a market the Commerce Department says is growing at 15%/year.

The trend to on-line sales is extremely important, as it has entirely different customer acquisition and retention requirements, and very different ways of competing. Amazon understands those trends, and continues to lead its rivals. Today on-line retail is 10.5% of all non-restaurant, non-bar retail. And that 15% growth rate accounts for 60% of ALL the growth in this retail segment. Amazon keeps advancing, growing as fast (or faster) than the industry average, especially in key categories. Meanwhile, despite its vast resources and best efforts WalMart admitted its on-line sales growth is only 7% – half the segment growth rate – and its growth is decelerating.

By understanding this one trend – a very big, important, powerful trend – Amazon captures more value than the current value of ALL the Walmart stores, distribution centers and their contents. With all those assets WalMart can only convince investors it is worth about $200B. With about 13% of the assets used by WalMart, Amazon convinces investors it is worth 33% more than WalMart – over $330B. That’s $300B of value created just by knowing where the market is headed, and how to deliver for customers in that future market.

Yes, Amazon has other businesses, such as AWS cloud services and tech products in tablets, smartphones and smart speakers. But these too (some not nearly as successful as others, mind you) are very much on trends. WalMart once dominated retail technology with its massive computer systems and enormous databases. But WalMart limited itself to using its technology to defend & extend its core traditional retail business via store forecasts, optimized distribution and extensive pricing schemes. Amazon is monetizing its technology prowess by, again, leveraging trends and making its services and products available to others.

How does this apply to you? When someone asks “If you could have anything you want, what would you ask for?” most of us would start with health, happiness, peace and similar intangibles for us, our families and mankind. But if forced to make a tangible selection, we would ask for an asset. Buildings, equipment, cash. Yet, as WalMart and Amazon show us, those assets are only as valuable as what you do with them. And thus, it is more valuable to understand the trends, and how to use assets wisely for greatest value, than it is to own a pile of assets.

So the really important question is “Do you know what trends are going to be important to your business, and are you implementing a strategy to leverage those key trends?” If you are trying to protect your assets, you will likely be overwhelmed by the trend leader. But if you really understand the trends and are ready to act on them, you could be the one to capture the most value in your marketplace, and likely without adding a lot more costly assets.

by Adam Hartung | May 15, 2016 | In the Swamp, Investing, real estate, Retail

Last week Sears announced sales and earnings. And once again, the news was all bad. The stock closed at a record, all time low. One chart pretty much sums up the story, as investors are now realizing bankruptcy is the most likely outcome.

Chart Source: Yahoo Finance 5/13/16

Quick Rundown: In January, 2002 Kmart is headed for bankruptcy. Ed Lampert, CEO of hedge fund ESL, starts buying the bonds. He takes control of the company, makes himself Chairman, and rapidly moves through proceedings. On May 1, 2003, KMart begins trading again. The shares trade for just under $15 (for this column all prices are adjusted for any equity transactions, as reflected in the chart.)

Lampert quickly starts hacking away costs and closing stores. Revenues tumble, but so do costs, and earnings rise. By November, 2004 the stock has risen to $90. Lampert owns 53% of Kmart, and 15% of Sears. Lampert hires a new CEO for Kmart, and quickly announces his intention to buy all of slow growing, financially troubled Sears.

In March, 2005 Sears shareholders approve the deal. The stock trades for $126. Analysts praise the deal, saying Lampert has “the Midas touch” for cutting costs. Pumped by most analysts, and none moreso than Jim Cramer of “Mad Money” fame (Lampert’s former roommate,) in 2 years the stock soars to $178 by April, 2007. So far Lampert has done nothing to create value but relentlessly cut costs via massive layoffs, big inventory reductions, delayed payments to suppliers and store closures.

Homebuilding falls off a cliff as real estate values tumble, and the Great Recession begins. Retailers are creamed by investors, and appliance sales dependent Sears crashes to $33.76 in 18 months. On hopes that a recovering economy will raise all boats, the stock recovers over the next 18 months to $113 by April, 2010. But sales per store keep declining, even as the number of stores shrinks. Revenues fall faster than costs, and the stock falls to $43.73 by January, 2013 when Lampert appoints himself CEO. In just under 2.5 years with Lampert as CEO and Chairman the company’s sales keep falling, more stores are closed or sold, and the stock finds an all-time low of $11.13 – 25% lower than when Lampert took KMart public almost exactly 13 years ago – and 94% off its highs.

What happened?

Sears became a retailing juggernaut via innovation. When general stores were small and often far between, and stocking inventory was precious, Sears invented mail order catalogues. Over time almost every home in America was receiving 1, or several, catalogues every year. They were a major source of purchases, especially by people living in non-urban communities. Then Sears realized it could open massive stores to sell all those things in its catalogue, and the company pioneered very large, well stocked stores where customers could buy everything from clothes to tools to appliances to guns. As malls came along, Sears was again a pioneer “anchoring” many malls and obtaining lower cost space due to the company’s ability to draw in customers for other retailers.

To help customers buy more Sears created customer installment loans. If a young couple couldn’t afford a stove for their new home they could buy it on terms, paying $10 or $15 a month, long before credit cards existed. The more people bought on their revolving credit line, and the more they paid Sears, the more Sears increased their credit limit. Sears was the “go to” place for cash strapped consumers. (Eventually, this became what we now call the Discover card.)

In 1930 Sears expanded the Allstate tire line to include selling auto insurance – and consumers could not only maintain their car at Sears they could insure it as well. As its customers grew older and more wealthy, many needed help with financia advice so in 1981 Sears bought Dean Witter and made it possible for customers to figure out a retirement plan while waiting for their tires to be replaced and their car insurance to update.

To put it mildly, Sears was the most innovative retailer of all time. Until the internet came along. Focused on its big stores, and its breadth of products and services, Sears kept trying to sell more stuff through those stores, and to those same customers. Internet retailing seemed insignificantly small, and unappealing. Heck, leadership had discontinued the famous catalogues in 1993 to stop store cannibalization and push people into locations where the company could promote more products and services. Focusing on its core customers shopping in its core retail locations, Sears leadership simply ignored upstarts like Amazon.com and figured its old success formula would last forever.

But they were wrong. The traditional Sears market was niched up across big box retailers like Best Buy, clothiers like Kohls, tool stores like Home Depot, parts retailers like AutoZone, and soft goods stores like Bed, Bath & Beyond. The original need for “one stop shopping” had been overtaken by specialty retailers with wider selection, and often better pricing. And customers now had credit cards that worked in all stores. Meanwhile, for those who wanted to shop for many things from home the internet had taken over where the catalogue once began. Leaving Sears’ market “hollowed out.” While KMart was simply overwhelmed by the vast expansion of WalMart.

What should Lampert have done?

There was no way a cost cutting strategy would save KMart or Sears. All the trends were going against the company. Sears was destined to keep losing customers, and sales, unless it moved onto trends. Lampert needed to innovate. He needed to rapidly adopt the trends. Instead, he kept cutting costs. But revenues fell even faster, and the result was huge paper losses and an outpouring of cash.

To gain more insight, take a look at Jeff Bezos. But rather than harp on Amazon.com’s growth, look instead at the leadership he has provided to The Washington Post since acquiring it just over 2 years ago. Mr. Bezos did not try to be a better newspaper operator. He didn’t involve himself in editorial decisions. Nor did he focus on how to drive more subscriptions, or sell more advertising to traditional customers. None of those initiatives had helped any newspaper the last decade, and they wouldn’t help The Washington Post to become a more relevant, viable and profitable company. Newspapers are a dying business, and Bezos could not change that fact.

Mr. Bezos focused on trends, and what was needed to make The Washington Post grow. Media is under change, and that change is being created by technology. Streaming content, live content, user generated content, 24×7 content posting (vs. deadlines,) user response tracking, readers interactivity, social media connectivity, mobile access and mobile content — these are the trends impacting media today. So that was where he had leadership focus. The Washington Post had to transition from a “newspaper” company to a “media and technology company.”

So Mr. Bezos pushed for hiring more engineers – a lot more engineers – to build apps and tools for readers to interact with the company. And the use of modern media tools like headline testing. As a result, in October, 2015 The Washington Post had more unique web visitors than the vaunted New York Times. And its lead is growing. And while other newspapers are cutting staff, or going out of business, the Post is adding writers, editors and engineers. In a declining newspaper market The Washington Post is growing because it is using trends to transform itself into a company readers (and advertisers) value.

CEO Lampert could have chosen to transform Sears Holdings. But he did not. He became a very, very active “hands on” manager. He micro-managed costs, with no sense of important trends in retail. He kept trying to take cash out, when he needed to invest in transformation. He should have sold the real estate very early, sensing that retail was moving on-line. He should have sold outdated brands under intense competitive pressure, such as Kenmore, to a segment supplier like Best Buy. He then should have invested that money in technology. Sears should have been a leader in shopping apps, supplier storefronts, and direct-to-customer distribution. Focused entirely on defending Sears’ core, Lampert missed the market shift and destroyed all the value which initially existed in the great retail merger he created.

Impact?

Every company must understand critical trends, and how they will apply to their business. Nobody can hope to succeed by just protecting the core business, as it can be made obsolete very, very quickly. And nobody can hope to change a trend. It is more important than ever that organizations spend far less time focused on what they did, and spend a lot more time thinking about what they need to do next. Planning needs to shift from deep numerical analysis of the past, and a lot more in-depth discussion about technology trends and how they will impact their business in the next 1, 3 and 5 years.

Sears Holdings was a 13 year ride. Investor hope that Lampert could cut costs enough to make Sears and KMart profitable again drove the stock very high. But the reality that this strategy was impossible finally drove the value lower than when the journey started. The debacle has ruined 2 companies, thousands of employees’ careers, many shopping mall operators, many suppliers, many communities, and since 2007 thousands of investor’s gains. Four years up, then 9 years down. It happened a lot faster than anyone would have imagined in 2003 or 2004. But it did.

And it could happen to you. Invert your strategic planning time. Spend 80% on trends and scenario planning, and 20% on historical analysis. It might save your business.

by Adam Hartung | Aug 27, 2015 | In the Rapids, Innovation, Investing, Leadership, Web/Tech

As market volatility reached new highs this week, CNBC began talking about something called “FANG Investing.” Most commentators showed great displeasure in the fact that prior to the recent downturn high growth companies such as Facebook, Amazon, Netflix and Google (FANG) had performed much better than all the major market indices. And, in the short burst of recent recovery these companies again seemed to be doing much better.

Coined by “CNBC Mad Money” host Jim Cramer, he felt that FANG investing was bad for investors. He said he preferred seeing a much larger group of companies would go up in value, thus representing a much more stable marketplace.

Coined by “CNBC Mad Money” host Jim Cramer, he felt that FANG investing was bad for investors. He said he preferred seeing a much larger group of companies would go up in value, thus representing a much more stable marketplace.

Sound like Wall Street gobblygook? Good. Because as an individual investor why should you care about a stable market? What you should care about is your individual investments going up in value. And if yours go up and all others go down what difference does it make?

Most financial advisers today actually confuse investors much more than help them. And nowhere is this more true than when discussing risk. All financial advisers (brokers in the old days) ask how much risk you want as an investor. If you’re smart you say “none.” Why would you want any risk? You want to make money.

Only this is the wrong answer, because most investors don’t understand the question – because the financial adviser’s definition of risk is nothing like yours.

To a broker investment risk is this bizarre term called “beta,” created by economists. They defined risk as the degree to which a stock does not move with the market index. If the S&P down 5%, and the stock goes down 5%, then they see no difference between the stock and the “market” so they say it has no risk. If the S&P goes up 3% and the stock goes up 3%, again, no risk.

But if a stock trades based on its own investor expectation, and does not track the market index, then it is considered “high beta” and your broker will say it is “high risk.” So let’s look at Apple the last 5 years. If you had put all your money into Apple 5 years ago you would be up over 200% – over 4x. Had you bought the S&P 500 Index you would be up 80%. Clearly, investing in Apple would have been better. But your adviser would say that is “high risk.” Why? Because Apple did not move with the S&P. It did much better. It is therefore considered high beta, and high risk.

You buy that?

Thus, brokers keep advising investors buy funds of various kinds. Because the investors says she wants low risk, they try to make sure her returns mirror the indices. But it begs the question, why don’t you just buy an electronic traded fund (ETF) that mirrors the S&P or Dow, and quit paying those fund fees and broker fees? If their approach is designed to have you do no better than the average, why not stop the fees and invest in those things which will exactly give you the average?

Anyway, what individual investors want is high returns. And that has nothing to do with market indices or how a stock moves compares to an index. It has to do with growth.

Growth is a wonderful thing. When a company grows it can write off big mistakes and nobody cares. It can overpay employees, give them free massages and lunches, and nobody cares. It can trade some of its stock for a tiny company, implying that company is worth a vast amount, in order to obtain new products it can push to its customers, and nobody cares. Growth hides a multitude of sins, and provides investors with the opportunity for higher valuations.

On the other hand, nobody ever cost cut a company into prosperity. Layoffs, killing products, shutting down businesses and selling assets does not create revenue growth. It causes the company to shrink, and the valuation to decline.

That’s why it is lower risk to invest in FANG stocks than those so-called low-risk portfolios. Companies like Facebook, Amazon, Netflix, Google — and Apple, EMC, Ultimate Software, Tesla and Qualcomm just to name a few others — are growing. They are firmly tied to technologies and products that are meeting emerging needs, and they know their customers. They are doing things that increase long-term value.

McDonald’s was a big winner for investors in the 1960s and 1970s as fast food exploded with the baby boomer generation. But as the market shifted McDonald’s sold off its investments in trend-linked brands Boston Market and Chipotle. Now its revenue has stalled, and its value is in decline as it shuts stores and lays off employees.

Thirty years ago GE tied its plans to trends in medical technology, financial services and media, and it grew tremendously making fortunes for its investors. In the last decade it has made massive layoffs, shut down businesses and sold off its appliance, financial services and media businesses. It is now smaller, and its valuation is smaller.

Caterpillar tied itself to the massive infrastructure growth in Asia and India, and it grew. But as that growth slowed it did not move into new businesses, so its revenues stalled. Now its value is declining as it lays off employees and shuts down business units.

Risk is tied to the business and its future expectations. Not how a stock moves compared to an index. That’s why investing in high growth companies tied to trends is actually lower risk than buying a basket of stocks — even when that basket is an index like DIA or SPY. Why should you own the low-or no-growth dogs when you don’t have to? How is it lower risk to invest in a struggling McDonald’s, GE or Caterpillar or some basket that contains them than investing in companies demonstrating tremendous revenue growth?

Good fishermen go where the fish are. Literally. Anybody can cast out a line and hope. But good fisherman know where the fish are, and that’s where they invest their bait. As an investor, don’t try to fish the ocean (the index.) Be smart, and put your money where the fish are. Invest in companies that leverage trends, and you’ll lower your risk of investment failure while opening the door to superior returns.

Once upon a time, in a land far away, and barely remembered by young people, Microsoft OWNED the tech marketplace. Individuals and companies purchased PCs preloaded with Microsoft Windows 95, Microsoft Office, Microsoft Internet Explorer and a handful of other tools and trinkets. And as companies built networks they used PC servers loaded with Microsoft products. Computing was a Microsoft solution, beginning to end, for the vast majority of users.

Once upon a time, in a land far away, and barely remembered by young people, Microsoft OWNED the tech marketplace. Individuals and companies purchased PCs preloaded with Microsoft Windows 95, Microsoft Office, Microsoft Internet Explorer and a handful of other tools and trinkets. And as companies built networks they used PC servers loaded with Microsoft products. Computing was a Microsoft solution, beginning to end, for the vast majority of users.