by Adam Hartung | Aug 12, 2016 | Diversity, Innovation, Teamwork, Television

Most of the time “diversity” is a code word for adding women or minorities to an organization. But that is only one way to think about diversity, and it really isn’t the most important. To excel you need diversity in thinking. And far too often, we try to do just the opposite.

“Mythbusters” was a television series that ran 14 seasons across 12 years. The thesis was to test all kinds of things people felt were facts, from historical claims to urban legends, with sound engineering approaches to see if the beliefs were factually accurate – or if they were myths. The show’s ability to bust, or prove, these myths made it a great success.

The show was led by 2 engineers who worked together on the tests and props. Interestingly, these two fellows really didn’t like each other. Despite knowing each other for 20 years, and working side-by-side for 12, they never once ate a meal together alone, or joined in a social outing. And very often they disagreed on many aspects of the show. They often stepped on each others toes, and they butted heads on multiple issues. Here’s their own words:

The show was led by 2 engineers who worked together on the tests and props. Interestingly, these two fellows really didn’t like each other. Despite knowing each other for 20 years, and working side-by-side for 12, they never once ate a meal together alone, or joined in a social outing. And very often they disagreed on many aspects of the show. They often stepped on each others toes, and they butted heads on multiple issues. Here’s their own words:

“We get on each other’s nerves and everything all the time, but whenever that happens, we say so and we deal with it and move on,” he explained. “There are times that we really dislike dealing with each other, but we make it work.”

The pair honestly believed it is their differences which made the show great. They challenged each other continuously to determine how to ask the right questions, and perform the right tests, and interpret the results. It was because they were so different that they were so successful. Individually each was good. But together they were great. It was because they were of different minds that they pushed each other to the highest standards, never had an integrity problem, and achieved remarkable success.

Yet, think about how often we select people for exactly the opposite reason. Think about “knock-out” comments and questions you’ve heard that were used to keep from increasing the diversity:

- I wouldn’t want to eat lunch with that person, so why would I want to work with them?

- We find that people with engineering (or chemical, or fine arts, etc.) backgrounds do well here. Others don’t.

- We like to hire people from state (or Ivy League, etc) colleges because they fit in best

- We always hire for industry knowledge. We don’t want to be a training ground for the basics in how our industry works

- Results are not as important as how they were obtained – we have to be sure this person fits our culture

- Directors on our Board need to be able to get along or the Board cannot be effective

- If you weren’t trained in our industry, how could you be helpful?

- We often find that the best/top graduates are unable to fit into our culture

- We don’t need lots of ideas, or challenges. We need people that can execute our direction

- He gets things done, but he’s too rough around the edges to hire (or promote.) If he leaves he’ll be someone else’s problem.

In 2011 I wrote in Forbes “Why Steve Jobs Couldn’t Find a Job Today.” The column pointed out that hiring practices are designed for the lowest common denominator, not the best person to do a job. Personalities like Steve Jobs would be washed out of almost any hiring evaluation because he was too opinionated, and there would be concerns he would cause too much tension between workers, and be too challenging for his superiors.

Simply put, we are biased to hire people that think like us. It makes us comfortable. Yet, it is a myth that homogeneous groups, or cultures, are the best performing. It is the melding of diverse ways of thinking, and doing, that leads to the best solutions. It is the disagreement, the arguing, the contention, the challenging and the uncomfortableness that leads to better performance. It leads to working better, and smarter, to see if your assumptions, ideas and actions can perform better than your challengers. And it leads to breakthroughs as challenges force us to think differently when solving problems, and thus developing new combinations and approaches that yield superior returns.

What should we do to hire better, and develop better talent that produces superior results?

- Put results and accomplishments ahead of culture or fit. Those who succeed usually keep succeeding, and we need to build on those skills for everyone to learn how to perform better

- Don’t let ego into decisions or discussions. Too many bad decisions are made because someone finds their assumptions or beliefs challenged, and thus they let “hurt feelings” keep them from listening and considering alternatives.

- Set goals, not process. Tell someone what they need to accomplish, and not how they should do it. If how someone accomplishes their goals offends you, think about your own assumptions rather than attacking the other person. There can be no creativity if the process is controlled.

- Set big goals, and avoid the desire to set a lot of small goals. When you break down the big goal into sub-goals you effectively kill alternative approaches – approaches that might not apply to these sub-goals. In other words, make sure the big objective is front and center, then “don’t sweat the small stuff.”

- Reward people for thinking differently – and be very careful to not punish them. It is easy to scoff at an idea that sounds foreign, and in doing so kill new ideas. Often it’s not what they don’t know that is material, but rather what you don’t know that is most important.

- Be blind to gender, skin color, historical ancestry, religion and all other elements of background. Don’t favor any background, nor disfavor another. This doesn’t mean white men are the only ones who need to be aware. It is extremely easy for what we may call any minority to favor that minority. Assumptions linked to physical attributes and history run deep, and are hard to remove from our bias. But it is not these historical physical and educational elements that matter, it is how people think that matters – and the results they achieve.

by Adam Hartung | Jun 9, 2016 | Innovation, Investing, Software, Teamwork

Last week Bloomberg broke a story about how Microsoft’s Chairman, John Thompson, was pushing company management for a faster transition to cloud products and services. He even recommended changes in spending might be in order.

Really? This is news?

Let’s see, how long has the move to mobile been around? It’s over a decade since Blackberry’s started the conversion to mobile. It was 10 years ago Amazon launched AWS. Heck, end of this month it will be 9 years since the iPhone was released – and CEO Steve Ballmer infamously laughed it would be a failure (due to lacking a keyboard.) It’s now been 2 years since Microsoft closed the Nokia acquisition, and just about a year since admitting failure on that one and writing off $7.5B And having failed to achieve even 3% market share with Windows phones, not a single analyst expects Microsoft to be a market player going forward.

So just now, after all this time, the Board is waking up to the need to change the resource allocation? That does seem a bit like looking into barn lock acquisition long after the horses are gone, doesn’t it?

The problem is that historically Boards receive almost all their information from management. Meetings are tightly scheduled affairs, and there isn’t a lot of time set aside for brainstorming new ideas. Or even for arguing with management assumptions. The work of governance has a lot of procedures related to compliance reporting, compensation, financial filings, senior executive hiring and firing – there’s a lot of rote stuff. And in many cases, surprisingly to many non-Directors, the company’s strategy may only be a topic once a year. And that is usually the result of a year long management controlled planning process, where results are reviewed and few challenges are expected. Board reviews of resource allocation are at the very, very tail end of management’s process, and commitments have often already been made – making it very, very hard for the Board to change anything.

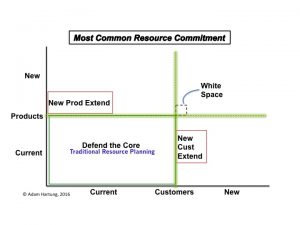

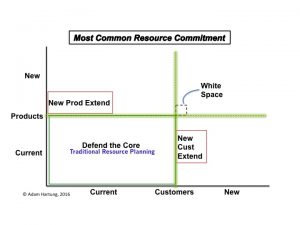

And these planning processes are backward-oriented tools, designed to defend and extend existing products and services, not predict changes in markets. These processes originated out of financial planning, which used almost exclusively historical accounting information. In later years these programs were expanded via ERP (Enterprise Resource Planning) systems (such as SAP and Oracle) to include other information from sales, logistics, manufacturing and procurement. But, again, these numbers are almost wholly historical data. Because all the data is historical, the process is fixated on projecting, and thus defending, the old core of historical products sold to historical customers.

Copyright Adam Hartung

Efforts to enhance the process by including extensions to new products or new customers are very, very difficult to implement. The “owners” of the planning processes are inherent skeptics, inclined to base all forecasts on past performance. They have little interest in unproven ideas. Trying to plan for products not yet sold, or for sales to customers not yet in the fold, is considered far dicier – and therefore not worthy of planning. Those extensions are considered speculation – unable to be forecasted with any precision – and therefore completely ignored or deeply discounted.

And the more they are discounted, the less likely they receive any resource funding. If you can’t plan on it, you can’t forecast it, and therefore, you can’t really fund it. And heaven help some employee has a really novel idea for a new product sold to entirely new customers. This is so “white space” oriented that it is completely outside the system, and impossible to build into any future model for revenue, cost or – therefore – investing.

Take for example Microsoft’s recent deal to sell a bunch of patent rights to Xiaomi in order to have Xiaomi load Office and Skype on all their phones. It is a classic example of taking known products, and extending them to very nearby customers. Basically, a deal to sell current software to customers in new markets via a 3rd party. Rather than develop these markets on their own, Microsoft is retrenching out of phones and limiting its investments in China in order to have Xiaomi build the markets – and keeping Microsoft in its safe zone of existing products to known customers.

The result is companies consistently over-investment in their “core” business of current products to current customers. There is a wealth of information on those two groups, and the historical info is unassailable. So it is considered good practice, and prudent business, to invest in defending that core. A few small bets on extensions might be OK – but not many. And as a result the company investment portfolio becomes entirely skewed toward defending the old business rather than reaching out for future growth opportunities.

This can be disastrous if the market shifts, collapsing the old core business as customers move to different solutions. Such as, say, customers buying fewer PCs as they shift to mobile devices, and fewer servers as they shift to cloud services. These planning systems have no way to integrate trend analysis, and therefore no way to forecast major market changes – especially negative ones. And they lack any mechanism for planning on big changes to the product or customer portfolio. All future scenarios are based on business as it has been – a continuation of the status quo primarily – rather than honest scenarios based on trends.

How can you avoid falling into this dilemma, and avoiding the Microsoft trap? To break this cycle, reverse the inputs. Rather than basing resource allocation on financial planning and historical performance, resource allocation should be based on trend analysis, scenario planning and forecasts built from the future backward. If more time were spent on these plans, and engaging external experts like Board Directors in discussions about the future, then companies would be less likely to become so overly-invested in outdated products and tired customers. Less likely to “stay at the party too long” before finding another market to develop.

If your planning is future-oriented, rather than historically driven, you are far more likely to identify risks to your base business, and reduce investments earlier. Simultaneously you will identify new opportunities worthy of more resources, thus dramatically improving the balance in your investment portfolio. And you will be far less likely to end up like the Chairman of a huge, formerly market leading company who sounds like he slept through the last decade before recognizing that his company’s resource allocation just might need some change.

The show was led by 2 engineers who worked together on the tests and props. Interestingly, these two fellows really didn’t like each other. Despite knowing each other for 20 years, and working side-by-side for 12, they never once ate a meal together alone, or joined in a social outing. And very often they disagreed on many aspects of the show. They often stepped on each others toes, and they butted heads on multiple issues. Here’s their own words:

The show was led by 2 engineers who worked together on the tests and props. Interestingly, these two fellows really didn’t like each other. Despite knowing each other for 20 years, and working side-by-side for 12, they never once ate a meal together alone, or joined in a social outing. And very often they disagreed on many aspects of the show. They often stepped on each others toes, and they butted heads on multiple issues. Here’s their own words: