by Adam Hartung | Nov 3, 2020 | Finance, Investing, Strategy, Trends

In September, 2015 (5 years ago) I wrote that Tesla was going to change global oil demand. Why? Because Tesla had proven there was a market shift toward electric vehicles (EV’s). Yes, the market was small. But every major auto company had seen the trend emerge, and all had EV’s on the drawing tables. Simultaneously, this was showing a shift to “electrification” at the same time that solar energy costs were dropping in price similar to computer chips in the 1990s.

The combination of shifts away from internal combustion engine (ICE) automobiles operating on petroleum, and the growth in renewable energy production from solar and wind was becoming obvious. In sailing, there are small lengths of cloth attached to the sails specifically to obtain an early read on wind direction. These are called “telltales.” Looking at Tesla and growing renewable electricity generation, the telltales gave me confidence to specifically predict it would

really hurt Exxon.

Now, 5 years later, most pundits think the world has reached “peak oil” usage, and demand for oil will only fall.Since 2015 Exxon’s equity value (XOM) has declined 65%. Due to declining demand, the company is being forced to restructure and possibly

cut its dividend as the company shrinks.

Some would look only at short-term issues like the pandemic, but the economy in China has fully recovered – yet its demand for oil has not. Or some might say that oil prices are down only because Saudi Arabia and Russia are battling over market share – but this only portends more bad news for Exxon because 2 giants with the lowest cost battling for share will only make it harder for Exxon to sell products, even at a lower price and little or no margin.

Unfortunately, the pandemic has created an acceleration in the trends that are dooming profits for oil companies like Exxon. Once business happened in physical meetings where we transported ourselves by auto or plane fueled by oil. Now, meetings are being held on-line, virtually. Increasingly individuals, and companies, have learned not only how to use this technology but that they are more productive. Less wasted commuting time, less wasted hallway conversation time, fewer interruptions, and a recognition that it is possible to cut meeting time allowing attendees to better streamline work and decision-making. Speaking of work, virtual meetings are leading to better employee concentration due to better scheduling of time for meetings, and scheduling time for individual work.

Recall 2010 and the effort put into driving to work, or flying to meetings. Exxon, GM, Ford, Boeing, United Airlines and American Airlines were economic leaders, reflecting the work methods of the Industrial Era. Exxon was one of the 30 stocks on the Dow Jones Industrial Average. But the Great Recession had taken GM off the Dow, and now declining oil demand has removed Exxon – following the path I previously predicted.

Look at current 11/2020 market capitalizations:

Exxon – $133B

General Motors – $49B

Ford – $31B

Boeing – $83B

United Airlines – $10B

American Airlines – $6B

The world has changed. Trends have prevailed. We are now more mobile-oriented, work more asynchronously and use

more gig resources. Now we connect by Zoom and travel on electrons.

REUTERS/Lucy Nicholson

Zoom market cap – $146B

Tesla market cap – $380BWhy this walk down the path of recent history? Markets shift – often a lot faster than we would like to imagine. The economic hurt on those left behind is enormous. The opportunity for new leaders even more enormous. On the back end of trends is a LOT of pain. On the front end of trends is a lot of happy, happy. It is incredibly important to pick out the telltales and incorporate them into your planning. Earlier rather than later.Let trends direct your investments and your business decisions – look forward not backward. You want to be Zoom or Tesla (or own the stocks,) not Exxon, GM or Boeing (nor own those stocks.)

If you don’t have a clear line of sight to the future, ask for help – it’s my job. Do you remember anyone else predicting this enormous shift back in 2015? Back then oil was $100/barrel and Exxon was trading at $100/share. More pundits were expecting the future to look like the past than to make a radical shift. But we are always looking at the early telltales, always developing new scenarios, always preparing for market shifts and their implications.

Did you see the trends, and were you expecting the changes that would happen to oil demand? It IS possible to use trends to make good forecasts, and prepare for big market shifts. If you don’t have time to do it, maybe you should contact us!! We track hundreds of trends, and are experts at developing scenarios applied to your business to help you make better decisions.

Or, to keep up on trends, subscribe to our weekly podcasts and posts on trends and how they will affect the world of business at www.SparkPartners.comTRENDS MATTER. If you align with trends your business can do GREAT! Are you aligned with trends? What are the threats and opportunities in your strategy and markets? Do you need an outsider to assess what you don’t know you don’t know? You’ll be surprised how valuable an inexpensive assessment can be for your future business. Click for Assessment info.

Give us a call or send an email. [email protected] 847-331-6384

by Adam Hartung | Sep 1, 2020 | Finance, Investing, Strategy, Trends

On 8/31/20, the Dow Jones Industrial Average went through a change in composition. Out went Exxon, Pfizer and Raytheon. In came Salesforce.com, Amgen and Honeywell. This is the 8th time the Index components have changed this decade, the 13th time since 2000 and the 55th change since created in 1896. So changes are not uncommon. But, are they meaningful? Ask any academic and you’ll get a resounding “NO.” There is no stated criteria for selection, no metrics for inclusion, no breadth to the number of companies (which has changed significantly over time,) and not even a weighting for market capitalization! The DJIA has no relationship to “the market,” which could well be measured better by the S&P 500, or the Russell 3000. And it doesn’t even link to any specific industry! To academics, “the Dow” is just a random number that reflects nothing worth measuring!!

The DJIA is (currently) a group of 30 stocks selected by the editors of Dow Jones (publisher of the Wall Street Journal, owned by News Corp – which also owns Fox News – and controlled by Rupert Murdock). Despite its lack of respect by academics and money managers, because of its age – and the prestige of being selected by these editors – being on the DJIA has been considered somewhat revered. Think of it as an “editorial award of achievement” for size, profitability and perceived stability. For these reasons, over time many investors have believed the index represents a low–risk way to invest in corporations and grow their wealth.

So the daily value of the DJIA is pretty much meaningless. And being on the DJIA is also pretty much meaningless. But, investors have followed this index every trading day for 124 years. So, it is at least interesting. And that’s because it is a track on what these editors think are important very long-term economic trends.

The original Index composition looks NOTHING like 2020. American Cotton Oil Company, American Spirits Manufacturing Company, American Sugar Refining Company, American Tobacco Company, Chicago Gas Light and Coke, General Electric, Leclede Gas, National Lead, Pacific Mail Steamship Company, Tennessee Coal Iron and Railroad Company, United State Cordage Company and United States Leather Company. Familiar household names? This initial list represents the era in 1896 – an agrarian economy just on the cusp of coming into the industrial age. Not forward looking, but rather somewhat reflective of what were the biggest parts of the economy historically with a not forward.

Over 124 years lots of companies left the DJIA — were replaced – and many replacements left. Some came on, went off, and came back on again – such as AT&T, Exxon (formerly Standard Oil of New Jersey) and Chevron (formerly Standard Oil of California.) Even the vaunted GE was inducted in 1899, only to be removed in 1901 – then added back in 1907 where it stayed until CEO Jeff Immelt imploded the company and it was removed for good in 2018.

But, there has been a theme to the changes. Originally, the index was largely agricultural companies. As the economy changed, the Index rotated into commodity companies like gas, coal, copper and nickel – the materials leading to a new era of tools. This gave way to component manufacturers, dominated by the big steel companies, which created the industrial era. Which, of course, led to big manufacturing companies like 3M and IBM. And, along the way, there was recognition for growth in new parts of the economy, by adding consumer goods companies like P&G, Coca-Cola, McDonald’s, Kraft (since removed,) and Nike along with retailers like Sears (later removed,) Walmart, Home Depot and Walgreens. The massively important role of financial services to the economy was reflected by including Travelers, JPMorgan Chase, American Express, Visa and Goldman Sachs. And as health care advanced, the Index added pharmaceutical companies like Pfizer, Johnson & Johnson and Merck.

Obviously, the word “industrial” no longer has any meaning in the Dow Jones Industrial Index.

Reading across the long history of the DJIA one recognizes the editors’ willingness to try and reflect what was growing in the American economy. But in a laggard way. Not selecting companies too early, preferring instead to see that they make a big difference and remain important for many years. And a tendency to keep them on the index long after the bloom is off the rose – like retaining Kraft until 2008 and still holding onto P&G and Coke today.

The bias has always been to be careful about adding companies, lest they not be sustainable. And not judge too hastily the demise of once great companies. Disney wasn’t added until 1991, long after it was an established entertainment leader. Boeing was added in 1987, after pioneering aviation for 30 years. Microsoft added in 1999, well after it had won the PC war. Thus, the index is a “lagging index.” It reflects a big chunk of what was great, while slowly adding what has recently been great – and never moving too quickly to add companies that just might be tomorrow’s leaders.

Sears added in 1924, wasn’t removed until 1999 when its viability is questionable. Phillip Morris Tobacco (became Altria) was added in 1985, and hung around until 2008 — long after we knew cigarettes were deadly and leadership didn’t know how to do anything else. Even today we see that United Aircraft was added in 1939, which became United Technologies in 1976 and then via merger Raytheon in 2020 – before it is now removed, as all things aircraft are screeching to a pandemic halt. And Boeing is still on the Index despite the 737 fiasco and plunging sales. IBM was added in 1939, and through the 1970s it was a leader in office equipment creating the computer industry. But IBM after years of declining sales and profits isn’t really relevant any longer, yet it is still on the Index.

As for adding growing stars, GM stays on the Index until it goes bankrupt, but Tesla is yet to make consideration (largely due to lack of profit history.) Likewise, Walmart remains even though the “big gun” in retail is obviously Amazon.com (another lacking the size and longevity of profits the editors like.) McDonald’s stays on the list, despite no growth for years and even as the Board investigates its HR department for hiding abhorrent leadership behavior – while Starbucks is eschewed. And Cisco is there, while we all use Zoom for pandemic-driven virtual meetings.

So what can we take away from today’s changes? First, the Index has changed dramatically over 20 years to reflect electronic technology. IBM, Microsoft and Apple are now joined by Salesforce. Pharma company Pfizer is being replaced by bio-pharma company Amgen in a nod to the future, although almost 40 years after Genentech went public. Exxon disappears as oil prices fall to sub-zero, demand declines globally and electric cars are on the cusp of taking market leadership. And conglomerate Honeywell is added just to show the editors still think conglomerates matter – even if GE has nearly disintegrated.

Is any of this meaningful? I don’t really think so. As an award for past performance, it’s a nice token to make the list. As business leaders, however, we need to be a LOT more concerned about developing businesses for the future, based on trends, than is indicated by the components of the DJIA. Driving revenue growth and higher margins comes from doing the next big thing, not the last big thing. And, as investors, if you want to make outsized returns you have to know that a basket of largely laggards (Apple, Microsoft and Salesforce excepted) is not the way to build your retirement nest. Instead, you have to invest in companies that are creating the future, making the trends a reality for businesses and consumers. Think FAANG.

Nonetheless, after 124 years it is still sort of interesting. I guess most of us do still care what the editors of big news companies think.

TRENDS MATTER. If you align with trends your business can do GREAT! Are you aligned with trends? What are the threats and opportunities in your strategy and markets? Do you need an outsider to assess what you don’t know you don’t know? You’ll be surprised how valuable an inexpensive assessment can be for your future business (https://adamhartung.com/assessments/)

Give us a call or send an email. [email protected]

by Adam Hartung | Jul 22, 2020 | Disruptions, Innovation, Leadership, Marketing, Trends

As the pandemic dropped on the USA with full force mid-April the price of oil dropped to less than $0. OK, it was something of a fluke. Demand dropped so fast that supply couldn’t fall fast enough, so oil was flowing into refineries and tanks and pipelines so fast that nobody knew where to put it – and that resulted in suppliers having to pay someone to take their oil.

But… the point was very real. Oil prices depend on demand – every bit as much as supply. Even though for a generation we’ve taken growing oil demand for granted, and focused on how to create additional supply, it is a fact that NOW declining demand will limit the value of oil and gas (which is, after all, a commodity.) The TREND has changed course, with demand in the USA barely, or not, growing – and globally demand growth primarily all in Asia (mostly China.) Overall, supply growth has beaten demand growth by a wide margin, and prices are not only low now – they will likely go lower. Even oil company CEOs are predicting US production will decline – but to lower demand

In 2015, I predicted that Tesla could put a big hurt on Exxon. Most people thought that was a joke. Tesla was a fraction the size of GM, and “small potatoes” in the car industry. Meanwhile Exxon was one of the world’s largest oil producers and refiners. That really would be a very small David smacking a very big Goliath – and with a very small rock. But what I pointed out in 2015 was that traditional analysts predicted a very gradual growth in electric cars, and a continued growth in petroleum powered cars, and pretty much constant growth in oil & gas consumption with economic growth. In other words,analysts were using old assumptions all around and expecting only a tiny impact from a few weirdos buying electric cars.

But I asked, what if those assumptions were wrong? In 2015, the world was awash in oil, inventories were then at record levels, and electric car sales were taking off. And the truth was, a lot was happening to reduce demand for oil. Renewable energy programs, conservation, and a change in economic activity from basic manufacturing and commodity processing to a knowledge economy. These trends were all putting big dampers on oil demand. And electric auto sales were poised for a big boom. I predicted demand for oil would drop substantially, inventories would skyrocket and industry problems would worsen as prices cratered.

Uh-hum – what was the price of oil in April?

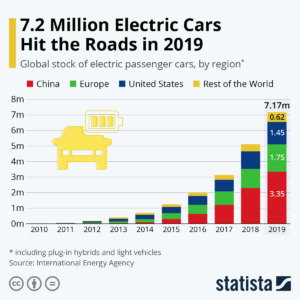

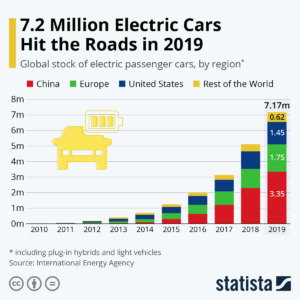

In 2009, I made the case that electric cars were a small base, but that geometric demand growth would make them an important economic impact . Today, most Americans still think that’s the case. In 2009 less than 100,000 new cars were electric. But by 2015, over 1 million electric cars had been sold. Then, with the help of game changers like the Tesla Model 3 in 2019 sales exceeded 7 million! A 7-fold increase in 5 years, or nearly 50%/year market growth!!

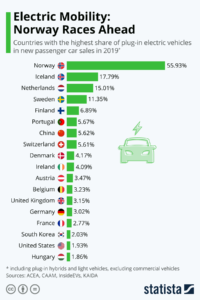

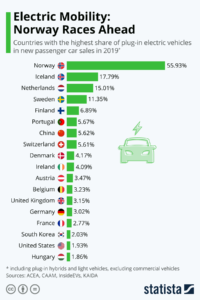

Americans aren’t aware of this phenomenon largely because the big growth centers are outside the USA. Where electrics are ~2% of US car sales, in some European countries they are well over 10% of the market. Even in China they represent over 5% of sales!

Remember what I said above about demand growth depending on China? Look again at who’s buying the most electric cars.

Lessons:

1 – Never think your product is beyond attack by market forces. Be paranoid.

2 – Very small, fringe competition can sneak up and steal your market faster than you think.

3 – Fringe changers don’t have to take a huge market share to make a BIG impact on your market and pricing.

4 – Disruptive events favor the upstarts, who are on trend, and hurt big incumbents, who depend on “business as usual.”

5 – Don’t expect markets to “return to normal.” Markets always move forward, with trends.

6 – Don’t plan from the past, plan for the future – and pay attention to disruptions, they can break you.

TRENDS MATTER. If you align with trends your business can do GREAT! Are you aligned with trends? What are the threats and opportunities in your strategy and markets? Do you need an outsider to assess what you don’t know you don’t know? You’ll be surprised how valuable an inexpensive assessment can be for your future business (https://adamhartung.com/assessments/)

Give us a call or send an email. Adam @Sparkpartners.com

by Adam Hartung | Oct 30, 2017 | Food and Drink, Growth Stall, Investing, Leadership, Retail

Understand Growth Stalls So You Can Avoid GM, JCPenney and Chipotle

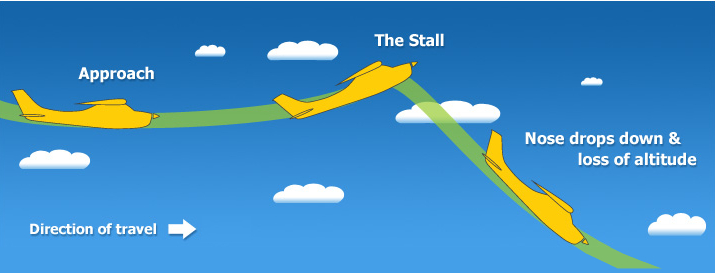

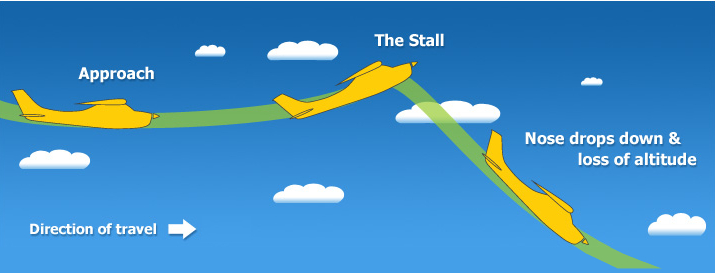

Companies, like aircraft, stall when they don’t have enough “power” to continue to climb.

Everybody wants to be part of a winning company. As investors, winners maximize portfolio returns. As employees winners offer job stability and career growth. As communities winners create real estate value growth and money to maintain infrastructure. So if we can understand how to avoid the losers, we can be better at picking winners.

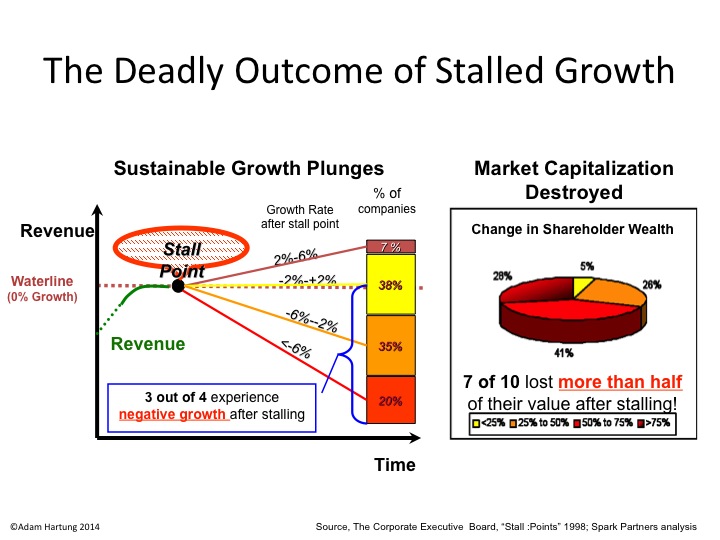

It has been 20 years since we recognized the predictive power of Growth Stalls. Growth Stalls are very easy to identify. A company enters a Growth Stall when it has 2 consecutive quarters, or 2 successive quarters vs the prior year, of lower revenues or profits. What’s powerful is how this simple measure indicates the inability of a company to ever grow again.

Only 7% of the time will a company that has a Growth Stall ever grow at greater than 2%/year. 93% of these companies will never achieve even this minimal growth rate. 38% will trudge along with -2% to 2% growth, losing relevancy as it develops no growth opportunities. But worse, 55% of companies will go into decline, with sales dropping at 2% or more per year. In fact 20% will see sales drop at 6% or more per year. In other words, 93% of companies that have a Growth Stall simply will not grow, and 55% will go into immediate decline.

Growth Stalls happen because the company is somehow “out of step” with its marketplace. Often this is a problem with the product line becoming less desirable. Or it can be an increase in new competitors. Or a change in technology either within the products or in how they are manufactured. The point is, something has changed making the company less competitive, thus losing sales and/or profits.

Unfortunately, leadership of most companies react to a Growth Stall by doubling down on what they already do. They vow to cut costs in order to regain lost margin, but this rarely works because the market has shifted. They also vow to make better products, but this rarely matters because the market is moving toward a more competitive product. So the company in a Growth Stall keeps doing more of the same, and fortunes worsen.

But, inevitably, this means someone else, some company who is better aligned with market forces, starts doing considerably better.

This week analysts at Goldman Sachs lowered GM to a sell rating. This killed a recent rally, and the stock is headed back to $40/share, or lower, values it has not maintained since recovering from bankruptcy after the Great Recession. GM is an example of a company that had a Growth Stall, was saved by a government bailout, and now just trudges along, doing little for employees, investors or the communities where it has plants in Michigan.

Tesla- enough market power to gain share “uphill”?

By understanding that GM, Ford and Chrysler (now owned by Fiat) all hit Growth Stalls we can start to understand why they have simply been a poor place to invest one’s resources. They have tried to make cars cheaper, and marginally better. But who has seen their fortunes skyrocket? Tesla. While GM keeps trying to make a lot of cars using outdated processes and technologies Tesla has connected with the customer desire for a different auto experience, selling out its capacity of Model S sedans and creating an enormous backlog for Model 3. Understanding GM’s Growth Stall would have encouraged you to put your money, career, or community resources into the newer competitor far earlier, rather than the no growth General Motors.

This week, JCPenney’s stock fell to under $3/share. As JCPenney keeps selling real estate and clearing out inventory to generate cash, analysts now say JCPenney is the next Sears, expecting it to eventually run out of assets and fail. Since 2012 JCP has lost 93% of its market value amidst closing stores, laying off people and leaving more retail real estate empty in its communities.

In 2010 JCPenney entered a Growth Stall. Hoping to turn around the board hired Ron Johnson, leader of Apple’s retail stores, as CEO. But Mr. Johnson cut his teeth at Target, and he set out to cut costs and restructure JCPenney in traditional retail fashion. This met great fanfare at first, but within months the turnaround wasn’t happening, Johnson was ousted and the returning CEO dramatically upped the cost cutting.

The problem was that retail had already started changing dramatically, due to the rapid growth of e-commerce. Looking around one could see Growth Stalls not only at JCPenney, but at Sears and Radio Shack. The smart thing to do was exit those traditional brick-and-mortar retailers and move one’s career, or investment, to the huge leader in on-line sales, Amazon.com. Understanding Growth Stalls would have helped you make a good decision much earlier.

This recent quarter Chipotle Mexican Grill saw analysts downgrade the company, and the stock took another hit, now trading at a value not seen since the end of 2012. Chipotle leadership blamed bad results on higher avocado prices, temporary store closings due to hurricanes, paying out damages due to a “one time event” of hacking, and public relations nightmares from rats falling out of a store ceiling in Texas and a norovirus outbreak in Virginia. But this is the typical “things will all be OK soon” sorts of explanations from a leadership team that failed to recognize Chipotle’s Growth Stall.

Prior to 2015, Chipotle was on a hot streak. It poured all its cash into new store openings, and the share price went from $50 from the 2006 IPO to over $700 by end of 2015; a 14x improvement in 9 years. But when it was discovered that ecoli was in Chipotle’s food the company’s sales dropped like a stone. It turned out that runaway growth had not been supported by effective food safety processes, nor effective store operations processes that would meet the demands of a very large national chain.

Prior to 2015, Chipotle was on a hot streak. It poured all its cash into new store openings, and the share price went from $50 from the 2006 IPO to over $700 by end of 2015; a 14x improvement in 9 years. But when it was discovered that ecoli was in Chipotle’s food the company’s sales dropped like a stone. It turned out that runaway growth had not been supported by effective food safety processes, nor effective store operations processes that would meet the demands of a very large national chain.

But ever since that problem was discovered, management has failed to recognize its Growth Stall required a significant set of changes at Chipotle. They have attacked each problem like it was something needing individualized attention, and could be rectified quickly so they could “get back to normal.” And they hoped to turn around public opinion by launching nationwide a new cheese dip product in 2017, despite less than good social media feedback on the product from early customers. They kept attempting piecemeal solutions when the Growth Stall indicated something much bigger was engulfing the company.

What’s needed at Chipotle is a recognition of the wholesale change required to meet customer demands amidst a shift to more growth in independent restaurants, and changing millennial tastes. From the menu options, to app ordering and immediate delivery, to the importance of social media branding programs and customer testimonials as well as demonstrating commitment to social causes and healthier food Chipotle has fallen out-of-step with its marketplace. The stock has now lost 66% of its value in just 2 years amidst sales declines and growth stagnation.

We don’t like to study losers. But understanding the importance of Growth Stalls can be very helpful for your career and investments. If you identify who is likely to do poorly you can avoid big negatives. And understanding why the market shifted can lead you to finding a job, or investing, where leadership is headed in the right direction.

Adam's book reveals the truth about how to use strategy to outpace the competition.

Follow Adam's coverage in the press and in other media.

Follow Adam's column in Forbes.

by Adam Hartung | Feb 7, 2017 | Investing, Trends

The vast majority of individual investors have no idea how to pick stocks. So they often let someone else invest for them, and pay a hefty fee of anywhere from 1% to 5% of their assets annually. Or they buy some sort of fund or portfolio index, where they pay the fund manager usually more than 1% of assets for managing the fund. In the worst case, they pay the financial advisor their fee, and then the advisor buys a fund for the investor – which has that investor paying anywhere from 2% to 8% or even 10% of assets annually for investment advice.

Yet, we know that few asset managers can beat “the market,” whether measured by the DJIA (Dow Jones Industrial Average) or the S&P 500. A study in Europe showed no active manager beat their benchmark over 10 years, and in the U.S. 80% to 90% of fund managers failed to do as well as their benchmarks. And there are studies showing that even if a manager beats their index, after accounting for management fees and costs the investors almost never beat the market.

Any individual could buy the market index by simply opening an on-line account at any discount brokerage, for a very small cost, and buying the exchange traded fund (ETF) for the Dow (DIA – often called “Diamonds”) or the S&P (SPDR – often called “Spiders”). Thus, individual investors can do as well as the “market” at very, very low cost. Most academics will tell investors to not try and beat the market, because the market is wildly inefficient and investors are always without full knowledge of the company, and thus buy these indices.

But most investors are lured by the notion of “beating the market” so they pay the high fees in order to – hopefully – have someone do a better job of investing. And they end up disappointed.

Investors can “beat the market,” but it requires a different approach to investing than fund managers use. And it is far more suited to individuals, with long-term horizons – and it avoids paying those outrageous financial services fees. To be a long-term high-return investor individuals simply need to invest in trends.

247wallst.com published an article stating the editors had seen a report published by Jefferies, sent to them by Bloomberg, which claimed that 20% of all the gains in the total stock market since 1924 (some 93 years) were created by a mere 14 stocks. This sort of blows up all academic theories about investing in portfolios, as it drives home that most market returns are driven by a small collection of companies. Individuals would be better off if they invested in just a few stocks, rather than all stocks. But this means you have to know which stocks to own.

You would think this might be hard, until you look at the list of 14. There is a striking pattern. All were simply the biggest, most powerful companies leading an important, large trend. So if you identified the trend, and invested in the largest company creating that trend, you would do really well. And because these are large companies, investors aren’t carrying the risk of small companies that could be competitively destroyed by larger players. Interestingly, identifying these trends and the large players really isn’t that hard. Nor is it hard to recognize when the trend is ending, and it is time to sell.

We can understand this by looking at the list of 14 not by how much market gain they created, but rather historically when the majority of those gains occurred.

People have enjoyed smoking tobacco since at least the 1500s. Long before anyone knew about the chemical affects and shortened lifespan people simply enjoyed the practice of smoking and the impact nicotine had on them. As tobacco spread from France to England, eventually it moved to the U.S. and was the first ever cash crop – grown in America for sale in Europe. For literally hundreds of years the trend toward tobacco consumption grew. So, it is easy to understand why investing in Phillip Morris, which was renamed Altria, was a good move. As long as people kept buying more cigarettes investing in the largest cigarette company was a good way to increase your returns.

For hundreds of years people used whale oil and similar animal products for candles and lanterns. Wood and coal were used for cooking. But then in 1859 oil was successfully found, and it changed the world. Oil was far cheaper to produce than animal or vegetable oils and burned more consistently at a higher temperature than those products, wood or coal. And that unleashed a trend toward hydrocarbon production leading to the birth of countless new products. It would not have been hard to see that this trend was going to be very valuable. Thus two other names on the list pop up, Exxon and Chevron. These companies are successors of the original Standard Oil founded by John Rockefeller – which created tremendous returns for investors for many years as oil consumption, and production, grew.

Hydrocarbons were a tremendous contributor to the industrial revolution, allowing manufacturers to use engines in new products, and to improve their manufacturing. One of the earliest, and soon biggest, manufacturers was General Electric, another big value producer on the list of 14. And one of the biggest industrial revolution gains was the automobile, where General Motors became by far the largest producer. Investors who put money into the industrial revolution and the trend toward making things – especially cars – came out very well by buying shares in these two companies.

As the industrial revolution grew the middle class emerged, enjoying a vast improvement in quality of life. This led to the trend of consumerism, as it was possible to make things much cheaper and distribute them wider. Three of the biggest companies that promoted this consumer trend were Johnson & Johnson, Proctor & Gamble and Coca-Cola. All were in different product markets, but all were very big leaders in the growth of consumer products for a 1900s world (especially post-WWII) where people had more money – and the desire to buy things. And all three did very well for their investors.

Soon a new trend emerged with the capability of electronics. First came the advent of instant, modern communications as the telephone emerged. Regardless the cost, there was high value in being able to communicate with someone “now” even if they were in a distant location. Investors in Alexander Bell’s AT&T did quite well as phones made their way across America and around the world.

Soon thereafter mechanical adding machines were greatly improved by using electronics – initially relays – to make tabulations and computations. IBM was an early developer of these machines for commercial use, and very quickly came to dominate the market for computers. It was not long before every company needed a computer, or at least access to use one, in order to compete. Investors in IBM were well rewarded for spotting this trend.

As the market for consumer goods exploded Sam Walton recognized the inefficiency of retail product distribution. He discovered that by owning more stores he could negotiate better with consumer goods manufacturers, purchase products more cheaply and sell them more cheaply. He created the trend toward mass retailing driven by efficiency, and he rapidly demonstrated the ability to drive competitors completely out of many retail markets. Investors who identified this trend toward low-cost retailing of a wide product array made considerable gains by purchasing Wal-Mart shares.

As computers became smaller the market expanded, leading to the development of ever smaller computers. Microsoft created software allowing multiple manufacturers to build machines with interoperability, allowing it to take a dominant position in the trend to computers so small every single person could have one – and indeed eventually felt they could not live without one. Microsoft investors made huge gains as the company practically monopolized this trend and created the personal compute marketplace.

It was Apple that first recognized the trend toward mobility being created by ever faster connection speeds. Mobility would allow for radical changes in how many product markets behaved, and investors who saw this mobility trend were amply rewarded for investing in Apple – the company that became synonymous with internet-enabled products.

And as computing mobility improved it created a trend toward buying at home rather than going to a store. Mail order had almost entirely disappeared, due to lack of timely product fulfillment. But with the internet as the interface, coupled with modern, highly efficient transportation services, Amazon was able to give a rebirth to shopping from home and the e-commerce trend exploded. Investors that recognized Amazon’s vastly lower cost retail model, coupled with the infinite prospects for product variety, have been rewarded for investing in the large on-line retailer.

These 14 companies created 20% of all stock market gains across nearly a century. And each was the dominant competitor in a major trend. Several are no longer on the trend, and even a couple have filed bankruptcy (like AT&T and GM), thus it is easy to recognize why some have done far less well the last decade. The world changed and their business model which once produced excellent returns no longer does. But savvy investors should recognize when a trend has run its course, and drop that company in favor of investing in the leader of a major, new trend.

All investors should be long-term investors. Trying to be a market timer, and a trader, is a fool’s errand. To make high investment returns requires taking a long-term (multi-year) view – not monthly or quarterly. Therefore it is important that when investing in trends they be big trends. Trends that will have a large impact on every business – every person. Trends that can generate tremendous returns for many years.

Not everyone can be a stock picker. Therefore, most investors should probably have a goodly chunk of their money in an ETF. That can be done easily enough as described above. But, if you want to increase your returns to beat the market the key is to invest in companies that are large, and the leaders in a major trend.

What are the big trends today? There is no doubt “social” is a huge trend. How every business and person interacts is changing as the use of social tools increases. This is a global phenomenon, and it is a trend with many years left to extend its impact. Investing in the market leader – Facebook – shows good likelihood of obtaining the kind of returns created by the 14 companies discussed above.

What other trends can you identify that have years yet to go? If you can spot them, and invest in a dominant, large leader then you just may outperform nearly every active fund manager trying to get you to pay their fees.

Prior to 2015, Chipotle was on a hot streak. It poured all its cash into new store openings, and the share price went from $50 from the 2006 IPO to over $700 by end of 2015; a 14x improvement in 9 years. But when it was discovered that ecoli was in Chipotle’s food the company’s sales dropped like a stone. It turned out that runaway growth had not been supported by effective food safety processes, nor effective store operations processes that would meet the demands of a very large national chain.

Prior to 2015, Chipotle was on a hot streak. It poured all its cash into new store openings, and the share price went from $50 from the 2006 IPO to over $700 by end of 2015; a 14x improvement in 9 years. But when it was discovered that ecoli was in Chipotle’s food the company’s sales dropped like a stone. It turned out that runaway growth had not been supported by effective food safety processes, nor effective store operations processes that would meet the demands of a very large national chain.