by Adam Hartung | Apr 15, 2015 | Defend & Extend, In the Swamp, Leadership

The money is not going into developing any new markets or new products. It is not being used to finance growth of GE at all. Rather, Mr. Immelt will immediately begin a massive $50B stock buyback program in order to prop up the stock price for investors.

When Mr. Immelt took the job of CEO GE sold for about $40/share. Last week it was trading for about $25/share. A decline of 37.5%. During that same time period the Dow Jones Industrial Average, of which GE is the oldest component, rose from 9,600 to 17,900. An increase of 86.5%. This has been a very, very long period of quite unsatisfactory performance for Mr. Immelt.

When Mr. Immelt took the job of CEO GE sold for about $40/share. Last week it was trading for about $25/share. A decline of 37.5%. During that same time period the Dow Jones Industrial Average, of which GE is the oldest component, rose from 9,600 to 17,900. An increase of 86.5%. This has been a very, very long period of quite unsatisfactory performance for Mr. Immelt.

Prior to Mr. Immelt GE was headed by Jack Welch. During his tenure at the top of GE the company created more wealth for its investors than any company ever in the recorded history of U.S. publicly traded companies. GE’s value increased 40-fold (4000%) from 1981 to 2001. He expanded GE into new businesses, often far removed from its industrial manufacturing roots, as market shifts created new opportunities for growing revenues and profits. From what was mostly a diversified manufacturing company Mr. Welch lead GE into real estate as those assets increased in value, then media as advertising revenues skyrocketed and finally financial services as deregulation opened the market for the greatest returns in banking history.

Jack Welch was the Steve Jobs of his era. Because he had the foresight to push GE into new markets, create new products and grow the company. Growth that was so substantial it kept GE constantly in the news, and investors thrilled.

But Mr. Immelt – not so much. During his tenure GE has not developed any new markets. He has not led the company into any growth areas. As the world of portable technology has exploded, making a fortune for Apple and Google investors, GE missed the entire movement into the Internet of Things. Rather than develop new products building on new technologies in wifi, portability, mobility and social Mr. Immelt’s GE sold the appliance division to Electrolux and spent the $3.3B on stock buybacks.

Mr. Immelt’s tenure has been lacked by a complete lack of vision. Rather than looking ahead and preparing for market shifts, Immelt’s GE has reacted to market changes – usually for the poorer. Unprepared for things going off-kilter in financial services, the company was rocked by the financial meltdown and was only saved by an infusion from Berkshire Hathaway. Now it is exiting the business which generates nearly half its profits, claiming it doesn’t want to deal with regulations, rather than figuring out how to make it a more successful enterprise. After accumulating massive real estate holdings, instead of selling them at the peak in the mid-2000s it is now exiting as fast as possible in a recovering economy – to let the fund managers capture gains from improving real estate.

GE is now repatriating some $36B in foreign profits, on which it will pay $6B in taxes. Investors should realize this is happening at the strongest value of the dollar since Mr. Immelt took office. If GE needed these funds, which have been in offshore currencies such as the Euro, it could have repatriated them anytime in the last 3 years and those funds would have been $50B instead of $36B! To say the timing of this transaction could not have been poorer ….

The only thing into which Mr. Immelt has invested has been GE stock. And even that has been a lousy spend, as the price has gone down rather than up! Smart investors have realized that there is no growth in Immelt’s GE, and they have dumped the stock faster than he could buy it. Mr. Immelt’s Harvard MBA gave him insight to financial engineering, but unfortunately not how to lead and grow a major corporation. After 15 years Immelt will leave GE a much smaller, and as he said in the press release, “simpler” business. Apparently it was too big and complicated for him to run.

In the GE statement Mr. Immelt states “This is a major step in our strategy to focus GE around its competitive advantage.” Sorry Mr. Immelt, but that is not a strategy. Identifying growing markets and technologies to create strong, high profit positions with long-term returns is a strategy. Using vague MBA-esque language to hide what is an obvious effort at salvaging a collapsing stock price for another 2 years has nothing to do with strategy. It is a financial tactic.

The Immelt era is the story of a GE which has reacted to events, rather than lead them. Where Steve Jobs took a broken, floundering company and used vision to guide it to great wealth, and Jack Welch used vision to build one of the world’s most resilient and strong corporations, Jeffrey Immelt and his team were overtaken by events at almost every turn. CEO Immelt took what was perhaps the leading corporation of the last century and will leave it in dire shape, lacking a plan for re-establishing its once great heritage. It is a story of utterly failed leadership.

by Adam Hartung | Apr 9, 2015 | Current Affairs, Defend & Extend, Innovation, Leadership

This week a self-driving car built by Delphi of England completed a 9 day trip from San Francisco to New York City. The car traveled 3,400 miles, and was fully automated for 99% of the trip.

Attention has again focused on self-driving cars. There are a handful of players entering the market today, including Apple. But the most famous company by far is Google, which has put over 700,000 autonomous miles on its vehicles since pioneering the concept after winning a DARPA challenge to build a functioning prototype in 2005. In fact, we’re so used to hearing about the Google self-driving car that many of have stopped asking “Why Google? They aren’t in the auto business.”

Of course the idea of a self-driving auto is as old as the Jetson’s (and if you don’t know who the Jetson’s are you are, that was a long time ago.) And nobody should be surprised to hear that prototypes have been on the drawing board for 5 decades. But I bet you didn’t know that DuPont was once seriously engaged in such development.

In 1986 DuPont was America’s largest and most noteworthy chemical company. The company was a pioneer in petrochemicals, and was considered the company that brought the world plastic – at a time when plastic was considered a great, new invention. A leader in films of all sorts, DuPont leadership saw the opportunity for electronics to replace film in applications such as printing (where films were used in high volume for platemaking and proofing) and healthcare (where xRays and MRIs were a large film users.) They conceived of a future time when computers and monitors – digitial products – could replace analog film, and they chose to create a new business unit called Electronic Imaging to pioneer developing these applications.

As the team started they expanded the definition of Electronic Imaging to include all sorts of applications for digital imaging – and using all kinds of technologies. The breadth of analysis, and product development, included non-destructive parts testing, infrared uses such as heads-up displays and inventory identification, and radar applications. Which led the team to using a radar for automating an automobile.

In 1987 DuPont invested in a small company out of San Diego that accomplished something never done before. Using a phased-array radar hooked up to the brakes of a van, they were able to have the car recognize objects in front of the van, calculate in real time the distance between the van and these forward objects, calculate the relative speed of both objects (whether one or both were stationary or moving) and then apply braking in order to maintain a safe distance. If the forward object stopped, then the van would come to a complete stop.

This was all done with discreet componentry, and the team realized future success required developing more specific electronics, including specialized integrated chips that could operate faster and be more error-free. So they drove the prototype from San Diego to Wilmington, DE with a person behind the wheel, but relying as much as possible on the automated system to do all braking. The team collected data on location, speed, weather, traffic conditions, and many other items during the journey and prepared to take the project forward, planning to eventually build a module which could be installed in vehicles as small as cars or as large as 18-wheelers, with enough intelligence to adjust for different vehicle designs and applications (in order to calibrate for different braking distances.)

Net/net they had a working prototype. The product was expected to reduce the number of accidents by assisting drivers with braking. Multi-car pile-ups would become a thing of the past. And this device could potentially allow for better traffic flow because automated braking would reduce – maybe eliminate! – rear-end collisions. This wasn’t a self-driving car, but it was self-braking car, which would be a first step toward the sort of Jetson’s-esque vision the young team imagined.

What happened?

It didn’t take long for the older, “wiser” leadership to shut down the project. Even though several executives participated in a controlled demonstration of the prototype in an enclosed DuPont parking lot, the conclusion was that this project demonstrated just how off-track the new Electronic Imaging Department had become, and that it was clear folks needed to be reigned in and budgets cut:

- This clearly had nothing to do with film or replacing film. DuPont was a chemical company, and to the extent it had any interest in electronics it was where they were applied to potentially cannibalize film sales. Products which were not closely aligned with historical products were simply not to be pursued.

- DuPont had no history in radar, analogue electronics or development of integrated circuits. Yes, DuPont had an Electronics Department, but they sold film for solder masking and other applications of semiconductor and electronics manufacturing. DuPont was a chemical company, not a computer company or electronics company and this division was not going to change this situation.

- This product was seen as carrying too much liability risk. What if it failed? What if the car ran over a child? The auto industry was seen as litigious, and DuPont had no interest in a product that could have the kind of liability this one would generate. Yes, there was an Auto Department, but it sold films for safety glass, plastic sheets used for molding inside panels, and surface coatings which could be painted on the inside and/or outside of the vehicle. But those did not have the kind of failure possibility of this active radar device. [“By the way” the vice-Chairman asked “could that radar fry someone’s innards at a crosswalk?”]

- The market is too limited. Who would really want an automatic braking system? Given what it might cost, only the most expensive cars could install it, and only the wealthiest customers could afford it. This product was destined for niche use, at best, and would never have widespread installation.

Poof, away went the automatic automobile braking project. Once this dagger had been thrown, within just a few months everything that wasn’t printing or medical – in fact anything that wasn’t tied to printing films, xRays and MRI – was gone. Within 2 years leadership decided that for some variant of the 4 issues above the entire Electronic Imaging division was a bad idea. DuPont would be better served if it stuck to its core business, and if it spent money defending and extending film sales rather than trying to cannibalize them.

DuPont liked competing in the oceans where it had long competed. Venturing beyond those oceans was simply too risky. Today, 25 years later, DuPont is about 1/3 the size it was when its leaders launched the ill-fated Electronic Imaging division.

Google obviously has a different way of looking at the opportunity for automating automobile operation. Since winning the DARPA competition Google has spent a goodly sum building and testing ways to automate driving. And it has even gone so far as lobbying to make self-driving cars legal, which they now are in 4 states. Pessimists remain, but every quarter more people are thinking that self-driving cars will be here sooner than we might have imagined. This week’s cross-country achievement fuels speculation that the reality could be just around the corner.

Google seems happy to compete in new oceans. It dominates search, where its share is attacked every day by the likes of Yahoo and Microsoft. But simultaneously Google has invested far outside its core market, including software for PCs (Chrome) and mobile devices (Android), hardware (Nexus phones), media (Blogger, YouTube), payments (Wallet) and even self-driving cars. To what extent these, and dozens of other non-core products/services, will pay off for investors is yet to be determined. But at least Google’s leadership is able to overcome the desire to restrict the company’s options and look for future markets.

Which kind of organization is yours? Do you find reasons to kill new projects, or are you willing to experiment at creating new markets which might create dramatic growth?

by Adam Hartung | Apr 2, 2015 | Current Affairs, Defend & Extend, In the Rapids, Innovation, Leadership, Web/Tech

Microsoft launched its new Surface 3 this week, and it has been gathering rave reviews. Many analysts think its combination of a full Windows OS (not the slimmed down RT version on previous Surface tablets,) thinness and ability to operate as both a tablet and a PC make it a great product for business. And at $499 it is cheaper than any tablet from market pioneer Apple.

Meanwhile Apple keeps promoting the new Apple Watch, which was debuted last month and is scheduled to release April 24. It is a new product in a market segment (wearables) which has had very little development, and very few competitive products. While there is a lot of hoopla, there are also a lot of skeptics who wonder why anyone would buy an Apple Watch. And these skeptics worry Apple’s Watch risks diverting the company’s focus away from profitable tablet sales as competitors hone their offerings.

Looking at these launches gives a lot of insight into how these two companies think, and the way they compete. One clearly lives in red oceans, the other focuses on blue oceans.

Blue Ocean Strategy (Chan Kim and Renee Mauborgne) was released in 2005 by Harvard Business School Press. It became a huge best-seller, and remains popular today. The thesis is that most companies focus on competing against rivals for share in existing markets. Competition intensifies, features blossom, prices decline and the marketplace loses margin as competitors rush to sell cheaper products in order to maintain share. In this competitively intense ocean segments are niched and products are commoditized turning the water red (either the red ink of losses, or the blood of flailing competitors, choose your preferred metaphor.)

On the other hand, companies can choose to avoid this margin-eroding competitive intensity by choosing to put less energy into red oceans, and instead pioneer blue oceans – markets largely untapped by competition. By focusing beyond existing market demands companies can identify unmet needs (needs beyond lower price or incremental product improvements) and then innovate new solutions which create far more profitable uncontested markets – blue oceans.

Obviously, the authors are not big fans of operational excellence and a focus on execution, but instead see more value for shareholders and employees from innovation and new market development.

If we look at the new Surface 3 we see what looks to be a very good product. Certainly a product which is competitive. The Surface 3 has great specifications, a lot of adaptability and meets many user needs – and it is available at what appears to be a favorable price when compared with iPads.

But …. it is being launched into a very, very red ocean.

The market for inexpensive personal computing devices is filled with a lot of products. Don’t forget that before we had tablets we had netbooks. Low cost, scaled back yet very useful Microsoft-based PCs which can be purchased at prices that are less than half the cost of a Surface 3. And although Surface 3 can be used as a tablet, the number of apps is a fraction of competitive iOS and Android products – and the developer community has not yet embraced creating new apps for Windows tablets. So Surface 3 is more than a netbook, but also a lot more expensive.

Additionally, the market has Chromebooks which are low-cost devices using Google Chrome which give most of the capability users need, plus extensive internet/cloud application access at prices less than a third that of Surface 3. In fact, amidst the Microsoft and Apple announcements Google announced it was releasing a new ChromeBit stick which could be plugged into any monitor, then work with any Bluetooth enabled keyboard and mouse, to turn your TV into a computer. And this is expected to sell for as little as $100 – or maybe less!

This is classic red ocean behavior. The market is being fragmented into things that work as PCs, things that work as tablets (meaning run apps instead of applications,) things that deliver the functionality of one or the other but without traditional hardware, and things that are a hybrid of both. And prices are plummeting. Intense competition, multiple suppliers and eroding margins.

Ouch. The “winners” in this market will undoubtedly generate sales. But, will they make decent profits? At low initial prices, and software that is either deeply discounted or free (Google’s cloud-based MSOffice competitive products are free, and buyers of Surface 3 receive 1 year free of MS365 Office in the cloud, as well as free upgrade to Windows 10,) it is far from obvious how profitable these products will be.

Amidst this intense competition for sales of tablets and other low-end devices, Apple seems to be completely focused on selling a product that not many people seem to want. At least not yet. In one of the quirkier product launch messages that’s been used, Apple is saying it developed the Apple Watch because its other innovative product line – the iPhone – “is ruining your life.”

Apple is saying that its leaders have looked into the future, and they think today’s technology is going to move onto our bodies. Become far more personal. More interactive, more knowledgeable about its owner, and more capable of being helpful without being an interruption. They see a future where we don’t need a keyboard, mouse or other artificial interface to connect to technology that improves our productivity.

Right. That is easy to discount. Apple’s leaders are betting on a vision. Not a market. They could be right. Or they could be wrong. They want us to trust them. Meanwhile, if tablet sales falter….. if Surface 3 and ChromeBit do steal the “low end” – or some other segment – of the tablet market…..if smartphone sales slip….. if other “forward looking” products like ApplePay and iBeacon don’t catch on……

This week we see two companies fundamentally different methods of competing. Microsoft thinks in relation to its historical core markets, and engaging in bloody battles to win share. Microsoft looks at existing markets – in this case tablets – and thinks about what it has to do to win sales/share at all cost. Microsoft is a red ocean competitor.

Apple, on the other hand, pioneers new markets. Nobody needed an iPod… folks were happy enough with Sony Walkman and Discman. Everybody loved their Razr phones and Blackberries… until Apple gave them an iPhone and an armload of apps. Netbook sales were skyrocketing until iPads came along providing greater mobility and a different way of getting the job done.

Apple’s success has not been built upon defending historical markets. Rather, it has pioneered new markets that made existing markets obsolete. Its success has never looked obvious. Contrarily, many of its products looked quite underwhelming when launched. Questionable. And it has cannibalized its own products as it brought out new ones (remember when iPods were so new there was the iPod mini, iPod nano and iPod Touch? After 5 years of declining iPod sale Apple has stopped reporting them.) Apple avoids red oceans, and prefers to develop blue ones.

Which company will be more successful in 2020? Time will tell. But, since 2000 Apple has gone from nearly bankrupt to the most valuable publicly traded company in the USA. Since 1/1/2001 Microsoft has gone up 32% in value. Apple has risen 8,000%. While most of us prefer the competition in red oceans, so far Apple has demonstrated what Blue Ocean Strategy authors claimed, that it is more profitable to find blue oceans. And they’ve shown us they can do it.

by Adam Hartung | Mar 27, 2015 | Investing, Mobile, Software, Trends, Web/Tech

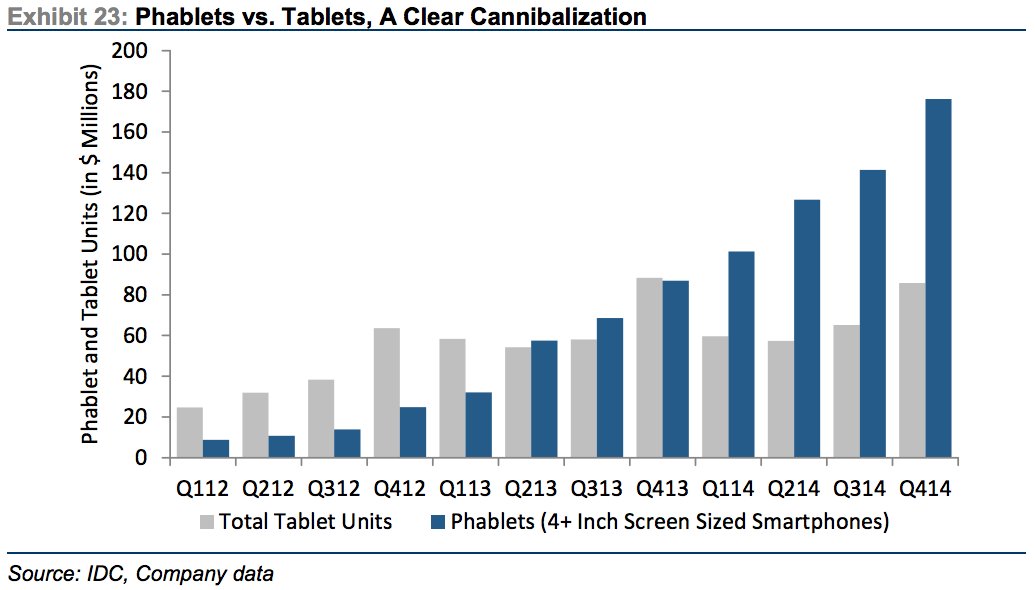

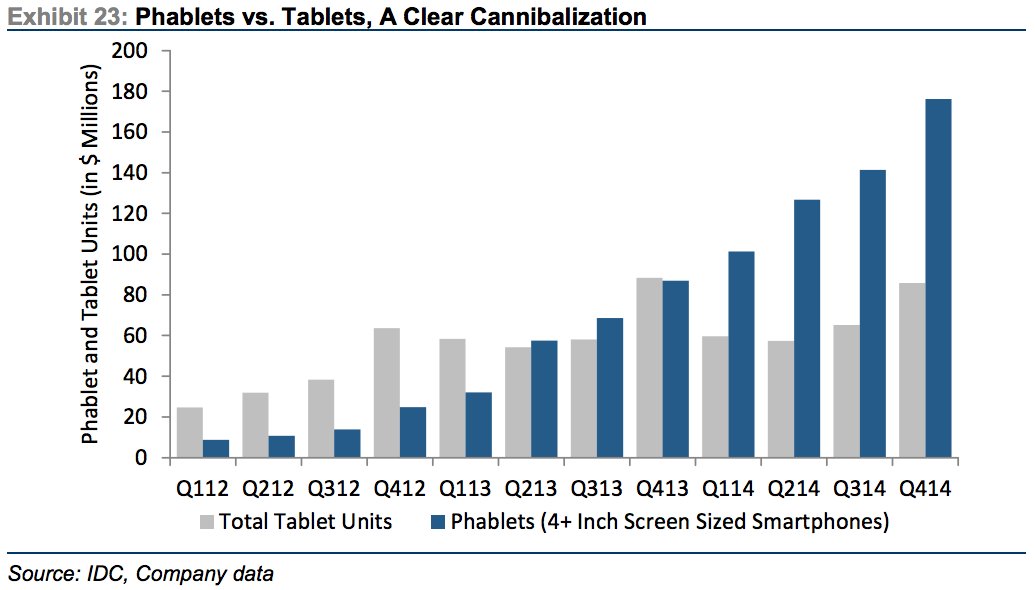

Phablets are a very hot, growing market. Phablets are those huge phones (greater than 4″ screen size) that some people carry around. From almost nothing in 2012, over the last 3 years the market has exploded:

Source: Jay Yarrow, Business Insider http://www.businessinsider.com/in-one-chart-heres-why-the-ipad-business-is-cratering-2015-3?utm_content=&utm_medium=email&utm_source=alerts&nr_email_referer=1

The original creator of this market data, Kulbinder Garcha of Credit Suisse, thinks this demonstrates cannibalization of tablet sales by phablets. And this is supposedly a bad thing for Apple.

But there is another way to look at this. By introducing and promoting a phablet (iPhone 6+ and Galaxy S6,) Apple and Samsung are growing users of mobile media and mobile apps. As the chart shows, growth in tablet sales was nothing compared to what happened when phablets came along. So people who didn’t buy a tablet, and maybe (likely?) wouldn’t, are buying phablets. The market is growing faster with phablets than had they not been introduced, and even if tablet sales shrink Apple and Samsung see revenues continue growing.

Who wins as phablet sales grow? Those who have phablet products in the market, and newer versions in the works.

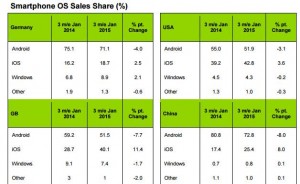

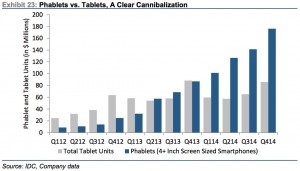

Source: Kantar WorldPanel and Seeking Alpha http://seekingalpha.com/article/3032926-microsoft-the-china-mobile-backed-lenovo-windows-10-smartphone-could-be-a-future-tailwind?ifp=0

As this chart shows, the companies who dominate smartphone sales are those who make Android-based products (#1 is Samsung) and Apple. Microsoft missed the mobile/smartphone trend, and even though it purchased Nokia it has never obtained anything close to double digit share in any market.

Unfortunately for Microsoft enthusiasts, and investors, Microsoft’s Windows10 product is focused first on laptop (PC) users, second on hybrid (products used as both a laptop and tablet), third tablets (primarily the slow-selling Microsoft Surface) and in a far, far trailing position smartphones.

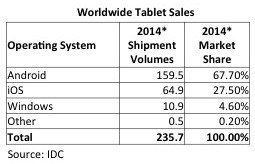

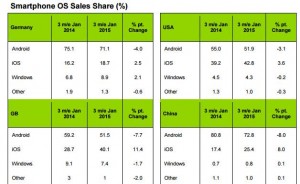

Source: IDC

As data from IDC shows, Surface sales are inconsequential. So the big loser from phablet cannibalization of tablets will be Microsoft. Given its very small user base, and the heavy losses Microsoft has taken on Surface, there is little revenue or cash flow to support an intense competitive effort in a shrinking market. Apple and Samsung will market hard to grow as many sales as possible, and likely will make the tablet products more affordable. Thus one should anticipate Microsoft’s very small tablet share would decline as tablet sales shrink.

This is the problem created when any business misses a major trend.

Microsoft missed the trend to mobile. They didn’t prepare for it in any of their major products, and they let new products, like music player Zune and Lumia phones, languish – and mostly die. By the time Microsoft reacted Apple and Samsung had enormous leads. Microsoft is still trying to play catch-up with its “core” Windows product.

But worse, because it is so far behind, Microsoft’s leaders are unable to forecast where the market will be in 3 years. Consequently they develop products for today’s market, like tablets (and their hybrid products,) which we now see will be obsolete as the market shifts to new products (like phablets.) Because Apple and Samsung already have the new products (phablets) they are prepared to cannibalize the old product sales (tablets) in order to overall grow the marketplace. But Microsoft has no phablet product, really no smartphone product, and will find itself most likely writing off more future Surface products as its tiny market share erodes to nothing.

So this trend to phablets continues to make a Microsoft comeback as a major personal technology competitor problematic. Windows 10 may be coming, but its relevance looks increasingly like that of new Blackberry models. There is little reason to care, because the products are years late and poorly positioned for leading edge customers. Further, developers will already be onto new competitive platforms long before the outdated Microsoft products make it to market. Without share you don’t capture developers, without developers you don’t have a robust app market, without apps you don’t capture customers, without customers you can’t build share — and that’s a terrible whirlpool Microsoft is captured within.

Be sure your business keeps its eyes on trends, and does not wait to react. Waiting can turn out to be deadly.

by Adam Hartung | Mar 23, 2015 | Current Affairs

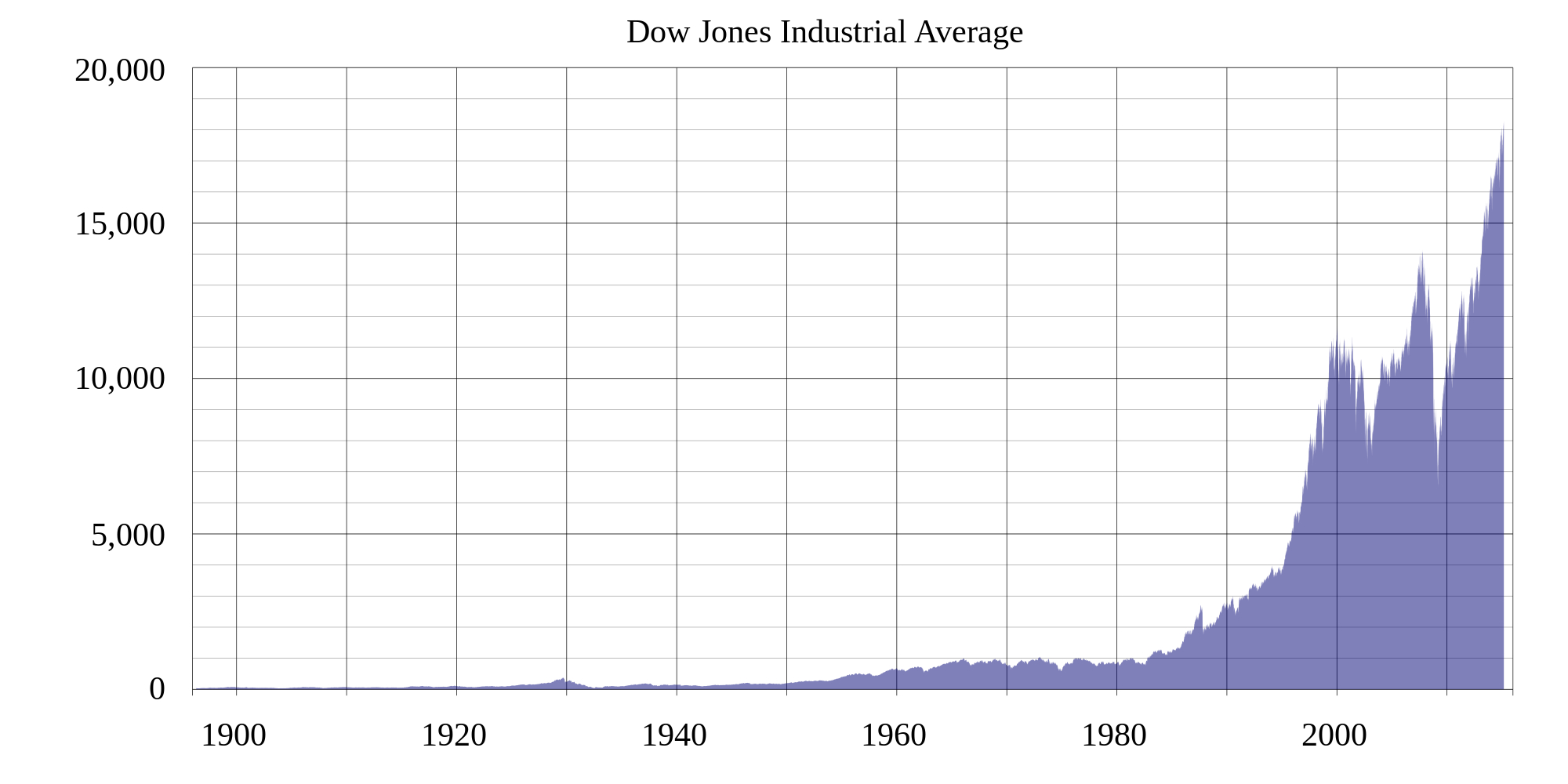

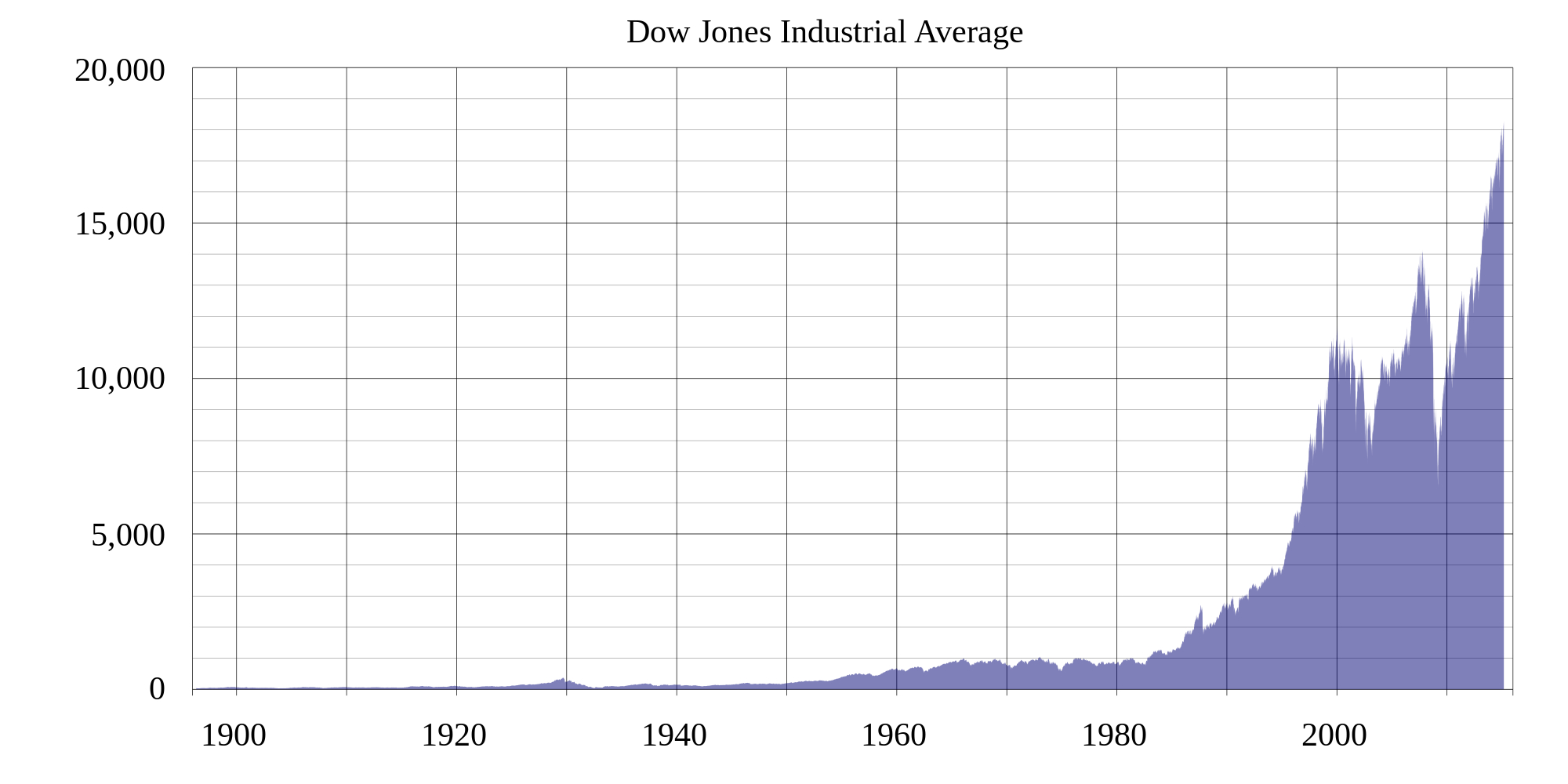

The Dow Jones Industrial Average has been around for about 100 years. It is 30 of the largest market capitalization companies in the USA.

Lots of people think “the Dow,” as it is often called, is the value of the market. This is pretty far from correct, as there are literally thousands of stocks traded on the NYSE and NASDAQ. Better gauges of the overall market would be the NYSE Composite, or the NASDAQ composite. Or even the Wilshire 5000. These much larger data sets are better reflections of the overall stock market.

Some investors, especially small investors or those with little financial training, confuse “the Dow” with the S&P 500. The latter is simply the 500 largest public companies reviewed and evaluated for credit worthiness by Standard & Poors. Obviously, with 500 stocks it is 14 times broader than “the Dow.” So many would say it is a better market indicator than the DJIA.

Yet, lots of people refer to the DJIA, with little understanding of how it is created – and what it really means.

Simply put, the founder of Dow Jones and Company wrote a series of articles form about 1880 to 1900 on investing and stocks. After his death, editors at Dow Jones thought it would be good to consolidate his thoughts into an investing theory, which they called the Dow Theory.

Simply put, they developed three indices based upon a subset of stocks. One was an index of industrial companies, which were largely in commodities like coal, cotton, sugar and tobacco. The second was an index of transportation companies (called the Dow Transports) which was initially loaded with railroads and ocean shippers. The third were the emerging utility companies (Dow Utilities) which were gas distributors and electricity generation/distribution companies.

The Dow Theory was to watch these 3 indices. If two started to move in tandem, up or down, then this was considered an indicator of where the overall market would move in short order. If all 3 move together then it was considered a very strong bullish, or bearish, sign. Dow Theory was the first effort at predicting future stock movements.

After 100 years of academic research, not a lot of people use Dow Theory any longer. It has been replaced with 1,001 different approaches to predicting stock movement. And as other approaches have been created, the Dow Transports and the Dow Utilities are largely forgotten.

But the DJIA still carries a lot of attention. It has changed dramatically over time. The editors at Dow Jones (publisher of the Wall Street Journal and other business publications) review the list and update it. After WWII they determined that Industrials were better represented by steel companies, auto companies and other large manufacturers. Thus they dropped older commodity companies, just as their shares declined, and added companies like GM.

As the economy changed over time, many changes were made to the DJIA. As financial services grew, big banks were added. As retail grew, huge retailers and consumer goods companies were added. As pharmaceuticals grew, they were added. As computer tech grew, large tech companies were added. Each time someone was added, someone was dropped. The only company from the original list is GE.

“The Dow” was continuously “rebalanced.” Thus, even though many companies that were once on the Dow are now completely gone, and many others are in bad shape. Former DJIA companies include: Kodak, Sears, Woolworths, International Harvester, General Motors, Chrysler, Johns-Manville, General Foods, National Steel, Loew’s Theatres.

Thus, the DJIA has had a great upward run for over 100 years. Because it isn’t “the market.” Rather, it is a handful of stocks selected by some of the very top leaders in business. These leaders constantly look to keep the index in growth sectors, while eliminating declining sectors. And removing companies that do really badly – like GM, which filed bankruptcy. In other words, this is an index of the very largest – and some would say safest – companies in America that have a growth capability.

Which is why it is so hard for individual investors – and even pros – to outperform the DJIA. While they tinker around with investments in individual “hot” stocks, and shorting “losers,” overall they rarely can do as well as the DJIA. For all their rebalancing and predicting, only 1 in 4 (or 1 in 5) beat the DJIA in the short term. Long term, only 2 out 2,862 funds have consistently beat the DJIA.

So, by adding Apple the editors are again setting up the DJIA for future growth. AT&T was removed, for the second time. In 2004 it was taken out as AT&T faced bankruptcy. Southwestern Bell bought the AT&T name, and it was added back again. Now it is gone – probably for good – because telecom simply doesn’t have the growth of other sectors like mobile devices.

This is one of the few investment opportunities where “the little guy” gets a tremendous break. Anyone can buy the DJIA. By purchasing Diamonds (Symbol DIA) anyone can buy the DJIA index. You don’t have to do any individual stock buys, nor track changes and do rebalancing. You don’t even have to deal with stock dividends, splits, etc. because the pros will do all of that for you. And, you can buy Diamonds via a low cost on-line broker like e-Trade or ScotTrade and your transaction costs are minimal – less than what you’d pay a mutual fund manager (who is unlikely to do as well as your Diamonds.)

I think most investors are fools to try timing the market. Most people have jobs far removed from financial services and analyzing companies. Even more people have little academic training in how to analyze financial statements, company reports, projections and market opportunities. Heck, if the pros who do this full time can’t beat the DJIA, do most of us have any chance at all?

The DJIA has had a great run the last several years. Investing in the DJIA has outperformed about all other investments, with the best growth rate compared to highly cyclical commodities like gold, or real estate and certainly bonds. And because it isn’t “the market,” but rather a carefully selected basket of large cap stocks, it offers investors the greatest probability of long-term gains with least risk and volatility.

Adding Apple to the DJIA shows that the folks at Dow Jones are keeping their eyes on the proverbial ball. It should encourage investors. And, if you want to share in the growth of equities without having to spend all your free time doing research – or paying high fees – simply buying DIA is a great option.

by Adam Hartung | Mar 10, 2015 | Current Affairs, Defend & Extend, Leadership, Lock-in

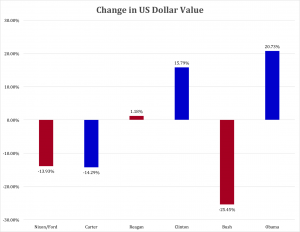

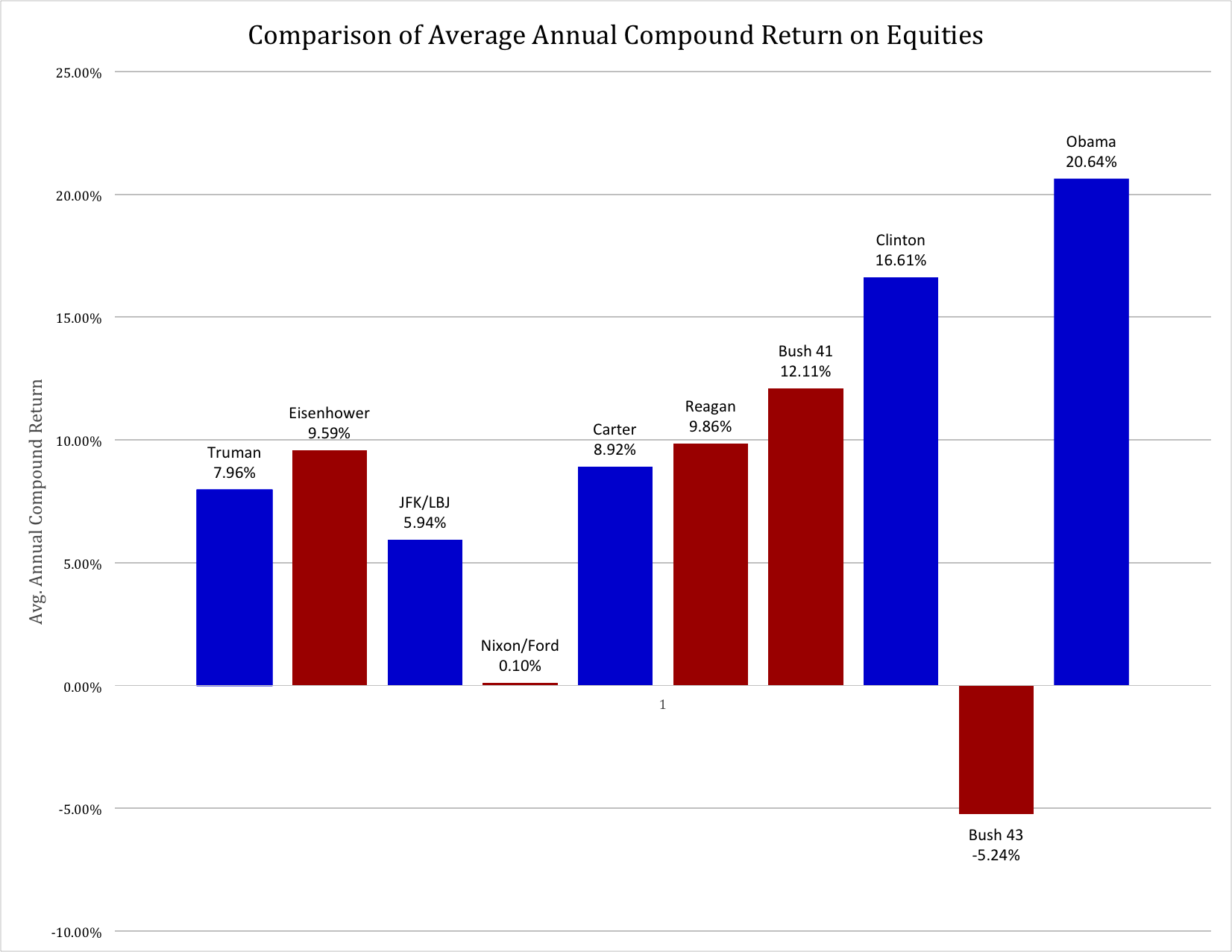

This week marks the 6th anniversary of the stock market’s bull run, with the S&P up 206%. Only 3 other times since WWII have equities had such a prolonged, sustained growth series. Simultaneously, last week saw yet another month with over 200,000 non-farm jobs created, making the current rate of jobs growth the best in 15 years. And, in a move that has taken some by surprise, the U.S. dollar is hitting highs against foreign currencies that have not been seen in over 12 years.

It is a rare economic trifecta, and demonstrates America is doing better than all other developed countries.

It seemed an appropriate time to re-interview Bob Deitrick, Managing Director of Polaris Financial Partners, and author of “Bulls, Bears and the Ballot Box” to obtain his take on the economy. Mr. Deitrick’s book reviewed America’s economic performance under each President since the creation of the Federal Reserve, and in direct opposition to conventional wisdom concluded presidents from the Democratic party were better economic stewards than Republican presidents. When published in 2012 Mr. Deitrick predicted that the economy would continue to do well under President Obama, and so far he’s been proven correct.

AH: Since we discussed “Obama’s Miracle Market” in January, 2014 stocks have continued to rise. Has this bull run surprised you, and do you think it will continue?

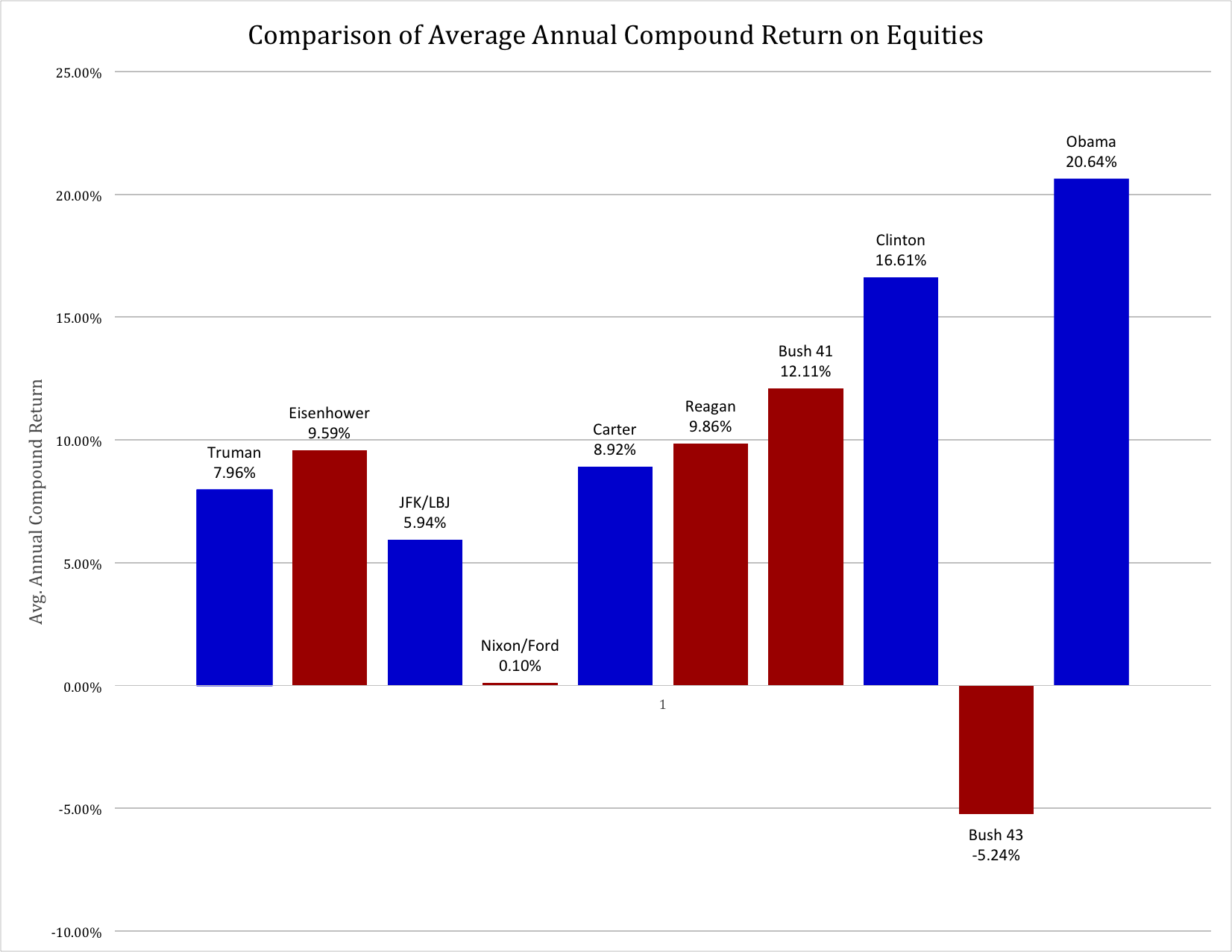

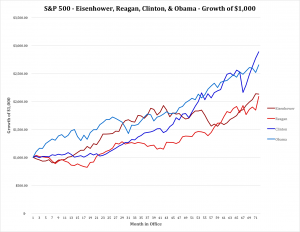

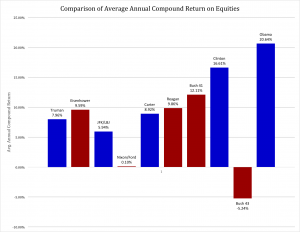

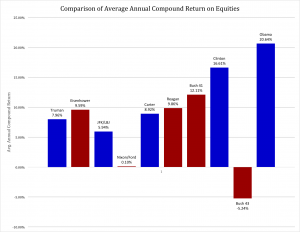

Bob Deitrick: No it has not surprised us. Looking across history since Hoover, Democrats in the White House have generally presided over good stock market gains. Since Clinton was elected, Democratic administrations have done remarkably well, with both Clinton and Obama outperforming the best Republican presidents which were Eisenhower and Reagan.

Looking at the S&P 500, Clinton and Obama have performed about the same with about a 17% annual rate of return through the first 62 months of office. Which is 70% better than the approximate 10% return of Republicans.

It is worth noting that when we take a broader gauge of equities (which we used in the book,) including the more volatile NASDAQ index and the highly selective Dow Jones Industrial Average, then the market’s performance during the Obama administration is unchallenged. The last 6 years generated compound annual returns of 22.5% (including dividend reinvestment) which is the best improvement in equities of all time.

It is also worth noting that the collapse of equities has happened 3 times since 1900, and all under Republican administrations – Hoover, Nixon/Ford, Bush 43. Even Carter had a rising equities market, and the Clinton + Obama years were unparalleled.

We agree with many other analysts that this bull market is not complete. We think the stock markets are only at the half way point in a secular bull cycle which will last, in total, 8 to 12 years.

AH: It was 6 months ago when you pointed out that President Obama outperformed President Reagan on jobs growth. At that time there were many, many naysayers. Yet, August’s numbers were later revised upward to over 200,000 and every month since has continued with strong jobs growth – some nearly 300,000. Are you surprised by the strength in jobs creation, and do you think it will stall?

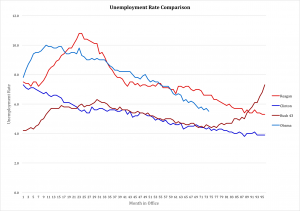

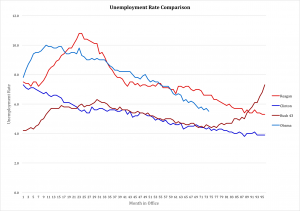

Bob Deitrick: Both Reagan and Obama inherited a bad jobs marketplace. Both of them saw unemployment spike into double digits early in their presidencies. And both created jobs programs that brought down the percentage of people unemployed. Obama had a lesser spike than Reagan, and during the last 5 years unemployment rate fell faster than it did under Reagan.

Both Democrats, Obama and Clinton, had big decreases in unemployment due to their policies. From peak to trough in this current administration unemployment has fallen by 5.5 percentage points, a decline of 81%. Clinton oversaw unemployment decline of 3.1 percentage points, or 73%. Both Democrats followed Bush Republican presidencies which had seen unemployment increase! During Bush 41 unemployment rose by 2 percentage points (5.4% to 7.3%,) and during Bush 43 unemployment nearly doubled from 4.2% to 8.3%. Not even the Carter presidency had unemployment increases anywhere close to the 12 years of Bush presidency.

Both Democrats, Obama and Clinton, had big decreases in unemployment due to their policies. From peak to trough in this current administration unemployment has fallen by 5.5 percentage points, a decline of 81%. Clinton oversaw unemployment decline of 3.1 percentage points, or 73%. Both Democrats followed Bush Republican presidencies which had seen unemployment increase! During Bush 41 unemployment rose by 2 percentage points (5.4% to 7.3%,) and during Bush 43 unemployment nearly doubled from 4.2% to 8.3%. Not even the Carter presidency had unemployment increases anywhere close to the 12 years of Bush presidency.

It is also worth noting that when comparing Obama and Reagan, Reagan undertook the largest increase in non-wartime deficit spending ever. He essentially used a form of “New Deal” debt spending on infrastructure and defense to stimulate jobs production. President Obama has been able to reduce the size of the annual deficit every year since taking office, in reality shrinking the amount of money spent by the government while simultaneously creating these new jobs. The only other president to accomplish this feat was Clinton, who actually balanced the budget during his presidency.

We believe the economy is very strong, and along with other analysts think the jobs recovery will remain intact. With less war spending, lower oil prices, more people covered by insurance, and higher minimum wages consumers will continue to spend and the economy will grow. New technology products will bring more people into the workforce, and manufacturing will continue its renaissance. We expect that unemployment will continue falling toward 4.4% by summer of 2016, returning the economy to non-wartime full employment.

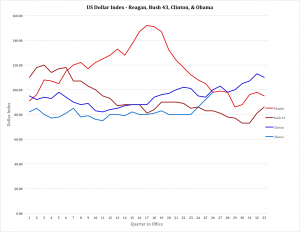

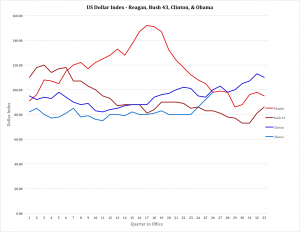

AH: For years many talk show hosts and guests have been declaring that the Fed was flooding the markets with cash and setting the stage for rampant inflation which would ruin the dollar and the U.S. economy. But in the last few months the dollar has rallied to rates we haven’t seen since the 1990s. Did this surprise you, and do you think the dollar will remain strong?

Bob Deitrick: We were not surprised. Ben Bernanke ranks right up there with the first ever Federal Reserve Chairman Marriner Eccles at knowing what to do to keep the American economy from collapsing in the wake of the country’s second depression. Only by re-inflating the economy with more cash, and keeping interest rates low, did America avoid a horrible repeat of the 1930s.

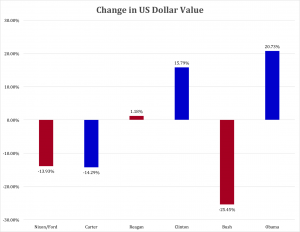

As a result of Democratic policies America re-invested in growth, which allowed companies to invest in plant and equipment and create new jobs, while lowering the deficit. This happened simultaneously with opposite policies being implemented in Europe and Japan (so called “austerity”) which has caused their economies to weaken. And slowed demand from Europe has reduced growth rates in China and India, all leading global investors to return to the U.S. dollar as a safe haven. It is because of our economic strength that the dollar is returning to rates we have not seen since the Clinton presidency.

Many people recall the huge increase in the dollar’s value toward the middle of the Reagan presidency. However, as the U.S. deficits, and total debt, skyrocketed the dollar plummeted. By the time Reagan left office the dollar was worth almost the same as when he entered office.

And the combination of lower taxes plus costs for waging war in the middle east sent the U.S. debt exploding again under Bush 43. What had been a balanced budget under Clinton, which had pushed the dollar almost back to post-war highs, was destroyed causing the dollar to plummet 25%.

The dollar is now up 21% against a basket of world currencies. Given ongoing European weakness and the never-ending fight over austerity we see no reason to think the Euro will make a comeback any time soon. Rather, we predict the strong U.S. economy, especially with oil prices likely to remain low (and priced in dollars,) the U.S. dollar will continue to rally. It could well go back to Clinton-era highs and possibly approach the values during Reagan’s presidency. Should this happen it would be a record improvement in the dollar by any modern administration.

AH: Any concluding comments?

Bob Deitrick: I have voted for both Republicans and Democrats, and think of myself as a centrist. Most people, by definition, are centrists. I long believed that the GOP was the party which was best for the economy. But I could tell something wasn’t adding up during the Bush 43 presidency, so I chose to research the performance of both parties.

The GOP has created an illusion that it is a better economic steward by promoting itself as the party with the better business acumen, frequently touting elected officials from business schools and with MBAs rather than law degrees. The GOP, and the media leaders who identify with the GOP, tell Americans every chance they can that Republicans are the party of financial acuity and have the policies to create economic prowess. Yet we found through our research that these claims were little more than myth. In the modern era, post Great Depression and with a strong Federal Reserve in place, Democratic administrations have been far better stewards of the economy and caretakers of the government’s wallet.

We have coached investors to be in this equity market, and remain long, since early in the Obama administration. We have continued to remain long, and coach investors that in our opinion this remains the best course. We see the economy growing due to a balanced approach to jobs creation, spending and taxation. Were there less partisanship, such as occurred during the Reagan era when the Democrat party controlled the Congress while Republicans controlled the administration, it might be possible for the economy to grow even more quickly.

by Adam Hartung | Mar 9, 2015 | Current Affairs, In the Rapids, Leadership, Television

The Netflix hit series “House of Cards” was released last night. Most media reviewers and analysts are expecting huge numbers of fans will watch the show, given its tremendous popularity the last 2 years. Simultaneously, there are already skeptics who think that releasing all episodes at once “is so last year” when it was a newsworthy event, and no longer will interest viewers, or generate subscribers, as it once did. Coupled with possible subscriber churn, some think that “House of Cards” may have played out its hand.

So, the success of this series may have a measurable impact on the valuation of Netflix. If the “House of Cards” download numbers, which are up to Netflix to report, aren’t what analysts forecast many may scream for the stock to tumble; especially since it is on the verge of reaching new all-time highs. The Netflix price to earnings (P/E) multiple is a lofty 107, and with a valuation of almost $29B it sells for just under 4x sales.

But investors should ignore any, and in fact all, hype about “House of Cards” and whatever analysts say about Netflix. So far, they’ve been wildly wrong when making forecasts about the company. Especially when projecting its demise.

But investors should ignore any, and in fact all, hype about “House of Cards” and whatever analysts say about Netflix. So far, they’ve been wildly wrong when making forecasts about the company. Especially when projecting its demise.

Since Netflix started trading in 2002, it has risen from (all numbers adjusted) $8.5 to $485. That is a whopping 57x increase. That is approximately a 40% compounded rate of return, year after year, for 13 years!

But it has not been a smooth ride. After starting (all numbers rounded for easier reading) at $8.50 in May, 2002 the stock dropped to $3.25 in October – a loss of over 60% in just 5 months. But then it rallied, growing to $38.75, a whopping 12x jump, in just 14 months (1/04!) Only to fall back to $9.80, a 75% loss, by October, 2004 – a mere 9 months later. From there Netflix grew in value by about 5.5x – to $55/share – over the next 5 years (1/10.) When it proceeded to explode in value again, jumping to $295, an almost 6-fold increase, within 18 months (7/11). Only to get creamed, losing almost 80% of its value, back down to $63.85, in the next 4 months (11/11.) The next year it regained some loss, improving in value by 50% to $91.35 (12/12,) only to again explode upward to $445 by February, 2014 a nearly 5-fold increase, in 14 months. Two months later, a drop of 25% to $322 (4/14). But then in 4 months back up to $440 (8/14), and back down 4 months later to $341 (12/14) only to approach new highs reaching $480 last week – just 2 months later.

That is the definition of volatility.

Netflix is a disruptive innovator. And, simply put, stock analysts don’t know how to value disruptive innovators. Because their focus is all on historical numbers, and then projecting those historicals forward. As a result, analysts are heavily biased toward expecting incumbents to do well, and simultaneously being highly skeptical of any disruptive company. Disruptors challenge the old order, and invalidate the giant excel models which analysts create. Thus analysts are very prone to saying that incumbents will remain in charge, and that incumbents will overwhelm any smaller company trying to change the industry model. It is their bias, and they use all kinds of historical numbers to explain why the bigger, older company will project forward well, while the smaller, newer company will stumble and be overwhelmed by the entrenched competitor.

And that leads to volatility. As each quarter and year comes along, analysts make radically different assumptions about the business model they don’t understand, which is the disruptor. Constantly changing their assumptions about the newer kid on the block, they make mistake after mistake with their projections and generally caution people not to buy the disruptor’s stock. And, should the disruptor at any time not meet the expectations that these analysts invented, then they scream for shareholders to dump their holdings.

Netflix first competed in distribution of VHS tapes and DVDs. Netflix sent them to people’s homes, with no time limit on how long folks could keep them. This model was radically different from market leader Blockbuster Video, so analysts said Blockbuster would crush Netflix, which would never grow. Wrong. Not only did Blockbuster grow, but it eventually drove Blockbuster into bankruptcy because it was attuned to trends for convenience and shopping from home.

As it entered streaming video, analysts did not understand the model and predicted Netflix would cannibalize its historical, core DVD business thus undermining its own economics. And, further, much larger Amazon would kill Netflix in streaming. Analysts screamed to dump the stock, and folks did. Wrong. Netflix discovered it was a good outlet for syndication, created a huge library of not only movies but television programs, and grew much faster and more profitably than Amazon in streaming.

Then Netflix turned to original programming. Again, analysts said this would be a huge investment that would kill the company’s financials. And besides that people already had original programming from historical market leaders HBO and Showtime. Wrong. By using analysis of what people liked from its archive, Netflix leadership hedged its bets and its original shows, especially “House of Cards” have been big hits that brought in more subscribers. HBO and Showtime, which have depended on cable companies to distribute their programming, are now increasingly becoming additional programming on the Netflix distribution channel.

Investors should own Netflix because the company’s leadership, including CEO Reed Hastings, are great at disruptive innovation. They identify unmet customer needs and then fulfill those needs. Netflix time and again has demonstrated it can figure out a better way to give certain user segments what they want, and then expand their offering to eat away at the traditional market. Once it was retail movie distribution, increasingly it is becoming cable distribution via companies like ComCast, AT&T and Time Warner.

And investors must be long-term. Netflix is an example of why trading is a bad idea – unless you do it for a living. Most of us who have full time day jobs cannot try timing the ups and downs of stock movements. For us, it is better to buy and hold. When you’re ready to buy, buy. Don’t wait, because in the short term there is no way to predict if a stock will go up or down. You have to buy because you are ready to invest, and you expect that over the next 3, 5, 7 years this company will continue to drive growth in revenues and profits, thus expanding its valuation.

Netflix, like Apple, is a company that has mastered the skills of disruptive innovation. While the competition is trying to figure out how to sustain its historical position by doing the same thing better, faster and cheaper Netflix is figuring out “the next big thing” and then delivering it. As the market shifts, Netflix is there delivering on trends with new products – and new business models – which push revenues and profits higher.

That’s why it would have been smart to buy Netflix any time the last 13 years and simply held it. And odds are it will continue to drive higher valuations for investors for many years to come. Not only are HBO, Showtime and Comcast in its sites, but the broadcast networks (ABC, CBS, NBC) are not far behind. It’s a very big media market, which is shifting dramatically, and Netflix is clearly the leader. Not unlike Apple has been in personal technology.

by Adam Hartung | Mar 9, 2015 | Current Affairs, Defend & Extend, In the Whirlpool, Leadership

Best Buy, the venerable electronics retailer, is hitting 52 week highs. Coming off a low of $24 in April, 2014 the current price of about $40 is a 67% increase in just 10 months. Analysts are now cheering investors to own the stock, with Marketwatch pronouncing that the last bearish analyst has thrown in the towel.

If you are a trader, perhaps you want to consider this stock. But if you aren’t an investment professional, and you buy and hold stocks for years, then Best Buy is not a stock you should own.

The bullish case for owning Best Buy is based on recovering sales per store, and recovering earnings, after a reduction in the number of stores, and employees, lowered costs. Further, with Radio Shack now in bankruptcy sales are showing an uptick as customers swing over. And that is expected to continue as Sears closes more stores on its marches toward bankruptcy. Additionally, it is hoped that lower gasoline prices will allow consumers to spend more on electronics and appliances at Best Buy.

But, this completely ignores the trend toward on-line retail sales, and the long-term deleterious impact this trend will have on Best Buy. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, on-line sales as a percent of all retail have grown from less than 2.4% in 2005 to over 7.6% by end of 2014 – more than tripling! But more critical to this discussion, all retail sales includes automobiles, lumber, groceries – lots of things where there is little or no online volume.

As most folks know, the number one category for online sales is computers and consumer electronics, which consistently accounts for about 20% of ALL online retail. In fact, about 25% of all consumer electronics are sold online. So the growth in online retail is disproportionately in the Best Buy wheelhouse. The segment where Best Buy competes against streamlined online retailers such as NewEgg.com, ThinkGeek.com and the ever-dominant Amazon.com.

So while in the short term some traditional retail customers will now shift demand to Best Buy, this is not unlike the revenue “bounce” Best Buy received when Circuit City failed. Short term up, but the long term trend continued hammering away at Best Buy’s core market.

This is a big deal because the marginal economic impact of this shift is horrific to Best Buy. In traditional retail most costs are “fixed,” meaning they can’t be changed much month to month. The cost of real estate, store maintenance, utilities and staff cannot be easily adjusted – unless there is a decision to close a gob of stores. Thus losing even a few sales, what economists call “marginal” sales, wreaks havoc on earnings.

Back in 2010 and 2011 Best Buy made a net income (’12 and ’13 were losses) of about 2.6% – or about $2.60 on every $100 revenue. Cost of Goods sold is about 75% of revenue. So on $100 of revenue, $25 is available to cover fixed costs. If revenue falls by just $10, Best Buy loses $2.50 of margin to cover fixed costs. Remember, however, that the net income is only $2.60. So losing 10% of revenue ($10 out of the $100) means Best Buy loses $2.50 of contribution to fixed costs, and that is deducted from net income of $2.60, leaving Best Buy with a meager 10cents of profitability. A 10% loss of revenue wipes out 96% of profits!

Now you know why retailers who lose even a small part of their sales are suddenly closing stores right and left.

Looking forward, online retail sales are forecast to grow by another 57%, reaching 11% of total retail by 2018. But, as we know, this is disproportionately going to be driven by consumer electronics. Which means that while sales for Best Buy stores are up short term, long term they will plummet. That means there will be more store closings, and layoffs as sales shrink. And, increasingly Best Buy will have to compete head-to-head online against entrenched, leading competitors who have been stealing market share for 10+ years.

If you want to trade on the short-term uptick in revenue, and return to slight profitability, then hold your breath and see if you can outsmart the market by picking the right time, and price, for buying and selling Best Buy. But, if you like to invest in strong companies you expect to grow for another 5 years without having to be a market timer, then avoid Best Buy.

Quite simply, it is never a good idea to bet against a long term trend. Short term aberrations will happen, and it may look like the trend has changed. But the trend to online commerce is picking up steam, not reducing. If you want to invest in retail, you want to invest in those companies that demonstrate they can capture the customer’s revenue in the growing, online marketplace.

by Adam Hartung | Feb 18, 2015 | Current Affairs, Leadership

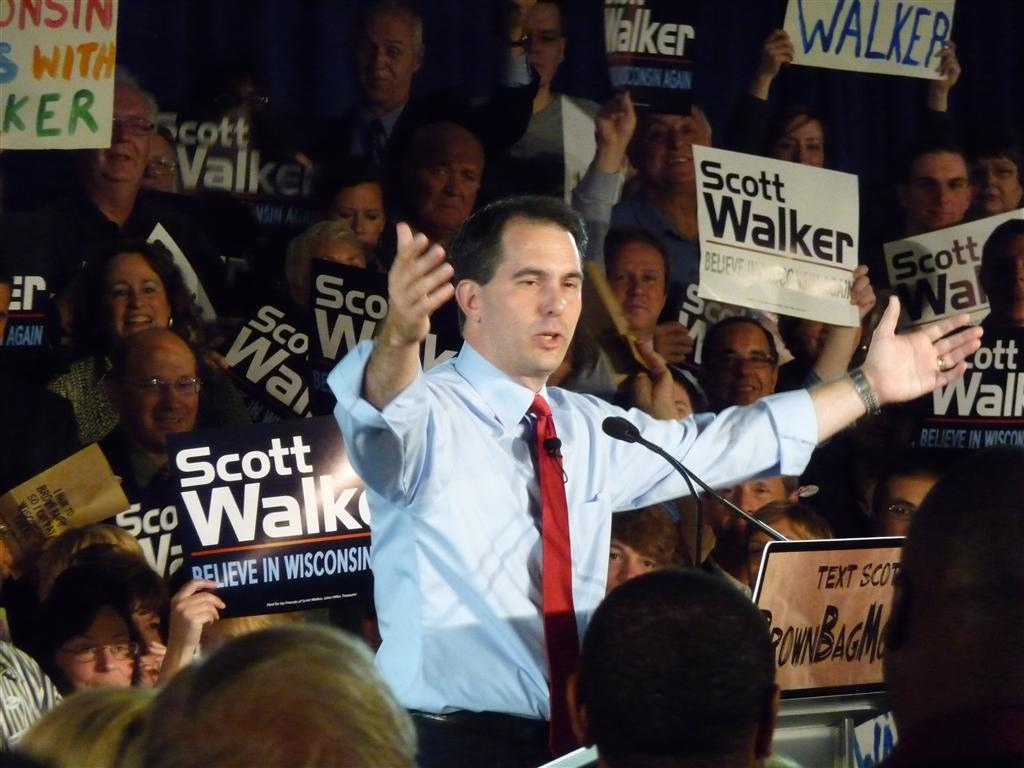

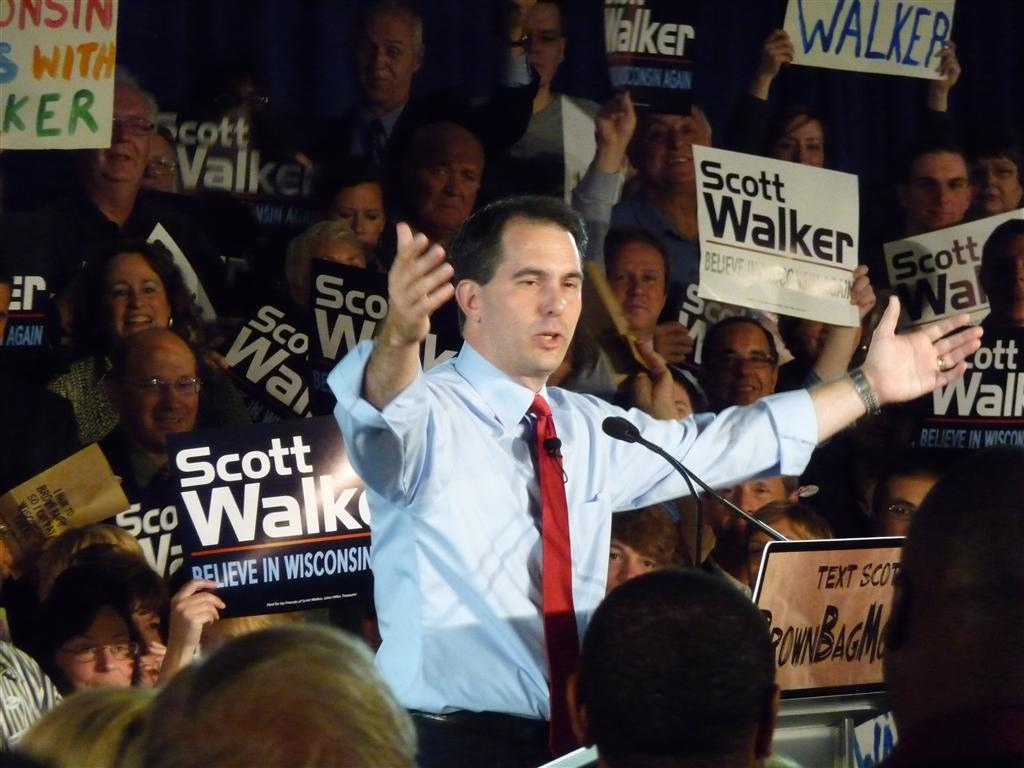

There has been a hullabaloo lately about Wisconsin Governor Walker’s lack of a degree. Some think this is a big deal, while others think almost nobody cares. In the end, we all should care about the formal education of any of our leaders. In government, business and elsewhere.

In Forbes magazine, 1998, famed management guru Peter Drucker wrote, “Get the assumptions wrong and everything that follows from them is wrong.” This is really important, because most leaders make most of their decisions based on assumptions. And many of those assumptions are based on how much, and how broad, that leader’s education.

We all make decisions on beliefs. It is easy to have incorrect beliefs. Early doctors believed that infections were due to bad blood, so they used bleeding as a cure-all for many wounds and illnesses. Untold millions of people died from this practice. A bad assumption, based on belief rather than formal study (in this case of the circulatory system) proved fatal.

In business, for thousands of years most sailors had no education about the curvature of the earth and its rotation the sun, thus they believed the world was flat and refused to sail further out to sea than the ability to keep their eyes on a shoreline. This limited trade, and delayed expansion into new markets.

Or, more recently, Steve Ballmer assumed that anyone using a smartphone would want a keyboard – because Blackberry dominated the market and had a keyboard. Thus he laughed at the iPhone launch. Oops. His assumption, and belief about the user experience, caused Microsoft to delay its entry into mobile markets and smartphones several years. Even though he had not studied smartphone user needs. Now Apple has half the smartphone market, while Blackberry and Microsoft each have less than 5%.

There are countless examples of bad decisions made when people use the wrong assumptions. At this time in Oklahoma, Texas and Colorado politicians are voting to refuse upgrading history education because the new curriculum is unacceptable to them. Their assumptions about America’s history are so strong that any factual evidence which might change those assumptions is so threatening that these politicians would prefer students be taught a fictitious history.

Our assumptions are built early in life. All through childhood our parents, aunts, uncles, religious leaders, mentors and teachers fill us with information. We process this information and build layers of assumptions. These assumptions help us to make decisions by allowing us to react based upon what we believe, rather than having to scurry around and do a research project every time a decision is required. Thus, the older we become the deeper these assumptions lie – and the more we rely on them as we undertake less and less education. As we age we decide based upon our beliefs, and less based upon any observable facts. Actually, we’ll often choose to ignore facts which indicate our assumptions and beliefs might be wrong (we call this a bias in others, and common sense when we do it ourselves.)

The more education you have, the more you can build assumptions that are likely to align with reality. It is no accident that the U.S. military uses education as a basis for promotions – rather than battlefield heroics. To move up requires officers go to war college and learn about history, politics, leadership and battles going back to long before the birth of Jesus. Good knowledge helps officers to be smarter about how to prepare for battle, organize for battle, conduct warfare, lead troops, treat a vanquished enemy and talk to the politicians for whom they work. Just look at the degrees amongst our military’s Colonels and General Officers and you find a plethora of masters and doctorate degrees. Education has long proven to be a superior warfare skill – especially when the enemy is operating on belief, guts and fight.

There are many accomplished people lacking degrees. But we should note they were successful very narrowly, and frequently in business. Steve Jobs, Bill Gates and Mark Zuckerberg are clearly high IQ people. But their success was based on founding a business at a time of technological revolution, and then building that business with zealousness. And the luck of being in the right place at the right time with a new piece of technology. They were/are not asked to be widely acclaimed in a broad spectrum of capabilities such as diplomacy, historical accuracy, legal limitations, cultural differences, the arts, scientific advances in multiple fields, warfare tactics, etc. They were not asked to develop a turnaround plan for a bankrupt auto manufacturer at the height of the Great Recession. For all their great wealth creation, they would not be what were once called “Renaissance men.”

When Governor Walker attacks the educated, and labels them as “elites,” it should be noted that their backgrounds often mean they have more points of view to evaluate, and are more considered about the various risks which are being created by taking any specific action. Many Harvard or Columbia MBAs could never be entrepreneurs because they see the many reasons a business would likely fail, and thus they are reticent to commit. Yet, that same wider knowledge allows them to be more thoughtful when evaluating the options and making decisions regarding opening new plants, negotiating with unions, expanding distribution and financing options.

Further, while it is true that you can be smart and not have a degree, the number of those who have degrees yet lack intelligence is a much, much smaller number. If one is to err in picking those you want to have advise you, or represent you, the degree(s) is not a bad first step toward identifying who is likely to provide the best insight and offer the most help.

Further, there is nothing about a degree which limits one’s ability to fight. Look at Senator Cruz from Texas. Senator Cruz’s politics seem to be somewhat aligned with Governor Walker’s, and he is widely acknowledged as a serious fighter, yet he boasts an undergraduate degree from Princeton as well as graduating from Harvard Law School. An educational background anyone would label as “elitist” and remarkably similar to President Obama’s – whose background Governor Walker has thoroughly maligned.

We expect our leaders to be widely read, and keenly aware of the complexities of life. We want our attorney’s to have law degrees and pass the bar exam. We want our physicians to have medical degrees and pass the Boards. Increasingly we want our business leaders to have MBAs. We understand that education informs our minds, and helps us develop assumptions for making good decisions. We should not belittle this, nor be accepting of someone who implies that lacking a formal education is meaningless.

by Adam Hartung | Feb 12, 2015 | Current Affairs, Disruptions, Innovation, Leadership, Web/Tech

Despite huge fanfare at launch, after a few brief months Google Glass is no longer on the market. The Amazon Fire Phone was also launched to great hype, yet sales flopped and the company recently took a $170M write off on inventory.

Fortune mercilessly blamed Fire Phone’s failure on CEO Jeff Bezos. The magazine blamed him for micromanaging the design while overspending on development, manufacturing and marketing. To Fortune the product was fatally flawed, and had no chance of success according to the article.

Similarly, the New York Times blasted Google co-founder and company leader Sergie Brin for the failure of Glass. He was held responsible for over-exposing the product at launch while not listening to his own design team.

Both these articles make the common mistake of blaming failed new products on (1) the product itself, and (2) some high level leader that was a complete dunce. In these stories, like many others of failed products, a leader that had demonstrated keen insight, and was credited with brilliant work and decision-making, simply “went stupid” and blew it. Really?

Unfortunately there are a lot of new products that fail. Such simplistic explanations do not help business leaders avoid a future product flop. But there are common lessons to these stories from which innovators, and marketers, can learn in order to do better in the future. Especially when the new products are marketplace disrupters; or as they are often called, “game changers.”

Do you remember Segway? The two wheeled transportation device came on the market with incredible fanfare in 2002. It was heralded as a game changer in how we all would mobilize. Founders predicted sales would explode to 10,000 units per week, and the company would reach $1B in sales faster than ever in history. But that didn’t happen. Instead the company sold less than 10,000 units in its first 2 years, and less than 24,000 units in its first 4 years. What was initially a “really, really cool product” ended up a dud.

There were a lot of companies that experimented with Segways. The U.S. Postal Service tested Segways for letter carriers. Police tested using them in Chicago, Philadelphia and D.C., gas companies tested them for Pennsylvania meter readers, and Chicago’s fire department tested them for paramedics in congested city center. But none of these led to major sales. Segway became relegated to niche (like urban sightseeing) and absurd (like Segway polo) uses.

Segway tried to be a general purpose product. But no disruptive product ever succeeds with that sort of marketing. As famed innovation guru Clayton Christensen tells everyone, when you launch a new product you have to find a set of unmet needs, and position the new product to fulfill that unmet need better than anything else. You must have a very clear focus on the product’s initial use, and work extremely hard to make sure the product does the necessary job brilliantly to fulfill the unmet need.

Nobody inherently needed a Segway. Everyone was getting around by foot, bicycle, motorcycle and car just fine. Segway failed because it did not focus on any one application, and develop that market as it enhanced and improved the product. Selling 100 Segways to 20 different uses was an inherently bad decision. What Segway needed to do was sell 100 units to a single, or at most 2, applications.

Segway leadership should have studied the needs deeply, and focused all aspects of the product, distribution, promotion, training, communications and pricing for that single (or 2) markets. By winning over users in the initial market Segway could have made those initial users very loyal, outspoken customers who would recommend the product again and again – even at a $4,000 price.

Segway should have pioneered an initial application market that could grow. Only after that could Segway turn to a second market. The first market could have been using Segway as a golfer’s cart, or as a walking assist for the elderly/infirm, or as a transport device for meter readers. If Segway had really focused on one initial market, developed for those needs, and won that market it would have started a step-wise program toward more applications and success. By thinking the general market would figure out how to use its product, and someone else would develop applications for specific market needs, Segway’s leaders missed the opportunity to truly disrupt one market and start the path toward wider success.

The Fire Phone had a great opportunity to grow which it missed. The Fire Phone had several features making it great for on-line shopping. But the launch team did not focus, focus, focus on this application. They did not keep developing apps, databases and ways of using the product for retailing so that avid shoppers found the Fire Phone superior for their needs. Instead the Fire Phone was launched as a mass-market device. Its retail attributes were largely lost in comparisons with other general purpose smartphones.

The Fire Phone had a great opportunity to grow which it missed. The Fire Phone had several features making it great for on-line shopping. But the launch team did not focus, focus, focus on this application. They did not keep developing apps, databases and ways of using the product for retailing so that avid shoppers found the Fire Phone superior for their needs. Instead the Fire Phone was launched as a mass-market device. Its retail attributes were largely lost in comparisons with other general purpose smartphones.

People already had Apple iPhones, Samsung Galaxy phones and Google Nexus phones. Simultaneously, Microsoft was pushing for new customers to use Nokia and HTC Windows phones. There were plenty of smartphones on the market. Another smartphone wasn’t needed – unless it fulfilled the unmet needs of some select market so well that those specific users would say “if you do …. and you need…. then you MUST have a FirePhone.” By not focusing like a laser on some specific application – some specific set of unmet needs – the “cool” features of the Fire Phone simply weren’t very valuable and the product was easy for people to pass by. Which almost everyone did, waiting for the iPhone 6 launch.

This was the same problem launching Google Glass. Glass really caught the imagination of many tech reviewers. Everyone I knew who put on Glass said it was really cool. But there wasn’t any one thing Glass did so well that large numbers of folks said “I have to have Glass.” There wasn’t any need that Glass fulfilled so well that a segment bought Glass, used it and became religious about wearing Glass all the time. And Google didn’t improve the product in specific ways for a single market application so that users from that market would be attracted to buy Glass. In the end, by trying to be a “cool tool” for everyone Glass ended up being something nobody really needed. Exactly like Segway.

Microsoft recently launched its Hololens. Again, a pretty cool gadget. But, exactly what is the target market for Hololens? If Microsoft proceeds down the road of “a cool tool that will redefine computing,” Hololens will likely end up with the same fate as Glass, Segway and Fire Phone. Hololens marketing and development teams have to find the ONE application (maybe 2) that will drive initial sales, cater to that application with enhancements and improvements to meet those specific needs, and create an initial loyal user base. Only after that can Hololens build future applications and markets to grow sales (perhaps explosively) and push Microsoft into a market leading position.

Microsoft recently launched its Hololens. Again, a pretty cool gadget. But, exactly what is the target market for Hololens? If Microsoft proceeds down the road of “a cool tool that will redefine computing,” Hololens will likely end up with the same fate as Glass, Segway and Fire Phone. Hololens marketing and development teams have to find the ONE application (maybe 2) that will drive initial sales, cater to that application with enhancements and improvements to meet those specific needs, and create an initial loyal user base. Only after that can Hololens build future applications and markets to grow sales (perhaps explosively) and push Microsoft into a market leading position.

All companies have opportunities to innovate and disrupt their markets. Most fail at this. Most innovations are thrown at customers hoping they will buy, and then simply dropped when sales don’t meet expectations. Most leaders forget that customers already have a way of getting their jobs done, so they aren’t running around asking for a new innovation. For an innovation to succeed launchers must identify the unmet needs of an application, and then dedicate their innovation to meeting those unmet needs. By building a base of customers (one at a time) upon which to grow the innovation’s sales you can position both the new product and the company as market leaders.

When Mr. Immelt took the job of CEO GE sold for about $40/share. Last week it was trading for about $25/share. A decline of 37.5%. During that same time period the Dow Jones Industrial Average, of which GE is the oldest component, rose from 9,600 to 17,900. An increase of 86.5%. This has been a very, very long period of quite unsatisfactory performance for Mr. Immelt.

When Mr. Immelt took the job of CEO GE sold for about $40/share. Last week it was trading for about $25/share. A decline of 37.5%. During that same time period the Dow Jones Industrial Average, of which GE is the oldest component, rose from 9,600 to 17,900. An increase of 86.5%. This has been a very, very long period of quite unsatisfactory performance for Mr. Immelt.