by Adam Hartung | Oct 26, 2012 | Current Affairs, Defend & Extend, In the Whirlpool, Innovation, Leadership, Web/Tech

This is an exciting time of year for tech users – which is now all of us. The biggest show is the battle between smartphone and tablet leader Apple – which has announced new products with the iPhone 5 and iPad Mini – and the now flailing, old industry leader Microsoft which is trying to re-ignite its sales with a new tablet, operating system and office productivity suite.

I’m reminded of an old joke. Steve the trucker drives with his pal Alex. Someone at the diner says “Steve, imagine you’re going 60 miles an hour when you start down a hill. You keep gaining speed, nearing 90. Then you realize your brakes are out. Now, you see one quarter mile ahead a turn in the road, because there’s a barricade and beyond that a monster cliff. What do you do?”

Steve smiles and says “Well, I wake up Alex.”

“What? Why?” asks the questioner.

“Because Alex has never seen a wreck like the one we’re about to have.”

Microsoft has played “bet the company” on its Windows 8 launch, updated office suite and accompanied Surface tablet. (More on why it didn’t have to do this later.) Now Microsoft has to do something almost never done in business. The company has to overcome a 3 year lateness to market and upend a multi-billion dollar revenue and brand leader. It must overcome two very successful market pioneers, both of which have massive sales, high growth, very good margins, great cash flow and enormous war chests (Apple has over $100B cash.)

Just on the face of it, the daunting task sounds unlikely to succeed.

But there is far more reason to be skeptical. Apple created these markets with new products about which people had few, if any conceptions. But today customers have strong viewpoints on both what a smartphone and tablet should be like to use – and what they expect from Microsoft. And these two viewpoints are almost diametrically opposed.

Yet Microsoft has tried bridging them in the new product – and in doing so guaranteed the products will do poorly. By trying to please everyone Microsoft, like the Ford Edsel, is going to please almost no one:

- Since the initial product viewing, almost all professional reviewers have said the Surface is neat, but not fantastically so. It is different from iOS and Google’s Android products, but not superior. It has generated very little enthusiasm.

- Tests by average users have shown the products to be non-intuitive. Especially when told they are Microsoft products. So the Apple-based interface intuition doesn’t come through for easy use, nor does historical Microsoft experience. Average users have been confused, and realize they now must learn a 3rd interface – the iOS or Android they have, the old Microsoft they have, and now this new thing. It might as well be Linux for all its similarity to Microsoft.

- For those who were excited about having native office products on a tablet, the products aren’t the same as before – in feel or function. And the question becomes, if you really want the office suite do you really want a tablet or should you be using a laptop? The very issue of trying to use Office on the Surface easily makes people rethink the question, and start to realize that they may have said they wanted this, but it really isn’t the big deal they thought it would be. The tablet and laptop have different uses, and between Surface and Win8 they are seeing learning curve cost maybe isn’t worth it.

- The new Win8 – especially on the tablet – does not support a lot of the “professional” applications written on older Windows versions. Those developers now have to redevelop their code for a new platform – and many won’t work on the new tablet processors.

- Many have been banking on Microsoft winning the “enterprise” market. Selling to CIOs who want to preserve legacy code by offering a Microsoft solution. But they run into two problems. (1) Users now have to learn this 3rd, new interface. If they have a Galaxy tab or iPad they will have to carry another device, and learn how to use it. Do not expect happy employees, or executives, who expressly desire avoiding both these ideas. (2) Not all those old applications (drivers, code, etc) will port to the new platform so easily. This is not a “drop in” solution. It will take IT time and money – while CEOs keep asking “why aren’t you doing this for my iPad?”

All of this adds up to a new product set that is very late to market, yet doesn’t offer anything really new. By trying to defend and extend its Windows and Office history, Microsoft missed the market shift. It has spent several billion dollars trying to come up with something that will excite people. But instead of offering something new to change the market, it has given people something old in a new package. Microsoft they pretty much missed the market altogether.

Everyone knows that PC sales are going to decline. Unfortunately, this launch may well accelerate that decline. Remember how slowly people were willing to switch to Vista? How slowly they adopted Microsoft 7 and Office 2010? There are still millions of users running XP – and even Office XP (Office Professional 2003.) These new products may convince customers that the time and effort to “upgrade” simply means its time to switch.

Microsoft has fallen into a classic problem the Dean of innovation Clayton Christensen discusses. Microsoft long ago overshot the user need for PCs and office automation tools. But instead of focusing on developing new solutions – like Apple did by introducing greater mobility with its i products – Microsoft has diligently, for a decade, continued to dump money into overshooting the user needs for its basic products. They can’t admit to themselves that very, very, very few people are looking for a new spreadsheet or word processing application update. Or a new operating system for their laptop.

These new Microsoft products will NOT cause people to quit the trend to mobile devices. They will not change the trend of corporate users supplying their own devices for work (there’s now even an IT acronym for this movement [BYOD,] and a Wikipedia page.) It will not find a ready, excited market of people wanting to learn yet another interface, especially to use old applications they thought they already new!

It did not have to be this way.

Years ago Microsoft started pouring money into xBox. And although investors can complain about the historical cost, the xBox (and Kinect) are now market leaders in the family room. Honestly, Microsoft already has – especially with new products released this week – what people are hoping they can soon buy from AppleTV or GoogleTV; products that are at best vaporware.

Long-term, there is yet another great battle to be fought. What will be the role of monitors, scattered in homes and bars, and in train stations, lobbies and everywhere else? Who will control the access to monitors which will be used for everything from entertainment (video/music,) to research and gaming. The tablet and smartphones may well die, or mutate dramatically, as the ability to connect via monitors located nearly everywhere using —- xBox?

But, this week all discussion of the new xBox Live and music applications were overshadowed by the CEO’s determination to promote the dying product line around Windows8.

This was simply stupid. Ballmer should be fired.

The PC products should be managed for a cash hoarding transition into a smaller market. Investments should be maximized into the new products that support the next market transition. xBox and Kinect should be held up as game changers, and Microsoft should be repositioned as a leader in the family and conference room; an indespensible product line in an ever-more-connected world.

But that didn’t happen this week. And the CEO keeps heading straight for the cliff. Maybe when he takes the truck over the guard rail he’ll finally be replaced. Investors can only wake up and watch – and hope it happens sooner, rather than later.

UPDATE 16 April, 2019 – Android TV is a new emerging tech that could have a big impact on the overall marketplace. Read more about Android TV here.

by Adam Hartung | Oct 4, 2012 | Defend & Extend, In the Whirlpool, Leadership, Lifecycle, Web/Tech

If you're still an investor in Hewlett Packard you must be new to this blog. But for those who remain optimistic, it is worth reveiwing why Ms. Whitman's forecast for HP yesterday won't happen. There are sound reasons why the company has lost 35% of its value since she took over as CEO, over 75% since just 2010 – and over $90B of value from its peak.

HP was dying before Whitman arrived

I recall my father pointing to a large elm tree when I was a boy and saying "that tree will be dead in under 2 years, we might as well cut it down now." "But it's huge, and has leaves" I said. "It doesn't look dead." "It's not dead yet, but the environmental wind damage has cost it too many branches, the changing creek direction created standing water rotting its roots, and neighboring trees have grown taking away its sunshine. That tree simply won't survive. I know it's more than 3 stories tall, with a giant trunk, and you can't tell it now – but it is already dead."

To teach me the lesson, he decided not to cut the tree. And the following spring it barely leafed out. By fall, it was clearly losing bark, and well into demise. We cut it for firewood.

Such is the situation at HP. Before she became CEO (but while she was a Director – so she doesn't escape culpability for the situation) previous leaders made bad decisions that pushed HP in the wrong direction:

- Carly Fiorina, alone, probably killed HP with the single decision to buy Compaq and gut the HP R&D budget to implement a cost-based, generic strategy for competing in Windows-based PCs. She sucked most of the money out of the wildly profitable printer business to subsidize the transition, and destroy any long-term HP value.

- Mark Hurd furthered this disaster by further investing in cost-cutting to promote "scale efficiencies" and price reductions in PCs. Instead of converting software products and data centers into profitable support products for clients shifting to software-as-a-service (SAAS) or cloud services he closed them – to "focus" on the stagnating, profit-eroding PC business.

- His ill-conceived notion of buying EDS to compete in traditional IT services long after the market had demonstrated a major shift offshore, and declining margins, created an $8B write-off last year; almost 60% of the purchase price. Giving HP another big, uncompetitive business unit in a lousy market.

- His purchase of Palm for $1.2B was a ridiculous price for a business that was once an early leader, but had nothing left to offer customers (sort of like RIM today.) HP used Palm to bring out a Touchpad tablet, but it was so late and lacking apps that the product was recalled from retailers after only 49 days. Another write-off.

- Leo Apotheker bought a small Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) software company – only more than a decade after monster competitors Oracle, SAP and IBM had encircled the market. Further, customers are now looking past ERP for alternatives to the inflexible "enterprise apps" which hinder their ability to adjust quickly in today's rapidly changing marektplace. The ERP business is sure to shrink, not grow.

Whitman's "Turnaround Plan" simply won't work

Meg is projecting a classic "hockey stick" performance. She plans for revenues and profits to decline for another year or two, then magically start growing again in 3 years. There's a reason "hockey stick" projections don't happen. They imply the company is going to get a lot better, and competitors won't. And that's not how the world works.

Let's see, what will likely happen over the next 3 years from technology advances by industry leaders Apple, Android and others? They aren't standing still, and there's no reason to believe HP will suddenly develop some fantastic mojo to become a new product innovator, leapfrogging them for new markets.

- Meg's first action is cost cutting – to "fix" HP. Cutting 29,000 additional jobs won't fix anything. It just eliminates a bunch of potentially good idea generators who would like to grow the company. When Meg says this is sure to reduce the number of products, revenues and profits in 2013 we can believe that projection fully.

- Adding features like scanning and copying to printers will make no difference to sales. The proliferation of smart devices increasingly means people don't print. Just like we don't carry newspapers or magazines, we don't want to carry memos or presentations. The world is going digital (duh) and printing demand is not going to grow as we read things on smartphones and tablets instead of paper.

- HP is not going to chase the smartphone business. Although it is growing rapidly. Given how late HP is to market, this is probably not a bad idea. But it begs the question of how HP plans to grow.

- HP is going not going to exit PCs. Too bad. Maybe Lenovo or Dell would pay up for this dying business. Holding onto it will do HP no good, costing even more money when HP tries to remain competitive as sales fall and margins evaporate due to overcapacity leading to price wars.

- HP will launch a Windows8 tablet in January targeted at "enterprises." Given the success of the iPad, Samsung Galaxy and Amazon Kindle products exactly how HP will differentiate for enterprise success is far from clear. And entering the market so late, with an unproven operating system platform is betting the market on Microsoft making it a success. That is far, far from a low-risk bet. We could well see this new tablet about as successful as the ill-fated Touchpad.

- Ms. Whitman is betting HP's future (remember, 3 years from now) on "cloud" computing. Oh boy. That is sort of like when WalMart told us their future growth would be "China." She did not describe what HP was going to do differently, or far superior, to unseat companies already providing a raft of successful, growing, profitable cloud services. "Cloud" is not an untapped market, with companies like Oracle, IBM, VMWare, Salesforce.com, NetApp and EMC (not to mention Apple and Amazon) already well entrenched, investing heavily, launching new products and gathering customers.

HPs problems are far deeper than who is CEO

Ms. Whitman said that the biggest problem at HP has been executive turnover. That is not quite right. The problem is HP has had a string of really TERRIBLE CEOs that have moved the company in the wrong direction, invested horribly in outdated strategies, ignored market shifts and assumed that size alone would keep HP successful. In a bygone era all of them – from Carly Fiorina to Mark Hurd to Leo Apotheker – would have been flogged in the Palo Alto public center then placed in stocks so employees (former and current) could hurl fruit and vegetables, or shout obscenities, at them!

Unfortately, Ms. Whitman is sure to join this ignominious list. Her hockey stick projection will not occur; cannot given her strategy.

HP's only hope is to sell the PC business, radically de-invest in printers and move rapidly into entirely new markets. Like Steve Jobs did a dozen years ago when he cut Mac spending to invest in mobile technologies and transform Apple. Meg's faith in operational improvement, commitment to existing "enterprise" markets and Microsoft technology assures HP, and its investors, a decidedly unpleasant future.

by Adam Hartung | Sep 18, 2012 | Current Affairs, Defend & Extend, Food and Drink, In the Rapids, In the Whirlpool, Innovation, Leadership, Lifecycle

Apple is launching the iPhone 5, and the market cap is hitting record highs. No wonder, what with pre-orders on the Apple site selling out in an hour, and over 2 million units being presold in the first 24 hours after announcement.

We care a lot about Apple, largely because the company has made us all so productive. Instead of chained to PCs with their weight and processor-centric architecture (not to mention problems crashing and corrupting files) while simultaneously carrying limited function cell phones, we all now feel easily interconnected 24×7 from lightweight, always-on smart devices. We feel more productive as we access our work colleagues, work tools, social media or favorite internet sites with ease. We are entertained by music, videos and games at our leisure. And we enjoy the benefits of rapid problem solving – everything from navigation to time management and enterprise demands – with easy to use apps utilizing cloud-based data.

In short, what was a tired, nearly bankrupt Macintosh company has become the leading marketer of innovation that makes our lives remarkably better. So we care – a lot – about the products Apple offers, how it sells them and how much they cost. We want to know how we can apply them to solve even more problems for ourselves, colleagues, customers and suppliers.

Amidst all this hoopla, as you figure out how fast you can buy an iPhone 5 and what to do with your older phone, you very likely forgot that Kraft will be splitting itself into 2 parts in about 2 weeks (October 1). And, most likely, you don't really care.

And you can't imagine why I would even compare Kraft with Apple.

Kraft was once an innovation leader. Velveeta, a much maligned product today, gave Americans a fast, easy solution to cheese sauces that were difficult to make. Instant Mac & Cheese was a meal-in-a-box for people on the run, and at a low budget. Cheeze Whiz offered a ready-to-eat spread for canape's. Individually wrapped American cheese slices solved the problem of sticky product for homemakers putting together lunch sandwiches for school children. Miracle Whip added spice to boring sandwiches. Philadelphia brand cream cheese was a tasty, less fattening alternative to butter while also a great product for sauces.

But, the world changed and these innovations have grown a lot less interesting. Frozen food replaced homemade sauces and boxed solutions. Simultaneously, cooking skills improved. Better options for appetizers emerged than stuffed celery or something on a cracker. School lunches changed, and sandwich alternatives flourished. Across Kraft's product lines, demand changed as new technologies were developed that better fit customers' needs leading to revenue stagnation, margin erosion and an increasing irrelevancy of Kraft in the marketplace – despite its enormous size.

Apple turned itself around by focusing on innovation, becoming the most valuable American publicly traded company. Kraft eschewed innovation for cost cutting, doing more of the same trying to defend its "core," leaving investors with virtually no returns. Meanwhile thousands of Kraft employees have lost their jobs, even though revenues per employee at Kraft are 1/6th those at Apple. And supplier margins are a never-ending cycle of forced reductions as Kraft tries to capture their margin for itself.

Chart Source: Yahoo Finance 18 September, 2012

Apple's value went up because it's revenues went up. In 2007 Apple had #24B in revenues, while Kraft was 150% bigger at $37B. Ending 2011 Apple's revenues, all from organic growth, were up 4x (400%) at $108B. But Kraft's 2011 revenues were only $54B, including roughly $10B of purchased revenues from its Cadbury acquisition, meaning comparative Kraft revenues were $44B; a growth of (ho-hum) 3.5%/year.

Lacking innovation Kraft could not grow the topline, and simply could not grow its value. And paying a premium price for someone else's revenues has led to…. splitting the company in 2 in only 2 years, mystifying everyone as to what sort of strategy the company ever had to grow!

But Kraft's new CEO is not deterred. In an Ad Age interview he promised to ramp up advertising while slashing more jobs to cut costs. As if somehow advertising Velveeta, Miracle Whip, Philadelphia and Mac & Cheese will reverse 30 years of market trends toward different products which better serve customer needs!

Apple spends nearly nothing on advertising. But it does spend on innovation. Innovation adds value. Advertising aging products that solve no new needs does not.

Unfortunately for employees, suppliers and shareholders we can expect Kraft to end up just like Hostess Brands, owner of Wonder Bread and Twinkies, which recently filed bankruptcy due to 40 years of sticking to its core business as the market shifted. Industry leaders know this, as they announced this week they are using Kraft's split to remove the company from the Dow Jones Industrial Average.

Companies that innovate change markets and reap the rewards. By delivering on trends they excite customers who flock to their solutions. Companies that focus on defending and extending their past, especially in times of market shifts, end up failing. Failure may not happen overnight, but it is inevitable.

by Adam Hartung | Aug 9, 2012 | Current Affairs, Defend & Extend, In the Swamp, Leadership, Lock-in

McDonald’s is in a Growth Stall. Even though the stock is less than 10% off its recent 52 week high (which is about the same high it’s had since the start of 2012,) the odds of McDonald’s equity going down are nearly 10x the odds of it achieving new highs.

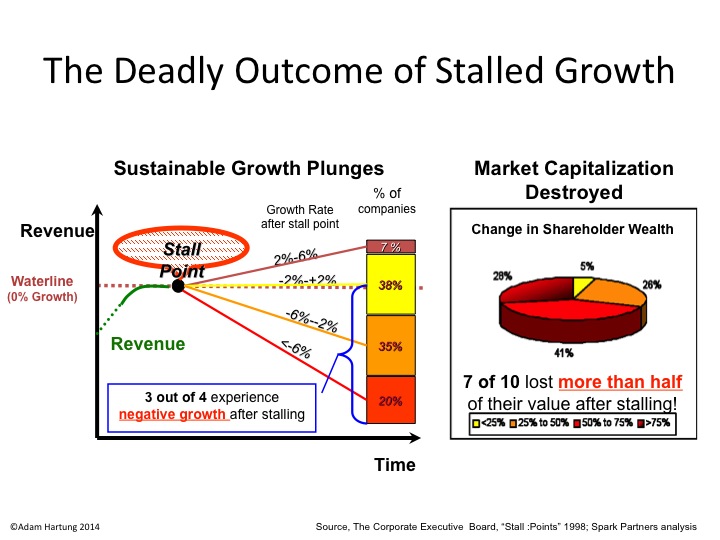

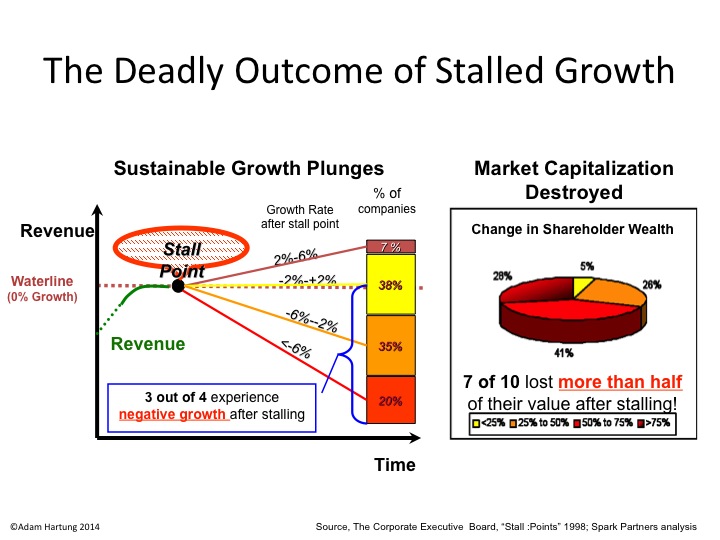

A Growth Stall occurs when a company has 2 consecutive quarters of declining sales or earnings, or 2 consecutive quarters of lower sales or earnings than the previous year. And our research, in conjunction with The Conference Board, proved that when this happens the future becomes fairly easy to predict.

Growth Stalls are Deadly

When companies hit a growth Stall, 93% of the time they are unable to maintain even a 2% growth rate. 55% fall into a consistent revenue decline of more than 2%. 1 in 5 drop into a negative 6%/year revenue slide. 69% of Growth Stalled companies will lose at least half their market capitalization in just a few years. 95% will lose more than 25% of their market value.

Back in February, McDonalds sales in USA stores open at least 13 months fell 1.4%. By May these same stores reported reported their 7th consecutive month (now more than 2 quarters) of declining revenues. And in July McDonald’s reported the worst sales decline in over a decade – with stores globally selling 2.5% less (USA stores were down 3.2% for the month.) McDonald’s leadership is now warning that annual sales will be weaker than forecast – and could well be a reported decline.

While McDonald’s has been saying that Asian store revenue growth had offset the USA declines, we now can see that the USA drop is the key signal of a stall. There was no specific program in Asia to indicate that offshore revenues could create a renewed uptick in USA sales. Now with offshore sales plummeting we can see that McDonald’s American performance is the lead indicator of a company with serious performance issues.

Growth Stalls are a great forecasting tool because they indicate when a company has become “out of step” with its marketplace. While management, and in fact many analysts, will claim that this performance deficit is a short term aberration which will be repaired in coming months, historical evidence — and a plethora of case stories – tell us that in fact by the time a Growth Stall shows itself (especially in a company as large as McDonald’s) the situation is far more dire (and systemic) than management would like investors to believe.

Something fundamental has happened in the marketplace, and company leadership is busy trying to defend its historical business in the face of a major change that is pulling customers toward substitute solutions. Frequently this defend & extend approach exacerbates the problems as retrenchment efforts further hurt revenues.

McDonald’s has reached this inflection point as the result of a long string of leadership decisions which have worked to submarine long-term value.

Back in 2006 McDonald’s sold its fast growing Chipotle chain in order to raise additional funds to close some McDonald’s stores, and undertake an overhaul of the supply chain as well as many remaining stores. This one-time event was initially good for McDonald’s, but it hurt shareholders by letting go of an enormously successful revenue growth machine.

Since that sale Chipotle has outperformed McDonalds by 3x, and it was clear in 2011 that investors were better off with the faster growing Chipotle than the operationally focused McDonald’s. Desperate for revenues as its products lagged changing customer tastes, by December, 2012 McDonald’s was urging franchisees to stay open on Christmas Day in order to add just a bit more to the top line. However, such operational tactics cannot overcome a product line that is fat-and-carb-heavy and off current customer food trends, and by this July was ranked the worst burger in the marketplace. Meanwhile McDonald’s customer service this June ranked dead last in the industry. All telltale signs of the problems creating the emergent Growth Stall.

Meanwhile, McDonald’s is facing a significant attack on its business model as trends turn toward higher minimum wages. By August, 2013 the first signs of the trend were clear – and the impact on McDonald’s long-term fortunes were put in question. By February, 2014 the trend was accelerating, yet McDonald’s continued ignoring the situation. And this month the issue has become a front-and-center problem for McDonald’s investors as the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) has said it will not separate McDonald’s from its franchisees in pay and hours disputes – something which opens McDonald’s deep pockets to litigants looking to build on the living wage trend.

The McDonald’s CEO is somewhat “under seige” due to the poor revenue and earnings reports. Yet, the company continues to ascribe its Growth Stall to short-term problems such as a meat processing scandal in China. But this inverts the real situation. Such scandals are not the cause of current poor results. Rather, they are the outcome of actions taken to meet goals set by leadership pushing too hard, trying to achieve too much, by defending and extending an outdated success formula desperately in need of change to meet new competitive market conditions.

Application of Growth Stall analysis has historically been very valuable. In May, 2009 I reported on the Growth Stall at Motorola which threatened to dramatically lower company value. Subsequently Motorola spun off its money losing phone business, sold other assets and businesses, and is now a very small remnant of the business prior to its Growth Stall; which was brought on by an overwhelming market shift to smartphones from 2-way radios and traditional cell phones.

In February, 2008 a Growth Stall at General Electric indicated the company would struggle to reach historical performance for long-term investors. The stock peaked at $57.80 in 2000, then at $41.40 in July, 2007. By January, 2009 (post Stall) the company had crashed to only $10, and even recent higher valuations ($28 in 10/2013) are still far from the all-time highs – or even highs in the last decade.

In May, 2008 the Growth Stall at AIG portended big problems for the Dow Jones Industrial (DJIA) giant as financial markets continued to shift radically and quickly. By the end of 2008 AIG stock cratered and the company was forced to wipe out shareholders completely in a government-backed restructuring.

Perhaps the most compelling case has been Microsoft. By February, 2010 a Growth Stall was impending (and confirmed by May, 2011) warning of big changes for the tech giant. Mobile device sales exploded, sending Apple and Google stocks soaring, while Microsoft’s primary, core market for PCs (and software for PCs) has fallen into decline. Windows 8 subsequently had a tepid market acceptance, and gained no traction in mobile devices, causing Microsoft to write-off its investment in the Surface tablet. Recent announcements about enormous lay-offs, with vast cuts in the acquired Nokia handheld unit, do not bode well for long-term revenue growth at the decaying (yet cash rich) giant.

As the Dow has surged to record highs, it has lifted all boats. Including those companies which are showing serious problems. It is easy to look at the ubiquity of McDonald’s stores and expect the chain to remain forever dominant. But, the company is facing serious strategic problems with its products, service and business model which leadership has shown no sign of addressing. The recent Growth Stall serves as a key long-term indicator that McDonald’s is facing serious problems which will most likely seriously jeopardize investors’ (as well as employees’, suppliers’ and supporting communities’) potential returns.

by Adam Hartung | Jul 17, 2012 | Current Affairs, Defend & Extend, In the Swamp, Leadership, Lock-in

Most investors shouldn't be. Given demands of work and family, there is almost no time to study companies, markets and select investments. So smaller investors rely on 3rd parties, who rarely perform better than the most common indeces, such as the S&P 500 or Dow Jones Industrial Average. For that reason, few small investors make more than 5-10% per year on their money, and since 2000 many would beg for that much return!

Most investors would make more money with their available time by studying prices on the web and simply buying bargains where they could save more than 10% on their purchase. The satisfaction of a well priced computer, piece of furniture, nice suit or pair of shoes is far more gratifying than earning 2-4% on your investment, while worrying about whether you might LOSE 10-20-30%, or more!

And that's why you don't want to own JPMorganChase (JPMC.) Last week's earning's call was a remarkable example of boredom. Yes, Chairman and CEO Jamie Dimon and his team spent considerable time explaining how the London investment office lost $6B, and why they felt it was an "accident" that would not happen again. But the truth is that this $6B "mistake" wasn't really all that big a deal, compared to the $100B in mortgage and credit card losses since the financial crisis started!

Perhaps Mr. Dimon was right, given JPMC's size, that the whole experience was mostly "a tempest in a teapot." Throughout the call the CEO kept emphasizing that JPMC was "going to go about the business of deposits and lending that is the 'core' business for the bank." Although known for outspokenness, Mr. Dimon sounded like any other bank CEO saying "things happen, but trust us. We really are conservative."

So if a $6B surprise loss isn't that big a deal, what is important to shareholders of JPMC?

How about the unlikelihood of JPMC earning any sort of decent return for the next decade, or two?

The world has changed. But this call, and the mountain of powerpoint slides and documents put out with it, reiterated just how little JPMC (and most of its competition, honestly) has not. In this global world of network relationships, digital transactions, struggling home values and upside down mortgages, and very slow economic growth in developed countries, JPMC has no idea what "the next big thing" will be that could make its investors a 20-30% rate of return.

Yes, in many traditional product lines return-on-equity is in the upper teens or even over 20%. But, then there are losses in others. So lots of trade-offs. Ho-hum. To seek growth JPMC is opening more branches (ho-hum). And trying to sign up more credit card customers (ho-hum) and make more smalll-business loans (ho-hum) while running ads and hoping to accumulate more deposit acounts (ho-hum.) And they have cut compensation and other non-interest costs 12% (ho-hum.)

You could have listened to this call in the 1980s, or 1990s, and it would have sounded the same.

Only the world isn't at all the same.

And Mr. Dimon, and his team, knew this. That's why JPMC created the Chief Investment Office (CIO) in London, and the synthetic credit portfolio that has caused such a stir. The old success formula, despite the bailout which created these highly concentrated, huge banks, simply doesn't have much growth – in revenues or profits. So to jack up returns the bank created an extremely complex business unit that made bets – big bets – sometimes HUGE bets – on interest rates and securities it did not own.

These bets allowed small sums (like, say, $1B) to potentially earn multiples on the investment. Or, lose multiples. And the bets were all based on forecasts about future events – using a computer model created by the CIO's office. As Mr. Dimon's team eloquently pointed out, this model became very complicated, and as reality varied from forecast nobody at JPMC was all that clear why the losses started to happen. As they kept using the model, losses mounted. Oops.

But now, we are to be very assured that JPMC's leaders are paying a lot more attention to the model, and thus JPMC isn't going to have such variations between forecast and reality. So this event won't happen again.

Right.

If JPMC didn't need to use the highly complicated world of derivatives to potentially jack up its returns it would have closed the CIO before these losses happened. Now they claim to have closed the synthetic trading portfolio, but not the CIO. Think about that, if you had a unit operated by one of your very top leaders that "made a mistake" and lost $6B wouldn't you closing it? You would only keep it open if you felt like you had to.

Anybody out there remember the failure of Long Term Capital Management (LTCM?) Certainly Mr. Dimon does. In the 1990s LTCM was the most famous "hedge fund" of its day. The "model" used at Long Term Capital supposedly had zero risk, but extremely high returns. Until a $4B loss created by the default of Russion bonds wiped out all the bank's reserves and capital.

Let's see, what's the big news these days? Oh yeah, possible bond defaults in Greece, Portugal, Spain, Ireland……

The recent "crisis" at JPMC reflects a company locked-in to an antiquated business model which has no growth and declining returns. In order to prop up returns the bank took on almost unquantifiable additional risk, through its hedging operation. Even though hedging long had a risky history, and some spectacular failures.

But this was the only way JPMC knew how to boost returns, so it did it anyway. In an almost off-hand comment Mr. Dimon remarked a capable executive fired CIO Ina Drew was. And that she was credited with "saving the bank" by some of Mr. Dimon's fellow executives. Most likely her money-losing, high risk efforts were another attempt by Ms. Drew to "save the bank's returns" and thus why she was lauded even after losing $6B.

But no more. Now the bank is just going to slog it out being the boring bank it used to be. Amidst all the slides and documents there was NO explanation of what JPMC was going to do next to create growth. So JPMC is still susceptible to crisis – from debt defaults, Euro crisis, no growth economies, etc. – but shows little, if any, upside growth.

And that's why you don't want to invest in JPMC. For the last 3 years the stock has swung wildly. Big swings are loved by betting stock traders. But quarter to quarter vicissitudes are not helpful for investors who need growth so they can generate a 50% gain in 5 years when they need the money for junior's college tuition.

For that matter, I can't think of any "money center" bank worth investing. All of them have the same problem. After being "saved" they are less likely to behave differently than ever before. At JPMC leadership took bets in derivatives trying to jack up returns. At Barclay's Bank it appears leadership manipulated a key lending rate (LIBOR.) All actions typical of executives that are stuck in a lousy market, that is shifting away from them, and feeling it necessary to push the envelope in an effort to squeek out higher returns.

If you feel compelled to invest in financial services, look outside the traditional institutions. Consider Virgin, where Virgin Money is behaving uniquely – and could create incredible growth with very high returns. In a business no "traditional" bank is pursuing. Or Discover Financial Services which is using a unique on-line approach to deposits and lending. Although these are nothing like JPMC, they offer opportunity for growth with probably less risk of another future crisis.

by Adam Hartung | Jul 11, 2012 | Current Affairs, Defend & Extend, Disruptions, Innovation, Leadership, Lock-in

The news is not good for U.S. auto companies. Automakers are resorting to fairly radical promotional programs to spur sales. Chevrolet is offering a 60-day money back guarantee. And Chrysler is offering 90 day delayed financing. Incentives designed to make you want to buy a car, when you really don't want to buy a car. At least, not the cars they are selling.

On the other hand, the barely known, small and far from mainstream Tesla motors gave one of its new Model S cars to Wall Street Journal reviewer Dan Neil, and he gave it a glowing testimonial. He went so far as to compare this 4-door all electric sedan's performance with the Lamborghini and Ford GT supercars. And its design with the Jaguar. And he spent several paragraphs on its comfort, quiet, seating and storage – much more aligned with a Mercedes S series.

There are no manufacturer incentives currently offered on the Tesla Model S.

What's so different about Tesla and GM or Ford? Well, everything. Tesla is a classic case of a disruptive innovator, and GM/Ford are classic examples of old-guard competitors locked into sustaining innovation. While the former is changing the market – like, say Amazon is doing in retail – the latter keeps laughing at them – like, say Wal-Mart, Best Buy, Circuit City and Barnes & Noble have been laughing at Amazon.

Tesla did not set out to be a car company, making a slightly better car. Or a cheaper car. Or an alternative car. Instead it set out to make a superior car.

Its initial approach was a car that offered remarkable 0-60 speed performance, top end speed around 150mph and superior handling. Additionally it looked great in a 2-door European style roadster package. Simply, a wildly better sports car. Oh, and to make this happen they chose to make it all-electric, as well.

It was easy for Detroit automakers to scoff at this effort – and they did. In 2009, while Detroit was reeling and cutting costs – as GM killed off Pontiac, Hummer, Saab and Saturn – the famous Bob Lutz of GM laughed at Tesla and said it really wasn't a car company. Tesla would never really matter because as it grew up it would never compete effectively. According to Mr. Lutz, nobody really wanted an electric car, because it didn't go far enough, it cost too much and the speed/range trade-off made them impractical. Especially at the price Tesla was selling them.

Meanwhile, in 2009 Tesla sold 100% of its production. And opened its second dealership. As manufacturing plants, and dealerships, for the big brands were being closed around the world.

Like all disruptive innovators, Tesla did not make a car for the "mass market." Tesla made a great car, that used a different technology, and met different needs. It was designed for people who wanted a great looking roadster, that handled really well, had really good fuel economy and was quiet. All conditions the electric Tesla met in spades. It wasn't for everyone, but it wasn't designed to be. It was meant to demonstrate a really good car could be made without the traditional trade-offs people like Mr. Lutz said were impossible to overcome.

Now Tesla has a car that is much more aligned with what most people buy. A sedan. But it's nothing like any gasoline (or diesel) powered sedan you could buy. It is much faster, it handles much better, is much roomier, is far quieter, offers an interface more like your tablet and is network connected. It has a range of distance options, from 160 to 300 miles, depending up on buyer preferences and affordability. In short, it is nothing like anything from any traditional car maker – in USA, Japan or Korea.

Again, it is easy for GM to scoff. After all, at $97,000 (for the top-end model) it is a lot more expensive than a gasoline powered Malibu. Or Ford Taurus.

But, it's a fraction of the price of a supercar Ferrari – or even a Porsche Panamera, Mercedes S550, Audi A8, BMW 7 Series, or Jaguar XF or XJ - which are the cars most closely matching size, roominess and performance.

And, it's only about twice as expensive as a loaded Chevy Volt – but with a LOT more advantages. The Model S starts at just over $57,000, which isn't that much more expensive than a $40,000 Volt.

In short, Tesla is demonstrating it CAN change the game in automobiles. While not everybody is ready to spend $100k on a car, and not everyone wants an electric car, Tesla is showing that it can meet unmet needs, emerging needs and expand into more traditional markets with a superior solution for those looking for a new solution. The way, say, Apple did in smartphones compared to RIM.

Why didn't, and can't, GM or Ford do this?

Simply put, they aren't even trying. They are so locked-in to their traditional ideas about what a car should be that they reject the very premise of Tesla. Their assumptions keep them from really trying to do what Tesla has done – and will keep improving – while they keep trying to make the kind of cars, according to all the old specs, they have always done.

Rather than build an electric car, traditionalists denounce the technology. Toyota pioneered the idea of extending a gas car into electric with hybrids – the Prius – which has both a gasoline and an electric engine.

Hmm, no wonder that's more expensive than a similar sized (and performing) gasoline (or diesel) car. And, like most "hybrid" ideas it ends up being a compromise on all accounts. It isn't fast, it doesn't handle particularly well, it isn't all that stylish, or roomy. And there's a debate as to whether the hybrid even recovers its price premium in less than, say, 4 years. And that is all dependent upon gasoline prices.

Ford's approach was so clearly to defend and extend its traditional business that its hybrid line didn't even have its own name! Ford took the existing cars, and reformatted them as hybrids, with the Focus Hybrid, Escape Hybrid and Fusion Hybrid. How is any customer supposed to be excited about a new concept when it is clearly displayed as a trade-off; "gasoline or hybrid, you choose." Hard to have faith in that as a technological leap forward.

And GM gave the market Volt. Although billed as an electric car, it still has a gasoline engine. And again, it has all the traditional trade-offs. High initial price, poor 0-60 performance, poor high-end speed performance, doesn't handle all that well, isn't very stylish and isn't too roomy. The car Tesla-hating Bob Lutz put his personal stamp on. It does achieve high mpg – compared to a gasoline car – if that is your one and only criteria.

Investors are starting to "get it."

There was lots of excitement about auto stocks as 2010 ended. People thought the recession was ending, and auto sales were improving. GM went public at $34/share and rose to about $39. Ford, which cratered to $6/share in July, 2010 tripled to $19 as 2011 started.

But since then, investor enthusiasm has clearly dropped, realizing things haven't changed much in Detroit – if at all. GM and Ford are both down about 50% – roughly $20/share for GM and $9.50/share for Ford.

Meanwhile, in July of 2010 Tesla was about $16/share and has slowly doubled to about $31.50. Why? Because it isn't trying to be Ford, or GM, Toyota, Honda or any other car company. It is emerging as a disruptive alternative that could change customer perspective on what they should expect from their personal transportation.

Like Apple changed perspectives on cell phones. And Amazon did about retail shopping.

Tesla set out to make a better car. It is electric, because the company believes that's how to make a better car. And it is changing the metrics people use when evaluating cars.

Meanwhile, it is practically being unchallenged as the existing competitors – all of which are multiples bigger in revenue, employees, dealers and market cap of Tesla – keep trying to defend their existing business while seeking a low-cost, simple way to extend their product lines. They largely ignore Tesla's Roadster and Model S because those cars don't fit their historical success formula of how you win in automobile competition.

The exact behavior of disruptors, and sustainers likely to fail, as described in The Innovator's Dilemma (Clayton Christensen, HBS Press.)

Choosing to be ignorant is likely to prove very expensive for the shareholders and employees of the traditional auto companies. Why would anybody would ever buy shares in GM or Ford? One went bankrupt, and the other barely avoided it. Like airlines, neither has any idea of how their industry, or their companies, will create long-term growth, or increase shareholder value. For them innovation is defined today like it was in 1960 – by adding "fins" to the old technology. And fins went out of style in the 1960s – about when the value of these companies peaked.

by Adam Hartung | Jul 2, 2012 | Current Affairs, Defend & Extend, In the Whirlpool, Leadership

Cost cutting never improves a company. Period.

We've become so used to reading about reorganizations, layoffs and cost cutting that most people just accept such leadership decisions as "best practice." No matter the company, or industry, it has become conventional wisdom to believe cost cutting is a good thing.

As a reporter recently asked me regarding about layoffs at Yahoo, "Isn't it always smart to cut heads when your profits fall?" Of course not. Have the layoffs at Yahoo in any way made it a better, more successful company able to compete with Google, Microsoft, Facebook and Apple? Given the radical need for innovation, layoffs have only hurt Yahoo more – and made it more likely to end up like RIM (Research in Motion.)

But like believing in a flat world, blood letting to cure disease and that meteorites are spit up out of the ground – this is just another conventional wisdom that is untrue; and desperately needs to be challenged. Cost reductions are killing most companies, not helping them.

Take for example Sara Lee. Sara Lee was once a great, growing company. Its consumer brands were well known, considered premium products and commanded a price premium at retail.

The death spiral at Sara Lee began in 2006. "Professional managers" from top-ranked MBA schools started "improving earnings" with an ongoing program of reorganizations and cost reductions. Largely under the leadership of the much-vaunted Brenda Barnes, none of these cost reductions improved revenues. And the stock price went nowhere.

With each passing year Sara Lee sold parts of the business, such as Hanes, under the disguise of "seeking focus." With each sale a one-time gain was booked, and more people were laid off as the reorganizations continued. Profits remained OK, but the company was actually shrinking – rather than growing.

To prop up the stock price all avaiable cash was used to buy back stock, which helped maximize executive compensation but really did nothing for investors. R&D was eliminated, as was new product development and any new product launches. Instead Sara Lee kept selling more businesses, reorganizing, cutting costs — and buying its own shares. Until finally, after Ms. Barnes left due to an unfortunate stroke, Sara Lee was so small it had nothing left to sell.

So the company decided to split into two parts! Magically, it's like pushing the reset button. What was Sara Lee is now an even smaller Hillshire Brands. All that poor track record of sales, profits and equity value goes POOF as the symbol SLE disappears, and investors are left following HSH – which has only traded for about 2 days! No more looking at that long history of bad performance, it isn't on Bloomberg or Marketwatch or Yahoo. Like the name Sara Lee, the history vanishes.

Well, "if you can't dazzle 'em with brilliance you baffle 'em with bull**it" W.C. Fields once said.

Cost cuts don't work because they don't compound. If I lay off the head of Brand Marketing this year I promise to save $300,000 and improve the Profit & Loss Statement (P&L) by that amount. So a one time improvement. Now – ignoring the fact that the head of branding probably did a number of things to grow revenue – the problem becomes, what do you do the next year? You can't lay off the Brand V.P. again to save that $300,000 twice. Further, if you want to improve the P&L by $450,000 this time you actually have to find 2 Directors to lay off!

Shooting your own troops in order to manage a smaller army rarely wins battles.

Cost cuts are one-time, and are impossible to duplicate. Following this route leads any company toward being much smaller. Like Sara Lee. From a once great company with revenues in the $10s of billions, the new Hillshire Brands isn't even an S&P 500 company (it was replaced by Monster Beverage.) And how can any investor obtain a great return on investment from a company that's shrinking?

What does create a great company? Growth! Unlike cost cutting, if a company launches a new product it can sell $300,000 the first year. If it meets unmet needs, and is a more effective solution, then the product can attract new customers and sell $600,000 the second year. And then $900,000 or maybe $1.2M the third year. (And even add jobs!)

If you are very good at creating and launching products that meet needs, you can create billions of dollars in new revenue. Like Apple with the iPhone and iPad. Or Facebook. Or Groupon. These companies are growing revenues extremely fast because they have products that meet needs. They aren't trying to "save the P&L."

And revenue growth creates "compound returns." Unlike the cost savings which are one time, each dollar of revenue produces cash flow which can be invested in more sales and delivery which can generate even more cash flow. So if growth is 20% and you invest $1,000 in year one, that can become $1,200 in year two, then $1,440 in year three, $1,728 in year four and $2,070 in year five. Each year you receive 20% not only on the $1,000 you invested, but on returns from the previous years!

By compounding year after year, at20% investor money doubles in 5 years. That's why the most important term for investing is CAGR – Compound Annual Growth Rate. Even a small improvement in this number, from say 9% to 11%, has very important meaning. Because it "compounds" year after year. You don't have to add to your investment – merely allowing it to support growth produces very, very handsome returns. The higher the CAGR the better.

Something no cost cutting program can possibly due. Ever.

So, what is the future of Hillshire Brands? According to the CEO, interviewed Sunday for the Chicago Tribune, the company's historically poor performance could be blamed on —– wait —– insufficient focus. Alas, Sara Lee's problem was obviously too much sales! Well, good thing they've been solving that problem.

Of course, having too many brands led to too much lateral thinking and not enough really deep focus on meat. So now that all they need to think about is meat, he expects innovation will be much improved. Right. Now that HSH is a "meat focused meals" company, and the objective is to add innovation to meat, they are considering such radical dietary improvements for our fat-laden, overcaloried American society as adding curry powder to the frozen meatloaf.

Not exactly the iPhone.

To create future growth the first act the new CEO took to push growth was —- wait —– cutting staff by $100million over the next 3 years. Really. He will solve the "analysis paralysis" which seems to concern him as head of this much smaller company because there won't be anyone around to do the analysis, nor to discuss it and certainly not to disagree with the CEO's decisions. Perhaps meat loaf egg rolls will be next.

All reorganizations and cost reductions point to leadership's failure to create growth. Every time. Staff reductions say to investors, employees, suppliers and customers "I have no idea how to add profitable revenue to this company. I really have no clue how to put these people to work productively – even if they are really good people. I have no choice but to cut these jobs, because we desperately need to make the profits look better in order to prop up the stock price short term; even if it kills our chances of developing new products, creating new markets and making superior rates of return for investors long term."

Hillshire's CEO may do very well for himself, and his fellow executives. Assuredly they have compensation plans tied to stock price, and golden parachutes if they leave. HSH is now so small that it is a likely purchase by a more successful company. By further gutting the organization Hillshire's CEO can reduce staff to a minimum, making the acquisition appear easier for a large company. This would allow a premium payment upon acquisition, providing millions to the executives as options pay out and golden parachutes enact.

And it might give a return to the shareholders. If the ongoing slaughter finds a buyer. Otherwise investors will see the stock crater as it heads to bankruptcy. Like RIM and Yahoo. So flip a coin. But that's called gambling, not investing.

What investors need is CAGR. Not cost cutting and reorganizations. And as I've said since 2006 – you don't want to own Sara Lee; even if it's now called Hillshire Brands.

by Adam Hartung | Jun 18, 2012 | Current Affairs, Defend & Extend, In the Whirlpool, Innovation, Leadership, Web/Tech

While there is an appropriately high interest in the Win8 Tablet announcement from Microsoft today, there is no way it is going to be a game changer. Simply because it was never intended to be.

Game changers meet newly emerging, unmet needs, in new ways. People are usually happy enough, until they see the new product/solution and realize "hey, this helps me do something I couldn't do before" or "this helps me solve my problem a lot better." Game changers aren't a simple improvement, they allow customers to do something radically different. And although at first they may well appear to not work too well, or appear too expensive, they meet needs so uniquely, and better, that they cause people to change their behavior.

Motorola invented the smart phone. But Motorola thought it was too expensive to be a cell phone, and not powerful enough to be a PC. Believing it didn't fit existing markets well, Motorola shelved the product.

Apple realized people wanted to be mobile. Cell phones did talk and text OK – and RIM had pretty good email. But it was limited use. Laptops had great use, but were too big, heavy and cumbersome to be really mobile. So Apple figured out how to add apps to the phone, and use cloud services support, in order to make the smart phone fill some pretty useful needs – like navigation, being a flashlight, picking up tweets – and a few hundred thousand other things – like doctors checking x-rays or MRI results. Not as good as a PC, and somewhat on the expensive side for the device and the AT&T connection, but a whole lot more convenient. And that was a game changer.

From the beginning, Windows 8 has been – by design – intended to defend and extend the Windows product line. Rather than designed to resolve unmet needs, or do things nobody else could do, or dramatically improve productivity over all other possible solutions, Windows 8 was designed to simply extend Windows so (hopefully) people would not shift to the game changer technology offered by Apple and later Google.

The problem with trying to extend old products into new markets is it rarely works. Take for example Windows 7. It was designed to replace Windows Vista, which was quite unpopular as an upgrade from Windows XP. By most accounts, Windows 7 is a lot better. But, it didn't offer users anything that that made them excited to buy Windows 7. It didn't solve any unmet needs, or offer any radically better solutions. It was just Windows better and faster (some just said "fixed.")

Nothing wrong with that, except Windows 7 did not address the most critical issue in the personal technology marketplace. Windows 7 did not stop the transition from using PCs to using mobile devices. As a result, while sales of app-enabled smartphones and tablets exploded, sales of PCs stalled:

Chart reproduced with permission of Business Insider Intelligence 6/12/12 courtesy of Alex Cocotas

People are moving to the mobility provided by apps, cloud services and the really easy to use interface on modern mobile devices. Market leading cell phone maker, Nokia, decided it needed to enter smartphones, and did so by wholesale committing to Windows7. But now the CEO, Mr. Elop (formerly a Microsoft executive,) is admitting Windows phones simply don't sell well. Nobody cares about Microsoft, or Windows, now that the game has changed to mobility – and Windows 7 simply doesn't offer the solutions that Apple and Android does. Not even Nokia's massive brand image, distribution or ad spending can help when a product is late, and doesn't greatly exceed the market leader's performance. Just last week Nokia announced it was laying off another 10,000 employees.

Reviews of Win8 have been mixed. And that should not be surprising. Microsoft has made the mistake of trying to make Win8 something nobody really wants. On the one hand it has a new interface called Metro that is supposed to be more iOS/Android "like" by using tiles, touch screen, etc. But it's not a breakthrough, just an effort to be like the existing competition. Maybe a little better, but everyone believes the leaders will be better still with new updates soon. By definition, that is not game changing.

Simultaneously, with Win8 users can find their way into a more historical Windows inteface. But this is not obvious, or intuitive. And it has some pretty "clunky" features for those who like Windows. So it's not a "great" Windows solution that would attract developers today focused on other platforms.

Win8 tries to be the old, and the new, without being great at either, and without offering anything that solves new problems, or creates breakthroughs in simplicity or performance.

Do you know the story about the Ford Edsel?

By focusing on playing catch up, and trying to defend & extend the Windows history, Microsoft missed what was most important about mobility – and that is the thousands of apps. The product line is years late to market, short on apps, short on app developers and short on giving anyone a reason to really create apps for Win8.

Some think it is good if Microsoft makes its own tablet – like it has done with xBox. But that really doesn't matter. What matters is whether Microsoft gives users and developers something that causes them to really, really want a new platform that is late and doesn't have the app base, or the app store, or the interfaces to social media or all the other great thinks they already have come to expect and like about their tablet (or smartphone.)

When iOS came out it was new, unique and had people flocking to buy it. Developers could only be mobile by joining with Apple, and users could only be mobile by buying Apple. That made it a game changer by leading the trend toward mobility.

Google soon joined the competition, built a very large, respectable following by chasing Apple and offering manufacturers an option for competing with Apple.

But Microsoft's new entry gives nobody a reason to develop for, or buy, a Win8 tablet – regardless of who manufactures it. Microsoft does not deliver a huge, untapped market. Microsoft doesn't solve some large, unmet need. Microsoft doesn't promise to change the game to some new, major trend that would drive early adopters to change platforms and bring along the rest of the market.

And making a deal so a dying company, on the edge of bankruptcy – Barnes & Noble – uses your technology is not a "big win." Amazon is killing Barnes & Noble, and Microsoft Windows 8 won't change that. No more than the Nook is going to take out Kindle, Kindle Fire, Galaxy Tab or the iPad. Microsoft can throw away $300million trying to convince people Win8 has value, but spending investor money on a dying businesses as a PR ploy is just stupid.

Microsoft is playing catch up. Catch up with the user interface. Catch up with the format. Catch up with the device size and portability. Catch up with the usability (apps). Just catch up.

Microsoft's problem is that it did not accept the PC market was going to stall back in 2008 or 2009. When it should have seen that mobility was a game changing trend, and required retooling the Microsoft solution suite. Microsoft dabbled with music mobility with Zune, but quickly dropped the effort as it refocused on its "core" Windows. Microsoft dabbled with mobile phones across different solutions including Kin – which it dropped along with Microsoft Mobility. Back again to focusing on operating systems. By maintaining its focus on Windows Microsoft hoped it could stop the trend, and refused to accept the market shift that was destined to stall its sales.

Microsoft stock has been flat for a decade. It's recent value improvement as Win8 approaches launch indicates that hope beats eternally in some investors' breasts for a return of Microsoft software dominance. But those days are long past. PC sales have stalled, and Windows is a product headed toward obsolescence as competitors make ever better, more powerful mobile platforms and ecosystems. If you haven't sold Microsoft yet, this may well be your last chance above $30. Ever.

by Adam Hartung | May 25, 2012 | Defend & Extend, In the Whirlpool, Leadership, Web/Tech

Things are bad at HP these days. CEO and Board changes have confused the management team and investors alike. Despite a heritage based on innovation, the company is now mired in low-growth PC markets with little differentiation. Investors have dumped the stock, dropping company value some 60% over two years, from $52/share to $22 – a loss of about $60billion.

Reacting to the lousy revenue growth prospects as customers shift from PCs to tablets and smartphones, CEO Meg Whitman announced plans to eliminate 27,000 jobs; about 8% of the workforce. This is supposedly the first step in a turnaround of the company that has flailed ever since buying Compaq and changing the company course into head-to-head PC competition a decade ago. But, will it work?

Not a chance.

Fixing HP requires understanding what went wrong at HP. Simply, Carly Fiorina took a company long on innovation and new product development and turned it into the most industrial-era sort of company. Rather than having HP pursue new technologies and products in the development of new markets, like the company had done since its founding creating the market for electronic testing equipment, she plunged HP into a generic manufacturing war.

Pursuing the PC business Ms. Fiorina gave up R&D in favor of adopting the R&D of Microsoft, Intel and others while spending management resources, and money, on cost management. PCs offered no differentiation, and HP was plunged into a gladiator war with Dell, Lenovo and others to make ever cheaper, undifferentiated machines. The strategy was entirely based upon obtaining volume to make money, at a time when anyone could buy manufacturing scale with a phone call to a plethora of Asian suppliers.

Quickly the Board realized this was a cutthroat business primarily requiring supply chain skills, so they dumped Ms. Fiorina in favor of Mr. Hurd. He was relentless in his ability to apply industrial-era tactics at HP, drastically cutting R&D, new product development, marketing and sales as well as fixating on matching the supply chain savings of companies like Dell in manufacturing, and WalMart in retail distribution.

Unfortunately, this strategy was out of date before Ms. Fiorina ever set it in motion. And all Mr. Hurd accomplished was short-term cuts that shored up immediate earnings while sacrificing any opportunities for creating long-term profitable new market development. By the time he was forced out HP had no growth direction. It's PC business fortunes are controlled by its suppliers, and the PC-based printer business is dying. Both primary markets are the victim of a major market shift away from PC use toward mobile devices, where HP has nothing.

HPs commitment to an outdated industrial era supply-side manufacturing strategy can be seen in its acquisitions. What was once the world's leading IT services company, EDS, was bought in 2008 after falling into financial disarray as that market shifted offshore. After HP spent nearly $14B on the purchase, HP used that business to try defending and extending PC product sales, but to little avail. The services group has been downsized regularly as growth evaporated in the face of global trends toward services offshoring and mobile use.

In 2009 HP spent almost $3B on networking gear manufacturer 3Com. But this was after the market had already started shifting to mobile devices and common carriers, leaving a very tough business that even market-leading Cisco has struggled to maintain. Growth again stagnated, and profits evaporated as HP was unable to bring any innovation to the solution set and unable to create any new markets.

In 2010 HP spent $1B on the company that created the hand-held PDA (personal digital assistant) market – the forerunner of our wirelessly connected smartphones – Palm. But that became an enormous fiasco as its WebOS products were late to market, didn't work well and were wholly uncompetitive with superior solutions from Apple and Android suppliers. Again, the industrial-era strategy left HP short on innovation, long on supply chain, and resulted in big write-offs.

Clearly what HP needs is a new strategy. One aligned with the information era in which we live. Think like Apple, which instead of chasing Macs a decade ago shifted into new markets. By creating new products that enhanced mobility Apple came back from the brink of complete failure to spectacular highs. HP needs to learn from this, and pursue an entirely new direction.

But, Meg Whitman is certainly no Steve Jobs. Her career at eBay was far from that of an innovator. eBay rode the growth of internet retailing, but was not Amazon. Rather, instead of focusing on buyers, and what they want, eBay focused on sellers – a classic industrial-era approach. eBay has not been a leader in launching any new technologies (such as Kindle or Fire at Amazon) and has not even been a leader in mobile applications or mobile retail.

While CEO at eBay Ms. Whitman purchased PayPal. But rather than build that platform into the next generation transaction system for web or mobile use, Paypal was used to defend and extend the eBay seller platform. Even though PayPal was the first leader in on-line payments, the market is now crowded with solutions like Google Wallets (Google,) Square (from a Twitter co-founder,) GoPayment (Intuit) and Isis (collection of mobile companies.)

Had Ms. Whitman applied an information-era strategy Paypal could have been a global platform changing the way payment processing is handled. Instead its use and growth has been limited to supporting an historical on-line retail platform. This does not bode well for the future of HP.

HP cannot save its way to prosperity. That never works. Try to think of one turnaround where it did – GM? Tribune Corp? Circuit City? Sears? Best Buy? Kodak? To successfully turn around HP must move – FAST – to innovate new solutions and enter new markets. It must change its strategy to behave a lot more like the company that created the oscilliscope and usher in the electronics age, and a lot less like the industrial-era company it has become – destroying shareholder value along the way.

Is HP so cheap that it's a safe bet. Not hardly. HP is on the same road as DEC, Wang, Lanier, Gateway Computers, Sun Microsystems and Silicon Graphics right now. And that's lousy for investors and employees alike.

by Adam Hartung | May 12, 2012 | Current Affairs, Defend & Extend, In the Swamp, In the Whirlpool, Leadership, Web/Tech

This has been quite the week for CEO mistakes. First was all the hubbub about Scott Thompson, CEO of Yahoo, inflating his resume to include a computer science degree he did not actually receive. According to Mr. Thompson someone at a recruiting firm added that degree claim in 2005, he didn't know it and he's never read his bio since. A simple oversight, if you can believe he hasn't once read his bio in 7 years, and he didn't think it was ever important to correct someone who introduced him or mentioned it. OOPS – the easy answer for someone making several million dollars per year, and trying to guide a very troubled company from the brink of failure. Hopefully he is more persistent about checking company facts.

But luckily for him, his errors were trumped on Thursday when Jamie Dimon, CEO of J.P.MorganChase notified the world that the bank's hedging operation messed up and lost $2B!! OOPS! According to Mr. Dimon this is really no big deal. Which reminded me of the apocryphal Senator Everett Dirksen statement "a billion here, a billion there and pretty soon it all adds up to real money!"

Interesting "little" mistake from a guy who paid himself some $50M a few years ago, and benefitted greatly from the government TARP program. He said this would be "fodder for pundits," as if we all should simply overlook losing $2B? He also said this was "unfortunate timing." As if there's a good time to lose $2B?

But neither of these problems will likely result in the CEOs losing their jobs. As obviously damaging as both mistakes are, which would naturally have caused us mere employees to instantly lose our jobs – and potentially be prosecuted – CEOs are a rare breed who are allowed wide lattitude in their behavior. These are "one off" events that gain a lot of attention, but the media will have forgotten within a few days, and everyone else within a few months.

By comparison, there are at least 5 CEOs that make these 2 mistakes appear pretty small. For these 5, frequently honored for their position, control of resources and personal wealth, they are doing horrific damage to their companies, hurting investors, employees, suppliers and the communities that rely on their organizations. They should have been fired long before this week.

#5 – John Chambers, Cisco Systems. Mr. Chambers is the longest serving CEO on this list, having led Cisco since 1995 and championed much of its rapid growth as corporations around the world began installing networks. Cisco's stock reached $70/share in 2001. But since then a combination of recessions that cut corporate IT budgets and a market shift to cloud computing has left Cisco scrambling for a strategy, and growth.

Mr. Chambers appears to have been great at operating Cisco as long as he was in a growth market. But since customers turned to cloud computing and greater use of mobile telephony networks Cisco has been unable to innovate, launch and grow new markets for cloud storage, services or applications. Mr. Chambers has reorganized the company 3 times – but it has been much like rearranging the deck chairs on the Titanic. Lots of confusion, but no improvement in results.

Between 2001 and 2007 the stock lost half its value, falling to $35. Continuing its slide, since 2007 the stock has halved again, now trading around $17. And there is no sign of new life for Cisco – as each earnings call reinforces a company lacking a strategy in a shifting market. If ever there was a need for replacing a stayed-in-the-job too long CEO it would be Cisco.

#4 – Jeffrey Immelt, General Electric (GE). GE has only had 9 CEOs in its 100+ year life. But this last one has been a doozy. After more than a decade of rapid growth in revenue, profits and valuation under the disruptive "neutron" Jack Welch, GE stock reached $60 in 2000. Which turns out to have been the peak, as GE's value has gone nowhere but down since Mr. Immelt took the top job.

GE was once known for entering and changing markets, unafraid to disrupt how the market performed with innovation in products, supply chain and operations. There was no market too distant, or too locked-in for GE to not find a way to change to its advantage – and profit. But what was the last market we saw GE develop? What has Mr. Immelt, in his decade at the top of GE, done to keep GE as one of the world's most innovative, high growth companies? He has steered the ship away from trouble, but it's only gone in circles as it's used up fuel.

From that high in 2001, GE fell to a low of $8 in 2009 as the financial crisis revealed that under Mr. Immelt GE had largely transitioned from a manufacturing and products company into a financial house. He had taken what was then the easy road to managing money, rather than managing a products and services company. Saved from bankruptcy by a lucrative Berkshire Hathaway, GE lived on. But it's stock is still only $19, down 2/3 from when Mr. Immelt took the CEO position.

"Stewardship" is insufficient leadership in 2012. Today markets shift rapidly, incur intensive global competition and require constant innovation. Mr. Immelt has no vision to propel GE's growth, and should have been gone by 2010, rather than allowed to muddle along with middling performance.

#3 – Mike Duke, WalMart. Mr. Duke has been CEO since 2009, but prior to that he was head of WalMart International. We now know Mr. Duke's business unit saw no problems with bribing foreign officials to grow its business. Just on the basis of knowing about illegal activity, not doing anything about it (and probably condoning and recommending more,) and then trying to change U.S. law to diminish the legal repurcussions, Mr. Duke should have long ago been fired.

It's clear that internally the company and its Board new Mr. Duke was willing to do anything to try and grow WalMart, even if unethical and potentially illegal. Recollections of Enron's Jeff Skilling, Worldcom's Bernie Ebbers and Hollinger's Conrdad Black should be in our heads. How far do we allow leaders to go before holding them accountable?

But worse, not even bribes will save WalMart as Mr. Duke follows a worn-out strategy unfit for competition in 2012. The entire retail market is shifting, with much lower cost on-line companies offering more selection at lower prices. And increasingly these companies are pioneering new technologies to accelerate on-line shopping with easy to use mobile devices, and new apps that make shopping, paying and tracking deliveries easier all the time. But WalMart has largely eschewed the on-line world as its CEO has doggedly sticks with WalMart doing more of the same. That pursuit has limited WalMart's growth, and margins, while the company files further behind competitively.

Unfortunately, WalMart peaked at about $70 in 2000, and has been flat ever since. Investors have gained nothing from this strategy, while employees often work for wages that leave them on the poverty line and without benefits. Scandals across all management layers are embarrassing. Communities find Walmart a mixed bag, initially lowering prices on some goods, but inevitably gutting the local retailers and leaving the community with no local market suppliers. WalMart needs an entirely new strategy to remain viable – and that will not come from Mr. Duke. He should have been gone long before the recent scandal, and surely now.

#2 Edward Lampert, Sears Holdings. OK, Mr. Lampert is the Chairman and not the CEO – but there is no doubt who calls the shots at Sears. And as Mr. Lampert has called the shots, nobody has gained.

Once the most critical force in retailing, since Mr. Lampert took over Sears has become wholly irrelevant. Hoping that Mr. Lampert could make hay out of the vast real estate holdings, and once glorious brands Craftsman, Kenmore and Diehard to turn around the struggling giant, the stock initially took off rising from $30 in 2004 to $170 in 2007 as Jim Cramer of "Mad Money" fame flogged the stock over and over on his rant-a-thon show. But when it was clear results were constantly worsening, as revenues and same-store-sales kept declining, the stock fell out of bed dropping into the $30s in 2009 and again in 2012.

Hope springs eternal in the micro-managing Mr. Lampert. Everyone knows of his personal fortune (#367 on Forbes list of billionaires.) But Mr. Lampert has destroyed Sears. The company may already be so far gone as to be unsavable. The stock price is based upon speculation of asset sales. Mr. Lampert had no idea, from the beginning, how to create value from Sears and he surely should have been gone many months ago as the hyped expectations demonstrably never happened.

#1 – Steve Ballmer, Microsoft. Without a doubt, Mr. Ballmer is the worst CEO of a large publicly traded American company. Not only has he singlehandedly steered Microsoft out of some of the fastest growing and most lucrative tech markets (mobile music, handsets and tablets) but in the process he has sacrificed the growth and profits of not only his company but "ecosystem" companies such as Dell, Hewlett Packard and even Nokia. The reach of his bad leadership has extended far beyond Microsoft when it comes to destroying shareholder value – and jobs.

Microsoft peaked at $60/share in 2000, just as Mr. Ballmer took the reigns. By 2002 it had fallen into the $20s, and has only rarely made it back to its current low $30s value. And no wonder, since execution of new rollouts were constantly delayed, and ended up with products so lacking in any enhanced value that they left customers scrambling to find ways to avoid upgrades. By Mr. Ballmer's own admission Vista had over 200 man-years too much cost, and its launch still, years late, has users avoiding upgrades. Microsoft 7 and Office 2012 did nothing to excite tech users, in corporations or at home, as Apple took the leadership position in personal technology.