by Adam Hartung | Mar 28, 2017 | In the Rapids, Innovation, Investing, Leadership

(Photo: General Electric CEO Jeffrey Immelt, ERIC PIERMONT/AFP/Getty Images)

General Electric stock had a small pop recently when investors thought CEO Jeffrey Immelt might be pushed out. Obviously more investors hope the CEO leaves than stays. And it appears clear that activist investor Nelson Peltz of Trian Partners thinks it is time for a change in CEO atop the longest running member of the Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA.)

You can’t blame investors, however. Since he took over the top job at General Electric in 2001 (16 years ago) GE’s stock value has dropped 38%. Meanwhile, the DJIA has almost doubled. Over that time, GE has been the greatest drag on the DJIA, otherwise the index would be valued even higher! That is terrible performance — especially as CEO of one of America’s largest companies.

But, after 16 years of Immelt’s leadership, there’s a lot more wrong than just the CEO at General Electric these days. As the JPMorgan Chase analyst Stephen Tusa revealed in his analysis, these days GE is actually overvalued, “cash is weak, margins/share of customer wallet are already at entitlement, the sum of the parts valuation points to a low 20s stock price.” He goes on to share his pessimism in GE’s ability to sell additional businesses, or create cost lowering synergies or tax strategies.

Former Chairman and CEO of General Electric Jack Welch. (AP Photo/Richard Drew)

What went so wrong under Immelt? Go back to 1981. GE installed Jack Welch as its new CEO. Over the next 20 years there wasn’t a business Neutron Jack wouldn’t buy, sell or trade. CEO Welch understood the importance of growth. He bought business after business, in markets far removed from traditional manufacturing, building large positions in media and financial services. He expanded globally, into all developing markets. After businesses were acquired the pressure was relentless to keep growing. All had to be no. 1 or no. 2 in their markets or risk being sold off. It was growth, growth and more growth.

Welch’s focus on growth led to a bigger, more successful GE. Adjusted for splits, GE stock rose from $1.30 per share to $46.75 per share during the 20 year Welch leadership. That is an improvement of 35 times – or 3,500%. And it wasn’t just due to a great overall stock market. Yes, the DJIA grew from 973 to 10,887 — or about 10.1 times. But GE outperformed the DJIA by 3.5 times (350%). Not everything went right in the Welch era, but growth hid all sins — and investors did very, very, very well.

Under Welch, GE was in the rapids of growth. Welch understood that good operating performance was not enough. GE had to grow. Investors needed to see a path to higher revenues in order to believe in long term value creation. Immediate profits were necessary but insufficient to create value, because they could be dissipated quickly by new competitors. So Welch kept the headquarters team busy evaluating opportunities, including making some 600 acquisitions. They invested in things that would grow, whether part of historical GE, or not.

Jeff Immelt as CEO took a decidedly different approach to leadership. During his 16 year leadership GE has become a significantly smaller company. He sold off the plastics, appliances and media businesses — once good growth providers — in the name of “refocusing the company.” Plans currently exist to sell off the electrical distribution/grid business (Industrial Solutions) and water businesses, eliminating another $5 billion in annual revenue. He has dismantled the entire financial services and real estate businesses that created tremendous GE value, because he could not figure out how to operate in a more regulated environment. And cost cutting continues. In the GE Transportation business, which is supposed to remain, plans have been announced to double down on cost cutting, eliminating another 2,900 jobs.

Under Immelt GE has focused on profits. Strategy turned from looking outside, for new growth markets and opportunities, to looking inside for ways to optimize the company via business sales, asset sales, layoffs and other cost cutting. Optimizing the business against some sense of an historical “core” caused nearsighted — and shortsighted — quarterly actions, financial gyrations and transactions rather than building a sustainable, growing revenue stream. Under Immelt sales did not just stagnate, sales actually declined while leadership pursued higher margins.

By focusing on the “core” GE business (as defined by Immelt) and pursuing short term profit maximization, leadership significantly damaged GE. Nobody would have ever imagined an activist investor taking a position in Welch’s GE in an effort to restructure the company. Its sales growth was so good, its prospects so bright, that its P/E (price to earnings) multiple kept it out of activist range.

But now the vultures see the opportunity to do an even bigger, better job of whacking up GE — of tearing it into small bits while killing off all R&D and innovation — like they did at DuPont. Over 16 years Immelt has weakened GE’s business — what was the most omnipresent industrial company in America, if not the world – to the point that it can be attacked by outsiders ready to chop it up and sell it off in pieces to make a quick buck.

Thomas Edison, one of the world’s great inventors, innovators and founder of GE, would be appalled. That GE needs now, more than ever, is a leader who understands you cannot save your way to prosperity, you have to invest in growth to create future value and increase your equity valuation.

In May, 2012 (five years ago) I warned investors that Immelt was the wrong CEO. I listed him as the fourth worst CEO of a publicly traded company in America. While he steered GE out of trouble during the financial crisis, he also simply steered the company in circles as it used up its resources. Then was the time to change CEOs, and put in place someone with the fortitude to develop a growth strategy that would leverage the resources, and brand, of GE. But, instead, Immelt remained in place, and GE became a lot smaller, and weaker.

At this point, it is probably too late to save GE. By losing sight of the need to grow, and instead focusing on optimizing the old business while selling assets to raise cash for reorganizations, Immelt has destroyed what was once a great innovation engine. Now that the activists have GE in their sites it is unlikely they will let it ever return to the company it once was – creating whole new markets by developing new technologies that people never before imagined. The future looks a lot more like figuring out how to maximize the value of each piece of meat as it’s carved off the GE carcass.

by Adam Hartung | Mar 22, 2017 | In the Whirlpool, Investing, Retail

(Photo by Scott Olson/Getty Images)

Traditional retailers just keep providing more bad news. Payless Shoes said it plans to file bankruptcy next week, closing 500 of its 4,000 stores. Most likely it will follow the path of Radio Shack, which hasn’t made a profit since 2011. Radio Shack filed bankruptcy and shut a gob of stores as part of its “turnaround plan.” Then in February Radio Shack filed its second bankruptcy — most likely killing the chain entirely this time.

Sears Holdings finally admitted it probably can’t survive as a going concern this week. Sears has lost over $10 billion since 2010 — when it last showed a profit — and owes over $4 billion to its creditors. Retail stocks cratered Monday as the list of retailers closing stores accelerated: Sears, KMart, Macy’s, Radio Shack, JCPenney, American Apparel, Abercrombie & Fitch, The Limited, CVS, GNC, Office Depot, HHGregg, The Children’s Place and Crocs are just some of the household names that are slowly (or not so slowly) dying.

None of this should be surprising. By the time CEO Ed Lampert merged KMart with Sears the trend to e-commerce was already pronounced. Anyone could build an excel spreadsheet that would demonstrate as online retail grew, brick-and-mortar retail would decline. In the low margin world of retail, profits would evaporate. It would be a blood bath. Any retailer with any weakness simply would not survive this market shift — and that clearly included outdated store concepts like Sears, KMart and Radio Shack which long ago were outflanked by on-line shopping and trendier storefronts.

Yet, not everyone is ready to give up on some retailers. Walmart, for example, still trades at $70 per share, which is higher than it traded in 2015 and about where it traded back in 2012. Some investors still think that there are brick-and-mortar outfits that are either immune to the trends, or will survive the shake-out and have higher profits in the future.

And that is why we have to be very careful about business myths. There are a lot of people that believe as markets shrink the ultimate consolidation will leave one, or a few, competitors who will be very profitable. Capacity will go away, and profits will return. In the end, they believe if you are the last buggy whip maker you will be profitable — so investors just need to pick who will be the survivor and wait it out. And, if you believe this, then you have justified owning Walmart.

Only, markets don’t work that way. As industries consolidate they end up with competitors who either lose money or just barely eke out a small profit. Think about the auto industry, airlines or land-line telecom companies.

Two factors exist which effectively forces all the profits out of these businesses and therefore make it impossible for investors to make money long-term.

First, competitive capacity always remains just a bit too much for the market need. Management, and often investors, simply don’t want to give up in the face of industry consolidation. They keep hoping to reach a rainbow that will save them. So capacity lingers and lingers — always pushing prices down even as costs increase. Even after someone fails, and that capacity theoretically goes away, someone jumps in with great hopes for the future and boosts capacity again. Therefore, excess capacity overhangs the marketplace forcing prices down to break-even, or below, and never really goes away.

Given the amount of retail real estate out there and the bargains being offered to anyone who wants to open, or expand, stores this problem will persist for decades in retail.

Second, demand in most markets keeps declining. Hopefuls project that demand will “stabilize,” thus balancing the capacity and allowing for price increases. Because demand changes aren’t linear, there are often plateaus that make it appear as if demand won’t go down more. But then something changes — an innovation, regulatory change, taste change — and demand takes another hit. And all the hope goes away as profits drop, again.

It is not a successful strategy to try being the “last man standing” in any declining market. No competitor is immune to these forces when markets shift. No matter how big, when trends shift and new forms of competition start growing every old-line company will be negatively affected. Whether fast, or slow, the value of these companies will continue declining until they eventually become worthless.

Nor is it successful long-term to try and segment the business into small groupings which management thinks can be protected. When Xerox brought to market photocopying, small offset press manufacturers (ABDick and Multigraphics ) said not to worry. Xeroxing might be OK in some office installations, but there were customer segments that would forever use lithography. Even as demand shrunk, well into the 1990s, they said that big corporations, industrial users, government entities, schools and other segments would forever need the benefits of lithography, so investors were safe. Today the small offset press market is a tiny fraction of its size in the 1960s. ABDick and Multigraphics both went through rounds of bankruptcies before disappearing. Xerography, its child desktop publishing, and its grandchild electronic screens, killed offset for almost all applications.

So don’t be lured into false hopes by retailers who claim their segment is “protected.” Short-term things might not look bad. But the market has already shifted to e-commerce and this is just round one of change. More and more innovations are coming that will make the need for traditional stores increasingly unnecessary.

Many readers have expressed their disappointment in my chronic warnings about Walmart. But those warnings are no different than my warnings about Sears Holdings. It’s just that the timing may be different. Both companies have been over-investing in assets (brick-and-mortar stores) that are declining in value as they have attempted to defend and extend their old business model. Both radically under-invested in new markets which were cannibalizing their old business. And, in the end, both will end up with the same results.

And this is true for all retailers that depend on traditional brick-and-mortar sales for their revenues and profits — it’s only a matter of when things will go badly, not if. So traditional retail is nowhere that any investor wants to be.

by Adam Hartung | Mar 10, 2017 | Books, Defend & Extend, Employment, Leadership

Harvard Business Review Press just published an insightful new book by two senior partners at Bain & Company, one of the world’s three leading strategy consulting firms, entitled Time Talent Energy. The book’s great insight is that companies utilize a plethora of tools to manage money and financials to the nth degree, but that approach is less successful than putting a greater focus on managing employee time, talent and energy.

Harvard Business Review Press

Harvard Business Review Press

Time Talent Energy jacket cover

While managing financials is required in the modern organization, it is insufficient for success. Mankins and Garton discovered that organizations which focus more heavily on managing how employees spend their time and how they thoughtfully place people in their roles, create companies where employees are inspired and 40% more productive than their competition. And this pays off, with profit margins which are 30-50% higher than their industry average. The improvement is so great from focusing on employees that in today’s low cost and easily accessible capital world it is better to waste some cash in the process of better managing time and talent.

In most companies 25% of all productive time is wasted and can reach as high as 40% in complex organizations. Think of all the emails, texts, voice mails and meetings that absorb vast amounts of time. Yet, as the authors are fond of pointing out, nobody can create a 25 hour day. So if you can recapture that time, productivity will soar. The results are far greater than squeezing another 1% (or even 10%) out of your cost structure. If instead of spending so much time managing costs we spent more time eliminating complexity and unneeded tasks, competitiveness will soar.

Some people think that the best companies hire better people. Surprisingly, this is not true. About 15-16% of employees in every company are “A” players. But most companies squander this talent by spreading it around the organization. To achieve higher productivity and greater success, leading companies cluster their “A” players into teams focused on the most critical, important parts of the business. Thus, the best talent is working side-by-side on the most important challenges which can lead to the greatest gains. This talent clustering energizes the best workers, increasing productivity by 44%. But more than that, as the culture is inspired from building on its own gains productivity soars as much as 125%.

But in most organizations the focus still remains on finance. The CFO is frequently the second most powerful individual, behind only the CEO. The head of Human Resources (Chief Human Resources Officer — CHRO) rarely has the clout of a CFO. And the CFO job is seen as the route to CEO — far more CFOs than CHROs become CEOs. Simultaneously, organizations spend exorbitantly on financial control tools, such as ERP (Enterprise Resource Planning) from companies like Oracle and SAP — while very few have any kind of tool set for effectively managing employee time or talent deployment. The authors conclude it is apparent business leaders have significantly overshot on managing financial resources, while allowing their organization to be woefully incapable of managing its human resources.

I had the opportunity to interview Michael Mankins to obtain some additional insight about managing time, talent and energy:

Adam Hartung: Do businesses need to lessen the CFO role, and heighten the CHRO role?

Michael Mankins: The reality is that most human resource decisions, those that determine how people spend their time, and how talent is deployed, are made by line managers. Made within the bowels of the organization, with little more than senior leadership guidelines. There needs to be significantly more involvement by senior leadership in collecting and reviewing data on critical skills for the organization, “A” player performance and leadership development. If as much time was spent by senior leadership teams discussing human resources as spent on budgets there would be a tremendous improvement in productivity.

The CFO and CHRO should definitely be peers. To do that requires a cultural change from being an organization focused on preserving the status quo, reducing mistakes and keeping leadership out of jail to one that is far more future oriented. This can be done and in the book we highlight companies such as ABInBev, Ford, Nordstrom, Starbucks, IKEA, Netflix and others who have accomplished this.

Hartung: Companies spent enormous sums installing ERP systems and they spend a lot to maintain them. Yet, from reading your book it seems like this may have been misguided.

Mankins: All companies need to be able to change their business model as markets shift. ERP frequently creates a wiring that makes it hard to change with the competitive landscape, or as changes in capability are required. ERP locks in the business model at a point in time — but great performers develop ways to adapt.

All companies need a great general ledger. ERP goes far beyond the general ledger and in doing so can make a company too inflexible for today’s rate of change. There needs to be a flexible ERP system —which just doesn’t seem to exist right now. The ERP market seems ripe for a marketplace disrupter!

Simultaneously there aren’t any great tools out there for collecting data that can help a company reduce complexity and eliminate time wasters. Nor are there great tools for managing the performance of “A” players. The top performing companies do create a discipline around these tasks, collecting and analyzing data. Many companies would be helped by a tool that would do for time and talent management what we’ve done for financial management.

Hartung: You demonstrate that clustering “A” players creates dramatic improvement in productivity and company performance. Do great companies focus these clusters on improving the company as it is, or looking for the next “big thing?”

Mankins: We discovered that by and large the greatest gains come from focusing on the latter. Almost all MBA programs are maniacal about training managers to improve the existing business. For many years corporate planning systems have focused almost entirely on improving the operating model. The result is that in many, many industries leadership has almost no hope of improving operating margins by even 1%. There simply is nothing left to improve which can achieve significant results.

Simultaneously, 1% growth has a far, far greater return on investment than 1% operating margin improvement. So if companies focus their best talent on breakthroughs, in whole new ways of running the business, or creating new markets, the results are significantly greater.

Hartung: Many companies have clustered their top performers into “all star teams.” But this has been met by demotivation of employees not on these teams – feeling like “also rans” or “bench warmers.” And often there is a compensation difference between the all-star team members and others that is demotivating. How do leaders manage this conundrum?

Mankins: If this demotivation is driven by internal competitiveness — by ambition to move up the organization — there is a culture problem. Everyone is not on the same page about company needs and the talent to address those needs. Internal competitiveness should be addressed so everyone wants the company to succeed, so everyone individually can succeed. Rewards, compensation and non-compensation, need to be geared for groups to be motivated, not just individuals.

In the organization, leadership should work hard to make sure everyone knows they are important. There should be an effort to reward the “supporting cast” and not just the main characters. It is true that in today’s world many people have an exaggerated view of their own performance. We address this in the book with recommendations for how to give people feedback so they know the reality of their role and their performance in order to grow and do better. Today most companies have a very poorly performing review and training process, because they tie it to the compensation cycle thus limiting feedback to once per year and, unfortunately, doing feedback at the same time (often the same meeting) as compensation and bonus decisions. Addressing the performance feedback process can go a long way to avoid the demotivation problem.

Hartung: How do companies find “A” players?

Mankins: Search firms are the antithesis of finding “A” players. Their approach, their process, is not designed to deliver “A” candidates. To build a good group of “A” players requires the CEO, CHRO and senior leadership team understand what constitutes an “A” player in their organization. Then they can use the entire organization to seek out people with this behavioral signature in order to recruit them.

It is unfortunate that most company HR processes would not recognize an “A” player if one submitted a resume and would not hire one if they arrived for an interview. Most current processes focus too much on relationships (who candidates know,) narrow skills and prior specific experiences and not enough on what is needed for future success. And hiring decisions are often made by the wrong people; people too low in the organization and people who don’t know the desired behavioral signature. Google is one role model for knowing how to find and develop “A” players.

Unfortunately there is enormous ageism in hiring today. Especially in technology. Employers lack awareness of the value of generalizable experience they can bring into their company. The search for very specific experiences often leads to a very limited list of candidates with narrow experience and too often they do not perform at the “A” level when placed in the context of the new company and new competitive market requirements. Looking more broadly at candidates with great experience, even if not seemingly directly applicable (including candidates in their 50s and 60s) could lead to far greater success.

by Adam Hartung | Feb 28, 2017 | E-Commerce, Employment, real estate, Retail

(Photo: JOHN MACDOUGALL/AFP/Getty Images)

Amazon.com has become an important part of the American economy, and the lives of people globally. But, far too few people still understand the repercussions of Amazon’s success on retailers, consumer goods manufacturers, real estate – and ultimately everyone’s lives. The implications are enormous. Smart leaders, and investors, will plan for these implications and take advantage of the market shift.

Invest in ecommerce, divest traditional retailers.

The first implication is just thinking about investing in Amazon and/or its competitors in retail. In May, 2016 I compared the market value of Wal-Mart, the world’s largest retailer, with Amazon. At the time Wal-Mart was worth $216 billion, and Amazon was worth $332 billion. The difference could be explained by realizing that Wal-Mart was the leader at brick-and-mortar sales, which were shrinking, while Amazon was the leader in e-commerce, which is growing. Since then Wal-Mart’s value has increased to $222 billion – up $6 billion, 2.8%. Meanwhile Amazon’s value has increased to $403 billion- up $71 billion, 21.4%. Over three years (starting 3/3/14) Wal-Mart’s per share value has declined from $74 to $71 (down 4%,) while Amazon’s has risen from $370 to $845 (up 128%.)

To put it mildly, investing in Amazon, which is the leader in e-commerce, has created a great return. Contrastingly that value increase has been fueled by declines in traditional retailers. The Amazon Effect has caused shares in companies like Sears Holdings, JCPenney, Kohl’s, Macy’s and many other stalwarts of the bygone era to be crushed. Over the last year investors in XRT (the retail industry spider) have increased 1.6%, while the S&P 500 spider has jumped 22%. The number of retailers with debt rated at Moody’s most distressed level has tripled since 2009 – and Moody’s predicts this list will worsen over the next five years.

There is vastly too much retail space, and nobody knows what to do with it.

And this has an impact on real estate. As online sales come to over 11% of all holiday sales in 2016, and Amazon accounts for 40% of all those sales, it is clear people just don’t go to stores any more anywhere near the way they once did. Historically prime retail real estate was considered valuable – and in 2007 many people thought Sears real estate was worth more than Sears as a retailer. But no longer. According to Morningstar, Sears store closings alone could cause 200 malls to close.

It is apparent the Amazon Effect has left America with far more storefronts than needed. Stand-alone stores are being shuttered, with no alternative use for most buildings. Malls and shopping centers go begging as traffic drops, tenants leave, lease rates collapse and the facilities end up wholly or nearly empty. This means you don’t want to invest in retail real estate REITs. But it also means that neighborhoods, and sometimes entire towns, will be impacted as these empty buildings reduce interest in housing and push down residential prices.

Tax receipts will fall, and nobody knows how to replace them.

For a long time governments gave handouts to retailers in the form of tax breaks to build stores or locate their headquarters. But as stores close the property tax receipts decline, putting a greater burden on homeowners to pay for schools and infrastructure. Same with sales taxes which disappear from the local government coffers. And tax breaks once given to hold onto jobs – like the ones the village of Hoffman Estates and state of Illinois, gave Sears in 2011 to not move its headquarters, look far less justified. In short, the Amazon Effect has an enormous impact on the local tax base – and those missing dollars will inevitably have to come from residents – or a significant curtailing of services.

The impact on job eliminations will be staggering.

The Amazon Effect also has an impact on jobs. Amazon’s growth keeps escalating, from 19% in 2014 to 20% in 2015 to 28% in 2016, which takes the jobs away from traditional retailers. Macy’s plans to shed 10,000 workers as it shrinks and streamlines. JCPenney will eliminate 6,000 employees via early retirement completely separate from its store closings, and HHGregg is shedding 1,500 jobs as stores close. And thousands more are being lost across traditional retail in stores, supply chain positions and headquarters facilities.

Traditional retail employs about 16.5 million Americans – nearly 10% of the entire workforce. 6.2 million are in the prime product lines targeted by e-commerce (GAFO – General, Apparel, Furniture and Other.) The Amazon Effect will continue to eliminate these positions. Over the next five years it is not unlikely that the decline of brick-and-mortar will cause 16% of GAFO jobs to disappear, which is almost 1 million jobs. Simultaneously this could easily cause 10% of the non-GAFO jobs (10.3 million) to disappear – which is another 1 million. This likely scenario would cause the loss of 2 million jobs in just five years, which is the entirety of all lost manufacturing jobs to China. The Trump administration has more employment concerns to face than just the return of manufacturing.

The Amazon Effect is changing grocery shopping, without even being a major competitor in that sector. Because Wal-Mart has lost so much general merchandise sales to e-commerce, the company has amped up grocery sales – which are now 56% of total revenue. To continue growing groceries Wal-Mart is undertaking a massive price war pitting itself against the long-running low cost grocer Aldi. This is creating even more intense profit pressure on Wal-Mart, which last year saw gross margins drop by eight points, as net income fell 18%. Such intense price competition is creating the need for even more cost cutting among all grocers – which means investors beware – and we can expect even more job cutting as the spiral downward continues.

Consumer Goods manufacturers, and their suppliers, will be stressed.

Of course this pushes the Amazon Effect onto consumer goods companies that supply grocery retailers. Wal-Mart has held meetings with P&G, Unilever, Conagra, Coca-Cola and other big name companies demanding across-the-board 15% price reductions at wholesale. And Wal-Mart expects these suppliers to help Wal-Mart beat its head-to-head competitors on price 8o% of the time. This will cause consumer goods manufacturers to cut their own costs, including jobs, as well as pressure their raw material suppliers to further reduce their costs – leading to an ongoing spiral of cost cutting, job eliminations and additional pressures for change.

The internet gave us e-commerce, and that birthed Amazon.com. Few predicted the enormous implications this would have on retail, and society. Every single American is affected by the Amazon Effect, which is now inescapable. The only remaining question is whether your business, your government leaders and you are planning for this and preparing for the inevitable changes which will continue coming?

by Adam Hartung | Feb 22, 2017 | Immigration, Leadership, Politics

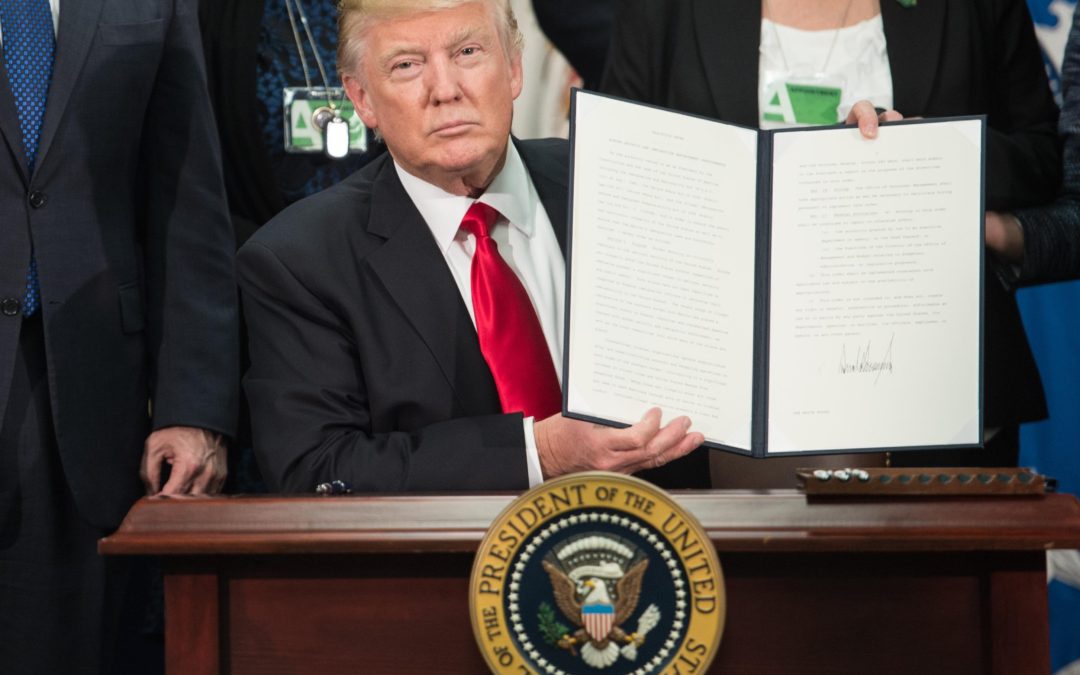

(Photo by Olivier Douliery-Pool/Getty Images)

There is a lot of excitement about President Donald Trump’s planned new executive order on immigration. Before the order is even public, the press has been grilling White House Press Secretary Sean Spicer about its contents. People are preparing to object before the document is even read.

Given that we know the order deals only with immigrants from seven countries, and that people from those countries do not constitute anywhere near a meaningful minority of immigrants (or tourists), one could make a case that in and of itself the executive order should not receive anywhere near this much attention.

But simultaneously, President Trump’s secretary of state and secretary of homeland security are visiting Mexico on Thursday — which is creating its own a firestorm of media coverage. The Mexican government leadership has already come out swinging, before the meeting, saying that the Trump administration policies are unacceptable. Not only is the wall construction unacceptable, but plans to deport illegal immigrants to Mexico — including illegal immigrants that are not Mexican — will not be tolerated. They want to know why should Mexico be forced to take Guatemalans, Hondurans and other non-Mexicans?

All of this controversy is being driven by the U.S. leadership, the president and his cabinet, failing to offer a clear policy on immigration. These executive orders, impending demands and vitriolic statements from the administration are like rifle shots aimed at something. But because nobody has a clue what the administrations real immigration policy is, it is impossible to understand the context from which these shots are fired. Nobody really knows what these shots are aimed at achieving.

So everyone, including the media, is left guessing, “what is the target of these actions? What is the overall goal? What is the administration’s immigration policy into which these actions fit?”

The administration says these actions are driven by “national security.” But it is impossible to understand that claim lacking any context. How are these specific actions supposed to improve national security, when every day people come to the U.S. from Europe and Asia with Muslim backgrounds and training? People cross the Canadian border daily who started in another country, yet they are not seen as the same threats as those who cross the southern border — why not?

Thus, each rifle shot looks an awful lot like an attack against the narrow interest being targeted — specifically middle eastern Muslims and Mexicans. And a lot of people are left scratching their heads as to why these folks are being attacked, other than they are simply easy targets for a part of the U.S. population that is horribly xenophobic.

Everyone — and I literally mean everyone — knows that America is a nation of immigrants. Last Labor Day I wrote about the benefits America has enjoyed by opening its doors to immigration. Recently Ryan McCready of Venngage put together a detailed infographic describing how over half of America’s billion dollar start-ups were founded by immigrants, how 33,000 permanent jobs were created by immigrants, how 76% of patents from top universities were filed by immigrants, and how 100% of America’s 2016 Nobel Prize recipients were immigrants. Nobody really doubts that immigrants have been good for America.

But, everyone also knows all immigrants are not the target of the Trump administration rhetoric, travel restrictions or executive orders. On January 28, in an editor’s pick column, I detailed how the border wall does not even address the problem of illegal immigrants that might be stealing jobs or committing crimes. If it was easy for me to produce the data that it is not illegal Mexican immigrants stealing jobs or creating crime, no doubt the people atop our government have even better data.

Another, possibly more obscure, example of an unaddressed immigration issue was brought to my attention in a recent BBC column (thanks to my cousin Susan Froebel from Austin, TX). Developers are planning for a large migration of retired Chinese to the U.S. These Chinese will enter America with no income, and no job prospects. They are escaping China, where the aged population is growing so fast there is great concern the workforce cannot care for them. They will increase the aged population in American, putting greater strains on all social services — housing, food, medicine. This will increase demands on the remaining American workers, as the U.S.’s own baby boomer generation retires, creating the worst imbalance of non-workers to workers in American history.

If there is any demographic you do not want immigrating to the U.S. it is a bunch of retired people. As I pointed out in my September 16 column, as any country’s population ages it creates a demand for more young immigrants to create economic productivity, growth and the resources to take care of the non-productive retirees. Rather than retirees, what America needs are young, productive immigrants who create and fill jobs — growing the economic base and paying taxes to support the rising retiree class.

But, I’d bet almost nobody who reads this column even knows about the impending explosion of retired Chinese planning to permanently enter the U.S. Even though the economic impact could be disastrous — far, far worse than a few million undocumented workers from Mexico or the middle east. Instead the focus is on two very targeted groups — Muslims and Mexicans.

The Elephant In The Room

Unfortunately, we all remember the infamous voter who attended a John McCain rally in 2007 and said that then-candidate Barack Obama was a Muslim born in Africa. In that moment that woman put forward the fears of so many Americans — that you cannot trust a dark skinned person. You cannot trust anyone who is not Christian. You cannot trust anyone who is not born within the U.S. Everyone else is someone to fear.

Lacking a well drafted, and at least somewhat comprehensive immigration policy, the immediate actions of the U.S. president sound a lot like, Stop the Muslims. Stop the Mexicans. After all, everyone knows they cannot be trusted. They are bad hombres.

Does the U.S. need more border protection? Does the U.S. need to crack down on illegal immigrants?Does the U.S. need to limit immigration? Perhaps yes — perhaps no. And if so, by how much? Right now nobody knows what the Trump administration immigration policy is. All the administration has put forward are rifle shots that appear to be pointed at the easiest targets of hatred in America today — Muslims and Mexicans. Whether these groups deserve to be targeted, or not.

Good leaders develop their vision first. The leadership team puts together the vision, mission and goals for the organization. Then this is developed into a strategy which guides investment and decision-making. The policy platform provides the context so the leaders, and all constituents, can identify the goals of the organization and the planned route to achieve those goals. After that is in place independent actions (decisions) can be evaluated as to their fit with the vision, mission and overall strategy.

As business leaders, President Trump and Secretary Tillerson (former ExxonMobile CEO) should know these first principles of leadership. Yet, they have failed to provide this vision. They have failed to describe their strategy to accomplish their mission. They have failed to tie their words and actions to a plan for achieving their goals (goals which are also still quite vague — such as “a safer America” or “a greater America”). So their actions are being interpreted by their constituents from each constituent’s perspective.

No wonder everyone has an opinion about what’s happening — and no wonder so many people are full of angst. There is a reason leaders take time in their early days to put develop their platform, and discuss it with constituents. Successful leaders make sure the people they depend upon know their vision, goals and strategy (in this case not only voters but Senators, members of Congress, the judiciary, law enforcement, military and regulators). Only after this do they take action — action clearly aligned with their vision, supported in the strategy and directed at achieving their goals.

For now, lacking the proper context, most Americans are interpreting short-term immigration actions as attacks on Muslims and Mexicans. Those who like these actions do so thinking it is proper, and those who dislike these actions think it is unfair targeting. But people will continue to make their own interpretations until a comprehensive policy is offered that explains a different context. As long as that policy is unclear, these poorly explained actions are examples of bad leadership.

by Adam Hartung | Feb 15, 2017 | Marketing, Mobile, Retail, Web/Tech

(Photo by Andrew Burton/Getty Images)

Apple’s stock is on a tear. After languishing for well over a year, it is back to record high levels. Once again Apple is the most valuable publicly traded company in America, with a market capitalization exceeding $700 billion. And pretty overwhelmingly, analysts are calling for Apple’s value to continue rising.

But today’s Apple, and the Apple emerging for the future, is absolutely not the Apple which brought investors to this dance. That Apple was all about innovation. That Apple identified big trends – specifically mobile – then created products that turned the trend into enormous markets. The old Apple knew that to create those new markets required an intense devotion to product development, bringing new capabilities to products that opened entirely new markets where needs were previously unmet, and making customers into devotees with really good quality and customer service.

That Apple was built by Steve Jobs. Today’s Apple has been remade by Tim Cook, and it is an entirely different company.

Today’s Apple – the one today’s analysts love – is all about making and selling more iPhones. And treating those iPhone users as a “loyal base” to which they can sell all kinds of apps/services. Today’s Apple is about using the company’s storied position, and brand leadership, to milk more money out of customers that own their devices, and expanding into adjacent markets where the installed base can continue growing.

UBS likes Apple because they think the services business is undervalued. After noting that it today would stand alone as a Fortune 100 company, they expect those services to double in four years. Bernstein notes services today represents 11% of revenue, and should grow at 22% per year. Meanwhile they expect the installed base of iPhones to expand by 27% – largely due to offshore sales – adding further to services growth.

Analysts further like Apple’s likely expansion into India – a previously almost untapped market. CEO Cook has led negotiations to have Foxxcon and Wistron, the current Chinese-based manufacturers, open plants in India for domestic production of iPhones. This expansion into a new geographic market is anticipated to produce tremendous iPhone sales growth. Do you remember when, just before filing for bankruptcy, Krispy Kreme was going to keep up its valuation by expanding into China?

Of course, with so many millions of devices, it is expected that the apps and services to be deployed on those devices will continue growing. Likely exponentially. The iOS developer community has long been one of Apple’s great strengths. Developers like how quickly they can deploy new apps and services to the market via Apple’s sales infrastructure. And with companies the size of IBM dedicated to building enterprise apps for iOS the story heard over and again is about expanding the installed base, then selling the add-ons.

Gee, sounds a lot like the old “razors lead to razor blade sales” strategy – business innovation circa 1966.

Overall, doesn’t this sound a lot like Microsoft? Bill Gates founded a company that revolutionized computing with low-cost software on low-cast hardware that did just about anything you would want. Windows made life easy. Microsoft gave users office automation, databases and all the basic work tools. And when the internet came along Microsoft connected everyone with Internet Explorer – for free! Microsoft created a platform with Windows upon which hordes of developers could build special applications for dedicated markets.

Once this market was created, and pretty much monopolized by Microsoft CEO Gates turned the reigns over to CEO Steve Ballmer. And Mr. Ballmer maximized these advantages. He invested constantly in developing updates to Windows and Office which would continue to insure Microsoft’s market share against emerging competitors like Unix and Linux. The money was so good that over a decade money was poured into gaming, even though that business lost more money than it made in revenue – but who cared? There were occasional investments in products like tablets, hand-helds and phones, but these were merely attractions around the main show. These products came and went and, again, nobody really cared.

Ballmer optimized the gains from Microsoft’s installed base. And a lot – a lot – of money was made doing this. nvestors appreciated the years of ongoing profits, dividends – and even occasional special dividends – as the money poured in. Microsoft was unstoppable in personal computing. The only thing that slowed Microsoft down was the market shift to mobile, which caused the PC market to collapse as unit sales have declined for six straight years (PC sales in 2016 barely managed levels of 2006). But, for a goodly while, it was a great ride!

Today all one hears about at Apple is growing the installed base. Maximizing sales of iPhones. And then selling everyone services. Oh yeah, the Apple Watch came out. Sort of flopped. Nobody really seemed to care much. Not nearly as much as they cared about 2 quarters of sales declines in iPhones. And whatever happened to AppleTV? ApplePay? iBeacons? Beats? Weren’t those supposed to be breakthrough innovations to create new markets? Oh well, nobody seems to much care about those things any longer. Attractions around the main event – iPhones!

So now analysts today aren’t put in the mode of evaluating breakthrough innovations and trying to guess the size of brand new, never before measured markets. That was hard. Now they can be far more predictable forecasting smartphone sales and services revenue, with simulations up and down. And that means they can focus on cash flow. After all, Apple makes more cash than it makes profit! Apple has a $246 billion cash hoard. Most people think Berkshire Hathaway, led by famed investor Warren Buffett, spent $6.6 billion on Apple stock in 2016 because Berkshire sees Apple as a cash generation machine – sort of like a railroad! And if those meetings between CEO Cook and President Trump can yield a tax change allowing repatriation at a low rate then all that cash could lead to a big one time dividend!

And, most likely, the stock will go up. Most likely, a lot. Because for at least a while Apple’s iPhone business is going to be pretty good. And the services business is going to grow. It will be a lot like Microsoft – at least until mobile changed the business. Or, maybe like Xerox giving away copiers to obtain toner sales – until desktop publishing and email cratered the need for copiers and large printers. Or, going all the way back into the 1950s and 60s, when Multigraphics and AB Dick practically gave away small printers to get the ink and plate sales – until xerography crushed that business. Of course you couldn’t go wrong investing in Sears for years, because they had the store locations, they had the brands (Kenmore, Craftsman, et.al.,) they had the credit card services – until Wal-Mart and Amazon changed that game.

You see, that’s the problem with all of these sort of “milk the base” businesses. As the focus shifts to grow the base and add-on sales the company loses sight of customer needs. Innovation declines, then evaporates as everything is poured into maximizing returns from the “core” business. Optimization leads to a focus on costs, and price reductions. Arrogance, based on market leadership, emerges and customer service starts to wane. Quality falters, but is not considered as important because sales are so large.

These changes take time, and the business looks really good as profits and cash flow continue, so it is easy to overlook these cultural and organizational changes, and their potential negative impact. Many applaud cost reductions – remember the glee with which analysts bragged about the cost savings when Dell moved its customer service to India some 20 years ago?

Today we’re hearing more stories about long-term Apple customers who aren’t as happy as they once were.

Genius bar experiences aren’t always great. In a telling AdAge column one long-time Apple user discusses how he had two iPhones fail, and Apple could not replace them leaving the customer with no phone for two weeks – demonstrating a lack of planning for product failures and a lack of concern for customer service. And the same issues were apparent when his corporate Macbook Pro failed. This same corporate customer bemoans design changes that have led to incompatible dongles and jacks, making interoperability problematic even within the Apple line.

Meanwhile, over the last four years Apple has spent lavishly on a new corporate headquarters befitting the country’s most valuable publicly traded company. And Apple leaders have been obsessive about making sure this building is built right! Which sounds well and good, except this was a company that once put customers – and unearthing their hidden needs, wants and wishes – first. Now, a lot of attention is looking inward. Looking at how they are spending all that money from milking the installed base. Putting some of the best managers on building the building – rather than creating new markets.

Who was that retailer that was so successful that it built what was, at the time, the world’s tallest building? Oh yeah, that was Sears.

Markets always shift. Change happens. Today it happens faster than ever in history. And nowhere does change happen faster than in technology and consumer electronics. CEO Cook is leading like CEO Ballmer. He is maximizing the value, and profitability, of the Apple’s core product – the iPhone. And analysts love it. It would be wise to disavow yourself of any thoughts that Apple will be the innovative market creating Jobs/Ives organization it once was.

How long will this be a winning strategy? Your answer to that should determine how long you would like to be an Apple investor. Because some day something new will come along.

by Adam Hartung | Feb 7, 2017 | Investing, Trends

The vast majority of individual investors have no idea how to pick stocks. So they often let someone else invest for them, and pay a hefty fee of anywhere from 1% to 5% of their assets annually. Or they buy some sort of fund or portfolio index, where they pay the fund manager usually more than 1% of assets for managing the fund. In the worst case, they pay the financial advisor their fee, and then the advisor buys a fund for the investor – which has that investor paying anywhere from 2% to 8% or even 10% of assets annually for investment advice.

Yet, we know that few asset managers can beat “the market,” whether measured by the DJIA (Dow Jones Industrial Average) or the S&P 500. A study in Europe showed no active manager beat their benchmark over 10 years, and in the U.S. 80% to 90% of fund managers failed to do as well as their benchmarks. And there are studies showing that even if a manager beats their index, after accounting for management fees and costs the investors almost never beat the market.

Any individual could buy the market index by simply opening an on-line account at any discount brokerage, for a very small cost, and buying the exchange traded fund (ETF) for the Dow (DIA – often called “Diamonds”) or the S&P (SPDR – often called “Spiders”). Thus, individual investors can do as well as the “market” at very, very low cost. Most academics will tell investors to not try and beat the market, because the market is wildly inefficient and investors are always without full knowledge of the company, and thus buy these indices.

But most investors are lured by the notion of “beating the market” so they pay the high fees in order to – hopefully – have someone do a better job of investing. And they end up disappointed.

Investors can “beat the market,” but it requires a different approach to investing than fund managers use. And it is far more suited to individuals, with long-term horizons – and it avoids paying those outrageous financial services fees. To be a long-term high-return investor individuals simply need to invest in trends.

247wallst.com published an article stating the editors had seen a report published by Jefferies, sent to them by Bloomberg, which claimed that 20% of all the gains in the total stock market since 1924 (some 93 years) were created by a mere 14 stocks. This sort of blows up all academic theories about investing in portfolios, as it drives home that most market returns are driven by a small collection of companies. Individuals would be better off if they invested in just a few stocks, rather than all stocks. But this means you have to know which stocks to own.

You would think this might be hard, until you look at the list of 14. There is a striking pattern. All were simply the biggest, most powerful companies leading an important, large trend. So if you identified the trend, and invested in the largest company creating that trend, you would do really well. And because these are large companies, investors aren’t carrying the risk of small companies that could be competitively destroyed by larger players. Interestingly, identifying these trends and the large players really isn’t that hard. Nor is it hard to recognize when the trend is ending, and it is time to sell.

We can understand this by looking at the list of 14 not by how much market gain they created, but rather historically when the majority of those gains occurred.

People have enjoyed smoking tobacco since at least the 1500s. Long before anyone knew about the chemical affects and shortened lifespan people simply enjoyed the practice of smoking and the impact nicotine had on them. As tobacco spread from France to England, eventually it moved to the U.S. and was the first ever cash crop – grown in America for sale in Europe. For literally hundreds of years the trend toward tobacco consumption grew. So, it is easy to understand why investing in Phillip Morris, which was renamed Altria, was a good move. As long as people kept buying more cigarettes investing in the largest cigarette company was a good way to increase your returns.

For hundreds of years people used whale oil and similar animal products for candles and lanterns. Wood and coal were used for cooking. But then in 1859 oil was successfully found, and it changed the world. Oil was far cheaper to produce than animal or vegetable oils and burned more consistently at a higher temperature than those products, wood or coal. And that unleashed a trend toward hydrocarbon production leading to the birth of countless new products. It would not have been hard to see that this trend was going to be very valuable. Thus two other names on the list pop up, Exxon and Chevron. These companies are successors of the original Standard Oil founded by John Rockefeller – which created tremendous returns for investors for many years as oil consumption, and production, grew.

Hydrocarbons were a tremendous contributor to the industrial revolution, allowing manufacturers to use engines in new products, and to improve their manufacturing. One of the earliest, and soon biggest, manufacturers was General Electric, another big value producer on the list of 14. And one of the biggest industrial revolution gains was the automobile, where General Motors became by far the largest producer. Investors who put money into the industrial revolution and the trend toward making things – especially cars – came out very well by buying shares in these two companies.

As the industrial revolution grew the middle class emerged, enjoying a vast improvement in quality of life. This led to the trend of consumerism, as it was possible to make things much cheaper and distribute them wider. Three of the biggest companies that promoted this consumer trend were Johnson & Johnson, Proctor & Gamble and Coca-Cola. All were in different product markets, but all were very big leaders in the growth of consumer products for a 1900s world (especially post-WWII) where people had more money – and the desire to buy things. And all three did very well for their investors.

Soon a new trend emerged with the capability of electronics. First came the advent of instant, modern communications as the telephone emerged. Regardless the cost, there was high value in being able to communicate with someone “now” even if they were in a distant location. Investors in Alexander Bell’s AT&T did quite well as phones made their way across America and around the world.

Soon thereafter mechanical adding machines were greatly improved by using electronics – initially relays – to make tabulations and computations. IBM was an early developer of these machines for commercial use, and very quickly came to dominate the market for computers. It was not long before every company needed a computer, or at least access to use one, in order to compete. Investors in IBM were well rewarded for spotting this trend.

As the market for consumer goods exploded Sam Walton recognized the inefficiency of retail product distribution. He discovered that by owning more stores he could negotiate better with consumer goods manufacturers, purchase products more cheaply and sell them more cheaply. He created the trend toward mass retailing driven by efficiency, and he rapidly demonstrated the ability to drive competitors completely out of many retail markets. Investors who identified this trend toward low-cost retailing of a wide product array made considerable gains by purchasing Wal-Mart shares.

As computers became smaller the market expanded, leading to the development of ever smaller computers. Microsoft created software allowing multiple manufacturers to build machines with interoperability, allowing it to take a dominant position in the trend to computers so small every single person could have one – and indeed eventually felt they could not live without one. Microsoft investors made huge gains as the company practically monopolized this trend and created the personal compute marketplace.

It was Apple that first recognized the trend toward mobility being created by ever faster connection speeds. Mobility would allow for radical changes in how many product markets behaved, and investors who saw this mobility trend were amply rewarded for investing in Apple – the company that became synonymous with internet-enabled products.

And as computing mobility improved it created a trend toward buying at home rather than going to a store. Mail order had almost entirely disappeared, due to lack of timely product fulfillment. But with the internet as the interface, coupled with modern, highly efficient transportation services, Amazon was able to give a rebirth to shopping from home and the e-commerce trend exploded. Investors that recognized Amazon’s vastly lower cost retail model, coupled with the infinite prospects for product variety, have been rewarded for investing in the large on-line retailer.

These 14 companies created 20% of all stock market gains across nearly a century. And each was the dominant competitor in a major trend. Several are no longer on the trend, and even a couple have filed bankruptcy (like AT&T and GM), thus it is easy to recognize why some have done far less well the last decade. The world changed and their business model which once produced excellent returns no longer does. But savvy investors should recognize when a trend has run its course, and drop that company in favor of investing in the leader of a major, new trend.

All investors should be long-term investors. Trying to be a market timer, and a trader, is a fool’s errand. To make high investment returns requires taking a long-term (multi-year) view – not monthly or quarterly. Therefore it is important that when investing in trends they be big trends. Trends that will have a large impact on every business – every person. Trends that can generate tremendous returns for many years.

Not everyone can be a stock picker. Therefore, most investors should probably have a goodly chunk of their money in an ETF. That can be done easily enough as described above. But, if you want to increase your returns to beat the market the key is to invest in companies that are large, and the leaders in a major trend.

What are the big trends today? There is no doubt “social” is a huge trend. How every business and person interacts is changing as the use of social tools increases. This is a global phenomenon, and it is a trend with many years left to extend its impact. Investing in the market leader – Facebook – shows good likelihood of obtaining the kind of returns created by the 14 companies discussed above.

What other trends can you identify that have years yet to go? If you can spot them, and invest in a dominant, large leader then you just may outperform nearly every active fund manager trying to get you to pay their fees.

by Adam Hartung | Jan 28, 2017 | Immigration, Leadership, Politics, Trends

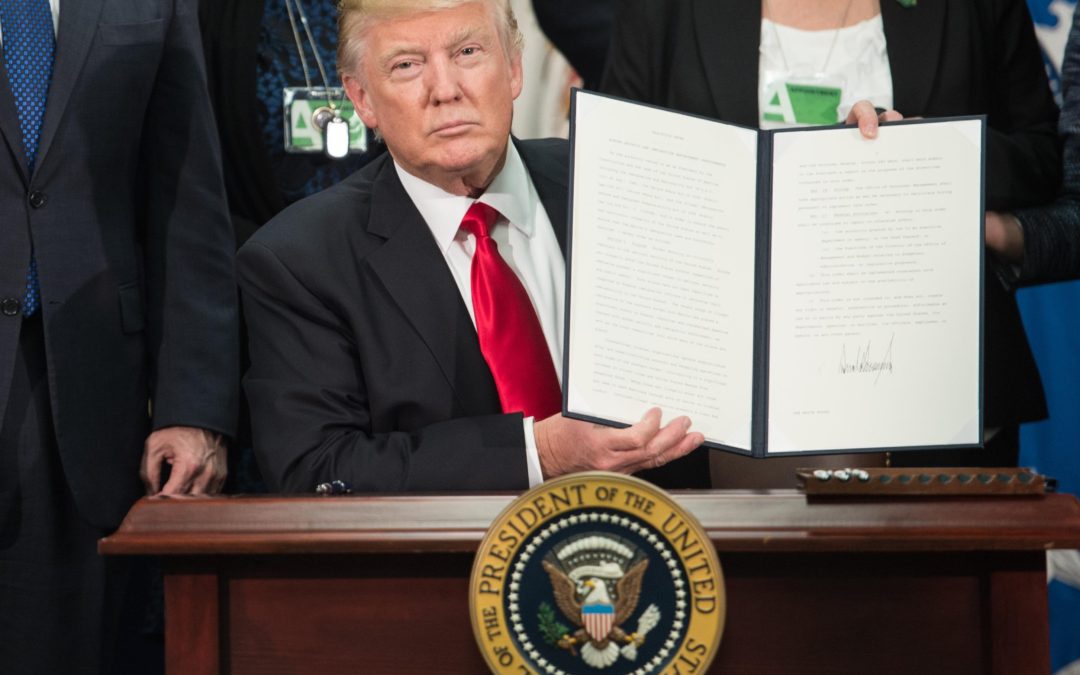

(Photo: NICHOLAS KAMM/AFP/Getty Images)

“Get the assumptions wrong and nothing else matters” – Peter F. Drucker

President Donald Trump made it very clear last week that his administration intends to build a border wall between the U.S. and Mexico. And he intends to make Mexico pay for it. He is so adamant he is willing to risk U.S./Mexican relations, canceling a meeting with the Mexican president.

Unfortunately, this tempest is all because of a really bad idea. The wall is a bad idea because the assumptions behind this project are entirely false. Like far too many executives, President Trump is building a plan based on bad assumptions rather than obtaining the facts – even if they belie his assumptions – and developing a good solution. Making decisions, and investing, on bad assumptions is simply bad leadership.

The stated claim is Mexico is sending illegal immigrants across the border in droves. These illegal immigrants are Mexican ne’er do wells who are coming to America to live off government subsidies and/or commit criminal activity. The others are coming to steal higher paying jobs from American workers. America will create a h

Unfortunately, almost everything in that line of logic is untrue. And thus the purported conclusion will not happen.

1. Although it cannot be proven, analysts believe the majority (possibly vast majority) of illegal immigrants enter America by air. There are two kinds of illegal immigration. President Trump’s rhetoric focuses on “entries without inspection.” But most illegal immigrants actually arrive in America with a visa – and then simply don’t leave. These are called “overstays.” They come from Mexico, India, Canada, Europe, Asia, South America, Africa – all over the world. If you want to identify and reduce illegal immigration, you need to focus on identifying likely overstays and making sure they return. The wall does not address this.

3. More non-Mexicans than Mexicans were apprehended at the U.S. border – and the the number of Mexicans has been declining. From 1.6 million in 2000, by 2014 the number dwindled to 229,000 (a decline of 85%). If you want to stop illegal border immigrants into the U.S., the best (and least costly) policy would be to cooperate with Mexico to capture these immigrants as they flee Central America and find a solution for either housing them in Mexico or returning them to their country of origin. It is ridiculous to expect Mexico to pay for a wall when it is not Mexico’s citizens creating the purported illegal immigration problem on the border.

4. In 2015 over 43,000 Cubans illegally immigrated to the U.S. – about 20% as many as from Mexico. The cost of a wall is rather dramatically high given the weighted number of illegal immigrants from other countries.

5. The number of illegal immigrants living in the U.S. is actually declining. There are more Mexicans returning to live in Mexico than are illegally entering the U.S. Between 2009 and 2014 over 1 million illegal Mexican immigrants willingly returned to Mexico where working conditions had improved and they could be with family. In other words, there were more American jobs created by Mexicans returning to Mexico than “stolen” by new illegal immigrants entering the country. If the administration would like to stop illegal immigration the best way is to help Mexico create more high-paying jobs (say with a trade deal like NAFTA) so they don’t come to America, and those in America simply choose to go to Mexico.

6. Illegal immigrants are not “stealing” more jobs every year. Since 2006, the number of illegal immigrants working in the U.S. has stabilized at about 8 million. All the new job growth over the last decade has gone to legitimate American workers or legal immigrants working with proper papers. Illegal immigration is not the reason some Americans do not have jobs, and blaming illegal immigrants is a ruse for people who simply don’t want to work – or refuse to upgrade their skills to make themselves employable.

7. Illegal immigrants in the U.S. is not a rising group – in fact most illegal immigrants have been in the U.S. for over 10 years. In 2014, over 66% of all illegal immigrants had been in the U.S. for 10 years or more. Only 14% have been in the U.S. for 5 years or less. We don’t have a problem needing to stop new illegal immigrants (the ostensible reason for a wall). Rather, we have a need to reform immigration so all these long-term immigrants already in the workforce can be normalized and make sure they pay the necessary taxes.

8. The states where illegal immigration is growing are not on the Mexican border. The states with rising illegal immigration are Washington, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Virginia, Massachusetts and Louisiana. Texas, New Mexico and Arizona have seen no significant, measurable increase in illegal immigrants. And California, Nevada, Illinois, Alabama, Georgia and South Carolina have seen their illegal immigrant population decline. A border wall does not address the growth of illegal immigrants, as to the extent illegal immigrants are working in the U.S. they are clearly not in the border states.

Good leaders get all the facts. They sift through the facts to determine problems, and develop solutions which address the problem.

Bad leaders jump to conclusions. They base their actions on outdated assumptions. They invest in the wrong places because they think they know everything, rather than making sure they know the situation as it really exists.

America’s “flood of illegal immigrants” problem is wildly overblown. Most illegal immigrants are people from advanced countries, often with an education, who overstay their visa limits. But few Americans seem to think they are a problem.

Most border crossing illegal immigrants today are minors from Central America simply trying to stay alive. They aren’t Mexican criminals, stealing jobs, or creating a crime spree. They are mostly starving.

President Trump has “whipped up” a lot of popular anxiety with his claims about illegal Mexican immigrants and the need to build a border wall. Interestingly, the state with the longest Mexican border is Texas – and of its 38 congressional members (36 in Congress, 2 in the Senate and 25 Republican) not one (not one) supports building the wall. The district with the longest border (800 miles) is represented by Republican Will Hurd, who said “building a wall is the most expensive and least effective way to secure the border.”

Good leaders do not make decisions on bad assumptions. Good leaders don’t rely on “alternative facts.” Good leaders carefully study, dig deeply to find facts, analyze those facts to determine if there is a problem – and then understand that problem deeply. Only after all that do they invest resources on plans that address problems most effectively for the greatest return.

by Adam Hartung | Jan 24, 2017 | Leadership, Politics

(Photo by Shawn Thew-Pool/Getty Images)

Professor John Kotter (Konosuke Matsushita Professor of Leadership HBS) penned Power and Influence (1985, Free Press) after teaching his course of the same name at the Harvard Business School. The one thing he found clear, as did his students (of which I was one), was that a person can be powerful and have influence, but that does not make them a leader. Leaders understand how to create and use both power and influence. But merely having access to either, or both, does not make a person a leader.

One of my mentors, Colonel Carl Bernard, famed leader of U.S. Special Forces in Laos and Vietnam during the 1960s, met an executive at DuPont in the mid-1980s who had been given a large organization but was struggling. Col. Bernard was asked to review this fellow and offer his leadership insights so this fellow’s peers could help him be a better corporate leader. After a few meetings with this exec, alone and in groups, Col. Bernard concluded, “DuPont can give him resources, and access to the CEO, but that man could not lead a Boy Scout troop. Best they close the business now before he causes too much trouble. There’s nothing I can do for him.” Two years later, and tremendous turmoil later, DuPont did close that business, fired him and wrote off everything the company had invested.

Last Friday, Donald Trump was sworn in as president of the United States. He now has the most powerful job in the free world and unparalleled influence. But, he’s not yet proven himself a leader. His accomplishments to date have all been executive orders – issued unilaterally. To achieve the title “leader,” he has to prove people will follow him.

President Trump did not win the popular vote, and he assumes his new job with the lowest approval rating of any first-term president ever elected. Numbers alone do not imply that the country is ready to call him its leader.

Historically, a president has had to screw up in office to have such low popularity. But on Saturday millions of demonstrators took to the streets of Washington, Los Angeles, Chicago, Minneapolis and other cities to protest a president who had yet to do anything in his new role. Far more demonstrated than attended the inauguration, which had about half the attendees as Barack Obama’s first inauguration. It took Lyndon Johnson years to create the animosity which lead to demonstrators chanting, “Hey, hey LBJ, how many kids did you kill today?” (referencing his escalation of the Vietnam War).

Business school thought leaders, and business executives, have been studying leadership for at least six decades, and they have discovered there are consistencies in how to encourage followership. Roger Ferguson, CEO of TIAA-CREF,

said leadership is about inspiring people. He teaches that this is done by

• demonstrating expertise – which Trump has yet to do as a politician,

• making yourself appealing – which Trump has missed by deriding those who speak out against him,

• showing empathy for others – a trait so far missing in Trump’s tweets, or comments about detractors

• and showing the fortitude of being the calm in the storm – the opposite of Trump, who’s fiery rhetoric creates more storms than it calms.

In 2013, fellow Forbes contributor Mike Myatt offered his insights into how one should lead those who don’t want to follow, tips that should be very interesting to the unpopular President Trump:

• Be consistent. This seems the antithesis of Trump, who favors inconsistency and campaigned that as President he intended to be inconsistent.

• Focus on what’s important. Reading Trump’s tweets, it is clear he struggles to separate the important from the meaningless

• Make respect a priority. Should we talk about Trump’s references to women? Or his comments about war heroes like John McCain?

• Know what’s in it for the other guy. Trump likes to brag about taking advantage of others in his business dealings, and showing blatant disregard for the concerns of others. Recommending African-Americans vote for him because “what have you got to lose” does not demonstrate knowledge of that constituency’s needs.

• Demonstrate clarity of purpose. Firstly, what does it mean to “make America great again?” It would be nice to know what that slogan even means. Second, if Trump is the President for “those of you left behind,” as he referenced in his inauguration speech, can he tell us who is in that group? Am I included? Are you? How do you know who’s in this group he now represents? And who’s not?

Americans frequently confuse position with leadership. Many CEOs are treated laudably, even after they have destroyed shareholder value, destroyed thousands of jobs, stripped suppliers of money and resources, doomed local economies with shuttered facilities and left their positions with millions of dollars despite a terrible performance. These CEOs demonstrated they had power and influence. But many are despised by their former employees, investors, bankers, suppliers and community connections. They did not demonstrate they were leaders.

Despite his great wealth, which has bought him substantial power and influence, Americans have yet to see if President Trump can lead. He has never been a commissioned or non-commissioned officer in a military organization. He has never led a substantial corporation with large employment. He has never led a substantial non-profit or religious organization. Contrarily, he has largely been the head of hundreds of small businesses (by employee standards) many of which he has closed or bankrupted, often leaving people unemployed, his investors losing money and communities (such as Atlantic City) worse off from his real estate dealings.

I prefer to write about corporate leaders and market leaders. But for a while now, almost all the news has been about Mr. Trump. Now President Trump, who has not previously led even a Boy Scout troop. One wonders of Col. Bernard would think he could.

“The greatest leader is not necessarily the one who does the greatest things. He is the one that gets the people to do the greatest things” – Ronald Reagan

by Adam Hartung | Jan 16, 2017 | Economy, Politics, Trends

Trend analysis is the most critical part of planning.

Some trends are hard to spot, because people think they are just a fad. Many folks think electric cars fit that category.

Other trends are hard to accept because they imply a big shift in how we live or work – or how we run our business. Scores of IT people who have written me over the years saying mobile devices on common networks (telecom to AWS) will never replace PCs connected to server farms. The implications of this trend are severely negative related to demand for their skills, so they ignore it.

But every plan should be built on trends, because these forecasts are critical for decision-making. It’s the future that matters, not the past. Too often plans are built on history, when trends clearly indicate that things are going to change, and old assumptions are outdated.

Demographic trends are easy to forecast, and important.

While some trends are hard to forecast, some trends are really easy to spot and forecast. And the easiest trend to understand is demographics. If you don’t use any other trends in your planning, you should have demographic trends at the core of your assumptions.

Take for example the movement of people across the United States. Ever since the wagon train people have been moving west. And, like my friend Buckley Brinkman (executive director and CEO of the Wisconsin Center for Manufacturing and Productivity) likes to say, “ever since the invention of air conditioning people have been moving south.” Yet, I’m startled how few organizations plan for this shift and adjust their strategies and tactics to be more successful.

From July 1, 2015 to July 1, 2016 the seven fastest growing states were western. And of 50 states, only eight lost population.

Growth is sublime, decline is disastrous.

Bruce Henderson, founder of the Boston Consulting Group, used to say that if you want to hunt or farm you’re far better off in the Amazon than you are in the Arctic. Basically, where there are resources, and lots of growth, it’s a lot easier to succeed.

For business, this means that if you want to grow your business – whether you’re installing HVAC systems or building a state-of-the-art battery manufacturing plant – you’ll find it relatively easier in faster growing states. It doesn’t mean there is no competition, but it does mean that growth makes it easier for competitors to succeed.

Contrastingly, there were eight states that lost population in this same 12 months.

This means that competition is intensifying in these states. As people move out there are fewer customers to buy what each business sells, so these companies have to fight harder, and price lower, to grow – or even maintain. As the population declines taxes have to go up because there are fewer taxpayers to cover government costs. These states become less desirable places for business.

The businesses in Illinois, for example, are in the middle of a bare-knuckle brawl over the state budget that has gone on for two years. The Governor and the legislature cannot agree on how to manage costs, or revenues. Bond ratings have been slashed as costs to borrow have gone up. Several services have been shut down, and student costs at universities have gone up while programs have been gutted or discontinued.

Governor Rauner (R – IL) has repeatedly said he wants Illinois to be more like Indiana, its neighbor to the east. Perversely people apparently are listening, because Illinois is shrinking, while Indiana grew a healthy 0.31%. For residents remaining in Illinois this worsens a host of maladies:

• the state’s jobs situation struggles as the number of paying jobs declines, making it harder to recruit new talent, or even keep its own university graduates;

• Illinois’ pension problems worsen, as there are fewer people paying into the pension funds while those drawing out funds keep increasing;

• Illinois is unable to fund schools properly, especially Chicago, due to less income – forcing up property taxes;

• taxes keep rising due to fewer people and businesses (when adding property taxes, sales taxes and income taxes Illinois is now the highest tax state in the country);

• new highways are being built with federal funds, but other infrastructure is in trouble, as city, county and state roads are pothole ridden. Trains and subways become outdated and fall into disrepair. And one-time budget Hail Mary’s, like Chicago selling its parking structures and meters in order to balance the budget for one year, strip citizens of future revenues while they watch parking (and other) service costs skyrocket;

• and Chicago has suffered the lowest real estate recovery rate of the top 30 major U.S. cities –not even returning to prices in 2008.

Growth solves a multitude of sins.

Just like a rising tide raises all boats, growth creates more growth. More people increases demand for everything, which increases business sales, which increases jobs and wages, which increases the value of real estate and household wealth, which increases tax revenue, which allows offering more services to make a state even more appealing.

On the other hand, shrinking can become like the whirlpool over a drain. As the problems increase more people decide to leave, making the problems worsen. As more people go, there are fewer people left behind to make things better. Jobs go away, wages fall, demand drops, real estate prices drop, infrastructure projects stop, services stop and yet taxes have to be raised on the fewer remaining residents.