by Adam Hartung | Mar 9, 2015 | Current Affairs, Defend & Extend, In the Whirlpool, Leadership

Best Buy, the venerable electronics retailer, is hitting 52 week highs. Coming off a low of $24 in April, 2014 the current price of about $40 is a 67% increase in just 10 months. Analysts are now cheering investors to own the stock, with Marketwatch pronouncing that the last bearish analyst has thrown in the towel.

If you are a trader, perhaps you want to consider this stock. But if you aren’t an investment professional, and you buy and hold stocks for years, then Best Buy is not a stock you should own.

The bullish case for owning Best Buy is based on recovering sales per store, and recovering earnings, after a reduction in the number of stores, and employees, lowered costs. Further, with Radio Shack now in bankruptcy sales are showing an uptick as customers swing over. And that is expected to continue as Sears closes more stores on its marches toward bankruptcy. Additionally, it is hoped that lower gasoline prices will allow consumers to spend more on electronics and appliances at Best Buy.

But, this completely ignores the trend toward on-line retail sales, and the long-term deleterious impact this trend will have on Best Buy. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, on-line sales as a percent of all retail have grown from less than 2.4% in 2005 to over 7.6% by end of 2014 – more than tripling! But more critical to this discussion, all retail sales includes automobiles, lumber, groceries – lots of things where there is little or no online volume.

As most folks know, the number one category for online sales is computers and consumer electronics, which consistently accounts for about 20% of ALL online retail. In fact, about 25% of all consumer electronics are sold online. So the growth in online retail is disproportionately in the Best Buy wheelhouse. The segment where Best Buy competes against streamlined online retailers such as NewEgg.com, ThinkGeek.com and the ever-dominant Amazon.com.

So while in the short term some traditional retail customers will now shift demand to Best Buy, this is not unlike the revenue “bounce” Best Buy received when Circuit City failed. Short term up, but the long term trend continued hammering away at Best Buy’s core market.

This is a big deal because the marginal economic impact of this shift is horrific to Best Buy. In traditional retail most costs are “fixed,” meaning they can’t be changed much month to month. The cost of real estate, store maintenance, utilities and staff cannot be easily adjusted – unless there is a decision to close a gob of stores. Thus losing even a few sales, what economists call “marginal” sales, wreaks havoc on earnings.

Back in 2010 and 2011 Best Buy made a net income (’12 and ’13 were losses) of about 2.6% – or about $2.60 on every $100 revenue. Cost of Goods sold is about 75% of revenue. So on $100 of revenue, $25 is available to cover fixed costs. If revenue falls by just $10, Best Buy loses $2.50 of margin to cover fixed costs. Remember, however, that the net income is only $2.60. So losing 10% of revenue ($10 out of the $100) means Best Buy loses $2.50 of contribution to fixed costs, and that is deducted from net income of $2.60, leaving Best Buy with a meager 10cents of profitability. A 10% loss of revenue wipes out 96% of profits!

Now you know why retailers who lose even a small part of their sales are suddenly closing stores right and left.

Looking forward, online retail sales are forecast to grow by another 57%, reaching 11% of total retail by 2018. But, as we know, this is disproportionately going to be driven by consumer electronics. Which means that while sales for Best Buy stores are up short term, long term they will plummet. That means there will be more store closings, and layoffs as sales shrink. And, increasingly Best Buy will have to compete head-to-head online against entrenched, leading competitors who have been stealing market share for 10+ years.

If you want to trade on the short-term uptick in revenue, and return to slight profitability, then hold your breath and see if you can outsmart the market by picking the right time, and price, for buying and selling Best Buy. But, if you like to invest in strong companies you expect to grow for another 5 years without having to be a market timer, then avoid Best Buy.

Quite simply, it is never a good idea to bet against a long term trend. Short term aberrations will happen, and it may look like the trend has changed. But the trend to online commerce is picking up steam, not reducing. If you want to invest in retail, you want to invest in those companies that demonstrate they can capture the customer’s revenue in the growing, online marketplace.

by Adam Hartung | Feb 12, 2015 | Current Affairs, Disruptions, Innovation, Leadership, Web/Tech

Despite huge fanfare at launch, after a few brief months Google Glass is no longer on the market. The Amazon Fire Phone was also launched to great hype, yet sales flopped and the company recently took a $170M write off on inventory.

Fortune mercilessly blamed Fire Phone’s failure on CEO Jeff Bezos. The magazine blamed him for micromanaging the design while overspending on development, manufacturing and marketing. To Fortune the product was fatally flawed, and had no chance of success according to the article.

Similarly, the New York Times blasted Google co-founder and company leader Sergie Brin for the failure of Glass. He was held responsible for over-exposing the product at launch while not listening to his own design team.

Both these articles make the common mistake of blaming failed new products on (1) the product itself, and (2) some high level leader that was a complete dunce. In these stories, like many others of failed products, a leader that had demonstrated keen insight, and was credited with brilliant work and decision-making, simply “went stupid” and blew it. Really?

Unfortunately there are a lot of new products that fail. Such simplistic explanations do not help business leaders avoid a future product flop. But there are common lessons to these stories from which innovators, and marketers, can learn in order to do better in the future. Especially when the new products are marketplace disrupters; or as they are often called, “game changers.”

Do you remember Segway? The two wheeled transportation device came on the market with incredible fanfare in 2002. It was heralded as a game changer in how we all would mobilize. Founders predicted sales would explode to 10,000 units per week, and the company would reach $1B in sales faster than ever in history. But that didn’t happen. Instead the company sold less than 10,000 units in its first 2 years, and less than 24,000 units in its first 4 years. What was initially a “really, really cool product” ended up a dud.

There were a lot of companies that experimented with Segways. The U.S. Postal Service tested Segways for letter carriers. Police tested using them in Chicago, Philadelphia and D.C., gas companies tested them for Pennsylvania meter readers, and Chicago’s fire department tested them for paramedics in congested city center. But none of these led to major sales. Segway became relegated to niche (like urban sightseeing) and absurd (like Segway polo) uses.

Segway tried to be a general purpose product. But no disruptive product ever succeeds with that sort of marketing. As famed innovation guru Clayton Christensen tells everyone, when you launch a new product you have to find a set of unmet needs, and position the new product to fulfill that unmet need better than anything else. You must have a very clear focus on the product’s initial use, and work extremely hard to make sure the product does the necessary job brilliantly to fulfill the unmet need.

Nobody inherently needed a Segway. Everyone was getting around by foot, bicycle, motorcycle and car just fine. Segway failed because it did not focus on any one application, and develop that market as it enhanced and improved the product. Selling 100 Segways to 20 different uses was an inherently bad decision. What Segway needed to do was sell 100 units to a single, or at most 2, applications.

Segway leadership should have studied the needs deeply, and focused all aspects of the product, distribution, promotion, training, communications and pricing for that single (or 2) markets. By winning over users in the initial market Segway could have made those initial users very loyal, outspoken customers who would recommend the product again and again – even at a $4,000 price.

Segway should have pioneered an initial application market that could grow. Only after that could Segway turn to a second market. The first market could have been using Segway as a golfer’s cart, or as a walking assist for the elderly/infirm, or as a transport device for meter readers. If Segway had really focused on one initial market, developed for those needs, and won that market it would have started a step-wise program toward more applications and success. By thinking the general market would figure out how to use its product, and someone else would develop applications for specific market needs, Segway’s leaders missed the opportunity to truly disrupt one market and start the path toward wider success.

The Fire Phone had a great opportunity to grow which it missed. The Fire Phone had several features making it great for on-line shopping. But the launch team did not focus, focus, focus on this application. They did not keep developing apps, databases and ways of using the product for retailing so that avid shoppers found the Fire Phone superior for their needs. Instead the Fire Phone was launched as a mass-market device. Its retail attributes were largely lost in comparisons with other general purpose smartphones.

The Fire Phone had a great opportunity to grow which it missed. The Fire Phone had several features making it great for on-line shopping. But the launch team did not focus, focus, focus on this application. They did not keep developing apps, databases and ways of using the product for retailing so that avid shoppers found the Fire Phone superior for their needs. Instead the Fire Phone was launched as a mass-market device. Its retail attributes were largely lost in comparisons with other general purpose smartphones.

People already had Apple iPhones, Samsung Galaxy phones and Google Nexus phones. Simultaneously, Microsoft was pushing for new customers to use Nokia and HTC Windows phones. There were plenty of smartphones on the market. Another smartphone wasn’t needed – unless it fulfilled the unmet needs of some select market so well that those specific users would say “if you do …. and you need…. then you MUST have a FirePhone.” By not focusing like a laser on some specific application – some specific set of unmet needs – the “cool” features of the Fire Phone simply weren’t very valuable and the product was easy for people to pass by. Which almost everyone did, waiting for the iPhone 6 launch.

This was the same problem launching Google Glass. Glass really caught the imagination of many tech reviewers. Everyone I knew who put on Glass said it was really cool. But there wasn’t any one thing Glass did so well that large numbers of folks said “I have to have Glass.” There wasn’t any need that Glass fulfilled so well that a segment bought Glass, used it and became religious about wearing Glass all the time. And Google didn’t improve the product in specific ways for a single market application so that users from that market would be attracted to buy Glass. In the end, by trying to be a “cool tool” for everyone Glass ended up being something nobody really needed. Exactly like Segway.

Microsoft recently launched its Hololens. Again, a pretty cool gadget. But, exactly what is the target market for Hololens? If Microsoft proceeds down the road of “a cool tool that will redefine computing,” Hololens will likely end up with the same fate as Glass, Segway and Fire Phone. Hololens marketing and development teams have to find the ONE application (maybe 2) that will drive initial sales, cater to that application with enhancements and improvements to meet those specific needs, and create an initial loyal user base. Only after that can Hololens build future applications and markets to grow sales (perhaps explosively) and push Microsoft into a market leading position.

Microsoft recently launched its Hololens. Again, a pretty cool gadget. But, exactly what is the target market for Hololens? If Microsoft proceeds down the road of “a cool tool that will redefine computing,” Hololens will likely end up with the same fate as Glass, Segway and Fire Phone. Hololens marketing and development teams have to find the ONE application (maybe 2) that will drive initial sales, cater to that application with enhancements and improvements to meet those specific needs, and create an initial loyal user base. Only after that can Hololens build future applications and markets to grow sales (perhaps explosively) and push Microsoft into a market leading position.

All companies have opportunities to innovate and disrupt their markets. Most fail at this. Most innovations are thrown at customers hoping they will buy, and then simply dropped when sales don’t meet expectations. Most leaders forget that customers already have a way of getting their jobs done, so they aren’t running around asking for a new innovation. For an innovation to succeed launchers must identify the unmet needs of an application, and then dedicate their innovation to meeting those unmet needs. By building a base of customers (one at a time) upon which to grow the innovation’s sales you can position both the new product and the company as market leaders.

by Adam Hartung | Jan 22, 2015 | Current Affairs, Defend & Extend, Games, In the Swamp, Innovation, Leadership, Software, Web/Tech

Yesterday Microsoft conducted a pre-launch of Windows 10, demonstrating its features in an effort to excite developers and create some buzz before consumer launch later in 2015.

By and large, nobody cared. Were you aware of the event? Did you try to watch the live stream, offered via the Microsoft web site? Were you eager to read what people thought of the product? Did you look for reviews in the Wall Street Journal, USA Today and other general news outlets?

Microsoft really blew it with Windows 8 – which is the second most maligned Windows product ever, exceeded only by

Vista. But that wasn’t hard to predict, in June, 2012. Even then it was clear that Windows 8, and Surface tablets, were designed to defend and extend the installed Windows base, and as such the design precluded the opportunity to change the market and pull mobile users to Microsoft.

And, unfortunately, that is how Windows 10 has been developed. At the event’s start Microsoft played a tape driving home how it interviewed dozens and dozens of loyal Windows customers, asking them what they didn’t like about 8, and what they wanted in a Windows upgrade. That set the tone for the new product.

Microsoft didn’t seek out what would convert all those mobile users already on iOS or Android to throw away their devices and buy a Microsoft product. Microsoft didn’t ask its defected customers what it would take to bring them back, nor did it ask the over 50% of the market using Windows 7 or older products what it would take to get them to go to Windows mobile rather than an iPad or Galaxy tablet. Nope. Microsoft went to its installed base and asked them what they would like.

Imagine it’s 1975 and for two decades you have successfully made and sold small offset printing presses. Every single company of any size has one in their basement. But customers have started buying really simple, easy to use Xerox machines. Fewer admins are sending even fewer jobs to the print shop in the basement, as they choose to simply run off a bunch of copies on the Xerox machine. Of course these copies are more expensive than the print shop, and the quality isn’t as good, but the users find the new Xerox machines good enough, and they are simple and convenient.

What are you to do if you make printing presses? You probably need to find out how you can get into a new product that actually appeals to the users who no longer use the print shop. But, instead, those companies went to the print shop operators and asked them what they wanted in a new, small print machine. And then the companies upgraded their presses and other traditional printing products based upon what that installed base recommended. And it wasn’t long before their share of printing eroded to a niche of high-volume, and often color, jobs. And the commercial print market went to Xerox.

That’s what Microsoft did with Windows 10. It asked its installed base what it wanted in an operating system. When the problem isn’t the installed base, its the substitute product that is killing the company. Microsoft didn’t need input from its installed base of loyal users, it needed input from people who have quit using HP laptops in favor of iPads.

There are a lot of great new features in Windows 10. But it really doesn’t matter.

The well spoken presenters from Microsoft laid out how Windows 10 would be great for anyone who wants to go to an entirely committed Windows environment. To achieve Microsoft’s vision of the future every one of us will throw away our iOS and Android products and go to Windows on every single device. Really. There wasn’t one demonstration of how Windows would integrate with anything other than Windows. And there appeared on intention of making the future an interoperable environment. Microsoft’s view was we would use Windows on EVERYTHING.

Microsoft’s insular view is that all of us have been craving a way to put Windows on all our devices. We’ve been sitting around using our laptops (or desktops) and saying “I can’t wait for Microsoft to come out with a solution so I can throw away my iPhone and iPad. I can’t wait to tell everyone in my organization that now, finally, we have an operating system that IT likes so much that we want everyone in the company to get rid of all other technologies and use Windows on their tablets and phones – because then they can integrate with the laptops (that most of us don’t use hardly at all any longer.)”

Microsoft even went out of its way to demonstrate how well Win10 works on 2-in-1 devices, which are supposed to be both a tablet and a laptop. But, these “hybrid” devices really don’t make any sense. Why would you want something that is both a laptop and a tablet? Who wants a hybrid car when you can have a Tesla? Who wants a vehicle that is both a pick-up and a car (once called the El Camino?) Microsoft thinks these are good devices, because Microsoft can’t accept that most of us already quit using our laptop and are happy enough with a tablet (or smartphone) alone!

Microsoft presenters repeatedly reminded us that Windows is evolving. Which completely ignores the fact that the market has been disrupted. It has moved from laptops to mobile devices. Yes, Windows has a huge installed base on machines that we use less and less. But Windows 10 pretends that there does not exist today an equally huge, and far more relevant, installed base of mobile devices that already has millions of apps people use every single day over and over. Microsoft pretended as if there is no world other than Windows, and that a more robuts Windows is something people can’t wait to use! We all can’t wait to go back to a exclusive Microsoft world, using Windows, Office, the new Spartan browser – and creating documents, spreadsheets and even presentations using Office, with those hundreds of complex features (anyone know how to make a pivot table?) on our phones!

Just like those printing press manufacturers were sure people really wanted documents printed on presses, and couldn’t wait to unplug those Xerox machines and return to the old way of doing things. They just needed presses to have more features, more capabilities, more speed!

The best thing in Windows 10 is Cortana, which is a really cool, intelligent digital assistant. But, rather than making Cortana a tool developers can buy to integrate into their iOS or Android app the only way a developer can use Cortana is if they go into this exclusive Windows-only world. That’s a significant request.

Microsoft made this mistake before. Kinect was a great tool. But the only way to use it, initially, was on an xBox – and still is limited to Windows. Despite its many superb features, Kinect didn’t develop anywhere near its potential. Cortana now suffers from the same problem. Rather than offering the tool so it can find its best use and markets, Microsoft requires developers and consumers buy into the Windows-exclusive world if you want to use Cortana.

Microsoft hasn’t yet figured out that it lost relevance years ago when it missed the move to mobile, and then launched Windows 8 and Surface to markets that didn’t really want those products. Now the market has gone mobile, and the leader isn’t Microsoft. Microsoft has to find a way to be relevant to the millions of people using alternative products, and the Windows 10 vision, which excludes all those competing devices, simply isn’t it.

There was lots of neat geeky stuff shown. Surface tablets using Windows 10 with an xBox app can now do real gaming, which looks pretty cool and helps move Microsoft forward in mobile gaming. That may be a product that sets Sony’s Playstation and Nintendo’s Wii on their heels. But that’s gaming, and historically not where Microsoft makes any money (nor for that matter does Sony or Nintendo.)

There is a new interactive whiteboard that integrates Skype and Windows tablets for digital enhancement of brainstorming meetings. But it is unclear how a company uses it when most employees already have iPhones or Samsung S5s or Notes. And for the totally geeky there was a demo of a holographic headset. But when it comes to disruptive products like this success requires finding really interesting applications that otherwise cannot be completed, and then the initial customers who have a really desperate need for that application who will become devoted users.

Launching such disruptive products has long been the bane of Microsoft’s existence. Microsoft thinks in mass market terms, and selling to its base. Not developing breakthrough applications and finding niche markets to launch new uses. Nor has Microsoft created a developer community aligned with that kind of work. They have long been taught to simply continue to do things that defend and extend the traditional base of product uses and customers.

The really big miss for this meeting was understanding developer needs. Today developers have an enormous base of iOS and Android users to whom they can sell their products. Windows has less than 3% share in mobile devices. What developer would commit their resources to developing products for Windows 10, which has an installed base only in laptops and desktops? In other words, yesterday’s technology base? Especially when to obtain the biggest benefits of Windows 10 that developer has to find end use customers (companies or consumers) willing to commit 100% to Windows everywhere – even including their televisions, thermostats and other devices in our ever smarter buildings?

Windows 10 has a lot of cool features. But Microsoft made a big miss by listening to the wrong people. By assuming its installed base couldn’t wait for a Microsoft-exclusive solution, and by behaving as if the installed base of mobile devices either didn’t exist or didn’t matter, the company showed its hubris (once again.) If all it took to succeed were great products, the market would never have shifted from Macintosh computers to Windows machines in the 1990s. Microsoft simply doesn’t realize that it lacks the relevance to pull of its grand vision, and as such Windows 10 has almost no chance of stopping the Apple/Google/Samsung juggernaut.

by Adam Hartung | Dec 24, 2014 | Defend & Extend, Disruptions

The Twelve Days of Christmas refers to an ancient festive season which begins on December 25. Colonial Americans modified this a bit by creating wreaths which they hung on neighbors’ doors on December 24 in anticipation of starting the festival of twelve days, which historically included feasts and celebrations.

Better known is the song “The Twelve Days of Christmas” which is believed to have started as a French folk rhyme, then later published in 1780 England. The song commemorates the twelve days of Christmas by offering ever grander gifts on each day of the holiday season.

So, it being Christmas Eve I am stealing this idea completely and offering my list of the 12 gifts investors would like to receive this holiday season from the companies into which they invest:

- Stop waxing eloquently about what you did last year or quarter. Yesterday has come and gone. Tell me about the future.

- Tell me about important trends that are going to impact your business. Is it demographics, aging population, the ecology movement, digitization, regulatory change, organic foods, mobility, mobile payments, nanotech, biotech… ? What are the critical trends that will impact your business going forward?

- Tell me your future scenarios. How will these trends change the way your customers and your company will behave? What are your most likely scenarios (and don’t try to be creative in an effort to preserve the status quo!)

- Tell me how the game will change for your industry over the next 1, 3, and 5 years. How will things be different for the industry, based on the trends and scenarios. The world is a fast changing place, and I want to know how this will change your industry.

- Tell me about the customers you lost last year. I gain no value from hearing about, or from, your favorite customers that love what currently do. Instead, bring me info on the customers who are buying alternative products, changing their behaviors, in ways that might impact sales. Even if these changes are only a small percentage of revenue.

- Tell me who the competitors are that are trying to change the game. Don’t tell me that these companies will fail. Tell me who the folks are that are really trying to do something new and different.

- Tell me about the fringe competitors. The ones you constantly say do not matter because they are small, or not part of the historical industry, or from some distant location where you don’t now compete. Tell me about the companies doing the new things which are seen as remote and immaterial, but are nibbling at the edges of the market.

- Tell me how you are reacting to potential game changers in your market. What are your plans to deal with disruptive competitors and disruptive innovations affecting your way of doing business? Other than working harder, faster, cheaper and planning to do better, what are you planning to do differently?

- Tell me how you intend to be a market game changer. Tell me what you intend to do that aligns with trends and leads the company toward fulfilling future scenarios as a market leader.

- Tell me what projects you are undertaking to experiment with new forms of competition, attracting new customers and creating new markets. Tell me about your teams that are working in white space to discover new opportunities.

- Tell me how you will disrupt your own organization so the constant effort to enhance the old success formula doesn’t kill any effort to do something new and different. How will you keep these experimental white space teams from being killed, or simply starved of resources, by the organizational inertia to defend and extend the status quo.

- Tell me the goals of these project teams, and how they will be nurtured and supplemented, as well as evaluated, to lead the company in new directions. Don’t just tell me that you will measure sales or profits, but rather real goals that measure market learning and ability to understand new customer behaviors.

If investors had this transparency, rather than merely reams and reams of historical data, just imagine how much smarter we could all invest.

Happy Holidays!

by Adam Hartung | Dec 18, 2014 | Current Affairs, Defend & Extend, Food and Drink, Leadership, Lifecycle

It is that time of year when many of us celebrate with an alcoholic beverage. But increasingly in America, that beverage is not beer. Since 2008, American beer sales have fallen about 4%.

But that decline has not been equally applied to all brands. The biggest, old line brands have suffered terribly. Nearly gone are old brands like Milwaukee’s Best, which were best known for being low priced – and certainly not focused on taste. But the most hurt, based on volume declines, have been what were once the largest brands; Budweiser, Miller Lite and Miller High Life. These have lost more than a quarter of their volume, losing a whopping 13million barrels/year of demand. These 3 brand declines account for 6% reduction in the entire beer market.

The popular myth is that this has been due to the rise of craft beers. And there is no doubt, craft beer sales have done well. Sales are up 80%. Many articles (including the WSJ)tout the growth of craft beers, which are ostensibly more tasty and appealing, as being the reason old-line brands have declined. It is an easy explanation to accept, and has largely gone unchallenged. Even the brewer of Budweiser, Annheuser-Busch InBev, has reacted to this argument by taking the incredible action of dropping clydesdale horses from their ads after 81 years – in an effort to woo craft beer drinkers, which are thought to be younger and less sentimental about large horses.

This all makes sense. Too bad it’s the wrong conclusion – and the wrong actions being taken.

Realize that craft beer sales are up from a small base, and today ALL craft beer sales still account for only 7.6% of the market. In fact, ALL craft beers combined sell only the same volume as the now smaller Budweiser. The problem with Budweiser sales – and sales of other big name brand beers – is a change in demographics.

Drinkers of Budweiser and Lite are simply older. These brands rose to tremendous dominance in the 1970s. Many of those who loved this brand are simply older – or dead. Where a hard working fellow in his 30s or 40s might enjoy a six pack after work, today that Boomer (if still alive) is somewhere between late 50s and 70s. Now, a single beer, or maybe two, will suffice thank you very much. And, equally challenging for sales, today’s Boomer is more often drinking a hard liquor cocktail, and a glass of wine with dinner. Beer drinking has its place, but less often and in lower quantities.

Meanwhile, Hispanics are a growing demographic. Hispanics are the largest non-white population in America, at 54million, and represent over 17% of all Americans. With a growth rate of 2.1%, Hispanics are also one of the fastest growing demographic segments – and increasingly important given their already large size. Hispanics are truly becoming a powerful buying group in American economics.

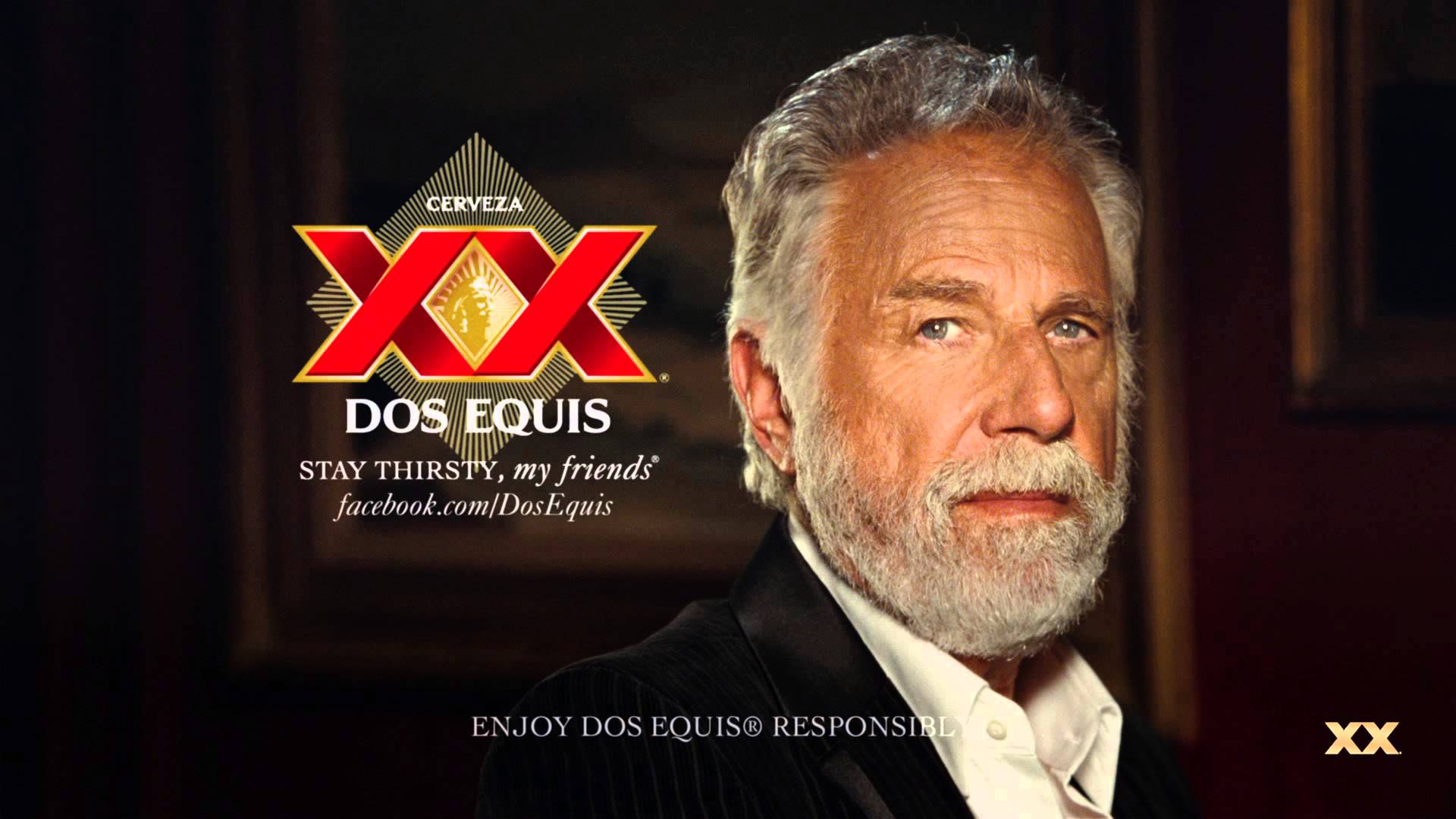

So, just as decline in Boomer population and consumption has hurt the once great beer brands, we can look at the growth in Hispanic demographics and see a link to sales of growing brands. Two significant (non-craft volume) beer brands that more than doubled sales since 2008 are Modelo Especial and Dos Equis. In fact, these were the 2 fastest growing brands in America, even though the first does no English language advertising at all, and the latter only lightly funds advertising with an iconic multi-year campaign. Together their sales total almost 5.4M barrels – which makes these 2 brands equal to 1/3 the ENTIRE craft beer marketplace. And growing 33% faster!

Chasing the myth of craft sales is doing nothing for InBev and MillerCoors as they try to defend and extend outdated brands. On the other hand, Heineken controls Dos Equis, and Constellation Brands controls Modello Especial. These two companies are squarely aligned with demographic trends, and well positioned for growth.

So, be careful the next time you hear some simple explanation for why a product or service is declining. The answer might sound appealing, but have little economic basis. Instead, it is much smarter to look at big trends and you’ll likely see why in the same market one product is growing, while another is declining. Trends – such as demographics – often explain a lot about what is happening, and lead you to invest much smarter.

by Adam Hartung | Dec 11, 2014 | Current Affairs, Defend & Extend, In the Whirlpool, Leadership, Lifecycle, Television, Web/Tech

The trend toward the death of broadcast TV as we’ve known it keeps moving forward. This trend may not happen as fast as the death of desktop computers, but it is a lot faster than glacier melting.

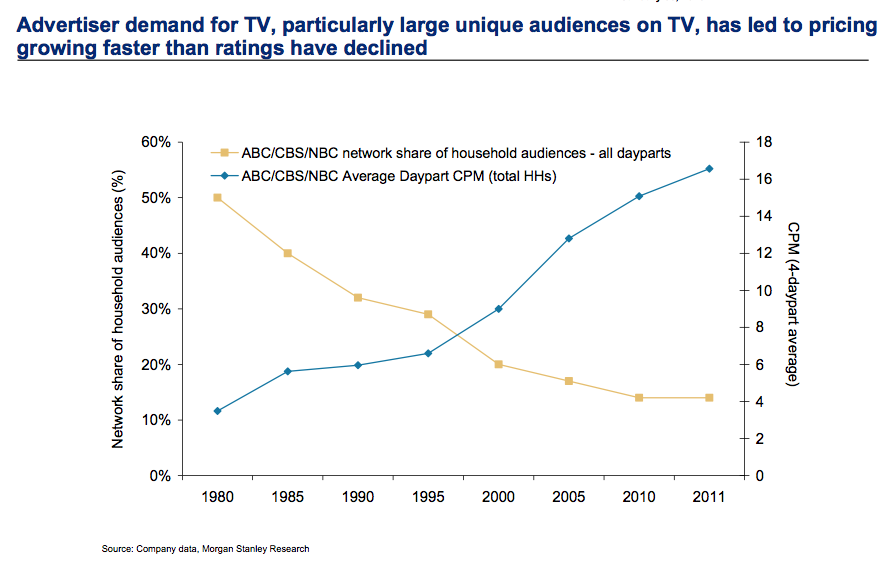

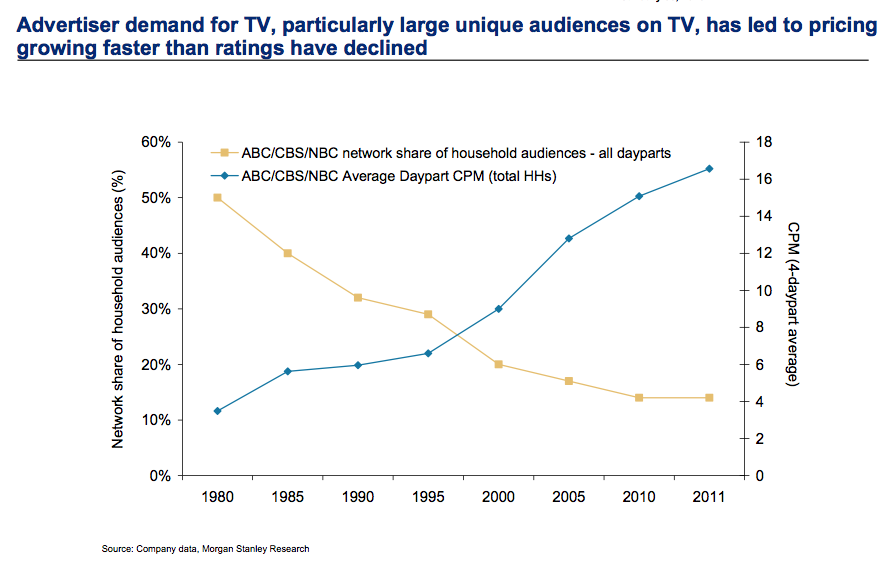

This television season (through October) Magna Global has reported that even the oldest viewers (the TV Generation 55-64) watched 3% less TV. Those 35-54 watched 5% less. Gen Xers (25-34) watched 8% less, and Millenials (18-24) watched a whopping 14% less TV. Live sports viewing is not even able to maintain its TV audience, with NFL viewership across all networks down 10-19%.

Everyone knows what is happening. People are turning to downloaded entertainment, mostly on their mobile devices. With a trend this obvious, you’d think everyone in the media/TV and consumer goods industries would be rethinking strategy and retooling for a new future.

But, you would be wrong. Because despite the obviousness of the trend, emotional ties to hoping the old business sticks around are stronger than logic when it comes to forecasting.

CBS predicted at the beginning of 2014 TV ad revenue would grow 4%. Oops. Now CBS’s lead forecaster is admitting he was way off, and adjusted revenues were down 1% for the year. But, despite the trend in viewer behavior and ad expenditures in 2014, he now predicts a growth of 2% for 2015.

That, my young friends, is how “hockey stick” forecasts are created. A lot of old assumptions, combined with a willingness to hope trends will be delayed, and you can ignore real data while promising people that the future will indeed look like the past – even when it defies common sense.

To compensate for fewer ads the networks have raised prices on all ads. But how long can that continue? This requires a really committed buyer (read more about CMO weaknesses below) who simply refuses to acknowledge the market has shifted and the dollars need to shift with it. That cannot last forever.

Meanwhile, us old folks can remember the days when Nielsen ratings determined what was programmed on TV, as well as what advertisers paid. Nielsen had a lock on measuring TV audience viewing, and wielded tremendous power in the media and CPG world.

But now AC Nielsen is struggling to remain relevant. With TV viewership down, time shifting of shows common and streaming growing like the proverbial weed Nielsen has no idea what entertainment the public watches. They don’t know what, nor when, nor where. Unwilling to move quickly to develop tools for catching all the second screen viewing, Nielsen has no plan for telling advertisers what the market really looks like – and the company looks to become a victim of changing markets.

Which then takes us to looking at those folks who actually buy ads that drive media companies. The Chief Marketing Officers (CMOs) of CPG companies. Surely these titans of industry are on top of these trends, and rapidly shifting their spending to catch the viewers with the most ads placed for the lowest cost.

You would wish.

Unfortunately, because these senior executives are in the oldest age groups, they are a victim of their own behavior. They still watch TV, so assume others must as well. If there is cyber-data saying they are wrong, well they simply discount that data. The Nielsen’s aren’t accurate, but these execs still watch the ratings “because it’s the best info we have” – a blatant untruth by the way. But Nielsen does conveniently reinforce their built in assumptions, and their hope that they won’t have to change their media spend plans any time soon.

Further, very few of these CMOs actually use social media. The vast majority watch their children, grandchildren and young employees use mobile devices constantly – and they bemoan all the activity on YouTube, Facebook, Instagram and Twitter – or for the most part even Linked-in. But they don’t actually USE these products. They don’t post information. They don’t set up and follow channels. They don’t connect with people, share information, exchange photos or tell stories on social media. Truthfully, they ignore these trends in their own lives. Which leaves them woefully inept at figuring out how to change their company marketing so it can be more relevant.

The trend is obvious. The answer, equally so. Any modern marketer should be an avid user of social media. Most network heads and media leaders are farther removed from social media than the Pope! They don’t constantly download entertainment, and exchanging with others on all the platforms. They can’t manage the use of these channels when they don’t have a clue how they work, or how other people use them, or understand why they are actually really valuable tools.

Are you using these modern tools? Are you actually living, breathing, participating in the trends? Or are you, like these outdated execs, biding your time wasting money on old programs while you look forward to retirement? And likely killing your company.

When trends emerge it is imperative we become part of that trend. You can’t simply observe it, because your biases will lead you to hope the trend reverts as you continue doing more of the same. A leader has to adopt the trend as a leader, be a practicing participant, and learn how that trend will make a substantial difference in the business. And then apply some vision to remain relevant and successful.

by Adam Hartung | Nov 12, 2014 | Current Affairs, Defend & Extend, In the Swamp, In the Whirlpool, Leadership

We see it all too often. A successful business seems to lose its way. Somehow, after decades of success, its results soften, then tumble and the company becomes a victim of its competition. We scratch our heads and wonder, “why did that happen?”

Pizza Hut is well on its way to disappearing. Kind of like Pizza Inn, A&W and Howard Johnson’s. And that seems kind of remarkable considering the company at one time defined pizza for most Americans. From a fast growing franchise in the 1960s to a high profile acquisition by PepsiCo in the 1970s, to anchoring the Yum Brands spin out from PepsiCo in 1997, Pizza Hut just finished 8 straight quarters of declining same store sales. Pizza Hut was once a concept as hot as Apple Stores, but now it looks more like Sears. How could this happen?

When Pizza Hut was growing it locked in on its success formula. And one of the biggest Lock-ins was its name. Pizza Hut was a place where you ate pizza, and the buildings all looked the same with that hut-like red roof. At a time when few Americans outside the northeast ate pizza, this Wichita, Kansas founded (and headquartered until the 1990s) company told people what a pizzeria should look like, and what you should eat.

The company was ardent about controlling what franchisees served. No nachos, or other trendy foods, because they didn’t fit the pizza theme. No delivery, because good pizza required you eat it immediately from the oven. Pizza should be thick and hearty, even served in a deep dish so you have plenty of bread and feel really full. Whether anyone in Italy ever a pizza anything like this really did not matter.

And Pizza Hut would help guide customers as to what toppings they wanted — and usually there should be at least 3 – by offering pre-designed pizzas with names like “meat lovers,” “supreme,” “super supreme” or “veggie lover’s” so an uninformed clientele (originally prairie state, then midwestern, then expanding into the southwest and the south) could buy the product without a lot of fuss.

This success formula may sound cliche today, but it worked. And it worked really well for 30 years, then pretty well for another 10-15. But, eventually, doing the same thing over, and over, and over, and over had less appeal. Almost everyone in the country knew what a Pizza Hut was, what the stores looked like and what the product was like. Competitors came along by the dozens with all kinds of variations, and different kinds of service – like being in a mall, or delivering the product. Inevitably this competition led to price wars. To keep customers Pizza Hut had to lower its prices, even offering 2 pizzas for the price of one. Pizza Hut never lost track of its success formula, and never stopped doing what once made it great. But margins eroded, and then sales started declining.

Lots of people don’t care about Pizza Hut any more. They want an alternative. An alternative product, like California Pizza Kitchen or Wolfgang Pucks. Or an alternative to pizza altogether like the new “fast casual” chains such as Chipotle’s, Baja Fresh or Panera. For a whole raft of reasons, people decided that although they once ate Pizza Hut (even ate a LOT of it) they were going to eat something else.

But Pizza Hut was locked in. First, its name. Pizza. Hut. To fulfill the “brand promise” of that name everything about that store is pre-designed. From the outside to the inside tables to the equipment in the kitchen. 6,300 stores that are almost identical. Any change and you have to make 6,300 changes. Adding new product categories means reprinting 126,000 menus, changing 6,300 kitchen layouts, buying 6,300 new ovens, figuring out the service utensils for 6,300 wait staff. That’s lock-in. Making any change is so hard that the incentive is entirely toward improve what you’ve always done rather than doing something new.

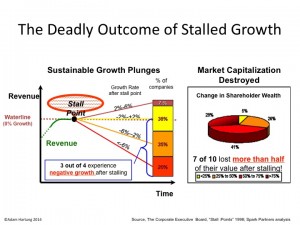

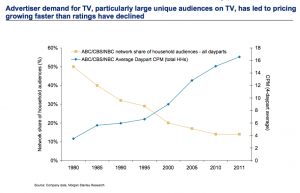

Growth Stalls are Deadly

Eventually, like Pizza Hut, growth stalls. It only takes 2 quarters of declining sales to hit a growth stall, and when that happens less than 7% of businesses will ever again consistently grow at a meager 2%. Growth stalls tell us “hey, the market shifted. What you’re doing isn’t selling any more.”

But most management teams don’t think about a market shift, and instead react by trying to do more of the same. They treat this like its an operational problem. More quality campaigns, more money spent on advertising, more promotions, asking employees to work a little harder, more product for the same (or lower) price – more, better, faster, cheaper. But this doesn’t work, because the problem lies in a market shift away from your “core” that requires an entirely different strategy.

Because management is incented to ignore this shift as long as possible, the company soon becomes irrelevant. Customers know they’ve been going to competitors, and they start to realize it’s been a long time since they bought from that old supplier. They realize their interest in that old company and its products has simply gone away. They don’t pay attention to the ads. And they don’t have any interest in new product announcements. Actually, they find the company irrelevant. Even when the discounts are big, they don’t buy. They do business where they identify with the company and its products, even when those products cost more.

And thus the results start to tumble horribly. Only by now management is so far removed from market trends that it has no idea how to regain relevancy. In Pizza Hut’s case, leadership is undertaking what they’d like to think is a brand overhaul that will change its position in customers’ minds. But, unfortunately, they are doing the ultimate in defend & extend management to try and save the old success formula.

Pizza Hut is introducing a maze of new ways to have its old product, in its old stores. 10 crust choices, 6 sauce choices, 22 of those pre-designed pizza offerings, 5 different liquids you can have dribbled over the pizza, and a rash of exotic new toppings – like banana. So now you can order your pizza 1,000 different ways (actually, more like 10,000.) Oh, and this is being launched with a big increase in traditional advertising. In other words, an insane implementation of what the company has always done; giving customers an American style pizza, in a hut, promoted on TV – even most likely buying what is now considered iconic – a Super Bowl ad.

Yum Brands investors have reasons to be concerned. Pizza Hut is really important to sales and earnings. But its leaders are intent on doing more of the same, even though the market has already shifted. The prognosis does not look good.

by Adam Hartung | Oct 28, 2014 | Current Affairs, Defend & Extend, Food and Drink, In the Swamp, Leadership, Lock-in, Television

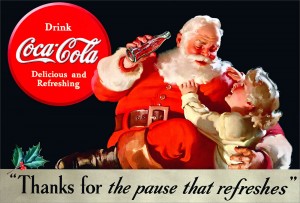

I’m a “Boomer,” and my generation could have been called the Coke generation. Our parents started every day with a cup of coffee, and they drank either coffee or water during the day. Most meals were accompanied by either water, or iced tea.

But our generation loved Coca-Cola. Most of our parents limited our consumption, much to our frustration. Some parents practically refused to let the stuff in the house. In progressive homes as children we were usually only allowed one, or at most two, bottles per day. We chafed at the controls, and when we left home we started drinking the sweet cola as often as we could.

It didn’t take long before we supplanted our parent’s morning coffee with a bottle of Coke (or Diet Coke in more modern times.) We seemingly could not get enough of the product, as bottle size soared from 8 ounces to 12 to 16 and then quarts and eventually 2 liters! Portion control was out the window as we created demand that seemed limitless.

Meanwhile, Americans exported our #1 drink around the world. From 1970 onward Coke was THE iconic American brand. We saw ads of people drinking Coke in every imaginable country. International growth seemed boundless as people from China to India started consuming the irresistible brown beverage.

My how things change. Last week Coke announced third quarter earnings, and they were down 14%. The CEO admitted he was struggling to find growth for the company as soda sales were flat. U.S. sales of carbonated beverages have been declining for a decade, and Coke has not developed a successful new product line – or market – to replace those declines.

Coke is a victim of changing customer preferences. Once a company that helped define those preferences, and built the #1 brand globally, Coke’s leadership shifted from understanding customers and trends in order to build on those trends towards defending & extending sales of its historical product. Instead of innovating, leadership relied on promotion and tactics which had helped the brand grow 30 years ago. They kept to their old success formula as trends shifted the market into new directions.

Coke began losing its relevancy. Trends moved in a new direction. Healthfulness led customers to decide they wanted a less calorie rich, nutritionally starved drink. And concerns grew over “artificial” products, such as sweeteners, leading customers away from even low calorie “diet” colas.

Meanwhile, younger generations started turning to their own new brands. And not just drinks. Instead of holding a Coke, increasingly they hold an iPhone. Where once it was hip to hang out at the Coke machine, or the fountain stand, now people would rather hang out at a Starbucks or Peet’s Coffee. Where once Coke was identified and matched the aspirations of the fast growing Boomer class, now it is replaced with a Prada handbag or other accessory from an LVMH branded luxury product.

Where once holding a Coke was a sign of being part of all that was good, now the product is largely passe. Trends have moved, and Coke didn’t. Coke leadership relied too much on its past, and failed to recognize that market shifts could affect even the #1 global brand. Coke leaders thought they would be forever relevant, just do more of what worked before. But they were wrong.

Unfortunately, CEO Muhtar Kent announced a series of changes that will most likely further hurt the Coca-Cola company rather than help it.

First, and foremost, like almost all CEOs facing an earnings problem the company will cut $3B in costs. The most short-term of short-term actions, which will do nothing to help the company find its way back toward being a prominent brand-leading icon. Cost cuts only further create a “hunker-down” mindset which causes managers to reduce risk, rather than look for breakthrough products and markets which could help the company regain lost ground. Cost cutting will only further cause remaining management to focus on defending the past business rather than finding a new future.

Second, Coca-Cola will sell off its bottlers. Interestingly, in the 1980s CEO Roberto Goizueta famously bought up the distributorships, and made a fortune for the company doing so. By the year 2000 he was honored, along with Jack Welch of GE, as being one of the top 2 CEOs of the century for his ability to create shareholder value. But now the current CEO is selling the bottling operations – in order to raise cash. Once again, when leadership can’t run a business that makes money they often sell off assets to generate cash and make the company smaller – none of which benefits shareholders.

Third, fire the Chief Marketing Officer. Of course, somebody has to be blamed! The guy who has done the most to bring Coca-Cola’s brand out of traditional advertising and promote it in an integrated manner across all media, including managing successful programs for the Olympics and World Cup, has to be held accountable. What’s missing in this action is that the big problem is leadership’s fixation with defending its Coke brand, rather than finding new growth businesses as the market moves away from carbonated soft drinks. And that is a problem that requires the CEO and his entire management team to step up their strategy efforts, not just fire the leader who has been updating the branding mechanisms.

Coca-Cola needs a significant strategy shift. Leadership focused too long on its aging brands, without putting enough energy into identifying trends and figuring out how to remain relevant. Now, people care a lot less about Coke than they did. They care more about other brands, like Apple. Globally. Unless there is a major shift in Coke’s strategy the company will continue to weaken along with its primary brand. That market shift has already happened, and it won’t stop.

For Coke to regain growth it needs a far different future which aligns with trends that now matter more to consumers. The company must bring forward products which excite people ,and with which they identify. And Coke’s leaders must move much harder into understanding shifts in media consumption so they can make their new brands as visible to newer generations as TV made Coke visible to Boomers.

Coke is far from a failed company, but after a decade of sales declines in its “core” business it is time leadership realizes takes this earnings announcement as a key indicator of the need to change. And not just simple things like costs. It must fundamentally change its strategy and markets or in another decade things will look far worse than today.

by Adam Hartung | Oct 15, 2014 | Current Affairs, Defend & Extend, Innovation, Leadership

The Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA) is down 400 points today. Down 8% since its high 3 weeks ago, and now showing no gains for the entire year.

Oh my!

There seems little immediate explanation for the fast drop. When major financial news outlets say it is caused by Ebola fears you can be assured those being asked “why” are clutching at straws. They have no clear explanation. This could be nothing more than a 10% correction, a short-term break in the long-term bull which has gone on for a remarkable 3 years.

But, investors are not out of the woods. Will the market continue to even greater highs? Will this Bull market continue for many more months?

There is at least one good reason investors should be concerned.

For the last decade, corporations have been about the biggest buyers of equities. Since 1998 85% of all corporate earnings have gone into share buyback programs. Buybacks do not add value to a company, they merely reduce the number of shares. By reducing the number of outstanding shares, earnings per share (EPS) can go up, even if earnings do not go up. But reducing the denominator the answer increases, even if the numerator does not change – or goes up only slightly. Thus per share earnings have increased, on average, 6.2% quarterly – more than double the revenue increase of only 2.6%. All artificial growth – not a true increase in corporate performance.

In 2014 95% of S&P 500 corporate earnings will go toward buybacks and dividends – in effect increasing investor returns while doing nothing to make the companies better. In the 1st quarter money paid to investors exceeded S&P 500 profits, and likely will do so again in the 3rd quarter. All of which props up stocks in the short-term, but removes cash from the companies. Cash which could be used to invest in growing revenues long-term.

This is not new. In the last decade, cash for buybacks has doubled. Today, 30% of free cash flow goes into stock repurchases, a rate double that of 2002.

Meanwhile investment in plant and equipment has declined from over 50% of cash flow to under 40%. Today the average age of plant and equipment in the USA is 22 years – the oldest it has been since 1956! In an era of almost free money – with interest rates in low single digits and often less than inflation – corporations are taking on debt NOT to invest in growth, but rather to simply pay out more to shareholders in efforts to prop up stock prices. And they’ve done it now for so long – over a decade – that the short-term has become the long-term, and there is precious little invested base from which future revenues and profits can grow.

Leaders for the past several years have failed their investors by not investing cash flow in innovation for long-term growth. Instead of new products creating new markets, the only innovations being funded have been focused solely on defending and extending past product sales. With an inordinate fear of risk, and a complete lack of future vision, what passes for innovation are attempts to sustain the old stuff rather than create something new.

For example, P&G’s leaders gave investors the “Basic” line of products. These were literally less good products, a throwback to earlier quality levels, repackaged and sold at a lower price. The last really “new” product from P&G was the Swiffer mop – and that was back in 1999. Since then we’ve had what seems to be infinite variations of that product, all intended to extend its life. Where’s the new “great thing” that will jump revenues and sustain profits for years into the future?

There are exceptions to this generalization. Of course Facebook is changing media and advertising, while Netflix is redeveloping how we enjoy entertainment. Amazon has us buying on-line instead of in retail stores, and wondering if we’ll someday receive same-day shipping via drones. And Apple has moved us into the world of apps encouraging us to buy smartphones and tablets while dumping land-lines, cell phones and PCs. So there are some serious innovators out there.

But, for long-term investors overall, there is a big reason to worry. This DJIA drop may be merely a “normal 10% correction.” But, equities cannot go up forever on declining cash flow from ancient investments of previous leaders and interest-free debt accumulation. For equities to continue their upward trajectory at some time companies have to launch new products, create new markets and generate sustainable long-term profits. In other than a handful of noteworthy companies, there isn’t much of this kind of investment happening today – or over the last 10-15 years.

Eventually, costs of capital will go up. And cash flow from old investments will go down. If there aren’t real sales growth opportunities there could be declining real profits. Without buybacks to feed the bull, a raging bear could overtake the scene.

Oh my.

by Adam Hartung | Sep 30, 2014 | Current Affairs, Disruptions, In the Rapids, Innovation, Leadership, Web/Tech

Will the new Apple Pay product, revealed on iPhone 6 devices, succeed? There have been many entries into the digital mobile payments business, such as Google Wallet, Softcard (which had the unfortunate initial name of ISIS,) Square and Paypal. But so far, nobody has really cracked the market as Americans keep using credit cards, cash and checks.

But that looks like it might change, and Apple has a pretty good chance of making Apple Pay a success.

First, a look at some critical market changes. For decades we all thought credit card purchases were secure. But that changed in 2013, and picked up steam in 2014. With regularity we’ve heard about customer credit card data breaches at various retailers and restaurants. Smaller retailers like Shaw’s, Star Markets and Jewel caused some mild concern. But when top tier retailers like Target and Home Depot revealed security problems, across millions of accounts, people really started to notice. For the first time, some people are thinking an alternative might be a good idea, and they are considering a change.

In other words, there is now an underserved market. For a long time people were very happy using credit cards. But now, they aren’t as happy. There are people, still a minority, who are actively looking for an alternative to cash and credit cards. And those people now have a need that is not fully met. That means the market receptivity for a mobile payment product has changed.

Second let’s look at how Paypal became such a huge success fulfilling an underserved market. When people first began on-line buying transactions were almost wholly credit cards. But some customers lacked the ability to use credit cards. These folks had an underserved need, because they wanted to buy on-line but had no payment method (mailing checks or cash was risky, and COD shipments were costly and not often supported by on-line vendors.) Paypal jumped into that underserved market.

Quickly Paypal tied itself to on-line vendors, asking them to support their product. They went less to people who were underserved, and mostly to the infrastructure which needed to support the product. By encouraging the on-line retailers they could expand sales with Paypal adoption, Paypal gathered more and more sites. The 2002 acquisition by eBay was a boon, as it truly legitimized Paypal in minds of consumers and smaller on-line retailers.

After filling the underserved market, Paypal expanded as a real competitor for credit cards by adding people who simply preferred another option. Today Paypal accounts for $1 of every $6 spent on-line, a dramatic statistic. There are 153million Paypal digital wallets, and Paypal processes $203B of payments annually. Paypal supports 26 currencies, is in 203 markets, has 15,000 financial institution partners – all creating growth last year of 19%. A truly outstanding success story.

Back to traditional retail. As mentioned earlier, there is an underserved market for people who don’t want to use cash, checks or credit cards. They seek a solution. But just as Paypal had to obtain the on-line retailer backing to acquire the end-use customer, mobile payment company success relies on getting retailers to say they take that company’s digital mobile payment product.

Here is where Apple has created an advantage. Few end-use customers are terribly aware of retail beacons, the technology which has small (sometimes very small) devices placed in a store, fast food outlet, stadium or other environment which sends out signals to talk to smartphones which are in nearby proximity. These beacons are an “inside retail” product that most consumer don’t care about, just like they don’t really care about the shelving systems or price tag holders in the store.

Launched with iOS 7, Apple’s iBeacon has become the leader in this “recognize and push” technology. Since Apple installed Beacons in its own stores in December, 2013 tens of thousands of iBeacons have been installed in retailers and other venues. Macy’s alone installed 4,000 in 2014. Increasingly, iBeacons are being used by retailers in conjunction with consumer goods manufacturers to identify who is shopping, what they are buying, and assist them with product information, coupons and other purchase incentives.

Thus, over the last year Apple has successfully been courting the retailers, who are the infrastructure for mobile payments. Now, as the underserved payment issue comes to market it is natural for retailers to turn to the company with which they’ve been working on their “infrastructure” products.

Apple has an additional great benefit because it has by far the largest installed base of smartphones, and its products are very consistent. Even though Android is a huge market, and outsells iOS, the platform is not consistent because Android on Samsung is not like Android on Amazon’s Fire, for example. So when a retailer reaches out for the alternative to credit cards, Apple can deliver the largest number of users. Couple that with the internal iBeacon relationship, and Apple is really well positioned to be the first company major retailers and restaurants turn to for a solution – as we’ve already seen with Apple Pay’s acceptance by Macy’s, Bloomingdales, Duane Reed, McDonald’s Staples, Walgreen’s, Whole Foods and others.

This does not guarantee Apple Pay will be the success of Paypal. The market is fledgling. Whether the need is strong or depth of being underserved is marked is unknown. How consumers will respond to credit card use and mobile payments long-term is impossible to gauge. How competitors will react is wildly unpredictable.

But, Apple is very well positioned to win with Apple Pay. It is being introduced at a good time when people are feeling their needs are underserved. The infrastructure is primed to support the product, and there is a large installed base of users who like Apple’s mobile products. The pieces are in place for Apple to disrupt how we pay for things, and possibly create another very, very large market. And Apple’s leadership has a history of successfully managing disruptive product launches, as we’ve seen in music (iPod,) mobile phones (iPhone) and personal technology tools (iPad.)