by Adam Hartung | Aug 10, 2017 | Entrepreneurship, Leadership, Web/Tech

Recently, I wrote a column about 10 young entrepreneurs. Originally I titled it “10 under 20” but the Forbes editors thought that was too close to their “30 under 30” column so they changed it to “10 Great Lessons From Millennial Entrepreneurs.” I didn’t like that title, because it implied these were “great” entrepreneurs, and I really didn’t think they were all that great. Now that some time has gone by, I really regret having written the column.

I’ve written this column at Forbes for almost 7 years. So I am pitched for unsolicited columns every day by PR firms. On average, about 10 pitches every day. But nothing compared with the onslaught of emails I received after the millenial column. Firm after firm, and even individuals, contacted me by email, on Facebook, Linked-in, and Twitter to tell me about some incredible young person who just absolutely needed to be written about. You would think that every high school, and small university, in America had at least one, if not multiple, young prodigies all of which were destined to change the world. It was an avalanche of pitches, from which I could not even begin to fully read, much less respond.

But, almost universally these businesses were not that fantastic. Most were the modern day equivalent of someone opening a lawn service in 1960. Simple businesses that had little to distinguish them. Many had no revenues, and many were little more than somebody’s idea of a business they would like to build. Those that had revenues were so small as to be meaningless, and almost none made any impact on their industry or competition.

The pitches were, without a doubt, the most hyped pitches I have ever received. Over and over I kept asking “why would anyone think this is in the slightest interesting?

The only reason this is being pitched is because it involves someone under the age of 25. And usually that someone lacks any credentials and offers no new insight to the industry or product.”

2 -Not a sustainable business

Writing an app is not a business. Even if it sold a few thousand copies. Nor is trading baseball cards, or selling someone else’s stuff on eBay. Nor is buying bitcoins. By and large, 99% of the pitches were for one-product opportunities that clearly lacked any sense of being a sustainable business which could produce recurring revenue over multiple years. Almost none had any employees, and those that did had a mere handful with no plans to scale any larger.

At best most were simply a single shot situation which generated some revenue for the millennial founder. And most could only pay the founder because the business had no overhead and a highly subsidized cost structure due to support from parents. Many had no, or little, profits and there was nowhere near enough cash to repay traditional investors. Because there was no cost for financing, overhead or even variable activities like payroll, these businesses could not be considered a success in any traditional sense.

3 – These were not really entrepreneurs

French economist Jean-Baptiste Say coined the term entrepreneur. He used it to describe people who seek out inefficient uses of resources and capital then redeployed them into more productive, higher-profit uses. None of the pitched businesses actually redeployed any resources. And none really developed a new industry that created greater productivity. These were just ideas that manifested into a product that fit an immediate need. Most used an existing infrastructure, such as an app store, to do one thing – like sell an app. Maybe someday they’ll write another – but there was no indication any research was happening, customer analysis or market testing to create a long-term business.

Additionally, for entrepreneurs there is some element of risk-taking. For taking risk, by investing in something where others won’t invest, there is the opportunity for outsized returns. But these folks didn’t take any risk at all. It wasn’t their money they invested, but rather their family’s. Most either lived at home, or lived in housing paid for by family (such as a college dorm room.) Most had nothing invested in their “business” other than personal time, and if this failed there was almost nothing lost. And most had minimal gains relative to the size of the risk they undertook with other people’s resources.

And they all lacked any sense of a business plan. Now I’m all for innovation and trying new things, but business success requires the ability to generate ongoing revenue for a prolonged period that covers all costs and creates returns for investors. These folks simply promoted ideas with no description of how this was to be a long-term profitable venture that succeeded for customers, suppliers and financial backers. I found that I would not have been an investor in hardly any of these “businesses” and surely would not recommend readers to back them.

4 – These folks were big self-promoters, not business promoters

Almost to a pitch every story was about some individual – not a business success. I was told over and over and over about how some 17, 18, 19 or 20 year old was absolutely a genius; a modern miracle of incredible business insight. Yet, there was little to back-up these claims. In the end, these were just young folks who had some sense of ambition and fortitude that were doing a few experiments and had (in some instances, not all) sold a few things. But their stories really weren’t that interesting.

One young fellow washed vehicles. He got a contract to wash trucks. And he had expanded his truck washing capability to multiple trucking companies. OK, ambitious and hard working. But nothing fantastic. No technology breakthrough. Just a basic service that he sold cheaply enough to win some contracts. But, he was unwilling to discuss his margins, how much he paid himself or others and how he financed the company or paid a return to his backers. Yet, he was certain that he could franchise his truck washing business and soon enough he would be the next Ray Kroc. He, and his PR person (and it was unclear who paid her) failed to realize that his story might be interesting in 20 years after he proved he could build the next McDonald’s making himself, his investors and his franchisees rich.

Add onto this the fact that almost all of these people had nothing good to say about anyone older. For some reason I was informed over and again that nobody over 40 could really understand how brilliant this person is, and how guaranteed was future success. These people universally had no value for advice from people older than them,  no value for those with experience (all experience was seen as irrelevant to their brilliant insight,) and no value for education. There was no reason to study business practices, or even business history, much less anything like engineering, because they simply had taught themselves all they needed to know – and if they needed to know anything else they would teach that to themselves as well.

no value for those with experience (all experience was seen as irrelevant to their brilliant insight,) and no value for education. There was no reason to study business practices, or even business history, much less anything like engineering, because they simply had taught themselves all they needed to know – and if they needed to know anything else they would teach that to themselves as well.

I kept saying to myself “get over yourself kid. You are working hard, but so are a lot of other people. You really haven’t accomplished anything of merit yet. And there’s not really anything here that indicates you will achieve great things. You may win awards for just showing up at school, or at the soccer match, but in business you have a LOT more to prove than you can show up and possibly accomplish some of the basics. Once..”

5 – No sense of how to build something, or even engage in quid pro quo

Bill Gates built a company that produced software millions of people wanted. Steve Jobs built a company that made devices (computers initially) that millions wanted. Henry Ford made cheap cars that millions of people wanted. Mark Zuckerberg created an interaction engine that millions of people wanted (and advertisers would pay to reach.) These founders understood that building a successful business meant combining multiple resources into an organization that functions capably to build products and markets.

If you asked them “why should I write about you?” they would answer, “to tell folks about the improvement in their life from my company’s products.”

When I asked these millennial entrepreneurs why I should write about them, the answer was “because I’m young and great and going places.”

Worse, when I pointed out that in today’s world columnists rely on readers, and therefore columnists want to know the topic will generate reads, they were without even a good idea of how a column on them would generate reads. When I asked “will you promote this through a large social media conduit to drive readers to the column?” they responded with “but isn’t that what Forbes does, bring in readers? I think you should write about me so Forbes readers can become enlightened. Why should I be asked to promote your column, isn’t that what you and Forbes do?”

It was completely unclear to me who was paying for these PR firms. But to them, and to the hundreds of millennials who sent me Facebook, Linked-in and Twitter messages:

- Quit focusing on yourself and actually accomplish something. Don’t be proud you’re a drop-out, go finish school.

- Listen more and talk less. You really don’t have much that’s interesting to say. Pay attention to those who are older, wiser and could help you reach your goals. You need them, and most of them don’t need you. You’re really not as interesting as you think you are.

- Get some education. Bill Gates and Steve Jobs are my age – not yours. Every generation needs more skills than the one before it. Mark Zuckerberg is THE exception, not the rule. Dropping out of Harvard did not make him great. Before you decide you have all the answers, go learn what the questions are. Learn how to think, how to reason, before you decide you know all that’s needed to take action.

- Quit living on subsidies. If your parents or grandparents or aunts and uncles are paying for your rent, or car, or supplies then you still don’t understand basic economics. Become self-sufficient. Make enough money to buy your own new car, buy your own house, and pay 100% of your bills – and even enough that you could afford to raise children. Until you are self-reliant it is very hard to take you seriously as a business leader.

- Life is NOT a one-round event. You are very likely to live 100 years. Do you have the skills to maintain your lifestyle for that full 100 years? Quit crowing about the 1 success (by your definition) you’ve had so far and instead figure out how you’ll lead a productive 100 year existence. You’re only 20% of the way there.

I hear folks say we need to advance millennials onto boards of directors for public companies. Or fund their new ventures without business plans or traditional benchmarks. Or put them into highly placed positions of major corporations. I can’t agree with that. From what I observed, millennials are similar to all other young people. They don’t know what they don’t know. And only time, failures, successes, education (formal and informal) and hard work will prepare them to be tomorrow’s leaders.

I started my entrepreneurial life while a college junior. I was lucky enough to hook up with several people at least a decade older, and they found investors that were a generation older. The company made computer hardware, and largely due to good luck as well as hard work the company was successfull, and was sold for a great return to the investors and some money for the founders. Simultaneously I completed my undergraduate degree in 4 years, summa cum laude. What made me most excited about that experience was not trying to be featured in any journal, but rather that the folks at the Harvard Business School felt this experience was good enough to admit me to their institution to complete an MBA. And there is no doubt in my mind that what I learned in college, and grad school, was incredibly important to generating a lifetime of ongoing business accomplishments – long after that first company disappeared into the dustbin of obsolete technology.

by Adam Hartung | Jul 31, 2017 | In the Flats, Innovation, Investing, Leadership, Marketing

Amid all the political news last week it was easy to miss announcements in the business world. Especially one that was relatively small, like Starbucks announcement on Thursday July 27, 2017 that it was closing all 379 of its Teavana stores. While these will be missed by some product fanatics, the decision is almost immaterial given that these units represent only about 3% of Starbucks US stores, and about 1.5% of the 25,000 Starbucks globally.

Yet, closing Teavana is a telltale sign of concern for Starbucks investors.

Starbucks founding CEO Howard Schultz returned to the top job in January, 2008, promising to get out of distractions such as music production, movie production, internet sales, grocery products, liquor products and even in-store food sales in order to return the company to its “core” coffee business. Since then Starbucks valuation has risen some 5.5-6 fold, from $9.45/share to the recent range of $54 to $60 per share. A much better return than the roughly doubling of the Dow Jones Industrial Average over the same timeframe.

Yet, one should take time to evaluate what this closing means for the long-term future of Starbucks. This is the second time Starbucks made an acquisition only to shut it down. In 2015 Starbucks closed all 23 La Boulange bakery cafes, with little fanfare. Now, after paying $620M to buy Teavana in 2012, they are closing all those stores. While leadership blamed its decision on declining mall visits (undoubtedly a fact) for the closures, Teavana is not missing goals due to the Amazon Effect. There are multiple options for how to market Teavana’s fresh and packaged products far beyond mall store locations. Choosing to close all stores indicates leadership has minimal interest in the brand.

Starbucks’ focus leaves little opportunity for new growth

It increasingly appears that today’s Starbucks literally isn’t interested, or able, to do anything other than build, and operate, more Starbucks stores. And Starbucks is clearly doubling down on its plans to be Starbucks store-centric. The company opened 575 new units in the last year, and announced plans to open more stores creating 68,000 additional US jobs in the next 5 years. Further, Starbucks is paying $1.3B to buy the half of its China business previously owned by a partner. Clearly, leadership continues to tighten company focus on the “core” coffee store business for the future.

This sounds great short-term, given how well things have gone the last 8 years. But there are concerns. Sales are up 4% last quarter, but that is wholly based upon higher prices. Customer counts are flat, indicating that stores are not attracting new customers from competitors. Sales gains are due to average ticket prices increasing 5%, which is marginal and likely refers to higher priced products. Starbucks is now relying completely on new stores to create incremental growth, since bringing in new customers to existing stores is not happening.

Frequently this stagnant store sales metric indicates store saturation. A bad sign. Does the US, or international markets, really need more, new Starbucks stores? It was 2010 when comedian Lewis Black had a successful viral rant (PG version) claiming that when he observed a Starbucks across the street from another Starbucks he knew it was the end of civilization.

What happens when the market doesn’t need new Starbucks stores?

One does have to wonder when the maximum number of Starbucks will be reached. Especially given the ever growing number of competitors in all markets. Direct competitors such as Caribou Coffee, The Coffee Bean, Seattle’s Best, Gloria Jean’s, Costa, Lavazza, Tully’s, Peet’s and literally dozens of chain and independent coffee shops are competing for Starbucks’ customers. Simultaneously competition from low priced alternatives is emerging from brands like Dunkin Donuts and McDonald’s, now catering more to coffee lovers. And non-coffee fast casual shops are seeking to attract more people for congregating, such as Panera, Fuddruckers, Pei Wei, TGI Friday’s and others. All of these are competitors, either directly or indirectly, for the customer dollars sought by Starbucks. Are more Starbucks stores going to succeed?

As McDonald’s, Pizza Hut and other fast food chains learned the hard way, there comes a time when a brand has built all the market needs. Then leadership has to figure out how to do something else. McDonald’s invested heavily in Boston Market and Chipotle’s, but let those high growth operations go when it decided to refocus on its “core” hamburger business – leading to heavy valuation declines. Starbucks is closing Teavana, but should it? When will Starbucks saturate? And what will Starbucks do to grow when that happens?

Starbucks has had a great run. And that run appears not fully over. But long-term investors have reason to worry.

Is it smart to make such a huge bet on China?

Will store growth successfully continue, with all the stores that already exist?

Will direct and indirect competitors eat away at market share?

What will Starbucks do when it has reached it market maximum, and it doesn’t seem to have any emerging new store concepts to build upon?

by Adam Hartung | Jul 28, 2017 | Disruptions, Leadership

The news was filled this week with stories about President Trump’s “unorthodox” management style. From tweeting his thoughts on replacing Attorney General Jeff Sessions, to tweeting his multiple positions on healthcare law changes, to hiring a new communications director who lets loose with expletive-laden rants, people have been left questioning what sort of leadership style President Trump is trying to display.

Donald Trump promised to be a “disruptive leader”

Donald Trump ran for office as an outsider who pledged to disrupt Washington politics. This was a message well received by many people. They felt that “business as usual” in national politics was not serving them well, so they wanted change. To them a disruptor could find a way to steer national politics back onto a course that was more aligned with the conservative middle Americans. These voters felt that a businessman entrepreneur just might be the kind of leader who could disrupt the status quo in order to get something done for them.

Unfortunately, things have not worked out that way. And largely this can be traced to the leadership style of President Trump. Rather than a dedicated disruptor, ready to implement change, President Trump has proven to be a chaos generator that has stymied progress on pretty nearly all issues. Disruptions can lead to positive change. Chaos leads to stagnation and degradation as the system searches for homeostasis and a path forward.

From early age, we are taught not to be disruptive. Disrupting someone during school, religious ceremonies, entertainment events leads to distractions and an inability to remain focused on the goal. Thus, we are mostly taught to listen, learn and do what we’re told. However, we also recognize there is a time to be disruptive, because the act of intervening in the process at times can lead to far more positive outcomes than maintaining the course.

But it takes good judgement, and reasoned action, to be a positive disruptive influence. If you are in a crowded theater and you recognize a blaze it is time to disrupt the stage presentation. But you have a choice. If you jump up and yell “fire” you will create chaos. Everyone suddenly realizes a problem, but with no idea how to deal with it a thousand different solutions emerge simultaneously. Everyone starts looking out for their own interest, and they trample those around them in an effort to implement their own plans. Many people get hurt, and frequently the goal of saving everyone by disrupting the presentation is lost in carnage created by the bad disruption leading to chaos.

What is successful disruptive leadership?

So, if you sense a pending fire you are far smarter to develop a plan, such as activating the evacuation notices and opening the exits, prior to making an alert. And then, instead of yelling “fire” you say to folks “an issue has developed, please make your way down the evacuation routes to the open exits while we deal with the situation. Please remain calm so everyone can exit safely.” Your disruption can lead to successful outcome, rather than chaos.

I’ve spent over 20 years focusing on how disruptions can lead to positive change. And it is clear that with disruptive innovations, and disruptive business models, their success relies on leaders that understand how to implement disruptions effectively. Leadership matters.

Disruptive leaders think very hard about their desired outcomes, and they go to great lengths to describe what those future, better outcomes will look like. They then create a plan of action before they do anything. While the innovation might well be known, they are very, very careful to think through how that innovation will be adopted, then nurtured to gain acceptance and hopefully become mainstream. These leaders are very careful about their language choices, and where they communicate, in order to encourage people to accept their vision and join with their plan. They seek adoption rather than confrontation, and they discuss the desired outcomes rather than the disruption itself. They gain trust and build a consensus for change, and then they systematically roll out their plan, which they adjust as necessary to meet unexpected market conditions. They gradually move people along the implementation route by relentlessly focusing on the better outcome and reducing the fear inherent in accepting the disruption.

Five ways Donald Trump fails as a successful disruptive leader:

- The President has not portrayed a superior outcome which he can use to rally people to his viewpoint. Despite talking about “making America great again” there is no picture of what that looks like. What is this future “great” America he envisions and wants us to buy into? What are the poor outcomes of today that he will greatly improve, leading to vastly superior future outcomes? Without a clear description of the future, it is hard to gain supporters. For example, will changes in health care improve care? Lower the cost? What are the benefits, the better outcomes, of change? What is the benefit of replacing the sitting attorney general?

- The President has not laid out his plan for bringing people on board to his future. Look at the recent effort to implement new health care legislation. At times the President has said there is a need to repeal current legislation and replace it, but he has offered no description of what the replacement should look like. At other times he has said to repeal current legislation, but he has offered no insight into how that would lead to better outcomes than the current legislation provides. At yet other times he has said to do nothing, and he expressed his hope that current legislation would fail even though he admitted this would lead to an outcome far worse than the status quo. By not creating a plan, and bringing people on board to his plan, he has created chaos in the legislative process.

- President’s Trumps messages are built on negative language, not positive language about the future. His messages are long on how some person or current situation is weak, rather than explaining what a strong future would look like. He frequently attacks his predecessor, or his former electoral opponent, but does little to say what is good about his Presidency or recommendations or what he is specifically going to do that will create better outcomes. He frequently talks about firing people in his administration, but talks little about the specifics of what good work people in his administration are doing. These language choices are exclusive, not inclusive, and they create chaos among those who work in his administration, and members of Congress. Instead of understanding the President’s goals and objectives people are wondering “what will he say next?” And by appointing a communications director who uses outrageous, unacceptable and incendiary language he further exacerbates the problem of everyone losing any insight to his message because we are stunned and amazed at the choice of language.

- President Trump has the ability to communicate from the most Presidential locations. He can provide TV, radio and internet addresses from the oval office, or the White House platform. He can invite media in for press conferences or interviews to discuss his goals and ambitions, plans and pending decisions. Or he can make himself, or his staff, available for press interviews. And while he does some of this, we all spend every day wondering what Tweet he will send over the Twitter social network next. Several million people use Twitter. It is for social exchange. For the President to announce policy positions (such as banning transgenders from military service) or evaluations of key subordinates (such as referring to the attorney general as weak) or military policy (such as opining on the potential retribution toward North Korea) via Twitter belies the nature of the office and his role. His selection of communication venues only serves to make his comments less valuable, rather than more important.

- President Trump neither remains consistent in his communications, nor does he exert loyalty. Changes on health care and denouncing his own staff does not create trust. How are people in the legislature, regulatory agencies or military going to become advocates for his goals when they don’t know if he can be trusted to support their actions, or support them as employees? If you want people to take a different course of action, to let go of the status quo, they have to trust you. Disruptive leaders time and again must state their positions with clarity and demonstrate support for those who do their best to promote the disruptive agenda. They battle fear of the future with clarity around their support for future outcomes those who help describe how the future will be better.

There are times for disruptive leadership. Status quo models become outdated, and outcomes decline as a result. Change offers the opportunity for better outcomes, and helping people migrate to new innovations helps them toward a better future. But implementing innovation and change requires skill at being a disruptive leader. If the process is bungled, you can look like the guy who started a deadly rampage by yelling “fire” when a more reasoned approach would have prevailed. If you don’t follow the best practices of disruptive leadership, you will create chaos.

by Adam Hartung | Jun 12, 2017 | Defend & Extend, Innovation, Leadership

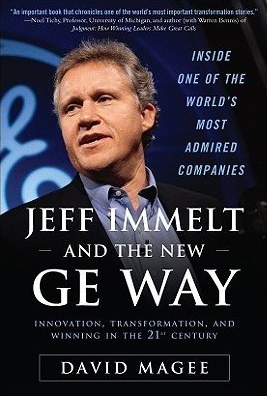

GE Chairman and CEO Jeff Immelt walks off stage after being interviewed during the Washington Ideas Forum at the Harmon Center for the Arts September 28, 2016 in Washington, DC. A proud Republican, Immelt said it would hurt the United States and cripple President Barack Obama — and the next president of the U.S. — not to agree to trade deals like theTrans Pacific Partnership (Photo by Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images)

Readers of this column know I’m not a fan of General Electric’s CEO, Jeffrey Immelt. In May, 2012 I listed CEO Immelt as the 4th worst CEO of a large publicly traded American company. Unfortunately, his continued tenure since then did nothing to help make GE a stronger, or more valuable company. GE’s lead director says this is the culmination of a transition plan first developed in 2011. One can only wonder why it took the board so incredibly long to replace the feckless CEO, and why they allowed GE’s leadership to continue destroying shareholder value.

The longer back you look, the worse Immelt’s performance appears.

Few company analysts can say they’ve followed a company for 3 years. Fewer yet can say 5 years. Nearly none can say a decade. Yet, CEO Immelt was in his job for 16 years – much longer than almost all business analysts or writers have followed GE. Therefore, their lack of long-term memory often leaves them unable to give a proper overview of the company’s fortunes under the long-lived CEO.

I have followed GE closely for almost 35 years. Ever since I graduated from HBS class of 1982 along with Mr. Immelt. Several fellow alumni worked at GE, and a large number of my BCG (Boston Consulting Group) colleagues joined GE in senior positions during the mid-1980s as GE grew exponentially. I have followed several of these alumni as the years passed allowing me to take the “long view” on GE’s performance, during Welch’s leadership and more recently since Mr. Immelt took the top job.

I was very pleased to include a positive case study of GE’s business practices in my book “Create Marketplace Distruption – How to Stay Ahead of the Competition” (Financial Times Press, 2007.) CEO Welch used a number of internal processes to help GE leaders identify disruptive opportunities to change industries – whether markets where GE already competed or new markets. He relentlessly encouraged entering new businesses where GE could bring something new to the game, and he put GE’s money to good use growing revenues, and market cap, enormously. No other CEO in American history made as much value for shareholders as Jack Welch. His leadership pushed GE to the top position in most industries, and his relentless focus on growth helped even rank-and-file employees build million dollar IRAs to go with well funded pension and retiree benefit plans.

GE’s performance could not have changed more dramatically than it has under Mr. Immelt. But there are now a number of apologists who would say GE’s smaller size, and lower valuation, are due to market conditions which were out of Mr. Immelt’s control. They contend CEO Immelt was a good steward of the company during difficult market conditions, and the results of his tenure – notably lower revenues, lower valuation, fewer markets, fewer employees and lower community involvement – are not his fault. They argue he did a good job, all things considered.

Balderdash. Immelt was a terrible CEO

There is an overall reluctance to say bad things about any huge American icon, and its CEO. After all, columnists and analysts who are non-congratulatory don’t usually get called by the company to be consultants, or advisors. Or to be on the board. And publishers of columnists who say negative things about big companies and their execs risk having ad dollars moved to more favorable journals, and often unfriendly relationships with their ad departments and agencies. So it is far easier, and more acceptable, to sugar coat bad strategy, bad leadership and bad results.

But we should move beyond that bias. Mr. Immelt was the CEO of the ONLY company on the Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA) to have been on that list since it was created. He inherited the most successful company at creating shareholder value during the 1980s and 1990s. He surely should be held to the highest of comparative bars.

Those who say CEO Immelt was “set up to fail” are somehow making the case that Immelt would have been more successful if he had inherited a company with a bad brand image, weak history, and inadequate performance. They are rewriting history to say Jack Welch was not a good CEO, and his outsized gains destined GE to do poorly under his successor. That simply defies the facts – and logic.

Looking at the last 16 years of “difficult times,” when GE has struggled under Immelt’s leadership, one should ask “why did so many other companies do so well?” After all, the DJIA has more than doubled. The S&P 500 has almost doubled. The Russell 2000 has almost tripled. Overall, far more companies have gone up in value than down. Why were Immelt’s circumstances so difficult that all of those CEOs did so much better? They dealt with the same financial meltdown, same Great Recession, same increase in regulations, same federal reserve, same government administration – yet they were able to adapt their companies, grow and increase value.

Yes, GE was huge in financial services when Immelt took the reigns, and financial services saw a major crash. But look at the performance of JPMorganChase under CEO Jamie Dimon (also a classmate of Mr. Immelt.) JPM is stronger today than ever, growing and gaining market share and increasing its value to shareholders. Prior to the crash, in spring 2007, GE was trading at $41/share, and now it is $29 – a decline of ~30%. Back then JPM was trading at $53, and now it is $93 – a gain of ~75%. There obviously was a strategy to adapt to market conditions and do well. Just not at GE.

Immelt reacted to market events, poorly, rather than having a prepared, proactive strategy

Let’s not rewrite history. Prior to the banking crash CEO Immelt was more than happy for GE to be in the “easy money” world of finance. Welch had created GE Capital, and Immelt had furthered its growth when lending was easy and profitable. And he supported the enormous growth in GE’s real estate division. When this industry faced the crash, GE faced a near-bankruptcy not because of Welch, but because of Immelt’s leadership during the over 6 years he had been CEO. If there were risks in the system CEO Immelt had ample time to re-arrange the portfolio, reduce lending, offload financial assets and reduce exposure to real estate and mortgages. But Immelt did not do those things. He did not prepare for a reversal in the markets, and he did not prepare the balance sheet for a significant change of events. It was his leadership that left GE exposed.

As GE shares fell to $7 Immelt made a famous deal with Berkshire Hathaway’s CEO Warren Buffet to increase GE’s capital base in order to stave off demise. And this deal saved GE. But this was an extremely sweet deal for Buffett, giving Berkshire very good interest (10%) on the preferred shares and warrants allowing Buffett to buy future shares of GE at a fixed price. Berkshire made a profit, over and above the interest, of $260M on the deal, and overall at least $1.2B. By being prepared Buffett saved GE and made a lot of money. GE’s investors paid the price for a CEO that was unprepared.

But the changes brought about by the crash, and Dodd-Frank, were more than CEO Immelt could manage. Thus GE exited the business selling many assets at fire sale prices. This “turn tale and run” strategy was sold to the public as a way for GE to “focus” on its “core manufacturing business.” Rather, it was a failure of leadership to understand how to manage this business to future success in changed markets. Where Welch’s GE had grasped for disruption as opportunity, Immelt’s GE gasped at disruption and fled, destroying billions in GE value.

Immelt could not grow GE’s businesses, so he divested GE of many.

GE was to be the “industrial internet giant.” GE was to be a leader in the internet-of-things (IoT) where sensors, the cloud and remote devices created greater productivity. And, to be sure, companies like Apple, Google and Samsung have made huge gains in this market. Even small companies, like Nest, were able to jump on this technology shift with new products for the residential market. But name one market where GE is the dominant IoT player. During 16 years the internet and remote services markets have exploded, yet GE is not the market leader. Rather it is barely recognized.

Rather than growing GE with disruptive innovations and visionary products in emerging technology markets, Immelt’s GE was primarily shrinking via divestitures. In dismantling GE Capital he eliminated the lending and real estate operations. After decades as a leader in appliances, that division was sold. Welch built the extremely successful entertainment division around NBC/Universal, which Immelt sold.

The water business that was to be a world leader under Immelt’s vision, likewise sold – and largely to make sure GE could close the deal on selling its oil & gas unit. Even the famed electrical distribution business, going back to the start of GE, is now close to being sold.

And what happened to all this money? Well, about $50B went into share buybacks – which ostensibly would help shareholders. Only it didn’t, because GE is still worth less than when buybacks started. So the money just disappeared. At least Immelt could have paid it to shareholders as a dividend – but then that would not have boosted his bonuses.

GE’s website says Mr. Immelt wanted to create a “simpler, more valuable industrial company.” Mr. Immelt is definitely leaving behind a simpler, much smaller and weaker company. The brand is gone from consumer products, and severely tarnished in commercial products. GE lacks a great product pipeline, and even a strong development pipeline due to the rampant divestitures. When Mr. Flannery takes over as CEO he will not inherit a powerhouse company. He will inherit a company that is shrinking and rudderless, and disconnected from most growth markets with almost no product, technology or brand advantages. And he will report to the Chairman that created this mess, Mr. Immelt.

The most likely outcome is that Mr. Peltz and his firm, Trian Partners, will buy more GE shares and seek directorships on the board. Then, in a move not unlike the deaths of DuPont and Dow, there will be a massive cost cutting effort to bring expenses in-line with the shrunken GE business. R&D will be discontinued, as will product development. Support groups will be shredded. Customer service will be downsized. Then the remaining pieces will be sold off to buyers, or taken public, leaving GE a dismantled piece of history.

While that may work for the capital markets, and some short-term investors will share in the higher valuation, what about the people? People who dedicated their careers to GE, and are pensioners or current employees? What about cities and counties where GE has been a major employer, and civic contributor? What about customers that bought GE industrial products, only to see those products dropped due to low profitability, or little growth opportunity? What about suppliers that invested in developing new technologies or products for GE to take to market? What will happen to the people who once relied on GE as America’s largest diversified industrial company?

These people all have an ax to grind with the very wealthy, and now departing, CEO Immelt. He inherited what may well have been the most successful company on earth. He leaves behind a far weaker company that may not survive.

by Adam Hartung | Apr 21, 2017 | Boards of Directors, Investing, Leadership

When I was young, IBM dominated computing. In the tech world, when comparing platforms, everyone said, “Nobody ever got fired for buying IBM.” IBM was a standout role model for sales success, product leadership and investor returns.

Now, not so much. IBM’s stock fell almost 5% on Wednesday after the company reported “lackluster” results. For the week IBM lost about $20 per share – almost 12%. Quarterly revenue last quarter fell 3%, making 20 consecutive quarters of declining revenue for the once-dominant behemoth and Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA) component.

CEO of IBM Ginni Rometty (Photo by Neilson Barnard/Getty Images for New York Times)

The stock is still up from January 2016 lows of $125, and you might think this pullback is a buying opportunity. But you would be wrong. For long-term investors the stock has fallen from about $194 when CEO Ginni Rometty took control to the recent $160 — a 17.5% decline over five years. And that is after spending $9 billion on payouts (mostly share buybacks) to prop up the stock!

But because of its long-term “growth stall” the odds are almost a certainty things will continue to worsen for IBM.

(c) Adam Hartung and Spark Partners

(c) Adam Hartung and Spark Partners

Growth Stalls are Deadly Accurate Predictors of Future Value Declines

When a company has two consecutive declining quarters of revenue or earnings, or two consecutive quarters of revenue or earnings lower than the previous year, that company is in a “growth stall.” After stalling, 93% of companies will struggle to consistently grow a mere 2%. Seventy percent will lose more than half their market cap.

I made this same

call, to not own IBM, in May 2014. Then IBM had registered a stall on both the quarter-to-quarter metric, and on the year-over-year quarterly metric. IBM was clearly in a “growth stall” and showed no signs of turning around its fortunes. Now IBM has failed to grow quarterly revenue for

five years!Supported by the company PR and investor relations departments, optimists will claim there is reason to think things will improve. For example, in September 2015 IBM executive John Kelly predicted that Watson would be the next “huge engine” for growth. Today the Cognitive Computing segment that is Watson is about the same size it was then. In fact none of the five IBM segments are showing strong growth.

The reason a “growth stall” is such an accurate predictor of future bad results is its ability, in a very simple way, to describe when a company falls out of step with its customers/marketplace. The market went one way — in this case to mobile apps, mobile devices and cloud computing — while the company remained in outdated businesses and launched competitive offerings too late to catch the early market makers. At IBM, Cognitive has not become a big new market, while the historical Business Services and Systems segments keep shrinking, and Cloud Services is simply out-gunned by competitors like Amazon.

Rometty should be replaced by someone from outside IBM.

Meanwhile, the CEO keeps her job and even achieves pay raises! In 2016 IBM’s stock had dropped 36% since Rometty took the CEO position, yet the board of directors payed out the max bonus, leading the LA Times to headline “IBM’s CEO Writes a New Chapter on How To Turn Failure Into Wealth.” Last year the company share price bounced of its lows, but still far below what it was when she took the job, and in 2017 the Board increased her bonus from 2016! And the CEO will be granted a long-term pay incentive of $13.3 million in June (to be paid in 2020).

Like Immelt at GE, Rometty should be fired. If there were an updated list of the “5 Worst CEO’s Who Should Have Already Been Fired,” CEO Rometty surely deserves to be on it. And a new leader needs to implement an entirely new strategy if IBM is ever to regain its lost glory.

IBM’s stock may bounce around quite a bit. It’s shareholder base is very large. And really big investors, like pension funds and mutual funds, are very slow to dump their positions. But, eventually, everyone realizes that a shrinking company is not a value creation company, and they keep selling shares into any sign of strength. Big investors eventually recognize when a Board is unwilling to actually help lead a company, and unwilling to face down a bad CEO and replace her with someone more competently able to turn around a perennial terrible performer. So they start selling before the bottom falls out — like Sears and AT&T after they were removed from the DJIA.

There’s a lot more downside potential for IBM’s valuation.

In IBM’s case, the shares are at about $195 when the first data indicating a growth stall were evident (Q3 2012). They then peaked at $213 in March 2013. And it has been an ugly ride since. he “bounce” in 2016 from $125 to $180 was actually the best selling opportunity since September 2014 (just after I made the call to get out). At $160, IBM is down about 18% since the growth stall started (largely due to share buybacks) and revenues have kept dropping. According to “growth stall” analysis there is a 69% probability IBM’s shares will fall to $85 per share — or less — before the company fails, or starts a true, long-term recovery under new leadership.

by Adam Hartung | Apr 10, 2017 | Leadership, Transportation

Most readers of this column will already know that on Sunday, April 9, 2017 United Airlines forcibly removed a 69-year-old passenger from a flight, over his objections. United employees had Chicago Aviation Police board the plane, grab the passenger (who had a valid boarding pass) and drag him off the plane as if he were a hijacker. In the process the police banged his head on an armrest, leaving him battered and bloodied. When the passenger returned to the plane the police again forcibly manhandled him, restrained him and took him off the plane strapped onto a stretcher.

All so the airline could board a flight attendant that needed to reach the plane’s destination in order to make her next working flight. In other words, United’s front line management chose to not only inconvenience a paying customer, but physically abuse that customer so the airline would maintain its operating crew schedule.

After, the company CEO Oscar Munoz apologized for “re-accomodating” customers. Since about 40,000 people are “re-accomodated” — or bumped from oversold flights — annually, the CEO’s apology covers the 3,675 United customers bumped in 2016. But, he did not apologize for United employees taking action that directly led to the physical abuse of a customer.

Most of us would not believe this story if it were part of a fictional movie. How could it be possible for a front-line employee to think it is acceptable to forcibly eject a paying customer already on the plane?How could it be possible that a CEO would be so uncaring as to not apologize for a clear, horrific lapse in judgement by someone on his management team? Whatever the situation, every action taken by United merely served to make the situation worse. How could a company so large be so mismanaged — from the bottom to the top?

Blame “Operational Excellence”

That is the problem with CEOs, and leadership teams, that focus on “operational excellence” as a strategy. They become so focused on efficiency, cost cutting and business operations that they forget about customers — or anything else. All that matters is keeping the business operating, while trying to keep costs as low as absolutely possible. Management, from bottom to top, is rewarded for operational performance, while all other metrics are ignored. Including customer satisfaction.

In “operationally excellent” companies the focus on low costs is driven by a desire to keep prices low. The perception among management is that customers care only about price, so there is no reason to track anything other than costs. If they keep costs (and prices) low customers will be happy, regardless of anything else in the customer’s experience.

United Has Abused Customers For Years

This is not the first time United has had this kind of problem. In 2009 Canadian musician Dave Carroll became a sensation after producing a series of YouTube videos that chronicled his experience after United baggage handlers destroyed his guitar. The baggage handlers clearly did not care about his guitar. Nor did the gate agents, the baggage department or the customer service department. After many, many calls United personnel simply decided Mr. Caroll’s broken guitar would not be compensated — even though they broke it — and he should just “get over it.”

In 2013, United came in dead last in the Airline Quality Rating. United’s response (as I detailed in a 2013 Forbes column) was simply that “they did not care.” Quite literally, lowering cost was more important that being dead last in customer satisfaction.

In 2016, United fired its CEO after discovering he was bribing government officials to obtain favorable treatment at New Jersey and New York airports. The pressure to lower cost in the “operationally excellent” strategy was so paramount that judgement falters not only at low levels, but all the way up to the CEO.

Operational Excellence Hurt WalMart As Well As United

United isn’t alone in its failures due to operational excellence focus. WalMart has been the victim of bad management judgment for the same reason. Remember in July, 2014 when a WalMart truck driver who had been awake for 24 hours hit a car in New Jersey killing comedian James McNair and seriously injuring comedian Tracy Morgan? That driver had been on the road longer than he should, with insufficient sleep, in his effort to meet operational deadlines – and was charged with aggravated manslaughter, second-degree vehicular homicide and 8 counts of third-degree aggravated assault charges.

This happened just two years after investors learned WalMart was accused of bribing Mexican government officials to keep costs low there — bribery that caused the departure of the WalMart Mexico president, and eventually Walmart’s CEO. In both cases, at the top and at the front line, judgment was impaired by leadership’s focus on operational efficiency.

Unfortunately, too many business leaders put too much energy into operational excellence. They focus on cutting costs, improving operations, and trying to offer low price as the primary reason customers should do business with them. They quickly lose sight of customer needs, wants and wishes as they overly simplify their business’ offering into price. And this leads to bad decision-making all the way from the CEO to the front line manager — who will drive customers away in his effort to meet operational metrics and goals.

Once Locked In Operational Excellence Is A Hard Strategy, And Culture, To Change

United clearly needs a cultural change. But will it make one? Given the CEO’s reaction to this incident, it appears highly unlikely. Locked in to viewing his company operationally, Munoz appears to have lost common sense when it comes to customers – and running the business in a way that can lead to long-term profitability. Herb Kelleher, founder of Southwest Airlines, and Richard Branson, founder of Virgin Airlines, knew there was more to a successful airline than flight schedules and cheap fuel purchases. So far United’s leadership has failed to see the obvious.

by Adam Hartung | Mar 30, 2017 | Boards of Directors, Disruptions, Investing, Leadership

(Photo: CEO of Amazon.com, Inc. Jeff Bezos, TOMMASO BODDI/AFP/Getty Images)

Amazon.com is now worth about the same as Berkshire Hathaway. Amazon has had an amazing run-up in value. The stock is up 17% year to date, and 46% over the last 12 months. By comparison, Berkshire has risen 3.1% this year and Microsoft has risen 5.6% —while the S&P 500 is up 5.8%. Due to this greater value increase, Jeff Bezos has become the second richest man in the world, jumping past Warren Buffett while Bill Gates remains No. 1.

Obviously, it wouldn’t take much of a slip in Amazon, or a jump in Berkshire, to reverse the positions of the companies and their CEOs. But it is important to recognize what is happening when a barely profitable company that sells general merchandise, technology products (Kindles, Fires and Echos) and technology services (AWS) eclipses one of the most revered financial minds and successful investment managers of all time.

Warren Buffett (Photo by Paul Morigi/Getty Images for Fortune/Time Inc)

Berkshire Hathaway was a financial pioneer for the Industrial Era. Warren Buffett bought a down-and-out textile company and created enormous value by turning it into a financial powerhouse. At the time America, and the world, was still in the Industrial Revolution. Making things – manufacturing – was the biggest industry of all. Buffett and his colleagues recognized that capital for these companies was deployed very inefficiently. Often too much capital was invested in poor ways, while insufficient capital was invested in good opportunities. If Berkshire could build a capital base it could deploy that capital into high-return opportunities, and make above-average rates of return.

When Buffett started his magical machine he realized that capital was often in short supply. Companies had to ration capital, unable to build the means of production they desired. Banks were unwilling to lend when they perceived any risk, even when the risk was not that great. Simultaneously investment banks were highly inefficient. The industry was unwilling to support companies prior to going public, often uninterested in taking companies public, and poor at allocating additional capital to the highest return opportunities. By the time you were big enough to use an investment bank you really didn’t need them to raise capital – they just organized the transactions.

This inefficiency in capital allocation meant that an investor with capital could create tremendous gains by deploying it in high return opportunities that often had minimal risk – or at least risk that could be offset with other investments.

Berkshire Hathaway was a big winner at mastering finance during the industrial era. By putting money in the right place, at the right time, tremendous gains could be made. Berkshire didn’t have to be a manufacturer, it could make a higher rate of return by understanding how to deploy capital to industrial companies in a marketplace where capital was rationed. In other words, give people money when they need it and Berkshire could generate outsized returns.

It was a great strategy for supporting companies in the Industrial Age. And a great way to make money when capital was hard to come by.

But the world has changed. Two important things happened First, capital became a lot easier to acquire. Deregulation and a vast expansion of financial services led to a greater willingness to lend by banks, larger secondary markets for bank-originated products that carried risk, the creation of venture capital and private equity firms willing to invest in riskier opportunities, and a dramatic growth in investment banking globally making it far easier to go public and raise equity. Capital became vastly more available, and the cost of capital dropped dramatically.

This made finding opportunities for outsized returns just based on investing considerably more difficult. And thus every year it has become harder for Berkshire Hathaway to find investment opportunities that exceed market rates of return. Berkshire isn’t doing poorly, but it now competes in a world of many competitors who have driven down returns for everyone. Thus, Berkshire’s returns increasingly move toward the market norm.

The Industrial Era is dead — usher in the Information Era. Second, we are no longer in the Industrial Age. Sometime in the 1990s (economic historians will pin it to a specific date eventually) the world transitioned into the Information Age. In the Information Age assets are no longer worth as much as they previously were. Instead, information has become much more valuable. What a business knows about customers, markets and supply chains is worth more than the buildings, machines and trucks that actually make up the physical economy. The value from having information has become much higher than the value of things — or of providing capital to purchase things.

In the Information Era, few companies have mastered the art of information management better than Amazon.com. Amazon doesn’t succeed because it has great retail stores, or great product inventory or even great computers. Amazon’s success is based on knowing things about markets and its customers. Amazon has piles and piles of data, and Amazon monetizes that information into sales.

By studying customer habits, every time they buy something, Amazon has been able to make the company more valuable to customers. Often Amazon is able to tell a customer what they need before they realize they need it. And Amazon is able to predict the flow of new product introductions, and predict sales for manufacturers with great accuracy. Amazon is able to understand what media customers want, and when they’ll want it. Amazon is able to predict a business’ “cloud needs” before that business knows – and predict the customer’s likely future services needs long before the customer knows.

In the Information Age, Amazon is one of the very, very best information companies out there. It knows how to obtain information, analyze those mounds of “big data” to determine and predict needs, then connect customers with things they want to buy. Being great at information means that Amazon, even with its relatively poor current profits, is positioned to capitalize on its intellectual property for years to come. Not without competition. But with a tremendous competitive lead.

So, how is your portfolio allocated? Are you invested in assets, or information? Accumulating assets is a very hard way to make high rates of return. But creating sales, and profits, out of information is far easier today. The relative change in the value of Amazon and Berkshire is telling investors that it is now smarter to be long information rich companies than asset rich companies.

If you’re long GE, GM, 3M and Walmart how well will you do in an economy where information is more valuable than assets? If you don’t own data rich, analytically intensive companies like Amazon, Facebook, Alphabet/Google and Netflix how would you expect to make above-average rates of return?

And where is your business investing? Are you still putting most of your attention on how you allocate capital, in a world where capital is abundant and cheap? Are you focusing your attention on getting the most out of what you know about markets, customers and suppliers, or just making and selling more stuff? Do you invest in projects to give you insights competitors don’t have, or in making more of the products you have — or launching product version X?

And are you being smart about how you manage your most important information tool — your talented employees? Information is worthless without insight. It is critical companies today do all they can to help employees develop insights, and then rapidly deploy those insights to grow sales. If you spend a few hours pouring over expenses to find dimes, consider letting that activity go in order to spend hours brainstorming how to find new markets and new product opportunities that can generate a lot more revenue dollars.

by Adam Hartung | Mar 28, 2017 | In the Rapids, Innovation, Investing, Leadership

(Photo: General Electric CEO Jeffrey Immelt, ERIC PIERMONT/AFP/Getty Images)

General Electric stock had a small pop recently when investors thought CEO Jeffrey Immelt might be pushed out. Obviously more investors hope the CEO leaves than stays. And it appears clear that activist investor Nelson Peltz of Trian Partners thinks it is time for a change in CEO atop the longest running member of the Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA.)

You can’t blame investors, however. Since he took over the top job at General Electric in 2001 (16 years ago) GE’s stock value has dropped 38%. Meanwhile, the DJIA has almost doubled. Over that time, GE has been the greatest drag on the DJIA, otherwise the index would be valued even higher! That is terrible performance — especially as CEO of one of America’s largest companies.

But, after 16 years of Immelt’s leadership, there’s a lot more wrong than just the CEO at General Electric these days. As the JPMorgan Chase analyst Stephen Tusa revealed in his analysis, these days GE is actually overvalued, “cash is weak, margins/share of customer wallet are already at entitlement, the sum of the parts valuation points to a low 20s stock price.” He goes on to share his pessimism in GE’s ability to sell additional businesses, or create cost lowering synergies or tax strategies.

Former Chairman and CEO of General Electric Jack Welch. (AP Photo/Richard Drew)

What went so wrong under Immelt? Go back to 1981. GE installed Jack Welch as its new CEO. Over the next 20 years there wasn’t a business Neutron Jack wouldn’t buy, sell or trade. CEO Welch understood the importance of growth. He bought business after business, in markets far removed from traditional manufacturing, building large positions in media and financial services. He expanded globally, into all developing markets. After businesses were acquired the pressure was relentless to keep growing. All had to be no. 1 or no. 2 in their markets or risk being sold off. It was growth, growth and more growth.

Welch’s focus on growth led to a bigger, more successful GE. Adjusted for splits, GE stock rose from $1.30 per share to $46.75 per share during the 20 year Welch leadership. That is an improvement of 35 times – or 3,500%. And it wasn’t just due to a great overall stock market. Yes, the DJIA grew from 973 to 10,887 — or about 10.1 times. But GE outperformed the DJIA by 3.5 times (350%). Not everything went right in the Welch era, but growth hid all sins — and investors did very, very, very well.

Under Welch, GE was in the rapids of growth. Welch understood that good operating performance was not enough. GE had to grow. Investors needed to see a path to higher revenues in order to believe in long term value creation. Immediate profits were necessary but insufficient to create value, because they could be dissipated quickly by new competitors. So Welch kept the headquarters team busy evaluating opportunities, including making some 600 acquisitions. They invested in things that would grow, whether part of historical GE, or not.

Jeff Immelt as CEO took a decidedly different approach to leadership. During his 16 year leadership GE has become a significantly smaller company. He sold off the plastics, appliances and media businesses — once good growth providers — in the name of “refocusing the company.” Plans currently exist to sell off the electrical distribution/grid business (Industrial Solutions) and water businesses, eliminating another $5 billion in annual revenue. He has dismantled the entire financial services and real estate businesses that created tremendous GE value, because he could not figure out how to operate in a more regulated environment. And cost cutting continues. In the GE Transportation business, which is supposed to remain, plans have been announced to double down on cost cutting, eliminating another 2,900 jobs.

Under Immelt GE has focused on profits. Strategy turned from looking outside, for new growth markets and opportunities, to looking inside for ways to optimize the company via business sales, asset sales, layoffs and other cost cutting. Optimizing the business against some sense of an historical “core” caused nearsighted — and shortsighted — quarterly actions, financial gyrations and transactions rather than building a sustainable, growing revenue stream. Under Immelt sales did not just stagnate, sales actually declined while leadership pursued higher margins.

By focusing on the “core” GE business (as defined by Immelt) and pursuing short term profit maximization, leadership significantly damaged GE. Nobody would have ever imagined an activist investor taking a position in Welch’s GE in an effort to restructure the company. Its sales growth was so good, its prospects so bright, that its P/E (price to earnings) multiple kept it out of activist range.

But now the vultures see the opportunity to do an even bigger, better job of whacking up GE — of tearing it into small bits while killing off all R&D and innovation — like they did at DuPont. Over 16 years Immelt has weakened GE’s business — what was the most omnipresent industrial company in America, if not the world – to the point that it can be attacked by outsiders ready to chop it up and sell it off in pieces to make a quick buck.

Thomas Edison, one of the world’s great inventors, innovators and founder of GE, would be appalled. That GE needs now, more than ever, is a leader who understands you cannot save your way to prosperity, you have to invest in growth to create future value and increase your equity valuation.

In May, 2012 (five years ago) I warned investors that Immelt was the wrong CEO. I listed him as the fourth worst CEO of a publicly traded company in America. While he steered GE out of trouble during the financial crisis, he also simply steered the company in circles as it used up its resources. Then was the time to change CEOs, and put in place someone with the fortitude to develop a growth strategy that would leverage the resources, and brand, of GE. But, instead, Immelt remained in place, and GE became a lot smaller, and weaker.

At this point, it is probably too late to save GE. By losing sight of the need to grow, and instead focusing on optimizing the old business while selling assets to raise cash for reorganizations, Immelt has destroyed what was once a great innovation engine. Now that the activists have GE in their sites it is unlikely they will let it ever return to the company it once was – creating whole new markets by developing new technologies that people never before imagined. The future looks a lot more like figuring out how to maximize the value of each piece of meat as it’s carved off the GE carcass.

by Adam Hartung | Mar 10, 2017 | Books, Defend & Extend, Employment, Leadership

Harvard Business Review Press just published an insightful new book by two senior partners at Bain & Company, one of the world’s three leading strategy consulting firms, entitled Time Talent Energy. The book’s great insight is that companies utilize a plethora of tools to manage money and financials to the nth degree, but that approach is less successful than putting a greater focus on managing employee time, talent and energy.

Harvard Business Review Press

Harvard Business Review Press

Time Talent Energy jacket cover

While managing financials is required in the modern organization, it is insufficient for success. Mankins and Garton discovered that organizations which focus more heavily on managing how employees spend their time and how they thoughtfully place people in their roles, create companies where employees are inspired and 40% more productive than their competition. And this pays off, with profit margins which are 30-50% higher than their industry average. The improvement is so great from focusing on employees that in today’s low cost and easily accessible capital world it is better to waste some cash in the process of better managing time and talent.

In most companies 25% of all productive time is wasted and can reach as high as 40% in complex organizations. Think of all the emails, texts, voice mails and meetings that absorb vast amounts of time. Yet, as the authors are fond of pointing out, nobody can create a 25 hour day. So if you can recapture that time, productivity will soar. The results are far greater than squeezing another 1% (or even 10%) out of your cost structure. If instead of spending so much time managing costs we spent more time eliminating complexity and unneeded tasks, competitiveness will soar.

Some people think that the best companies hire better people. Surprisingly, this is not true. About 15-16% of employees in every company are “A” players. But most companies squander this talent by spreading it around the organization. To achieve higher productivity and greater success, leading companies cluster their “A” players into teams focused on the most critical, important parts of the business. Thus, the best talent is working side-by-side on the most important challenges which can lead to the greatest gains. This talent clustering energizes the best workers, increasing productivity by 44%. But more than that, as the culture is inspired from building on its own gains productivity soars as much as 125%.

But in most organizations the focus still remains on finance. The CFO is frequently the second most powerful individual, behind only the CEO. The head of Human Resources (Chief Human Resources Officer — CHRO) rarely has the clout of a CFO. And the CFO job is seen as the route to CEO — far more CFOs than CHROs become CEOs. Simultaneously, organizations spend exorbitantly on financial control tools, such as ERP (Enterprise Resource Planning) from companies like Oracle and SAP — while very few have any kind of tool set for effectively managing employee time or talent deployment. The authors conclude it is apparent business leaders have significantly overshot on managing financial resources, while allowing their organization to be woefully incapable of managing its human resources.

I had the opportunity to interview Michael Mankins to obtain some additional insight about managing time, talent and energy:

Adam Hartung: Do businesses need to lessen the CFO role, and heighten the CHRO role?

Michael Mankins: The reality is that most human resource decisions, those that determine how people spend their time, and how talent is deployed, are made by line managers. Made within the bowels of the organization, with little more than senior leadership guidelines. There needs to be significantly more involvement by senior leadership in collecting and reviewing data on critical skills for the organization, “A” player performance and leadership development. If as much time was spent by senior leadership teams discussing human resources as spent on budgets there would be a tremendous improvement in productivity.

The CFO and CHRO should definitely be peers. To do that requires a cultural change from being an organization focused on preserving the status quo, reducing mistakes and keeping leadership out of jail to one that is far more future oriented. This can be done and in the book we highlight companies such as ABInBev, Ford, Nordstrom, Starbucks, IKEA, Netflix and others who have accomplished this.

Hartung: Companies spent enormous sums installing ERP systems and they spend a lot to maintain them. Yet, from reading your book it seems like this may have been misguided.

Mankins: All companies need to be able to change their business model as markets shift. ERP frequently creates a wiring that makes it hard to change with the competitive landscape, or as changes in capability are required. ERP locks in the business model at a point in time — but great performers develop ways to adapt.

All companies need a great general ledger. ERP goes far beyond the general ledger and in doing so can make a company too inflexible for today’s rate of change. There needs to be a flexible ERP system —which just doesn’t seem to exist right now. The ERP market seems ripe for a marketplace disrupter!

Simultaneously there aren’t any great tools out there for collecting data that can help a company reduce complexity and eliminate time wasters. Nor are there great tools for managing the performance of “A” players. The top performing companies do create a discipline around these tasks, collecting and analyzing data. Many companies would be helped by a tool that would do for time and talent management what we’ve done for financial management.

Hartung: You demonstrate that clustering “A” players creates dramatic improvement in productivity and company performance. Do great companies focus these clusters on improving the company as it is, or looking for the next “big thing?”

Mankins: We discovered that by and large the greatest gains come from focusing on the latter. Almost all MBA programs are maniacal about training managers to improve the existing business. For many years corporate planning systems have focused almost entirely on improving the operating model. The result is that in many, many industries leadership has almost no hope of improving operating margins by even 1%. There simply is nothing left to improve which can achieve significant results.

Simultaneously, 1% growth has a far, far greater return on investment than 1% operating margin improvement. So if companies focus their best talent on breakthroughs, in whole new ways of running the business, or creating new markets, the results are significantly greater.

Hartung: Many companies have clustered their top performers into “all star teams.” But this has been met by demotivation of employees not on these teams – feeling like “also rans” or “bench warmers.” And often there is a compensation difference between the all-star team members and others that is demotivating. How do leaders manage this conundrum?

Mankins: If this demotivation is driven by internal competitiveness — by ambition to move up the organization — there is a culture problem. Everyone is not on the same page about company needs and the talent to address those needs. Internal competitiveness should be addressed so everyone wants the company to succeed, so everyone individually can succeed. Rewards, compensation and non-compensation, need to be geared for groups to be motivated, not just individuals.

In the organization, leadership should work hard to make sure everyone knows they are important. There should be an effort to reward the “supporting cast” and not just the main characters. It is true that in today’s world many people have an exaggerated view of their own performance. We address this in the book with recommendations for how to give people feedback so they know the reality of their role and their performance in order to grow and do better. Today most companies have a very poorly performing review and training process, because they tie it to the compensation cycle thus limiting feedback to once per year and, unfortunately, doing feedback at the same time (often the same meeting) as compensation and bonus decisions. Addressing the performance feedback process can go a long way to avoid the demotivation problem.

Hartung: How do companies find “A” players?

Mankins: Search firms are the antithesis of finding “A” players. Their approach, their process, is not designed to deliver “A” candidates. To build a good group of “A” players requires the CEO, CHRO and senior leadership team understand what constitutes an “A” player in their organization. Then they can use the entire organization to seek out people with this behavioral signature in order to recruit them.

It is unfortunate that most company HR processes would not recognize an “A” player if one submitted a resume and would not hire one if they arrived for an interview. Most current processes focus too much on relationships (who candidates know,) narrow skills and prior specific experiences and not enough on what is needed for future success. And hiring decisions are often made by the wrong people; people too low in the organization and people who don’t know the desired behavioral signature. Google is one role model for knowing how to find and develop “A” players.

Unfortunately there is enormous ageism in hiring today. Especially in technology. Employers lack awareness of the value of generalizable experience they can bring into their company. The search for very specific experiences often leads to a very limited list of candidates with narrow experience and too often they do not perform at the “A” level when placed in the context of the new company and new competitive market requirements. Looking more broadly at candidates with great experience, even if not seemingly directly applicable (including candidates in their 50s and 60s) could lead to far greater success.

by Adam Hartung | Feb 22, 2017 | Immigration, Leadership, Politics

(Photo by Olivier Douliery-Pool/Getty Images)

There is a lot of excitement about President Donald Trump’s planned new executive order on immigration. Before the order is even public, the press has been grilling White House Press Secretary Sean Spicer about its contents. People are preparing to object before the document is even read.

Given that we know the order deals only with immigrants from seven countries, and that people from those countries do not constitute anywhere near a meaningful minority of immigrants (or tourists), one could make a case that in and of itself the executive order should not receive anywhere near this much attention.

But simultaneously, President Trump’s secretary of state and secretary of homeland security are visiting Mexico on Thursday — which is creating its own a firestorm of media coverage. The Mexican government leadership has already come out swinging, before the meeting, saying that the Trump administration policies are unacceptable. Not only is the wall construction unacceptable, but plans to deport illegal immigrants to Mexico — including illegal immigrants that are not Mexican — will not be tolerated. They want to know why should Mexico be forced to take Guatemalans, Hondurans and other non-Mexicans?

All of this controversy is being driven by the U.S. leadership, the president and his cabinet, failing to offer a clear policy on immigration. These executive orders, impending demands and vitriolic statements from the administration are like rifle shots aimed at something. But because nobody has a clue what the administrations real immigration policy is, it is impossible to understand the context from which these shots are fired. Nobody really knows what these shots are aimed at achieving.

So everyone, including the media, is left guessing, “what is the target of these actions? What is the overall goal? What is the administration’s immigration policy into which these actions fit?”

The administration says these actions are driven by “national security.” But it is impossible to understand that claim lacking any context. How are these specific actions supposed to improve national security, when every day people come to the U.S. from Europe and Asia with Muslim backgrounds and training? People cross the Canadian border daily who started in another country, yet they are not seen as the same threats as those who cross the southern border — why not?

Thus, each rifle shot looks an awful lot like an attack against the narrow interest being targeted — specifically middle eastern Muslims and Mexicans. And a lot of people are left scratching their heads as to why these folks are being attacked, other than they are simply easy targets for a part of the U.S. population that is horribly xenophobic.

Everyone — and I literally mean everyone — knows that America is a nation of immigrants. Last Labor Day I wrote about the benefits America has enjoyed by opening its doors to immigration. Recently Ryan McCready of Venngage put together a detailed infographic describing how over half of America’s billion dollar start-ups were founded by immigrants, how 33,000 permanent jobs were created by immigrants, how 76% of patents from top universities were filed by immigrants, and how 100% of America’s 2016 Nobel Prize recipients were immigrants. Nobody really doubts that immigrants have been good for America.