by Adam Hartung | May 15, 2016 | In the Swamp, Investing, real estate, Retail

Last week Sears announced sales and earnings. And once again, the news was all bad. The stock closed at a record, all time low. One chart pretty much sums up the story, as investors are now realizing bankruptcy is the most likely outcome.

Chart Source: Yahoo Finance 5/13/16

Quick Rundown: In January, 2002 Kmart is headed for bankruptcy. Ed Lampert, CEO of hedge fund ESL, starts buying the bonds. He takes control of the company, makes himself Chairman, and rapidly moves through proceedings. On May 1, 2003, KMart begins trading again. The shares trade for just under $15 (for this column all prices are adjusted for any equity transactions, as reflected in the chart.)

Lampert quickly starts hacking away costs and closing stores. Revenues tumble, but so do costs, and earnings rise. By November, 2004 the stock has risen to $90. Lampert owns 53% of Kmart, and 15% of Sears. Lampert hires a new CEO for Kmart, and quickly announces his intention to buy all of slow growing, financially troubled Sears.

In March, 2005 Sears shareholders approve the deal. The stock trades for $126. Analysts praise the deal, saying Lampert has “the Midas touch” for cutting costs. Pumped by most analysts, and none moreso than Jim Cramer of “Mad Money” fame (Lampert’s former roommate,) in 2 years the stock soars to $178 by April, 2007. So far Lampert has done nothing to create value but relentlessly cut costs via massive layoffs, big inventory reductions, delayed payments to suppliers and store closures.

Homebuilding falls off a cliff as real estate values tumble, and the Great Recession begins. Retailers are creamed by investors, and appliance sales dependent Sears crashes to $33.76 in 18 months. On hopes that a recovering economy will raise all boats, the stock recovers over the next 18 months to $113 by April, 2010. But sales per store keep declining, even as the number of stores shrinks. Revenues fall faster than costs, and the stock falls to $43.73 by January, 2013 when Lampert appoints himself CEO. In just under 2.5 years with Lampert as CEO and Chairman the company’s sales keep falling, more stores are closed or sold, and the stock finds an all-time low of $11.13 – 25% lower than when Lampert took KMart public almost exactly 13 years ago – and 94% off its highs.

What happened?

Sears became a retailing juggernaut via innovation. When general stores were small and often far between, and stocking inventory was precious, Sears invented mail order catalogues. Over time almost every home in America was receiving 1, or several, catalogues every year. They were a major source of purchases, especially by people living in non-urban communities. Then Sears realized it could open massive stores to sell all those things in its catalogue, and the company pioneered very large, well stocked stores where customers could buy everything from clothes to tools to appliances to guns. As malls came along, Sears was again a pioneer “anchoring” many malls and obtaining lower cost space due to the company’s ability to draw in customers for other retailers.

To help customers buy more Sears created customer installment loans. If a young couple couldn’t afford a stove for their new home they could buy it on terms, paying $10 or $15 a month, long before credit cards existed. The more people bought on their revolving credit line, and the more they paid Sears, the more Sears increased their credit limit. Sears was the “go to” place for cash strapped consumers. (Eventually, this became what we now call the Discover card.)

In 1930 Sears expanded the Allstate tire line to include selling auto insurance – and consumers could not only maintain their car at Sears they could insure it as well. As its customers grew older and more wealthy, many needed help with financia advice so in 1981 Sears bought Dean Witter and made it possible for customers to figure out a retirement plan while waiting for their tires to be replaced and their car insurance to update.

To put it mildly, Sears was the most innovative retailer of all time. Until the internet came along. Focused on its big stores, and its breadth of products and services, Sears kept trying to sell more stuff through those stores, and to those same customers. Internet retailing seemed insignificantly small, and unappealing. Heck, leadership had discontinued the famous catalogues in 1993 to stop store cannibalization and push people into locations where the company could promote more products and services. Focusing on its core customers shopping in its core retail locations, Sears leadership simply ignored upstarts like Amazon.com and figured its old success formula would last forever.

But they were wrong. The traditional Sears market was niched up across big box retailers like Best Buy, clothiers like Kohls, tool stores like Home Depot, parts retailers like AutoZone, and soft goods stores like Bed, Bath & Beyond. The original need for “one stop shopping” had been overtaken by specialty retailers with wider selection, and often better pricing. And customers now had credit cards that worked in all stores. Meanwhile, for those who wanted to shop for many things from home the internet had taken over where the catalogue once began. Leaving Sears’ market “hollowed out.” While KMart was simply overwhelmed by the vast expansion of WalMart.

What should Lampert have done?

There was no way a cost cutting strategy would save KMart or Sears. All the trends were going against the company. Sears was destined to keep losing customers, and sales, unless it moved onto trends. Lampert needed to innovate. He needed to rapidly adopt the trends. Instead, he kept cutting costs. But revenues fell even faster, and the result was huge paper losses and an outpouring of cash.

To gain more insight, take a look at Jeff Bezos. But rather than harp on Amazon.com’s growth, look instead at the leadership he has provided to The Washington Post since acquiring it just over 2 years ago. Mr. Bezos did not try to be a better newspaper operator. He didn’t involve himself in editorial decisions. Nor did he focus on how to drive more subscriptions, or sell more advertising to traditional customers. None of those initiatives had helped any newspaper the last decade, and they wouldn’t help The Washington Post to become a more relevant, viable and profitable company. Newspapers are a dying business, and Bezos could not change that fact.

Mr. Bezos focused on trends, and what was needed to make The Washington Post grow. Media is under change, and that change is being created by technology. Streaming content, live content, user generated content, 24×7 content posting (vs. deadlines,) user response tracking, readers interactivity, social media connectivity, mobile access and mobile content — these are the trends impacting media today. So that was where he had leadership focus. The Washington Post had to transition from a “newspaper” company to a “media and technology company.”

So Mr. Bezos pushed for hiring more engineers – a lot more engineers – to build apps and tools for readers to interact with the company. And the use of modern media tools like headline testing. As a result, in October, 2015 The Washington Post had more unique web visitors than the vaunted New York Times. And its lead is growing. And while other newspapers are cutting staff, or going out of business, the Post is adding writers, editors and engineers. In a declining newspaper market The Washington Post is growing because it is using trends to transform itself into a company readers (and advertisers) value.

CEO Lampert could have chosen to transform Sears Holdings. But he did not. He became a very, very active “hands on” manager. He micro-managed costs, with no sense of important trends in retail. He kept trying to take cash out, when he needed to invest in transformation. He should have sold the real estate very early, sensing that retail was moving on-line. He should have sold outdated brands under intense competitive pressure, such as Kenmore, to a segment supplier like Best Buy. He then should have invested that money in technology. Sears should have been a leader in shopping apps, supplier storefronts, and direct-to-customer distribution. Focused entirely on defending Sears’ core, Lampert missed the market shift and destroyed all the value which initially existed in the great retail merger he created.

Impact?

Every company must understand critical trends, and how they will apply to their business. Nobody can hope to succeed by just protecting the core business, as it can be made obsolete very, very quickly. And nobody can hope to change a trend. It is more important than ever that organizations spend far less time focused on what they did, and spend a lot more time thinking about what they need to do next. Planning needs to shift from deep numerical analysis of the past, and a lot more in-depth discussion about technology trends and how they will impact their business in the next 1, 3 and 5 years.

Sears Holdings was a 13 year ride. Investor hope that Lampert could cut costs enough to make Sears and KMart profitable again drove the stock very high. But the reality that this strategy was impossible finally drove the value lower than when the journey started. The debacle has ruined 2 companies, thousands of employees’ careers, many shopping mall operators, many suppliers, many communities, and since 2007 thousands of investor’s gains. Four years up, then 9 years down. It happened a lot faster than anyone would have imagined in 2003 or 2004. But it did.

And it could happen to you. Invert your strategic planning time. Spend 80% on trends and scenario planning, and 20% on historical analysis. It might save your business.

by Adam Hartung | Mar 13, 2016 | In the Swamp, Leadership, Travel

United Continental Holdings is the most recent public company to come under attack by hedge funds. Last week Altimeter Capital and PAR Capital announced they were using their combined 7.1% ownership of United to propose a slate of 6 new directors to the company’s board. As is common in such hedge fund moves, they expressed strongly their lack of confidence in United’s board, and pointed out multiple years of underperformance.

United’s leadership is certainly in a tough place. The airline consistently ranks near the bottom in customer satisfaction, and on-time performance. It has struggled for years with labor strife, and the mechanics union just rejected their proposed contract – again. The flight attendant’s union has been in mediation for months. And few companies have had more consistently bad public relations, as customers have loudly complained about how they are treated – including one fellow making a music and speaking career out of how he was abused by United personnel for months after they destroyed his guitar.

United’s leadership is certainly in a tough place. The airline consistently ranks near the bottom in customer satisfaction, and on-time performance. It has struggled for years with labor strife, and the mechanics union just rejected their proposed contract – again. The flight attendant’s union has been in mediation for months. And few companies have had more consistently bad public relations, as customers have loudly complained about how they are treated – including one fellow making a music and speaking career out of how he was abused by United personnel for months after they destroyed his guitar.

But is changing the directors going to change the company? Or is it just changing the guest list for an haute couture affair? Should customers, employees, suppliers and investors expect things to really improve, or is this a selection between the devil and the deep blue sea?

Much was made of the fact that one of the proposed new directors is the former CEO of Continental, Gordon Bethune, who was very willing to speak out loudly and negatively regarding United’s current board. But Mr. Bethune is 74 years old. Today most companies have mandatory director retirement somewhere between age 68 and 72. Retired since 2004, is Mr. Bethune really in step with the needs of airline customers today? Does he really have a current understanding of how the best performing airlines keep customers happy while making money?

And, don’t forget, Mr. Bethune hand picked Mr. Jeff Smisek to replace him at Continental. Mr. Smisek was the fellow who took over Mr. Bethune’s board seat in 2004 after being appointed President and COO when Mr. Bethune retired. Smisek became CEO in 2010, and CEO of United Continental after the merger, and led the ongoing deterioration in United’s performance as well as declining employee moral. And then there’s that pesky problem of Mr. Smisek bribing government officials to improve United’s gate situation in Newark, NJ which caused him to be fired by the current board. Is it coincidental that this attack on the Board did not happen for years, but happens now that there is a new CEO – who happens to be recently recovering from a heart replacement?

Although Mr. Bethune has commented that the new board would be one that understands the airline industry, the slate does not reflect this. Mr. Gerstner is head of Altimiter and by all accounts appears to be a finance expert. That was the background Ed Lampert brought to Sears, another big Chicago company, when he took over that board. And that has not worked out too well at all for any constituents – including investors.

One can give great kudos to the hedge funds for proposing a very diverse slate. Half the proposed directors are either female or of color. And, other than Mr. Bethune, the slate is pretty young – with 2 proposed directors under age 50. Congratulations on achieving diversification! But a deeper look can cause us to wonder exactly what these directors bring to the challenges, and what they are likely to want to change at United.

Rodney O’Neal was the former CEO of Delphi Automotive. A lifelong automotive manager and executive, he graduated from the General Motors Institute and spent his career at GM before going to the parts unit GM had created in 1997 as a Vice President. Many may have forgotten that Delphi famously filed for bankruptcy in 2005, and proceeded to close over half its U.S. plants, then close or sell almost all of the other half in 2006. Mr. O’Neal became CEO in 2007, after which the company closed its plants in Spain despite having signed a commitment letter not to do so. He was CEO in 2008 when the company sued its shareholders. And in 2009 when the company sold its core assets to private investors, then dumped assets into the bankrupt GM, cancelled the stock and renamed the old Delphi DPH Holdings. Cutting, selling and reorganizing seem to be his dominant executive experience.

Barney Harford is a young, talented tech executive. He headed Orbitz, where Mr. Gerstner was on the board. Orbitz was originally created as the Travelocity and Expedia killer by the major airlines. Unfortunately, it never did too well and Mr. Harford actually changed the company direction from primarily selling airline tickets to selling hotel rooms.

It is always good to see more women proposed for board positions. However, Ms. Brenda Yester Baty is an executive with Lennar, a very large Florida-based home builder. And Ms. Tina Stark leads Sherpa Foundry which has a 1 page web site saying “Sherpa Foundry builds

bridges between the world’s leading Corporations and the Innovation Economy.” What that means leaves a lot of room for one’s imagination, and precious little specifics. What either of these people have to do with creating a major turnaround in the operations of United is unclear.

There is no doubt that United is ripe for change. Replacing the CEO was clearly a step in the right direction – if a bit late. But one has to wonder if the new directors are there to make some specific change? If so, what kind of change? Despite the rough rhetoric, there has been no proclamation of what the new director slate would actually do differently. No discussion of a change in strategy – or any changes in any operating characteristics. Just vague statements about better governance.

Historically most activists take firm aim at cutting costs. And this is probably why the 2 largest unions have already denounced the new slate, and put their full support behind the existing board of directors. After so many years of ill-will between management and labor at United, one would wonder why these unions would not welcome change. Unless they fear the new board will be mostly focused on cost-cutting, and further attempts at downsizing and pay/benefits reductions.

Investors will most likely get to vote on this decision. Keep existing board members, or throw them out in favor of a new slate? One would like to see United’s reputation, and operations, improve dramatically. But is changing out 6 directors the answer? Or are investors facing a vote that has them selecting between 2 less than optimal options? It would be good if there was less rhetoric, and more focus on actual proposals for change.

by Adam Hartung | Feb 11, 2016 | Current Affairs, In the Whirlpool, Leadership, Lock-in

USAToday alerted investors that when Sears Holdings reports results 2/25/16 they will be horrible. Revenues down another 8.7% vs. last year. Same store sales down 7.1%. To deal with ongoing losses the company plans to close another 50 stores, and sell another $300million of assets. For most investors, employees and suppliers this report could easily be confused with many others the last few years, as the story is always the same. Back in January, 2014 CNBC headlined “Tracking the Slow Death of an Icon” as it listed all the things that went wrong for Sears in 2013 – and they have not changed two years later. The brand is now so tarnished that Sears Holdings is writing down the value of the Sears name by another $200million – reducing intangible value from the $4B at origination in 2004 to under $2B.

This has been quite the fall for Sears. When Chairman Ed Lampert fashioned the deal that had formerly bankrupt Kmart buying Sears in November, 2004 the company was valued at $11billion and 3,500 stores. Today the company is valued at $1.6billion (a decline of over 85%) and according to Reuters has just under 1,700 stores (a decline of 51%.) According to Bloomberg almost no analysts cover SHLD these days, but one who does (Greg Melich at Evercore ISI) says the company is no longer a viable business, and expects bankruptcy. Long-term Sears investors have suffered a horrible loss.

When I started business school in 1980 finance Professor Bill Fruhan introduced me to a concept that had never before occurred to me. Value Destruction. Through case analysis the good professor taught us that leadership could make decisions that increased company valuation. Or, they could make decisions that destroyed shareholder value. As obvious as this seems, at the time I could not imagine CEOs and their teams destroying shareholder value. It seemed anathema to the entire concept of business education. Yet, he quickly made it clear how easily misguided leaders could create really bad outcomes that seriously damaged investors.

As a case study in bad leadership, Sears under Chairman Lampert offers great lessons in Value Destruction that would serve Professor Fruhan’s teachings well:

As a case study in bad leadership, Sears under Chairman Lampert offers great lessons in Value Destruction that would serve Professor Fruhan’s teachings well:

1 – Micro-management in lieu of strategy. Mr. Lampert has been merciless in his tenacity to manage every detail at Sears. Daily morning phone calls with staff, and ridiculously tight controls that eliminate decision making by anyone other than the top officers. Additionally, every decision by the officers was questioned again and again. Explanations took precedent over action as micro-management ate up management’s time, rather than trying to run a successful company. While store employees and low- to mid-level managers could see competition – both traditional and on-line – eating away at Sears customers and core sales, they were helpless to do anything about it. Instead they were forced to follow orders given by people completely out of touch with retail trends and customer needs. Whatever chance Sears and Kmart had to grow the chain against intense competition it was lost by the Chairman’s need to micro-manage.

2 – Manage-by-the-numbers rather than trends. Mr. Lampert was a finance expert and former analyst turned hedge fund manager and investor. He truly believed that if he had enough numbers, and he studied them long enough, company success would ensue. Unfortunately, trends often are not reflected in “the numbers” until it is far, far too late to react. The trend to stores that were cleaner, and more hip with classier goods goes back before Lampert’s era, but he completely missed the trend that drove up sales at Target, H&M and even Kohl’s because he could not see that trend reflected in category sales or cost ratios. Merchandising – from buying to store layout and shelf positioning – are skills that go beyond numerical analysis but are critical to retail success. Additionally, the trend to on-line shopping goes back 20 years, but the direct impact on store sales was not obvious until customers had long ago converted. By focusing on numbers, rather than trends, Sears was constantly reacting rather than being proactive, and thus constantly retreating, cutting stores and cutting product lines.

3 – Seeking confirmation rather than disagreement. Mr. Lampert had no time for staff who did not see things his way. Mr. Lampert wanted his management team to agree with him – to confirm his Beliefs, Interpretations, Assumptions and Strategies — to believe his BIAS. By seeking managers who would confirm his views, and execute, rather than disagree Mr. Lampert had no one offering alternative data, interpretations, strategies or tactics. And, as Mr. Lampert’s plans kept faltering it led to a revolving door of managers. Leaders came and went in a year or two, blamed for failures that originated at the Chairman’s doorstep. By forcing agreement, rather than disagreement and dialogue, Sears lacked options or alternatives, and the company had no chance of turning around.

4 – Holding assets too long. In 2004 Sears had a LOT of assets. Many that could likely be redeployed at a gain for shareholders. Sears had many owned and leased store locations that were highly valuable with real estate prices climbing from then through 2008. But Mr. Lampert did not spin out that real estate in a REIT, capturing the value for SHLD shareholders while the timing was good. Instead he held those assets as real estate in general plummeted, and as retail real estate fell even further as more revenue shifted to e-commerce. By the time he was ready to sell his REIT much of the value was depleted.

Additionally, Sears had great brands in 2004. DieHard batteries, Craftsman tools, Kenmore appliances and Lands End apparel were just 4 household brands that still had high customer appeal and tremendous value. Mr. Lampert could have sold those brands to another retailer (such as selling DieHard to WalMart, for example) as their house brands, capturing that value. Or he could have mass marketd the brand beyond the Sears store to increase sales and value. Or he could have taken one or more brands on-line as a product leader and “category killer” for ecommerce customers. But he did not act on those options, and as Sears and Kmart stores faded, so did these brands – which largely no longer have any value. Had he sold when value was high there were profits to be made for investors.

5 – Hubris – unfailingly believing in oneself regardless the outcomes. In May, 2012 I wrote that Mr. Lampert was the 2nd worst CEO in America and should fire himself. This was not a comment made in jest. His initial plans had all panned out very badly, and he had no strategy for a turnaround. All results, from all programs implemented during his reign as Chairman had ended badly. Yet, despite these terrible numbers Mr. Lampert refused to recognize he was the wrong person in the wrong job. While it wasn’t clear if anyone could turn around the problems at Sears at such a late date, it was clear Mr. Lampert was not the person to do it. If Mr. Lampert had been as self-analytical as he was critical of others he would have long before replaced himself as the leader at Sears. But hubris would not allow him to do this, he remained blind to his own failings and the terrible outcome of a failed company was pretty much sealed.

From $11B valuation and a $92/share stock price at time of merging KMart and Sears, to a $1.6B valuation and a $15/share stock price. A loss of $9.4B (that’s BILLION DOLLARS). That is amazing value destruction. In a world where employees are fired every day for making mistakes that cost $1,000, $100 or even $10 it is a staggering loss created by Mr. Lampert. At the very least we should learn from his mistakes in order to educate better, value creating leaders.

by Adam Hartung | Oct 16, 2015 | Current Affairs, Defend & Extend, In the Swamp, Lifecycle

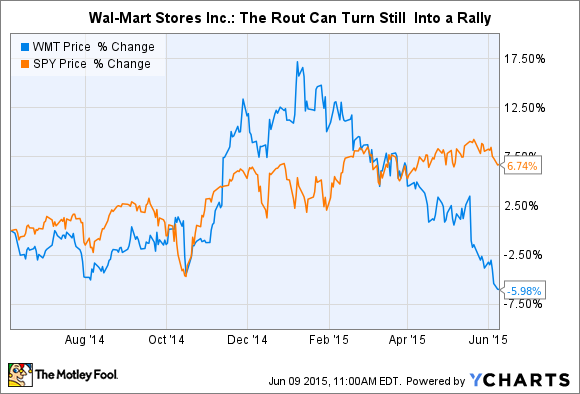

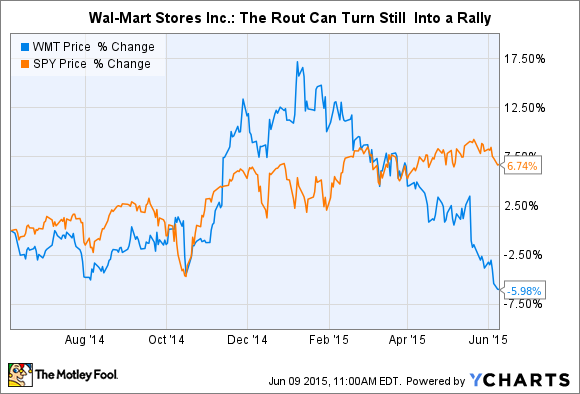

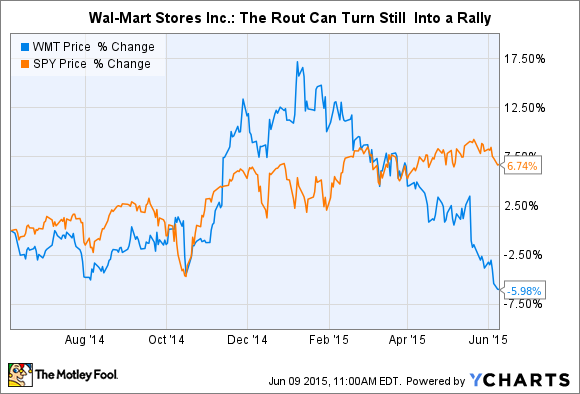

Wal-Mart market value took a huge drop on Wednesday. In fact, the worst valuation decline in its history. That decline continued on Thursday. Since the beginning of 2015 Wal-Mart has lost 1/3 of its value. That is an enormous ouch.

But, if you were surprised, you should not have been. The telltale signs that this was going to happen have been there for years. Like most stock market moves, this one just happened really fast. The “herd behavior” of investors means that most people don’t move until some event happens, and then everyone moves at once carrying out the implications of a sea change in thinking about a company’s future.

But, if you were surprised, you should not have been. The telltale signs that this was going to happen have been there for years. Like most stock market moves, this one just happened really fast. The “herd behavior” of investors means that most people don’t move until some event happens, and then everyone moves at once carrying out the implications of a sea change in thinking about a company’s future.

All the way back in October, 2010 I wrote about “The Wal-Mart Disease.” This is the disease of constantly focusing on improving your “core” business, while market shifts around you increasingly make that “core” less relevant, and less valuable. In the case of Wal-Mart I pointed out that an absolute maniacal focus on retail stores and low-cost operations, in an effort to be the low price retailer, was being made obsolete by on-line retailers who had costs that are a fraction of Wal-Mart’s expensive real estate and armies of employees.

At that time WMT was about $54/share. I recommended nobody own the stock.

In May, 2011 I reiterated this problem at Wal-Mart in a column that paralleled the retailer with software giant Microsoft, and pointed out that because of financial machinations not all earnings are equal. I continued to say that this disease would cripple Wal-Mart. Six months had passed, and the stock was about $55.

By February, 2012 I pointed out that the big reorganization at Wal-Mart was akin to re-arranging deck chairs on a sinking ship and said nobody should own the stock. It was up, however, trading at $61.

At the end of April, 2012 the Wal-Mart Mexican bribery scandal made the press, and I warned investors that this was a telltale sign of a company scrambling to make its numbers – and pushing the ethical (if not legal) envelope in trying to defend and extend its worn out success formula. The stock was $59.

Then in July, 2014 a lawsuit was filed after an overworked Wal-Mart truck driver ran into a car killing James McNair and seriously injuring comedian Tracy Morgan. Again, I pointed out that this was a telltale sign of an organization stretching to try and make money out of a business model that was losing its ability to sustain profits. Market shifts were making it ever harder to keep up with emerging on-line competitors, and accidents like this were visible cracks in the business model. But the stock was now $77. Most investors focused on short-term numbers rather than the telltale signs of distress.

In January, 2015 I pointed out that retail sales were actually down 1% for December, 2014. But Amazon.com had grown considerably. The telltale indication of a rotting traditional retail brick-and-mortar approach was showing itself clearly. Wal-Mart was hitting all time highs of around $87, but I reiterated my recommendation that investors escape the stock.

By July, 2015 we learned that the market cap of Amazon now exceeded that of Wal-Mart. Traditional retail struggles were apparent on several fronts, while on-line growth remained strong. Bigger was not better in the case of Wal-Mart vs. Amazon, because bigger blinded Wal-Mart to the absolute necessity for changing its business model. The stock had fallen back to $72.

Now Wal-Mart is back to $60/share. Where it was in January, 2012 and only 10% higher than when I first said to avoid the stock in 2010. Five years up, then down the roller coaster.

From October of 2010 through January, 2015 I looked dead wrong on Wal-Mart. And the folks who commented on my columns here at this journal and on my web site, or emailed me, were profuse in pointing out that my warnings seemed misguided. Wal-Mart was huge, it was strong and it would dominate was the feedback.

But I kept reiterating the point that long-term investors must look beyond short-term reported sales and earnings. Those numbers are subject to considerable manipulation by management. Further, short-term operating actions, like shorter hours, lower pay, reduced benefits, layoffs and gouging suppliers can all prop up short-term financials at the expense of recognizing the devaluation of the company’s long-term strategy.

Investors buy and hold. They hold until they see telltale signs of a company not adjusting to market shifts. Short-term traders will say you could have bought in 2010, or 2012, and held into 2014, and then jumped out and made a profit. But, who really can do that with forethought? Market timing is a fools game. The herd will always stay too long, then run out too late. Timers get trampled in the stampede more often than book gains.

In this week’s announcement Wal-Mart executives provided more telltale signs of their problems, and the fact that they don’t know how to fix them, and therefore won’t.

- Wal-Mart is going to spend $20B to buy back stock in order to prop up the price. This is the most obvious sign of a company that doesn’t know how to keep up its valuation by growing profits.

- Wal-Mart will spend $11B on sprucing up and opening stores. Really. The demand for retail space has been declining at 4-6%/year for a decade, and retail business growth is all on-line, yet Wal-Mart is still massively investing in its old “core” business.

- Wal-Mart will spend $1.1B on e-commerce. That is the proverbial “drop in the competitors bucket.” Amazon.com alone spent $8.9B in 2014 growing its on-line business.

- Wal-Mart admits profits will decline in the next year. It is planning for a growth stall. Yet, we know that statistically only 7% of companies that have a growth stall ever go on to maintain a consistent growth rate of a mere 2%. In other words, Wal-Mart is projecting the classic “hockey stick” forecast. And investors are to believe it?

The telltale signs of an obsolete business model have been present at Wal-Mart for years, and continue.

In 2003 Sears Holdings was $25/share. In 2004 Sears bought K-Mart, and the stock was $40. I said don’t go near it, as all the signs were bad and the merger was ill-conceived. Despite revenue declines, consistent losses, a revolving door at the executive offices and no sign of any plan to transform the battered, outdated retail giant against growing on-line competition investors believed in CEO Ed Lampert and bid the stock up to $77 in early 2011. (I consistently pointed out the telltale signs of trouble and recommended selling the stock.)

By the end of 2012 it was clear Sears was irrelevant to holiday shoppers, and the stock was trading again at $40. Now, SHLD is $25 – where it was 12 years ago when Mr. Lampert started his machinations. Again, only a market timer could have made money in this company. For long-term investors, the signs were all there that this was not a place to put your money if you want to have capital growth for retirement.

There will be plenty who will call Wal-Mart a “value” stock and recommend investors “buy on weakness.” But Wal-Mart is no value. It is becoming obsolete, irrelevant – increasingly looking like Sears. The likelihood of Wal-Mart falling to $20 (where it was at the beginning of 1998 before it made an 18 month run to $50 more than doubling its value) is far higher than ever trading anywhere near its 2015 highs.

by Adam Hartung | Jul 17, 2015 | Current Affairs, General, In the Swamp, Leadership, Lifecycle

Most analysts, and especially “chartists,” put a lot of emphasis on earnings per share (EPS) and stock price movements when determining whether to buy a stock. Unfortunately, these are not good predictors of company performance, and investors should beware.

Most analysts are focused on short-term, meaning quarter-to-quarter, performance. Their idea of long-term is looking back 1 year, comparing this quarter to same quarter last year. As a result, they fixate on how EPS has done, and will talk about whether improvements in EPS will cause the “multiple” (meaning stock price divided by EPS) will “expand.” They forecast stock price based upon future EPS times the industry multiple. If EPS is growing, they expect the stock to trade at the industry multple, or possibly somewhat better. Grow EPS, hope to grow the multiple, and project a higher valuation.

Analysts will also discuss the “momentum” (meaning direction and volume) of a stock. They look at charts, usually less than one year, and if price is going up they will say the momentum is good for a higher price. They determine the “strength of momentum” by looking at trading volume. Movements up or down on high volume are considered more meaningful than on low volume.

But, unfortunately, these indicators are purely short-term, and are easily manipulated so that they do not reflect the actual performance of the company.

At any given time, a CEO can decide to sell assets and use that cash to buy shares. For example, McDonald’s sold Chipotle and Boston Market. Then leadership took a big chunk of that money and repurchased company shares. That meant McDonalds took its two fastest growing, and highest value, assets and sold them for short-term cash. They traded growth for cash. Then leadership spent that cash to buy shares, rather than invest in in another growth vehicle.

This is where short-term manipulation happens. Say a company is earning $1,000 and has 1,000 shares outstanding, so its EPS is $1. The industry multiple is 10, so the share price is $10. The company sells assets for $1,000 (for purposes of this exercise, let’s assume the book value on those assets is $1,000 so there is no gain, no earnings impact and no tax impact.)

This is where short-term manipulation happens. Say a company is earning $1,000 and has 1,000 shares outstanding, so its EPS is $1. The industry multiple is 10, so the share price is $10. The company sells assets for $1,000 (for purposes of this exercise, let’s assume the book value on those assets is $1,000 so there is no gain, no earnings impact and no tax impact.)

Company leadership says its shares are undervalued, so to help out shareholders it will “return the money to shareholders via a share repurchase” (note, it is not giving money to shareholders, just buying shares. $1,000 buys 100 shares. The number of shares outstanding now falls to 900. Earnings are still $1,000 (flat, no gain,) but dividing $1,000 by 900 now creates an EPS of $1.11 – a greater than 10% gain! Using the same industry multiple, the analysts now say the stock is worth $1.11 x 10 = $11.10!

Even though the company is smaller, and has weaker growth prospects, somehow this “refocusing” of the company on its “core” business and cutting extraneous noise (and growth opportunities) has led to a price increase.

Worse, the company hires a very good investment banker to manage this share repurchase. The investment banker watches stock buys and sells, and any time he sees the stock starting to soften he jumps in and buys some shares, so that momentum remains strong. As time goes by, and the repurchase program is not completed, selectively he will make large purchases on light trading days, thus adding to the stock’s price momentum.

The analysts look at these momentum indicators, now driven by the share repurchase program, and deem the momentum to be strong. “Investors love the stock” the analysts say (even though the marginal investors making the momentum strong are really company management) and start recommending to investors they should anticipate this company achieving a multiple of 11 based on earnings and stock momentum. The price now goes to $1.11 x 11 = $12.21.

Yet the underlying company is no stronger. In fact one could make the case it is weaker. But, due to the higher EPS, better multiple and higher share price the CEO and her team are rewarded with outsized multi-million dollar bonuses.

But, companies the last several years did not even have to sell assets to undertake this kind of manipulation. They could just spend cash from earnings. Earnings have been at record highs, and growing, for several years. Yet most company leaders have not reinvested those earnings in plant, equipment or even people to drive further growth. Instead they have built huge cash hoards, and then spent that cash on share buybacks – creating the EPS/Multiple expansion – and higher valuations – described above.

This has been so successful that in the last quarter untethered corporations have spent $238B on buybacks, while earning only $228B. The short-term benefits are like corporate crack, and companies are spending all the money they have on buybacks rather than reinvesting in growth.

Where does the extra money originate? Many companies have borrowed money to undertake buybacks. Corporate interest rates have been at generational (if not multi-generational) lows for several years. Interest rates were kept low by the Federal Reserve hoping to spur borrowing and reinvestment in new products, plant, etc to drive economic growth, more jobs and higher wages. The goal was to encourage companies to take on more debt, and its associated risk, in order to generate higher future revenues.

Many companies have chosen to borrow money, but rather than investing in growth projects they have bought shares. They borrow money at 2-3%, then buy shares – which can have a much higher immediate impact on valuation – and drive up executive compensation.

This has been wildly prevalent. Since the Fed started its low-interest policy it has added $2.37trillion in cash to the economy. Corporate buybacks have totaled $2.41trillion.

This is why a company can actually have a crummy business, and look ill-positioned for the future, yet have growing EPS and stock price. For example, McDonald’s has gone through rounds of store closures since 2005, sold major assets, now has more stores closing than opening, and has its largest franchisees despondent over future prospects. Yet, the stock has tripled since 2005! Leadership has greatly weakened the company, put it into a growth stall (since 2012,) and yet its value has gone up!

Microsoft has seen its “core” PC market shrink, had terrible new product launches of Vista and Windows 8, wholly failed to succeed with a successful mobile device, written off billions in failed acquisitions, and consistently lost money in its gaming division. Yet, in the last 10 years it has seen EPS grow and its share price double through the power of share buybacks from its enormous cash hoard and ability to grow debt. While it is undoubtedly true that 10 years ago Microsoft was far stronger, as a PC monopolist, than it is today – its value today is now higher.

Share buybacks can go on for several years. Especially in big companies. But they add no value to a company, and if not exceeded by re-investments in growth markets they weaken the company. Long term a company’s value will relate to its ability to grow revenues, and real profits. If a company does not have a viable, competitive business model with real revenue growth prospects, it cannot survive.

Look no further than HP, which has had massive buybacks but is today worth only what it was worth 10 years ago as it prepares to split. Or Sears Holdings which is now worth 15% of its value a decade ago. Short term manipulative actions can fool any investor, and actually artificially keep stock prices high, so make sure you understand the long-term revenue trends, and prospects, of any investment. Regardless of analyst recommendations.

United’s leadership is certainly in a tough place. The airline consistently ranks near the bottom in customer satisfaction, and on-time performance. It has struggled for years with labor strife, and the mechanics union just rejected their proposed contract – again. The flight attendant’s union has been in mediation for months. And few companies have had more consistently bad public relations, as customers have loudly complained about how they are treated – including one fellow making a music and speaking career out of how he was abused by United personnel for months after they destroyed his guitar.

United’s leadership is certainly in a tough place. The airline consistently ranks near the bottom in customer satisfaction, and on-time performance. It has struggled for years with labor strife, and the mechanics union just rejected their proposed contract – again. The flight attendant’s union has been in mediation for months. And few companies have had more consistently bad public relations, as customers have loudly complained about how they are treated – including one fellow making a music and speaking career out of how he was abused by United personnel for months after they destroyed his guitar.

As a case study in bad leadership, Sears under Chairman Lampert offers great lessons in Value Destruction that would serve Professor Fruhan’s teachings well:

As a case study in bad leadership, Sears under Chairman Lampert offers great lessons in Value Destruction that would serve Professor Fruhan’s teachings well: