by Adam Hartung | Dec 24, 2014 | Defend & Extend, Disruptions

The Twelve Days of Christmas refers to an ancient festive season which begins on December 25. Colonial Americans modified this a bit by creating wreaths which they hung on neighbors’ doors on December 24 in anticipation of starting the festival of twelve days, which historically included feasts and celebrations.

Better known is the song “The Twelve Days of Christmas” which is believed to have started as a French folk rhyme, then later published in 1780 England. The song commemorates the twelve days of Christmas by offering ever grander gifts on each day of the holiday season.

So, it being Christmas Eve I am stealing this idea completely and offering my list of the 12 gifts investors would like to receive this holiday season from the companies into which they invest:

- Stop waxing eloquently about what you did last year or quarter. Yesterday has come and gone. Tell me about the future.

- Tell me about important trends that are going to impact your business. Is it demographics, aging population, the ecology movement, digitization, regulatory change, organic foods, mobility, mobile payments, nanotech, biotech… ? What are the critical trends that will impact your business going forward?

- Tell me your future scenarios. How will these trends change the way your customers and your company will behave? What are your most likely scenarios (and don’t try to be creative in an effort to preserve the status quo!)

- Tell me how the game will change for your industry over the next 1, 3, and 5 years. How will things be different for the industry, based on the trends and scenarios. The world is a fast changing place, and I want to know how this will change your industry.

- Tell me about the customers you lost last year. I gain no value from hearing about, or from, your favorite customers that love what currently do. Instead, bring me info on the customers who are buying alternative products, changing their behaviors, in ways that might impact sales. Even if these changes are only a small percentage of revenue.

- Tell me who the competitors are that are trying to change the game. Don’t tell me that these companies will fail. Tell me who the folks are that are really trying to do something new and different.

- Tell me about the fringe competitors. The ones you constantly say do not matter because they are small, or not part of the historical industry, or from some distant location where you don’t now compete. Tell me about the companies doing the new things which are seen as remote and immaterial, but are nibbling at the edges of the market.

- Tell me how you are reacting to potential game changers in your market. What are your plans to deal with disruptive competitors and disruptive innovations affecting your way of doing business? Other than working harder, faster, cheaper and planning to do better, what are you planning to do differently?

- Tell me how you intend to be a market game changer. Tell me what you intend to do that aligns with trends and leads the company toward fulfilling future scenarios as a market leader.

- Tell me what projects you are undertaking to experiment with new forms of competition, attracting new customers and creating new markets. Tell me about your teams that are working in white space to discover new opportunities.

- Tell me how you will disrupt your own organization so the constant effort to enhance the old success formula doesn’t kill any effort to do something new and different. How will you keep these experimental white space teams from being killed, or simply starved of resources, by the organizational inertia to defend and extend the status quo.

- Tell me the goals of these project teams, and how they will be nurtured and supplemented, as well as evaluated, to lead the company in new directions. Don’t just tell me that you will measure sales or profits, but rather real goals that measure market learning and ability to understand new customer behaviors.

If investors had this transparency, rather than merely reams and reams of historical data, just imagine how much smarter we could all invest.

Happy Holidays!

by Adam Hartung | Dec 18, 2014 | Current Affairs, Defend & Extend, Food and Drink, Leadership, Lifecycle

It is that time of year when many of us celebrate with an alcoholic beverage. But increasingly in America, that beverage is not beer. Since 2008, American beer sales have fallen about 4%.

But that decline has not been equally applied to all brands. The biggest, old line brands have suffered terribly. Nearly gone are old brands like Milwaukee’s Best, which were best known for being low priced – and certainly not focused on taste. But the most hurt, based on volume declines, have been what were once the largest brands; Budweiser, Miller Lite and Miller High Life. These have lost more than a quarter of their volume, losing a whopping 13million barrels/year of demand. These 3 brand declines account for 6% reduction in the entire beer market.

The popular myth is that this has been due to the rise of craft beers. And there is no doubt, craft beer sales have done well. Sales are up 80%. Many articles (including the WSJ)tout the growth of craft beers, which are ostensibly more tasty and appealing, as being the reason old-line brands have declined. It is an easy explanation to accept, and has largely gone unchallenged. Even the brewer of Budweiser, Annheuser-Busch InBev, has reacted to this argument by taking the incredible action of dropping clydesdale horses from their ads after 81 years – in an effort to woo craft beer drinkers, which are thought to be younger and less sentimental about large horses.

This all makes sense. Too bad it’s the wrong conclusion – and the wrong actions being taken.

Realize that craft beer sales are up from a small base, and today ALL craft beer sales still account for only 7.6% of the market. In fact, ALL craft beers combined sell only the same volume as the now smaller Budweiser. The problem with Budweiser sales – and sales of other big name brand beers – is a change in demographics.

Drinkers of Budweiser and Lite are simply older. These brands rose to tremendous dominance in the 1970s. Many of those who loved this brand are simply older – or dead. Where a hard working fellow in his 30s or 40s might enjoy a six pack after work, today that Boomer (if still alive) is somewhere between late 50s and 70s. Now, a single beer, or maybe two, will suffice thank you very much. And, equally challenging for sales, today’s Boomer is more often drinking a hard liquor cocktail, and a glass of wine with dinner. Beer drinking has its place, but less often and in lower quantities.

Meanwhile, Hispanics are a growing demographic. Hispanics are the largest non-white population in America, at 54million, and represent over 17% of all Americans. With a growth rate of 2.1%, Hispanics are also one of the fastest growing demographic segments – and increasingly important given their already large size. Hispanics are truly becoming a powerful buying group in American economics.

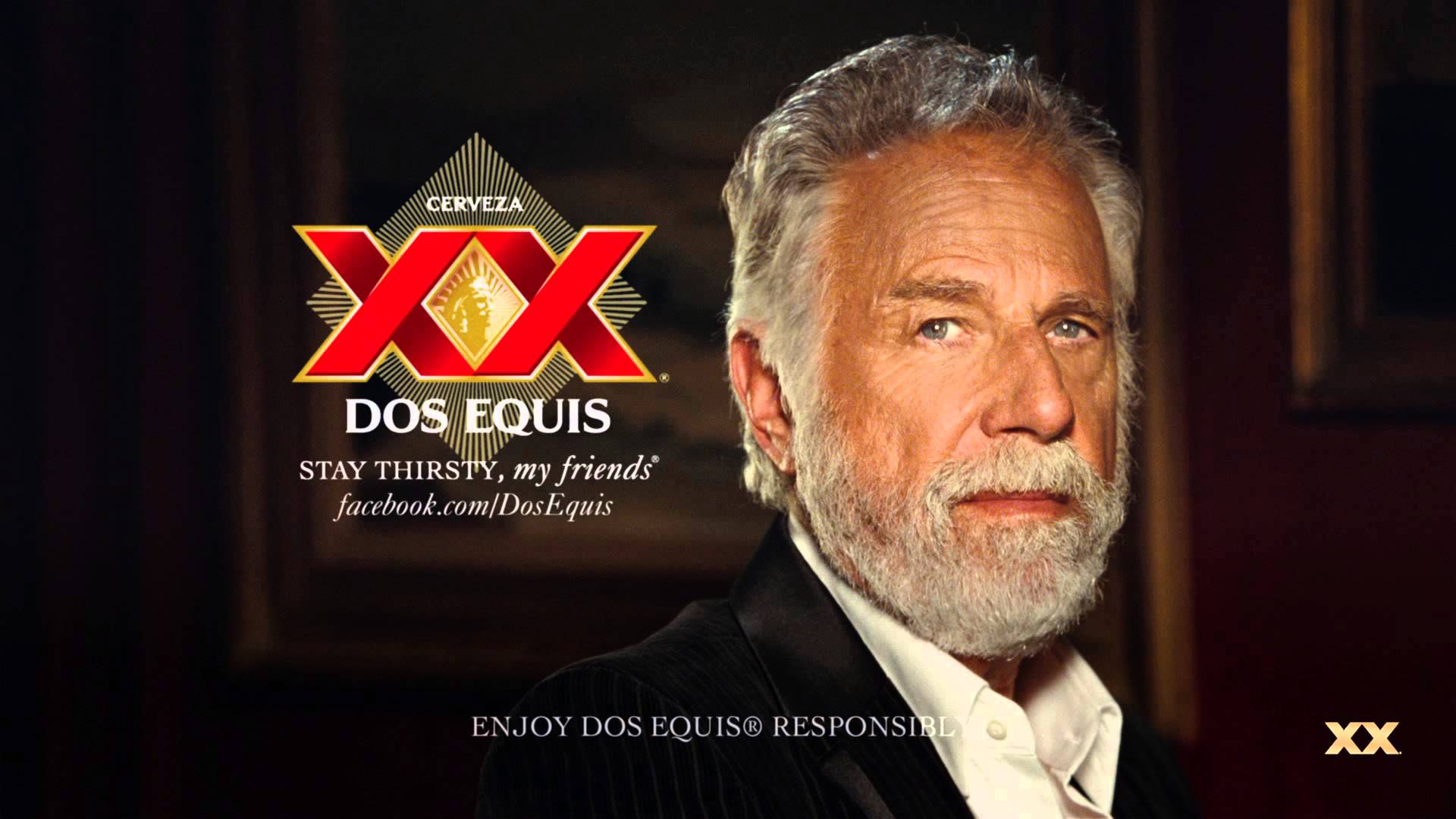

So, just as decline in Boomer population and consumption has hurt the once great beer brands, we can look at the growth in Hispanic demographics and see a link to sales of growing brands. Two significant (non-craft volume) beer brands that more than doubled sales since 2008 are Modelo Especial and Dos Equis. In fact, these were the 2 fastest growing brands in America, even though the first does no English language advertising at all, and the latter only lightly funds advertising with an iconic multi-year campaign. Together their sales total almost 5.4M barrels – which makes these 2 brands equal to 1/3 the ENTIRE craft beer marketplace. And growing 33% faster!

Chasing the myth of craft sales is doing nothing for InBev and MillerCoors as they try to defend and extend outdated brands. On the other hand, Heineken controls Dos Equis, and Constellation Brands controls Modello Especial. These two companies are squarely aligned with demographic trends, and well positioned for growth.

So, be careful the next time you hear some simple explanation for why a product or service is declining. The answer might sound appealing, but have little economic basis. Instead, it is much smarter to look at big trends and you’ll likely see why in the same market one product is growing, while another is declining. Trends – such as demographics – often explain a lot about what is happening, and lead you to invest much smarter.

by Adam Hartung | Dec 11, 2014 | Current Affairs, Defend & Extend, In the Whirlpool, Leadership, Lifecycle, Television, Web/Tech

The trend toward the death of broadcast TV as we’ve known it keeps moving forward. This trend may not happen as fast as the death of desktop computers, but it is a lot faster than glacier melting.

This television season (through October) Magna Global has reported that even the oldest viewers (the TV Generation 55-64) watched 3% less TV. Those 35-54 watched 5% less. Gen Xers (25-34) watched 8% less, and Millenials (18-24) watched a whopping 14% less TV. Live sports viewing is not even able to maintain its TV audience, with NFL viewership across all networks down 10-19%.

Everyone knows what is happening. People are turning to downloaded entertainment, mostly on their mobile devices. With a trend this obvious, you’d think everyone in the media/TV and consumer goods industries would be rethinking strategy and retooling for a new future.

But, you would be wrong. Because despite the obviousness of the trend, emotional ties to hoping the old business sticks around are stronger than logic when it comes to forecasting.

CBS predicted at the beginning of 2014 TV ad revenue would grow 4%. Oops. Now CBS’s lead forecaster is admitting he was way off, and adjusted revenues were down 1% for the year. But, despite the trend in viewer behavior and ad expenditures in 2014, he now predicts a growth of 2% for 2015.

That, my young friends, is how “hockey stick” forecasts are created. A lot of old assumptions, combined with a willingness to hope trends will be delayed, and you can ignore real data while promising people that the future will indeed look like the past – even when it defies common sense.

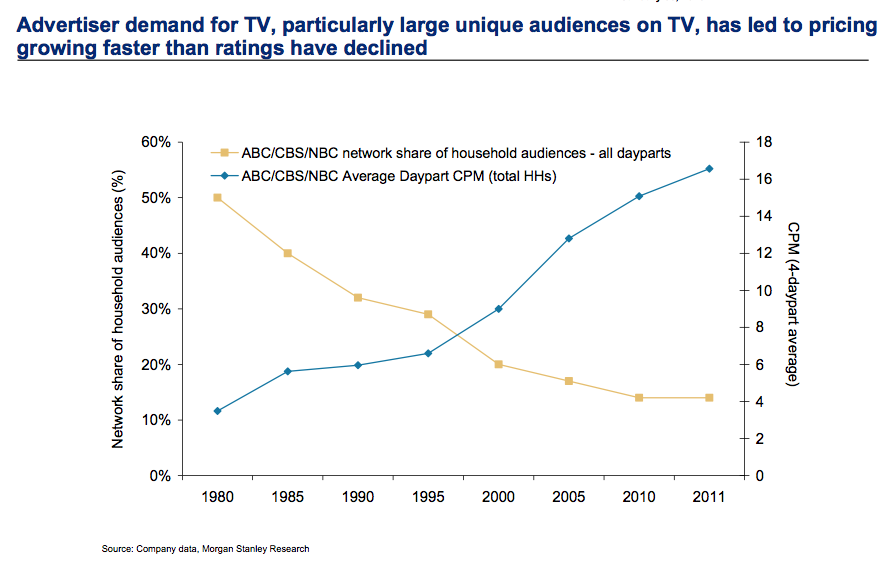

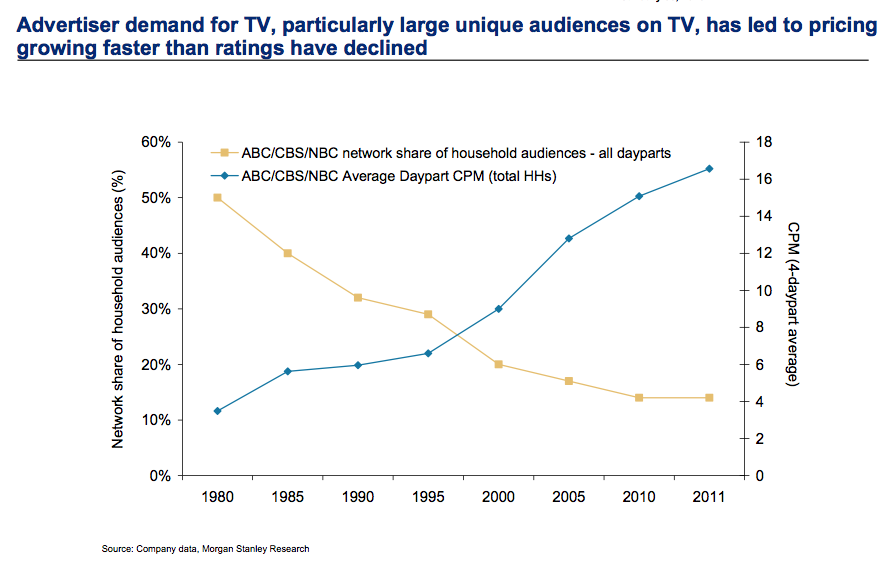

To compensate for fewer ads the networks have raised prices on all ads. But how long can that continue? This requires a really committed buyer (read more about CMO weaknesses below) who simply refuses to acknowledge the market has shifted and the dollars need to shift with it. That cannot last forever.

Meanwhile, us old folks can remember the days when Nielsen ratings determined what was programmed on TV, as well as what advertisers paid. Nielsen had a lock on measuring TV audience viewing, and wielded tremendous power in the media and CPG world.

But now AC Nielsen is struggling to remain relevant. With TV viewership down, time shifting of shows common and streaming growing like the proverbial weed Nielsen has no idea what entertainment the public watches. They don’t know what, nor when, nor where. Unwilling to move quickly to develop tools for catching all the second screen viewing, Nielsen has no plan for telling advertisers what the market really looks like – and the company looks to become a victim of changing markets.

Which then takes us to looking at those folks who actually buy ads that drive media companies. The Chief Marketing Officers (CMOs) of CPG companies. Surely these titans of industry are on top of these trends, and rapidly shifting their spending to catch the viewers with the most ads placed for the lowest cost.

You would wish.

Unfortunately, because these senior executives are in the oldest age groups, they are a victim of their own behavior. They still watch TV, so assume others must as well. If there is cyber-data saying they are wrong, well they simply discount that data. The Nielsen’s aren’t accurate, but these execs still watch the ratings “because it’s the best info we have” – a blatant untruth by the way. But Nielsen does conveniently reinforce their built in assumptions, and their hope that they won’t have to change their media spend plans any time soon.

Further, very few of these CMOs actually use social media. The vast majority watch their children, grandchildren and young employees use mobile devices constantly – and they bemoan all the activity on YouTube, Facebook, Instagram and Twitter – or for the most part even Linked-in. But they don’t actually USE these products. They don’t post information. They don’t set up and follow channels. They don’t connect with people, share information, exchange photos or tell stories on social media. Truthfully, they ignore these trends in their own lives. Which leaves them woefully inept at figuring out how to change their company marketing so it can be more relevant.

The trend is obvious. The answer, equally so. Any modern marketer should be an avid user of social media. Most network heads and media leaders are farther removed from social media than the Pope! They don’t constantly download entertainment, and exchanging with others on all the platforms. They can’t manage the use of these channels when they don’t have a clue how they work, or how other people use them, or understand why they are actually really valuable tools.

Are you using these modern tools? Are you actually living, breathing, participating in the trends? Or are you, like these outdated execs, biding your time wasting money on old programs while you look forward to retirement? And likely killing your company.

When trends emerge it is imperative we become part of that trend. You can’t simply observe it, because your biases will lead you to hope the trend reverts as you continue doing more of the same. A leader has to adopt the trend as a leader, be a practicing participant, and learn how that trend will make a substantial difference in the business. And then apply some vision to remain relevant and successful.

by Adam Hartung | Nov 28, 2014 | Current Affairs, Innovation, Leadership, Web/Tech

Last week I gave 1,000 VHS video tapes to Goodwill Industries. These had been accumulated through 30 years of home movie watching, including tapes purchased for entertaining my 3 children.

It was startling to realize how many of these I had bought, and also surprising to learn they were basically valueless. Not because the content was outdated, because many are still popular titles. But rather because today the content someone wants can be obtained from a streaming download off Amazon or Netflix more conveniently than dealing with these tapes and a mechanical media player.

It isn’t just a shift in technology that made those tapes obsolete. Rather, a major trend has shifted. We don’t really seek to “own” things any more. We’ve become a world of “renters.”

The choice between owning and renting has long been an option. We could rent video tapes, and DVDs. But even though we often did this, most Boomers also ended up buying lots of them. Boomers wanted to own things. Owning was almost always considered better than renting.

Boomers wanted to own their cars, and often more than one. Auto renting was only for business trips. Boomers wanted to own their houses, and often more than one. Why rent a summer home, when, if you could afford it, you could own one. Rent a boat? Wouldn’t it be better to own your own boat (even if you only use it 10 times/year?)

Now we think very, very differently. I haven’t watched a movie on any hard media in several years. When I find time for video entertainment, I simply download what I want, enjoy it and never think about it again. A movie library seems – well – unnecessary.

As a Boomer, there’s all those CDs, cassette tapes (yes, I have them) and even hundreds of vinyl records I own. Yet, I haven’t listened to any of them in years. It’s far easier to simply turn on Pandora or Spotify – or listen to a channel I’ve constructed on YouTube. I really don’t know why I continue to own those old media players, or the media.

Since the big real estate meltdown many people are finding home ownership to be not as good as renting. Why take such a huge risk, paying that mortgage, if you don’t have to?

That this is a trend is even clearer generationally. Younger people really don’t see the benefit of home ownership, not when it means taking on so much additional debt. Home ownership costs are so high that it means giving up a lot of other things. And what’s the benefit? Just to say you own your home?

Where Boomers couldn’t wait to own a car, young people are far less likely. Especially in, or near, urban areas. The cost of auto ownership, including maintenance, insurance and parking, becomes really expensive. Compared with renting a ZipCar for a few hours when you really need a car, ownership seems not only expensive, but a downright hassle.

And technology has followed this trend. Once we wanted to own a PC, and on that PC we wanted to own lots of data – including movies, pictures, books – anything that could be digitized. And we wanted to own software applications to capture, view, alter and display that data. The PC was something that fit the Boomer mindset of owning your technology.

But that is rapidly becoming superfluous. With a mobile device you can keep all your data in a cloud. Data you want to access regularly, or data you want to rent. There’s no reason to keep the data on your own hard drive when you can access it 24×7 everywhere with a mobile device.

And the same is true for acting on the data. Software as a service (SaaS) apps allow you to obtain a user license for $10-$20/user, or $.99, or sometimes free. Why spend $200 (or a lot more) for an application when you can accomplish your task by simply downloading a mobile app?

So I no longer want to own a VCR player (or DVD player for that matter) to clutter up my family room. And I no longer want to fill a closet with tapes or cased DVDs. Likewise, I no longer want to carry around a PC with all my data and applications. Instead, a small, easy to use mobile device will allow me to do almost everything I want.

It is this mega trend away from owning, and toward a simpler lifestyle, that will end the once enormous PC industry. When I can do all I really want to do on my connected device – and in fact often do more things because of those hundreds of thousands of apps – why would I accept the size, weight, complexity, failure problems and costs of the PC?

And, why would I want to own something like Microsoft Office? It is a huge set of applications which contain dozens (hundreds?) of functions I never use. Wouldn’t life be much simpler, easier and cheaper if I acquire the rights to use the functionality I need, when I need it?

There was a time I couldn’t imagine living without my media players, and those DVDs, CDs, tapes and records. But today, I’m giving lots of them away – basically for recycling. While we still use PCs for many things today, it is now easy to visualize a future where I use a PC about as often as I now use my DVD player.

In that world, what happens to Microsoft? Dell? Lenovo?

The implications of this are far-reaching for not only our personal lives, and personal technology suppliers, but for corporate IT. Once IT managed mainframes. Then server farms, networks and thousands of PCs. What will a company need an IT department to do if employees use their own mobile devices, across common networks, using apps that cost a few bucks and store files on secure clouds?

If corporate technology is reduced to just operating some “core” large functions like accounting, how big – or strategic – is IT? The “T” (technology) becomes irrelevant as people focus on gathering and analyzing information. But that’s not been the historical training for IT employees.

Further, if Salesforce.com showed us that even big corporations can manage something as critical as their customer information in a SaaS environment on mobile devices, is it not possible to imagine accounting and supply chain being handled the same way? If so, what role will IT have at all?

The trend toward renting rather than owning is monumental. It affects every business. But in an ironic twist of fate, it may dramatically reduce the focus on IT that has been so critical for the Boomer generation.

by Adam Hartung | Nov 19, 2014 | Current Affairs, Leadership

Warren Buffett is the famous head of Berkshire Hathaway. Famous because he has made himself a billionaire several times over, and made his investors excellent returns.

Berkshire Hathaway doesn’t really make anything. Rather, it owns companies that make things, or supply services. So when you buy a share of BRK you are actually buying a piece of the companies it owns, and a piece of the over $116B it invests in equities of other public companies from the cash flow of its owned entities.

Over the last decade the value of a share of BRK has increased 149%. Pretty darn good, considering the DJIA (Dow Jones Industrial Average) has only increased 64%, and the S&P 500 69%, in the same time period. So for long-term investors, putting your money with Mr. Buffett would have done more than twice as good as buying one of these leading indices.

For this reason, many investors recommend looking at what Berkshire Hathaway buys in its equity portfolio, and then buying those same stocks. On the face of it, seems smart. “Invest like Warren Buffet” one might say.

But that would be a bad idea. Berkshire Hathaway’s value has little to do with the publicly traded equities it owns. In fact, those holdings may well be a damper on BRKs valuation.

Of that giant portfolio, 4 equities make up 58% of the total holdings. Let’s look at how those have done the last decade:

- American Express (AXP,) about 10% of the portfolio, is up 83%

- Coke (KO,) about 15% of the portfolio, is up 109%

- IBM (IBM,) about 10% of the portfolio, is up 64%

- Wells Fargo (WFC,) nearly 25% of the portfolio) is up 71%

Note – not one of these stocks is up anywhere near as much as Berkshire Hathaway. There is no mathematical formula which one can use to multiply the gains on these stocks and interpret that into an overall value increase of 149%!

There are several other large, well known companies in the Berkshire Hathaway portfolio which have large (millions of shares being held) but lesser percentage positions:

- ExxonMobil (XOM) up 86%

- General Electric (GE) down <26%>

- Proctor & Gamble (PG) up 61%

- USBancorp (USB) up 40%

- USG (USG) down <30%>

- UPS up 24%

- Verizon up 38%

- Walmart up 61%

This is not to say that Berkshire Hathaway has owned all these stocks for 10 years. And, this is not all the portfolio. But it is well known that Mr. Buffett is a long-term investor who eschews short-term trading. And, these are at least randomly representative of the portfolio holdings. So by buying and selling shares at different times, and using various trading strategies, BRK’s returns could be somewhat better than the performance of these stocks. But, again, there is no arithmetic which exists that can turn the returns on these common stocks into the 149% gain which Berkshire Hathaway has achieved.

Simply put, Berkshire Hathaway makes money by doing things that no individual investor could ever accomplish. The cash flow is so enormous that Mr. Buffett is able to make deals that are not available to you, me or any other investor with less than $1B (or more likely $10B.)

When the banks looked ready to melt down in 2008 GE was in a world of hurt for money to shore up problems in its GE Capital unit. When GE went out to raise $12B via a common stock sale it turned to Mr. Buffett to lead the investment. And he did, taking a $6B position. For being so gracious, in addition to GE shares Berkshire Hathaway was able to buy $3B in preferred shares with a guaranteed dividend of 10%! Additionally, Mr. Buffett was given warrants allowing him to buy up to $3B of GE shares for a fixed price of $22.25 per share regardless of the price at which GE was trading. These are what are called “sweeteners” in the financial trade. They greatly reduce the risk on the common stock purchase, and simultaneously dramatically improve the returns.

These “sweeteners” are not available to us average, ordinary investors. And this is critical to understand. Because if someone thought that Mr. Buffett made all that money by being a good stock picker, that someone would be operating on the wrong assumption. Mr. Buffett is a very good deal maker who gets a lot more when making his investments than we get. He can do that because he can move so much money, so quickly. Faster even than any large bank.

Take, for example, the recent deal for Berkshire Hathaway to acquire the Duracell battery business from P&G. Where most of us (individuals or corporations) would have to fork over the $3B that P&G wanted, Berkshire Hathaway can simply give back P&G shares it has long held. By exchanging those shares for Duracell, Berkshire avoids paying any tax on the stock gains – thus using P&G shares in its portfolio as a currency to buy the battery business with pre-tax dollars rather than the after-tax dollars the rest of us would have to put up. In a nutshell, that saves at least 35%. But, beyond that, the deal also allows P&G to sell Duracell without having to pay tax on the assets from their end of the transaction, saving P&G 35% as well. To make the same deal, any other buyer would have been required to pay a lot more money.

Acquiring Duracell Berkshire gets 100% of another slow-growth but very good cash flow company (like Dairy Queen, Burlington Northern Rail, etc.) and does so at a very favorable price. This deal adds more cash flow to BRK, more assets to BRK, and has nothing to do with whether or not the stocks in its public equity portfolio are outperforming the DJIA or S&P.

This in no way diminishes Berkshire Hathaway, or Mr. Buffett. But it points out that many people have very bad assumptions when it comes to understanding how Mr. Buffett, or rather Berkshire Hathaway, makes money. Berkshire Hathaway is not a mutual fund, and no investor can make a fortune by purchasing common shares in the companies where Mr. Buffett invests.

Berkshire Hathaway is an extremely complicated company, and deep in its core it is an institution that has a tremendous understanding of financial instruments, financial markets, tax laws and risk. It has long owned insurance companies, and its leaders understand actuarial tables as well as how to utilize complex financial instruments and sophisticated tax opportunities to reduce risk, and raise returns, on deals that no one else could make.

By maximizing cash flow from its private holdings the Berkshire Hathaway constantly maintains a very large cash pool (currently some $60B) which it can move very, very quickly to make deals nobody, other than some of the largest private equity pools, could obtain.

The process by which Berkshire Hathaway decides to buy, hold or sell any security is unique to Berkshire Hathaway. The size of its transactions are enormous, and where we as individuals buy shares by the hundreds (the old “round lot,”) Berkshire buys millions. What stocks Berkshire Hathaway chooses to buy, hold or sell has much more to do with the unique situation of Berkshire Hathaway than stock price forecasts for those companies.

It is a myth for an individual investor to think they could invest like Mr. Buffett, and trying to emulate his returns by emulating the Berkshire portfolio is simply unwise.

by Adam Hartung | Nov 12, 2014 | Current Affairs, Defend & Extend, In the Swamp, In the Whirlpool, Leadership

We see it all too often. A successful business seems to lose its way. Somehow, after decades of success, its results soften, then tumble and the company becomes a victim of its competition. We scratch our heads and wonder, “why did that happen?”

Pizza Hut is well on its way to disappearing. Kind of like Pizza Inn, A&W and Howard Johnson’s. And that seems kind of remarkable considering the company at one time defined pizza for most Americans. From a fast growing franchise in the 1960s to a high profile acquisition by PepsiCo in the 1970s, to anchoring the Yum Brands spin out from PepsiCo in 1997, Pizza Hut just finished 8 straight quarters of declining same store sales. Pizza Hut was once a concept as hot as Apple Stores, but now it looks more like Sears. How could this happen?

When Pizza Hut was growing it locked in on its success formula. And one of the biggest Lock-ins was its name. Pizza Hut was a place where you ate pizza, and the buildings all looked the same with that hut-like red roof. At a time when few Americans outside the northeast ate pizza, this Wichita, Kansas founded (and headquartered until the 1990s) company told people what a pizzeria should look like, and what you should eat.

The company was ardent about controlling what franchisees served. No nachos, or other trendy foods, because they didn’t fit the pizza theme. No delivery, because good pizza required you eat it immediately from the oven. Pizza should be thick and hearty, even served in a deep dish so you have plenty of bread and feel really full. Whether anyone in Italy ever a pizza anything like this really did not matter.

And Pizza Hut would help guide customers as to what toppings they wanted — and usually there should be at least 3 – by offering pre-designed pizzas with names like “meat lovers,” “supreme,” “super supreme” or “veggie lover’s” so an uninformed clientele (originally prairie state, then midwestern, then expanding into the southwest and the south) could buy the product without a lot of fuss.

This success formula may sound cliche today, but it worked. And it worked really well for 30 years, then pretty well for another 10-15. But, eventually, doing the same thing over, and over, and over, and over had less appeal. Almost everyone in the country knew what a Pizza Hut was, what the stores looked like and what the product was like. Competitors came along by the dozens with all kinds of variations, and different kinds of service – like being in a mall, or delivering the product. Inevitably this competition led to price wars. To keep customers Pizza Hut had to lower its prices, even offering 2 pizzas for the price of one. Pizza Hut never lost track of its success formula, and never stopped doing what once made it great. But margins eroded, and then sales started declining.

Lots of people don’t care about Pizza Hut any more. They want an alternative. An alternative product, like California Pizza Kitchen or Wolfgang Pucks. Or an alternative to pizza altogether like the new “fast casual” chains such as Chipotle’s, Baja Fresh or Panera. For a whole raft of reasons, people decided that although they once ate Pizza Hut (even ate a LOT of it) they were going to eat something else.

But Pizza Hut was locked in. First, its name. Pizza. Hut. To fulfill the “brand promise” of that name everything about that store is pre-designed. From the outside to the inside tables to the equipment in the kitchen. 6,300 stores that are almost identical. Any change and you have to make 6,300 changes. Adding new product categories means reprinting 126,000 menus, changing 6,300 kitchen layouts, buying 6,300 new ovens, figuring out the service utensils for 6,300 wait staff. That’s lock-in. Making any change is so hard that the incentive is entirely toward improve what you’ve always done rather than doing something new.

Growth Stalls are Deadly

Eventually, like Pizza Hut, growth stalls. It only takes 2 quarters of declining sales to hit a growth stall, and when that happens less than 7% of businesses will ever again consistently grow at a meager 2%. Growth stalls tell us “hey, the market shifted. What you’re doing isn’t selling any more.”

But most management teams don’t think about a market shift, and instead react by trying to do more of the same. They treat this like its an operational problem. More quality campaigns, more money spent on advertising, more promotions, asking employees to work a little harder, more product for the same (or lower) price – more, better, faster, cheaper. But this doesn’t work, because the problem lies in a market shift away from your “core” that requires an entirely different strategy.

Because management is incented to ignore this shift as long as possible, the company soon becomes irrelevant. Customers know they’ve been going to competitors, and they start to realize it’s been a long time since they bought from that old supplier. They realize their interest in that old company and its products has simply gone away. They don’t pay attention to the ads. And they don’t have any interest in new product announcements. Actually, they find the company irrelevant. Even when the discounts are big, they don’t buy. They do business where they identify with the company and its products, even when those products cost more.

And thus the results start to tumble horribly. Only by now management is so far removed from market trends that it has no idea how to regain relevancy. In Pizza Hut’s case, leadership is undertaking what they’d like to think is a brand overhaul that will change its position in customers’ minds. But, unfortunately, they are doing the ultimate in defend & extend management to try and save the old success formula.

Pizza Hut is introducing a maze of new ways to have its old product, in its old stores. 10 crust choices, 6 sauce choices, 22 of those pre-designed pizza offerings, 5 different liquids you can have dribbled over the pizza, and a rash of exotic new toppings – like banana. So now you can order your pizza 1,000 different ways (actually, more like 10,000.) Oh, and this is being launched with a big increase in traditional advertising. In other words, an insane implementation of what the company has always done; giving customers an American style pizza, in a hut, promoted on TV – even most likely buying what is now considered iconic – a Super Bowl ad.

Yum Brands investors have reasons to be concerned. Pizza Hut is really important to sales and earnings. But its leaders are intent on doing more of the same, even though the market has already shifted. The prognosis does not look good.

by Adam Hartung | Nov 3, 2014 | Current Affairs, In the Rapids, Leadership, Web/Tech

On April 15 Zebra Technologies announced its planned acquisition of Motorola’s Enterprise Device Business. This was remarkable because it represented a major strategic shift for Zebra, and one that would take a massive investment in products and technologies which were wholly new to the company. A gutsy play to make Zebra more relevant in its B-2-B business as interest in its “core” bar code business was declining due to generic competition.

Last week the acquisition was completed. In an example of Jonah swallowing the whale, Zebra added $2.5B to annual revenues on its old base of $1B (2.5x incremental revenue,) an additional 4,500 employees joined its staff of 2,500 and 69 new facilities were added. Gulp.

As CEO Anders Gustafsson told me, “after the deal was agreed to I felt like the dog that caught the car. ”

Fortunately Zebra has a plan, and it is all around growth. Acquisitions led by private equity firms, hedge funds or leveraged buyout partners are usually quick to describe the “synergies” planned for after the acquisition. Synergy is a code word for massive cost cutting (usually meaning large layoffs,) selling off assets (from buildings to product lines and intellectual property rights) and shutting down what the buyers call “marginal” businesses. This always makes the company smaller, weaker and less likely to survive as the new investors focus on pulling out cash and selling the remnants to some large corporation.

There is no growth plan.

But Zebra has publicly announced that after this $3.25B investment they plan only $150M of savings over 2 years. Which means Zebra’s management team intends to grow what they bought, not decimate it. What a novel, or perhaps throwback, idea.

Minimal cost cutting reflects a deal, as CEO Gustafsson told me, “envisioned by management, not by bankers.”

Zebra’s management knew the company was frequently pitching for new work in partnership with Motorola. The two weren’t competitors, but rather two companies working to move their clients forward. But in a disorganized, unplanned way because they were two totally different companies. Zebra’s team recognized that if this became one unit, better planning for clients, the products could work better together, the solutions more directly target customer needs and it would be possible to slingshot forward ahead of competitors to grow revenues.

As CEO since 2007, Anders Gustafsson had pushed a strategy which could grow Zebra, and move the company outside its historical core business of bar code printers and readers. The leadership considered buying Symbol Technology, but wasn’t ready and watched it go to Motorola.

Then Zebra’s team knuckled down on their strategy work. CEO Gustafsson spelled out for me the 3 trends which were identified to build upon:

- Mobility would continue to be a secular growth trend. And business customers needed products with capabilities beyond the generic smart phone. For example, the kind of integrated data entry and printing device used at a remote rental car return. These devices drive business productivity, and customers hunger for such solutions.

- From the days of RFID, where Zebra was an early player, had emerged automatic data capture – which became what now is commonly called “The Internet of Things” – and this trend too had far to extend. By connecting the physical and digital worlds, in markets like retail inventory management, big productivity boosts were possible in formerly moribund work that added cost but little value.

- Cloud-based (SaaS and growth of lightweight apps) ecosystems were going to provide fast growth environments. Client need for capability at the employee’s (or their customer’s) fingertips would grow, and those people (think distributors, value added resellers [VARs]) who build solutions will create apps, accessible via the cloud, to rapidly drive customer productivity.

With this groundwork, the management team developed future scenarios in which it became increasingly clear the value in merging together with Motorola devices to accelerate growth. According to CEO Gustafsson, “it would bring more digital voice to the Zebra physical voice. It would allow for more complete product offerings which would fulfill critical, macro customer trends.”

But, to pull this off required selling the Board of Directors. They are ultimately responsible for company investments, and this was – as described above – a “whopper.”

The CEO’s team spent a lot of time refining the message, to be clear about the benefits of this transaction. Rather than pitching the idea to the Board, they offered it as an opportunity to accelerate strategy implementation. Expecting a wide range of reactions, they were not surprised when some Directors thought this was “phenomenal” while others thought it was “fraught with risk.”

So management agreed to work with the Board to undertake a thorough due diligence process, over many weeks (or months it turned out) to ask all the questions. A key executive, who was a bit skeptical in her own right, took on the role of the “black hat” leader. Her job was to challenge the many ideas offered, and to be a chronic skeptic; to not let the team become enraptured with the idea and thereby sell themselves on success too early, and/or not consider risks thoroughly enough. By persistently undertaking analysis, education led the Board to agree that management’s strategy had merit, and this deal would be a breakout for Zebra.

Next came completing financing. This was a big deal. And the only way to make it happen was for Zebra to take on far more debt than ever in the company’s history. But, the good news was that interest rates are at record low levels, so the cost was manageable.

Zebra’s leadership patiently met with bankers and investors to overview the market strategy, the future scenarios and their plans for the new company. They over and again demonstrated the soundness of their strategy, and the cash flow ability to service the debt. Zebra had been a smaller, stable company. The debt added more dynamism, as did the much greater revenues. The requirement was to decide if the strategy was soundly based on trends, and had a high likelihood of success. Quickly enough, the large shareholders agreed with the path forward, and the financing was fully committed.

Now that the acquisition is complete we will all watch carefully to see if the growth machine this leadership team created brings to market the solutions customers want, so Zebra can generate the revenue and profits investors want. If it does, it will be a big win for not only investors but Zebra’s employees, suppliers and the communities in which Zebra operates.

The obvious question has to be, why didn’t Motorola do this deal? After all, they were the whale. It would have been much easier for people to understand Motorola buying Zebra than the gutsy deal which ultimately happened.

Answering this question requires a lot more thought about history. In 2006 Motorola had launched the Razr phone and was an industry darling. Newly minted CEO Ed Zander started partnering with Google and Apple rather than developing proprietary solutions like Razr. Carl Icahn soon showed up as an activist investor intent on restructuring the company and pulling out more cash. Quickly then-CEO Ed Zander was pushed out the door. New leadership came in, and Motorola’s new product introductions disappeared.

Under pressure from Mr. Icahn, Motorola started shrinking under direction of the new CEO. R&D and product development went through many cuts. New product launches simply were delayed, and died. The cellular phone business began losing money as RIM brought to market Blackberry and stole the enterprise show. Year after year the focus was on how to raise cash at Motorola, not how to grow.

After 4 years, Mr. Icahn was losing money on his position in Motorola. A year later Motorola spun out the phone business, and a year after that leadership paid Mr. Icahn $1.2B in a stock repurchase that saved him from losses. The CEO called this buyout of Icahn the “end of a journey” as Mr. Icahn took the money and ran. How this benefited Motorola is – let’s say unclear.

But left in Icahn’s wake was a culture of cut and shred, rather than invest. After 90 years of invention, from Army 2-way radios to police radios, from AM car radios to home televisions, the inventor analog and digital cell towers and phones, there was no more innovation at Motorola. Motorola had become a company where the leaders, and Board, only thought about how to raise cash – not deploy it effectively within the corporation. There was very little talk about how to create new markets, but plenty about how to retrench to ever smaller “core” markets with no sales growth and declining margins. In September of this year long-term CEO Greg Brown showed no insight for what the company can become, but offered plenty of thoughts on defending tax inversions and took the mantle as apologist for CEOs who use financial machinations to confuse investors.

Investors today should cheer the leadership, in management and on the Board, at Zebra. Rather than thinking small, they thought big. Rather than bragging about their past, they figured out what future they could create. Rather than looking at their limits, they looked at the possibilities. Rather than giving up in the face of objections, they studied the challenges until they had answers. Rather than remaining stuck in their old status quo, they found the courage to become something new.

Bravo.

by Adam Hartung | Oct 28, 2014 | Current Affairs, Defend & Extend, Food and Drink, In the Swamp, Leadership, Lock-in, Television

I’m a “Boomer,” and my generation could have been called the Coke generation. Our parents started every day with a cup of coffee, and they drank either coffee or water during the day. Most meals were accompanied by either water, or iced tea.

But our generation loved Coca-Cola. Most of our parents limited our consumption, much to our frustration. Some parents practically refused to let the stuff in the house. In progressive homes as children we were usually only allowed one, or at most two, bottles per day. We chafed at the controls, and when we left home we started drinking the sweet cola as often as we could.

It didn’t take long before we supplanted our parent’s morning coffee with a bottle of Coke (or Diet Coke in more modern times.) We seemingly could not get enough of the product, as bottle size soared from 8 ounces to 12 to 16 and then quarts and eventually 2 liters! Portion control was out the window as we created demand that seemed limitless.

Meanwhile, Americans exported our #1 drink around the world. From 1970 onward Coke was THE iconic American brand. We saw ads of people drinking Coke in every imaginable country. International growth seemed boundless as people from China to India started consuming the irresistible brown beverage.

My how things change. Last week Coke announced third quarter earnings, and they were down 14%. The CEO admitted he was struggling to find growth for the company as soda sales were flat. U.S. sales of carbonated beverages have been declining for a decade, and Coke has not developed a successful new product line – or market – to replace those declines.

Coke is a victim of changing customer preferences. Once a company that helped define those preferences, and built the #1 brand globally, Coke’s leadership shifted from understanding customers and trends in order to build on those trends towards defending & extending sales of its historical product. Instead of innovating, leadership relied on promotion and tactics which had helped the brand grow 30 years ago. They kept to their old success formula as trends shifted the market into new directions.

Coke began losing its relevancy. Trends moved in a new direction. Healthfulness led customers to decide they wanted a less calorie rich, nutritionally starved drink. And concerns grew over “artificial” products, such as sweeteners, leading customers away from even low calorie “diet” colas.

Meanwhile, younger generations started turning to their own new brands. And not just drinks. Instead of holding a Coke, increasingly they hold an iPhone. Where once it was hip to hang out at the Coke machine, or the fountain stand, now people would rather hang out at a Starbucks or Peet’s Coffee. Where once Coke was identified and matched the aspirations of the fast growing Boomer class, now it is replaced with a Prada handbag or other accessory from an LVMH branded luxury product.

Where once holding a Coke was a sign of being part of all that was good, now the product is largely passe. Trends have moved, and Coke didn’t. Coke leadership relied too much on its past, and failed to recognize that market shifts could affect even the #1 global brand. Coke leaders thought they would be forever relevant, just do more of what worked before. But they were wrong.

Unfortunately, CEO Muhtar Kent announced a series of changes that will most likely further hurt the Coca-Cola company rather than help it.

First, and foremost, like almost all CEOs facing an earnings problem the company will cut $3B in costs. The most short-term of short-term actions, which will do nothing to help the company find its way back toward being a prominent brand-leading icon. Cost cuts only further create a “hunker-down” mindset which causes managers to reduce risk, rather than look for breakthrough products and markets which could help the company regain lost ground. Cost cutting will only further cause remaining management to focus on defending the past business rather than finding a new future.

Second, Coca-Cola will sell off its bottlers. Interestingly, in the 1980s CEO Roberto Goizueta famously bought up the distributorships, and made a fortune for the company doing so. By the year 2000 he was honored, along with Jack Welch of GE, as being one of the top 2 CEOs of the century for his ability to create shareholder value. But now the current CEO is selling the bottling operations – in order to raise cash. Once again, when leadership can’t run a business that makes money they often sell off assets to generate cash and make the company smaller – none of which benefits shareholders.

Third, fire the Chief Marketing Officer. Of course, somebody has to be blamed! The guy who has done the most to bring Coca-Cola’s brand out of traditional advertising and promote it in an integrated manner across all media, including managing successful programs for the Olympics and World Cup, has to be held accountable. What’s missing in this action is that the big problem is leadership’s fixation with defending its Coke brand, rather than finding new growth businesses as the market moves away from carbonated soft drinks. And that is a problem that requires the CEO and his entire management team to step up their strategy efforts, not just fire the leader who has been updating the branding mechanisms.

Coca-Cola needs a significant strategy shift. Leadership focused too long on its aging brands, without putting enough energy into identifying trends and figuring out how to remain relevant. Now, people care a lot less about Coke than they did. They care more about other brands, like Apple. Globally. Unless there is a major shift in Coke’s strategy the company will continue to weaken along with its primary brand. That market shift has already happened, and it won’t stop.

For Coke to regain growth it needs a far different future which aligns with trends that now matter more to consumers. The company must bring forward products which excite people ,and with which they identify. And Coke’s leaders must move much harder into understanding shifts in media consumption so they can make their new brands as visible to newer generations as TV made Coke visible to Boomers.

Coke is far from a failed company, but after a decade of sales declines in its “core” business it is time leadership realizes takes this earnings announcement as a key indicator of the need to change. And not just simple things like costs. It must fundamentally change its strategy and markets or in another decade things will look far worse than today.

by Adam Hartung | Oct 21, 2014 | Current Affairs, Innovation, Leadership

“Where was the Board of Directors?”

That is one of the questions I am asked most frequently. And it’s a good one. Readers, and audiences, wonder how a well-educated and experienced Board could allow a company – like Blockbuster, Hostess, Radio Shack, Sears, Circuit City and Blackberry, to name a few – to fall into bankruptcy, or a situation where the future looks dismal, perhaps impossible.

Isn’t the Board accountable for company strategy, performance and the decisions made by the CEO? Perhaps, but they often haven’t acted like it.

Powerless Past

Historically Boards of Directors reviewed a company strategy once per year, and it was far from a discussion. The CEO, perhaps along with his/her top few executives, would present a multi-page document, attaching ample appendices including elaborate spreadsheets and charts. This would be a one-way presentation to the Board, overviewing recent performance, past strategy and management’s view of the future strategy.

There might have been polite discussion, but the Board only had one available action, either approve the strategy, or reject it. Given that Boards had no ability to create their own strategy, and rarely much data to contradict the mountain of statistics presented by management, the vote was a given – out came the “rubber stamp” of approval. All orchestrated by an “Imperial CEO” who rarely wanted discussion, or anything other than quick approval.

A Call For Change

Facing mounting investor concerns about strategic guidance and the Board’s role, the increasing involvement of activist investors willing to replace Board members, and the long arm of enhanced regulation the National Association of Corporate Directors (NACD) created a Blue Ribbon Commission to review the Board’s role in setting corporate strategy. Co-Chaired by Ray Gilmartin (former Chair and CEO of Becton Dickinson and Merck, Board member of Microsoft and General Mills, HBS ’68) and Maggie Wilderotter (Chair and CEO of Frontier Communications, Board member Procter & Gamble and Xerox) and containing 21 diverse business leaders, this commission just published “The NACD Blue Ribbon Commission Report on Strategy Development.”

This report makes 10 specific recommendations regarding Board involvement in corporate strategy, which in total represent a substantial change in how often, and how deeply, Boards discuss and alter strategy in conjunction with management. The report calls for greater accountability by the Board, increased transparency from management and the requirement for better strategy development.

A New, More Controversial Involvement by Boards of Directors

In an interview, Dr. Raetha King, Chair of NACD (former Board member Exxon Mobil, Wells Fargo, HB Fuller, Lenox Group and General Mills Foundation) said “it is time for Boards to change their approach regarding strategy formulation toward ‘shape and monitor.’ Boards must move from a passive role to a more active role. The Board must be fully engaged, at all times, with strategy.”

When asked what has prompted this significant recommendation, Dr. King went on to say “This report was deeply influenced by the external disruptions which are happening to companies on a regular basis in today’s dynamic markets. Boards are too often blindsided by external events, as is management. The solution is a fundamental change in the strategy process to engage the Board earlier, and more often. To have Boards participate in the strategy process, and not merely approve a finished product. The Board must become a strategic asset for the CEO and his executive team by engaging all members, and their cognitive diversity, for insight and direction.”

Recognizing and Managing Disruption

Co-chair Ray Gilmartin has been a professor at the Harvard Business School, and a colleague of fellow professor and famed innovation guru Dr. Clayton Christensen. He has observed how disruptive innovations have affected many companies, and has asked Dr. Christensen to provide Boards with advice on how to avoid becoming stuck in the “Innovator’s Dilemma.” Mr. Gilmartin offered “The NACD’s Blue Ribbon Commission report on strategy is intended to help corporate directors and their boards prepare for the unpredictable, even the unthinkable. More specifically, the report is intended to evolve director’s strategy development role from the typical ‘review and concur’ to a higher level of year-round engagement in the strategy development process.”

This is a remarkable change in Board involvement, well beyond anything previously recommended by any association or other body which works with corporate Boards. And the impact should be widely felt, as NACD has 14,000 members, all belonging to Boards. By recommending that Boards re-allocate their time to spend more on strategy discussion, and less on historical results and reviews of well-known practices, this commission is pushing for a sea change in the strategy process.

Changed Role for the CEO, and the Board

Co-chair Maggie Wilderotter has the view not only of an outside director, but as someone currently holding both CEO and Chair positions in a company. She completely concurred with her commission colleagues. In our interview she commented “Historically, strategy was not dynamic. Now it must be, due to so many marketplace changes happening so quickly. It is critical that the CEO utilize the Board to re-assess strategy at each Board meeting so as to better prepare for changes and avoid incurring any additional marketplace risk.”

She continued “The new best practice, today, is for management to draft the strategy, but not finalize it. Options must be posited and discussed. Yes, the CEO must own the strategy, and the strategy development process. And part of that process is to drive discussion with not only internal management but external leaders on the Board. It is critical companies track more trends from outside the company, add more external inputs to the data, and be increasingly aware of how the external world impacts the company. Good execution today involves connecting internal metrics to external markets.”

This will involve quite a bit of change in Board dynamics. Many CEOs, as mentioned above, may not be prepared for such a radical shift in the strategy development process. To address this Ms. Wilderotter recommends “Board members must pressure the Chairman and/or Lead Director for updates on strategy before documents are made final, and before final decisions are made. Members must resist accepting final documents, and insist on receiving interim information. Members must constantly push for management to supply not only internal information, but external data on trends, competitors, customers and all factors that could impact future performance. There must be a proactive conversation on the new expectations directors have about management engaging them in the strategy development process. And Board members must insist on Executive Sessions, apart from management, to discuss strategy amongst themselves and develop feedback for the CEO.”

The report pulls no punches in its strong recommendations for changing the Board’s involvement in strategy. And the degree to which the report, and its authors, identify the importance of disruptive change on company performance today is eye opening. The report’s first recommendation sets the tone for significant change:

“Expect change and understand how it may affect the company’s current strategic course, potentially undermining the fundamental assumptions on which the strategy rests.”

Is this the end of the “Imperial CEO?” Readers know I have long called for greater transparency and more Board involvement in challenging CEOs where the strategy does not align with market realities. This report seeks the same thing. Boards can no longer allow the failure of management, or overly rely on a dictatorial CEO, on something as important as corporate strategy. They owe too much to the investors, employees, suppliers and communities in which their organizations operate.

As readers of my book and this blog know, this has long been my mantra. Like Dr. Christensen, I too encourage leaders to open their eyes to the extent which disruption affects their organizations in my columns, my keynote speeches and workshops. No longer is excellent execution enough. In a world where technologies, regulations, customers, products and competitors change so quickly strategy must be reviewed and updated constantly. And this report, from a noteworthy organization and blue ribbon panel, is a clear call for Boards to sink their teeth deeper into strategy.

All Board members, and people who want to be on Boards, should seek out a copy of this report, read it and share it with executives and Board members across your networks. These are recommendations which can have a profound impact on future performance in our rapidly changing world.

[Update 10-28-2014 — NACD has released a summary of the report. Follow this link to read all 10 recommendations and become better informed.]

by Adam Hartung | Oct 15, 2014 | Current Affairs, Defend & Extend, Innovation, Leadership

The Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA) is down 400 points today. Down 8% since its high 3 weeks ago, and now showing no gains for the entire year.

Oh my!

There seems little immediate explanation for the fast drop. When major financial news outlets say it is caused by Ebola fears you can be assured those being asked “why” are clutching at straws. They have no clear explanation. This could be nothing more than a 10% correction, a short-term break in the long-term bull which has gone on for a remarkable 3 years.

But, investors are not out of the woods. Will the market continue to even greater highs? Will this Bull market continue for many more months?

There is at least one good reason investors should be concerned.

For the last decade, corporations have been about the biggest buyers of equities. Since 1998 85% of all corporate earnings have gone into share buyback programs. Buybacks do not add value to a company, they merely reduce the number of shares. By reducing the number of outstanding shares, earnings per share (EPS) can go up, even if earnings do not go up. But reducing the denominator the answer increases, even if the numerator does not change – or goes up only slightly. Thus per share earnings have increased, on average, 6.2% quarterly – more than double the revenue increase of only 2.6%. All artificial growth – not a true increase in corporate performance.

In 2014 95% of S&P 500 corporate earnings will go toward buybacks and dividends – in effect increasing investor returns while doing nothing to make the companies better. In the 1st quarter money paid to investors exceeded S&P 500 profits, and likely will do so again in the 3rd quarter. All of which props up stocks in the short-term, but removes cash from the companies. Cash which could be used to invest in growing revenues long-term.

This is not new. In the last decade, cash for buybacks has doubled. Today, 30% of free cash flow goes into stock repurchases, a rate double that of 2002.

Meanwhile investment in plant and equipment has declined from over 50% of cash flow to under 40%. Today the average age of plant and equipment in the USA is 22 years – the oldest it has been since 1956! In an era of almost free money – with interest rates in low single digits and often less than inflation – corporations are taking on debt NOT to invest in growth, but rather to simply pay out more to shareholders in efforts to prop up stock prices. And they’ve done it now for so long – over a decade – that the short-term has become the long-term, and there is precious little invested base from which future revenues and profits can grow.

Leaders for the past several years have failed their investors by not investing cash flow in innovation for long-term growth. Instead of new products creating new markets, the only innovations being funded have been focused solely on defending and extending past product sales. With an inordinate fear of risk, and a complete lack of future vision, what passes for innovation are attempts to sustain the old stuff rather than create something new.

For example, P&G’s leaders gave investors the “Basic” line of products. These were literally less good products, a throwback to earlier quality levels, repackaged and sold at a lower price. The last really “new” product from P&G was the Swiffer mop – and that was back in 1999. Since then we’ve had what seems to be infinite variations of that product, all intended to extend its life. Where’s the new “great thing” that will jump revenues and sustain profits for years into the future?

There are exceptions to this generalization. Of course Facebook is changing media and advertising, while Netflix is redeveloping how we enjoy entertainment. Amazon has us buying on-line instead of in retail stores, and wondering if we’ll someday receive same-day shipping via drones. And Apple has moved us into the world of apps encouraging us to buy smartphones and tablets while dumping land-lines, cell phones and PCs. So there are some serious innovators out there.

But, for long-term investors overall, there is a big reason to worry. This DJIA drop may be merely a “normal 10% correction.” But, equities cannot go up forever on declining cash flow from ancient investments of previous leaders and interest-free debt accumulation. For equities to continue their upward trajectory at some time companies have to launch new products, create new markets and generate sustainable long-term profits. In other than a handful of noteworthy companies, there isn’t much of this kind of investment happening today – or over the last 10-15 years.

Eventually, costs of capital will go up. And cash flow from old investments will go down. If there aren’t real sales growth opportunities there could be declining real profits. Without buybacks to feed the bull, a raging bear could overtake the scene.

Oh my.