by Adam Hartung | Sep 30, 2014 | Current Affairs, Disruptions, In the Rapids, Innovation, Leadership, Web/Tech

Will the new Apple Pay product, revealed on iPhone 6 devices, succeed? There have been many entries into the digital mobile payments business, such as Google Wallet, Softcard (which had the unfortunate initial name of ISIS,) Square and Paypal. But so far, nobody has really cracked the market as Americans keep using credit cards, cash and checks.

But that looks like it might change, and Apple has a pretty good chance of making Apple Pay a success.

First, a look at some critical market changes. For decades we all thought credit card purchases were secure. But that changed in 2013, and picked up steam in 2014. With regularity we’ve heard about customer credit card data breaches at various retailers and restaurants. Smaller retailers like Shaw’s, Star Markets and Jewel caused some mild concern. But when top tier retailers like Target and Home Depot revealed security problems, across millions of accounts, people really started to notice. For the first time, some people are thinking an alternative might be a good idea, and they are considering a change.

In other words, there is now an underserved market. For a long time people were very happy using credit cards. But now, they aren’t as happy. There are people, still a minority, who are actively looking for an alternative to cash and credit cards. And those people now have a need that is not fully met. That means the market receptivity for a mobile payment product has changed.

Second let’s look at how Paypal became such a huge success fulfilling an underserved market. When people first began on-line buying transactions were almost wholly credit cards. But some customers lacked the ability to use credit cards. These folks had an underserved need, because they wanted to buy on-line but had no payment method (mailing checks or cash was risky, and COD shipments were costly and not often supported by on-line vendors.) Paypal jumped into that underserved market.

Quickly Paypal tied itself to on-line vendors, asking them to support their product. They went less to people who were underserved, and mostly to the infrastructure which needed to support the product. By encouraging the on-line retailers they could expand sales with Paypal adoption, Paypal gathered more and more sites. The 2002 acquisition by eBay was a boon, as it truly legitimized Paypal in minds of consumers and smaller on-line retailers.

After filling the underserved market, Paypal expanded as a real competitor for credit cards by adding people who simply preferred another option. Today Paypal accounts for $1 of every $6 spent on-line, a dramatic statistic. There are 153million Paypal digital wallets, and Paypal processes $203B of payments annually. Paypal supports 26 currencies, is in 203 markets, has 15,000 financial institution partners – all creating growth last year of 19%. A truly outstanding success story.

Back to traditional retail. As mentioned earlier, there is an underserved market for people who don’t want to use cash, checks or credit cards. They seek a solution. But just as Paypal had to obtain the on-line retailer backing to acquire the end-use customer, mobile payment company success relies on getting retailers to say they take that company’s digital mobile payment product.

Here is where Apple has created an advantage. Few end-use customers are terribly aware of retail beacons, the technology which has small (sometimes very small) devices placed in a store, fast food outlet, stadium or other environment which sends out signals to talk to smartphones which are in nearby proximity. These beacons are an “inside retail” product that most consumer don’t care about, just like they don’t really care about the shelving systems or price tag holders in the store.

Launched with iOS 7, Apple’s iBeacon has become the leader in this “recognize and push” technology. Since Apple installed Beacons in its own stores in December, 2013 tens of thousands of iBeacons have been installed in retailers and other venues. Macy’s alone installed 4,000 in 2014. Increasingly, iBeacons are being used by retailers in conjunction with consumer goods manufacturers to identify who is shopping, what they are buying, and assist them with product information, coupons and other purchase incentives.

Thus, over the last year Apple has successfully been courting the retailers, who are the infrastructure for mobile payments. Now, as the underserved payment issue comes to market it is natural for retailers to turn to the company with which they’ve been working on their “infrastructure” products.

Apple has an additional great benefit because it has by far the largest installed base of smartphones, and its products are very consistent. Even though Android is a huge market, and outsells iOS, the platform is not consistent because Android on Samsung is not like Android on Amazon’s Fire, for example. So when a retailer reaches out for the alternative to credit cards, Apple can deliver the largest number of users. Couple that with the internal iBeacon relationship, and Apple is really well positioned to be the first company major retailers and restaurants turn to for a solution – as we’ve already seen with Apple Pay’s acceptance by Macy’s, Bloomingdales, Duane Reed, McDonald’s Staples, Walgreen’s, Whole Foods and others.

This does not guarantee Apple Pay will be the success of Paypal. The market is fledgling. Whether the need is strong or depth of being underserved is marked is unknown. How consumers will respond to credit card use and mobile payments long-term is impossible to gauge. How competitors will react is wildly unpredictable.

But, Apple is very well positioned to win with Apple Pay. It is being introduced at a good time when people are feeling their needs are underserved. The infrastructure is primed to support the product, and there is a large installed base of users who like Apple’s mobile products. The pieces are in place for Apple to disrupt how we pay for things, and possibly create another very, very large market. And Apple’s leadership has a history of successfully managing disruptive product launches, as we’ve seen in music (iPod,) mobile phones (iPhone) and personal technology tools (iPad.)

by Adam Hartung | Sep 25, 2014 | Current Affairs, In the Swamp, In the Whirlpool, Innovation, Sports, Web/Tech

Few businesses fail in a fiery, quick downfall. Most linger along for years, not really mattering to anyone – including customers, suppliers or even investors. They exist, but they aren’t relevant.

When a company is relevant customers are eager for new product releases, and excited to talk to salespeople. Media want to report on the company, its products and its leaders. Investors want to hear about what the company will do next to drive revenues and increase profits.

But when a company loses relevancy, that all disappears. Customers quit paying attention to new products, and salespeople are not given the time of day. The company begs for coverage of its press releases, but few media outlets pay attention because writing about that company produces few readers, or advertisers. Investors lose hope for big gains, and start looking for ways to sell the stock or debt without taking too big a loss, or further depressing valuations.

In short, when a company loses relevancy it is on the downward slope to failure. It may take a long time, but lacking market relevancy the company has practically no hope of increasing revenues or profits, or of creating many new and exciting jobs, or of being a great customer for suppliers. Losing relevancy means the company is headed out of business, it’s just a matter of time. Think Howard Johnson’s, ToysRUs, Sears, Radio Shack, Palm, Hostess, Samsonite, Pierre Cardin, Woolworth’s, International Harvester, Zenith, Sony, Rand McNally, Encyclopedia Britannica, DEC — you get the point.

Many people may not be aware that Microsoft made an exclusive deal with the NFL to provide Surface tablets for coaches and players to use during games, replacing photographs, paper and clipboards for reviewing on-field activities and developing plays. The goal was to up the prestige of Surface, improve its “cool” factor, while showing capabilities that might encourage more developers to write apps for the product and more businesses to buy it.

But things could not have gone worse during the NFL’s launch. Because over and again, announcers kept calling the Surface tablets iPads. Announcers saw the tablet format and simply assumed these were iPads. Or, worse, they did not realize there was any tablet other than the iPad. As more and more announcers made this blunder it became increasingly clear that Apple not only invented the modern tablet marketplace, but that it’s brand completely dominates the mindset of users and potential buyers. iPad has become synonymous with tablet for most people.

In a powerful way, this demonstrates the lack of relevancy Microsoft now has in the personal technology marketplace. Fewer and fewer people are buying PCs as they rely increasingly on mobile devices. Practically nobody cares any more about new releases of Windows or Office. In fact, the American Customer Satisfaction Index reported people think Apple is now considered the best PC maker (the Macintosh.) HP was near the bottom of the list, with Dell, Acer and Toshiba not faring much better.

And in mobile devices, Apple is clearly the king. In its first weekend of sales the new iPhone 6 and 6Plus sold 10million units, blasting past any previous iPhone model launch – and that was without any sales in China and several other markets. The iPhone 4 was considered a smashing success, but iPhone 4 sales of 1.7million units was only 17% of the newest iPhone – and the 9million iPhone 5 sales included China and the lower-priced 5C. In fact, more units could have been sold but Apple ran out of supply, forcing customers to wait. People clearly still want Apple mobile devices, as sales of each successive version brings in more customers and higher sales.

There are many people who cannot imagine a world without Microsoft. And the vast majority of people would think that predicting Microsoft’s demise is considerably premature given its size and cash hoard. But, that looks backward at what Microsoft was, and the assets it previously created, rather than looking forward.

Just how fast can lost relevancy impact a company? Look no further than Blackberry (formerly Research in Motion.) Blackberry was once totally dominant in smartphones. But in the second quarter of last year Apple sold 32.5million units, while Blackberry sold only 1.5million (which was still more than Microsoft sold.)

The complete lack of relevancy was exposed last week when Blackberry launched its new Passport phone alongside Apple’s iPhone 6 actions. While the press was full of articles about the new iPhone, were you even aware of Blackberry’s most recent effort? Did you recall seeing press coverage? Did you read any product reviews? And while Apple was selling record numbers, Blackberry analysts were wondering if the Passport could find a niche with “nostalgic customers” that would sell enough units to keep the company’s hardware unit alive. Reviewers now compare Passport to the market standard, which is the iPhone – and still complain that its use of apps is “confusing.” In a world where most people use their own smartphone, the only reason most people could think of to use a Passport was if their employer told them they were forced to.

Like with Radio Shack, most people have to be reminded that Blackberry still exists. In just a few years Blackberry’s loss of relevancy has made the company and its products a backwater. Now it is quite clear that Microsoft is entering a similar situation. Windows 8 was a weak launch and did nothing to slow the shift to mobile. Microsoft missed the mobile market, and its mobile products are achieving no traction. Even where it has an exclusive use, such as this NFL application, people don’t recognize its products and assume they are the products of the market leader. Microsoft really has become irrelevant in its historical “core” personal technology market – and that should scare its employees and investors a lot.

by Adam Hartung | Aug 6, 2014 | Defend & Extend, In the Whirlpool, Innovation, Lifecycle, Web/Tech

Remember the RAZR phone? Whatever happened to that company?

Motorola has a great tradition. Motorola pioneered the development of wireless communications, and was once a leader in all things radio – as well as made TVs. In an earlier era Motorola was the company that provided 2-way radios (and walkie-talkies for those old enough to remember them) not only for the military, police and fire departments, but connected taxies to dispatchers, and businesses from electricians to plumbers to their “home office.”

Motorola was the company that developed not only the thing in a customer’s hand, but the base stations in offices and even the towers (and equipment on those towers) to allow for wireless communication to work. Motorola even invented mobile telephony, developing the cellular infrastructure as well as the mobile devices. And, for many years, Motorola was the market share leader in cellular phones, first with analog phones and later with digital phones like the RAZR.

But that was the former Motorola, not the renamed Motorola Solutions of today. The last few years most news about Motorola has been about layoffs, downsizings, cost reductions, real estate sales, seeking tenants for underused buildings and now looking for a real estate partner to help the company find a use for its dramatically under-utilized corporate headquarters campus in suburban Chicago.

How did Motorola Solutions become a mere shell of its former self?

Unfortunately, several years ago Motorola was a victim of disruptive innovation, and leadership reacted by deciding to “focus” on its “core” markets. Focus and core are two words often used by leadership when they don’t know what to do next. Too often investment analysts like the sound of these two words, and trumpet management’s decision – knowing that the code implies cost reductions to prop up profits.

But smart investors know that the real implication of “focusing on our core” is the company will soon lose relevancy as markets advance. This will lead to significant sales declines, margin compression, draconian actions to create short-term P&L benefits and eventually the company will disappear.

Motorola’s market decline started when Blackberry used its server software to help corporations more securely use mobile devices for instant communications. The mobile phone transitioned from a consumer device to a business device, and Blackberry quickly grabbed market share as Motorola focused on trying to defend RAZR sales with price reductions while extending the RAZR platform with new gimmicks like additional colors for cases, and adding an MP3 player (called the ROKR.) The Blackberry was a game changer for mobile phones, and Motorola missed this disruptive innovation as it focused on trying to make sustaining improvements in its historical products.

Of course, it did not take long before Apple brought out the iPhone and with all those thousands of apps changed the game on Blackberry. This left Motorola completely out of the market, and the company abandoned its old platform hoping it could use Google’s Android to get back in the game. But, unfortunately, Motorola brought nothing really new to users and its market share dropped to nearly nothing.

The mobile phone business quickly overtook much of the old Motorola 2-way radio business. No electrician or plumber, or any other business person, needed the old-fashioned radios upon which Motorola built its original business. Even police officers used mobile phones for much of their communication, making the demand for those old-style devices rarer with each passing quarter.

But rather than develop a new game changer that would make it once again competitive, Motorola decided to split the company into 2 parts. One would be the very old, and diminishing, radio business still sold to government agencies and niche business applications. This business was profitable, if shrinking. The reason was so that leadership could “focus” on this historical “core” market. Even if it was rapidly becoming obsolete.

The mobile phone business was put out on its own, and lacking anything more than an historical patent portfolio, with no relevant market position, it racked up quarter after quarter of losses. Lacking any innovation to change the market, and desperate to get rid of the losses, in 2011 Motorola sold the mobile phone business – formerly the industry creator and dominant supplier – to Google. Again, the claim was this would allow leadership to even better “focus” on its historical “core” markets.

But the money from the Google sale was invested in trying to defend that old market, which is clearly headed for obsolescence. Profit pressures intensify every quarter as sales are harder to find when people have alternative solutions available from ever improving mobile technology.

As the historical market continued to weaken, and leadership learned it had under-invested in innovation while overspending to try to defend aging solutions, Motorola again cut the business substantially by selling a chunk of its assets – called its “enterprise business” – to a much smaller Zebra Technologies. The ostensible benefit was it would now allow Motorola leadership to even further “focus” on its ever smaller “core” business in government and niche market sales of aging radio technology.

But, of course, this ongoing “focus” on its “core” has failed to produce any revenue growth. So the company has been forced to undertake wave after wave of layoffs. As buildings empty they go for lease, or sale. And nobody cares, any longer, about Motorola. There are no news articles about new products, or new innovations, or new markets. Motorola has lost all market relevancy as its leaders used “focus” on its “core” business to decimate the company’s R&D, product development, sales and employment.

Retrenchment to focus on a core market is not a strategy which can benefit shareholders, customers, employees or the community in which a business operates. It is an admission that the leaders missed a major market shift, and have no idea how to respond. It is the language adopted by leaders that lack any vision of how to grow, lack any innovation, and are quickly going to reduce the company to insignificance. It is the first step on the road to irrelevancy.

Straight from Dr. Christensen’s “Innovator’s Dilemma” we now have another brand name to add to the list of those which were once great and meaningful, but now are relegated to Wikipedia historical memorabilia – victims of their inability to react to disruptive innovations while trying to sustain aging market positions – Motorola, Sears, Montgomery Wards, Circuit City, Sony, Compaq, DEC, American Motors, Coleman, Piper, Sara Lee………..

by Adam Hartung | Jul 28, 2014 | Current Affairs, Defend & Extend, In the Whirlpool, Web/Tech

Over the last couple of weeks big announcements from Apple, IBM and Microsoft have set the stage for what is likely to be Microsoft’s last stand to maintain any sense of personal technology leadership.

Custer Tries Holding Off An Unstoppable Native American Force

To many consumers the IBM and Apple partnership probably sounded semi-interesting. An app for airplane fuel management by commercial pilots is not something most people want. But what this announcement really amounted to was a full assault on regaining dominance in the channel of Value Added Resellers (VARs) and Value Added Dealers (VADs) that still sell computer “solutions” to thousands of businesses. Which is the last remaining historical Microsoft stronghold.

Think about all those businesses that use personal technology tools for things like retail point of purchase, inventory control, loan analysis in small banks, restaurant management, customer data collection, fluid control tracking, hotel check-in, truck routing and management, sales force management, production line control, project management — there is a never-ending list of business-to-business applications which drive the purchase of literally millions of devices and applications. Used by companies as small as a mom-and-pop store to as large as WalMart and JPMorganChase. And these solutions are bundled, sold, delivered and serviced by what is collectively called “the channel” for personal technology.

This “channel” emerged after Apple introduced the Apple II running VisiCalc, and businesses wanted hundreds of these machines. Later, bundling educational software with the Apple II created a near-monopoly for Apple channel partners who bundled solutions for school systems.

But, as the PC emerged this channel shifted. IBM pioneered the Microsoft-based PC, but IBM had long used a direct sales force. So its foray into personal computing did a very poor job of building a powerful sales channel. Even though the IBM PC was Time magazine’s “Man of the Year” in 1982, IBM lost its premier position largely because Microsoft took advantage of the channel opportunity to move well beyond IBM as a supplier.

Microsoft focused on building a very large network of developers creating an enormous variety of business-to-business applications on the Windows+Intel (Wintel) platform. Microsoft created training programs for developers to use its operating system and tools, while simultaneously cultivating manufacturers (such as Dell and Compaq) to build low cost machines to run the software. “Solution selling” was where VARs bundled what small businesses – and even many large businesses – needed by bringing together developer applications with manufacturer hardware.

It only took a few years for Microsoft to overtake Apple and IBM by dominating and growing the VAR channel. Apple did a poor job of creating a powerful developer network, preferring to develop everything users should want itself, so quickly it lacked a sufficient application base. IBM constantly tried to maintain its direct sales model (and upsell clients from PCs to more expensive hardware) rather than support the channel for developing applications or selling solutions based on PCs.

But, over the last several years Microsoft played “bet the company” on its launch of Windows 8. As mobile grew in hardware sales exponentially, and PC sales flattened (then declined,) Microsoft was tepid regarding any mobile offering. Under former CEO Steve Ballmer, Microsoft preferred creating an “all-in-one” solution via Win8 that it hoped would keep PC sales moving forward while slowly allowing its legions of Microsoft developers to build Win8 apps for mobile Surface devices — and what it further hoped would be other manufacturer’s tablets and phones running Win8.

This flopped. Horribly. Apple already had the “installed base” of users and mobile developers, working diligently to create new apps which could be released via its iTunes distribution platform. As a competitive offering, Google had several years previously launched the Android operating system, and companies such as HTC and Samsung had already begun building devices. Developers who wanted to move beyond Apple were already committed to Android. Microsoft was simply far too late to market with a Win8 product which gave developers and manufacturers little reason to invest.

Now Microsoft is in a very weak position. Despite much fanfare at launch, Microsoft was forced to take a nearly $1B write-off on its unsellable Surface devices. In an effort to gain a position in mobile, Microsoft previously bought phone maker Nokia, but it was simply far too late and without a good plan for how to change the Apple juggernaut.

Apple is now the dominant player in mobile, with the most users, developers and the most apps. Apple has upended the former Microsoft channel leadership position, as solution sellers are now offering Apple solutions to their mobile-hungry business customers. The merger with IBM brings even greater skill, and huge resources, to augmenting the base of business apps running on iOS and its devices (presently and in the future.) It provides encouragement to the VARs that a future stream of great products will be coming for them to sell to small, medium and even large businesses.

Caught in a situation of diminishing resources, after betting the company’s future on Windows 8 development and launch, and then seeing PC sales falter, Microsoft has now been forced to announce it is laying off 18,000 employees. Representing 14% of total staff, this is Microsoft’s largest reduction ever. Costs for the downsizing will be a massive loss of $1.1-$1.6B – just one year (almost to the day) after the huge Surface write-off.

Recognizing its extraordinarily weak market position, and that it’s acquisition of Nokia did little to build strength with developers while putting it at odds with manufacturers of other mobile devices, the company is taking some 12,000 jobs out of its Nokia division – ostensibly the acquisition made at a cost of $7.2B to blunt iPhone sales. Every other division is also suffering headcount reductions as Microsoft is forced to “circle the wagons” in an effort to find some way to “hold its ground” with historical business customers.

Today Apple is very strong in the developer community, already has a distribution capability with iTunes to which it is adding mobile payments, and is building a strong channel of VARs seeking mobile solutions. The IBM partnership strengthens this position, adds to Apple’s iOS developers, guarantees a string of new solutions for business customers and positions iOS as the platform of choice for VARs and VADs who will use iBeacon and other devices to help businesses become more capable by utilizing mobile/cloud technology.

Meanwhile, Microsoft is looking like the 7th Cavalry at the Little Bighorn. Microsoft is surrounded by competitors augmenting iOS and Android (and serious cloud service suppliers like Amazon,) resources are depleting as sales of “core” products stagnate and decline and write-offs mount, and watching as its “supply line” developer channel abandons Windows 8 for the competitive alternatives.

CEO Nadella keeps saying that that cloud solutions are Microsoft’s future, but how it will effectively compete at this late date is as unclear as the email announcement on layoffs Nokia’s head Stephen Elop sent to employees. Keeping its channel, long the source of market success for Microsoft, from leaving is Microsoft’s last stand. Unfortunately, Nadella’s challenge puts him in a position that looks a lot like General Custer.

by Adam Hartung | Jun 19, 2014 | Current Affairs, Disruptions, In the Swamp, Leadership, Web/Tech

Yesterday Amazon launched its new Kindle Fire smartphone.

“Ho-hum” you, and a lot of other people, said. “Why?” “What’s so great about this phone?”

The market is dominated by Apple and Samsung, to the point we no longer care about Blackberry – and have pretty much forgotten about all the money spent by Microsoft to buy Nokia and launch Windows 8. The world doesn’t much need a new smartphone maker – as we’ve seen with the lack of excitement around Google/Motorola’s product launches. And, despite some gee-whiz 3D camera and screen effects, nobody thinks Amazon has any breakthrough technology here.

But that would be completely missing the point. Amazon probably isn’t even thinking of competing heads-up with the 2 big guns in the smartphone market. Instead, Amazon’s target is everyone in retail. And they should be scared to death. As well as a lot of consumer products companies.

Amazon’s new Kindle Fire smartphone

Apple’s iPod and iPhones have some 400,000 apps. But most people don’t use over a dozen or so daily. Think about what you do on your phone:

- Talk, texting and email

- Check the weather, road conditions, traffic

- Listen to music, or watch videos

- Shopping (look for products, prices, locations, specs, availability, buy)

Now, you may do several other things. But (maybe not in priority,) these are probably the top 4 for 90% of people.

If you’re Amazon, you want people to have a great shopping experience. A GREAT experience. You’ve given folks terrific interfaces, across multiple platforms. But everything you do with an app on iPhones or Samsung phones involves negotiating with Apple or Google to be in their store – and giving them revenue. If you could bypass Apple and Google – a form of retail “middleman” in Amazon’s eyes – wouldn’t you?

Amazon has already changed retail markedly. Twenty years ago a retailer would say success relied on 2 things:

- Store location and layout. Be in the right place, and be easy to shop.

- Merchandise the goods well in the store, and have them available.

Amazon has killed both those tenets of retail. With Amazon there is no store – there is no location. There are no aisles to walk, and no shelves to stock. There is no merchandising of products on end caps, within aisles or by tagging the product for better eye appeal. And in 40%+ cases, Amazon doesn’t even stock the inventory. Availability is based upon a supplier for whom Amazon provides the storefront and interface to the customer, sending the order to the supplier for a percentage of the sale.

And, on top of this, the database at Amazon can make your life even easier, and less time consuming, than a traditional store. When you indicate you want item “A” Amazon is able to show you similar products, show you variations (such as color or size,) show you “what goes with” that product to make sure you buy everything you need, and give you different prices and delivery options.

Many retailers have spent considerably training employees to help customers in the store. But it is rare that any retail employee can offer you the insight, advice and detail of Amazon. For complex products, like electronics, Amazon can provide detail on all competitive products that no traditional store could support. For home fix-ups Amazon can provide detailed information on installation, and the suite of necessary ancillary products, that surpasses what a trained Home Depot employee often can do. And for simple products Amazon simply never runs out of stock – so no asking an aisle clerk “is there more in the back?”

And it is impossible for any brick-and-mortar retailer to match the cost structure of Amazon. No stores, no store employees, no cashiers, 50% of the inventory, 5-10x the turns, no “obsolete inventory,” no inventory loss – there is no way any retailer can match this low cost structure. Thus we see the imminent failure of Radio Shack and Sears, and the chronic decline in mall rents as stores go empty.

Some retailers have tried to catch up with Amazon offering goods on-line. But the inventory is less, and delivery is still often problematic. Meanwhile, as they struggle to become more digital these retailers are competing on ground they know precious little about. It is becoming commonplace to read about hackers stealing customer data and wreaking havoc at Michaels Stores and Target. Thus on-line customers have far more faith in Amazon, which has 2 decades of offering secure transactions and even offers cloud services secure enough to support major corporations and parts of the U.S. government.

And Amazon, so far, hasn’t even had to make a profit. It’s lofty price/earnings multiple of 500 indicates just how little “e” there is in its p/e. Amazon keeps pouring money into new ways to succeed, rather than returning money to shareholders via stock buybacks or dividends. Or dumping it into chronic store remodels, or new store construction.

Today, you could shop at Amazon from your browser on any laptop, tablet or phone. Or, if you really enjoy shopping on-line you can now obtain a new tablet or phone from Amazon which makes your experience even better. You can simply take a picture of something you want, and your new Amazon smartphone will tell you how to buy it on-line, including price and delivery. No need to leave the house. Want to see the product in full 360 degrees? You have it on your 3D phone. And all your buying experience, customer reviews, and shopping information is right at your fingertips.

Amazon is THE game changer in retail. Kindle was a seminal product that has almost killed book publishers, who clung way too long to old print-based business models. Kindle Fire took direct aim at traditional retailers, from Macy’s to Wal-Mart, in an effort to push the envelope of on-line shopping. And now the Kindle Fire smartphone puts all that shopping power in your palm, convenient with your other most commonplace uses such as messaging, fact finding, listening or viewing.

This is not a game changing smartphone in comparison with iPhone 5 or Galaxy S 5. But, as another salvo in the ongoing war for controlling the retail marketplace this is another game changer. It continues to help everyone think about how they shop today, and in the future. For anyone in retail, this may well be seen as another important step toward changing the industry forever, and making “every day low prices” an obsolete (and irrelevant) retail phrase. And for consumer goods companies this means the need to distribute products on-line will forever change the way marketing and selling is done – including who makes how much profit.

by Adam Hartung | May 30, 2014 | Current Affairs, In the Swamp, In the Whirlpool, Leadership, Sports, Web/Tech

Anyone who reads my column knows I’ve been no fan of Steve Ballmer as CEO of Microsoft. On multiple occasions I chastised him for bad decisions around investing corporate funds in products that are unlikely to succeed. I even called him the worst CEO in America. The Washington Post even had difficulty finding reputable folks to disagree with my argument.

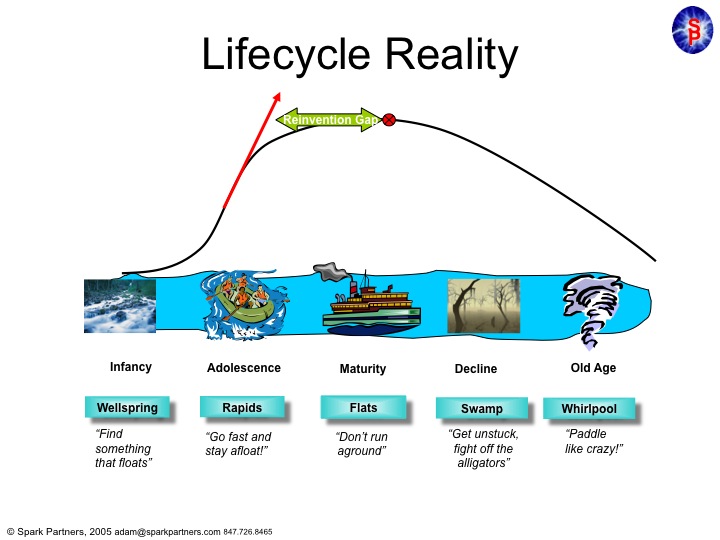

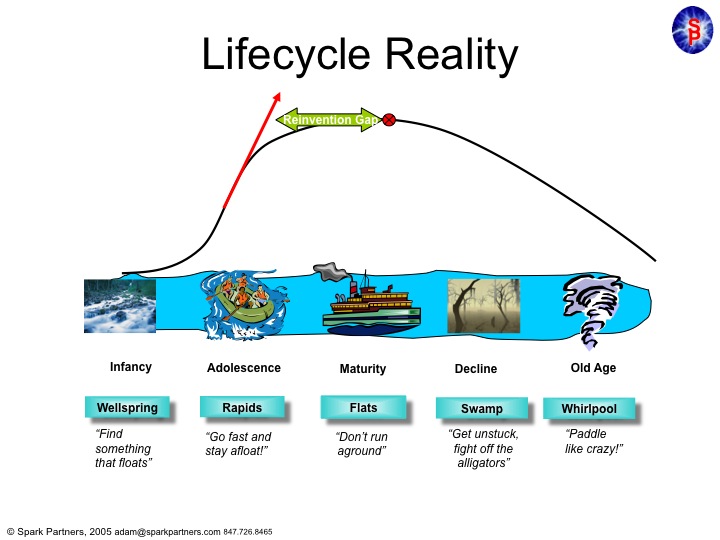

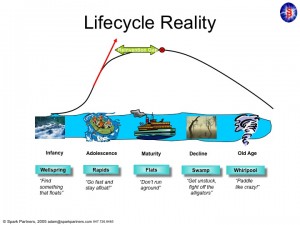

Unfortunately, Microsoft suffered under Mr. Ballmer. And Windows 8, as well as the Surface tablet, have come nowhere close to what was expected for their sales – and their ability to keep Microsoft relevant in a fast changing personal technology marketplace. In almost all regards, Mr. Ballmer was simply a terrible leader, largely because he had no understanding of business/product lifecycles.

Microsoft was founded by Bill Gates, who did a remarkable job of taking a start-up company from the Wellspring of an idea into one of the fastest growing adolescents of any American company.

Microsoft was founded by Bill Gates, who did a remarkable job of taking a start-up company from the Wellspring of an idea into one of the fastest growing adolescents of any American company.

Under Mr. Gates leadership Microsoft single-handedly overtook the original PC innovator – Apple – and left it a niche company on the edge of bankruptcy in little over a decade.

Mr. Gates kept Microsoft’s growth constantly in the double digits by not only making superior operating system software, but by pushing the company into application software which dominated the desktop (MS Office.) And when the internet came along he had the vision to be out front with Internet Explorer which crushed early innovator, and market maker, Netscape.

But then Mr. Gates turned the company over to Mr. Ballmer. And Mr. Ballmer was a leader lacking vision, or innovation. Instead of pushing Microsoft into new markets, as had Mr. Gates, he allowed the company to fixate on constant upgrades to the products which made it dominant – Windows and Office. Instead of keeping Microsoft in the Rapids of growth, he offered up a leadership designed to simply keep the company from going backward. He felt that Microsoft was a company that was “mature” and thus in need of ongoing enhancement, but not much in the way of real innovation. He trusted the market to keep growing, indefinitely, if he merely kept improving the products handed him.

As a result Microsoft stagnated. A “Reinvention Gap” developed as Vista, Windows 7, then Windows 8 and one after another Office updates did nothing to develop new customers, or new markets. Microsoft was resting on its old laurels – monopolistic control over desktop/laptop markets – without doing anything to create new markets which would keep it on the old growth trajectory of the Gates era.

Things didn’t look too bad for several years because people kept buying traditional PCs. And Ballmer famously laughed at products like Linux or Unix – and then later at entertainment devices, smart phones and tablets – as Microsoft launched, but then abandoned products like Zune, Windows CE phones and its own tablet. Ballmer kept thinking that all the market wanted was a faster, cheaper PC. Not anything really new.

And he was dead wrong. The Reinvention Gap emerged to the public when Apple came along with the iPod, iTunes, iPhone and iPad. These changed the game on Microsoft, and no longer was it good enough to simply have a better edition of an outdated technology. As PC sales began declining it was clear that Ballmer’s leadership had left the company in the Swamp, fighting off alligators and swatting at mosquitos with no strategy for how it would regain relevance against all these new competitors.

So the Board pushed him out, and demoted Gates off the Chairman’s throne. A big move, but likely too late. Fewer than 7% of companies that wander into the Swamp avoid the Whirlpool of demise. Think Univac, Wang, Lanier, DEC, Cray, Sun Microsystems (or Circuit City, Montgomery Wards, Sears.) The new CEO, Satya Nadella, has a much, much more difficult job than almost anyone thinks. Changing the trajectory of Microsoft now, after more than a decade creating the Reinvention Gap, is a task rarely accomplished. So rare we make heros of leaders who do it (Steve Jobs, Lou Gerstner, Lee Iacocca.)

So what will happen at the Clippers?

Critically, owning an NBA team is nothing like competing in the real business world. It is a closed marketplace. New competitors are not allowed, unless the current owners decide to bring in a new team. Your revenues are not just dependent upon you, but are even shared amongst the other teams. In fact your revenues aren’t even that closely tied to winning and losing. Season tickets are bought in advance, and with so many games away from home a team can do quite poorly and still generate revenue – and profit – for the owner. And this season the Indiana Pacers demonstrated that even while losing, fans will come to games. And the Philadelphia 76ers drew crowds to see if they would set a new record for the most consecutive games lost.

In America the major sports only modestly overlap, so you have a clear season to appeal to fans. And even if you don’t make it into the playoffs, you still share in the profits from games played by other teams. As a business, a team doesn’t need to win a championship to generate revenue – or make a profit. In fact, the opposite can be true as Wayne Huizenga learned owning the Championship winning Florida Marlins baseball team. He payed so much for the top players that he lost money, and ended up busting up the team and selling the franchise!

In short, owning a sports franchise doesn’t require the owner to understand lifecycles. You don’t have to understand much about business, or about business competition. You are protected from competitors, and as one of a select few in the club everyone actually works together – in a wholly uncompetitive way – to insure that everyone makes as much money as possible. You don’t even have to know anything about managing people, because you hire coaches to deal with players, and PR folks to deal with fans and media. And as said before whether or not you win games really doesn’t have much to do with how much money you make.

Most sports franchise owners are known more for their idiosyncrasies than their business acumen. They can be loud and obnoxious all they want (with very few limits.) And now that Mr. Ballmer has no investors to deal with – or for that matter vendors or cooperative parties in a complex ecosystem like personal technology – he doesn’t have to fret about understanding where markets are headed or how to compete in the future.

When it comes to acting like a person who knows little about business, but has a huge ego, fiery temper and loves to be obnoxious there is no better job than being a sports franchise owner. Mr. Ballmer should fit right in.

by Adam Hartung | May 16, 2014 | Current Affairs, Defend & Extend, In the Swamp, Leadership, Lifecycle, Web/Tech

IBM had a tough week this week. After announcing earnings on Wednesday IBM fell 2%, dragging the Dow down over 100 points. And as the Dow reversed course to end up 2% on the week, IBM continued to drag, ending down almost 3% for the week.

Of course, one bad week – even one bad earnings announcement – is no reason to dump a good company’s stock. The short term vicissitudes of short-term stock trading should not greatly influence long-term investors. But in IBM’s case, we now have 8 straight quarters of weaker revenues. And that HAS to be disconcerting. Managing earnings upward, such as the previous quarter, looks increasingly to be a short-term action, intended to overcome long-term revenues declines which portend much worse problems.

This revenue weakness roughly coincides with the tenure of CEO Virginia Rometty. And in interviews she increasingly is defending her leadership, and promising that a revenue turnaround will soon be happening. That it hasn’t, despite a raft of substantial acquisitions, indicates that the revenue growth problems are a lot deeper than she indicates.

CEO Rometty uses high-brow language to describe the growth problem, calling herself a company steward who is thinking long-term. But as the famous economist John Maynard Keynes pointed out in 1923, “in the long run we are all dead.” Today CEO Rometty takes great pride in the company’s legacy, pointing out that “Planes don’t fly, trains don’t run, banks don’t operate without much of what IBM does.”

But powerful as that legacy has been, in markets that move as fast as digital technology any company can be displaced very fast. Just ask the leadership at Sun Microsystems that once owned the telecom and enterprise markets for servers – before almost disappearing and being swallowed by Oracle in just 5 years (after losing $200B in market value.) Or ask former CEO Steve Ballmer at Microsoft, who’s delays at entering mobile have left the company struggling for relevancy as PC sales flounder and Windows 8 fails to recharge historical markets.

CEO Rometty may take pride in her earnings management. But we all know that came from large divestitures of the China business, and selling the PC and server business. As well as significant employee layoffs. All of which had short-term earnings benefits at the expense of long-term revenue growth. Literally $6B of revenues sold off just during her leadership.

Which in and of itself might be OK – if there was something to replace those lost sales. (Even if they didn’t have any profits – because at least we have faith in Amazon creating future profits as revenues zoom.)

What really worries me about IBM are two things that are public, but not discussed much behind the hoopla of earnings, acquisitions, divestitures and all the talk, talk, talk regarding a new future.

CNBC reported (again, this week,) that 121 companies in the S&P 500 (27.5%) cut R&D in the first quarter. And guess who was on the list? IBM, once an inveterate leader in R&D has been reducing R&D spending. The short-term impact? Better quarterly earnings. Long term impact????

The Washington Post reported this week about the huge sums of money pouring out of corporations into stock buybacks rather than investing in R&D, new products, new capacity, enhanced marketing, sales growth, etc. $500B in buybacks this year, 34% more than last year’s blistering buyback pace, flowed out of growth projects. To make matters worse, this isn’t just internal cash flow going for buybacks, but companies are actually borrowing money, increasing their debt levels, in order to buy their own stock!

And the Post labels as the “poster child” for this leveraged stock-propping behavior…. IBM. IBM

“in the first quarter bought back more than $8 billion of its own stock, almost all of it paid for by borrowing. By reducing the number of outstanding shares, IBM has been able to maintain its earnings per share and prop up its stock price even as sales and operating profits fall.

The result: What was once the bluest of blue-chip companies now has a debt-to-equity ratio that is the highest in its history. As Zero Hedge put it, IBM has embarked on a strategy to “postpone the day of income statement reckoning by unleashing record amounts of debt on what was once upon a time a pristine balance sheet.”

In the case of IBM, looking beyond the short-term trees at the long-term forest should give investors little faith in the CEO or the company’s future growth prospects. Much is being hidden in the morass of financial machinations surrounding acquisitions, divestitures, debt assumption and stock buybacks. Meanwhile, revenues are declining, and investments in R&D are falling. This cannot bode well for the company’s long-term investor prospects, regardless of the well scripted talking points offered last week.

by Adam Hartung | Apr 1, 2014 | Current Affairs, Defend & Extend, In the Swamp, Leadership, Web/Tech

“Hope springs eternal in the human breast” (Alexander Pope)

As it does for most investors. People do not like to accept the notion that a business will lose relevancy, and its value will fall. Especially really big companies that are household brand names. Investors, like customers, prefer to think large, established companies will continue to be around, and even do well. It makes everyone feel better to have a optimistic attitude about large, entrenched organizations.

And with such optimism investors have cheered Microsoft for the last 15 months. After a decade of trading up and down around $26/share, Microsoft stock has made a significant upward move to $41 – a new decade-long high. This price has people excited Microsoft will reach the dot.com/internet boom high of $60 in 2000.

After discovering that Windows 8, and the Surface tablet, were nowhere near reaching sales expectations after Christmas 2012 – and that PC sales were declining faster than expected – investors were cheered in 2013 to hear that CEO Steve Ballmer would resign. After much speculation, insider Satya Nadella was named CEO, and he quickly made it clear he was refocusing the company on mobile and cloud. This started the analysts, and investors, on their recent optimistic bent.

CEO Nadella has cut the price of Windows by 70% in order to keep hardware manufacturers on Windows for lower cost machines, and he announced the company’s #1 sales and profit product – Office – was being released on iOS for iPad users. Investors are happy to see this action, as they hope that it will keep PC sales humming. Or at least slow the decline in sales while keeping manufacturers (like HP) in the Microsoft Windows fold. And investors are likewise hopeful that the long awaited Office announcement will mean booming sales of Office 365 for all those Apple products in the installed base.

But, there’s a lot more needed for Microsoft to succeed than these announcements. While Microsoft is the world’s #1 software company, it is still under considerable threat and its long-term viability remains unsure.

Windows is in a tough spot. After this price decline, Microsoft will need to increase sales volume by 2.5X to recoup lost profits. Meanwhile, Chrome laptops are considerably cheaper for customers and more profitable for manufacturers. And whether this price cut will have any impact on the decline in PC sales is unclear, as users are switching to mobile products for ease-of-use reasons that go far beyond price. Microsoft has taken an action to defend and extend its installed base of manufacturers who have been threatening to move, but the impact on profits is still likely to be negative and PC sales are still going to decline.

Meanwhile, the move to offer Office on iOS is clearly another offer to defend the installed Office marketplace, and unlikely to create a lot of incremental revenue and profit growth. The PC market has long been much bigger than tablets, and almost every PC had Office installed. Shrinking at 12-14% means a lot less Windows Office is being sold. And, In tablets iOS is not 100% of the market, as Android has substantial share. Offering Office on iOS reaches a lot of potential machines, but certainly not 100% as has been the case with PCs.

Further, while there are folks who look forward to running Office on an iOS device, Office is not without competition. Both Apple and Google offer competitive products to Office, and the price is free. For price sensitive users, both individuals and corporations, after 4 years of using competitive products it is by no means a given they all are ready to pay $60-$100 per device per year. Yes, there will be Office sales Microsoft did not previously have, but whether it will be large enough to cover the declining sales of Office on the PC is far from clear. And whether current pricing is viable is far, far from certain.

While these Microsoft products are the easiest for consumers to understand, Nadella’s move to make Microsoft successful in the mobile/cloud world requires succeeding with cloud products sold to corporations and software-as-service providers. Here Microsoft is late, and facing substantial competition as well.

Just last week Google cut the price of its Compute Engine cloud infrastructure (IaaS) platform and App Engine cloud app platform (PaaS) products 30-32%. Google cut the price of its Cloud Storage and BigQuery (big data analytics) services by 68% and 85% as it competes headlong for customers with Amazon. Amazon, which has the first-mover position and large customers including the U.S. federal government, cut prices within 24 hours for its EC2 cloud computing service by 30%, and for its S3 storage service by over 50%. Amazon also reduced prices on its RDS database service approximately 28%, and its Elasticache caching service by over 33%.

To remain competitive, Microsoft had to react this week by chopping prices on its Azure cloud computing products 27%-35%, reducing cloud storage pricing 44%-65%, and whacking prices on its Windows and Linux memory-intensive computing products 27%-35%. While these products have allowed the networking division formerly run by now CEO Nadella to be profitable, it will be increasingly difficult to maintain old profit levels on existing customers, and even a tougher problem to profitably steal share from the early cloud leaders – even as the market grows.

While optimism has grown for Microsoft fans, and the share price has moved distinctly higher, it is smart to look at other market leaders who obtained investor favorability, only to quickly lose it.

Blackberry was known as RIM (Research in Motion) in June, 2007 when the iPhone was launched. RIM was the market leader, a near monopoly in smart phones, and its stock was riding high at $70. In August, 2007, on the back of its dominant status, the stock split – and moved on to a split adjusted $140 by end of 2008. But by 2010, as competition with iOS and Android took its toll RIM was back to $80 (and below.) Today the rechristened company trades for $8.

Sears was once the country’s largest and most successful retailer. By 2004 much of the luster was coming off when KMart purchased the company and took its name, trading at only $20/share. Following great enthusiasm for a new CEO (Ed Lampert) investors flocked to the stock, sure it would take advantage of historical brands such as DieHard, Kenmore and Craftsman, plus leverage its substantial real estate asset base. By 2007 the stock had risen to $180 (a 9x gain.) But competition was taking its toll on Sears, despite its great legacy, and sales/store started to decline, total sales started declining and profits turned to losses which began to stretch into 20 straight quarters of negative numbers. Meanwhile, demand for retail space declined, and prices declined, cutting the value of those historical assets. By 2009 the stock had dropped back to $40, and still trades around that value today — as some wonder if Sears can avoid bankruptcy.

Best Buy was a tremendous success in its early years, grew quickly and built a loyal customer base as the #1 retail electronics purveyor. But streaming video and music decimated CD and DVD sales. On-line retailers took a huge bite out of consumer electronic sales. By January, 2013 the stock traded at $13. A change of CEO, and promises of new formats and store revitalization propped up optimism amongst investors and by November, 2014 the stock was at $44. However, market trends – which had been in place for several years – did not change and as store sales lagged the stock dropped, today trading at only $25.

Microsoft has a great legacy. It’s products were market leaders. But the market has shifted – substantially. So far new management has only shown incremental efforts to defend its historical business with product extensions – which are up against tremendous competition that in these new markets have a tremendous lead. Microsoft so far is still losing money in on-line and gaming (xBox) where it has lost almost all its top leadership since 2014 began and has been forced to re-organize. Nadella has yet to show any new products that will create new markets in order to “turn the tide” of sales and profits that are under threat of eventual extinction by ever-more-capable mobile products.

While optimism springs eternal long-term investors would be smart to be skeptical about this recent improvement in the stock price. Things could easily go from mediocre to worse in these extremely competitive global tech markets, leaving Microsoft optimists with broken dreams, broken hearts and broken portfolios.

Update: On April 2 Microsoft announced it is providing Windows for free to all manufacturers with a 9″ or smaller display. This is an action to help keep Microsoft competitive in the mobile marketplace – but it does little for Microsoft profitability. Android from Google may be free, but Google’s business is built on ad sales – not software sales – and that’s dramatically different from Microsoft that relies almost entirely on Windows and Office for its profitability

Update: April 3 CRN (Computer Reseller News) reviewed Office products for iOS – “We predict that once the novelty of “Office for iPad” wears off, companies will go back to relying on the humble, hard-working third parties building apps that are as stable, as handsome and far more capable than those of Redmond. It’s not that hard to do.”

by Adam Hartung | Mar 25, 2014 | Current Affairs, Ethics, Leadership, Web/Tech

5:00pm, September 20, 2009 was when I got the call.

Someone’s telling me to call the Wisconsin Highway Patrol, my oldest son was in a terrible accident. Then I call the police, who tell me my son has been airlifted to a hospital. I’m in the car, madly driving 500 miles toward the hospital, talking to the doctor – hearing my son is in bad shape. It looks terminal. Continuing the drive, deep into the blackest night, in the pouring rain.

Then the call from the hospital. My son was dead.

I kept up the drive, made it to the hospital at daybreak. Yes, that is my son. Yes, he is dead.

I guess I had to see it to believe it.

Suddenly a new realization hit me. My son has two brothers. Both in college. Both 500 miles away. They had no idea what my last 14 hours were like. They knew nothing about their brother. How would they learn about this horrific news?

This accident was not a secret. It was newsworthy, even if far from a major city. My dead son had dozens of friends. And they all use Facebook. While as young men my sons don’t pay much attention to news radio or TV, they do pay attention to Facebook. And texting. How long would it take before someone went on-line and started telling the world that their brother was dead?

Do you call your sons on the phone and tell them their brother died?

Not wasting any time, I jumped in the car and started straight for my middle son’s college. He was the closest with his brother. They exchanged texts every day. He would be checking his phone and his Facebook account. I made the decision that this – this one thing – this had to be done in person. I would not call, I would not text, I was going to tell him in person.

But could I beat Facebook and texting?

I loaded up with coffee and went back onto the highway. And started another 10 hour drive. I just kept wondering “how long do I have? How long before these boys find the out – the hard way?”

I called my neighbor and told her the news. I gave her my Facebook access and told her to monitor my account, and to pay attention to any traffic from people in my son’s network. Look for anything that even hinted of bad news. I had to focus on driving and couldn’t distract myself with mobile.

Eight hours later I drove into Chicago. I was between 30 and 90 minutes to my son. Depending on Chicago traffic! But things seemed light; lighter than normal. Maybe, just maybe, I had time.

As I pulled across town I knew I was only 20 minutes from my middle son. Then my phone rang. It was my neighbor. “It’s there Adam. It’s there on Facebook. Somebody found out, and the kids are starting to spread the news. You better hurry.”

As safely, yet quickly, as possible I navigated in front of his 3 flat apartment on the south side. Luckily, a parking spot on the street. I pulled in, jumped out of the car and saw a window open in his apartment. I started calling up “hey, you up there? I need you to come unlock the door. Hey, come to the door.”

Laconically my son came to the door. I could tell by his eyes he didn’t know anything, and was curious why I was there. I went inside, put my arms around him, and told him his brother was dead.

He accused me of a bad joke. I quickly told him an accident happened, where, and that his brother didn’t make it.

Of course, he did not believe me. So he picked up his phone. He started looking for texts. He saw there were none from his brother. Then he jumped to his PC. He pulled up Facebook. He looked for his brother’s page – and then he started seeing the messages. Messages of disbelief, grief, anger and fear as expressed by so many people who are 21 or 22 and suddenly come face to face with mortality.

My son was in shock, as could be expected. But he was with me. Then it hit him “have you told my little brother?” I told him no. “We have to go tell him. Now. Before he finds out some other way.”

We then jumped back in the car and beat it to his younger brother’s college. My youngest son was far less of a social media fan. Also, college soccer kept him very busy. We knew he had been in class and soccer practice most of the day and evening, and he would not check anything until late at night. We had a very good chance that he had not heard anything.

Luckily, when we arrived at his college and found him, he confirmed he had not seen his phone or PC for several hours while at class, practice, eating and finishing homework. We told him the very, very bad news.

I’m glad my sons did not hear of their brother’s death via a text. Or via Facebook. It was a very, very, very difficult day for us. And the next several. Every minute etched forever in our memories.

As the next few days passed we all gained huge comfort from those who reached out to us via text, Facebook and Tweets. Hundreds of messages and postings came in. Social media was a tremendous way for all of us to connect and share stories about my now lost son. Young people told me things I would never have known had they been limited to telling me face-to-face, but which they were willing to share via Facebook. It was incredibly helpful.

We live in a very, very connected world.

Information, even things which may seem obscure in this large global environment, find their way to light quickly. We all want information now – not later. We want to know what, where and when – and we want to know it now. We sign up for email newsletters, Facebook pages, linked-in networks and listen to our colleagues on Twitter so we know things as soon as possible.

This is tough for those who have to communicate bad news. What’s the trade-off? Do you wait and do it personally? Or do you opt for moving quickly? Is it better someone know the information now – even if it is painful – or do you seek to inform them in a personal way to address their needs, emotions and questions? Do you broadcast the news, or keep it small? Do you send it impersonally, or personally? What is important?

Every organization is, to some extent, in the trust business

When you have to deliver bad news, how will you do it? Whether you have to announce a layoff, plant closing, industrial accident, data breach, product recall, product failure, program failure – or even a fatality – you are communicating information that is personal, and emotional. It is information that requires a sense of the person, not just the news. How will the information be received – and what does that mean for how it should be communicated?

It takes continuous effort to build trust, but it can be lost in a single, poorly constructed communication.

Malaysia Airlines had years to plan its communications for a downed plane. How would it tell the world such news? What tools would it use? A preparedness plan should contain not only the action plan, but the communications plan as well. And not only the message, but how it will be delivered. And how all touch points between the organization and the audience will be addressed.

Once flight 370 went missing Malaysia Airlines had days to plan its communications with families. There were several possible scenarios, yet all had a common theme of communicating passenger status. Passengers that are family members. The airline had significant time to plan what it would say, and how. To settle on texting families that their loved ones were forever gone was either incredibly bad planning, or indicates a significant lack of planning communications altogether.

When it was time for my sons to learn their brother was dead someone needed to be there to support them. Someone who cared. It was not news to be internalized without more discussion about what, how and why. All bad news shares this requirement, to address the human need to ask questions. Relying on email, texting, social media, newsletters or broadcast to share bad news ignores the very personal impact bad news has on the recipients.

Nobody wants to deliver bad news, but sometimes it is unavoidable. Being prepared is incredibly important if you want to maintain trust. Otherwise you can look as heartless, and untrustworthy, as Malaysia Airlines.

Connect with me on LinkedIn, Facebook and Twitter.

by Adam Hartung | Feb 24, 2014 | Current Affairs, Defend & Extend, In the Rapids, Leadership, Transparency, Web/Tech

Facebook is acquiring WhatsApp, a company with at most $300M revenues, and 55 employees, for $19billion. That’s billion – with a “b.” An astonishing figure that is second only to HP’s acquisition of market leader Compaq, which had substantial revenues and profits, as tech acquisitions. $19B is 13 times Facebook’s (not WhatsApp’s) entire 2013 net income – and almost 2.5 times Facebook’s (again, not WhatsApp’s) 2013 gross revenues!

On the mere face of it this valuation should make the most dispassionate analyst swoon. In today’s world very established, successful companies sell for far, far lower valuations. Apple is valued at about 13 times earnings. Microsoft about 14 times earnings. Google 33 times. These are small fractions of the nearly infinite P/E placed on WhatsApp.

But there is a leadership lesson offered here by CEO Zuckerberg’s team that is well worth learning.

Irrelevancy can happen remarkably quickly. True in any industry, but especially in digital technology. Examples: Research-in-Motion/Blackberry. Motorola. Dell. HP all lost relevancy in months and are struggling. (For those who want non-tech examples think of Circuit City, Best Buy, Sears, JCPenney, Abercrombie and Fitch.) Each of these companies was an industry leader that lust its luster, most of its customers, a big chunk of its employees and much of its market valuation in months when the company missed a market shift.

Although leadership knew what it had historically done to sell products profitably, in a very short time market trends reduced the value of the company’s historical success formula leaving investors, as well as management, wondering how it was going to compete.

Facebook is not immune to changing market trends. Although it has been the benchmark for social media, it only achieved that goal after annihilating early leader MySpace. And although Facebook was built by youthful folks, trends away from using laptops and toward mobile devices have challenged the Facebook platform. Simultaneously, changing communication requirements have altered the use, and impact, of things like images, photos, charts and text. All of these have the potential impact of slowly (or not so slowly) eroding the value (which is noticably lofty) of Facebook.

Most leaders address these kinds of challenges by launching new products to leverage the trend. And Facebook did just that. Facebook not only worked on making the platform more mobile friendly, but developed its own platform apps for photos and texting and all kinds of new features.

But, and this is critical, external companies did a better job. Two years ago Instagram emerged as a leader in image sharing. And WhatsApp has developed a superior answer for messaging.

Historically leadership usually said “we need to find a way to beat these new guys.” They would make it hard to integrate new solutions with their dominant platform in an effort to block growth. They would spend huge amounts on marketing and branding to try overcoming the emerging leader. Often they filed intellectual property litigation in an effort to cause short-term business interuption and threaten viability. They might even try hiring the emerging company’s tech leader away to stop development.

All of these actions were efforts to defend & extend the early leader’s market position. Even though the market is shifting, and trends are developing externally from the company, leadership will tend to look inside for an answer. It will often ignore the trend, disparage the competition, keep promising improvements to its historical products and services and blanket the media with PR as to its stated superiority.

But, as that list (above) of companies that lost relevancy demonstrates, this rarely works. In a highly interconnected, fast-paced, globally competitive marketplace customers go where they want. Quickly. Often leaving the early leader with a management team (and Board of Directors) scratching its head and wondering how it lost so much market position, and value, so quickly.

Hand it to Mr. Zuckerberg’s team. Instead of ignoring trends in its effort to defend & extend its early lead, they reached out and brought the leader to them. $1B for Instagram was a big investment, especially so close to launching an IPO. But, it kept Facebook relevant in mobile platforms and imaging.

And making a nosebleed-creating $19B deal for WhatsApp focuses on maintaining relevancy as well. WhatsApp already processes almost as many messages as the entire telecom industry. It has 450million users with 70% active daily, which is already 60% the size of Facebook’s daily user community (550million.) By bringing these people into the Facebook corporate family it assures the company of continued relevancy as the market shifts. It doesn’t matter if these are the same people, or different people. The issue is that it keeps Facebook relevant, rather than losing relevance to a competitor.

How will this all be monetized into $19B? The second brilliant leadership call by Facebook is to not answer that question.

Facebook didn’t know how to monetize its early leadership in users, but management knew it had to find a way. Now the company has grown from almost no revenues in 2008 to almost $8B in just 5 years. (Does your company have a plan to add $8B/year of organic revenue growth by 2019?)

So just as Facebook had to find its revenue model (which it is still exploring,) Zuckerberg’s team allows the leadership of Instagram and WhatsApp to remain independent, operating in their own White Space, to grow their user base and learn how to monetize what is an extraordinarily large group of happy folks. When looking to grow in new markets, and you find a team with the skills to understand the trends, it is independence rather than integration that makes the most sense organizationally.

Thirdly, back to that valuation issue. $19B is a huge amount of money. Unless you don’t really spend $19B. Facebook has the blessed ability to print its own. Private money that it can use for such acquisitions. As long as Facebook has a very high market valuation it can make acquisitions with shares, rather than real money.

In the case of both Instagram and WhatsApp the acquisition is being made in a mix of cash, Facebook stock and restricted Facebook stock for employees. The latter two of these three items are not real money. They are simply pieces of paper giving claims to ownership of Facebook, which itself is valued at 22 times 2013 revenue and 116 times 2013 earnings. The price of those shares are all based on expectations; expectations which now require the performance of Instagram and WhatsApp to make happen.

By making acquisitions with Facebook shares the leadership team is able to link the newly acquired managers to the same overall goals as Facebook, while offering an extremely high price but without actually having to raise any money – or spend all that money.

All companies risk of becoming irrelevant. New technologies, customer behavior patterns, regulations, inventions and innovations constantly challenge old success formulas. Most leaders fall into a pattern of trying to defend & extend their old business in the face of market shifts, hastening the fall into irrelevancy. Or they try to acquire a new business, then integrate it into the old business which strips away the new business value and leads, inevitably, to irrelevancy.

The leaders of Facebook are giving us a lesson in an alternative approach. (1) Recognize the market shift. Accept it. If there is a better solution, rush toward it rather than ignoring it. (2) Bring it into the company, and leave it independent. Eschew integration and efforts to find “synergy.” (You never know, in 3 years the company may need to be renamed WhatsApp to reflect a new market paradigm.) (3) And as long as you can convince investors that you are maintaining your relevancy use your highly valued stock as currency to keep the company moving forward.

These are 3 great lessons for all leadership teams. And I continue to think Facebook is the one stock to own in 2014.