by Adam Hartung | Jul 15, 2016 | Defend & Extend, Entertainment, Games, Innovation, Lock-in, Mobile, Trends

Poke’Mon Go is a new sensation. Just launched on July 6, the app is already the #1 app in the world – and it isn’t even available in most countries. In less than 2 weeks, from a standing start, Nintendo’s new app is more popular than both Facebook and Snapchat. Based on this success, Nintendo’s equity valuation has jumped 90% in this same short time period.

Some think this is just a fad, after all it is just 2 weeks old. Candy Crush came along and it seemed really popular. But after initial growth its user base stalled and the valuation fell by about 50% as growth in users, time on app and income all fell short of expectations. And, isn’t the world of gaming dominated by the likes of Sony and Microsoft?

Some think this is just a fad, after all it is just 2 weeks old. Candy Crush came along and it seemed really popular. But after initial growth its user base stalled and the valuation fell by about 50% as growth in users, time on app and income all fell short of expectations. And, isn’t the world of gaming dominated by the likes of Sony and Microsoft?

A bit of history

Nintendo launched the Wii in 2006 and it was a sensation. Gamers could do things not previously possible. Unit sales exceeded 20m units/year for 2006 through 2009. But Sony (PS4) and Microsoft (Xbox) both powered up their game consoles and started taking share from Nintendo. By 2011 Nintendo sale were down to 11.6m units, and in 2012 sales were off another 50%. The Wii console was losing relevance as competitors thrived.

Sony and Microsoft both invested heavily in their competition. Even though both were unprofitable at the business, neither was ready to concede the market. In fall, 2014 Microsoft raised the competitive ante, spending $2.5B to buy the maker of popular game Minecraft. Nintendo was becoming a market afterthought.

Meanwhile, back in 2009 Nintendo had 70% of the handheld gaming market with its 3DS product. But people started carrying the more versatile smartphones that could talk, text, email, execute endless apps and even had a lot of games – like Tetrus. The market for handheld games pretty much disappeared, dealing Nintendo another blow.

Competitor strategic errors

Fortunately, the bitter “fight to the death” war between Sony and Microsoft kept both focused on their historical game console business. Both kept investing in making the consoles more powerful, with more features, supporting more intense, lifelike games. Microsoft went so far as to implement in Windows 10 the capability for games to be played on Xbox and PCs, even though the PC gaming market had not grown in years. These massive investments were intended to defend their installed base of users, and extend the platform to attract new growth to the traditional, nearly 4 decade old market of game consoles that extends all the way back to Atari.

Both companies did little to address the growing market for mobile gaming. The limited power of mobile devices, and the small screens and poor sound systems made mobile seem like a poor platform for “serious gaming.” While game apps did come out, these were seen as extremely limited and poor quality, not at all competitive to the Sony or Microsoft products. Yes, theoretically Windows 10 would make gaming possible on a Microsoft phone. But the company was not putting investment there. Mobile gaming was simply not serious, and not of interest to the two Goliaths slugging it out for market share.

Building on trends makes all the difference

Back in 2014 I recognized that the console gladiator war was not good for either big company, and recommended Microsoft exit the market. Possibly seeing if Nintendo would take the business in order to remove the cash drain and distraction from Microsoft. Fortunately for Nintendo, that did not happen.

Nintendo observed the ongoing growth in mobile gaming. While Candy Crush may have been a game ignored by serious gamers, it nonetheless developed a big market of users who loved the product. Clearly this demonstrated there was an under-served market for mobile gaming. The mobile trend was real, and it’s gaming needs were unmet.

Simultaneously Nintendo recognized the trend to social. People wanted to play games with other people. And, if possible, the game could bring people together. Even people who don’t know each other. Rather than playing with unseen people located anywhere on the globe, in a pre-organized competition, as console games provided, why not combine the social media elements of connecting with those around you to play a game? Make it both mobile, and social. And the basics of Poke’Mon Go were born.

Then, build out the financial model. Don’t charge to play the game. But once people are in the game charge for in-game elements to help them be more successful. Just as Facebook did in its wildly successful social media game Farmville. The more people enjoyed meeting other people through the game, and the more they played, the more they would buy in-app, or in-game, elements. The social media aspect would keep them wanting to stay connected, and the game is the tool for remaining connected. So you use mobile to connect with vastly more people and draw them together, then social to keep them playing – and spending money.

The underserved market is vastly larger than the over-served market

Nintendo recognized that the under-served mobile gaming market is vastly larger than the overserved console market. Those console gamers have ever more powerful machines, but they are in some ways over-served by all that power. Games do so much that many people simply don’t want to take the time to learn the games, or invest in playing them sitting in a home or office. For many people who never became serious gaming hobbyists, the learning and intensity of serious gaming simply left them with little interest.

But almost everyone has a mobile phone. And almost everyone does some form of social media. And almost everyone enjoys a good game. Give them the right game, built on trends, to catch their attention and the number of potential customers is – literally – in the billions. And all they have to do is download the app. No expensive up-front cost, not much learning, and lots of fun. And thus in two weeks you have millions of new users. Some are traditional gamers. But many are people who would never be a serious gamer – they don’t want a new console or new complicated game. People of all ages and backgrounds could become immediate customers.

David can beat Goliath if you use trends

In the Biblical story, smallish David beat the giant Goliath by using a sling. His new technology allowed him to compete from far enough away that Goliath couldn’t reach David. And David’s tool allowed for delivering a fatal blow without ever touching the giant. The trend toward using tools for hunting and fighting allowed the younger, smaller competitor to beat the incumbent giant.

In business trends are just as important. Any competitor can study trends, see what people want, and then expand their thinking to discover a new way to compete. Nintendo lost the console war, and there was little value in spending vast sums to compete with Sony and Microsoft toe-to-toe. Nintendo saw the mobile game market disintegrate as smartphones emerged. It could have become a footnote in history.

But, instead Nintendo’s leaders built on trends to deliver a product that filled an unmet need – a game that was mobile and social. By meeting that need Nintendo has avoided direct competition, and found a way to dramatically grow its revenues. This is a story about how any competitor can succeed, if they learn how to leverage trends to bring out new products for under-served customers, and avoid costly gladiator competition trying to defend and extend past products.

by Adam Hartung | Jun 14, 2016 | Defend & Extend, Investing, Leadership, Web/Tech

Microsoft is buying Linked-In, and we should expect this to be a disaster.

It is clear why Linked-in agreed to be purchased. As revenues have grown, gross margins have dropped precipitously, and the company is losing money. And LInked-in still receives 2/3 of its revenue from recruiting ads (the balance is almost wholly subscription fees,) unable to find a wider advertiser base to support growth. Although membership is rising, monthly active users (MAUs, the most important gauge of social media growth) is only 9% – like Twitter, far below the 40% plus rate of Facebook and upcoming networks. With only 106M MAUs, Linked in is 1/3 the size of Twitter, and 1/15th the size of Facebook. And its $1.5B Lynda acquisition is far, far, far from recovering its investment – or even demonstrating viability as a business.

Even though the price is below the all-time highs for LNKD investors, Microsoft’s offer is far above recent trading prices and a big windfall for them.

But for Microsoft investors, this is a repeat of the pattern that continues to whittle away at their equity value.

Once upon a time, in a land far away, and barely remembered by young people, Microsoft OWNED the tech marketplace. Individuals and companies purchased PCs preloaded with Microsoft Windows 95, Microsoft Office, Microsoft Internet Explorer and a handful of other tools and trinkets. And as companies built networks they used PC servers loaded with Microsoft products. Computing was a Microsoft solution, beginning to end, for the vast majority of users.

Once upon a time, in a land far away, and barely remembered by young people, Microsoft OWNED the tech marketplace. Individuals and companies purchased PCs preloaded with Microsoft Windows 95, Microsoft Office, Microsoft Internet Explorer and a handful of other tools and trinkets. And as companies built networks they used PC servers loaded with Microsoft products. Computing was a Microsoft solution, beginning to end, for the vast majority of users.

But the world changed. Today PC sales continue their multi-year, accelerating decline, while some markets (such as education) are shifting to Chromebooks for low cost desktop/laptop computing, growing their sales and share. Meanwhile, mobile devices have been the growth market for years. Networks are largely public (rather than private) and storage is primarily in the cloud – and supplied by Amazon. Solutions are spread all around, from Google Drive to apps of every flavor and variety. People spend less computing cycles creating documents, spreadsheets and presentations, and a lot more cycles either searching the web or on Facebook, Instagram, WhatsApp, YouTube and Snapchat.

But Microsoft’s leadership still would like to capture that old world. They still hope to put the genie back in the bottle, and have everyone live and work entirely on Microsoft. And somehow they have deluded themselves into thinking that buying Linked-in will allow them to return to the “good old days.”

Microsoft has not done a good job of integrating its own solutions like Office 365, Skype, Sharepoint and Dynamics into a coherent, easy to use, and to some extent mobile, solution. Yet, somehow, investors are expected to believe that after buying Linked-in the two companies will integrate these solutions into the LInked-in social platform, enabling vastly greater adoption/use of Office 365 and Dynamics as they are tied to Linked-in Sales Navigator. Users will be thrilled to have their personal information analyzed by Microsoft big data tools, then sold to advertisers and recruiters. Meanwhile, corporations will come back to Microsoft in droves as they convert Linked-in into a comprehensive project management tool that uses Lynda to educate employees, and 365 to push materials to employees – and allow document collaboration – all across their mobile devices.

Do you really believe this? It might run on the Powerpoint operating system, but this vision will take an enormous amount of code integration. And with Linked-in operated as separate company within Microsoft, who is going to do this integration? This will involve a lot of technical capability, and based on previous performance it appears both companies lack the skills necessary to pull it off. How this mysterious, magical integration will happen is far, far from obvious, or explained in the announcement documents. Sounds a lot more like vaporware than a straightforward software project.

And who thinks that today’s users, from individuals to corporations, have a need for this vision? While it may sound good to Microsoft, have you heard Linked-in users saying they want to use 365 on Linked in? Or that they’ll continue to use Linked-in if forced to buy 365? Or that they want their personal information data mined for advertisers? Or that they desire integration with Dynamics to perform Linked-in based CRM? Or that they see a need for a social-network based project management tool that feeds up training documents or collaborative documents? Are people asking for an integrated, holistic solution from one vendor to replace their current mobile devices and mobile solutions that are upgraded by multiple vendors almost weekly?

And, who really thinks Microsoft is good at acquisition integration? Remember aQuantive? In 2007 Microsoft spent $6B (an 85% premium to market price) to purchase this digital ad agency in order to build its business in the fast growing digital ad space. Don’t feel bad if you don’t remember, because in 2012 Microsoft wrote it off. Of course, there was the buy-it-and-write-it-off pattern repeated with Nokia. Microsoft’s success at taking “bold moves” to expand beyond its core business has been nothing less than horrible. Even the $1.2B acquisition of Yammer in 2012 to make Sharepoint more collaborative and usable has been unsuccessful, even though rolled out for free to 365 users. Yammer is adding nothing to Microsoft’s sales or value as competitor Slack has reaped the growth in corporate messaging.

The only good news story about Microsoft acquisitions is that they missed spending $44B to buy Yahoo – which is now on the market for $5B. Whew, thank goodness that one got away!

Microsoft’s leadership primed the pump for this week’s announcement by having the Chairman talk about investing outside of the company’s core a couple of weeks ago. But the vast majority of analysts are now questioning this giant bet, at a price so high it will lower Microsoft’s earnings for 2 years. Analysts are projecting about a $2B revenue drop for $90B Microsoft next year, and this $26B acquisition will deliver only a $3B bump. Very, very expensive revenue replacement.

Despite all the lingo, Microsoft simply cannot seem to escape its past. Its acquisitions have all been designed to defend and extend its once great history – but now outdated. Customers don’t want the past, they are looking to the future. And no matter how hard they try, Microsoft’s leaders simply appear unable to define a future that is not tightly linked to the company’s past. So investors should expect Linked-In’s future to look a lot like aQuantive. Only this one is going to be the most painful yet in the long list of value transfer from Microsoft investors to the investors of acquired companies.

by Adam Hartung | Jun 9, 2016 | Innovation, Investing, Software, Teamwork

Last week Bloomberg broke a story about how Microsoft’s Chairman, John Thompson, was pushing company management for a faster transition to cloud products and services. He even recommended changes in spending might be in order.

Really? This is news?

Let’s see, how long has the move to mobile been around? It’s over a decade since Blackberry’s started the conversion to mobile. It was 10 years ago Amazon launched AWS. Heck, end of this month it will be 9 years since the iPhone was released – and CEO Steve Ballmer infamously laughed it would be a failure (due to lacking a keyboard.) It’s now been 2 years since Microsoft closed the Nokia acquisition, and just about a year since admitting failure on that one and writing off $7.5B And having failed to achieve even 3% market share with Windows phones, not a single analyst expects Microsoft to be a market player going forward.

So just now, after all this time, the Board is waking up to the need to change the resource allocation? That does seem a bit like looking into barn lock acquisition long after the horses are gone, doesn’t it?

The problem is that historically Boards receive almost all their information from management. Meetings are tightly scheduled affairs, and there isn’t a lot of time set aside for brainstorming new ideas. Or even for arguing with management assumptions. The work of governance has a lot of procedures related to compliance reporting, compensation, financial filings, senior executive hiring and firing – there’s a lot of rote stuff. And in many cases, surprisingly to many non-Directors, the company’s strategy may only be a topic once a year. And that is usually the result of a year long management controlled planning process, where results are reviewed and few challenges are expected. Board reviews of resource allocation are at the very, very tail end of management’s process, and commitments have often already been made – making it very, very hard for the Board to change anything.

And these planning processes are backward-oriented tools, designed to defend and extend existing products and services, not predict changes in markets. These processes originated out of financial planning, which used almost exclusively historical accounting information. In later years these programs were expanded via ERP (Enterprise Resource Planning) systems (such as SAP and Oracle) to include other information from sales, logistics, manufacturing and procurement. But, again, these numbers are almost wholly historical data. Because all the data is historical, the process is fixated on projecting, and thus defending, the old core of historical products sold to historical customers.

Copyright Adam Hartung

Efforts to enhance the process by including extensions to new products or new customers are very, very difficult to implement. The “owners” of the planning processes are inherent skeptics, inclined to base all forecasts on past performance. They have little interest in unproven ideas. Trying to plan for products not yet sold, or for sales to customers not yet in the fold, is considered far dicier – and therefore not worthy of planning. Those extensions are considered speculation – unable to be forecasted with any precision – and therefore completely ignored or deeply discounted.

And the more they are discounted, the less likely they receive any resource funding. If you can’t plan on it, you can’t forecast it, and therefore, you can’t really fund it. And heaven help some employee has a really novel idea for a new product sold to entirely new customers. This is so “white space” oriented that it is completely outside the system, and impossible to build into any future model for revenue, cost or – therefore – investing.

Take for example Microsoft’s recent deal to sell a bunch of patent rights to Xiaomi in order to have Xiaomi load Office and Skype on all their phones. It is a classic example of taking known products, and extending them to very nearby customers. Basically, a deal to sell current software to customers in new markets via a 3rd party. Rather than develop these markets on their own, Microsoft is retrenching out of phones and limiting its investments in China in order to have Xiaomi build the markets – and keeping Microsoft in its safe zone of existing products to known customers.

The result is companies consistently over-investment in their “core” business of current products to current customers. There is a wealth of information on those two groups, and the historical info is unassailable. So it is considered good practice, and prudent business, to invest in defending that core. A few small bets on extensions might be OK – but not many. And as a result the company investment portfolio becomes entirely skewed toward defending the old business rather than reaching out for future growth opportunities.

This can be disastrous if the market shifts, collapsing the old core business as customers move to different solutions. Such as, say, customers buying fewer PCs as they shift to mobile devices, and fewer servers as they shift to cloud services. These planning systems have no way to integrate trend analysis, and therefore no way to forecast major market changes – especially negative ones. And they lack any mechanism for planning on big changes to the product or customer portfolio. All future scenarios are based on business as it has been – a continuation of the status quo primarily – rather than honest scenarios based on trends.

How can you avoid falling into this dilemma, and avoiding the Microsoft trap? To break this cycle, reverse the inputs. Rather than basing resource allocation on financial planning and historical performance, resource allocation should be based on trend analysis, scenario planning and forecasts built from the future backward. If more time were spent on these plans, and engaging external experts like Board Directors in discussions about the future, then companies would be less likely to become so overly-invested in outdated products and tired customers. Less likely to “stay at the party too long” before finding another market to develop.

If your planning is future-oriented, rather than historically driven, you are far more likely to identify risks to your base business, and reduce investments earlier. Simultaneously you will identify new opportunities worthy of more resources, thus dramatically improving the balance in your investment portfolio. And you will be far less likely to end up like the Chairman of a huge, formerly market leading company who sounds like he slept through the last decade before recognizing that his company’s resource allocation just might need some change.

by Adam Hartung | May 10, 2016 | Defend & Extend, In the Swamp, Leadership, Lifecycle, Web/Tech

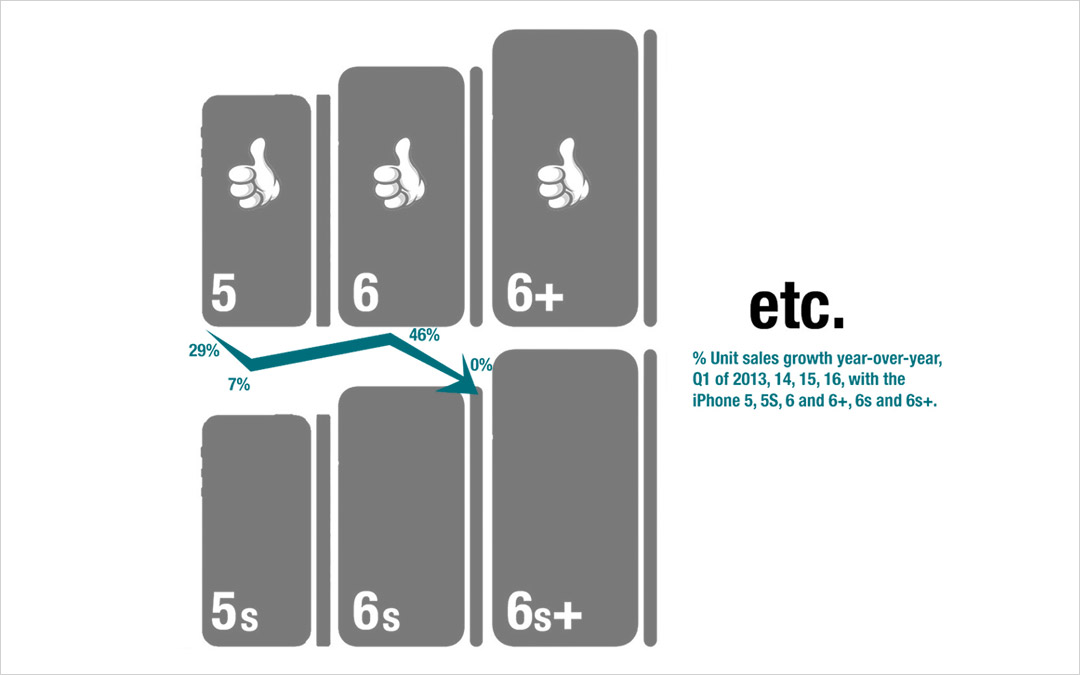

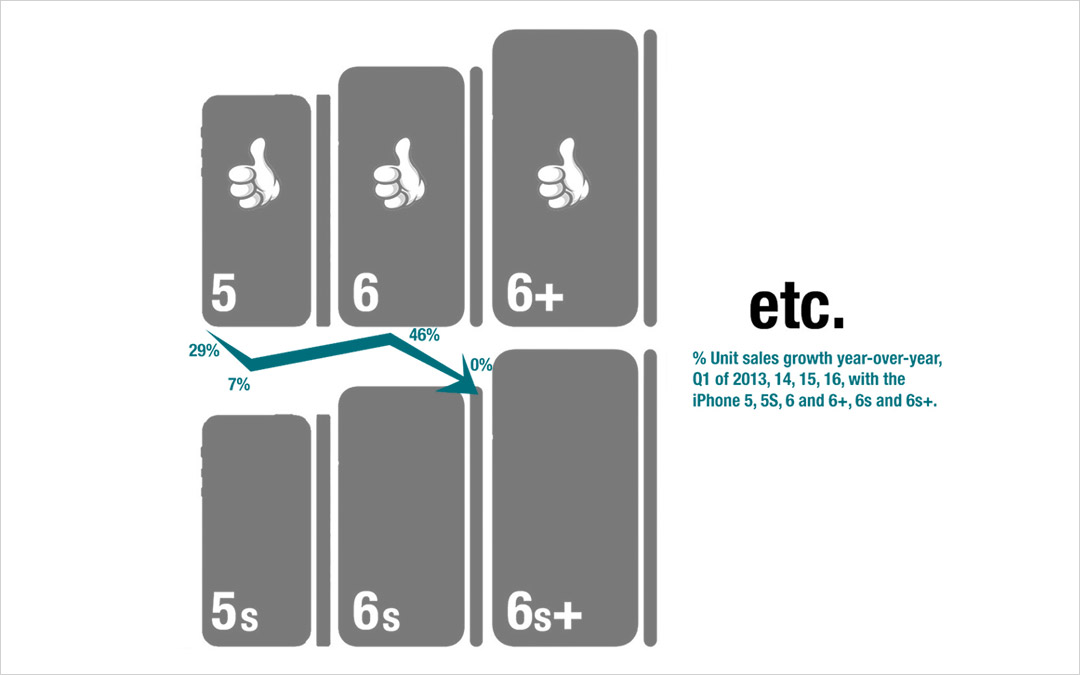

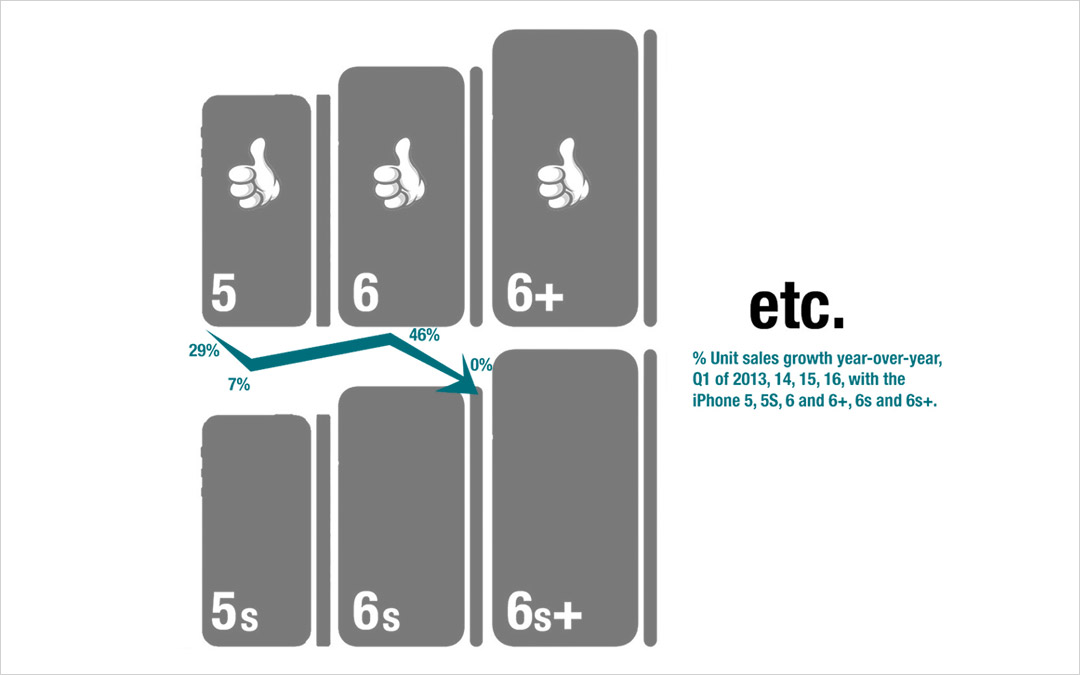

My last column focused on growth, and the risks inherent in a Growth stall. As I mentioned then, Apple will enter a Growth Stall if its revenue declines year-over-year in the current quarter. This forecasts Apple has only a 7% probability of consistently growing just 2%/year in the future.

This usually happens when a company falls into Defend & Extend (D&E) management. D&E management is when the bulk of management attention, and resources, flow into protecting the “core” business by seeking ways to use sustaining innovations (rather than disruptive innovations) to defend current customers and extend into new markets. Unfortunately, this rarely leads to high growth rates, and more often leads to compressed margins as growth stalls. Instead of working on breakout performance products, efforts are focused on ways to make new versions of old products that are marginally better, faster or cheaper.

Using the D&E lens, we can identify what looks like a sea change in Apple’s strategy.

Using the D&E lens, we can identify what looks like a sea change in Apple’s strategy.

For example, Apple’s CEO has trumpeted the company’s installed base of 1B iPhones, and stated they will be a future money maker. He bragged about the 20% growth in “services,” which are iPhone users taking advantage of Apple Music, iCloud storage, Apps and iTunes. This shows management’s desire to extend sales to its “installed base” with sustaining software innovations. Unfortunately, this 20% growth was a whopping $1.2B last quarter, which was 2.4% of revenues. Not nearly enough to make up for the decline in “core” iPhone, iPad or Mac sales of approximately $9.5B.

Apple has also been talking a lot about selling in China and India. Unfortunately, plans for selling in India were at least delayed, if not thwarted, by a decision on the part of India’s regulators to not allow Apple to sell low cost refurbished iPhones in the country. Fearing this was a cheap way to dispose of e-waste they are pushing Apple to develop a low-cost new iPhone for their market. Either tactic, selling the refurbished products or creating a cheaper version, are efforts at extending the “core” product sales at lower margins, in an effort to defend the historical iPhone business. Neither creates a superior product with new features, functions or benefits – but rather sustains traditional product sales.

Of even greater note was last week’s announcement that Apple inked a partnership with SAP to develop uses for iPhones and iPads built on the SAP ERP (Enterprise Resource Planning) platform. This announcement revealed that SAP would ask developers on its platform to program in Swift in order to support iOS devices, rather than having a PC-first mentality.

This announcement builds on last year’s similar announcement with IBM. Now 2 very large enterprise players are building applications on iOS devices. This extends the iPhone, a product long thought of as great for consumers, deeply into enterprise sales. A market long dominated by Microsoft. With these partnerships Apple is growing its developer community, while circumventing Microsoft’s long-held domain, promoting sales to companies as well as individuals.

And Apple has shown a willingness to help grow this market by introducing the iPhone 6se which is smaller and cheaper in order to obtain more traction with corporate buyers and corporate employees who have been iPhone resistant. This is a classic market extension intended to sustain sales with more applications while making no significant improvements in the “core” product itself.

And Apple’s CEO has said he intends to make more acquisitions – which will surely be done to shore up weaknesses in existing products and extend into new markets. Although Apple has over $200M of cash it can use for acquisitions, unfortunately this tactic can be a very difficult way to actually find new growth. Each would be targeted at some sort of market extension, but like Beats the impact can be hard to find.

Remember, after all revenue gains and losses were summed, Apple’s revenue fell $7.6B last quarter. Let’s look at some favorite analyst acquisition targets to explain:

- Box could be a great acquisition to help bring more enterprise developers to Apple. Box is widely used by enterprises today, and would help grow where iCloud is weak. IBM has already partnered with Box, and is working on applications in areas like financial services. Box is valued at $1.45B, so easily affordable. But it also has only $300M of annual revenue. Clearly Apple would have to unleash an enormous development program to have Box make any meaningful impact in a company with over $500B of revenue. Something akin of Instagram’s growth for Facebook would be required. But where Instagram made Facebook a pic (versus words) site, it is unclear what major change Box would bring to Apple’s product lines.

- Fitbit is considered a good buy in order to put some glamour and growth onto iWatch. Of course, iWatch already had first year sales that exceeded iPhone sales in its first year. But Apple is now so big that all numbers have to be much bigger in order to make any difference. With a valuation of $3.7B Apple could easily afford FitBit. But FitBit has only $1.9B revenue. Given that they are different technologies, it is unclear how FitBit drives iWatch growth in any meaningful way – even if Apple converted 100% of Fitbit users to the iWatch. There would need to be a “killer app” in development at FitBit that would drive $10B-$20B additional annual revenue very quickly for it to have any meaningful impact on Apple.

- GoPro is seen as a way to kick up Apple’s photography capabilities in order to make the iPhone more valuable – or perhaps developing product extensions to drive greater revenue. At a $1.45B valuation, again easily affordable. But with only $1.6B revenue there’s just not much oomph to the Apple top line. Even maximum Apple Store distribution would probably not make an enormous impact. It would take finding some new markets in industry (enterprise) to build on things like IoT to make this a growth engine – but nobody has said GoPro or Apple have any innovations in that direction. And when Amazon tried to build on fancy photography capability with its FirePhone the product was a flop.

- Tesla is seen as the savior for the Apple Car – even though nobody really knows what the latter is supposed to be. Never mind the actual business proposition, some just think Elon Musk is the perfect replacement for the late Steve Jobs. After all the excitement for its products, Tesla is valued at only $28.4B, so again easily affordable by Apple. And the thinking is that Apple would have plenty of cash to invest in much faster growth — although Apple doesn’t invest in manufacturing and has been the king of outsourcing when it comes to actually making its products. But unfortunately, Tesla has only $4B revenue – so even a rapid doubling of Tesla shipments would yield a mere 1.6% increase in Apple’s revenues.

- In a spree, Apple could buy all 4 companies! Current market value is $35B, so even including a market premium $55B-$60B should bring in the lot. There would still be plenty of cash in the bank for growth. But, realize this would add only $8B of annual revenue to the current run rate – barely 25% of what was needed to cover the gap last quarter – and less than 2% incremental growth to the new lower run rate (that magic growth percentage to pull out of a Growth Stall mentioned earlier in this column.)

Such acquisitions would also be problematic because all have P/E (price/earnings) ratios far higher than Apple’s 10.4. FitBit is 24, GoPro is 43, and both Box and Tesla are infinite because they lose money. So all would have a negative impact on earnings per share, which theoretically should lower Apple’s P/E even more.

Acquisitions get the blood pumping for investment bankers and media folks alike – but, truthfully, it is very hard to see an acquisition path that solves Apple’s revenue problem.

All of Apple’s efforts big efforts today are around sustaining innovations to defend & extend current products. No longer do we hear about gee whiz innovations, nor do we hear about growth in market changing products like iBeacons or ApplePay. Today’s discussions are how to rejuvenate sales of products that are several versions old. This may work. Sales may recover via growth in India, or a big pick-up in enterprise as people leave their PCs behind. It could happen, and Apple could avoid its Growth Stall.

But investors have the right to be concerned. Apple can grow by defending and extending the iPhone market only so long. This strategy will certainly affect future margins as prices, on average, decline. In short, investors need to know what will be Apple’s next “big thing,” and when it is likely to emerge. It will take something quite significant for Apple to maintain it’s revenue, and profit, growth.

The good news is that Apple does sell for a lowly P/E of 10 today. That is incredibly low for a company as profitable as Apple, with such a large installed base and so many market extensions – even if its growth has stalled. Even if Apple is caught in the Innovator’s Dilemma (i.e. Clayton Christensen) and shifting its strategy to defending and extending, it is very lowly valued. So the stock could continue to perform well. It just may never reach the P/E of 15 or 20 that is common for its industry peers, and investors envisioned 2 or 3 years ago. Unless there is some new, disruptive innovation in the pipeline not yet revealed to investors.

by Adam Hartung | May 8, 2015 | Current Affairs, Defend & Extend, Food and Drink, In the Swamp, In the Whirlpool, Leadership

McDonald’s just had another lousy quarter. All segments saw declining traffic, revenues fell 11%. Profits were off 33%. Pretty well expected, given its established growth stall.

A new CEO is in place, and he announced is turnaround plan to fix what ails the burger giant. Unfortunately, his plan has been panned by just about everyone. Unfortunately, its a “me too” plan that we’ve seen far too often – and know doesn’t work:

- Reorganize to cut costs. By reshuffling the line-up, and throwing out a bunch of bodies management formerly said were essential, but now don’t care about, they hope to save $300M/year (out of a $4.5B annual budget.)

- Sell off 3,500 stores McDonald’s owns and operate (about 10% of the total.) This will further help cut costs as the operating budgets shift to franchisees, and McDonald’s book unit sales creating short-term, one-time revenues into 2018.

- Keep mucking around with the menu. Cut some items, add some items, try a bunch of different stuff. Hope they find something that sells better.

- Try some service ideas in which nobody really shows any faith, like adding delivery and/or 24 hour breakfast in some markets and some stores.

Needless to say, none of this sounds like it will do much to address quarter after quarter of sales (and profit) declines in an enormously large company. We know people are still eating in restaurants, because competitors like 5 Guys, Meatheads, Burger King and Shake Shack are doing really, really well. But they are winning primarily because McDonald’s is losing. Even though CEO Easterbrook said “our business model is enduring,” there is ample reason to think McDonald’s slide will continue.

Needless to say, none of this sounds like it will do much to address quarter after quarter of sales (and profit) declines in an enormously large company. We know people are still eating in restaurants, because competitors like 5 Guys, Meatheads, Burger King and Shake Shack are doing really, really well. But they are winning primarily because McDonald’s is losing. Even though CEO Easterbrook said “our business model is enduring,” there is ample reason to think McDonald’s slide will continue.

Possibly a slide into oblivion. Think it can’t happen? Then what happened to Howard Johnson’s? Bob’s Big Boy? Woolworth’s? Montgomery Wards? Size, and history, are absolutely no guarantee of a company remaining viable.

In fact, the odds are wildly against McDonald’s this time. Because this isn’t their first growth stall. And the way they saved the company last time was a “fire sale” of very valuable growth assets to raise cash that was all spent to spiffy up the company for one last hurrah – which is now over. And there isn’t really anything left for McDonald’s to build upon.

Go back to 2000 and McDonald’s had a lot of options. They bought Chipotle’s Mexican Grill in 1998, Donato’s Pizza in 1999 and Boston Market in 2000. These were all growing franchises. Growing a LOT faster, and more profitably, than McDonald’s stores. They were on modern trends for what people wanted to eat, and how they wanted to be served. These new concepts offered McDonald’s fantastic growth vehicles for all that cash the burger chain was throwing off, even as its outdated yellow stores full of playgrounds with seats bolted to the floors and products for 99cents were becoming increasingly not only outdated but irrelevant.

But in a change of leadership McDonald’s decided to sell off all these concepts. Donato’s in 2003, Chipotle went public in 2006 and Boston Market was sold to a private equity firm in 2007. All of that money was used to fund investments in McDonald’s store upgrades, additional supply chain restructuring and advertising. The “strategy” at that time was to return to “strategic focus.” Something that lots of analysts, investors and old-line franchisees love.

But look what McDonald’s leaders gave up via this decision to re-focus. McDonald’s received $1.5B for Chipotle. Today Chipotle is worth $20B and is one of the most exciting fast food chains in the marketplace (based on store growth, revenue growth and profitability – as well as customer satisfaction scores.) The value of all of the growth gains that occurred in these 3 chains has gone to other people. Not the investors, employees, suppliers or franchisees of McDonald’s.

We have to recognize that in the mid-2000s McDonald’s had the option of doing 180degrees opposite what it did. It could have put its resources into the newer, more exciting concepts and continued to fidget with McDonald’s to defend and extend its life even as trends went the other direction. This would have allowed investors to reap the gains of new store growth, and McDonald’s franchisees would have had the option to slowly convert McDonald’s stores into Donato’s, Chipotle’s or Boston Market. Employees would have been able to work on growing the new brands, creating more revenue, more jobs, more promotions and higher pay. And suppliers would have been able to continue growing their McDonald’s corporate business via new chains. Customers would have the benefit of both McDonald’s and a well run transition to new concepts in their markets. This would have been a win/win/win/win/win solution for everyone.

But it was the lure of “focus” and “core” markets that led McDonald’s leadership to make what will likely be seen historically as the decision which sent it on the track of self-destruction. When leaders focus on their core markets, and pull out all the stops to try defending and extending a business in a growth stall, they take their eyes off market trends. Rather than accepting what people want, and changing in all ways to meet customer needs, leaders keep fiddling with this and that, and hoping that cost cutting and a raft of operational activities will save the business as they keep focusing ever more intently on that old core business. But, problems keep mounting because customers, quite simply, are going elsewhere. To competitors who are implementing on trends.

The current CEO likes to describe himself as an “internal activist” who will challenge the status quo. But he then proves this is untrue when he describes the future of McDonald’s as a “modern, progressive burger company.” Sorry dude, that ship sailed years ago when competitors built the market for higher-end burgers, served fast in trendier locations. Just like McDonald’s 5-years too late effort to catch Starbucks with McCafe which was too little and poorly done – you can’t catch those better quality burger guys now. They are well on their way, and you’re still in port asking for directions.

McDonald’s is big, but when a big ship starts taking on water it’s no less likely to sink than a small ship (i.e. Titanic.) And when a big ship is badly steered by its captain it flounders, and sinks (i.e. Costa Concordia.) Those who would like to think that McDonald’s size is a benefit should recognize that it is this very size which now keeps McDonald’s from doing anything effective to really change the company. Its efforts (detailed above) are hemmed in by all those stores, franchisees, commitment to old processes, ingrained products hard to change due to installed equipment base, and billions spent on brand advertising that has remained a constant even as McDonald’s lost relevancy. It is now sooooooooo hard to make even small changes that the idea of doing more radical things that analysts are requesting simply becomes impossible for existing management.

And these leaders, frankly, aren’t even going to try. They are deeply wedded, committed, to trying to succeed by making McDonald’s more McDonald’s. They are of the company and its history. Not the CEO, or anyone on his team, reached their position by introducing a revolutionary new product, much less a new concept – or for that matter anything new. They are people who “execute” and work to slowly improve what already exists. That’s why they are giving even more decision-making control to franchisees via selling company stores in order to raise cash and cut costs – rather than using those stores to introduce radical change.

These are not “outside thinkers” that will consider the kinds of radical changes Louis V. Gerstner, a total outsider, implemented at IBM – changing the company from a failing mainframe supplier into an IT services and software company. Yet that is the only thing that will turn around McDonald’s. The Board blew it once before when it sold Chipotle, et.al. and put in place a core-focused CEO. Now McDonald’s has fewer resources, a lot fewer options, and the gap between what it offers and what the marketplace wants is a lot larger.

Some think this is just a fad, after all it is just 2 weeks old. Candy Crush came along and it seemed really popular. But after initial growth its user base stalled and the valuation fell by about 50% as growth in users, time on app and income all fell short of expectations. And, isn’t the world of gaming dominated by the likes of Sony and Microsoft?

Some think this is just a fad, after all it is just 2 weeks old. Candy Crush came along and it seemed really popular. But after initial growth its user base stalled and the valuation fell by about 50% as growth in users, time on app and income all fell short of expectations. And, isn’t the world of gaming dominated by the likes of Sony and Microsoft?

Once upon a time, in a land far away, and barely remembered by young people, Microsoft OWNED the tech marketplace. Individuals and companies purchased PCs preloaded with Microsoft Windows 95, Microsoft Office, Microsoft Internet Explorer and a handful of other tools and trinkets. And as companies built networks they used PC servers loaded with Microsoft products. Computing was a Microsoft solution, beginning to end, for the vast majority of users.

Once upon a time, in a land far away, and barely remembered by young people, Microsoft OWNED the tech marketplace. Individuals and companies purchased PCs preloaded with Microsoft Windows 95, Microsoft Office, Microsoft Internet Explorer and a handful of other tools and trinkets. And as companies built networks they used PC servers loaded with Microsoft products. Computing was a Microsoft solution, beginning to end, for the vast majority of users.