by Adam Hartung | Apr 2, 2015 | Current Affairs, Defend & Extend, In the Rapids, Innovation, Leadership, Web/Tech

Microsoft launched its new Surface 3 this week, and it has been gathering rave reviews. Many analysts think its combination of a full Windows OS (not the slimmed down RT version on previous Surface tablets,) thinness and ability to operate as both a tablet and a PC make it a great product for business. And at $499 it is cheaper than any tablet from market pioneer Apple.

Meanwhile Apple keeps promoting the new Apple Watch, which was debuted last month and is scheduled to release April 24. It is a new product in a market segment (wearables) which has had very little development, and very few competitive products. While there is a lot of hoopla, there are also a lot of skeptics who wonder why anyone would buy an Apple Watch. And these skeptics worry Apple’s Watch risks diverting the company’s focus away from profitable tablet sales as competitors hone their offerings.

Looking at these launches gives a lot of insight into how these two companies think, and the way they compete. One clearly lives in red oceans, the other focuses on blue oceans.

Blue Ocean Strategy (Chan Kim and Renee Mauborgne) was released in 2005 by Harvard Business School Press. It became a huge best-seller, and remains popular today. The thesis is that most companies focus on competing against rivals for share in existing markets. Competition intensifies, features blossom, prices decline and the marketplace loses margin as competitors rush to sell cheaper products in order to maintain share. In this competitively intense ocean segments are niched and products are commoditized turning the water red (either the red ink of losses, or the blood of flailing competitors, choose your preferred metaphor.)

On the other hand, companies can choose to avoid this margin-eroding competitive intensity by choosing to put less energy into red oceans, and instead pioneer blue oceans – markets largely untapped by competition. By focusing beyond existing market demands companies can identify unmet needs (needs beyond lower price or incremental product improvements) and then innovate new solutions which create far more profitable uncontested markets – blue oceans.

Obviously, the authors are not big fans of operational excellence and a focus on execution, but instead see more value for shareholders and employees from innovation and new market development.

If we look at the new Surface 3 we see what looks to be a very good product. Certainly a product which is competitive. The Surface 3 has great specifications, a lot of adaptability and meets many user needs – and it is available at what appears to be a favorable price when compared with iPads.

But …. it is being launched into a very, very red ocean.

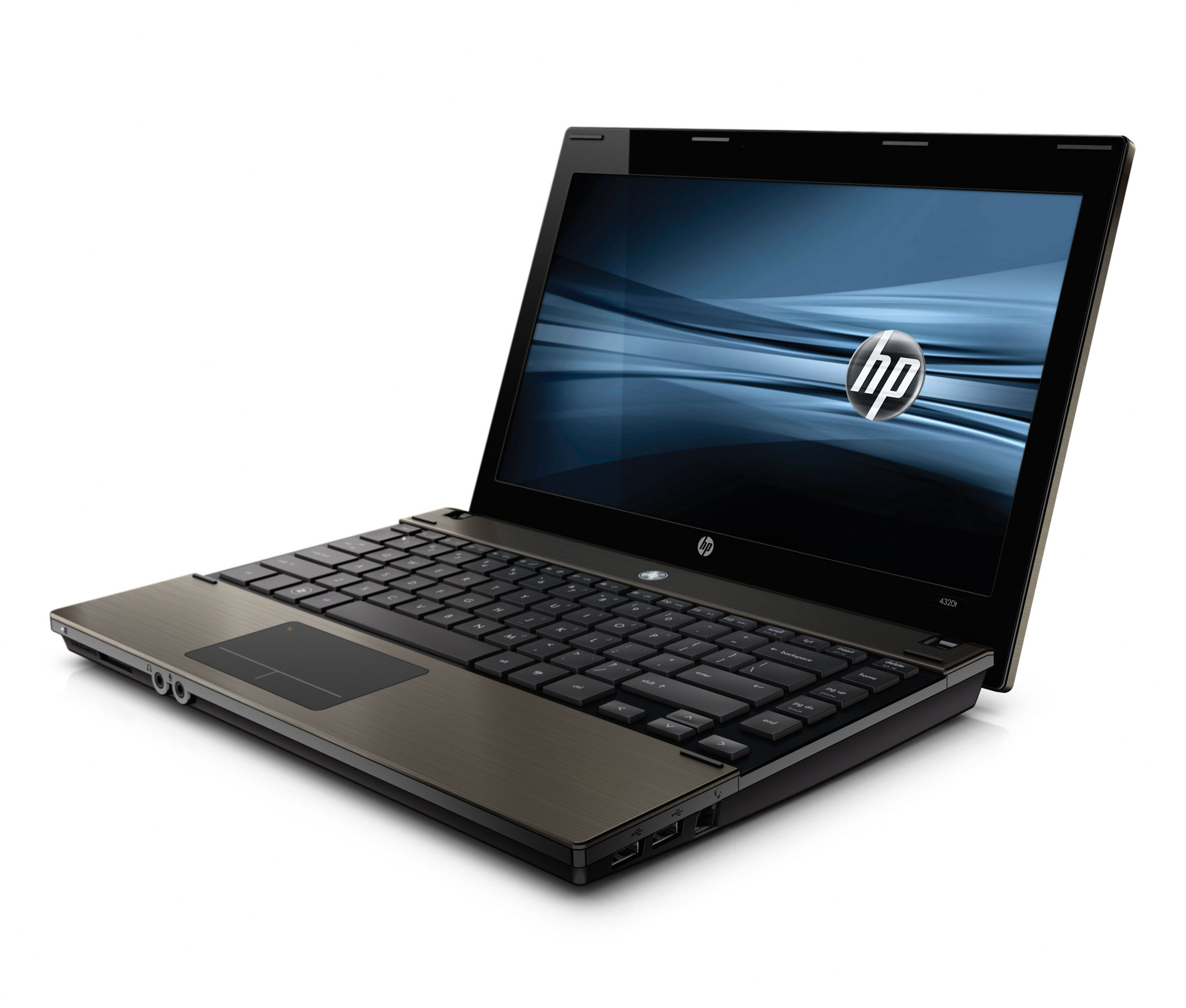

The market for inexpensive personal computing devices is filled with a lot of products. Don’t forget that before we had tablets we had netbooks. Low cost, scaled back yet very useful Microsoft-based PCs which can be purchased at prices that are less than half the cost of a Surface 3. And although Surface 3 can be used as a tablet, the number of apps is a fraction of competitive iOS and Android products – and the developer community has not yet embraced creating new apps for Windows tablets. So Surface 3 is more than a netbook, but also a lot more expensive.

Additionally, the market has Chromebooks which are low-cost devices using Google Chrome which give most of the capability users need, plus extensive internet/cloud application access at prices less than a third that of Surface 3. In fact, amidst the Microsoft and Apple announcements Google announced it was releasing a new ChromeBit stick which could be plugged into any monitor, then work with any Bluetooth enabled keyboard and mouse, to turn your TV into a computer. And this is expected to sell for as little as $100 – or maybe less!

This is classic red ocean behavior. The market is being fragmented into things that work as PCs, things that work as tablets (meaning run apps instead of applications,) things that deliver the functionality of one or the other but without traditional hardware, and things that are a hybrid of both. And prices are plummeting. Intense competition, multiple suppliers and eroding margins.

Ouch. The “winners” in this market will undoubtedly generate sales. But, will they make decent profits? At low initial prices, and software that is either deeply discounted or free (Google’s cloud-based MSOffice competitive products are free, and buyers of Surface 3 receive 1 year free of MS365 Office in the cloud, as well as free upgrade to Windows 10,) it is far from obvious how profitable these products will be.

Amidst this intense competition for sales of tablets and other low-end devices, Apple seems to be completely focused on selling a product that not many people seem to want. At least not yet. In one of the quirkier product launch messages that’s been used, Apple is saying it developed the Apple Watch because its other innovative product line – the iPhone – “is ruining your life.”

Apple is saying that its leaders have looked into the future, and they think today’s technology is going to move onto our bodies. Become far more personal. More interactive, more knowledgeable about its owner, and more capable of being helpful without being an interruption. They see a future where we don’t need a keyboard, mouse or other artificial interface to connect to technology that improves our productivity.

Right. That is easy to discount. Apple’s leaders are betting on a vision. Not a market. They could be right. Or they could be wrong. They want us to trust them. Meanwhile, if tablet sales falter….. if Surface 3 and ChromeBit do steal the “low end” – or some other segment – of the tablet market…..if smartphone sales slip….. if other “forward looking” products like ApplePay and iBeacon don’t catch on……

This week we see two companies fundamentally different methods of competing. Microsoft thinks in relation to its historical core markets, and engaging in bloody battles to win share. Microsoft looks at existing markets – in this case tablets – and thinks about what it has to do to win sales/share at all cost. Microsoft is a red ocean competitor.

Apple, on the other hand, pioneers new markets. Nobody needed an iPod… folks were happy enough with Sony Walkman and Discman. Everybody loved their Razr phones and Blackberries… until Apple gave them an iPhone and an armload of apps. Netbook sales were skyrocketing until iPads came along providing greater mobility and a different way of getting the job done.

Apple’s success has not been built upon defending historical markets. Rather, it has pioneered new markets that made existing markets obsolete. Its success has never looked obvious. Contrarily, many of its products looked quite underwhelming when launched. Questionable. And it has cannibalized its own products as it brought out new ones (remember when iPods were so new there was the iPod mini, iPod nano and iPod Touch? After 5 years of declining iPod sale Apple has stopped reporting them.) Apple avoids red oceans, and prefers to develop blue ones.

Which company will be more successful in 2020? Time will tell. But, since 2000 Apple has gone from nearly bankrupt to the most valuable publicly traded company in the USA. Since 1/1/2001 Microsoft has gone up 32% in value. Apple has risen 8,000%. While most of us prefer the competition in red oceans, so far Apple has demonstrated what Blue Ocean Strategy authors claimed, that it is more profitable to find blue oceans. And they’ve shown us they can do it.

by Adam Hartung | Mar 27, 2015 | Investing, Mobile, Software, Trends, Web/Tech

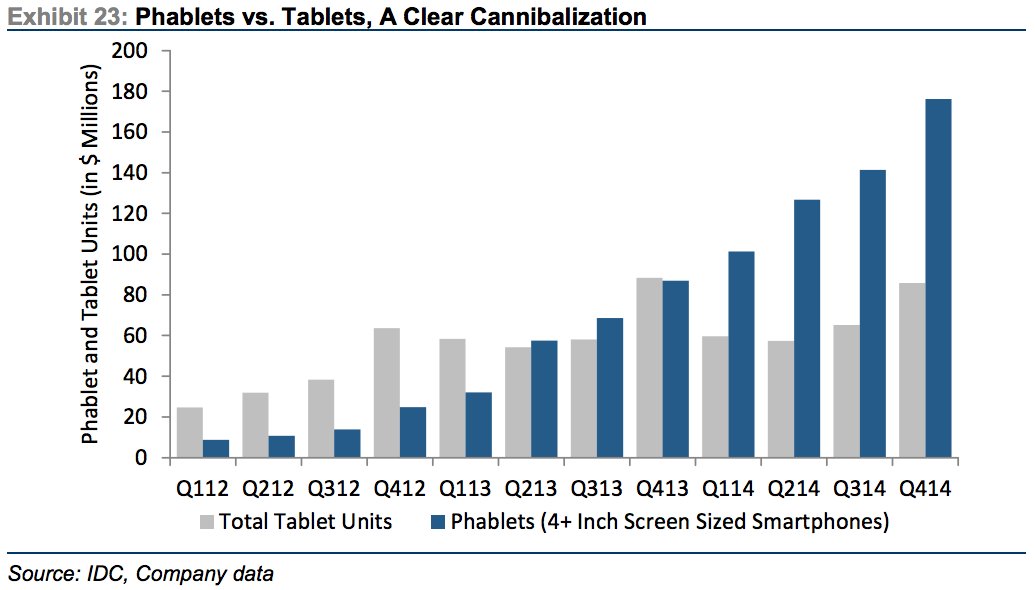

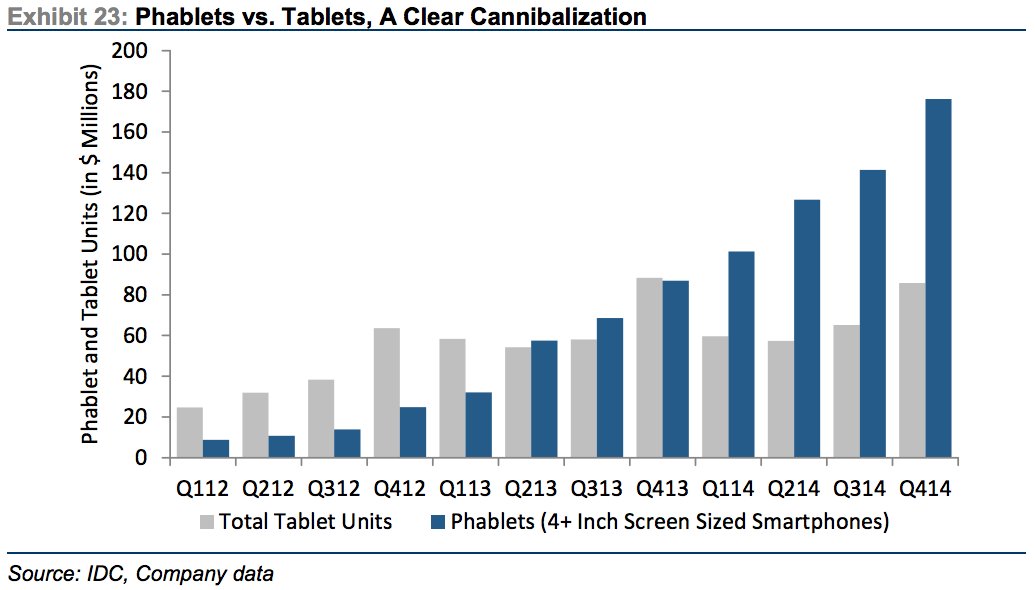

Phablets are a very hot, growing market. Phablets are those huge phones (greater than 4″ screen size) that some people carry around. From almost nothing in 2012, over the last 3 years the market has exploded:

Source: Jay Yarrow, Business Insider http://www.businessinsider.com/in-one-chart-heres-why-the-ipad-business-is-cratering-2015-3?utm_content=&utm_medium=email&utm_source=alerts&nr_email_referer=1

The original creator of this market data, Kulbinder Garcha of Credit Suisse, thinks this demonstrates cannibalization of tablet sales by phablets. And this is supposedly a bad thing for Apple.

But there is another way to look at this. By introducing and promoting a phablet (iPhone 6+ and Galaxy S6,) Apple and Samsung are growing users of mobile media and mobile apps. As the chart shows, growth in tablet sales was nothing compared to what happened when phablets came along. So people who didn’t buy a tablet, and maybe (likely?) wouldn’t, are buying phablets. The market is growing faster with phablets than had they not been introduced, and even if tablet sales shrink Apple and Samsung see revenues continue growing.

Who wins as phablet sales grow? Those who have phablet products in the market, and newer versions in the works.

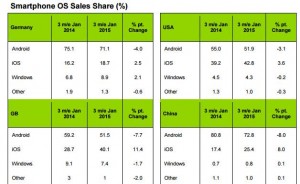

Source: Kantar WorldPanel and Seeking Alpha http://seekingalpha.com/article/3032926-microsoft-the-china-mobile-backed-lenovo-windows-10-smartphone-could-be-a-future-tailwind?ifp=0

As this chart shows, the companies who dominate smartphone sales are those who make Android-based products (#1 is Samsung) and Apple. Microsoft missed the mobile/smartphone trend, and even though it purchased Nokia it has never obtained anything close to double digit share in any market.

Unfortunately for Microsoft enthusiasts, and investors, Microsoft’s Windows10 product is focused first on laptop (PC) users, second on hybrid (products used as both a laptop and tablet), third tablets (primarily the slow-selling Microsoft Surface) and in a far, far trailing position smartphones.

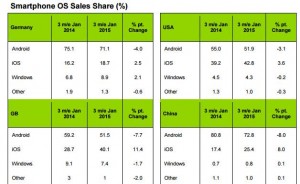

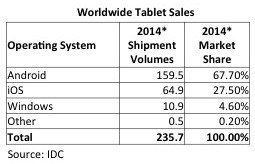

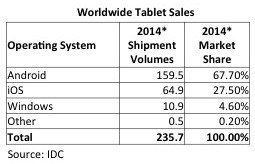

Source: IDC

As data from IDC shows, Surface sales are inconsequential. So the big loser from phablet cannibalization of tablets will be Microsoft. Given its very small user base, and the heavy losses Microsoft has taken on Surface, there is little revenue or cash flow to support an intense competitive effort in a shrinking market. Apple and Samsung will market hard to grow as many sales as possible, and likely will make the tablet products more affordable. Thus one should anticipate Microsoft’s very small tablet share would decline as tablet sales shrink.

This is the problem created when any business misses a major trend.

Microsoft missed the trend to mobile. They didn’t prepare for it in any of their major products, and they let new products, like music player Zune and Lumia phones, languish – and mostly die. By the time Microsoft reacted Apple and Samsung had enormous leads. Microsoft is still trying to play catch-up with its “core” Windows product.

But worse, because it is so far behind, Microsoft’s leaders are unable to forecast where the market will be in 3 years. Consequently they develop products for today’s market, like tablets (and their hybrid products,) which we now see will be obsolete as the market shifts to new products (like phablets.) Because Apple and Samsung already have the new products (phablets) they are prepared to cannibalize the old product sales (tablets) in order to overall grow the marketplace. But Microsoft has no phablet product, really no smartphone product, and will find itself most likely writing off more future Surface products as its tiny market share erodes to nothing.

So this trend to phablets continues to make a Microsoft comeback as a major personal technology competitor problematic. Windows 10 may be coming, but its relevance looks increasingly like that of new Blackberry models. There is little reason to care, because the products are years late and poorly positioned for leading edge customers. Further, developers will already be onto new competitive platforms long before the outdated Microsoft products make it to market. Without share you don’t capture developers, without developers you don’t have a robust app market, without apps you don’t capture customers, without customers you can’t build share — and that’s a terrible whirlpool Microsoft is captured within.

Be sure your business keeps its eyes on trends, and does not wait to react. Waiting can turn out to be deadly.

by Adam Hartung | Feb 12, 2015 | Current Affairs, Disruptions, Innovation, Leadership, Web/Tech

Despite huge fanfare at launch, after a few brief months Google Glass is no longer on the market. The Amazon Fire Phone was also launched to great hype, yet sales flopped and the company recently took a $170M write off on inventory.

Fortune mercilessly blamed Fire Phone’s failure on CEO Jeff Bezos. The magazine blamed him for micromanaging the design while overspending on development, manufacturing and marketing. To Fortune the product was fatally flawed, and had no chance of success according to the article.

Similarly, the New York Times blasted Google co-founder and company leader Sergie Brin for the failure of Glass. He was held responsible for over-exposing the product at launch while not listening to his own design team.

Both these articles make the common mistake of blaming failed new products on (1) the product itself, and (2) some high level leader that was a complete dunce. In these stories, like many others of failed products, a leader that had demonstrated keen insight, and was credited with brilliant work and decision-making, simply “went stupid” and blew it. Really?

Unfortunately there are a lot of new products that fail. Such simplistic explanations do not help business leaders avoid a future product flop. But there are common lessons to these stories from which innovators, and marketers, can learn in order to do better in the future. Especially when the new products are marketplace disrupters; or as they are often called, “game changers.”

Do you remember Segway? The two wheeled transportation device came on the market with incredible fanfare in 2002. It was heralded as a game changer in how we all would mobilize. Founders predicted sales would explode to 10,000 units per week, and the company would reach $1B in sales faster than ever in history. But that didn’t happen. Instead the company sold less than 10,000 units in its first 2 years, and less than 24,000 units in its first 4 years. What was initially a “really, really cool product” ended up a dud.

There were a lot of companies that experimented with Segways. The U.S. Postal Service tested Segways for letter carriers. Police tested using them in Chicago, Philadelphia and D.C., gas companies tested them for Pennsylvania meter readers, and Chicago’s fire department tested them for paramedics in congested city center. But none of these led to major sales. Segway became relegated to niche (like urban sightseeing) and absurd (like Segway polo) uses.

Segway tried to be a general purpose product. But no disruptive product ever succeeds with that sort of marketing. As famed innovation guru Clayton Christensen tells everyone, when you launch a new product you have to find a set of unmet needs, and position the new product to fulfill that unmet need better than anything else. You must have a very clear focus on the product’s initial use, and work extremely hard to make sure the product does the necessary job brilliantly to fulfill the unmet need.

Nobody inherently needed a Segway. Everyone was getting around by foot, bicycle, motorcycle and car just fine. Segway failed because it did not focus on any one application, and develop that market as it enhanced and improved the product. Selling 100 Segways to 20 different uses was an inherently bad decision. What Segway needed to do was sell 100 units to a single, or at most 2, applications.

Segway leadership should have studied the needs deeply, and focused all aspects of the product, distribution, promotion, training, communications and pricing for that single (or 2) markets. By winning over users in the initial market Segway could have made those initial users very loyal, outspoken customers who would recommend the product again and again – even at a $4,000 price.

Segway should have pioneered an initial application market that could grow. Only after that could Segway turn to a second market. The first market could have been using Segway as a golfer’s cart, or as a walking assist for the elderly/infirm, or as a transport device for meter readers. If Segway had really focused on one initial market, developed for those needs, and won that market it would have started a step-wise program toward more applications and success. By thinking the general market would figure out how to use its product, and someone else would develop applications for specific market needs, Segway’s leaders missed the opportunity to truly disrupt one market and start the path toward wider success.

The Fire Phone had a great opportunity to grow which it missed. The Fire Phone had several features making it great for on-line shopping. But the launch team did not focus, focus, focus on this application. They did not keep developing apps, databases and ways of using the product for retailing so that avid shoppers found the Fire Phone superior for their needs. Instead the Fire Phone was launched as a mass-market device. Its retail attributes were largely lost in comparisons with other general purpose smartphones.

The Fire Phone had a great opportunity to grow which it missed. The Fire Phone had several features making it great for on-line shopping. But the launch team did not focus, focus, focus on this application. They did not keep developing apps, databases and ways of using the product for retailing so that avid shoppers found the Fire Phone superior for their needs. Instead the Fire Phone was launched as a mass-market device. Its retail attributes were largely lost in comparisons with other general purpose smartphones.

People already had Apple iPhones, Samsung Galaxy phones and Google Nexus phones. Simultaneously, Microsoft was pushing for new customers to use Nokia and HTC Windows phones. There were plenty of smartphones on the market. Another smartphone wasn’t needed – unless it fulfilled the unmet needs of some select market so well that those specific users would say “if you do …. and you need…. then you MUST have a FirePhone.” By not focusing like a laser on some specific application – some specific set of unmet needs – the “cool” features of the Fire Phone simply weren’t very valuable and the product was easy for people to pass by. Which almost everyone did, waiting for the iPhone 6 launch.

This was the same problem launching Google Glass. Glass really caught the imagination of many tech reviewers. Everyone I knew who put on Glass said it was really cool. But there wasn’t any one thing Glass did so well that large numbers of folks said “I have to have Glass.” There wasn’t any need that Glass fulfilled so well that a segment bought Glass, used it and became religious about wearing Glass all the time. And Google didn’t improve the product in specific ways for a single market application so that users from that market would be attracted to buy Glass. In the end, by trying to be a “cool tool” for everyone Glass ended up being something nobody really needed. Exactly like Segway.

Microsoft recently launched its Hololens. Again, a pretty cool gadget. But, exactly what is the target market for Hololens? If Microsoft proceeds down the road of “a cool tool that will redefine computing,” Hololens will likely end up with the same fate as Glass, Segway and Fire Phone. Hololens marketing and development teams have to find the ONE application (maybe 2) that will drive initial sales, cater to that application with enhancements and improvements to meet those specific needs, and create an initial loyal user base. Only after that can Hololens build future applications and markets to grow sales (perhaps explosively) and push Microsoft into a market leading position.

Microsoft recently launched its Hololens. Again, a pretty cool gadget. But, exactly what is the target market for Hololens? If Microsoft proceeds down the road of “a cool tool that will redefine computing,” Hololens will likely end up with the same fate as Glass, Segway and Fire Phone. Hololens marketing and development teams have to find the ONE application (maybe 2) that will drive initial sales, cater to that application with enhancements and improvements to meet those specific needs, and create an initial loyal user base. Only after that can Hololens build future applications and markets to grow sales (perhaps explosively) and push Microsoft into a market leading position.

All companies have opportunities to innovate and disrupt their markets. Most fail at this. Most innovations are thrown at customers hoping they will buy, and then simply dropped when sales don’t meet expectations. Most leaders forget that customers already have a way of getting their jobs done, so they aren’t running around asking for a new innovation. For an innovation to succeed launchers must identify the unmet needs of an application, and then dedicate their innovation to meeting those unmet needs. By building a base of customers (one at a time) upon which to grow the innovation’s sales you can position both the new product and the company as market leaders.

by Adam Hartung | Feb 7, 2015 | In the Rapids, Innovation, Leadership, Transparency, Web/Tech

Apple was a high flyer. As the stock hit $700, analysts predicted it would reach $1,000. Then Steve Jobs died. He so personified the company that many felt his death left Apple leaderless. So the stock lost 42% of its value dropping to $400.

Apple has now recaptured that lost value, and trades a bit above its former historic high. Apple is the most valuable publicly traded company in America, worth about $700B. For some perspective on just how large this valuation is, it roughly equals the combined values of Dow Jones Industrial Average stalwart, industry leading mega-companies Walmart ($281B #1 retailer,) GE ($242B #1 conglomerate,) McDonalds ($91B #1 restaurant,) and Dupont ($70B #1 chemical.)

Since Apple was on the edge of bankruptcy just 15 years ago, and its value has risen so far, so fast, many people question if it can go much higher. Yes, it’s had a great recent quarter. But can anyone expect this company to continue growing at this pace? Won’t smartphones be commoditized causing Apple to lose share, sales and profits to alternatives? And aren’t its new products like the iWatch sort of “faddish?”

Apple is actually leading another new marketplace development that may well be bigger than any previous market development (digital music, smartphones, tablets) which could well send its value much, much higher. This new market success revolves around developers, beacons, consumers, retailers and payments. Just like we didn’t know we wanted an iPod until we saw one, or an iPhone, new products that exploit the Internet of Things (IoT) is where Apple is again leading the creation of new products and markets.

Start with Apple’s developer ecosystem. No device has any value unless it has applications. Apple created the first smartphone developer network around iOS. Because Android implementations vary based on device manufacturer, Apple’s iOS remains by far the largest installed common device base in the USA, and globally. Thus, developers are attracted in the largest numbers to develop applications for iPhones and iPads running iOS before any other device. To have a sense of the size of this developer base, and the speed with which they develop for Apple products, when Apple launched its own software language for developers called Swift it was downloaded over 11million times in the first month. These developer companies, in total, captured over $25B in revenue just in the 4th quarter from AppStore sales.

Understandably, these developers are constantly creating new products which leverage the installed Apple mobile base. A base which continues to double every few months as globally people buy more iPhones (75million iPhone 6 and 6+ devices sold in the 4th quarter.) And a base growing internationally, as Apple just beat out Louis Vuitton and Hermes to become the #1 luxury brand in China. It is now a virtuous circle, where the more apps developers create the more people want iPhones, and the more iPhones people buy the more developers want to create new apps.

And this is not just consumer apps. Increasingly business systems are being built to use Apple products. Many of these are small to medium size developers and resellers. Additionally, in 2014 Apple and IBM joined forces to create IBM MobileFirst which is building enterprise applications for multiple industries which will allow people to do all their work on iPhones and iPads sold by IBM. Even though IBM has struggled of late, its enterprise application skills have long been a corporate strength, and the first wave of products rolled out in December.

Now focus on iBeacon. Beacons are small electronic devices which transmit a signal that can talk to a smartphone. These can cost anywhere from a few dollars to a nickel, depending upon what they do and signal range. Years ago Apple started developing beacons, and then optimized iOS 8 to selectively and efficiently pick up beacon signals and establish 2-way communications without dissipating the battery. Without a lot of fanfare to the general public, they began rolling out iBeacons several months ago.

Today there are millions of beacons in place. Miami airport uses them to help travelers find gates, food, etc. The New York Metropolitan Museum of Art and Guggenheim Museum use them for wayfinding, virtual guided tours and buying products. The Los Angeles Union Station and zoo, as well as the Orlando Seaworld, uses beacons to aid the customer experience, as this technology has become ready for prime time. Starbucks uses them to help loyal customers place orders. Retail applications are many, including finding products, couponing, product information, pricing and even purchase. Chain Store Age says that 2% of retailers had beacons installed in 2014, but that number will grow to 24% by end of 2015. A 12-fold increase in the installed base, at least.

Additionally, Facebook is now integrating beacons into the Facebook mobile app. This means iPhone users won’t need to download a museum or store app to communicate with beacons for their personal needs. Instead they can communicate via Facebook to find items, know what their friends think of the item, compare prices, etc. When the world’s largest social media platform incorporates beacons Mobile Marketer says this bridges digital and physical marketing, increases personalization in use of beacons, and beacons now accelerate the move to seamless mobile marketing and sales.

So, beacons and your idevice (including your iWatch or other wearable,) with the help of all those developers who are writing apps to bring you information, now make it possible for you to find your way around and learn more about things. And with ApplePay you can actually achieve the “last mile” of concluding the relationship between the business and consumer.

While mobile payment systems have been slow to get started, ApplePay has a lot more going for it. Firstly, it has the support of about all the major bank and card-issuing institutions because they see ApplePay as possibly lowering costs and increasing their revenue. Second, 78% of retailers think mobile pay is better and faster than their current point of sale systems. As a result, 43% of retailers plan to implement ApplePay by the end of 2015.

So, during 2015 we will be able to use beacons to find our way around, use beacons to identify services and products we want, and use beacons to tell us about the services and products either with apps from the location and retailer, or via Facebook mobile. Then we can buy those products immediately with ApplePay.

Even though Apple is a very highly valued company, it is again doing what made it such a big winner. Pioneering entirely new ways for consumers and businesses to get things done. New solutions are happening in all kinds of industries, pioneered by developers big and small. And when it comes to IoT, Apple products are at the center of the next big wave. Ancillary products, like watches and headphones, further support the use of Apple mobile products and the trend to IoT. Apple’s had a great run, but there is ample reason to believe that run has not stopped. There looks to be an entirely new wave of growth as Apple creates new products and solutions we didn’t even know we needed until they were in our hands.

by Adam Hartung | Jan 29, 2015 | Current Affairs, In the Whirlpool, Leadership, Web/Tech

This week Yahoo announced it is spinning off the last of its Alibaba holdings. This is a big deal, because it might well signal the end of Yahoo.

Yahoo created internet advertising. Yahoo was once the #1 home page for browsers across America. But the company has floundered for years, riddled with CEO problems, a contentious Board of Directors and no strategy for dealing with Google which overtook it in all markets.

To much fanfare the Board hired Marissa Mayer, a Google wunderkind we were told, in July, 2012 to mount a serious turnaround. And during her leadership the company’s stock value has tripled – from about $14.50/share to about $43.50. You would think investors would be thrilled and the company would be on the right track.

Only almost all that value creation was due to a stock investment made in 2005 – when Jerry Yang invested $1B to buy 40% of Alibaba. And Alibaba in 2014 became the most valuable IPO in history.

Yahoo today is valued at about $46B. The Alibaba shares being spun out are valued at between $40B and $44B. Which means that after adjusting for the ownership in Yahoo Japan (valued at $2.3B) the core Yahoo ad and portal business is worth between $2B and $4.7B. With just over $1B shares outstanding, that puts a value on Yahoo’s core business of between $2.00-$4.70/share – or about 1/6 to 1/3 the value when Ms. Mayer became CEO.

A highest value of $4.7B for the operating business of Yahoo puts it on par with Groupon. And worth far less than competitors Google ($347B) and Facebook ($212B). Even upstart, and often maligned, social media companies Twitter ($24B) and LinkedIn ($27B) have valuations 5 times Yahoo.

Unfortunately, this latest leader and her team haven’t been any more effective at improving the company’s business than previous regimes. Under CEO Mayer Yahoo used gains from Alibaba’s valuation to invest about $2.1B in 49 outside companies – with $2B of that being acquisitions of technology companies Flurry ($200M), BrightRoll ($640M) and Tumblr ($1.1). Under the most optimistic view of Yahoo, leadership spent 40% of the company’s value in acquisitions that have made no difference to ad revenues or profits.

In fact, Yahoo’s business revenues, and profits, have declined for 6 consecutive quarters. Despite the CEO’s mandate that employees could no longer work from home. A kerfuffle that proved yet another management distraction, and apparently an effort to cut staff without it looking like a layoff.

Meanwhile there have been big efforts to boost people going to the Yahoo portal. Such as hiring broadcaster Katie Couric to beef up the news section, and former New York Times tech columnist David Pogue to deepen tech coverage and New York Times Magazine political writer Matt Bai to draw in more readers. But these have done nothing to move the needle.

Consistently declining display advertising has left search ads a bigger, and more profitable, business. And while Yahoo’s CEO has been teasing ad agencies that she might begin another big brand campaign, including TV, to bring Yahoo more attention – and hopefully more advertisers – there is no evidence anyone cares as more and more dollars flow to “programmatic” ad buying where Google is king. In the digital ad marketplace Google has 31% share, Facebook 7.75% share and Yahoo a meager 2.36% share.

Soon there will be little left of the once mighty Yahoo. It has pretty much lost relevancy. Large investors are crying for a merger with AOL, whose inability to grow its portal, ad and media businesses has left its market cap at a mere $3.7B. But combining two companies that are market irrelevant, and declining, will probably have the same outcome as happened when merging KMart and Sears. The Yahoo growth stall remains intact, and revenues will decline along with profits as the market continues shifting to powerful and growing competitors Google, Facebook and other social media companies. Only now Yahoo’s leaders won’t have the Alibaba value mountain to hide behind

by Adam Hartung | Jan 22, 2015 | Current Affairs, Defend & Extend, Games, In the Swamp, Innovation, Leadership, Software, Web/Tech

Yesterday Microsoft conducted a pre-launch of Windows 10, demonstrating its features in an effort to excite developers and create some buzz before consumer launch later in 2015.

By and large, nobody cared. Were you aware of the event? Did you try to watch the live stream, offered via the Microsoft web site? Were you eager to read what people thought of the product? Did you look for reviews in the Wall Street Journal, USA Today and other general news outlets?

Microsoft really blew it with Windows 8 – which is the second most maligned Windows product ever, exceeded only by

Vista. But that wasn’t hard to predict, in June, 2012. Even then it was clear that Windows 8, and Surface tablets, were designed to defend and extend the installed Windows base, and as such the design precluded the opportunity to change the market and pull mobile users to Microsoft.

And, unfortunately, that is how Windows 10 has been developed. At the event’s start Microsoft played a tape driving home how it interviewed dozens and dozens of loyal Windows customers, asking them what they didn’t like about 8, and what they wanted in a Windows upgrade. That set the tone for the new product.

Microsoft didn’t seek out what would convert all those mobile users already on iOS or Android to throw away their devices and buy a Microsoft product. Microsoft didn’t ask its defected customers what it would take to bring them back, nor did it ask the over 50% of the market using Windows 7 or older products what it would take to get them to go to Windows mobile rather than an iPad or Galaxy tablet. Nope. Microsoft went to its installed base and asked them what they would like.

Imagine it’s 1975 and for two decades you have successfully made and sold small offset printing presses. Every single company of any size has one in their basement. But customers have started buying really simple, easy to use Xerox machines. Fewer admins are sending even fewer jobs to the print shop in the basement, as they choose to simply run off a bunch of copies on the Xerox machine. Of course these copies are more expensive than the print shop, and the quality isn’t as good, but the users find the new Xerox machines good enough, and they are simple and convenient.

What are you to do if you make printing presses? You probably need to find out how you can get into a new product that actually appeals to the users who no longer use the print shop. But, instead, those companies went to the print shop operators and asked them what they wanted in a new, small print machine. And then the companies upgraded their presses and other traditional printing products based upon what that installed base recommended. And it wasn’t long before their share of printing eroded to a niche of high-volume, and often color, jobs. And the commercial print market went to Xerox.

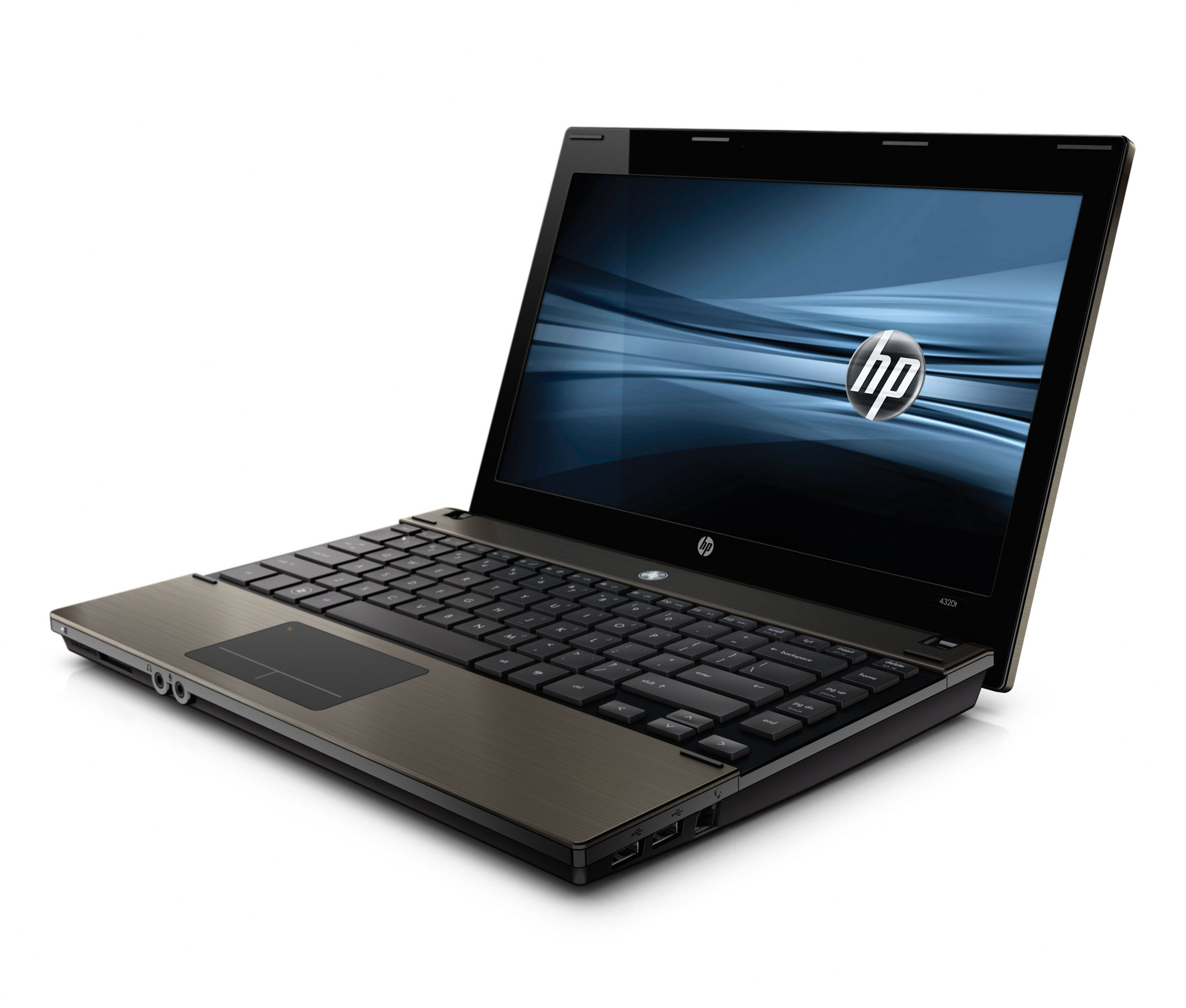

That’s what Microsoft did with Windows 10. It asked its installed base what it wanted in an operating system. When the problem isn’t the installed base, its the substitute product that is killing the company. Microsoft didn’t need input from its installed base of loyal users, it needed input from people who have quit using HP laptops in favor of iPads.

There are a lot of great new features in Windows 10. But it really doesn’t matter.

The well spoken presenters from Microsoft laid out how Windows 10 would be great for anyone who wants to go to an entirely committed Windows environment. To achieve Microsoft’s vision of the future every one of us will throw away our iOS and Android products and go to Windows on every single device. Really. There wasn’t one demonstration of how Windows would integrate with anything other than Windows. And there appeared on intention of making the future an interoperable environment. Microsoft’s view was we would use Windows on EVERYTHING.

Microsoft’s insular view is that all of us have been craving a way to put Windows on all our devices. We’ve been sitting around using our laptops (or desktops) and saying “I can’t wait for Microsoft to come out with a solution so I can throw away my iPhone and iPad. I can’t wait to tell everyone in my organization that now, finally, we have an operating system that IT likes so much that we want everyone in the company to get rid of all other technologies and use Windows on their tablets and phones – because then they can integrate with the laptops (that most of us don’t use hardly at all any longer.)”

Microsoft even went out of its way to demonstrate how well Win10 works on 2-in-1 devices, which are supposed to be both a tablet and a laptop. But, these “hybrid” devices really don’t make any sense. Why would you want something that is both a laptop and a tablet? Who wants a hybrid car when you can have a Tesla? Who wants a vehicle that is both a pick-up and a car (once called the El Camino?) Microsoft thinks these are good devices, because Microsoft can’t accept that most of us already quit using our laptop and are happy enough with a tablet (or smartphone) alone!

Microsoft presenters repeatedly reminded us that Windows is evolving. Which completely ignores the fact that the market has been disrupted. It has moved from laptops to mobile devices. Yes, Windows has a huge installed base on machines that we use less and less. But Windows 10 pretends that there does not exist today an equally huge, and far more relevant, installed base of mobile devices that already has millions of apps people use every single day over and over. Microsoft pretended as if there is no world other than Windows, and that a more robuts Windows is something people can’t wait to use! We all can’t wait to go back to a exclusive Microsoft world, using Windows, Office, the new Spartan browser – and creating documents, spreadsheets and even presentations using Office, with those hundreds of complex features (anyone know how to make a pivot table?) on our phones!

Just like those printing press manufacturers were sure people really wanted documents printed on presses, and couldn’t wait to unplug those Xerox machines and return to the old way of doing things. They just needed presses to have more features, more capabilities, more speed!

The best thing in Windows 10 is Cortana, which is a really cool, intelligent digital assistant. But, rather than making Cortana a tool developers can buy to integrate into their iOS or Android app the only way a developer can use Cortana is if they go into this exclusive Windows-only world. That’s a significant request.

Microsoft made this mistake before. Kinect was a great tool. But the only way to use it, initially, was on an xBox – and still is limited to Windows. Despite its many superb features, Kinect didn’t develop anywhere near its potential. Cortana now suffers from the same problem. Rather than offering the tool so it can find its best use and markets, Microsoft requires developers and consumers buy into the Windows-exclusive world if you want to use Cortana.

Microsoft hasn’t yet figured out that it lost relevance years ago when it missed the move to mobile, and then launched Windows 8 and Surface to markets that didn’t really want those products. Now the market has gone mobile, and the leader isn’t Microsoft. Microsoft has to find a way to be relevant to the millions of people using alternative products, and the Windows 10 vision, which excludes all those competing devices, simply isn’t it.

There was lots of neat geeky stuff shown. Surface tablets using Windows 10 with an xBox app can now do real gaming, which looks pretty cool and helps move Microsoft forward in mobile gaming. That may be a product that sets Sony’s Playstation and Nintendo’s Wii on their heels. But that’s gaming, and historically not where Microsoft makes any money (nor for that matter does Sony or Nintendo.)

There is a new interactive whiteboard that integrates Skype and Windows tablets for digital enhancement of brainstorming meetings. But it is unclear how a company uses it when most employees already have iPhones or Samsung S5s or Notes. And for the totally geeky there was a demo of a holographic headset. But when it comes to disruptive products like this success requires finding really interesting applications that otherwise cannot be completed, and then the initial customers who have a really desperate need for that application who will become devoted users.

Launching such disruptive products has long been the bane of Microsoft’s existence. Microsoft thinks in mass market terms, and selling to its base. Not developing breakthrough applications and finding niche markets to launch new uses. Nor has Microsoft created a developer community aligned with that kind of work. They have long been taught to simply continue to do things that defend and extend the traditional base of product uses and customers.

The really big miss for this meeting was understanding developer needs. Today developers have an enormous base of iOS and Android users to whom they can sell their products. Windows has less than 3% share in mobile devices. What developer would commit their resources to developing products for Windows 10, which has an installed base only in laptops and desktops? In other words, yesterday’s technology base? Especially when to obtain the biggest benefits of Windows 10 that developer has to find end use customers (companies or consumers) willing to commit 100% to Windows everywhere – even including their televisions, thermostats and other devices in our ever smarter buildings?

Windows 10 has a lot of cool features. But Microsoft made a big miss by listening to the wrong people. By assuming its installed base couldn’t wait for a Microsoft-exclusive solution, and by behaving as if the installed base of mobile devices either didn’t exist or didn’t matter, the company showed its hubris (once again.) If all it took to succeed were great products, the market would never have shifted from Macintosh computers to Windows machines in the 1990s. Microsoft simply doesn’t realize that it lacks the relevance to pull of its grand vision, and as such Windows 10 has almost no chance of stopping the Apple/Google/Samsung juggernaut.

by Adam Hartung | Dec 11, 2014 | Current Affairs, Defend & Extend, In the Whirlpool, Leadership, Lifecycle, Television, Web/Tech

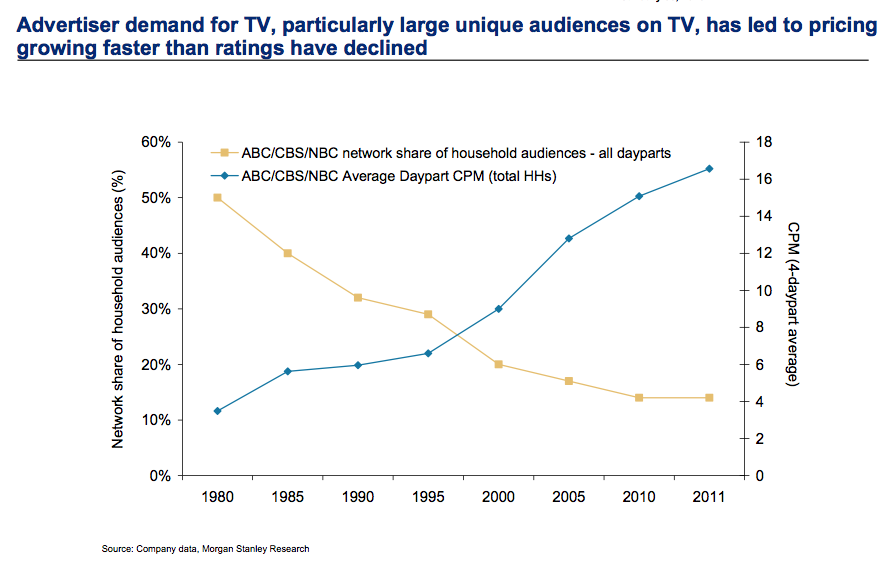

The trend toward the death of broadcast TV as we’ve known it keeps moving forward. This trend may not happen as fast as the death of desktop computers, but it is a lot faster than glacier melting.

This television season (through October) Magna Global has reported that even the oldest viewers (the TV Generation 55-64) watched 3% less TV. Those 35-54 watched 5% less. Gen Xers (25-34) watched 8% less, and Millenials (18-24) watched a whopping 14% less TV. Live sports viewing is not even able to maintain its TV audience, with NFL viewership across all networks down 10-19%.

Everyone knows what is happening. People are turning to downloaded entertainment, mostly on their mobile devices. With a trend this obvious, you’d think everyone in the media/TV and consumer goods industries would be rethinking strategy and retooling for a new future.

But, you would be wrong. Because despite the obviousness of the trend, emotional ties to hoping the old business sticks around are stronger than logic when it comes to forecasting.

CBS predicted at the beginning of 2014 TV ad revenue would grow 4%. Oops. Now CBS’s lead forecaster is admitting he was way off, and adjusted revenues were down 1% for the year. But, despite the trend in viewer behavior and ad expenditures in 2014, he now predicts a growth of 2% for 2015.

That, my young friends, is how “hockey stick” forecasts are created. A lot of old assumptions, combined with a willingness to hope trends will be delayed, and you can ignore real data while promising people that the future will indeed look like the past – even when it defies common sense.

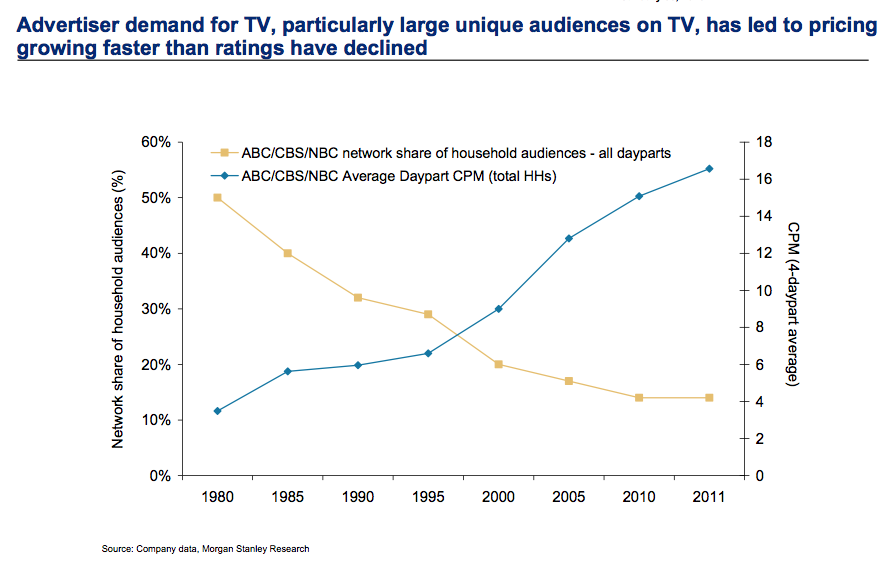

To compensate for fewer ads the networks have raised prices on all ads. But how long can that continue? This requires a really committed buyer (read more about CMO weaknesses below) who simply refuses to acknowledge the market has shifted and the dollars need to shift with it. That cannot last forever.

Meanwhile, us old folks can remember the days when Nielsen ratings determined what was programmed on TV, as well as what advertisers paid. Nielsen had a lock on measuring TV audience viewing, and wielded tremendous power in the media and CPG world.

But now AC Nielsen is struggling to remain relevant. With TV viewership down, time shifting of shows common and streaming growing like the proverbial weed Nielsen has no idea what entertainment the public watches. They don’t know what, nor when, nor where. Unwilling to move quickly to develop tools for catching all the second screen viewing, Nielsen has no plan for telling advertisers what the market really looks like – and the company looks to become a victim of changing markets.

Which then takes us to looking at those folks who actually buy ads that drive media companies. The Chief Marketing Officers (CMOs) of CPG companies. Surely these titans of industry are on top of these trends, and rapidly shifting their spending to catch the viewers with the most ads placed for the lowest cost.

You would wish.

Unfortunately, because these senior executives are in the oldest age groups, they are a victim of their own behavior. They still watch TV, so assume others must as well. If there is cyber-data saying they are wrong, well they simply discount that data. The Nielsen’s aren’t accurate, but these execs still watch the ratings “because it’s the best info we have” – a blatant untruth by the way. But Nielsen does conveniently reinforce their built in assumptions, and their hope that they won’t have to change their media spend plans any time soon.

Further, very few of these CMOs actually use social media. The vast majority watch their children, grandchildren and young employees use mobile devices constantly – and they bemoan all the activity on YouTube, Facebook, Instagram and Twitter – or for the most part even Linked-in. But they don’t actually USE these products. They don’t post information. They don’t set up and follow channels. They don’t connect with people, share information, exchange photos or tell stories on social media. Truthfully, they ignore these trends in their own lives. Which leaves them woefully inept at figuring out how to change their company marketing so it can be more relevant.

The trend is obvious. The answer, equally so. Any modern marketer should be an avid user of social media. Most network heads and media leaders are farther removed from social media than the Pope! They don’t constantly download entertainment, and exchanging with others on all the platforms. They can’t manage the use of these channels when they don’t have a clue how they work, or how other people use them, or understand why they are actually really valuable tools.

Are you using these modern tools? Are you actually living, breathing, participating in the trends? Or are you, like these outdated execs, biding your time wasting money on old programs while you look forward to retirement? And likely killing your company.

When trends emerge it is imperative we become part of that trend. You can’t simply observe it, because your biases will lead you to hope the trend reverts as you continue doing more of the same. A leader has to adopt the trend as a leader, be a practicing participant, and learn how that trend will make a substantial difference in the business. And then apply some vision to remain relevant and successful.

by Adam Hartung | Nov 28, 2014 | Current Affairs, Innovation, Leadership, Web/Tech

Last week I gave 1,000 VHS video tapes to Goodwill Industries. These had been accumulated through 30 years of home movie watching, including tapes purchased for entertaining my 3 children.

It was startling to realize how many of these I had bought, and also surprising to learn they were basically valueless. Not because the content was outdated, because many are still popular titles. But rather because today the content someone wants can be obtained from a streaming download off Amazon or Netflix more conveniently than dealing with these tapes and a mechanical media player.

It isn’t just a shift in technology that made those tapes obsolete. Rather, a major trend has shifted. We don’t really seek to “own” things any more. We’ve become a world of “renters.”

The choice between owning and renting has long been an option. We could rent video tapes, and DVDs. But even though we often did this, most Boomers also ended up buying lots of them. Boomers wanted to own things. Owning was almost always considered better than renting.

Boomers wanted to own their cars, and often more than one. Auto renting was only for business trips. Boomers wanted to own their houses, and often more than one. Why rent a summer home, when, if you could afford it, you could own one. Rent a boat? Wouldn’t it be better to own your own boat (even if you only use it 10 times/year?)

Now we think very, very differently. I haven’t watched a movie on any hard media in several years. When I find time for video entertainment, I simply download what I want, enjoy it and never think about it again. A movie library seems – well – unnecessary.

As a Boomer, there’s all those CDs, cassette tapes (yes, I have them) and even hundreds of vinyl records I own. Yet, I haven’t listened to any of them in years. It’s far easier to simply turn on Pandora or Spotify – or listen to a channel I’ve constructed on YouTube. I really don’t know why I continue to own those old media players, or the media.

Since the big real estate meltdown many people are finding home ownership to be not as good as renting. Why take such a huge risk, paying that mortgage, if you don’t have to?

That this is a trend is even clearer generationally. Younger people really don’t see the benefit of home ownership, not when it means taking on so much additional debt. Home ownership costs are so high that it means giving up a lot of other things. And what’s the benefit? Just to say you own your home?

Where Boomers couldn’t wait to own a car, young people are far less likely. Especially in, or near, urban areas. The cost of auto ownership, including maintenance, insurance and parking, becomes really expensive. Compared with renting a ZipCar for a few hours when you really need a car, ownership seems not only expensive, but a downright hassle.

And technology has followed this trend. Once we wanted to own a PC, and on that PC we wanted to own lots of data – including movies, pictures, books – anything that could be digitized. And we wanted to own software applications to capture, view, alter and display that data. The PC was something that fit the Boomer mindset of owning your technology.

But that is rapidly becoming superfluous. With a mobile device you can keep all your data in a cloud. Data you want to access regularly, or data you want to rent. There’s no reason to keep the data on your own hard drive when you can access it 24×7 everywhere with a mobile device.

And the same is true for acting on the data. Software as a service (SaaS) apps allow you to obtain a user license for $10-$20/user, or $.99, or sometimes free. Why spend $200 (or a lot more) for an application when you can accomplish your task by simply downloading a mobile app?

So I no longer want to own a VCR player (or DVD player for that matter) to clutter up my family room. And I no longer want to fill a closet with tapes or cased DVDs. Likewise, I no longer want to carry around a PC with all my data and applications. Instead, a small, easy to use mobile device will allow me to do almost everything I want.

It is this mega trend away from owning, and toward a simpler lifestyle, that will end the once enormous PC industry. When I can do all I really want to do on my connected device – and in fact often do more things because of those hundreds of thousands of apps – why would I accept the size, weight, complexity, failure problems and costs of the PC?

And, why would I want to own something like Microsoft Office? It is a huge set of applications which contain dozens (hundreds?) of functions I never use. Wouldn’t life be much simpler, easier and cheaper if I acquire the rights to use the functionality I need, when I need it?

There was a time I couldn’t imagine living without my media players, and those DVDs, CDs, tapes and records. But today, I’m giving lots of them away – basically for recycling. While we still use PCs for many things today, it is now easy to visualize a future where I use a PC about as often as I now use my DVD player.

In that world, what happens to Microsoft? Dell? Lenovo?

The implications of this are far-reaching for not only our personal lives, and personal technology suppliers, but for corporate IT. Once IT managed mainframes. Then server farms, networks and thousands of PCs. What will a company need an IT department to do if employees use their own mobile devices, across common networks, using apps that cost a few bucks and store files on secure clouds?

If corporate technology is reduced to just operating some “core” large functions like accounting, how big – or strategic – is IT? The “T” (technology) becomes irrelevant as people focus on gathering and analyzing information. But that’s not been the historical training for IT employees.

Further, if Salesforce.com showed us that even big corporations can manage something as critical as their customer information in a SaaS environment on mobile devices, is it not possible to imagine accounting and supply chain being handled the same way? If so, what role will IT have at all?

The trend toward renting rather than owning is monumental. It affects every business. But in an ironic twist of fate, it may dramatically reduce the focus on IT that has been so critical for the Boomer generation.

by Adam Hartung | Nov 3, 2014 | Current Affairs, In the Rapids, Leadership, Web/Tech

On April 15 Zebra Technologies announced its planned acquisition of Motorola’s Enterprise Device Business. This was remarkable because it represented a major strategic shift for Zebra, and one that would take a massive investment in products and technologies which were wholly new to the company. A gutsy play to make Zebra more relevant in its B-2-B business as interest in its “core” bar code business was declining due to generic competition.

Last week the acquisition was completed. In an example of Jonah swallowing the whale, Zebra added $2.5B to annual revenues on its old base of $1B (2.5x incremental revenue,) an additional 4,500 employees joined its staff of 2,500 and 69 new facilities were added. Gulp.

As CEO Anders Gustafsson told me, “after the deal was agreed to I felt like the dog that caught the car. ”

Fortunately Zebra has a plan, and it is all around growth. Acquisitions led by private equity firms, hedge funds or leveraged buyout partners are usually quick to describe the “synergies” planned for after the acquisition. Synergy is a code word for massive cost cutting (usually meaning large layoffs,) selling off assets (from buildings to product lines and intellectual property rights) and shutting down what the buyers call “marginal” businesses. This always makes the company smaller, weaker and less likely to survive as the new investors focus on pulling out cash and selling the remnants to some large corporation.

There is no growth plan.

But Zebra has publicly announced that after this $3.25B investment they plan only $150M of savings over 2 years. Which means Zebra’s management team intends to grow what they bought, not decimate it. What a novel, or perhaps throwback, idea.

Minimal cost cutting reflects a deal, as CEO Gustafsson told me, “envisioned by management, not by bankers.”

Zebra’s management knew the company was frequently pitching for new work in partnership with Motorola. The two weren’t competitors, but rather two companies working to move their clients forward. But in a disorganized, unplanned way because they were two totally different companies. Zebra’s team recognized that if this became one unit, better planning for clients, the products could work better together, the solutions more directly target customer needs and it would be possible to slingshot forward ahead of competitors to grow revenues.

As CEO since 2007, Anders Gustafsson had pushed a strategy which could grow Zebra, and move the company outside its historical core business of bar code printers and readers. The leadership considered buying Symbol Technology, but wasn’t ready and watched it go to Motorola.

Then Zebra’s team knuckled down on their strategy work. CEO Gustafsson spelled out for me the 3 trends which were identified to build upon:

- Mobility would continue to be a secular growth trend. And business customers needed products with capabilities beyond the generic smart phone. For example, the kind of integrated data entry and printing device used at a remote rental car return. These devices drive business productivity, and customers hunger for such solutions.

- From the days of RFID, where Zebra was an early player, had emerged automatic data capture – which became what now is commonly called “The Internet of Things” – and this trend too had far to extend. By connecting the physical and digital worlds, in markets like retail inventory management, big productivity boosts were possible in formerly moribund work that added cost but little value.

- Cloud-based (SaaS and growth of lightweight apps) ecosystems were going to provide fast growth environments. Client need for capability at the employee’s (or their customer’s) fingertips would grow, and those people (think distributors, value added resellers [VARs]) who build solutions will create apps, accessible via the cloud, to rapidly drive customer productivity.

With this groundwork, the management team developed future scenarios in which it became increasingly clear the value in merging together with Motorola devices to accelerate growth. According to CEO Gustafsson, “it would bring more digital voice to the Zebra physical voice. It would allow for more complete product offerings which would fulfill critical, macro customer trends.”

But, to pull this off required selling the Board of Directors. They are ultimately responsible for company investments, and this was – as described above – a “whopper.”

The CEO’s team spent a lot of time refining the message, to be clear about the benefits of this transaction. Rather than pitching the idea to the Board, they offered it as an opportunity to accelerate strategy implementation. Expecting a wide range of reactions, they were not surprised when some Directors thought this was “phenomenal” while others thought it was “fraught with risk.”

So management agreed to work with the Board to undertake a thorough due diligence process, over many weeks (or months it turned out) to ask all the questions. A key executive, who was a bit skeptical in her own right, took on the role of the “black hat” leader. Her job was to challenge the many ideas offered, and to be a chronic skeptic; to not let the team become enraptured with the idea and thereby sell themselves on success too early, and/or not consider risks thoroughly enough. By persistently undertaking analysis, education led the Board to agree that management’s strategy had merit, and this deal would be a breakout for Zebra.

Next came completing financing. This was a big deal. And the only way to make it happen was for Zebra to take on far more debt than ever in the company’s history. But, the good news was that interest rates are at record low levels, so the cost was manageable.

Zebra’s leadership patiently met with bankers and investors to overview the market strategy, the future scenarios and their plans for the new company. They over and again demonstrated the soundness of their strategy, and the cash flow ability to service the debt. Zebra had been a smaller, stable company. The debt added more dynamism, as did the much greater revenues. The requirement was to decide if the strategy was soundly based on trends, and had a high likelihood of success. Quickly enough, the large shareholders agreed with the path forward, and the financing was fully committed.

Now that the acquisition is complete we will all watch carefully to see if the growth machine this leadership team created brings to market the solutions customers want, so Zebra can generate the revenue and profits investors want. If it does, it will be a big win for not only investors but Zebra’s employees, suppliers and the communities in which Zebra operates.

The obvious question has to be, why didn’t Motorola do this deal? After all, they were the whale. It would have been much easier for people to understand Motorola buying Zebra than the gutsy deal which ultimately happened.

Answering this question requires a lot more thought about history. In 2006 Motorola had launched the Razr phone and was an industry darling. Newly minted CEO Ed Zander started partnering with Google and Apple rather than developing proprietary solutions like Razr. Carl Icahn soon showed up as an activist investor intent on restructuring the company and pulling out more cash. Quickly then-CEO Ed Zander was pushed out the door. New leadership came in, and Motorola’s new product introductions disappeared.

Under pressure from Mr. Icahn, Motorola started shrinking under direction of the new CEO. R&D and product development went through many cuts. New product launches simply were delayed, and died. The cellular phone business began losing money as RIM brought to market Blackberry and stole the enterprise show. Year after year the focus was on how to raise cash at Motorola, not how to grow.

After 4 years, Mr. Icahn was losing money on his position in Motorola. A year later Motorola spun out the phone business, and a year after that leadership paid Mr. Icahn $1.2B in a stock repurchase that saved him from losses. The CEO called this buyout of Icahn the “end of a journey” as Mr. Icahn took the money and ran. How this benefited Motorola is – let’s say unclear.

But left in Icahn’s wake was a culture of cut and shred, rather than invest. After 90 years of invention, from Army 2-way radios to police radios, from AM car radios to home televisions, the inventor analog and digital cell towers and phones, there was no more innovation at Motorola. Motorola had become a company where the leaders, and Board, only thought about how to raise cash – not deploy it effectively within the corporation. There was very little talk about how to create new markets, but plenty about how to retrench to ever smaller “core” markets with no sales growth and declining margins. In September of this year long-term CEO Greg Brown showed no insight for what the company can become, but offered plenty of thoughts on defending tax inversions and took the mantle as apologist for CEOs who use financial machinations to confuse investors.

Investors today should cheer the leadership, in management and on the Board, at Zebra. Rather than thinking small, they thought big. Rather than bragging about their past, they figured out what future they could create. Rather than looking at their limits, they looked at the possibilities. Rather than giving up in the face of objections, they studied the challenges until they had answers. Rather than remaining stuck in their old status quo, they found the courage to become something new.

Bravo.

by Adam Hartung | Oct 6, 2014 | Current Affairs, In the Swamp, In the Whirlpool, Leadership, Web/Tech

Hewlett Packard is splitting in two. Do you find yourself wondering why? You aren’t alone.

Hewlett Packard is nearly 75 years old. One of the original “silicone valley companies,” it started making equipment for engineers and electronic technicians long before computers were every day products. Over time HP’s addition of products like engineering calculators moved it toward more consumer products. And eventually HP became a dominant player in printers. All of these products were born out of deep skills in R&D, engineering and product development. HP had advantages because its products were highly desirable and unique, which made it nicely profitable.

But along came a CEO named Carly Fiorina, and she decided HP needed to grow much bigger, much more quickly. So she bought Compaq, which itself had bought Digital Equipment, so HP could sell Wintel PCs. PCs were a product in which HP had no advantage. PC production had always been an assembly operation of other companies’ intellectual property. It had been a very low margin, brutally difficult place to grow unless one focused on cost lowering rather than developing intellectual capital. It had nothing in common with HP’s business.

To fight this new margin battle HP replaced Ms. Fiorina with Mark Hurd, who recognized the issues in PC manufacturing and proceeded to gut R&D, product development and almost every other function in order to push HP into a lower cost structure so it could compete with Dell, Acer and other companies that had no R&D and cultures based on cost controls. This led to internal culture conflicts, much organizational angst and eventually the ousting of Mr. Hurd.

But, by that time HP was a company adrift with no clear business model to help it have a sustainably profitable future.

Now HP is 4 years into its 5 year turnaround plan under Meg Whitman’s leadership. This plan has made HP much smaller, as layoffs have dominated the implementation. It has weakened the HP brand as no important new products have been launched, and the gutted product development capability is still no closer to being re-established. And PC sales have stagnated as mobile devices have taken center stage – with HP notably weak in mobile products. The company has drifted, getting no better and showing no signs of re-developing its historical strengths.

So now HP will split into two different companies. Following the old adage “if you can’t dazzle ’em with brilliance, baffle ’em with bulls**t.” When all else fails, and you don’t know how to actually lead a company, then split it into pieces, push off the parts to others to manage and keep at least one CEO role for yourself.

Let’s not forget how this mess was created. It was a former CEO who decided to expand the company into an entirely different and lower margin business where the company had no advantage and the wrong business model. And another that destroyed long-term strengths in innovation to increase short-term margins in a generic competition. And then yet a third who could not find any solution to sustainability while pushing through successive rounds of lay-offs.

This was all value destruction created by the persons at the top. “Strategic” decisions made which, inevitably, hurt the organization more than helped it. Poorly thought through actions which have had long-term deleterious repercussions for employees, suppliers, investors and the communities in which the businesses operate.

The game of musical chairs has been very good for the CEOs who controlled the music. They were paid well, and received golden handshakes. They, and their closest reports, did just fine. But everyone else….. well…..