by Adam Hartung | Oct 25, 2015 | Current Affairs, Defend & Extend, Food and Drink, In the Swamp, In the Whirlpool, Leadership, Web/Tech

This week McDonald’s and Microsoft both reported earnings that were higher than analysts expected. After these surprise announcements, the equities of both companies had big jumps. But, unfortunately, both companies are in a Growth Stall and unlikely to sustain higher valuations.

McDonald’s profits rose 23%. But revenues were down 5.3%. Leadership touted a higher same store sales number, but that is completely misleading.

McDonald’s leadership has undertaken a back to basics program. This has been used to eliminate menu items and close “underperforming stores.” With fewer stores, loyal customers were forced to eat in nearby stores – something not hard to do given the proliferation of McDonald’s sites. But some customers will go to competitors. By cutting stores and products from the menu McDonald’s may lower cost, but it also lowers the available revenue capacity. This means that stores open a year or longer could increase revenue, even though total revenues are going down.

Profits can go up for a raft of reasons having nothing to do with long-term growth and sustainability. Changing accounting for depreciation, inventory, real estate holdings, revenue recognition, new product launches, product cancellations, marketing investments — the list is endless. Further, charges in a previous quarter (or previous year) could have brought forward costs into an earlier report, making the comparative quarter look worse while making the current quarter look better.

Confusing? That’s why accounting changes are often called “financial machinations.” Lots of moving numbers around, but not necessarily indicating the direction of the business.

McDonald’s asked its “core” customers what they wanted, and based on their responses began offering all-day breakfast. Interpretation – because they can’t attract new customers, McDonald’s wants to obtain more revenue from existing customers by selling them more of an existing product; specifically breakfast items later in the day.

Sounds smart, but in reality McDonald’s is admitting it is not finding new ways to grow its customer base, or sales. The old products weren’t bringing in new customers, and new products weren’t either. As customer counts are declining, leadership is trying to pull more money out of its declining “core.” This can work short-term, but not long-term. Long-term growth requires expanding the sales base with new products and new customers.

Perhaps there is future value in spinning off McDonald’s real estate holdings in a REIT. At best this would be a one-time value improvement for investors, at the cost of another long-term revenue stream. (Sort of like Chicago selling all its future parking meter revenues for a one-time payment to bail out its bankrupt school system.) But if we look at the Sears Holdings REIT spin-off, which ostensibly was going to create enormous value for investors, we can see there were serious limits on the effectiveness of that tactic as well.

MIcrosoft also beat analysts quarterly earnings estimate. But it’s profits were up a mere 2%. And revenues declined 12% versus a year ago – proving its Growth Stall continues as well. Although leadership trumpeted an increase in cloud-based revenue, that was only an 8% improvement and obviously not enough to offset significant weakness in other markets:

It is a struggle to see the good news here. Office 365 revenues were up, but they are cannibalizing traditional Office revenues – and not fast enough to replace customers being lost to competitive products like Google OfficeSuite, etc.

Azure sales were up, but not fast enough to replace declining Windows sales. Further, Azure competes with Amazon AWS, which had remarkable results in the latest quarter. After adding 530 new features, AWS sales increased 15% vs. the previous quarter, and 78% versus the previous year. Margins also increased from 21.4% to 25% over the last year. Azure is in a growth market, but it faces very stiff competition from market leader Amazon.

We build our companies, jobs and lives around successful products and services. We want these providers to succeed because it makes our lives much easier. We don’t like to hear about large market leaders losing their strength, because it signals potentially difficult change. We want these companies to improve, and we will clutch at any sign of improvement.

As investors we behave similarly. We were told large companies have vast customer bases, strong asset bases, well known brands, high switching costs, deep pockets – all things Michael Porter told us in the 1980s created “moats” protecting the business, keeping it protected from market shifts that could hurt sales and profits. As investors we want to believe that even though the giant company may slip, it won’t fall. Time and size is on its side we choose to believe, so we should simply “hang on” and “ride it out.” In the future, the company will do better and value will rise.

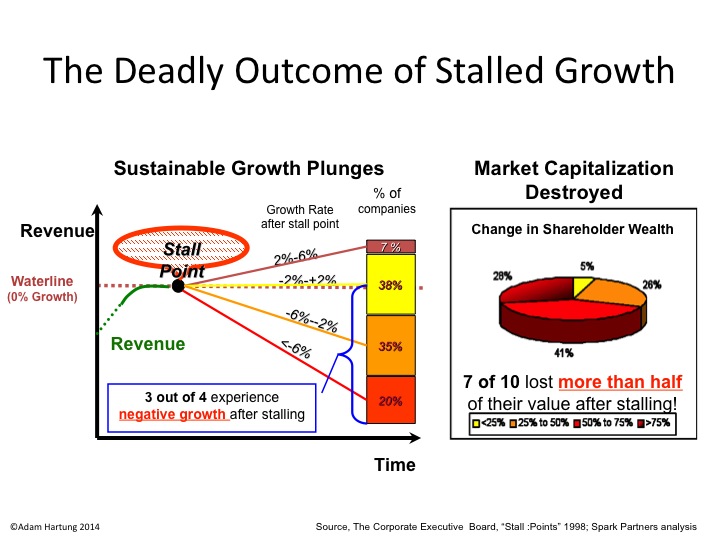

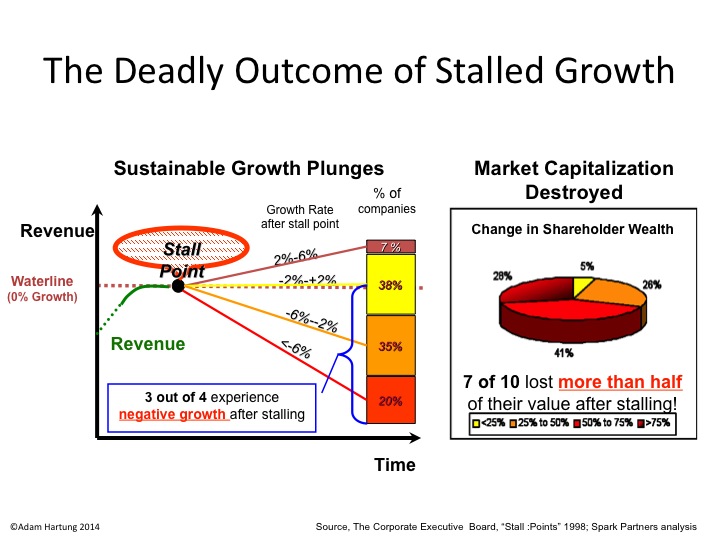

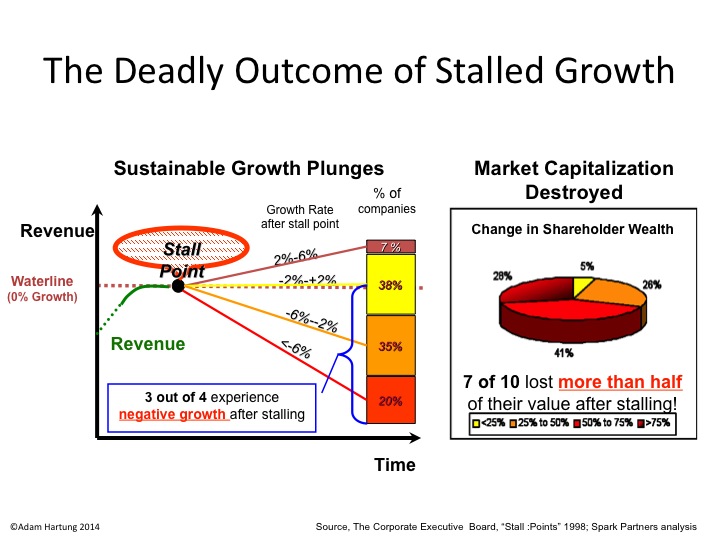

As a result we see that Growth Stall companies show a common valuation pattern. After achieving high valuation, their equity value stagnates. Then, hopes for a turn-around and recovery to new growth is stimulated by a few pieces of good news and the value jumps again. Only after a few years the short-term tactics are used up and the underlying business weakness is fully exposed. Then value crumbles, frequently faster than remaining investors anticipated.

McDonald’s valuation rose from $62/share in 2008 to reach record $100/share highs in 2011. But valuation then stagnated. It is only this last jump that has caused it to reach new highs. But realize, this is on a smaller number of stores, fewer products and declining revenues. These are not factors justifying sustainable value improvement.

Microsoft traded around $25/share from March, 2003 through November, 2011 – 8.5 years. When the CEO was changed value jumped to $48/share by October, 2014. After dipping, now, a year later Microsoft stock is again reaching that previous valuation ($50/share). Microsoft is now valued where it was in December, 2002 (which is half its all-time high.)

The jump in value of McDonald’s and Microsoft happened on short-term news regarding beating analysts earnings expectations for one quarter. The underlying businesses, however, are still suffering declining revenue. They remain in Growth Stalls, and the odds are overwhelming that their values will decline, rather than continue increasing.

by Adam Hartung | Jul 25, 2015 | Current Affairs, In the Whirlpool, Leadership

This week an important event happened on Wall Street. The value of Amazon (~$248B) exceeded the value of Walmart (~$233B.) Given that Walmart is world’s largest retailer, it is pretty amazing that a company launched as an on-line book seller by a former banker only 21 years ago could now exceed what has long been retailing’s juggernaut.

WalMart redefined retail. Prior to Sam Walton’s dynasty retailing was an industry of department stores and independent retailers. Retailing was a lot of small operators, primarily highly regional. Most retailers specialized, and shoppers would visit several stores to obtain things they needed.

But WalMart changed that. Sam Walton had a vision of consolidating products into larger stores, and opening these larger stores in every town across America. He set out to create scale advantages in purchasing everything from goods for resale to materials for store construction. And with those advantages he offered customers lower prices, to lure them away from the small retailers they formerly visited.

And customers were lured. Today there are very few independent retailers. WalMart has ~$488B in annual revenues. That is more than 4 times the size of #2 in USA CostCo, or #1 in France (#3 in world) Carrefour, or #1 in Germany (#4 in world) Schwarz, or #1 in U.K. (#5 in world) Tesco. Walmart directly employes ~.5% of the entire USA population (about 1 in every 200 people work for Walmart.) And it is a given that nobody living in America is unaware of Walmart, and very, very few have never shopped there.

But, Walmart has stopped growing. Since 2011, its revenues have grown unevenly, and on average less than 4%/year. Worse, it’s profits have grown only 1%/year. Walmart generates ~$220,000 revenue/employee, while Costco achieves ~$595,000. Thus its need to keep wages and benefits low, and chronically hammer on suppliers for lower prices as it strives to improve margins.

And worse, the market is shifting away from WalMart’s huge, plentiful stores toward on-line shopping. And this could have devastating consequences for WalMart, due to what economists call “marginal economics.”

And worse, the market is shifting away from WalMart’s huge, plentiful stores toward on-line shopping. And this could have devastating consequences for WalMart, due to what economists call “marginal economics.”

As a retailer, Walmart spends 75 cents out of every $1 revenue on the stuff it sells (cost of goods sold.) That leaves it a gross margin of 25 cents – or 25%. But, all those stores, distribution centers and trucks create a huge fixed cost, representing 20% of revenue. Thus, the net profit margin before taxes is a mere 5% (Walmart today makes about 5 cents on every $1 revenue.)

But, as sales go from brick-and-mortar to on-line, this threatens that revenue base. At Sears, for example, revenues per store have been declining for over 4 years. Suppose that starts to happen at Walmart; a slow decline in revenues. If revenues drop by 10% then every $100 of revenue shrinks to $90. And the gross margin (25%) declines to $22.50. But those pesky store costs remain stubbornly fixed at $20. Now profits to $2.50 – a 50% decline from what they were before.

A relatively small decline in revenue (10%) has a 5x impact on the bottom line (50% decline.) The “marginal revenue”, is that last 10%. What the company achieves “on the margin.” It has enormous impact on profits. And now you know why retailers are open 7 days a week, and 18 to 24 hours per day. They all desperately want those last few “marginal revenues” because they are what makes – or breaks – their profitability.

All those scale advantages Sam Walton created go into reverse if revenues decline. Now the big centralized purchasing, the huge distribution centers, and all those big stores suddenly become a cost Walmart cannot avoid. Without growing revenues, Walmart, like has happened at Sears, could go into a terrible profit tailspin.

And that is what Amazon is trying to do. Amazon is changing the way Americans shop. From stores to on-line. And the key to understanding why this is deadly to Walmart and other big traditional retailers is understanding that all Amazon (and its brethren on line) need to do is chip away at a few percentage points of the market. They don’t have to obtain half of retail. By stealing just 5-10% they put many retailers, they ones who are weak, right out of business. Like Radio Shack and Circuit City. And they suck the profits out of others like Sears and Best Buy. And they pose a serious threat to WalMart.

And Amazon is succeeding. It has grown at almost 30%/year since 2010. That growth has not been due to market growth, it has been created by stealing sales from traditional retailers. And Amazon achieves $621,000 revenue per employee, while having a far less fixed cost footprint.

What the marketplace looks for is that point at which the shift to on-line is dramatic enough, when on-line retailers have enough share, that suddenly the fixed cost heavy traditional retail business model is no longer supportable. When brick-and-mortar retailers lose just enough share that their profits start the big slide backward toward losses. Simultaneously, the profits of on-line retailers will start to gain significant upward momentum.

And this week, the marketplace started saying that time could be quite near. Amazon had a small profit, surprising many analysts. It’s revenues are now almost as big as Costco, Tesco – and bigger than Target and Home Depot. If it’s pace of growth continues, then the value which was once captured in Walmart stock will shift, along with the marketplace, to Amazon.

In May, 2010 Apple’s value eclipsed Microsoft. Five years later, Apple is now worth double Microsoft – even though its earnings multiple (stock Price/Earnings) is only half (AAPL P/E = 14.4, MSFT = 31.) And Apple’s revenues are double Microsoft’s. And Apple’s revenues/employee are $2.4million, 3 times Microsoft’s $731k.

While Microsoft has about doubled in value since the valuation pinnacle transferred to Apple, investors would have done better holding Apple stock as it has more than tripled. And, again, if the multiple equalizes between the companies (Apple’s goes up, or Microsoft’s goes down,) Apple investors will be 6 times better off than Microsoft’s.

Market shifts are a bit like earthquakes. Lots of pressure builds up over a long time. There are small tremors, but for the most part nobody notices much change. The land may actually have risen or fallen a few feet, but it is not noticeable due to small changes over a long time. But then, things pop. And the world quickly changes.

This week investors started telling us that the time for big change could be happening very soon in retail. And if it does, Walmart’s size will be more of a disadvantage than benefit.

by Adam Hartung | Jul 8, 2015 | Current Affairs, Defend & Extend, In the Whirlpool, Leadership, Lock-in, Web/Tech

Microsoft announced today it was going to shut down the Nokia phone unit, take a $7.6B write-off (more than the $7.2B they paid for it,) and lay off another 7,800 employees. That makes the layoffs since CEO Nadella took the reigns almost 26,000. Finding any good news in this announcement is a very difficult task.

Unfortunately, since taking over as Microsoft’s #1 leader, Mr. Nadella has been remarkably predictable. Like his peer CEOs who take on the new role, he has slashed and burned employment, shut down at least one big business, taken massive write-offs, and undertaken at least one wildly overpriced acquisition (Minecraft) that is supposed to be a game changer for the company. He apparently picked up the “Turnaround CEO Playbook” after receiving the job and set out on the big tasks!

Unfortunately, since taking over as Microsoft’s #1 leader, Mr. Nadella has been remarkably predictable. Like his peer CEOs who take on the new role, he has slashed and burned employment, shut down at least one big business, taken massive write-offs, and undertaken at least one wildly overpriced acquisition (Minecraft) that is supposed to be a game changer for the company. He apparently picked up the “Turnaround CEO Playbook” after receiving the job and set out on the big tasks!

Yet he still has not put forward a strategy that should encourage investors, employees, customers or suppliers that the company will remain relevant long-term. Amidst all these big tactical actions, it is completely unclear what the strategy is to remain a viable company as customers move, quickly and in droves, to mobile devices using competitive products.

I predicted here in this blog the week Steve Ballmer announced the acquisition of Nokia in September, 2013 that it was “a $7.2B mistake.” I was off, because in addition to all the losses and restructuring costs Microsoft endured the last 7 quarters, the write off is $7.6B. Oops.

Why was I so sure it would be a mistake? Because between 2011 and 2013 Nokia had already lost half its market share. CEO Elop, who was previously a Microsoft senior executive, had committed Nokia completely to Windows phones, and the results were already catastrophic. Changing ownership was not going to change the trajectory of Nokia sales.

Microsoft had failed to build any sort of developer community for Windows 8 mobile. Developers need people holding devices to buy their software. Nokia had less than 5% share. Why would any developer build an app for a Windows phone, when almost the entire market was iOS or Android? In fact, it was clear that developing rev 2, 3, and 4 of an app for the major platforms was far more valuable than even bothering to port an app into Windows 8.

Nokia and Windows 8 had the worst kind of tortuous whirlpool – no users, so no developers, and without new (and actually unique) software there was nothing to attract new users. Microsoft mobile simply wasn’t even in the game – and had no hope of winning. It was already clear in June, 2012 that the new Windows tablet – Surface – was being launched with a distinct lack of apps to challenge incumbents Apple and Samsung.

By January, 2013 it was also clear that Microsoft was in a huge amount of trouble. Where just a few years before there were 50 Microsoft-based machines sold for every competitive machine, by 2013 that had shifted to 2 for 1. People were not buying new PCs, but they were buying mobile devices by the shipload – literally. And there was no doubt that Windows 8 had missed the mobile market. Trying too hard to be the old Windows while trying to be something new made the product something few wanted – and certainly not a game changer.

A year ago I wrote that Microsoft has to win the war for developers, or nothing else matters. When everyone used a PC it seemed that all developers were writing applications for PCs. But the world shifted. PC developers still existed, but they were not able to grow sales. The developers making all the money were the ones writing for iOS and Android. The growth was all in mobile, and Microsoft had nothing in the game. Meanwhile, Apple and IBM were joining forces to further displace laptops with iPads in commercial/enterprise uses.

Then we heard Windows 10 would change all of that. And flocks of people wrote me that a hybrid machine, both PC and tablet, was the tool everyone wanted. Only we continue to see that the market is wildly indifferent to Windows 10 and hybrids.

Imagine you write with a fountain pen – as most people did 70 years ago. Then one day you are given a ball point pen. This is far easier to use, and accomplishes most of what you want. No, it won’t make the florid lines and majestic sweeps of a fountain pen, but wow it is a whole lot easier and a darn site cheaper. So you keep the fountain pen for some uses, but mostly start using the ball point pen.

Then the fountain pen manufacturer says “hey, I have a contraption that is a ball point pen, sort of, and a fountain pen, sort of, combined. It’s the best of all worlds.” You would likely look at it, but say “why would I want that. I have a fountain pen for when I need it. And for 90% of the stuff I write the ball point pen is great.”

That’s the problem with hybrids of anything – and the hybrid tablet is no different. The entrenched sellers of old technology always think a hybrid is a good idea. But once customers try the new thing, all they want are advancements to the new thing. (Just look at the interest in Tesla cars compared to the stagnant sales of hybrid autos.)

And we’re up to Surface 3 now. When I pointed out in January, 2013 that the markets were rapidly moving away from Microsoft I predicted Surface and Surface Pro would never be important products. Reader outcry at that time from Microsoft devotees was so great that Forbes editors called me on the carpet and told me I lacked the data to make such a bold prediction. But I stuck by my guns, we changed some language so it was less blunt, and the article ran.

Two and a half years later and we’re up to rev number Surface 3. And still, almost nobody is using the product. Less than 5% market share. Right again. It wasn’t a technology prediction, it was a market prediction. Lacking app developers, and a unique use, the competition was, and remains, simply too far out front.

Windows 10 is, unfortunately, a very expensive launch. And to get people to use it Microsoft is giving it away for free. The hope is then users will hook onto the cloud-based Office 365 and Microsoft’s Azure cloud services. But this is still trying to milk the same old cow. This approach relies on people being completely unwilling to give up using Windows and/or Office. And we see every day that millions of people are finding alternatives they like just fine, thank you very much.

Gamers hated me when I recommended Microsoft should give (for free) xBox to Nintendo. Unfortunately, I learned few gamers know much about P&Ls. They all assumed Microsoft made a fortune in gaming. But anyone who’s ever looked at Microsoft’s financial filings knows that the Entertainment Division, including xBox, has been a giant money-sucking hole. If they gave it away it would save money, and possibly help leadership figure out a strategy for profitable growth.

Unfortunately, Microsoft bought Minecraft, in effect “doubling down” on the bet. But regardless of how well anyone likes the products, Microsoft is not making money. Gaming is a bloody war where Sony and Microsoft keep battling, and keep losing billions of dollars. The odds of ever earning back the $2.5B spent on Minecraft is remote.

The greater likelihood is that as write offs continue to eat away at profits, and as markets continue evolving toward mobile products offered by competitors hurting “core” Microsoft sales, CEO Nadella will eventually have to give up on gaming and undertake another Nokia-like event.

All investors risk looking at current events to drive decision-making. When Ballmer was sacked and Nadella given the CEO job the stock jumped on euphoria. But the last 18 months have shown just how bad things are for Microsoft. It is a near monopolist in a market that is shrinking. And so far Mr. Nadella has failed to define a strategy that will make Microsoft into a company that does more than try to milk its heritage.

I said the giant retailer Sears Holdings would be a big loser the day Ed Lampert took control of the company. But hope sprung eternal, and investors jumped on the Sears bandwagon, believing a new CEO would magically improve a worn out, locked-in company. The stock went up for over 2 years. But, eventually, it became clear that Sears is irrelevant and the share price increase was unjustified. And the stock tanked.

Microsoft looks much the same. The actions we see are attempts to defend & extend a gloried history. But they don’t add up to a strategy to compete for the future. HoloLens will not be a product capable of replacing Windows plus Office revenues. If developers are attracted to it enough to start writing apps. Cortana is cool, but it is not first. And competitive products have so much greater usage that developer learning curve gains are wildly faster. These products are not game changers. They don’t solve large, unmet needs.

And employees see this. As I wrote in my last column, it is valuable to listen to employees. As the bloom fell off the rose, and Nadella started laying people off while freezing pay, employee support of him declined dramatically. And employee faith in leadership is far lower than at competitors Apple and Google.

As long as Microsoft keeps playing catch up, we should expect more layoffs, cost cutting and asset sales. And attempts at more “hail Mary” acquisitions intended to change the company. All of which will do nothing to grow customers, provide better jobs for employees, create value for investors or greater revenue opportunities for suppliers.

by Adam Hartung | Jun 30, 2015 | Current Affairs, In the Swamp, In the Whirlpool, Leadership

24×7 Wall Street just released its fourth annual analysis of the worst companies to work for in America. By looking across all four reports it is possible to identify likely problems which will be valuable for investors, employees (current and prospective,) suppliers and communities to know.

Trend 1- Low minimum wages & “Wage gap” issues remain a big deal

Trend 1- Low minimum wages & “Wage gap” issues remain a big deal

The lists are dominated by retailers. Of the 30 unique companies identified, exactly half (15) were retailers. A handful were on the list 2 or more years. Consistently these employees complained about low wages.

By paying minimum wage, and often refusing to hire employees full time, the companies keep costs of brick and mortar store operations lower.

However, this takes a toll on employee morale as overall pay does not meet minimum living standards. Further employees feel heavily overworked and stressed, while having no job security. Often this leads to employee unhappiness with senior management, frequently offering low evaluations of the CEO – who makes 1,000 times their annual earnings.

As employees fight for higher wages, and a reduction in the “wage gap,” it will apply pressure to the sustainability of these retailers who rely on very low pay to maintain (or enhance) profits. The trend to a higher minimum wage will challenge profit growth – or maintenance – in these companies.

Trend 2 – Employees often “see change coming” and become negatively vocal

Jos. A Banks jumped onto the list as #4 in 2013. Just before a major shake-up and being acquired by Men’s Wearhouse. Family Dollar also appeared on the list in 2014 (#9,) only to be embroiled in a takeover battle with Dollar General, and finally aquired by Dollar Tree within 7 months. Office Max appeared on the list (#5) in 2012, and was acquired by Office Depot 8 months later. And, of course, Radio Shack made the list in 2012 (#3,) 2013 (#5) and 2014 (#11) only to file bankruptcy in 2015.

Employees can see when something bad is impending, likely jeopardizing their livelihoods, and start talking about it.

Similarly, growing internet threats are often picked-up by employees. hh Gregg employees started complaining loudly in 2014 (#8) as their 100% commission compensation became threatened by a growing Amazon.com. And that same year Books-A-Million was #1 on the list, as part time staffers saw the same advancing Amazon. And in 2012 Game Stop (#10) employees could see how the advancing Netflix and Hulu threatened the “core business” and started to light up the complaint section.

Trend 3 – Ignoring employee unhappiness while focusing on earnings can portend a disaster

Sears and KMart (collectively Sears Holdings) made the list in 3 of the 4 years. The stock was $66 in June, 2011, and $55 in 6/12 when it made #6. By 6/13 it had declined to $39, and made the list at #7. Starting 6/14 the stock was reasonably flat, and missed the list. But then in 6/17 the stock fell to 27 and reappeared twice – as both Sears and KMart.

Employees have consistently expressed their dismay with CEO Ed Lampert, and 80% actively dislike his leadership. After the Radio Shack experience, there is ample reason to listen more to these employees than the CEO who keeps promising a turnaround – amidst a long string of large quarterly losses and declining sales.

But this also opens the door for looking at some stocks that have defied employee unrest. Dillard’s made the list all 4 years. In 2012 the stock rose from $54 to $66, yet appeared #2 on the list. In 2013 the stock rose to $85 as it made the list #3. 2014 the stock made it to $119, and was sixth. In 2015 the stock peaked at $149, but has recently declined to $111 as it made the list #2.

Similarly Express Scripts rose from $53 in 2012 to $62 in 2013 when it appeared on the list in position #2. In 2014 it rose to $71 as it remained #2. And it 2015 the stock is at $85 as it topped the list #1.

It would be worthwhile to look at the clues employees are sending. Express Scripts employees are loudly complaining (louder than literally any other company) across multiple years of being overworked, overstressed, underpaid and without any job security. As are Dillard’s employees, who are the most outspoken in retail. How long will profit improvements be sustainable in these companies?

While the data is less clear on Dollar General, it appeared on the list as #4 in 2013. Then Family Dollar appeared on the list as #9 in 2014. Dollar General subsequently tried buying Family Dollar, and reappeared on the list as #10 in 2015. What are employees saying about the sustainability of the “dollar store” segment in a very tough retail market with growing internet competitors?

Any CEO can slash employee costs and payroll for a few years, but at some point the model simply collapses – aka, Sears Holdings and Radio Shack. Or there is a loss of identity as suffered by Office Max, Jos. A Banks and Family Dollar. It would be worthwhile for anyone to listen carefully to the feedback of these employees before investing in company equity, investing one’s livelihood as an employee, investing one’s resources to be a supplier, or investing one’s tax base as a community official.

There are a number of “one off” issues on the list. Companies appear once primarily due to bad CEO performance (Xerox, #5 this year, HP #8 in 2012 as the revolving door on the CEO office reached a high pitch.) Or due to some change in market competition.

But it is possible to look through these issues – which could become future trends but show limited insight today – to see that an aggregated employee view of leadership offers insights not always found in the P&L or management’s discussion of earnings. If you choose to put your resources into these companies, be aware of the risks warnings being sent by employees!

Please refer to the 24x7WallStreet.com site for deeper information on how the list was compiled, who is on each list, and their editor’s opinions of employee comments. 24×7 list in 2015 – 24×7 list in 2014 – 24×7 list in 2013 – 24×7 list in 2012

by Adam Hartung | May 31, 2015 | Current Affairs, Defend & Extend, In the Whirlpool, Leadership, Web/Tech

Information technology (IT) services company Computer Sciences Corporation (CSC) recently announced it is splitting into two separate companies. One will “focus” on commercial markets, the other will “focus” on government contracts. Ostensibly, as we’ve heard before, leadership would like investors, employees and customers to believe this is the answer for a company that has incurred a number of high profile failed contracts, a turnover in leadership, vast losses and declining revenue.

Oh boy.

After years of poor performance, and an investigation by the UK parliament into a failed contract for the National Health Services, in 2012 CSC brought in a new CEO. Like most new CEOs, his first action was to announce a massive cost-cutting program. That primarily meant vast layoffs. So out the door went thousands of people in order to hopefully improve the P&L.

Only a services company doesn’t have any hard assets. The CSC business requires convincing companies, or government agencies, to let them take over their data centers, or PC deployment, or help desk, or IT development, or application implementation – in other words to outsource some part (or all) of the IT work that could be done internally. Winning this work has been an effort to demonstrate you can hire better people, that are more productive, at lower cost than the potential client.

So when CSC undertook a massive layoff, service levels declined. It was unavoidable. Where before CSC had 10 people doing something (or 1,000) now they have 7 (or 700). It’s not hard to imagine what happens next. Morale declines as layoffs ensue, and the overworked remaining employees feel (and perhaps really are) overworked. People leave for better jobs with higher pay and less stress. Yet, the contract requirements remain, so clients often start complaining about performance, leading to more pressure on the remaining employees. A vicious whirlpool of destruction starts, as things just keep getting worse.

Immediately after taking the CEO job in 2012 Mike Lawrie declared a massive $4.3B loss. This allowed him to “bring forward” anticipated costs of the anticipated layoffs, cancelled contracts, etc. Most importantly, it allowed him to “cost shift” future costs into his first year in the job – the year in which he would not be fired, regardless how much he wrote off. This is a classic financial machination applied by “turnaround CEOs” in order to blame the last guy for not being truthful about how badly things were, while guaranteeing the end of the new guy’s first year would show a profit due to the huge cost shift.

True to expectations, after one year with Lawrie as CEO, CSC declared a $1B profit for fyscal 2013 (about 20% of the previous write-off.) But then fyscal 2014 returned to the previous norm, as profits shrunk to just $674M on about $12B revenues (~5% net margin.) For 4th quarter of fyscal 2015 revenues dropped another 12.6% – not hard to imagine given the layoffs and ensuing customer dissatisfaction. Most troubling, the commercial part of CSC, which represents 75% of revenue, saw all parts of the business decline between 15-20%, while the federal contracting (much harder to cancel) remained flat. This is not the trajectory of a turnaround.

CEO Lawrie blames the deteriorating performance on execution missteps. And he has promised to keep his eyes carefully on the numbers. Although he has admitted that he doesn’t really know when, or if, CSC will return to any sort of growth.

No wonder that for more than a year prior to this split CSC was unable to sell itself. Despite a lot of hard effort, no banker was able to put together a deal for CSC to be purchased by a competitor or a private banking (hedge fund) operation.

If none of the professionals in making splits and turnarounds were willing to take on this deal, why should individual investors? In this case, watching people walk away should be a clear indicator of how bad things are, and how clueless leadership is regarding a fix for the problems.

The real problem at CSC isn’t “execution.” The real problem is that the market has shifted substantially. For decades CSC’s outsourcing business was the norm. But today companies don’t need a lot of what CSC outsources. They are closing down those costly operations and replacing them with cloud services, cloud application development and implementation, mobile deployments and significant big data analytics. Or looking for new services to solve problems like cybersecurity threats. CSC quite simply hasn’t done anything in those markets, and it is far, far behind. It is a big dinosaur rapidly being overtaken by competitors moving more quickly to new solutions.

One of CSC’s biggest competitors is IBM, which itself has had a series of woes. However, IBM has very publicly set up a partnership with Apple and is moving rapidly to develop industry-specific software as a service (SaaS) offerings that are mobile and operate in the cloud. These targeted enterprise solutions in health care, finance and other industries are designed to make the services offered by CSC obsolete.

Although it may have had a huge client base of 1,000 customers. And CSC brags that 175 of the Fortune 500 buy some services from it, exactly what does CSC bring to the table to keep these customers? Years of cost cutting means the company has not invested in the kinds of solutions being offered by IBM and competitors such as Accenture, HP and Dell domestically – and WiPro, TCS (Tata Consulting Services,) Infosys and Cognizant offshore. Not to mention dozens of up-and-coming small competiters who are right on the market for targeted solutions with the latest technology such as 6D Gobal Technologies. CSC is still stuck in its 1980s consulting model, and skill set, in a world that is vastly different today.

CSC has no idea how to “focus” on clients. That would mean investing in modern solutions to rapidly changing client needs. CSC failed to do that 15 years ago when most outsourcing involved heavy use of offshore resources. And CSC has never caught up. Leadership overly relied on selling old services, and discounting. It’s model caused it to underbid projects, until the UK government almost shut the company down for its inability to deliver, and constantly hiding actual results.

CSC has no idea how to “focus” on clients. That would mean investing in modern solutions to rapidly changing client needs. CSC failed to do that 15 years ago when most outsourcing involved heavy use of offshore resources. And CSC has never caught up. Leadership overly relied on selling old services, and discounting. It’s model caused it to underbid projects, until the UK government almost shut the company down for its inability to deliver, and constantly hiding actual results.

Now CSC lacks any of the capabilities, people or skills to offer clients what they want. Its diffuse customer base is more a liability than a benefit, because these customers are “end of life” for the services CSC offers. Years of declining revenues demonstrate that as value declines, contracts are either allowed to go to very cheap offshore providers, lapse completely or cancelled early in order to shift client resources to more important projects where CSC cannot compete.

This split is just an admission that leadership has no idea what to do next. Customers are leaving, and revenues are declining. Margins, at 5%, are terrible and there is no money to invest in anything new. Some of the world’s best investors have looked at CSC deeply and chosen to walk away. For employees and individual investors it is time to admit that CSC has a limited future, and it is time to find far greener pastures.

by Adam Hartung | May 22, 2015 | In the Whirlpool, Leadership, Lock-in, Web/Tech

Hewlett Packard yesterday announced second quarter results. And they were undoubtedly terrible. Revenue compared to a year ago is down 7%, net income is down 21% as the growth stall at HP continues.

Yet, CEO Meg Whitman remains upbeat. She is pleased with “the continued success of our turnaround.” Which is good, because nobody else is. Rather than making new products and offering new solutions, HP has become a company that does little more than constantly restructure!

This latest effort, led by CEO Whitman, has been a split of the company into two corporations. For “strategic” (red flag) reasons, HP is dividing into a software company and a hardware company so that each can “focus” (second red flag) on its “core market” (third red flag.) But there seems to be absolutely no benefit to this other than creating confusion.

This latest restructuring is incredibly expensive. $1.8billion in restructuring charges, $1billion in incremental taxes, $400million annually in duplicated overhead services, then another $3billion in separation charges across the two new companies. That’s over $5B – which is more than HP’s net income in 2014 and 2013. There is no way this is a win for investors.

Additionally, HP has eliminated 48,000 jobs this this latest restructuring began in 2012. And the total will reach 55,000. So this is clearly not a win for employees.

The old HP will now be a hardware company, focused on PCs and printers. Both of which are declining markets as the world goes mobile. This is like the newspaper part of a media company during a split. An old business in serious decline with no clear path to sustainable sales and profits – much less growth. And in HP’s case it will be in a dog-eat-dog competitive battle to try and keep customers against Dell, Acer and Lenovo. Prices will keep dropping, and profits eroding as the world goes mobile. But despite spending $1.2billion to buy Palm (written off,) without any R&D, hard to see how this company returns profits to shareholders, generates new jobs, or launches new products for distributors and customers.

The new HP will be a software company. But it comes to market with almost no share against monster market leader Amazon, and competitors Microsoft and Cisco who are fighting to remain relevant. Even though HP spent $10B to buy ERP company Autonomy (written off) everyone has newer products, more innovation, more customers and more resources than HP.

Together there was faint hope for HP. The company could offer complete solutions. It could work with its distributors and value added resellers to develop unique vertical market solutions. By tweaking the various parts, hardware and software, HP had the possibility of building solutions that could justify premium prices and possibly create growth. But separated, these are now 2 “focused” companies that lack any new innovations, sell commodity products and lack enough share to matter in markets where share leads to winning developers and enterprise customers.

This may be the last stop for investors, and employees, to escape HP before things get a lot worse.

This may be the last stop for investors, and employees, to escape HP before things get a lot worse.

HP was the company that founded silicon valley. It was the tech place to work in the 1960s, 1970s and early 1980s. It was the Google, Facebook or Apple of that earlier time. When Carly Fiorina took over the dynamic and highly new product driven company in July, 1999 it was worth $45/share. She bought Compaq and flung HP into the commodity PC business, cutting new products and R&D. By the time the Board threw her out in 2005 the company was worth $35/share.

Mark Hurd took the CEO job, and he slashed and burned everything in sight. R&D was almost eliminated, as was new product development. If it could be outsourced, it was. And he whacked thousands of jobs. By killing any hope of growing the company, he improved the bottom line and got the stock back to $45.

Which is where it was 5 years ago today. But now HP is worth $35/share, once again. For investors, it’s been 25 years of up, down and sideways. The last 5 years the DJIA went up 80%; HP down 24%.

Companies cannot add value unless they develop new products, new solutions, new markets and grow. Restructuring after restructuring adds no value – as HP has demonstrated. For long-term investors, this is a painful lesson to learn. Let’s hope folks are getting the message loud and clear now.

by Adam Hartung | May 8, 2015 | Current Affairs, Defend & Extend, Food and Drink, In the Swamp, In the Whirlpool, Leadership

McDonald’s just had another lousy quarter. All segments saw declining traffic, revenues fell 11%. Profits were off 33%. Pretty well expected, given its established growth stall.

A new CEO is in place, and he announced is turnaround plan to fix what ails the burger giant. Unfortunately, his plan has been panned by just about everyone. Unfortunately, its a “me too” plan that we’ve seen far too often – and know doesn’t work:

- Reorganize to cut costs. By reshuffling the line-up, and throwing out a bunch of bodies management formerly said were essential, but now don’t care about, they hope to save $300M/year (out of a $4.5B annual budget.)

- Sell off 3,500 stores McDonald’s owns and operate (about 10% of the total.) This will further help cut costs as the operating budgets shift to franchisees, and McDonald’s book unit sales creating short-term, one-time revenues into 2018.

- Keep mucking around with the menu. Cut some items, add some items, try a bunch of different stuff. Hope they find something that sells better.

- Try some service ideas in which nobody really shows any faith, like adding delivery and/or 24 hour breakfast in some markets and some stores.

Needless to say, none of this sounds like it will do much to address quarter after quarter of sales (and profit) declines in an enormously large company. We know people are still eating in restaurants, because competitors like 5 Guys, Meatheads, Burger King and Shake Shack are doing really, really well. But they are winning primarily because McDonald’s is losing. Even though CEO Easterbrook said “our business model is enduring,” there is ample reason to think McDonald’s slide will continue.

Needless to say, none of this sounds like it will do much to address quarter after quarter of sales (and profit) declines in an enormously large company. We know people are still eating in restaurants, because competitors like 5 Guys, Meatheads, Burger King and Shake Shack are doing really, really well. But they are winning primarily because McDonald’s is losing. Even though CEO Easterbrook said “our business model is enduring,” there is ample reason to think McDonald’s slide will continue.

Possibly a slide into oblivion. Think it can’t happen? Then what happened to Howard Johnson’s? Bob’s Big Boy? Woolworth’s? Montgomery Wards? Size, and history, are absolutely no guarantee of a company remaining viable.

In fact, the odds are wildly against McDonald’s this time. Because this isn’t their first growth stall. And the way they saved the company last time was a “fire sale” of very valuable growth assets to raise cash that was all spent to spiffy up the company for one last hurrah – which is now over. And there isn’t really anything left for McDonald’s to build upon.

Go back to 2000 and McDonald’s had a lot of options. They bought Chipotle’s Mexican Grill in 1998, Donato’s Pizza in 1999 and Boston Market in 2000. These were all growing franchises. Growing a LOT faster, and more profitably, than McDonald’s stores. They were on modern trends for what people wanted to eat, and how they wanted to be served. These new concepts offered McDonald’s fantastic growth vehicles for all that cash the burger chain was throwing off, even as its outdated yellow stores full of playgrounds with seats bolted to the floors and products for 99cents were becoming increasingly not only outdated but irrelevant.

But in a change of leadership McDonald’s decided to sell off all these concepts. Donato’s in 2003, Chipotle went public in 2006 and Boston Market was sold to a private equity firm in 2007. All of that money was used to fund investments in McDonald’s store upgrades, additional supply chain restructuring and advertising. The “strategy” at that time was to return to “strategic focus.” Something that lots of analysts, investors and old-line franchisees love.

But look what McDonald’s leaders gave up via this decision to re-focus. McDonald’s received $1.5B for Chipotle. Today Chipotle is worth $20B and is one of the most exciting fast food chains in the marketplace (based on store growth, revenue growth and profitability – as well as customer satisfaction scores.) The value of all of the growth gains that occurred in these 3 chains has gone to other people. Not the investors, employees, suppliers or franchisees of McDonald’s.

We have to recognize that in the mid-2000s McDonald’s had the option of doing 180degrees opposite what it did. It could have put its resources into the newer, more exciting concepts and continued to fidget with McDonald’s to defend and extend its life even as trends went the other direction. This would have allowed investors to reap the gains of new store growth, and McDonald’s franchisees would have had the option to slowly convert McDonald’s stores into Donato’s, Chipotle’s or Boston Market. Employees would have been able to work on growing the new brands, creating more revenue, more jobs, more promotions and higher pay. And suppliers would have been able to continue growing their McDonald’s corporate business via new chains. Customers would have the benefit of both McDonald’s and a well run transition to new concepts in their markets. This would have been a win/win/win/win/win solution for everyone.

But it was the lure of “focus” and “core” markets that led McDonald’s leadership to make what will likely be seen historically as the decision which sent it on the track of self-destruction. When leaders focus on their core markets, and pull out all the stops to try defending and extending a business in a growth stall, they take their eyes off market trends. Rather than accepting what people want, and changing in all ways to meet customer needs, leaders keep fiddling with this and that, and hoping that cost cutting and a raft of operational activities will save the business as they keep focusing ever more intently on that old core business. But, problems keep mounting because customers, quite simply, are going elsewhere. To competitors who are implementing on trends.

The current CEO likes to describe himself as an “internal activist” who will challenge the status quo. But he then proves this is untrue when he describes the future of McDonald’s as a “modern, progressive burger company.” Sorry dude, that ship sailed years ago when competitors built the market for higher-end burgers, served fast in trendier locations. Just like McDonald’s 5-years too late effort to catch Starbucks with McCafe which was too little and poorly done – you can’t catch those better quality burger guys now. They are well on their way, and you’re still in port asking for directions.

McDonald’s is big, but when a big ship starts taking on water it’s no less likely to sink than a small ship (i.e. Titanic.) And when a big ship is badly steered by its captain it flounders, and sinks (i.e. Costa Concordia.) Those who would like to think that McDonald’s size is a benefit should recognize that it is this very size which now keeps McDonald’s from doing anything effective to really change the company. Its efforts (detailed above) are hemmed in by all those stores, franchisees, commitment to old processes, ingrained products hard to change due to installed equipment base, and billions spent on brand advertising that has remained a constant even as McDonald’s lost relevancy. It is now sooooooooo hard to make even small changes that the idea of doing more radical things that analysts are requesting simply becomes impossible for existing management.

And these leaders, frankly, aren’t even going to try. They are deeply wedded, committed, to trying to succeed by making McDonald’s more McDonald’s. They are of the company and its history. Not the CEO, or anyone on his team, reached their position by introducing a revolutionary new product, much less a new concept – or for that matter anything new. They are people who “execute” and work to slowly improve what already exists. That’s why they are giving even more decision-making control to franchisees via selling company stores in order to raise cash and cut costs – rather than using those stores to introduce radical change.

These are not “outside thinkers” that will consider the kinds of radical changes Louis V. Gerstner, a total outsider, implemented at IBM – changing the company from a failing mainframe supplier into an IT services and software company. Yet that is the only thing that will turn around McDonald’s. The Board blew it once before when it sold Chipotle, et.al. and put in place a core-focused CEO. Now McDonald’s has fewer resources, a lot fewer options, and the gap between what it offers and what the marketplace wants is a lot larger.

by Adam Hartung | Mar 9, 2015 | Current Affairs, Defend & Extend, In the Whirlpool, Leadership

Best Buy, the venerable electronics retailer, is hitting 52 week highs. Coming off a low of $24 in April, 2014 the current price of about $40 is a 67% increase in just 10 months. Analysts are now cheering investors to own the stock, with Marketwatch pronouncing that the last bearish analyst has thrown in the towel.

If you are a trader, perhaps you want to consider this stock. But if you aren’t an investment professional, and you buy and hold stocks for years, then Best Buy is not a stock you should own.

The bullish case for owning Best Buy is based on recovering sales per store, and recovering earnings, after a reduction in the number of stores, and employees, lowered costs. Further, with Radio Shack now in bankruptcy sales are showing an uptick as customers swing over. And that is expected to continue as Sears closes more stores on its marches toward bankruptcy. Additionally, it is hoped that lower gasoline prices will allow consumers to spend more on electronics and appliances at Best Buy.

But, this completely ignores the trend toward on-line retail sales, and the long-term deleterious impact this trend will have on Best Buy. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, on-line sales as a percent of all retail have grown from less than 2.4% in 2005 to over 7.6% by end of 2014 – more than tripling! But more critical to this discussion, all retail sales includes automobiles, lumber, groceries – lots of things where there is little or no online volume.

As most folks know, the number one category for online sales is computers and consumer electronics, which consistently accounts for about 20% of ALL online retail. In fact, about 25% of all consumer electronics are sold online. So the growth in online retail is disproportionately in the Best Buy wheelhouse. The segment where Best Buy competes against streamlined online retailers such as NewEgg.com, ThinkGeek.com and the ever-dominant Amazon.com.

So while in the short term some traditional retail customers will now shift demand to Best Buy, this is not unlike the revenue “bounce” Best Buy received when Circuit City failed. Short term up, but the long term trend continued hammering away at Best Buy’s core market.

This is a big deal because the marginal economic impact of this shift is horrific to Best Buy. In traditional retail most costs are “fixed,” meaning they can’t be changed much month to month. The cost of real estate, store maintenance, utilities and staff cannot be easily adjusted – unless there is a decision to close a gob of stores. Thus losing even a few sales, what economists call “marginal” sales, wreaks havoc on earnings.

Back in 2010 and 2011 Best Buy made a net income (’12 and ’13 were losses) of about 2.6% – or about $2.60 on every $100 revenue. Cost of Goods sold is about 75% of revenue. So on $100 of revenue, $25 is available to cover fixed costs. If revenue falls by just $10, Best Buy loses $2.50 of margin to cover fixed costs. Remember, however, that the net income is only $2.60. So losing 10% of revenue ($10 out of the $100) means Best Buy loses $2.50 of contribution to fixed costs, and that is deducted from net income of $2.60, leaving Best Buy with a meager 10cents of profitability. A 10% loss of revenue wipes out 96% of profits!

Now you know why retailers who lose even a small part of their sales are suddenly closing stores right and left.

Looking forward, online retail sales are forecast to grow by another 57%, reaching 11% of total retail by 2018. But, as we know, this is disproportionately going to be driven by consumer electronics. Which means that while sales for Best Buy stores are up short term, long term they will plummet. That means there will be more store closings, and layoffs as sales shrink. And, increasingly Best Buy will have to compete head-to-head online against entrenched, leading competitors who have been stealing market share for 10+ years.

If you want to trade on the short-term uptick in revenue, and return to slight profitability, then hold your breath and see if you can outsmart the market by picking the right time, and price, for buying and selling Best Buy. But, if you like to invest in strong companies you expect to grow for another 5 years without having to be a market timer, then avoid Best Buy.

Quite simply, it is never a good idea to bet against a long term trend. Short term aberrations will happen, and it may look like the trend has changed. But the trend to online commerce is picking up steam, not reducing. If you want to invest in retail, you want to invest in those companies that demonstrate they can capture the customer’s revenue in the growing, online marketplace.

by Adam Hartung | Jan 29, 2015 | Current Affairs, In the Whirlpool, Leadership, Web/Tech

This week Yahoo announced it is spinning off the last of its Alibaba holdings. This is a big deal, because it might well signal the end of Yahoo.

Yahoo created internet advertising. Yahoo was once the #1 home page for browsers across America. But the company has floundered for years, riddled with CEO problems, a contentious Board of Directors and no strategy for dealing with Google which overtook it in all markets.

To much fanfare the Board hired Marissa Mayer, a Google wunderkind we were told, in July, 2012 to mount a serious turnaround. And during her leadership the company’s stock value has tripled – from about $14.50/share to about $43.50. You would think investors would be thrilled and the company would be on the right track.

Only almost all that value creation was due to a stock investment made in 2005 – when Jerry Yang invested $1B to buy 40% of Alibaba. And Alibaba in 2014 became the most valuable IPO in history.

Yahoo today is valued at about $46B. The Alibaba shares being spun out are valued at between $40B and $44B. Which means that after adjusting for the ownership in Yahoo Japan (valued at $2.3B) the core Yahoo ad and portal business is worth between $2B and $4.7B. With just over $1B shares outstanding, that puts a value on Yahoo’s core business of between $2.00-$4.70/share – or about 1/6 to 1/3 the value when Ms. Mayer became CEO.

A highest value of $4.7B for the operating business of Yahoo puts it on par with Groupon. And worth far less than competitors Google ($347B) and Facebook ($212B). Even upstart, and often maligned, social media companies Twitter ($24B) and LinkedIn ($27B) have valuations 5 times Yahoo.

Unfortunately, this latest leader and her team haven’t been any more effective at improving the company’s business than previous regimes. Under CEO Mayer Yahoo used gains from Alibaba’s valuation to invest about $2.1B in 49 outside companies – with $2B of that being acquisitions of technology companies Flurry ($200M), BrightRoll ($640M) and Tumblr ($1.1). Under the most optimistic view of Yahoo, leadership spent 40% of the company’s value in acquisitions that have made no difference to ad revenues or profits.

In fact, Yahoo’s business revenues, and profits, have declined for 6 consecutive quarters. Despite the CEO’s mandate that employees could no longer work from home. A kerfuffle that proved yet another management distraction, and apparently an effort to cut staff without it looking like a layoff.

Meanwhile there have been big efforts to boost people going to the Yahoo portal. Such as hiring broadcaster Katie Couric to beef up the news section, and former New York Times tech columnist David Pogue to deepen tech coverage and New York Times Magazine political writer Matt Bai to draw in more readers. But these have done nothing to move the needle.

Consistently declining display advertising has left search ads a bigger, and more profitable, business. And while Yahoo’s CEO has been teasing ad agencies that she might begin another big brand campaign, including TV, to bring Yahoo more attention – and hopefully more advertisers – there is no evidence anyone cares as more and more dollars flow to “programmatic” ad buying where Google is king. In the digital ad marketplace Google has 31% share, Facebook 7.75% share and Yahoo a meager 2.36% share.

Soon there will be little left of the once mighty Yahoo. It has pretty much lost relevancy. Large investors are crying for a merger with AOL, whose inability to grow its portal, ad and media businesses has left its market cap at a mere $3.7B. But combining two companies that are market irrelevant, and declining, will probably have the same outcome as happened when merging KMart and Sears. The Yahoo growth stall remains intact, and revenues will decline along with profits as the market continues shifting to powerful and growing competitors Google, Facebook and other social media companies. Only now Yahoo’s leaders won’t have the Alibaba value mountain to hide behind

by Adam Hartung | Dec 11, 2014 | Current Affairs, Defend & Extend, In the Whirlpool, Leadership, Lifecycle, Television, Web/Tech

The trend toward the death of broadcast TV as we’ve known it keeps moving forward. This trend may not happen as fast as the death of desktop computers, but it is a lot faster than glacier melting.

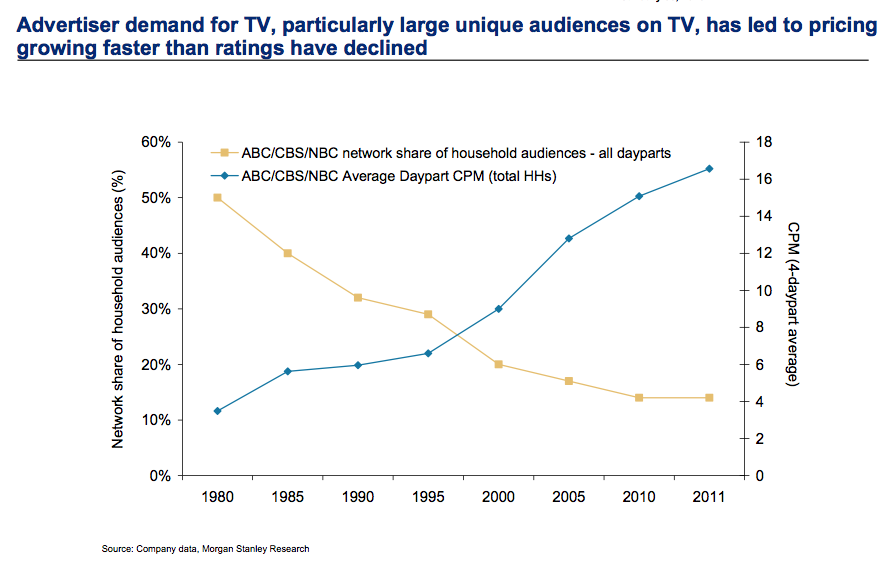

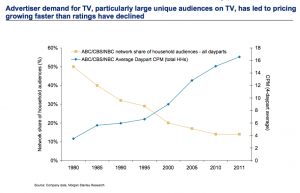

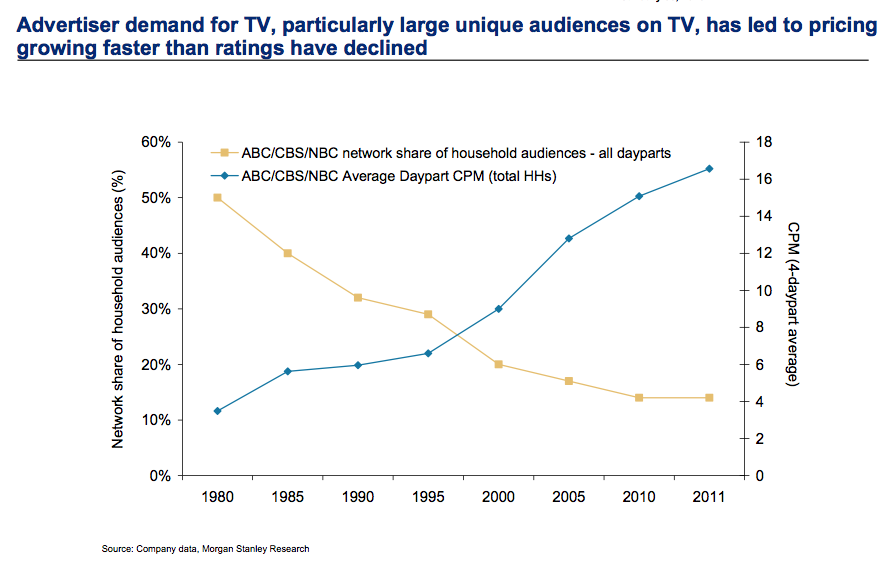

This television season (through October) Magna Global has reported that even the oldest viewers (the TV Generation 55-64) watched 3% less TV. Those 35-54 watched 5% less. Gen Xers (25-34) watched 8% less, and Millenials (18-24) watched a whopping 14% less TV. Live sports viewing is not even able to maintain its TV audience, with NFL viewership across all networks down 10-19%.

Everyone knows what is happening. People are turning to downloaded entertainment, mostly on their mobile devices. With a trend this obvious, you’d think everyone in the media/TV and consumer goods industries would be rethinking strategy and retooling for a new future.

But, you would be wrong. Because despite the obviousness of the trend, emotional ties to hoping the old business sticks around are stronger than logic when it comes to forecasting.

CBS predicted at the beginning of 2014 TV ad revenue would grow 4%. Oops. Now CBS’s lead forecaster is admitting he was way off, and adjusted revenues were down 1% for the year. But, despite the trend in viewer behavior and ad expenditures in 2014, he now predicts a growth of 2% for 2015.

That, my young friends, is how “hockey stick” forecasts are created. A lot of old assumptions, combined with a willingness to hope trends will be delayed, and you can ignore real data while promising people that the future will indeed look like the past – even when it defies common sense.

To compensate for fewer ads the networks have raised prices on all ads. But how long can that continue? This requires a really committed buyer (read more about CMO weaknesses below) who simply refuses to acknowledge the market has shifted and the dollars need to shift with it. That cannot last forever.

Meanwhile, us old folks can remember the days when Nielsen ratings determined what was programmed on TV, as well as what advertisers paid. Nielsen had a lock on measuring TV audience viewing, and wielded tremendous power in the media and CPG world.

But now AC Nielsen is struggling to remain relevant. With TV viewership down, time shifting of shows common and streaming growing like the proverbial weed Nielsen has no idea what entertainment the public watches. They don’t know what, nor when, nor where. Unwilling to move quickly to develop tools for catching all the second screen viewing, Nielsen has no plan for telling advertisers what the market really looks like – and the company looks to become a victim of changing markets.

Which then takes us to looking at those folks who actually buy ads that drive media companies. The Chief Marketing Officers (CMOs) of CPG companies. Surely these titans of industry are on top of these trends, and rapidly shifting their spending to catch the viewers with the most ads placed for the lowest cost.

You would wish.

Unfortunately, because these senior executives are in the oldest age groups, they are a victim of their own behavior. They still watch TV, so assume others must as well. If there is cyber-data saying they are wrong, well they simply discount that data. The Nielsen’s aren’t accurate, but these execs still watch the ratings “because it’s the best info we have” – a blatant untruth by the way. But Nielsen does conveniently reinforce their built in assumptions, and their hope that they won’t have to change their media spend plans any time soon.

Further, very few of these CMOs actually use social media. The vast majority watch their children, grandchildren and young employees use mobile devices constantly – and they bemoan all the activity on YouTube, Facebook, Instagram and Twitter – or for the most part even Linked-in. But they don’t actually USE these products. They don’t post information. They don’t set up and follow channels. They don’t connect with people, share information, exchange photos or tell stories on social media. Truthfully, they ignore these trends in their own lives. Which leaves them woefully inept at figuring out how to change their company marketing so it can be more relevant.

The trend is obvious. The answer, equally so. Any modern marketer should be an avid user of social media. Most network heads and media leaders are farther removed from social media than the Pope! They don’t constantly download entertainment, and exchanging with others on all the platforms. They can’t manage the use of these channels when they don’t have a clue how they work, or how other people use them, or understand why they are actually really valuable tools.

Are you using these modern tools? Are you actually living, breathing, participating in the trends? Or are you, like these outdated execs, biding your time wasting money on old programs while you look forward to retirement? And likely killing your company.

When trends emerge it is imperative we become part of that trend. You can’t simply observe it, because your biases will lead you to hope the trend reverts as you continue doing more of the same. A leader has to adopt the trend as a leader, be a practicing participant, and learn how that trend will make a substantial difference in the business. And then apply some vision to remain relevant and successful.