by Adam Hartung | Dec 6, 2015 | Current Affairs, Defend & Extend, In the Whirlpool, Leadership, Web/Tech

Marissa Mayer’s reign as head of Yahoo looks to be ending like her predecessors. With a serious flop. Only this may well be the last flop – and the end of the internet pioneer.

It didn’t have to happen this way, but an inability to manage Status Quo Risk doomed Ms. Mayer’s leadership – as it has too many others. And once again bad leadership will see a lot of people – investors, employees and even customers – pay the price.

Yahoo was in big trouble when Ms. Mayer arrived. Growth had stalled, and its market was being chopped up by Google and Facebook. It’s very relevancy was questionable as people no longer needed news consolidation sites – which had ended AOL, for example – and search had long gone to Google. The intense internet users were already clearly mobile social media fans, and Yahoo simply did not compete in that space.

In other words, Yahoo desperately needed a change of direction and an entirely new strategy the day Ms. Mayer showed up. Only, unfortunately, she didn’t provide either. Instead Ms. Meyer offered, at best, a series of fairly meaningless tactical actions. Changing Yahoo’s home page layout, cancelling the company’s work-from-home policy and hiring Katie Couric, amidst a string of small and meaningless acquisitions, were the business equivalent of fiddling while Rome burned. Tinkering with the tactics of an outdated success formula simply ignored the fact that Yahoo was already well on the road to irrelevancy and needed to change, dramatically, quickly.

The saving grace for Yahoo was when Alibaba went public. Suddenly a long-ago decision to invest in the Chinese company created a vast valuation increase for Yahoo. This was the opportunity of a lifetime to shift the business fast and hard into something new, different and much more relevant than the worn out Yahoo strategy. But, unfortunately, Ms. Mayer used this as a curtain to hide the crumbling former internet leader. She did nothing to make Yahoo relevant, as fights erupted over how to carve up the Alibaba windfall.

When it became public that Ms. Mayer had hired famed strategy firm McKinsey & Co. to decide what businesses to close in its next “restructuring” it lit up the internet with cries to possibly just get rid of the whole thing! After 3 years, and more than one layoff, it now appears that Ms. Mayer has no better idea for creating value out of Yahoo than doing another big layoff to, once again, improve “focus on core offerings.” Additional layoffs, after 3 years of declining sales, is not the way to grow and increase shareholder value.

Analysts are pointing out that Yahoo’s core business today is valueless. The company is valued at less than its remaining Alibaba stake. And this is not outrageous, since in the ad world Yahoo has become close to irrelevant. Nobody would build an on-line ad campaign ignoring Google or Facebook, and several other internet leaders. But ignoring Yahoo as a media option is increasingly common.

Investors are rightly worried that the IRS will take much of the remaining Alibaba value as taxes in any spinoff, leaving them with far less money. Giving up on the CEO, and its increasingly irrelevant “core business” they are asking if it wouldn’t be smarter to sell what we think of as Yahoo to Softbank so the Japanese company can obtain the rest of Yahoo Japan it does not already own. Ostensibly then Yahoo as it is known in the USA could simply start to disappear – like AOL and all the other on-line news consolidators.

It really did not have to happen this way. Yahoo’s troubles were clearly visible, and addressable. But CEO Mayer simply chose to keep doing more of the same, making small improvements to Yahoo’s site and search tool. By keeping Yahoo aligned with its historical Status Quo risk of irrelevance, obsolescence and failure grew quarter-by-quarter.

It really did not have to happen this way. Yahoo’s troubles were clearly visible, and addressable. But CEO Mayer simply chose to keep doing more of the same, making small improvements to Yahoo’s site and search tool. By keeping Yahoo aligned with its historical Status Quo risk of irrelevance, obsolescence and failure grew quarter-by-quarter.

Now Status Quo Risk (the risk created by not adapting to shifting market needs) has most likely doomed Yahoo. Investors are no longer interested in waiting for a turn-around. They want their Alibaba valuation, and they could care less about Yahoo’s CEO, employees or customers. Many have given up on Ms. Mayer, and simply want an exit strategy so they can move on.

Ms. Mayer’s leadership has shown us some important leadership lessons:

- Hiring an executive from Google (or another tech company) does not magically mean success will emerge. Like Ron Johnson from Apple to JCP, Ms. Mayer showed that even tech execs often lack an ability to understand market trends and the skills to adapt an organization.

- It is incredibly easy for a new leader to buy into an historical success formula and keep tweaking it, rather than doing the hard work of creating a new strategy and adapting. The lure of focusing on tactics and hoping the strategy will take care of itself is remarkably easy fall into. But investors need to realize that tactics do not fix an outdated success formula.

- Youth is not the answer. Ms. Mayer was young, and identified with the youthfulness of Google and internet users. But, in the end, she woefully lacked the strategy and leadership skills necessary to turn around the deeply troubled Yahoo. Young, new and fresh is no substitute for critical thinking and knowing how to lead.

- Boards give CEOs too much time to fail. It was clear within months Ms. Mayer had no strategy for making Yahoo relevant. Yet, the Board did not recognize its mistake and replace the CEOs. There still are not sufficient safeguards to make sure Boards act when CEOs fail to lead effectively.

- CEOs too often have too much hubris. Ms. Mayer went from college to a rapid career acceleration in largely staff positions to CEO of Yahoo and a Board member of Wal-Mart. It is easy to develop hubris, and an over-abundance of self-confidence. Then it is easy to require your staff agree with you, and pledge so support you (as Ms. Mayer recently did.) All of this indicates a leader running on hubris rather than critical thinking, open discourse and effective decision-making. Hubris is not just a weakness of white male leaders.

Could there have been a different outcome. Of course. But for Yahoo’s employees, suppliers, customers and investors the company hired a string of CEOs that simply were not up to the job of redirecting the company into competitiveness. Each one fell victim to trying to maintain the Status Quo. And, unfortunately, Ms. Mayer will be seen as the most recent – and possibly last – CEO to lead Yahoo into failure. Ms. Mayer simply was not up to the job – and now a lot of people will pay the price.

by Adam Hartung | Nov 18, 2015 | Current Affairs, Defend & Extend, In the Swamp, In the Whirlpool, Leadership, Web/Tech

Microsoft recently announced it was offering Windows 10 on xBox, thus unifying all its hardware products on a single operating system – PCs, mobile devices, gaming devices and 3D devices. This means that application developers can create solutions that can run on all devices, with extensions that can take advantage of inherent special capabilities of each device. Given the enormous base of PCs and xBox machines, plus sales of mobile devices, this is a great move that expands the Windows 10 platform.

Only it is probably too late to make much difference. PC sales continue falling – quickly. Q3 PC sales were down over 10% versus a year ago. Q2 saw an 11% decline vs year ago. The PC market has been steadily shrinking since 2012. In Q2 there were 68M PCs sold, and 66M iPhones. Hope springs eternal for a PC turnaround – but that would seem increasingly unrealistic.

The big market shift to mobile devices started back in 2007 when the iPhone began challenging Blackberry. By 2010 when the iPad launched, the shift was in full swing. And that’s when Microsoft’s current problems really began. Previous CEO Steve Ballmer went “all-in” on trying to defend and extend the PC platform with Windows 8 which began development in 2010. But by October, 2012 it was clear the design had so many trade-offs that it was destined to be an Edsel-like flop – a compromised product unable to please anyone.

The big market shift to mobile devices started back in 2007 when the iPhone began challenging Blackberry. By 2010 when the iPad launched, the shift was in full swing. And that’s when Microsoft’s current problems really began. Previous CEO Steve Ballmer went “all-in” on trying to defend and extend the PC platform with Windows 8 which began development in 2010. But by October, 2012 it was clear the design had so many trade-offs that it was destined to be an Edsel-like flop – a compromised product unable to please anyone.

By January, 2013 sales results were showing the abysmal failure of Windows 8 to slow the wholesale shift into mobile devices. Ballmer had played “bet the company” on Windows 8 and the returns were not good. It was the failure of Windows 8, and the ill-fated Surface tablet which became a notorious billion dollar write-off, that set the stage for the rapid demise of PCs.

And that demise is clear in the ecosystem. Microsoft has long depended on OEM manufacturers selling PCs as the driver of most sales. But now Lenovo, formerly the #1 PC manufacturer, is losing money – lots of money – putting its future in jeopardy. And Dell, one of the other top 3 manufacturers, recently pivoted from being a PC manufacturer into becoming a supplier of cloud storage by spending $67B to buy EMC. The other big PC manufacturer, HP, spun off its PC business so it could focus on non-PC growth markets.

And, worse, the entire OEM market is collapsing. For the largest 4 PC manufacturers sales last quarter were down 4.5%, while sales for the remaining smaller manufacturers dropped over 20%! With fewer and fewer sales, consolidation is wiping out many companies, and leaving those remaining in margin killing to-the-death competition.

And, worse, the entire OEM market is collapsing. For the largest 4 PC manufacturers sales last quarter were down 4.5%, while sales for the remaining smaller manufacturers dropped over 20%! With fewer and fewer sales, consolidation is wiping out many companies, and leaving those remaining in margin killing to-the-death competition.

Which means for Microsoft to grow it desperately needs Windows 10 to succeed on devices other than PCs. But here Microsoft struggles, because it long eschewed its “channel suppliers,” who create vertical market applications, as it relied on OEM box sales for revenue growth. Microsoft did little to spur app development, and rather wanted its developers to focus on installing standard PC units with minor tweaks to fit vertical needs.

Today Apple and Google have both built very large, profitable developer networks. Thus iOS offers 1.5M apps, and Google offers 1.6M. But Microsoft only has 500K apps largely because it entered the world of mobile too late, and without a commitment to success as it tried to defend and extend the PC. Worse, Microsoft has quietly delayed Project Astoria which was to offer tools for easily porting Android apps into the Windows 10 market.

Microsoft realized it needed more developers all the way back in 2013 when it began offering bonuses of $100,000 and more to developers who would write for Windows. But that had little success as developers were more keen to achieve long-term sales by building apps for all those iOS and Android devices now outselling PCs. Today the situation is only exacerbated.

By summer of 2014 it was clear that leadership in the developer world was clearly not Microsoft. Apple and IBM joined forces to build mobile enterprise apps on iOS, and eventually IBM shifted all its internal PCs from Windows to Macintosh. Lacking a strong installed base of Windows mobile devices, Microsoft was without the cavalry to mount a strong fight for building a developer community.

In January, 2015 Microsoft started its release of Windows 10 – the product to unify all devices in one O/S. But, largely, nobody cared. Windows 10 is lots better than Win8, it has a great virtual assistant called Cortana, and it now links all those Microsoft devices. But it is so incredibly late to market that there is little interest.

Although people keep talking about the huge installed base of PCs as some sort of valuable asset for Microsoft, it is clear that those are unlikely to be replaced by more PCs. And in other devices, Microsoft’s decisions made years ago to put all its investment into Windows 8 are now showing up in complete apathy for Windows 10 – and the new hybrid devices being launched.

AM Multigraphics and ABDick once had printing presses in every company in America, and much of the world. But when Xerox taught people how to “one click” print on a copier, the market for presses began to die. Many people thought the installed base would keep these press companies profitable forever. And it took 30 years for those machines to eventually disappear. But by 2000 both companies went bankrupt and the market disappeared.

Those who focus on Windows 10 and “universal windows apps” are correct in their assessment of product features, functions and benefits. But, it probably doesn’t matter. When Microsoft’s leadership missed the mobile market a decade ago it set the stage for a long-term demise. Now that Apple dominates the platform space with its phones and tablets, followed by a group of manufacturers selling Android devices, developers see that future sales rely on having apps for those products. And Windows 10 is not much more relevant than Blackberry.

by Adam Hartung | Oct 25, 2015 | Current Affairs, Defend & Extend, Food and Drink, In the Swamp, In the Whirlpool, Leadership, Web/Tech

This week McDonald’s and Microsoft both reported earnings that were higher than analysts expected. After these surprise announcements, the equities of both companies had big jumps. But, unfortunately, both companies are in a Growth Stall and unlikely to sustain higher valuations.

McDonald’s profits rose 23%. But revenues were down 5.3%. Leadership touted a higher same store sales number, but that is completely misleading.

McDonald’s leadership has undertaken a back to basics program. This has been used to eliminate menu items and close “underperforming stores.” With fewer stores, loyal customers were forced to eat in nearby stores – something not hard to do given the proliferation of McDonald’s sites. But some customers will go to competitors. By cutting stores and products from the menu McDonald’s may lower cost, but it also lowers the available revenue capacity. This means that stores open a year or longer could increase revenue, even though total revenues are going down.

Profits can go up for a raft of reasons having nothing to do with long-term growth and sustainability. Changing accounting for depreciation, inventory, real estate holdings, revenue recognition, new product launches, product cancellations, marketing investments — the list is endless. Further, charges in a previous quarter (or previous year) could have brought forward costs into an earlier report, making the comparative quarter look worse while making the current quarter look better.

Confusing? That’s why accounting changes are often called “financial machinations.” Lots of moving numbers around, but not necessarily indicating the direction of the business.

McDonald’s asked its “core” customers what they wanted, and based on their responses began offering all-day breakfast. Interpretation – because they can’t attract new customers, McDonald’s wants to obtain more revenue from existing customers by selling them more of an existing product; specifically breakfast items later in the day.

Sounds smart, but in reality McDonald’s is admitting it is not finding new ways to grow its customer base, or sales. The old products weren’t bringing in new customers, and new products weren’t either. As customer counts are declining, leadership is trying to pull more money out of its declining “core.” This can work short-term, but not long-term. Long-term growth requires expanding the sales base with new products and new customers.

Perhaps there is future value in spinning off McDonald’s real estate holdings in a REIT. At best this would be a one-time value improvement for investors, at the cost of another long-term revenue stream. (Sort of like Chicago selling all its future parking meter revenues for a one-time payment to bail out its bankrupt school system.) But if we look at the Sears Holdings REIT spin-off, which ostensibly was going to create enormous value for investors, we can see there were serious limits on the effectiveness of that tactic as well.

MIcrosoft also beat analysts quarterly earnings estimate. But it’s profits were up a mere 2%. And revenues declined 12% versus a year ago – proving its Growth Stall continues as well. Although leadership trumpeted an increase in cloud-based revenue, that was only an 8% improvement and obviously not enough to offset significant weakness in other markets:

It is a struggle to see the good news here. Office 365 revenues were up, but they are cannibalizing traditional Office revenues – and not fast enough to replace customers being lost to competitive products like Google OfficeSuite, etc.

Azure sales were up, but not fast enough to replace declining Windows sales. Further, Azure competes with Amazon AWS, which had remarkable results in the latest quarter. After adding 530 new features, AWS sales increased 15% vs. the previous quarter, and 78% versus the previous year. Margins also increased from 21.4% to 25% over the last year. Azure is in a growth market, but it faces very stiff competition from market leader Amazon.

We build our companies, jobs and lives around successful products and services. We want these providers to succeed because it makes our lives much easier. We don’t like to hear about large market leaders losing their strength, because it signals potentially difficult change. We want these companies to improve, and we will clutch at any sign of improvement.

As investors we behave similarly. We were told large companies have vast customer bases, strong asset bases, well known brands, high switching costs, deep pockets – all things Michael Porter told us in the 1980s created “moats” protecting the business, keeping it protected from market shifts that could hurt sales and profits. As investors we want to believe that even though the giant company may slip, it won’t fall. Time and size is on its side we choose to believe, so we should simply “hang on” and “ride it out.” In the future, the company will do better and value will rise.

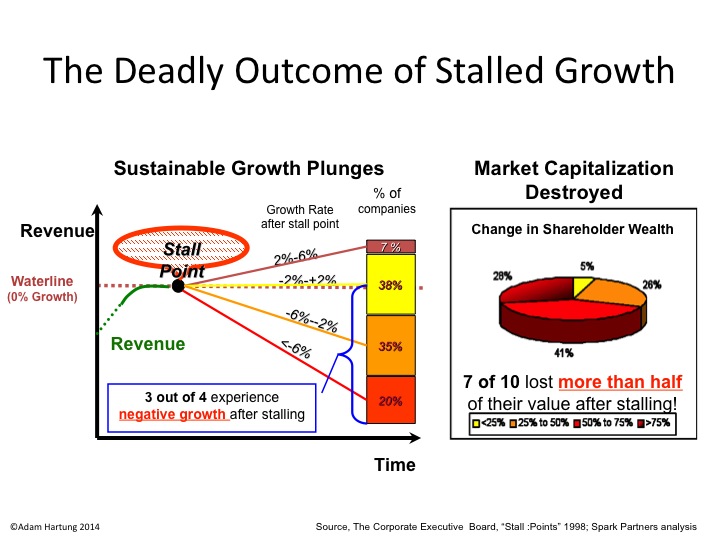

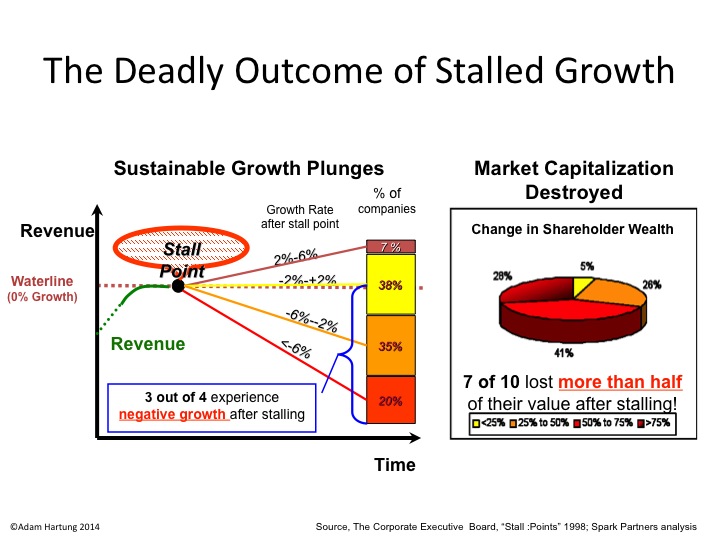

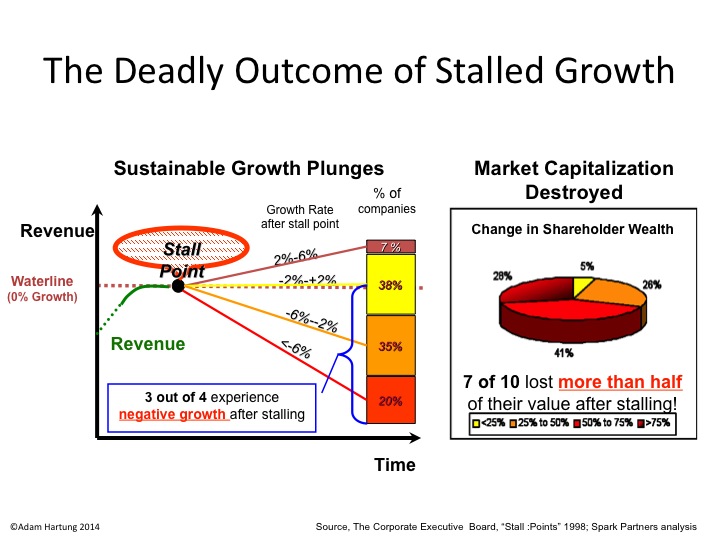

As a result we see that Growth Stall companies show a common valuation pattern. After achieving high valuation, their equity value stagnates. Then, hopes for a turn-around and recovery to new growth is stimulated by a few pieces of good news and the value jumps again. Only after a few years the short-term tactics are used up and the underlying business weakness is fully exposed. Then value crumbles, frequently faster than remaining investors anticipated.

McDonald’s valuation rose from $62/share in 2008 to reach record $100/share highs in 2011. But valuation then stagnated. It is only this last jump that has caused it to reach new highs. But realize, this is on a smaller number of stores, fewer products and declining revenues. These are not factors justifying sustainable value improvement.

Microsoft traded around $25/share from March, 2003 through November, 2011 – 8.5 years. When the CEO was changed value jumped to $48/share by October, 2014. After dipping, now, a year later Microsoft stock is again reaching that previous valuation ($50/share). Microsoft is now valued where it was in December, 2002 (which is half its all-time high.)

The jump in value of McDonald’s and Microsoft happened on short-term news regarding beating analysts earnings expectations for one quarter. The underlying businesses, however, are still suffering declining revenue. They remain in Growth Stalls, and the odds are overwhelming that their values will decline, rather than continue increasing.

by Adam Hartung | Oct 16, 2015 | Current Affairs, Defend & Extend, In the Swamp, Lifecycle

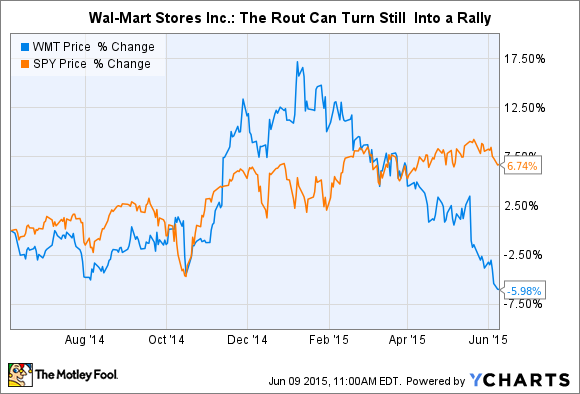

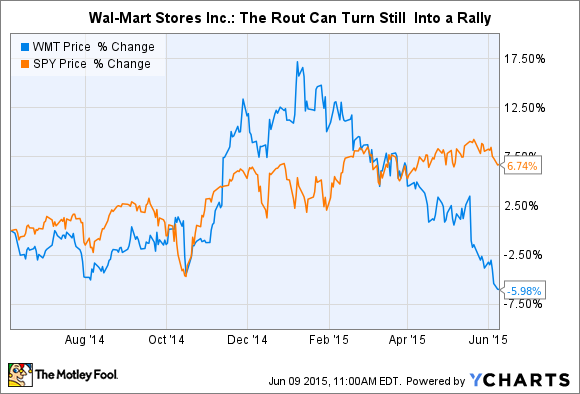

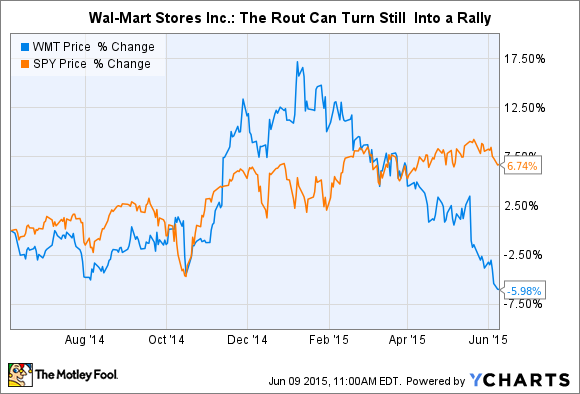

Wal-Mart market value took a huge drop on Wednesday. In fact, the worst valuation decline in its history. That decline continued on Thursday. Since the beginning of 2015 Wal-Mart has lost 1/3 of its value. That is an enormous ouch.

But, if you were surprised, you should not have been. The telltale signs that this was going to happen have been there for years. Like most stock market moves, this one just happened really fast. The “herd behavior” of investors means that most people don’t move until some event happens, and then everyone moves at once carrying out the implications of a sea change in thinking about a company’s future.

But, if you were surprised, you should not have been. The telltale signs that this was going to happen have been there for years. Like most stock market moves, this one just happened really fast. The “herd behavior” of investors means that most people don’t move until some event happens, and then everyone moves at once carrying out the implications of a sea change in thinking about a company’s future.

All the way back in October, 2010 I wrote about “The Wal-Mart Disease.” This is the disease of constantly focusing on improving your “core” business, while market shifts around you increasingly make that “core” less relevant, and less valuable. In the case of Wal-Mart I pointed out that an absolute maniacal focus on retail stores and low-cost operations, in an effort to be the low price retailer, was being made obsolete by on-line retailers who had costs that are a fraction of Wal-Mart’s expensive real estate and armies of employees.

At that time WMT was about $54/share. I recommended nobody own the stock.

In May, 2011 I reiterated this problem at Wal-Mart in a column that paralleled the retailer with software giant Microsoft, and pointed out that because of financial machinations not all earnings are equal. I continued to say that this disease would cripple Wal-Mart. Six months had passed, and the stock was about $55.

By February, 2012 I pointed out that the big reorganization at Wal-Mart was akin to re-arranging deck chairs on a sinking ship and said nobody should own the stock. It was up, however, trading at $61.

At the end of April, 2012 the Wal-Mart Mexican bribery scandal made the press, and I warned investors that this was a telltale sign of a company scrambling to make its numbers – and pushing the ethical (if not legal) envelope in trying to defend and extend its worn out success formula. The stock was $59.

Then in July, 2014 a lawsuit was filed after an overworked Wal-Mart truck driver ran into a car killing James McNair and seriously injuring comedian Tracy Morgan. Again, I pointed out that this was a telltale sign of an organization stretching to try and make money out of a business model that was losing its ability to sustain profits. Market shifts were making it ever harder to keep up with emerging on-line competitors, and accidents like this were visible cracks in the business model. But the stock was now $77. Most investors focused on short-term numbers rather than the telltale signs of distress.

In January, 2015 I pointed out that retail sales were actually down 1% for December, 2014. But Amazon.com had grown considerably. The telltale indication of a rotting traditional retail brick-and-mortar approach was showing itself clearly. Wal-Mart was hitting all time highs of around $87, but I reiterated my recommendation that investors escape the stock.

By July, 2015 we learned that the market cap of Amazon now exceeded that of Wal-Mart. Traditional retail struggles were apparent on several fronts, while on-line growth remained strong. Bigger was not better in the case of Wal-Mart vs. Amazon, because bigger blinded Wal-Mart to the absolute necessity for changing its business model. The stock had fallen back to $72.

Now Wal-Mart is back to $60/share. Where it was in January, 2012 and only 10% higher than when I first said to avoid the stock in 2010. Five years up, then down the roller coaster.

From October of 2010 through January, 2015 I looked dead wrong on Wal-Mart. And the folks who commented on my columns here at this journal and on my web site, or emailed me, were profuse in pointing out that my warnings seemed misguided. Wal-Mart was huge, it was strong and it would dominate was the feedback.

But I kept reiterating the point that long-term investors must look beyond short-term reported sales and earnings. Those numbers are subject to considerable manipulation by management. Further, short-term operating actions, like shorter hours, lower pay, reduced benefits, layoffs and gouging suppliers can all prop up short-term financials at the expense of recognizing the devaluation of the company’s long-term strategy.

Investors buy and hold. They hold until they see telltale signs of a company not adjusting to market shifts. Short-term traders will say you could have bought in 2010, or 2012, and held into 2014, and then jumped out and made a profit. But, who really can do that with forethought? Market timing is a fools game. The herd will always stay too long, then run out too late. Timers get trampled in the stampede more often than book gains.

In this week’s announcement Wal-Mart executives provided more telltale signs of their problems, and the fact that they don’t know how to fix them, and therefore won’t.

- Wal-Mart is going to spend $20B to buy back stock in order to prop up the price. This is the most obvious sign of a company that doesn’t know how to keep up its valuation by growing profits.

- Wal-Mart will spend $11B on sprucing up and opening stores. Really. The demand for retail space has been declining at 4-6%/year for a decade, and retail business growth is all on-line, yet Wal-Mart is still massively investing in its old “core” business.

- Wal-Mart will spend $1.1B on e-commerce. That is the proverbial “drop in the competitors bucket.” Amazon.com alone spent $8.9B in 2014 growing its on-line business.

- Wal-Mart admits profits will decline in the next year. It is planning for a growth stall. Yet, we know that statistically only 7% of companies that have a growth stall ever go on to maintain a consistent growth rate of a mere 2%. In other words, Wal-Mart is projecting the classic “hockey stick” forecast. And investors are to believe it?

The telltale signs of an obsolete business model have been present at Wal-Mart for years, and continue.

In 2003 Sears Holdings was $25/share. In 2004 Sears bought K-Mart, and the stock was $40. I said don’t go near it, as all the signs were bad and the merger was ill-conceived. Despite revenue declines, consistent losses, a revolving door at the executive offices and no sign of any plan to transform the battered, outdated retail giant against growing on-line competition investors believed in CEO Ed Lampert and bid the stock up to $77 in early 2011. (I consistently pointed out the telltale signs of trouble and recommended selling the stock.)

By the end of 2012 it was clear Sears was irrelevant to holiday shoppers, and the stock was trading again at $40. Now, SHLD is $25 – where it was 12 years ago when Mr. Lampert started his machinations. Again, only a market timer could have made money in this company. For long-term investors, the signs were all there that this was not a place to put your money if you want to have capital growth for retirement.

There will be plenty who will call Wal-Mart a “value” stock and recommend investors “buy on weakness.” But Wal-Mart is no value. It is becoming obsolete, irrelevant – increasingly looking like Sears. The likelihood of Wal-Mart falling to $20 (where it was at the beginning of 1998 before it made an 18 month run to $50 more than doubling its value) is far higher than ever trading anywhere near its 2015 highs.

by Adam Hartung | Sep 22, 2015 | Current Affairs, Disruptions, In the Rapids, Innovation

A recent analyst took a look at the impact of electric vehicles (EVs) on the demand for oil, and concluded that they did not matter. In a market of 95million barrels per day production, electric cars made a difference of 25,000 to 70,000 barrels of lost consumption; ~.05%.

You can’t argue with his arithmetic. So far, they haven’t made any difference.

But then he goes on to say they won’t matter for another decade. He forecasts electric vehicle sales grow 5-fold in one decade, which sounds enormous. That is almost 20% growth year over year for 10 consecutive years. Admittedly, that sounds really, really big. Yet, at 1.5million units/year this would still be only 5% of cars sold, and thus still not a material impact on the demand for gasoline.

But then he goes on to say they won’t matter for another decade. He forecasts electric vehicle sales grow 5-fold in one decade, which sounds enormous. That is almost 20% growth year over year for 10 consecutive years. Admittedly, that sounds really, really big. Yet, at 1.5million units/year this would still be only 5% of cars sold, and thus still not a material impact on the demand for gasoline.

This sounds so logical. And one can’t argue with his arithmetic.

But one can argue with the key assumption, and that is the growth rate.

Do you remember owning a Walkman? Listening to compact discs? That was the most common way to listen to music about a decade ago. Now you use your phone, and nobody has a walkman.

Remember watching movies on DVDs? Remember going to Blockbuster, et.al. to rent a DVD? That was common just a decade ago. Now you likely have shelved the DVD player, lost track of your DVD collection and stream all your entertainment. Bluckbuster, infamously, went bankrupt.

Do you remember when you never left home without your laptop? That was the primary tool for digital connectivity just 6 years ago. Now almost everyone in the developed world (and coming close in the developing) carries a smartphone and/or tablet and the laptop sits idle. Sales for laptops have declined for 5 years, and a lot faster than all the computer experts predicted.

Markets that did not exist for mobile products 10 years ago are now huge. Way beyond anyone’s expectations. Apple alone has sold over 48million mobile devices in just 3 months (Q3 2015.) And replacing CDs, Apple’s iTunes was downloading 21million songs per day in 2013 (surely more by now) reaching about 2billion per quarter. Netflix now has over 65million subscribers. On average they stream 1.5hours of content/day – so about 1 feature length movie. In other words, 5.85billion streamed movies per quarter.

What has happened to old leaders as this happened? Sony hasn’t made money in 6 years. Motorola has almost disappeared. CD and DVD departments have disappeared from stores, bankrupting Circuit City and Blockbuster, and putting a world of hurt on survivors like Best Buy.

The point? When markets shift, they often shift a lot faster than anyone predicts. 20%/year growth is nothing. Growth can be 100% per quarter. And the winners benefit unbelievably well, while losers fall farther and faster than we imagine.

Tesla was barely an up-and-comer in 2012 when I said they would far outperform GM, Ford and Toyota. The famous Bob Lutz, a long-term widely heralded auto industry veteran chastised me in his own column “Tesla Beating Detroit – That’s Just Nonsense.”

Mr. Lutz said I was comparing a high-end restaurant to McDonald’s, Wendy’s and Pizza Hut, and I was foolish because the latter were much savvier and capable than the former. He should have used as his comparison Chipotle, which I predicted would be a huge winner in 2011. Those who followed my advice would have made more money owning Chipotle than any of the companies Mr. Lutz preferred.

The point? Market shifts are never predicted by incumbents, or those who watch history. The rate of change when it happens is so explosive it would appear impossible to achieve, and far more impossible to sustain. The trends shift, and one market is rapidly displaced by another.

While GM, Ford and Toyota struggle to maintain their mediocrity, Tesla is winning “best car” awards one after another – even “breaking” Consumer Reports review system by winning 103 points out of a maximum 100, the independent reviewer liked the car so much. Tesla keeps selling 100% of its production, even at its +$100K price point.

So could the market for EVs wildly grow? BMW has announced it will make all models available as electrics within 10 years, as it anticipates a wholesale market shift by consumers promoted by stricter environmental regulations. Petroleum powered car sales will take a nosedive.

The International Energy Agency (IEA) points out that EVs are just .08% of all cars today. And of the 665,000 on the road, almost 40% are in the USA, where they represent little more than a rounding error in market share. But there are smaller markets where EV sales have strong share, such as 12% in Norway and 5% in the Netherlands.

So what happens if Tesla’s new lower priced cars, and international expansion, creates a sea change like the iPod, iPhone and iPad? What happens if people can’t get enough of EVs? What happens if international markets take off, due to tougher regulations and higher petrol costs? What happens if people start thinking of electric cars as mainstream, and gasoline cars as old technology — like two-way radios, VCRs, DVD players, low-definition picture tube TVs, land line telephones, fax machines, etc?

What if demand for electric cars starts doubling each quarter, and grows to 35% or 50% of the market in 10 years? If so, what happens to Tesla? Apple was a nearly bankrupt, also ran, tiny market share company in 2000 before it made the world “i-crazy.” Now it is the most valuable publicly traded company in the world.

Already awash in the greatest oil inventory ever, crude prices are down about 60% in the last year. Oil companies have already laid-off 50,000 employees. More cuts are planned, and defaults expected to accelerate as oil companies declare bankruptcy.

It is not hard to imagine that if EVs really take off amidst a major market shift, oil companies will definitely see a precipitous decline in demand that happens much faster than anticipated.

To little Tesla, which sold only 1,500 cars in 2010 could very well be positioned to make an enormous difference in our lives, and dramatically change the fortunes of its shareholders — while throwing a world of hurt on a huge company like Exxon (which was the most valuable company in the world until Apple unseated it.)

[Note: I want to thank Andreas de Vries for inspiring this column and assisting its research. Andreas consults on Strategy Management in the Oil & Gas industry, and currently works for a major NOC in the Gulf.]

by Adam Hartung | Sep 11, 2015 | Current Affairs, Defend & Extend, In the Swamp, Leadership

Jeff Smisek, CEO of United Continental Holdings, was fired this week. It appears he was making deals with public officials (specifically the Chairman of the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey) to keep personally favored flights of politicians in the air, even when unprofitable, in a quid-pro-quo exchange for government subsidies to move a taxiway and better airport transit.

Wow, horse-trading of the kind that put the governor of Illinois in the penitentiary.

But you have to ask yourself, couldn’t you see it coming? Or are we just so used to lousy leadership that we think there’s no end to it?

But you have to ask yourself, couldn’t you see it coming? Or are we just so used to lousy leadership that we think there’s no end to it?

United has been beset with a number of problems. Since Mr. Smisek organized the merger of Continental (his former employer) with United, creating the world’s largest airline at the time, things have not gone well. Since announcing the merger in 2010, more has gone wrong than right at United:

The merged airline didn’t start in a great position. It was in 2009 that a budding musician watched United baggage handlers destroy his guitar, leading to a series of videos on bad customer service that took to the top of YouTube and iTunes and his book on the culture of customer abuse at United underscored a major PR nightmare.

How could things seem to constantly become worse? It was clear that at the top, United’s leadership cared only about cost control (ironically code named Project Quality.) Operational efficiency was seen as the only strategy, and it did not matter how much this strategy disaffected employees, suppliers or customers. In 2013 United ranked dead last in the quality ranking of all airlines by Wichita State University, and the airline replied by saying it really didn’t care.

The power of thinking that if you focus on pennies and nickels the quarters and dollars will take care of themselves is strong. It encourages you be very focused on details, even myopic, and operate your business very narrowly. And it can set you up to make really dumb mistakes, like possibly trading airline flights for construction subsidies.

Focus, focus, focus often leads to being blind, blind, blind to the world around you.

There were ample signs of all the things going wrong at United, and the need for a change. The open question is why it took a criminal investigation into bribing government officials for the airline’s Board to fire the CEO? Bad performance apparently didn’t matter? Do you have to be an accused lawbreaker to be shown the door?

The story broke in February, so the Board has had a few months to find a replacement CEO. Mr. Oscar Munoz will now take the reigns. But one has to wonder if he is up for the challenges. As a former railroad President, his world of relationships was much smaller than the millions of customers and 84,000 employees at United.

United’s top brass has a serious need “to get over itself.” United’s internal focus, driven by costs, has disenfranchised its brand embassadors, its customer base, and many industry analysts.

United needs to become a lot clearer about what customers really need and want. Years of overly simplistic “all customers care about is price” has commoditized United’s approach to air travel. Customers have been smart enough to see through lower seat prices, only to be stuck with seat assignment and baggage fees raising total trip cost. And charging for everything on the plane, including cheesy TV shows, has customers wondering just how far from Spirit Airlines’ approach United would drift before someone reminded leadership what their customers want and why they used to choose United.

Unfortunately, it is a bit unsettling that CEO Munoz said his first action will be to take 90 days “traveling the system and listening and talking to our people and working with our management team.” Sounds like a lot more internal focus. Spending more time talking to customers at United’s hubs, and seeing how they are treated from check-in to baggage, might do him a lot more good.

United became big via acquisition. That is much different than building an airline, like say Southwest did. Growth via purchase is not the same as growth via loyal customers and an attractive brand proposition. United has clearly lost its way. It has a lot of problems to solve, but first among them should be understanding what customers want. Then designing the model to profitably deliver it.

by Adam Hartung | Aug 21, 2015 | Current Affairs, Disruptions, Leadership, Transparency

How clearly I remember. I was in the finals of my third grade arithmetic competition. Two of us at the chalkboard, we both scribbled the numbers read to us as fast as we could, did the sum and whirled to look at the judges. Only my competitor was a hair quicker than me, so I was not the winner.

As we walked to the car my mother was quite agitated. “You lost to a GIRL” she said; stringing out that last word like it was some filthy moniker not fit for decent company to here. Born in 1916, to her it was a disgrace that her only son lost a competition to a female.

But it hit me like a tsunami wall. I had underestimated my competitor. And that was stupid of me. I swore I would never again make the mistake of thinking I was better than someone because of my male gender, white skin color, protestant christian upbringing or USA nationality. If I wanted to succeed I had to realize that everyone who competes gets to the end by winning, and they can/will beat me if I don’t do my best.

This week 1st Lt. Shaye Haver, 25, and Capt. Kristen Griest, 26, graduated Army Ranger training. Maybe the toughest military training in the world. And they were awarded their tabs because they were good – not because they were women.

This week 1st Lt. Shaye Haver, 25, and Capt. Kristen Griest, 26, graduated Army Ranger training. Maybe the toughest military training in the world. And they were awarded their tabs because they were good – not because they were women.

In retrospect, it is somewhat incredible that it took this long for our country to begin training all people at this level. If someone is good, why not let them compete? In what way is it smart to hold back someone from competing based on something as silly as their skin color, gender, religious beliefs or sexual orientation?

Our country, in fact much of mankind, has had a long history of holding people back from competing. Those in power like to stay in power, and will use about any tool they can to maintain the status quo – and keep themselves in charge. They will use private clubs, secret organizations, high investment rates, difficult admission programs, laws and social mores to “keep each to his own kind” as I heard far too often throughout my youth.

As I went to college I never forgot my 3rd grade experience, and I battled like crazy to be at the top of every class. It was clear to me there were a lot of people as smart as I was. If I wanted to move forward, it would be foolish to expect I would rise just because the status quo of the time protected healthy white males. There were plenty of women, people of color, and folks with different religions who wanted the spot I wanted – and they would win that spot. Maybe not that day, but soon enough.

In the 1980s I did a project for The Boston Consulting Group in South Africa. As I moved around that segregated apartheid country it was clear to me that those supporting the status quo did so out of fear. They weren’t superior to the native South Africans. But the only way they could maintain their lifestyle was to prohibit these other people from competing.

And that proved to be untenable. The status quo fell, and when it did many of European extraction quickly fled – unable to compete with those they long kept from competing.

In the last 30 years we’ve coined the term “diversity” for allowing people to compete. I guess that is a nice, politically favorable way to say we must overcome the status quo tools used to hold people back. But the drawback is that those in power can use the term to imply someone is allowed to compete, or even possibly wins, only because they were given “special permission” which implies “special terms.”

That is unfortunate, because most of the time the only break these folks got was being allowed to, finally, compete. Once in the competition they frequently have to deal with lots of attacks – even from their own teammates. Jim Thorpe was a Native American who mesmerized Americans by winning multiple Gold Medals at the 1912 Olympics, and embarrassing the Germans then preaching national/racial superiority as they planned the launch of WW1. But, once back on American soil it didn’t take long for his own countrymen to strip Mr. Thorpe of his medals, unhappy that he was an “Indian” rather than a white man. He tragically died a homeless alcoholic.

And never forget all the grief Jackie Robinson bore as the first African-American professional athlete. Branch Rickey overcame the status quo police by giving Mr. Robinson a chance to play in the all-white professional major league baseball. But Mr. Robinson endured years of verbal and physical abuse in order to continue competing, well over and beyond anything suffered by any of his white peers. (For a taste of the difficulties catch the HBO docudrama “42.”)

In 2014, 4057 highly trained, fit soldiers entered Ranger training. 1,609 (40%) graduated. In this latest class 364 soldiers started; 136 graduated (37%.) Officers Griest and Haver are among the very best, toughest, well trained, well prepared, well armed and smartest soldiers in the entire world. (If you have any doubts about this I encourage you to watch the HBO docudrama “Lone Survivor” about Army Rangers trapped behind enemy lines in Afghanistan.)

Officers Griest and Haver are like every other Ranger. They are not “diverse.” They are good. Every American soldier who recognizes the strength of character and tenacity it took for them to become Rangers will gladly follow their orders into battle. They aren’t women Rangers, they are Rangers.

When all Americans learn the importance of this lesson, and begin to see the world this way, we will allow our best to rise to the top. And our history of finding and creating great leadership will continue.

by Adam Hartung | Aug 16, 2015 | Current Affairs, Disruptions, Leadership, Transparency

Last week the National Association of Corporate Directors (NACD) pre-released some results of its 2015–2016 Public Company Governance Survey. One major finding is that the makeup of Boards is changing, for the betterment of investors – and most likely everyone else in business.

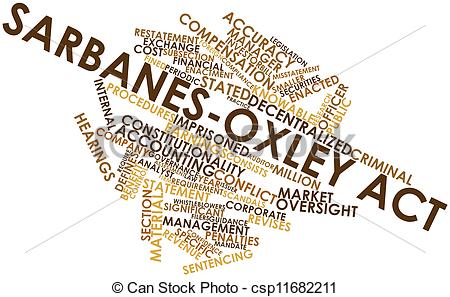

Boards once had members that almost never changed. Little was required of Directors, and accountability for Board members was low. Since passage of the Securities Act of 1933, little had been required of Board members other than to applaud management and sign-off on the annual audit. And there was nothing investors could do if a Board “checked out,” even in the face of poorly performing management.

But this has changed. According to NACD, 72% of public boards reported they either added or changed a director in the last year. That is up from 64% in the previous year. Board members, and especially committee chairs, are spending a lot more time governing corporations. As a result “retiring in job” has become nearly impossible, and Board diversity is increasingly quite quickly. And increased Board diversity is considered good for business.

Remember Enron, Arthur Anderson, Worldcom and Tyco? At the century’s turn executives in large companies were working closely with their auditors to undertake risky business propositions yet keep these transactions and practices “off the books.” As these companies increasingly hired their audit firm to also provide business consulting, the auditors found it easier to agree with aggressive accounting interpretations that made company financials look better. Some companies went so far as to lie to investors and regulators about their business, until their companies failed from the risks and unlawful activities.

As a result Congress passed the Sarbanes Oxley act in 2002 (SOX,) which greatly increased the duties of Board Directors – as well as penalties if they failed to meet their duties. This law required Boards to implement procedures to unearth off-balance sheet items, and potential illegal activities such as bribing foreign officials or failing to meet industry reporting requirements for health and safety. Boards were required to know what internal controls were in place, and were held accountable for procedures to implement those controls effectively. And they were also required to make sure the auditors were independent, and not influenced by management when undertaking accounting and disclosure reviews. These requirements were backed up by criminal penalties for CEOs and CFOs that fiddled with financial statements or retaliated on whistle blowers – and Boards were expected to put in place systems to discover possibly illegal executive behavior.

As a result Congress passed the Sarbanes Oxley act in 2002 (SOX,) which greatly increased the duties of Board Directors – as well as penalties if they failed to meet their duties. This law required Boards to implement procedures to unearth off-balance sheet items, and potential illegal activities such as bribing foreign officials or failing to meet industry reporting requirements for health and safety. Boards were required to know what internal controls were in place, and were held accountable for procedures to implement those controls effectively. And they were also required to make sure the auditors were independent, and not influenced by management when undertaking accounting and disclosure reviews. These requirements were backed up by criminal penalties for CEOs and CFOs that fiddled with financial statements or retaliated on whistle blowers – and Boards were expected to put in place systems to discover possibly illegal executive behavior.

In short, Sarbanes Oxley increased transparency for investors into the corporation. And it made Boards responsible for compliance. The demands on Board Directors suddenly skyrocketed.

In reaction to the failure of Lehman Brothers and the almost total bank collapse of 2008, Congress passed the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act in 2010. Most of this complex legislation dealt with regulating the financial services industry, and providing more protections for consumers and American taxpayers from risky banking practices. But also included in Dodd-Frank were greater transparency requirements, such as details of executive compensation and how compensation was linked to company performance. Companies had to report such things as the pay ratio of CEO pay to average employee compensation (final rules issued last week,) and had to provide for investors to actually vote on executive compensation (called “say on pay.”) And responsibility for implementing these provisions, across all industries, fell again on the Board of Directors.

Thus, after 13 years of regulatory implementation, we are seeing change in corporate governance. What many laypeople thought was the Board’s job from 1940-2000 is finally, actually becoming their job. Real responsibility is now on the Directors’ shoulders. They are accountable. And they can be held responsible by regulators.

The result is a sea change in how Boards behave, and the beginnings of big change in Board composition. Board members are leaving in record numbers. Unable to simply hang around and collect a check for doing little, more are retiring. The average age is lowering. And diversity is increasing as more women, and people of color as well as non-European family histories are being asked onto Boards. Recognizing the need for stronger Boards to make sure companies comply with regulations they are less inclined to idly stand by and watch management. Instead, Boards are seeking talented people with diverse backgrounds to ask better questions and govern more carefully.

Most business people wax eloquently about the negative effect of regulations. It is easy to find academic studies, and case examples, of the added cost incurred due to higher regulation. But what many people fail to recognize are the benefits. Thanks to SOX and Dodd-Frank companies are far more transparent than ever in history, and transparency is increasing – much to the benefit of investors, suppliers, customers and communities. And corporate governance of everything from accounting to compensation to industry compliance is far more extensive, and better. Because Boards are responsible, they are stronger, more capable and improving at a rate previously unseen – with dramatic improvement in diversity. And we can thank Congress for the legislation which demanded better Board performance – to the betterment of all business.

by Adam Hartung | Jul 8, 2015 | Current Affairs, Defend & Extend, In the Whirlpool, Leadership, Lock-in, Web/Tech

Microsoft announced today it was going to shut down the Nokia phone unit, take a $7.6B write-off (more than the $7.2B they paid for it,) and lay off another 7,800 employees. That makes the layoffs since CEO Nadella took the reigns almost 26,000. Finding any good news in this announcement is a very difficult task.

Unfortunately, since taking over as Microsoft’s #1 leader, Mr. Nadella has been remarkably predictable. Like his peer CEOs who take on the new role, he has slashed and burned employment, shut down at least one big business, taken massive write-offs, and undertaken at least one wildly overpriced acquisition (Minecraft) that is supposed to be a game changer for the company. He apparently picked up the “Turnaround CEO Playbook” after receiving the job and set out on the big tasks!

Unfortunately, since taking over as Microsoft’s #1 leader, Mr. Nadella has been remarkably predictable. Like his peer CEOs who take on the new role, he has slashed and burned employment, shut down at least one big business, taken massive write-offs, and undertaken at least one wildly overpriced acquisition (Minecraft) that is supposed to be a game changer for the company. He apparently picked up the “Turnaround CEO Playbook” after receiving the job and set out on the big tasks!

Yet he still has not put forward a strategy that should encourage investors, employees, customers or suppliers that the company will remain relevant long-term. Amidst all these big tactical actions, it is completely unclear what the strategy is to remain a viable company as customers move, quickly and in droves, to mobile devices using competitive products.

I predicted here in this blog the week Steve Ballmer announced the acquisition of Nokia in September, 2013 that it was “a $7.2B mistake.” I was off, because in addition to all the losses and restructuring costs Microsoft endured the last 7 quarters, the write off is $7.6B. Oops.

Why was I so sure it would be a mistake? Because between 2011 and 2013 Nokia had already lost half its market share. CEO Elop, who was previously a Microsoft senior executive, had committed Nokia completely to Windows phones, and the results were already catastrophic. Changing ownership was not going to change the trajectory of Nokia sales.

Microsoft had failed to build any sort of developer community for Windows 8 mobile. Developers need people holding devices to buy their software. Nokia had less than 5% share. Why would any developer build an app for a Windows phone, when almost the entire market was iOS or Android? In fact, it was clear that developing rev 2, 3, and 4 of an app for the major platforms was far more valuable than even bothering to port an app into Windows 8.

Nokia and Windows 8 had the worst kind of tortuous whirlpool – no users, so no developers, and without new (and actually unique) software there was nothing to attract new users. Microsoft mobile simply wasn’t even in the game – and had no hope of winning. It was already clear in June, 2012 that the new Windows tablet – Surface – was being launched with a distinct lack of apps to challenge incumbents Apple and Samsung.

By January, 2013 it was also clear that Microsoft was in a huge amount of trouble. Where just a few years before there were 50 Microsoft-based machines sold for every competitive machine, by 2013 that had shifted to 2 for 1. People were not buying new PCs, but they were buying mobile devices by the shipload – literally. And there was no doubt that Windows 8 had missed the mobile market. Trying too hard to be the old Windows while trying to be something new made the product something few wanted – and certainly not a game changer.

A year ago I wrote that Microsoft has to win the war for developers, or nothing else matters. When everyone used a PC it seemed that all developers were writing applications for PCs. But the world shifted. PC developers still existed, but they were not able to grow sales. The developers making all the money were the ones writing for iOS and Android. The growth was all in mobile, and Microsoft had nothing in the game. Meanwhile, Apple and IBM were joining forces to further displace laptops with iPads in commercial/enterprise uses.

Then we heard Windows 10 would change all of that. And flocks of people wrote me that a hybrid machine, both PC and tablet, was the tool everyone wanted. Only we continue to see that the market is wildly indifferent to Windows 10 and hybrids.

Imagine you write with a fountain pen – as most people did 70 years ago. Then one day you are given a ball point pen. This is far easier to use, and accomplishes most of what you want. No, it won’t make the florid lines and majestic sweeps of a fountain pen, but wow it is a whole lot easier and a darn site cheaper. So you keep the fountain pen for some uses, but mostly start using the ball point pen.

Then the fountain pen manufacturer says “hey, I have a contraption that is a ball point pen, sort of, and a fountain pen, sort of, combined. It’s the best of all worlds.” You would likely look at it, but say “why would I want that. I have a fountain pen for when I need it. And for 90% of the stuff I write the ball point pen is great.”

That’s the problem with hybrids of anything – and the hybrid tablet is no different. The entrenched sellers of old technology always think a hybrid is a good idea. But once customers try the new thing, all they want are advancements to the new thing. (Just look at the interest in Tesla cars compared to the stagnant sales of hybrid autos.)

And we’re up to Surface 3 now. When I pointed out in January, 2013 that the markets were rapidly moving away from Microsoft I predicted Surface and Surface Pro would never be important products. Reader outcry at that time from Microsoft devotees was so great that Forbes editors called me on the carpet and told me I lacked the data to make such a bold prediction. But I stuck by my guns, we changed some language so it was less blunt, and the article ran.

Two and a half years later and we’re up to rev number Surface 3. And still, almost nobody is using the product. Less than 5% market share. Right again. It wasn’t a technology prediction, it was a market prediction. Lacking app developers, and a unique use, the competition was, and remains, simply too far out front.

Windows 10 is, unfortunately, a very expensive launch. And to get people to use it Microsoft is giving it away for free. The hope is then users will hook onto the cloud-based Office 365 and Microsoft’s Azure cloud services. But this is still trying to milk the same old cow. This approach relies on people being completely unwilling to give up using Windows and/or Office. And we see every day that millions of people are finding alternatives they like just fine, thank you very much.

Gamers hated me when I recommended Microsoft should give (for free) xBox to Nintendo. Unfortunately, I learned few gamers know much about P&Ls. They all assumed Microsoft made a fortune in gaming. But anyone who’s ever looked at Microsoft’s financial filings knows that the Entertainment Division, including xBox, has been a giant money-sucking hole. If they gave it away it would save money, and possibly help leadership figure out a strategy for profitable growth.

Unfortunately, Microsoft bought Minecraft, in effect “doubling down” on the bet. But regardless of how well anyone likes the products, Microsoft is not making money. Gaming is a bloody war where Sony and Microsoft keep battling, and keep losing billions of dollars. The odds of ever earning back the $2.5B spent on Minecraft is remote.

The greater likelihood is that as write offs continue to eat away at profits, and as markets continue evolving toward mobile products offered by competitors hurting “core” Microsoft sales, CEO Nadella will eventually have to give up on gaming and undertake another Nokia-like event.

All investors risk looking at current events to drive decision-making. When Ballmer was sacked and Nadella given the CEO job the stock jumped on euphoria. But the last 18 months have shown just how bad things are for Microsoft. It is a near monopolist in a market that is shrinking. And so far Mr. Nadella has failed to define a strategy that will make Microsoft into a company that does more than try to milk its heritage.

I said the giant retailer Sears Holdings would be a big loser the day Ed Lampert took control of the company. But hope sprung eternal, and investors jumped on the Sears bandwagon, believing a new CEO would magically improve a worn out, locked-in company. The stock went up for over 2 years. But, eventually, it became clear that Sears is irrelevant and the share price increase was unjustified. And the stock tanked.

Microsoft looks much the same. The actions we see are attempts to defend & extend a gloried history. But they don’t add up to a strategy to compete for the future. HoloLens will not be a product capable of replacing Windows plus Office revenues. If developers are attracted to it enough to start writing apps. Cortana is cool, but it is not first. And competitive products have so much greater usage that developer learning curve gains are wildly faster. These products are not game changers. They don’t solve large, unmet needs.

And employees see this. As I wrote in my last column, it is valuable to listen to employees. As the bloom fell off the rose, and Nadella started laying people off while freezing pay, employee support of him declined dramatically. And employee faith in leadership is far lower than at competitors Apple and Google.

As long as Microsoft keeps playing catch up, we should expect more layoffs, cost cutting and asset sales. And attempts at more “hail Mary” acquisitions intended to change the company. All of which will do nothing to grow customers, provide better jobs for employees, create value for investors or greater revenue opportunities for suppliers.

by Adam Hartung | Jun 22, 2015 | Current Affairs, Defend & Extend, Lock-in

The Economic Policy Institute issued its most recent report on CEO pay yesterday, and the title makes the point clearly “Top CEOs Make 300 Times More than Typical Workers.” CEOs of the 350 largest US public companies now average $16,300,000 in compensation, while typical workers average about $53,000.

Actually, it is kind of remarkable that this stat keeps grabbing attention. The 300 multiple has been around since 1998. The gap actually peaked in 2000 at almost 376. There has been whipsawing, but it has averaged right around 300 for 15 years.

The big change happened in the 1990s. In 1965 the multiple was 20, and by 1978 it had risen only to 30. The next decade, going into 1990 saw the multiple rise to 60. But then from 1990 to 2000 it jumped from 60 to well over 300 – where it has averaged since. So it was long ago that large company CEO pay made its huge gains, and it such compensation has now become the norm.

But this does rile some folks. After all, when a hired CEO makes more in a single workday (based on 5 day week) than the worker does in an entire year, justification does become a bit difficult. And when we recognize that this has happened in just one generation it is a sea change.

If average workers are angry, and some investors are angry, and politicians are increasingly speaking negatively about the topic why does CEO pay remain so high?

If average workers are angry, and some investors are angry, and politicians are increasingly speaking negatively about the topic why does CEO pay remain so high?

Reason 1 – Because they can

CEOs are like kings. They aren’t elected to their position, they are appointed. Usually after several years of grueling internecine political warfare, back-stabbing colleagues and gerrymandering the organization. Once in the position, they pretty much get to set their own pay.

Who can change the pay? Ostensibly the Board of Directors. But who makes up most Boards? CEOs (and former CEOs). It doesn’t do any Board member’s reputation any good with his peers to try and cut CEO pay. You certainly don’t want your objection to “Joe’s” pay coming up when its time to set your pay.

Honestly, if you could set your own pay what would it be? I reckon most folks would take as much as they could get.

Reason 2 – the Lake Wobegon effect

NPR (National Public Radio) broadcasts a show about a fictional, rural Minnesota town called Lake Wobegon where “the women are strong, the men are good-looking, and all of the children are above average.”

Nice joke, until you apply it to CEOs. The top 350 CEOs are accomplished individuals. Which 175 are above average, and which 175 are below average? Honestly, how does a Board judge? Who has the ability to determine if a specific CEO is above average, or below average?

So when the “average” CEO pay is announced, any CEO would be expected to go to the Board, tell them the published average and ask “well, don’t you think I’ve done a great job? Don’t you think I’m above average? If so, then shouldn’t I be compensated at some percentage greater than average?”

Repeat this process 350 times, every year, and you can see how large company CEO pay keeps going up. And data in the EPI report supports this. Those who have the greatest pay increase are the 20% who are paid the lowest. The group with the second greatest pay increase are the 20% in the next to lowest paid quintile. These lower paid CEOs say “shouldn’t I be paid at least average – if not more?”

The Board agrees to this logic, since they think the CEO is doing a good job (otherwise they would fire him.) So they step up his, or her, pay. This then pushes up the average. And every year this process is repeated, pushing pay higher and higher and higher.

Oh, and if you replace a CEO then the new person certainly is not going to take the job for below-average compensation. They are expected to do great things, so they must be brought in with compensation that is up toward the top. The recruiters will assure the Board that finding the right CEO is challenging, and they must “pay up” to obtain the “right talent.” Again, driving up the average.

Reason 3 – It’s a “King’s Court”

Today’s large corporations hire consultants to evaluate CEO performance, and design “pay for performance” compensation packages. These are then reviewed by external lawyers for their legality. And by investment bankers for their acceptability to investors. These outside parties render opinions as to the CEO’s performance, and pay package, and overall pay given.

Unfortunately, these folks are hired by the CEO and his Board to render these opinions. Meaning, the person they judge is the one who pays them. Not the employees, not a company union, not an investor group and not government regulators. They are hired and paid by the people they are judging.

Thus, this becomes something akin to an old fashioned King’s Court. Who is in the Boardroom that gains if they object to the CEO pay package? If the CEO selects the Board (and they do, because investors, employees and regulators certainly don’t) and then they collectively hire an outside expert, does anyone in the room want that expert to say the CEO is overpaid?

If they say the CEO is overpaid, how do they benefit? Can you think of even one way? However, if they do take this action – say out of conscious, morality, historical comparisons or just obstreperousness – they risk being asked to not do future evaluations. And, even worse, such an opinion by these experts places their clients (the CEO and Board) at risk of shareholder lawsuits for not fulfilling their fiduciary responsibility. That’s what one would call a “lose/lose.”

And, let’s not forget, that even if you think a CEO is overpaid by $10million or $20million, it is still a rounding error in the profitability of these 350 large companies. Financially, to the future of the organization, it really does not matter. Of all the issues a Board discusses, this one is the least important to earnings per share. When the Board is considering the risks that could keep them up at night (cybersecurity, technology failure, patent infringement, compliance failure, etc.) overpaying the CEO is not “up the list.”

The famed newsman Robert Krulwich identified executive compensation as an issue in the 1980s. He pointed out that there were no “brakes” on executive compensation. There is no outside body that could actually influence CEO pay. He predicted that it would rise dramatically. He was right.

The only apparent brake would be government regulation. But that is a tough sell. Do Americans want Congress, or government bureaucrats, determining compensation for anyone? Americans can’t even hardly agree on a whether there should be a minimum wage at all, much less where it should be set. Rancor against executive compensation may be high, but it is a firecracker compared to the atomic bomb that would be detonated should the government involve itself in setting executive pay.

Not to mention that since the Supreme Court ruling in the case of Citizens United made it possible for companies to invest heavily in elections, it would be hard to imagine how much company money large company CEOs would spend on lobbying to make sure no such regulation was ever passed.

How far can CEO pay rise? We recently learned that Jamie Dimon, CEO of JPMorganChase, has amassed a net worth of $1.1B. It increasingly looks like there may not be a limit.

It really did not have to happen this way. Yahoo’s troubles were clearly visible, and addressable. But CEO Mayer simply chose to keep doing more of the same, making small improvements to Yahoo’s site and search tool. By keeping Yahoo aligned with its historical Status Quo risk of irrelevance, obsolescence and failure grew quarter-by-quarter.

It really did not have to happen this way. Yahoo’s troubles were clearly visible, and addressable. But CEO Mayer simply chose to keep doing more of the same, making small improvements to Yahoo’s site and search tool. By keeping Yahoo aligned with its historical Status Quo risk of irrelevance, obsolescence and failure grew quarter-by-quarter.