by Adam Hartung | May 15, 2016 | In the Swamp, Investing, real estate, Retail

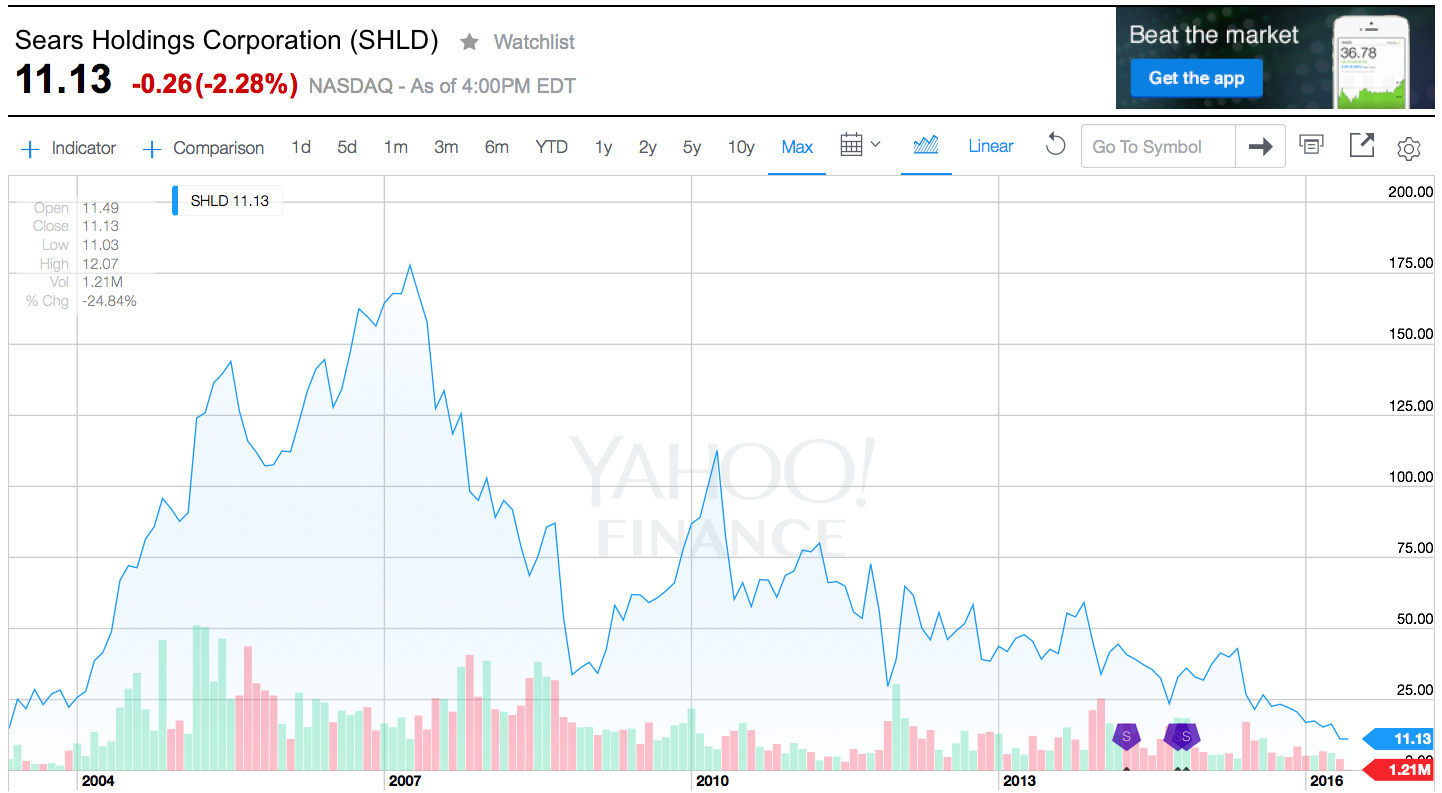

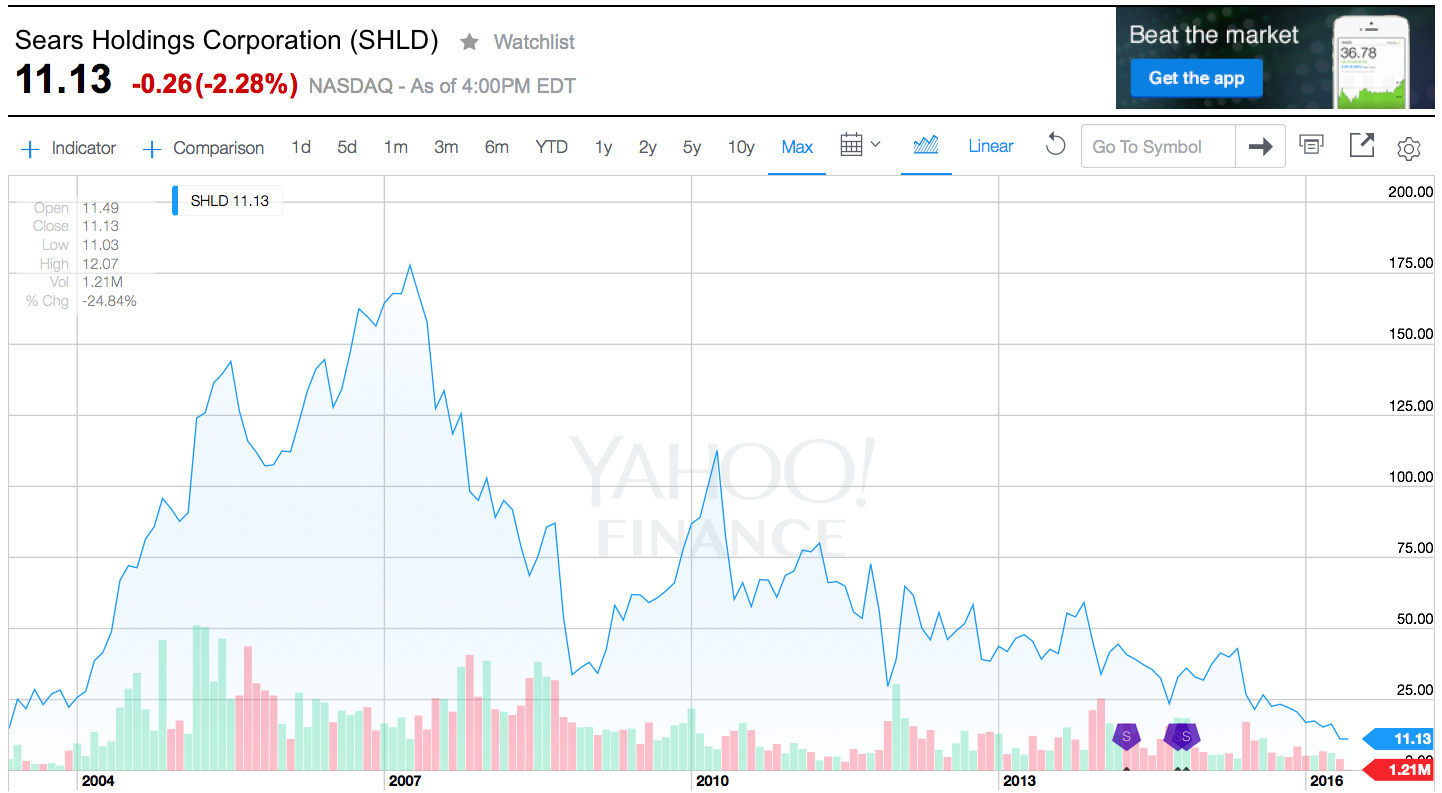

Last week Sears announced sales and earnings. And once again, the news was all bad. The stock closed at a record, all time low. One chart pretty much sums up the story, as investors are now realizing bankruptcy is the most likely outcome.

Chart Source: Yahoo Finance 5/13/16

Quick Rundown: In January, 2002 Kmart is headed for bankruptcy. Ed Lampert, CEO of hedge fund ESL, starts buying the bonds. He takes control of the company, makes himself Chairman, and rapidly moves through proceedings. On May 1, 2003, KMart begins trading again. The shares trade for just under $15 (for this column all prices are adjusted for any equity transactions, as reflected in the chart.)

Lampert quickly starts hacking away costs and closing stores. Revenues tumble, but so do costs, and earnings rise. By November, 2004 the stock has risen to $90. Lampert owns 53% of Kmart, and 15% of Sears. Lampert hires a new CEO for Kmart, and quickly announces his intention to buy all of slow growing, financially troubled Sears.

In March, 2005 Sears shareholders approve the deal. The stock trades for $126. Analysts praise the deal, saying Lampert has “the Midas touch” for cutting costs. Pumped by most analysts, and none moreso than Jim Cramer of “Mad Money” fame (Lampert’s former roommate,) in 2 years the stock soars to $178 by April, 2007. So far Lampert has done nothing to create value but relentlessly cut costs via massive layoffs, big inventory reductions, delayed payments to suppliers and store closures.

Homebuilding falls off a cliff as real estate values tumble, and the Great Recession begins. Retailers are creamed by investors, and appliance sales dependent Sears crashes to $33.76 in 18 months. On hopes that a recovering economy will raise all boats, the stock recovers over the next 18 months to $113 by April, 2010. But sales per store keep declining, even as the number of stores shrinks. Revenues fall faster than costs, and the stock falls to $43.73 by January, 2013 when Lampert appoints himself CEO. In just under 2.5 years with Lampert as CEO and Chairman the company’s sales keep falling, more stores are closed or sold, and the stock finds an all-time low of $11.13 – 25% lower than when Lampert took KMart public almost exactly 13 years ago – and 94% off its highs.

What happened?

Sears became a retailing juggernaut via innovation. When general stores were small and often far between, and stocking inventory was precious, Sears invented mail order catalogues. Over time almost every home in America was receiving 1, or several, catalogues every year. They were a major source of purchases, especially by people living in non-urban communities. Then Sears realized it could open massive stores to sell all those things in its catalogue, and the company pioneered very large, well stocked stores where customers could buy everything from clothes to tools to appliances to guns. As malls came along, Sears was again a pioneer “anchoring” many malls and obtaining lower cost space due to the company’s ability to draw in customers for other retailers.

To help customers buy more Sears created customer installment loans. If a young couple couldn’t afford a stove for their new home they could buy it on terms, paying $10 or $15 a month, long before credit cards existed. The more people bought on their revolving credit line, and the more they paid Sears, the more Sears increased their credit limit. Sears was the “go to” place for cash strapped consumers. (Eventually, this became what we now call the Discover card.)

In 1930 Sears expanded the Allstate tire line to include selling auto insurance – and consumers could not only maintain their car at Sears they could insure it as well. As its customers grew older and more wealthy, many needed help with financia advice so in 1981 Sears bought Dean Witter and made it possible for customers to figure out a retirement plan while waiting for their tires to be replaced and their car insurance to update.

To put it mildly, Sears was the most innovative retailer of all time. Until the internet came along. Focused on its big stores, and its breadth of products and services, Sears kept trying to sell more stuff through those stores, and to those same customers. Internet retailing seemed insignificantly small, and unappealing. Heck, leadership had discontinued the famous catalogues in 1993 to stop store cannibalization and push people into locations where the company could promote more products and services. Focusing on its core customers shopping in its core retail locations, Sears leadership simply ignored upstarts like Amazon.com and figured its old success formula would last forever.

But they were wrong. The traditional Sears market was niched up across big box retailers like Best Buy, clothiers like Kohls, tool stores like Home Depot, parts retailers like AutoZone, and soft goods stores like Bed, Bath & Beyond. The original need for “one stop shopping” had been overtaken by specialty retailers with wider selection, and often better pricing. And customers now had credit cards that worked in all stores. Meanwhile, for those who wanted to shop for many things from home the internet had taken over where the catalogue once began. Leaving Sears’ market “hollowed out.” While KMart was simply overwhelmed by the vast expansion of WalMart.

What should Lampert have done?

There was no way a cost cutting strategy would save KMart or Sears. All the trends were going against the company. Sears was destined to keep losing customers, and sales, unless it moved onto trends. Lampert needed to innovate. He needed to rapidly adopt the trends. Instead, he kept cutting costs. But revenues fell even faster, and the result was huge paper losses and an outpouring of cash.

To gain more insight, take a look at Jeff Bezos. But rather than harp on Amazon.com’s growth, look instead at the leadership he has provided to The Washington Post since acquiring it just over 2 years ago. Mr. Bezos did not try to be a better newspaper operator. He didn’t involve himself in editorial decisions. Nor did he focus on how to drive more subscriptions, or sell more advertising to traditional customers. None of those initiatives had helped any newspaper the last decade, and they wouldn’t help The Washington Post to become a more relevant, viable and profitable company. Newspapers are a dying business, and Bezos could not change that fact.

Mr. Bezos focused on trends, and what was needed to make The Washington Post grow. Media is under change, and that change is being created by technology. Streaming content, live content, user generated content, 24×7 content posting (vs. deadlines,) user response tracking, readers interactivity, social media connectivity, mobile access and mobile content — these are the trends impacting media today. So that was where he had leadership focus. The Washington Post had to transition from a “newspaper” company to a “media and technology company.”

So Mr. Bezos pushed for hiring more engineers – a lot more engineers – to build apps and tools for readers to interact with the company. And the use of modern media tools like headline testing. As a result, in October, 2015 The Washington Post had more unique web visitors than the vaunted New York Times. And its lead is growing. And while other newspapers are cutting staff, or going out of business, the Post is adding writers, editors and engineers. In a declining newspaper market The Washington Post is growing because it is using trends to transform itself into a company readers (and advertisers) value.

CEO Lampert could have chosen to transform Sears Holdings. But he did not. He became a very, very active “hands on” manager. He micro-managed costs, with no sense of important trends in retail. He kept trying to take cash out, when he needed to invest in transformation. He should have sold the real estate very early, sensing that retail was moving on-line. He should have sold outdated brands under intense competitive pressure, such as Kenmore, to a segment supplier like Best Buy. He then should have invested that money in technology. Sears should have been a leader in shopping apps, supplier storefronts, and direct-to-customer distribution. Focused entirely on defending Sears’ core, Lampert missed the market shift and destroyed all the value which initially existed in the great retail merger he created.

Impact?

Every company must understand critical trends, and how they will apply to their business. Nobody can hope to succeed by just protecting the core business, as it can be made obsolete very, very quickly. And nobody can hope to change a trend. It is more important than ever that organizations spend far less time focused on what they did, and spend a lot more time thinking about what they need to do next. Planning needs to shift from deep numerical analysis of the past, and a lot more in-depth discussion about technology trends and how they will impact their business in the next 1, 3 and 5 years.

Sears Holdings was a 13 year ride. Investor hope that Lampert could cut costs enough to make Sears and KMart profitable again drove the stock very high. But the reality that this strategy was impossible finally drove the value lower than when the journey started. The debacle has ruined 2 companies, thousands of employees’ careers, many shopping mall operators, many suppliers, many communities, and since 2007 thousands of investor’s gains. Four years up, then 9 years down. It happened a lot faster than anyone would have imagined in 2003 or 2004. But it did.

And it could happen to you. Invert your strategic planning time. Spend 80% on trends and scenario planning, and 20% on historical analysis. It might save your business.

by Adam Hartung | Apr 22, 2013 | Current Affairs, Defend & Extend, In the Swamp, In the Whirlpool, Leadership

JCPenney's board fired the company CEO 18 months ago. Frustrated with weak performance, they replaced him with the most famous person in retail at the time. Ron Johnson was running Apple's stores, which had the highest profit per square foot of any retail chain in America. Sure he would bring the Midas touch to JC Penney they gave him a $50M sign-on bonus and complete latitude to do as he wished.

Things didn't work out so well. Sales fell some 25%. The stock dropped 50%. So about 2 weeks ago the Board fired Ron Johnson.

The first mistake: Ron Johnson didn't try solving the real problem at JC Penney. He spent lavishly trying to remake the brand. He modernized the logo, upped the TV ad spend, spruced up stores and implemented a more consistent pricing strategy. But that all was designed to help JC Penney compete in traditional brick-and-mortar retail. Against traditional companies like Wal-Mart, Kohl's, Sears, etc. But that wasn't (and isn't) JC Penney's problem.

The problem in all of traditional retail is the growth of on-line. In a small margin business with high fixed costs, like traditional retail, even a small revenue loss has a big impact on net profit. For every 5% revenue decline 50-90% of that lost cash comes directly off the bottom line – because costs don't fall with revenues. And these days every quarter – every month – more and more customers are buying more and more stuff from Amazon.com and its on-line brethren rather than brick and mortar stores. It is these lost revenues that are destroying revenues and profits at Sears and JC Penney, and stagnating nearly everyone else including Wal-Mart.

Coming from the tech world, you would have expected CEO Johnson to recognize this problem and radically change the strategy, rather than messing with tactics. He should have looked to close stores to lower fixed costs, developed a powerful on-line presence and marketed hard to grab more customers showrooming or shopping from home. He should have targeted to grow JCP on-line, stealing revenues from other traditional retailers, while making the company more of a hybrid retailer that profitably met customer needs in stores, or on-line, as suits them. He should have used on-line retail to take customers from locked-in competitors unable to deal with "cannibalization."

No wonder the results tanked, and CEO Johnson was fired. Doing more of the tired, old strategies in a shifting market never works. In Apple parlance, he needed to be focused on an iPad strategy, when instead he kept trying to sell more Macs.

But now the Board has made its second mistake. Bringing back the old CEO, Myron Ullman, has deepened JP Penney's lock-in to that old, traditional and uncompetitve brick-and-mortar strategy. He intends to return to JCP's legacy, buy more newspaper coupons, and keep doing more of the same. While hoping for a better outcome.

What was that old description of insanity? Something about repeating yourself…..

Expectedly, Penney's stock dropped another 10% after announcing the old CEO would return. Investors are smart enough to recognize the retail market has shifted. That newsapaper coupons, circulars and traditional advertising is not enough to compete with on-line merchants which have lower fixed costs, faster inventory turns and wider product selection.

It certainly appears Mr. Johnson was not the right person to grow JC Penney. All the more reason JCP needs to accelerate its strategy toward the on-line retail trend. Going backward will only worsen an already terrible situation.

by Adam Hartung | Oct 12, 2011 | Current Affairs, Defend & Extend, eBooks, In the Rapids, In the Whirlpool, Innovation, Leadership, Lifecycle, Lock-in, Transparency, Web/Tech

Wal-Mart has had 9 consecutive quarters of declining same-store sales (Reuters.) Now that’s a serious growth stall, which should worry all investors. Unfortunately, the odds are almost non-existent that the company will reverse its situation, and like Montgomery Wards, KMart and Sears is already well on the way to retail oblivion. Faster than most people think.

After 4 decades of defending and extending its success formula, Wal-Mart is in a gladiator war against a slew of competitors. Not just Target, that is almost as low price and has better merchandise. Wal-Mart’s monolithic strategy has been an easy to identify bulls-eye, taking a lot of shots. Dollar General and Family Dollar have gone after the really low-priced shopper for general merchandise. Aldi beats Wal-Mart hands-down in groceries. Category killers like PetSmart and Best Buy offer wider merchandise selection and comparable (or lower) prices. And companies like Kohl’s and J.C. Penney offer more fashionable goods at just slightly higher prices. On all fronts, traditional retailers are chiseling away at Wal-Mart’s #1 position – and at its margins!

Yet, the company has eschewed all opportunities to shift with the market. It’s primary growth projects are designed to do more of the same, such as opening smaller stores with the same strategy in the northeast (Boston.com). Or trying to lure customers into existing stores by showing low-price deals in nearby stores on Facebook (Chicago Tribune) – sort of a Facebook as local newspaper approach to advertising. None of these extensions of the old strategy makes Wal-Mart more competitive – as shown by the last 9 quarters.

On top of this, the retail market is shifting pretty dramatically. The big trend isn’t the growth of discount retailing, which Wal-Mart rode to its great success. Now the trend is toward on-line shopping. MediaPost.com reports results from a Kanter Retail survey of shoppers the accelerating trend:

- In 2010, preparing for the holiday shopping season, 60% of shoppers planned going to Wal-Mart, 45% to Target, 40% on-line

- Today, 52% plan to go to Wal-Mart, 40% to Target and 45% on-line.

This trend has been emerging for over a decade. The “retail revolution” was reported on at the Harvard Business School website, where the case was made that traditional brick-and-mortar retail is considerably overbuilt. And that problem is worsening as the trend on-line keeps shrinking the traditional market. Several retailers are expected to fail. Entire categories of stores. As an executive from retailer REI told me recently, that chain increasingly struggles with customers using its outlets to look at merchandise, fit themselves with ideal sizes and equipment, then buying on-line where pricing is lower, options more plentiful and returns easier!

While Wal-Mart is huge, and won’t die overnight, as sure as the dinosaurs failed when the earth’s weather shifted, Wal-Mart cannot grow or increase investor returns in an intensely competitive and shifting retail environment.

The winners will be on-line retailers, who like David versus Goliath use techology to change the competition. And the clear winner at this, so far, is the one who’s identified trends and invested heavily to bring customers what they want while changing the battlefield. Increasingly it is obvious that Amazon has the leadership and organizational structure to follow trends creating growth:

- Amazon moved fairly quickly from a retailer of out-of-inventory books into best-sellers, rapidly dominating book sales bankrupting thousands of independents and retailers like B.Dalton and Borders.

- Amazon expanded into general merchandise, offering thousands of products to expand its revenues to site visitors.

- Amazon developed an on-line storefront easily usable by any retailer, allowing Amazon to expand its offerings by millions of line items without increasing inventory (and allowing many small retailers to move onto the on-line trend.)

- Amazon created an easy-to-use application for authors so they could self-publish books for print-on-demand and sell via Amazon when no other retailer would take their product.

- Amazon recognized the mobile movement early and developed a mobile interface rather than relying on its web interface for on-line customers, improving usability and expanding sales.

- Amazon built on the mobility trend when its suppliers, publishers, didn’t respond by creating Kindle – which has revolutionized book sales.

- Amazon recently launched an inexpensive, easy to use tablet (Kindle Fire) allowing customers to purchase products from Amazon while mobile. MediaPost.com called it the “Wal-Mart Slayer“

Each of these actions were directly related to identifying trends and offering new solutions. Because it did not try to remain tightly focused on its original success formula, Amazon has grown terrifically, even in the recent slow/no growth economy. Just look at sales of Kindle books:

Source: BusinessInsider.com

Unlike Wal-Mart customers, Amazon’s keep growing at double digit rates. In Q3 unique visitors rose 19% versus 2010, and September had a 26% increase. Kindle Fire sales were 100,000 first day, and 250,000 first 5 days, compared to 80,000 per day unit sales for iPad2. Kindle Fire sales are expected to reach 15million over the next 24 months, expanding the Amazon reach and easily accessible customers.

While GroupOn is the big leader in daily coupon deals, and Living Social is #2, Amazon is #3 and growing at triple digit rates as it explores this new marketplace with its embedded user base. Despite only a few month’s experience, Amazon is bigger than Google Offers, and is growing at least 20% faster.

After 1980 investors used to say that General Motors might not be run well, but it would never go broke. It was considered a safe investment. In hindsight we know management burned through company resources trying to unsuccessfully defend its old business model. Wal-Mart is an identical story, only it won’t have 3 decades of slow decline. The gladiators are whacking away at it every month, while the real winner is simply changing competition in a way that is rapidly making Wal-Mart obsolete.

Given that gladiators, at best, end up bloody – and most often dead – investing in one is not a good approach to wealth creation. However, investing in those who find ways to compete indirectly, and change the battlefield (like Apple,) make enormous returns for investors. Amazon today is a really good opportunity.

by Adam Hartung | May 10, 2011 | Current Affairs, In the Whirlpool, Innovation, Leadership, Lifecycle

Sears is threatening to move its headquarters out of the Chicago area. It’s been in Chicago since the 1880s. Now the company Chairman is threatening to move its headquarters to another state, in order to find lower operating costs and lower taxes.

Predictably “Officals Scrambling to Keep Sears in Illinois” is the Chicago Tribune headlined. That is stupid. Let Sears go. Giving Sears subsidies would be tantamount to putting a 95 year old alcoholic, smoking paraplegic at the top of the heart/lung transplant list! When it comes to subsidies, triage is the most important thing to keep in mind. And honestly, Sears ain’t worth trying to save (even if subsidies could potentially do it!)

“Fast Eddie Lampert” was the hedge fund manager who created Sears Holdings by using his takeover of bankrupt KMart to acquire the former Sears in 2003. Although he was nothing more than a financier and arbitrager, Mr. Lampert claimed he was a retailing genius, having “turned around” Auto Zone. And he promised to turn around the ailing Sears. In his corner he had the modern “Mad Money” screaming investor advocate, Jim Cramer, who endorsed Mr. Lampert because…… the two were once in college togehter. Mr. Cramer promised investors would do well, because he was simply sure Mr. Lampert was smart. Even if he didn’t have a plan for fixing the company.

Sears had once been a retailing goliath, the originator of home shopping with the famous Sears catalogue, and a pioneer in financing purchases. At one time you could obtain all your insurance, banking and brokerage needs at a Sears, while buying clothes, tools and appliances. An innovator, Sears for many years was part of the Dow Jones Industrial Average. But the world had shifted, Home Depot displaced Sears on the DJIA, and the company’s profits and revenues sagged as competitors picked apart the product lines and locations.

Simultaneously KMart had been destroyed by the faster moving and more aggressive Wal-Mart. Wal-Mart’s cost were lower, and its prices lower. Even though KMart had pioneered discount retailing, it could not compete with the fast growing, low cost Wal-Mart. When its bonds were worth pennies, Mr. Lampert bought them and took over the money-losing company.

By combining two losers, Mr. Lampert promised he would make a winner. How, nobody knew. There was no plan to change either chain. Just a claim that both were “great brands” that had within them other “great brands” like Martha Stewart (started before she was convicted and sent to jail), Craftsman and Kenmore. And there was a lot of real estate. Somehow, all those assets simlply had to be worth more than the market value. At least that’s what Mr. Lampert said, and people were ready to believe. And if they had doubts, they could listen to Jim Cramer during his daily Howard Beale impersonation.

Only they all were wrong.

Retailing had shifted. Smarter competitors were everywhere. Wal-Mart, Target, Dollar General, Home Depot, Best Buy, Kohl’s, JCPenney, Harbor Freight Tools, Amazon.com and a plethora of other compeltitors had changed the retail market forever. Likewise, manufacturers in apparel, appliances and tools had brough forward better products at better prices. And financing was now readily available from credit card companies.

Surely the real estate would be worth a fortune everyone thought. After all, there was so much of it. And there would never be too much retail space. And real estate never went down in value. At least, that’s what everyone said.

But they were wrong. Real estate was at historic highs compared to income, and ability to pay. Real estate was about to crater. And hardest hit in the commercial market was retail space, as the “great recession” wiped out home values, killed personal credit lines, and wiped out disposable income. Additionally, consumers increasingly were buying on-line instead of trudging off to stores fueling growth at Amazon and its peers rather than Sears – which had no on-line presence.

Those who were optimistic for Sears were looking backward. What had once been valuable they felt surely must be valuable again. But those looking forward could see that market shifts had rendered both KMart and Sears obsolete. They were uncompetitive in an increasingly more competitive marketplace. As competitors kept working harder, doing more, better, faster and cheaper Sears was not even in the game. The merger only made the likelihood of failure greater, because it made the scale fo change even greater.

The results since 2003 have been abysmal. Sales per store, a key retail benchmark, have declined every quarter since Mr. Lampert took over. In an effort to prove his financial acumen, Mr. Lampert led the charge for lower costs. And slash his management team did – cutting jobs at stores, in merchandising and everywhere. Stores were closed every quarter in an effort to keep cutting costs. All Mr. Lampert discussed were earnings, which he kept trying to keep from disintegrating. But with every quarter Sears has become smaller, and smaller. Now, Crains Chicago Business headlined, even the (in)famous chairman has to admit his past failure “Sears Chief Lampert: We Ought to be Doing a Lot Better.”

Sears once built, and owned, America’s tallest structure. But long ago Sears left the Sears Tower. Now it’s called the Willis Tower by the way – there is no Sears Tower any longer. Sears headquarters are offices in suburban Hoffman Estates, and are half empty. Eighty percent of the apparel merchandisers were let go in a recent move, taking that group to California where the outcome has been no better. Constant cost cutting does that. Makes you smaller, and less viable.

And now Sears is, well….. who cares? Do you even know where the closest Sears or Kmart store is to you? Do you know what they sell? Do you know the comparative prices? Do you know what products they carry? Do you know if they have any unique products, or value proposition? Do you know anyone who works at Sears? Or shops there? If the store nearest you closed, would you miss it amidst the Home Depot, Kohl’s or Best Buy competitors? If all Sears stores closed – every single location – would you care?

And now Illinois is considering giving this company subsidies to keep the headquarters here?

Here’s an alternative idea. Using whatever logic the state leaders can develop, using whatever dream scenario and whatever desperation economics they have in mind to save a handful of jobs, figure out what the subsidy might be. Then invest it in Groupon. Groupon is currently the most famous technology start-up in Illinois. Over the next 10 years the Groupon investment just might create a few thousand jobs, and return a nice bit of loot to the state treasury. The Sears money will be gone, and Sears is going to disappear anyway. Really, if you want to give a subsidy, if you want to “double down,” why not bet on a winner?

It really doesn’t have to be Groupon. The state residents will be much better off if the money goes into any business that is growing. Investing in the dying horse simply makes no sense. Beg Amazon, Google or Apple to open a center in Illinois – give them the building for free if you must. At least those will be jobs that won’t disappear. Or invest the money into venture funds that can invest in the next biotech or other company that might become a Groupon. Invest in senior design projects from engineering students at the University of Illinois in Chicago or Urbana/Champaign. Invest in the fillies that have a chance of winning the race!

Sentimenatality isn’t bad. We all deserve the right to “remember the good old days.” But don’t invest your retirement fund, or state tax receipts, in sentimentality. That’s how you end up like Detroit. Instead put that money into things that will grow. So you can be more like silicon valley. Invest in businesses that take advantage of market shifts, and leverage big trends to grow. Let go of sentimentality. And let go of Sears. Before it makes you bankrupt!

by Adam Hartung | Mar 30, 2011 | Current Affairs, In the Swamp, Innovation, Leadership

Summary:

- Too many leaders spend too much effort minimizing uncertainty

- Stock buybacks reflect fear of uncertainty, but are a losing investment

- Good performing organizations invest in new markets, products and services

- Success comes from not only investing, but in learning quickly what works (or doesn’t) and rapidly adapting

“If you don’t ever do anything, you can never screw up” my boss said.

I was 20 years old working in the blazing Oklahoma July sun at a grain elevator. I had asked the maintenance lead to modify a tool, thinking I could work faster. Unfortunately, my idea failed and my production started lagging. Offload production was slowing. I had to ask that the tool be put back to original condition, and I apologized to the elevator manager for my mistake.

That’s when he used my opening line, and went on to say “Don’t ever quit trying to do better. You’re a clever kid. Sometimes ideas work, sometimes they don’t, but if we dont’ try them we’ll never know. That’s why I agreed to your idea originally. I’ll accept a few well-intentioned ‘mistakes’ as long as you learn from them. Now go back to work and try to make up that production before end of day.”

Far too few leaders today give, or follow, such advice. The Economist recently waxed eloquently about how much today’s leaders dislike any kind of uncertainty (see “From Tsunami’s to Typhoons“). Most very consciously make decisions intended to reduce uncertainty – regardless of the impact on results! Rather than take advantage of events and trends, doing something new and different, they intentionally downplay market changes and diligently seek ways to make it appear as if things are not changing – amidst massive change! The mere fact that there is uncertainty seems to be the most troubling issue, as leaders don’t want to deal with it, nor know how.

This fear of uncertainty manifest itself in decisions to buy back stock, rather than invest in new products, services and markets. 24/7 Wall Street reported $34B in announced share buybacks in early February (2011 Stock Buybacks on Fire), only to update that to $40B by end of the month. Literally dozens of companies choosing to spend money on buying their own shares, which creates no economic value at all, rather than invest in something that could create growth! And these aren’t just companies with limited prospects, but include what have been considered growth entities like Pfizer, Astra-Zeneca, Electronic Arts, MedcoHealth, Verizon, Semantec, Yum! Brands, Quest, Kohl’s, Varian and Gamestop to name just a few.

All of these companies have opportunities to grow – heck, all companies have the opportunity to grow. But there is inherent uncertainty in spending money on something that might not work out. So, instead, they are taking hard earned cash flow and spending it on buying back the company stock. The real certainty, from this investment, is that it limits growth — and eventually will lead to a smaller company that’s worth less. Don’t forget, the only investment Sara Lee made under Brenda Barnes the last 5 years was buying back stock – and now the company has shriveled up to less than half its former size while the equity value has disintegrated. Nobody wins from share buybacks – with the possible exception of senior executives who have compensation tied to stock price.

At the Harvard Business Review Umar Haque admonishes leaders today “Fail Bigger Cheaper: A Three Word Manifesto.” Silicon valley investors, deep into understanding our change to an information economy, are far less interested in “scale” and more interested in how leaders, and their companies, are learning faster – so they see where they might fail faster – and then being nimble enough to adjust based upon what they learned. And not just to do more of the same better, but in order to identify bigger targets – larger opportunities – than originally imagined. Often the “failure” can direct the business into grander opportunities which have even higher payoffs.

That’s why we don’t see companies like Google, Apple, Netflix, Virgin, or Cisco buying back their own stock. They see opportunities, and they invest. They don’t all work out. Remember Google Wave? Looked great – didn’t make it – but so what? Google learns from what works, and what doesn’t, and uses that information to help it develop newer, more powerful growth markets.

Long ago Apple let its lack of success with the Newton PDA cause it to retrench into strictly Mac development – which took the company to the brink of disaster by 2000. Since then, by investing in new markets and new products, Apple has grown revenues and profits like crazy, making it more valuable than arch-rival Microsoft and close to being the most valuable publicly traded company.

Source: Silicon Alley Insider of BusinessInsider.com

Virgin used its success in music retailing to enter the trans-atlantic airline business (Virgin Atlantic). Since then it has launched dozens of businesses. Some didn’t work out – like Virgin Bridal – but many more have, such as Virgin Money, Virgin Mobil, Virgin Connect – to name just a handful of the many Virgin businesses that contribute to company growth and value creation.

Nobody wants to screw up. But, unless you do nothing, it is inevitable. No leader, or company, can create high value if they don’t overcome their fear of uncertainty and invest in innovation. But, hand-in-glove with such investing is the requirement to learn fast whether an innovation is working, or not. And to adapt. Some things need time for the market to develop, others need technology advances, and others need a change in direction toward different customers. It’s the ability to invest in uncertain situations, then pay attention to market feedback in order to recognize how well the idea is working, and constantly adapt to market learning that sets apart those companies creating wealth today.

Update 4/1/2011 – AOLSmallBusiness.com reminds us of another great adaptation story, based upon entering an unknown market and learning, in “Yes, Even Apple Screws Up Sometimes.” When personal computers were all text-based machines Apple introduced the Lisa as the first commercial computer to utilize on-screen icons, and a mouse for navigation, as well as other key productivity enhancers like the trash can. But the Lisa failed. Apple studied the market, kept what was desirable and modified what wasn’t, re-introducing the product as the Macintosh in 1984. The Mac was a huge success, creating enormous value for Apple which was undeterred by both the uncertainty of the fledgling PC market and its initial failure at various changes in the user interface.