by Adam Hartung | Apr 25, 2018 | Entertainment, Film, Innovation, Investing, Retail

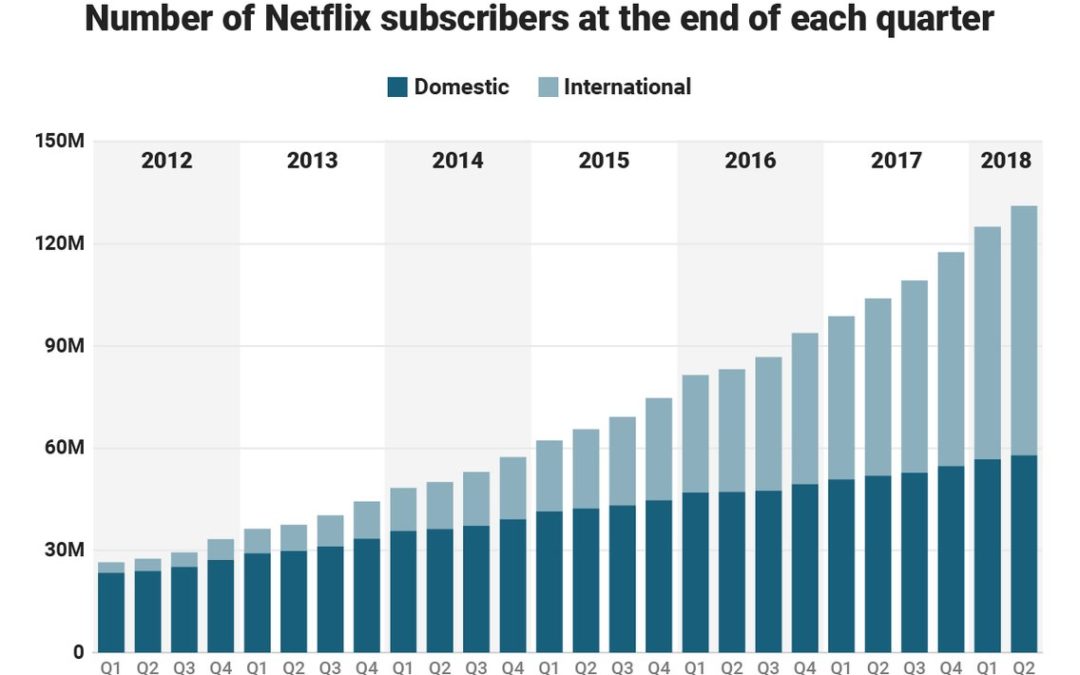

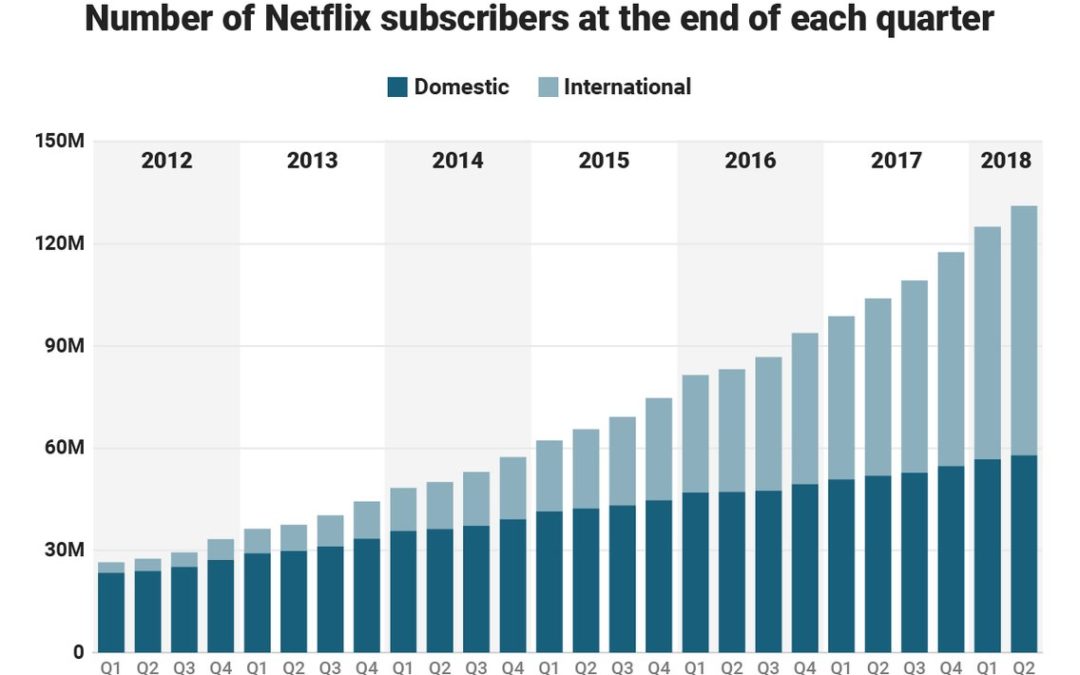

Netflix announced new subscriber numbers last week – and it exceeded expectations. Netflix now has over 130 million worldwide subscribers. This is up 480% in just the last 6 years – from under 30 million. Yes, the USA has grown substantially, more than doubling during this timeframe. But international growth has been spectacular, growing from almost nothing to 57% of total revenues. International growth the last year was 70%, and the contribution margin on international revenues has transitioned from negative in 2016 to over 15% – double the 4th quarter of 2017.

Accomplishing this is a remarkable story. Most companies grow by doing more of the same. Think of Walmart that kept adding stores. Then adding spin-off store brand Sam’s Club. Then adding groceries to the stores. Walmart never changed its strategy, leaders just did “more” with the old strategy. That’s how most people grow, by figuring out ways to make the Value Delivery System (in their case retail stores, warehouses and trucks) do more, better, faster, cheaper. Walmart never changed its strategy.

But Netflix is a very different story. The company started out distributing VHS tapes, and later DVDs, to homes via USPS, UPS and Fedex. It was competing with Blockbuster, Hollywood Video, Family Video and other traditional video stores. It won that battle, driving all of them to bankruptcy. But then to grow more Netflix invested far outside its “core” distribution skills and pioneered video streaming, competing with companies like DirecTV and Comcast. Eventually Netflix leaders raised prices on physical video distribution, cannibalizing that business, to raise money for investing in streaming technology. Streaming technology, however, was not enough to keep growing subscribers. Netflix leadership turned to creating its own content, competing with moviemakers, television and documentary producers, and broadcast television. The company now spends over $6B annually on content.

Think about those decisions. Netflix “pivoted” its strategy 3 times in one decade. Its “core” skill for growth changed from physical product distribution to network technology to content creation. From a “skills” perspective none of these have anything in common.

Could you do that? Would you do that?

How did Netflix do that? By focusing on its Value Proposition. By realizing that it’s Value Proposition was “delivering entertainment” Netflix realized it had to change its skill set 3 times to compete with market shifts. Had Netflix not done so, its physical distribution would have declined due to the emergence of Amazon.com, and eventually disappeared along with tapes and DVDs. Netflix would have followed Blockbuster into history. And as bandwidth expanded, and global networks grew, and dozens of providers emerged streaming purchased content profits would have become a bloodbath. Broadcasters who had vast libraries of content would sell to the cheapest streaming company, stripping Netflix of its growth. To continue growing, Netflix had to look at where markets were headed and redirect the company’s investments into its own content.

This is not how most companies do strategy. Most try to figure out one thing they are good at, then optimize it. They examine their Value Delivery System, focus all their attention on it, and entirely lose track of their Value Proposition. They keep optimizing the old Value Delivery System long after the market has shifted. For example, Walmart was the “low cost retailer.” But e-commerce allows competitors like Amazon.com to compete without stores, without advertising and frequently without inventory (using digital storefronts to other people’s inventory.) Walmart leaders were so focused on optimizing the Value Delivery System, and denying the potential impact of e-commerce, that they did not see how a different Value Delivery System could better fulfill the initial Walmart Value Proposition of “low cost.” The Walmart strategy never took a pivot – and now they are far, far behind the leader, and rapidly becoming obsolete.

Do you know your Value Proposition? Is it clear – written on the wall somewhere? Or long ago did you stop thinking about your Value Proposition in order to focus your intention on optimizing your Value Delivery System?

That fundamental strategy flaw is killing companies right and left – Radio Shack, Toys-R-Us and dozens of other retailers. Who needs maps when you have smartphone navigation? Smartphones put an end to Rand McNally. Who needs an expensive watch when your phone has time and so much more? Apple Watch sales in 2017 exceeded the entire Swiss watch industry. Who needs CDs when you can stream music? Sony sales and profits were gutted when iPods and iPhones changed the personal entertainment industry. (Anyone remember “boom boxes” and “Walkman”?)

I’ve been a huge fan of Netflix. In 2010, I predicted it was the next Apple or Google. When the company shifted strategy from delivering physical entertainment to streaming in 2011, and the stock tanked, I made the case for buying the stock. In 2015 when the company let investors know it was dumping billions into programming I again said it was strategically right, and recommended Netflix as a good investment. And I redoubled my praise for leadership when the “double pivot” to programming was picking up steam in 2016. You don’t have to be mystical to recognize a winner like Netflix, you just have to realize the company is using its strategy to deliver on its Value Proposition, and is willing to change its Value Delivery System because “core strength” isn’t important when its time to change in order to meet new market needs.

by Adam Hartung | Dec 22, 2017 | Advertising, Film, Innovation, Marketing, Trends

Here in late 2017, the biggest trends are: the 24 hour news cycle, animosity in broadcast and online media, fatigue from constant connection and interaction, international threats and our political climate. The holiday season is in the background struggling for attention.

How are people tuning out of this cacophony to get in the mood for the holidays?

The answer: Christmas movies! And which channel has 75% share of the new movies in 2017? If you have watched any TV since October, you’d know that it’s The Hallmark Channel. THC has produced over 20 original movies for the 2017 Christmas season and has seen viewership grow by 6.7% per year since 2013. THC is on track to surpass the 2016 season in viewership and its brand image is solidly wholesome.

Starting in October, THC runs seasonal programming with its successful “The Good Witch” series (no vampires!) and continues with “Countdown to Christmas” featuring original Hallmark-produced content.

Hallmark spent decades preparing to capture the benefits of these trends. It had become a source of family oriented, holiday-themed programming especially popular in recent years. Once only an ink and paper company, Hallmark expanded strategically in the 1970s with ornaments and cultural greeting cards and again in 1984 with its acquisition of Crayola drawing products. The company moved into direct retail in 1986 and ecommerce in the mid-1990s. Hallmark eCards was launched in 2005.

Hallmark capitalized on branded media content originally to support the core business and it now generates profits as a standalone business. In 2001, the Hallmark Channel was launched. The Hallmark Movie Channel was developed in 2004 which became Hallmark Movies and Mysteries in 2014. This year, the Hallmark Drama channel was launched further leveraging the brand.

Many companies sponsored radio shows in the 1920s through the war years. Serials featuring one company’s products appeared in 1928 on radio. In 1952, Proctor and Gamble sponsored the first TV soap opera featuring one company (“The Guiding Light”). But The Hallmark Hall of Fame was there first on Christmas Eve in 1951 sponsoring a made-for-TV opera, “Amahl and the Night Visitors.”

Written by Gian Carlo Menotti in less than two months and timed for a one hour TV slot, “Amahl” has become, probably, the most performed opera in history.

Hallmark wasn’t the first mover in sponsored media content, but it had learned to experiment with new media. The company was positioned to take advantage of the trend toward family friendly broadcast content and this year was ready to give the nation a place to rest and escape from the chaos. A bit like the story of Amahl and Christmas itself.

Once just a card company, Hallmark followed market trends to expand its business and become a leader in content marketing which is now one of the hottest areas in all marketing. And both the new video content and large library were ready for the current trend- streaming video!

by Adam Hartung | Oct 4, 2011 | Current Affairs, Defend & Extend, Film, In the Rapids, Innovation, Leadership, Television, Transparency, Web/Tech

Reed Hastings, the CEO of Netflix, has long been considered a pretty good CEO. In January, 2009 his approval ranking, from Glassdoor, was an astounding 93%. In January, 2010 he was still on the top 25 list, with a 75% approval rating. And it's not surprising, given that he had happy employees, happy customers, and with Netflix's successful trashing of Blockbuster the company's stock had risen dramaticall,y leading to very happy investors.

But that was before Mr. Hastings made a series of changes in July and September. First Netflix raised the price on DVD rentals, and on packages that had DVD rentals and streaming download, by about $$6/month. Not a big increase in dollar terms, but it was a 60% jump, and it caught a lot of media attention (New York Times article). Many customers were seriously upset, and in September Netflix let investors know it had lost about 4% of its streaming subscribers, and possibly as many as 5% of its DVD subscribers (Daily Mail).

No investor wants that kind of customer news from a growth company, and the stock price went into a nosedive. The decline was augmented when the CEO announced Netflix was splitting into 2 companies. Netflix would focus on streaming video, and Quikster would focus on DVDs. Nobody understood the price changes – or why the company split – and investors quickly concluded Netflix was a company out of control and likely to flame out, ruined by its own tactics in competition with Amazon, et.al.

(Source: Yahoo Finance 3 October, 2011)

(Source: Yahoo Finance 3 October, 2011)

This has to be about the worst company communication disaster by a market leader in a very, very long time. TVWeek.com said Netflix, and Reed Hastings, exhibited the most self-destructive behavior in 2011 – beyond even the Charlie Sheen fiasco! With everything going its way, why, oh why, did the company raise prices and split? Not even the vaunted New York Times could figure it out.

But let's take a moment to compare Netflix with another company having recent valuation troubles – Kodak.

Kodak invented home photography, leading it to tremendous wealth as amature film sales soared for seveal decades. But last week Kodak announced it was about out of cash, and was reaching into its revolving credit line for some $160million to pay bills. This latest financial machination reinforced to investors that film sales aren't what they used to be, and Kodak is in big trouble – possibly facing bankruptcy. Kodak's stock is down some 80% this year, from $6 to $1 – and quite a decline from the near $80 price it had in the late 1990s.

(Source: Yahoo Finance 10-3-2011)

Why Kodak declined was well described in Forbes. Despite its cash flow and company strengths, Kodak never succeeded beyond its original camera film business. Heck, Kodak invented digital photography, but licensed the technology to others as it rabidly pursued defending film sales. Because Kodak couldn't adapt to the market shift, it now is probably going to fail.

And that is why it is worth revisiting Netflix. Although things were poorly explained, and certainly customers were not handled well, last quarter's events are the right move for investors in the shifting at-home video entertainment business:

- DVD sales are going the direction of CD's and audio cassettes. Meaning down. It is important Netflix reap the maximum value out of its strong DVD position in order to fund growth in new markets. For the market leader to raise prices in low growth markets in order to maximize value is a classic strategic step. Netflix should be lauded for taking action to maximize value, rather than trying to defend and extend a business that will most likely disappear faster than any of us anticipate – especially as smart TVs come along.

- It is in Netflix's best interest to promote customer transition to streaming. Netflix is the current leader in streaming, and the profits are better there. Raising DVD prices helps promote customer shifting to the new technology, and is good for Netflix as long as customers don't change to a competitor.

- Although Netflix is currently the leader in streaming it has serious competition from Hulu, Amazon, Apple and others. It needs to build up its customer base rapidly, before people go to competitors, and it needs to fund its streaming business in order to obtain more content. Not only to negotiate with more movie and TV suppliers, but to keep funding its exclusive content like the new Lillyhammer series (more at GigaOm.com). Content is critical to maintaining leadership, and that requires both customers and cash.

- Netflix cannot afford to muddy up its streaming strategy by trying to defend, and protect, its DVD business. Splitting the two businesses allows leaders of each to undertake strategies to maximize sales and profits. Quikster will be able to fight Wal-Mart and Redbox as hard as possible, and Netflix can focus attention on growing streaming. Again, this is a great strategic move to make sure Netflix transitions from its old DVD business into streaming, and doesn't end up like an accelerated Kodak story.

Historically, companies that don't shift with markets end up in big trouble. AB Dick and Multigraphics owned small offset printing, but were crushed when Xerox brought out xerography. Then, afater inventing desktop publishing at Xerox PARC, Xerox was crushed by the market shift from copiers to desktop printers – a shift Xerox created. Pan Am, now receiving attention due to the much hyped TV series launch, failed when it could not make the shift to deregulation. Digital Equipment could not make the shift to PCs. Kodak missed the shift from film to digital. Most failed companies are the result of management's inability to transition with a market shift. Trying to defend and extend the old marketplace is guaranteed to fail.

Today markets shift incredibly fast. The actions at Netflix were explained poorly, and perhaps taken so fast and early that leadership's intentions were hard for anyone to understand. The resulting market cap decline is an unmitigated disaster, and the CEO should be ashamed of his performance. Yet, the actions taken were necessary – and probably the smartest moves Netflix could take to position itself for long-term success.

Perhaps Netflix will fall further. Short-term price predictions are a suckers game. But for long-term investors, now that the value has cratered, give Netflix strong consideration. It is still the leader in DVD and streaming. It has an enormous customer base, and looks like the exodus has stopped. It is now well organized to compete effectively, and seek maximum future growth and value. With a better PR firm, good advertising and ongoing content enhancements Netflix has the opportunity to pull out of this communication nightmare and produce stellar returns.

by Adam Hartung | Sep 22, 2010 | Current Affairs, Defend & Extend, Film, In the Whirlpool, Leadership, Lifecycle, Lock-in, Music, Web/Tech

Summary:

- Video retailer Blockbuster (and competitor Hollywood Video) are now bankrupt

- Video rentals/sales are at an all time high – but via digital downloads not DVDs

- Nokia, once the cell phone industry leader, is in deep trouble and risk of failure

- Yet mobile use (calls, texts, internet access, email) is at an all time high

- These companies are victims of locking-in to old business models, and missing a market shift

- Commitment to defending your old business can cause failure, even when participating in high growth markets, if you don’t anticipate, embrace and participate in market shifts

- Lock-in is deadly. It can cause you to ignore a market shift.

According to YahooNews, “Blockbuster Video to File Chapter 11.” In February, Movie Gallery – the owner of primary in-kind competitor Hollywood Video – filed for bankruptcy. It’s now decided to liquidate.

The cause is market shift. Netflix made it possible to rent DVDs without the cost of a store – as has the kiosk competitor Red Box. But everyone knows that is just a stopgap, because Netflix and Hulu are leading us all toward a future where there is no physical product at all. We’ll download the things we want to watch. The market is shifting from physical items – video cassettes then DVDs – to downloads. And both Blockbuster and Hollywood Video missed the shift.

Blockbuster (or Hollywood) could have gotten into on-line renting, or kiosks, like its competition. It even could have used profits to be an early developer of downloadable movies. Nothing stopped Blockbuster from investing in YouTube. Except it’s commitment to its Success Formula – as a brick-and-mortar retailer that rented or sold physically reproduced entertainment. Lock-in. And for that commitment to its historical Success Formula the investors now will get a great big goose egg – and employees will get to be laid off – and the thousands of landlords will be left in the lurch, unprepared.

As predictable as Blockbuster was, we can be equally sure about the future of former powerhouse Nokia. Details are provided in the BusinessWeek.com article “How Nokia Fell from Grace.” As the cell phone business exploded in the 1990s Nokia was a big winner. Revenues grew fivefold between 1996 and 2001 as people around the globe gobbled up the new devices. Another example of the fact that when you enter a high growth market you don’t have to be good – just in the right market at the right time.

But the cell phone business has become the mobile device business. And Nokia didn’t anticipate, prepare for or participate in the market shift. From market dominance, it has become an also-ran. The article author blames the failure, and decline, on complacent management. Weak explanation. You can be sure the leadership and management at Nokia was doing all it possibly could to Defend & Extend its cell phone business. The problem is that D&E management doesn’t work when customers simply walk away to a new technology. It may take a few years, and government subsidies may extend Nokia’s life even longer, but Nokia has about as much chance of surviving its market shift as Blockbuster did.

When companies stumble management sees the problems. They know results are faltering. But for decades management has been trained to think that the proper response is to “knuckle down, cut costs, defend the current business at all cost.” Yet, there are more movies rented now than ever – and Blockbuster is failing despite enormous market growth. There are more mobile telephony minutes, text messages, remote emails and mobile internet searches than ever in history – yet Nokia is doing remarkably poorly. It’s not a market problem, it’s a problem of Lock-in to a solution that is now outdated. When the old supplier didn’t give the market what it wanted, the customers went elsewhere. And unwillingness to go with them has left these companies in tatters.

These markets are growing, yet the purveyors of old solutions are failing primarily because they stuck to defending their old business too long. They did not embrace the market shift, and cannibalize historical product sales to enter the new, higher growth markets. Because they chose to protect their “core,” they failed. New victims of Lock-in.

by Adam Hartung | Mar 24, 2010 | Current Affairs, Defend & Extend, Disruptions, Film, In the Whirlpool, Leadership, Lock-in

Blockbuster Video is in big trouble. Most analysts think the company is going to file bankruptcy – unlikely to survive – with a mere $.30 stock price today. Most of us remember when the weekly (or more frequent) trip to Blockbuster was part of every day life. Like too many companies, Blockbuster was in the Rapids of growth when people wanted VHS tapes, then DVDs, to rent – and CDs to purchase. We happily paid up several dollars for rentals and purchases. Blockbuster grew quickly, and developed a powerful Success Formula that aided its growth.

As it is failing, I was startled by a Forbes.com article "What Blockbuster Video Can Teach Us About Economics." The author contends that this failure is a good thing, because it will release poorly used resources to new application. Like most economists, his idea has good theory. But I doubt the employees (who lose pay and benefits), shareholders, debt holders, bankers, landlords and suppliers – as well as the remaining customers, appreciate his point of view. Theory won't help them deal with lost cash flow and expensive transition costs.

As the market shifted to mail order and on-line downloads, Blockbuster could have changed its Success Formula. But instead the company remained Locked-in to doing what it has always done. It will fail not because some force of nature willed its demise. Rather, management made the bad decision to try Defending & Extending an out of date business model – rather than exploring market shifts, studying the competition intensely then using Disruptions and White Space to attack both Netflix and the on-line players. Blockbuster's demise was not a given. Rather, it was a result of following out of date management practices that now have serious costs to the businesses and people who are part of the Blockbuster eco-system. I struggle to see how that is a good thing.

Fortunately, ManagementExcellence.com has a great article about ideas for attacking a threatened Success Formula in order to avoid becoming a Blockbuster entitled "Leadership Caffeine: 7 Odd Ideas to Help You Get Unstuck." The author specifically takes aim at the comfort of Lock-in, and describes how managers can start to make Disruption part of everyday life:

- Fight the tyranny of Recurring Meetings

- Rotate Leadership

- Break the back of bad-habit brainstorming

- Do something completely off-task with your group

- Introduce your team to thought leaders and innovators

- Play games

- Change up your routine

Described in detail in the article, these are simple things anybody can do that begin to reveal how deeply we Lock-in, and expose the power of how we could behave differently. If Blockbuster management had applied these ideas, the company would have been a lot more likely to return positively to society – rather than become another bankruptcy statistic.

by Adam Hartung | Apr 20, 2009 | Current Affairs, Defend & Extend, Film, General, In the Swamp, Leadership, Lock-in, Television

How do you pick a movie to see – whether at the theatre or at home? The movie studios think you pick movies by what you see on TV ads, according to the Los Angeles Times "Studios struggle to rein in marketing costs."

I remember the old days when my friends and I grabbed a newspaper and shopped the ads looking for a flick to go see. And we were influenced by television ads as well. But, as time went by, we started asking each other, "Is that movie any good, or are all the best parts in the ad?" (Admit it, you've asked that question too.) Then we found out we could get sneak peaks from shows like "Siskel & Ebert at the movies," so one of us would try to watch that and see if we liked the longer scenes. And we didn't ever agree with the critics, but we could listen to hear if they described a movie we would like. Now, not only myself but my sons follow the same routine. Only we go to the internet looking for a YouTube! clip, and for reviews from all kinds of people – not just critics. Mostly when we see a TV ad we hit the mute button.

Everywhere, businesses are still wasting money on old business notions. For movie studios, they keep trying to get people to watch a big budget by advertising the thing. (To death. Until nobody watches the ad any more because they have it memorized. And get angry that the ad keeps showing.) But even the above article admits that studios know this isn't the best way any more. With the internet around, we all listen less to advertisements, and gain access to more real input. From web sites, or Twitter, or friends on Facebook, or colleagues on Linked-in. We watch a lot less TV, and what we watch is more targeted to our interest and available on cable. Or we download our TV from the web using Hulu.com. Yet, the studios are so Locked-in to their outdated Success Formula that they keep spending money on TV ads – even though they know the value isn't there any more.

So why do the studios spend so much on advertising? Because they always have. That's Lock-in. Lacking a better idea, a better plan, a better approach that would really reach out to potential viewers they keep doing what they know how to do, even as they question whether or not they should do it! The industrial era concept was "I spent a fortune making this movie, and distributing it into theatres, so I better not stop now. Keep spending money to advertise it, create awareness, and get people into the theatres." The studios see movie making as an industrial enterprise, where those who spend the most have the greatest chance of winning. Spend a lot to make, spend to distribute, spend to advertise. To industrial era thinkers, all this spending creates entry barriers that defends their business.

And that's why movie studios struggle. It's unclear how well those ideas ever worked for filmmaking – because we all saw our share of blockbuster bombs and remember the "American Graffiti" or "Blair Witch Project" that was cheap and good. But for sure we all know the world has now permanently shifted. Today, small budget movies like "Slum Dog Millionaire" can be made (offshore in that case – but not necessarily) quite well. The pool of new actors, writers, directors, cinematographers and editors keeps growing – driving production quality up and cost down. And distribution can be via DVD – or web download – between low cost and free. A movie doesn't even have to be shown in a theatre for it to be commercially successful any more. And any filmmaker can promote her product on the internet, building a word of mouth driving popularity and sales.

From filmmaking to recordings to short programs to books, the market has shifted. Things don't have to be big budget to be good. The old status quo police, like Mr. Goldwyn or Mr. Meyer, simply have far less role. Digitization and globalization means that you don't need film for movies – or paper for books. Thus, democratizing the production, as well as sales, of "media" products. Thus the old media companies are struggling (publishers, filmmakers, magazines, newspapers and recording studios) because they no longer have the "entry barriers" they can Defend to allow their old Success Formulas to produce above average returns. And they never will again. The world has changed, and the market has permanently shifted.

Is your business still spending money on things that don't matter? Does your approach to the market, your Success Formula dictate spending on advertising, salespeople, PR, external analysts, paid reviewers or others that really don't make nearly as much difference any more? When will you change your approach? The movie studios are preparing to spend hundreds of millions of dollars on summer ad promotions for new movies. Is this necessary, given that the downturn has increased the demand for escapist entertainment? Is your business doing the same?

If you want to cut your cost, you shouldn't cut 5% or 10% across the board. That won't help your Success Formula meet market needs better. Instead, you need to understand market shifts and cut 90% from things that no longer matter – or that have diminishing value. Quit doing the things you do because you always did them, and make sure you do the things you need to do. You want to be the next "Slumdog Millionaire" not the next "Ishtar." You want to be Apple, not Motorola. You want to be Google, not Tribune Corporation. Spend money on what pays off, not what you've always spent it on.