by Adam Hartung | Jun 30, 2015 | Current Affairs, In the Swamp, In the Whirlpool, Leadership

24×7 Wall Street just released its fourth annual analysis of the worst companies to work for in America. By looking across all four reports it is possible to identify likely problems which will be valuable for investors, employees (current and prospective,) suppliers and communities to know.

Trend 1- Low minimum wages & “Wage gap” issues remain a big deal

Trend 1- Low minimum wages & “Wage gap” issues remain a big deal

The lists are dominated by retailers. Of the 30 unique companies identified, exactly half (15) were retailers. A handful were on the list 2 or more years. Consistently these employees complained about low wages.

By paying minimum wage, and often refusing to hire employees full time, the companies keep costs of brick and mortar store operations lower.

However, this takes a toll on employee morale as overall pay does not meet minimum living standards. Further employees feel heavily overworked and stressed, while having no job security. Often this leads to employee unhappiness with senior management, frequently offering low evaluations of the CEO – who makes 1,000 times their annual earnings.

As employees fight for higher wages, and a reduction in the “wage gap,” it will apply pressure to the sustainability of these retailers who rely on very low pay to maintain (or enhance) profits. The trend to a higher minimum wage will challenge profit growth – or maintenance – in these companies.

Trend 2 – Employees often “see change coming” and become negatively vocal

Jos. A Banks jumped onto the list as #4 in 2013. Just before a major shake-up and being acquired by Men’s Wearhouse. Family Dollar also appeared on the list in 2014 (#9,) only to be embroiled in a takeover battle with Dollar General, and finally aquired by Dollar Tree within 7 months. Office Max appeared on the list (#5) in 2012, and was acquired by Office Depot 8 months later. And, of course, Radio Shack made the list in 2012 (#3,) 2013 (#5) and 2014 (#11) only to file bankruptcy in 2015.

Employees can see when something bad is impending, likely jeopardizing their livelihoods, and start talking about it.

Similarly, growing internet threats are often picked-up by employees. hh Gregg employees started complaining loudly in 2014 (#8) as their 100% commission compensation became threatened by a growing Amazon.com. And that same year Books-A-Million was #1 on the list, as part time staffers saw the same advancing Amazon. And in 2012 Game Stop (#10) employees could see how the advancing Netflix and Hulu threatened the “core business” and started to light up the complaint section.

Trend 3 – Ignoring employee unhappiness while focusing on earnings can portend a disaster

Sears and KMart (collectively Sears Holdings) made the list in 3 of the 4 years. The stock was $66 in June, 2011, and $55 in 6/12 when it made #6. By 6/13 it had declined to $39, and made the list at #7. Starting 6/14 the stock was reasonably flat, and missed the list. But then in 6/17 the stock fell to 27 and reappeared twice – as both Sears and KMart.

Employees have consistently expressed their dismay with CEO Ed Lampert, and 80% actively dislike his leadership. After the Radio Shack experience, there is ample reason to listen more to these employees than the CEO who keeps promising a turnaround – amidst a long string of large quarterly losses and declining sales.

But this also opens the door for looking at some stocks that have defied employee unrest. Dillard’s made the list all 4 years. In 2012 the stock rose from $54 to $66, yet appeared #2 on the list. In 2013 the stock rose to $85 as it made the list #3. 2014 the stock made it to $119, and was sixth. In 2015 the stock peaked at $149, but has recently declined to $111 as it made the list #2.

Similarly Express Scripts rose from $53 in 2012 to $62 in 2013 when it appeared on the list in position #2. In 2014 it rose to $71 as it remained #2. And it 2015 the stock is at $85 as it topped the list #1.

It would be worthwhile to look at the clues employees are sending. Express Scripts employees are loudly complaining (louder than literally any other company) across multiple years of being overworked, overstressed, underpaid and without any job security. As are Dillard’s employees, who are the most outspoken in retail. How long will profit improvements be sustainable in these companies?

While the data is less clear on Dollar General, it appeared on the list as #4 in 2013. Then Family Dollar appeared on the list as #9 in 2014. Dollar General subsequently tried buying Family Dollar, and reappeared on the list as #10 in 2015. What are employees saying about the sustainability of the “dollar store” segment in a very tough retail market with growing internet competitors?

Any CEO can slash employee costs and payroll for a few years, but at some point the model simply collapses – aka, Sears Holdings and Radio Shack. Or there is a loss of identity as suffered by Office Max, Jos. A Banks and Family Dollar. It would be worthwhile for anyone to listen carefully to the feedback of these employees before investing in company equity, investing one’s livelihood as an employee, investing one’s resources to be a supplier, or investing one’s tax base as a community official.

There are a number of “one off” issues on the list. Companies appear once primarily due to bad CEO performance (Xerox, #5 this year, HP #8 in 2012 as the revolving door on the CEO office reached a high pitch.) Or due to some change in market competition.

But it is possible to look through these issues – which could become future trends but show limited insight today – to see that an aggregated employee view of leadership offers insights not always found in the P&L or management’s discussion of earnings. If you choose to put your resources into these companies, be aware of the risks warnings being sent by employees!

Please refer to the 24x7WallStreet.com site for deeper information on how the list was compiled, who is on each list, and their editor’s opinions of employee comments. 24×7 list in 2015 – 24×7 list in 2014 – 24×7 list in 2013 – 24×7 list in 2012

by Adam Hartung | Jun 22, 2015 | Current Affairs, Defend & Extend, Lock-in

The Economic Policy Institute issued its most recent report on CEO pay yesterday, and the title makes the point clearly “Top CEOs Make 300 Times More than Typical Workers.” CEOs of the 350 largest US public companies now average $16,300,000 in compensation, while typical workers average about $53,000.

Actually, it is kind of remarkable that this stat keeps grabbing attention. The 300 multiple has been around since 1998. The gap actually peaked in 2000 at almost 376. There has been whipsawing, but it has averaged right around 300 for 15 years.

The big change happened in the 1990s. In 1965 the multiple was 20, and by 1978 it had risen only to 30. The next decade, going into 1990 saw the multiple rise to 60. But then from 1990 to 2000 it jumped from 60 to well over 300 – where it has averaged since. So it was long ago that large company CEO pay made its huge gains, and it such compensation has now become the norm.

But this does rile some folks. After all, when a hired CEO makes more in a single workday (based on 5 day week) than the worker does in an entire year, justification does become a bit difficult. And when we recognize that this has happened in just one generation it is a sea change.

If average workers are angry, and some investors are angry, and politicians are increasingly speaking negatively about the topic why does CEO pay remain so high?

If average workers are angry, and some investors are angry, and politicians are increasingly speaking negatively about the topic why does CEO pay remain so high?

Reason 1 – Because they can

CEOs are like kings. They aren’t elected to their position, they are appointed. Usually after several years of grueling internecine political warfare, back-stabbing colleagues and gerrymandering the organization. Once in the position, they pretty much get to set their own pay.

Who can change the pay? Ostensibly the Board of Directors. But who makes up most Boards? CEOs (and former CEOs). It doesn’t do any Board member’s reputation any good with his peers to try and cut CEO pay. You certainly don’t want your objection to “Joe’s” pay coming up when its time to set your pay.

Honestly, if you could set your own pay what would it be? I reckon most folks would take as much as they could get.

Reason 2 – the Lake Wobegon effect

NPR (National Public Radio) broadcasts a show about a fictional, rural Minnesota town called Lake Wobegon where “the women are strong, the men are good-looking, and all of the children are above average.”

Nice joke, until you apply it to CEOs. The top 350 CEOs are accomplished individuals. Which 175 are above average, and which 175 are below average? Honestly, how does a Board judge? Who has the ability to determine if a specific CEO is above average, or below average?

So when the “average” CEO pay is announced, any CEO would be expected to go to the Board, tell them the published average and ask “well, don’t you think I’ve done a great job? Don’t you think I’m above average? If so, then shouldn’t I be compensated at some percentage greater than average?”

Repeat this process 350 times, every year, and you can see how large company CEO pay keeps going up. And data in the EPI report supports this. Those who have the greatest pay increase are the 20% who are paid the lowest. The group with the second greatest pay increase are the 20% in the next to lowest paid quintile. These lower paid CEOs say “shouldn’t I be paid at least average – if not more?”

The Board agrees to this logic, since they think the CEO is doing a good job (otherwise they would fire him.) So they step up his, or her, pay. This then pushes up the average. And every year this process is repeated, pushing pay higher and higher and higher.

Oh, and if you replace a CEO then the new person certainly is not going to take the job for below-average compensation. They are expected to do great things, so they must be brought in with compensation that is up toward the top. The recruiters will assure the Board that finding the right CEO is challenging, and they must “pay up” to obtain the “right talent.” Again, driving up the average.

Reason 3 – It’s a “King’s Court”

Today’s large corporations hire consultants to evaluate CEO performance, and design “pay for performance” compensation packages. These are then reviewed by external lawyers for their legality. And by investment bankers for their acceptability to investors. These outside parties render opinions as to the CEO’s performance, and pay package, and overall pay given.

Unfortunately, these folks are hired by the CEO and his Board to render these opinions. Meaning, the person they judge is the one who pays them. Not the employees, not a company union, not an investor group and not government regulators. They are hired and paid by the people they are judging.

Thus, this becomes something akin to an old fashioned King’s Court. Who is in the Boardroom that gains if they object to the CEO pay package? If the CEO selects the Board (and they do, because investors, employees and regulators certainly don’t) and then they collectively hire an outside expert, does anyone in the room want that expert to say the CEO is overpaid?

If they say the CEO is overpaid, how do they benefit? Can you think of even one way? However, if they do take this action – say out of conscious, morality, historical comparisons or just obstreperousness – they risk being asked to not do future evaluations. And, even worse, such an opinion by these experts places their clients (the CEO and Board) at risk of shareholder lawsuits for not fulfilling their fiduciary responsibility. That’s what one would call a “lose/lose.”

And, let’s not forget, that even if you think a CEO is overpaid by $10million or $20million, it is still a rounding error in the profitability of these 350 large companies. Financially, to the future of the organization, it really does not matter. Of all the issues a Board discusses, this one is the least important to earnings per share. When the Board is considering the risks that could keep them up at night (cybersecurity, technology failure, patent infringement, compliance failure, etc.) overpaying the CEO is not “up the list.”

The famed newsman Robert Krulwich identified executive compensation as an issue in the 1980s. He pointed out that there were no “brakes” on executive compensation. There is no outside body that could actually influence CEO pay. He predicted that it would rise dramatically. He was right.

The only apparent brake would be government regulation. But that is a tough sell. Do Americans want Congress, or government bureaucrats, determining compensation for anyone? Americans can’t even hardly agree on a whether there should be a minimum wage at all, much less where it should be set. Rancor against executive compensation may be high, but it is a firecracker compared to the atomic bomb that would be detonated should the government involve itself in setting executive pay.

Not to mention that since the Supreme Court ruling in the case of Citizens United made it possible for companies to invest heavily in elections, it would be hard to imagine how much company money large company CEOs would spend on lobbying to make sure no such regulation was ever passed.

How far can CEO pay rise? We recently learned that Jamie Dimon, CEO of JPMorganChase, has amassed a net worth of $1.1B. It increasingly looks like there may not be a limit.

by Adam Hartung | Jun 14, 2015 | Current Affairs, In the Rapids, Leadership, Web/Tech

Dick Costolo was let go from his role as CEO of Twitter, to be replaced by a former CEO that was also fired. Unfortunately, it looks very strongly as if the Board made this decision for the wrong reasons.

Even though investors have been unhappy with Twitter’s share price, as CEO Mr. Costolo was doing a decent job of growing the company and improving profits. And even though analysts keep offering reasons why he was fired, it looks mostly as if this was a political decision in a company with a “soap opera” executive culture. Investors should be worried.

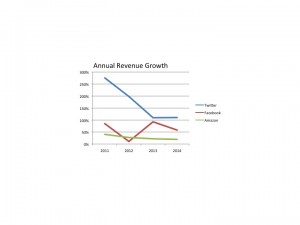

Let’s compare Mr. Costolo to CEO Zuckerberg’s performance at Facebook, and Mr. Bezos’ performance at Amazon. The latter two have been widely heralded for their leadership, so it sets a pretty good bar.

None of these three companies have enough earnings to matter. If you aren’t a growth investor, and you always value a company on earnings, then none of these are your cup of tea. All are evaluated on revenue and user metrics.

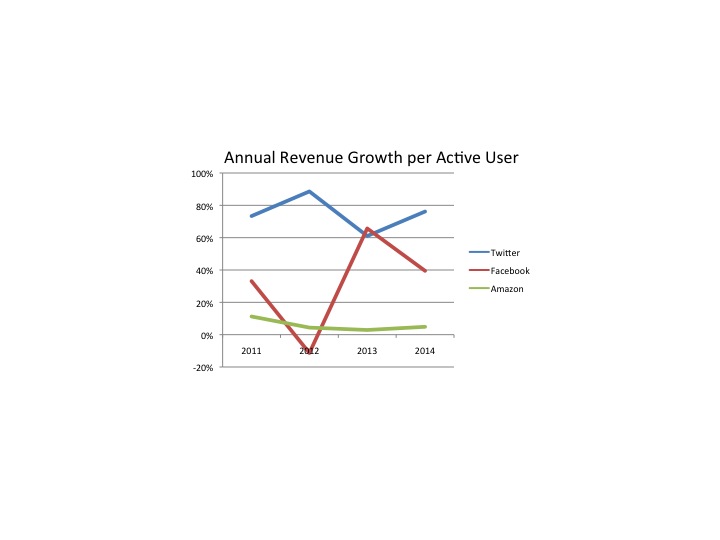

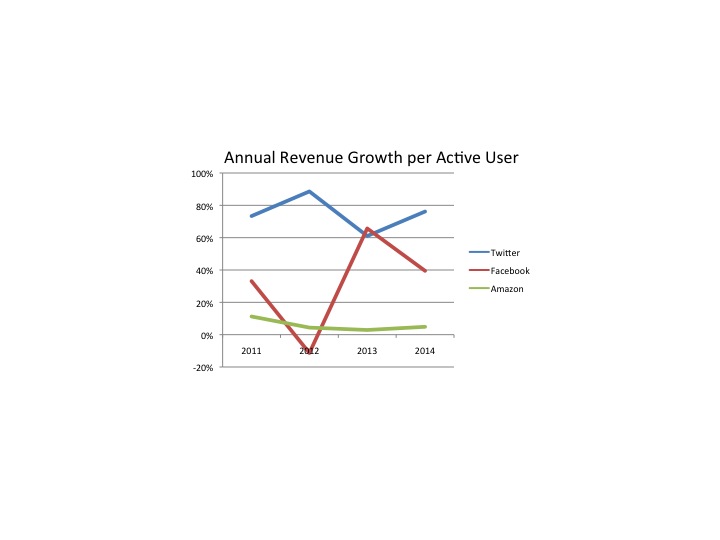

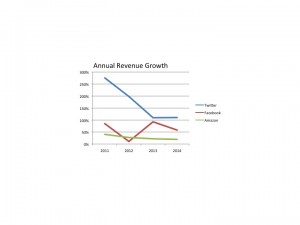

As you can see, Twitter’s revenue growth exceeds its comparators. Yes, its decline has been more dramatic, but we are comparing Twitter to companies that are much older and bigger. The net is to understand that revenues are growing, and at a better clip than Facebook and Amazon.

As you can see, Twitter’s revenue growth exceeds its comparators. Yes, its decline has been more dramatic, but we are comparing Twitter to companies that are much older and bigger. The net is to understand that revenues are growing, and at a better clip than Facebook and Amazon.

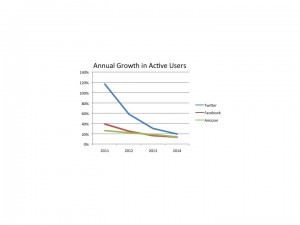

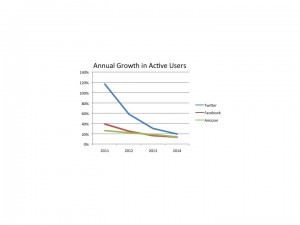

Next we should look at active monthly users. Again, these numbers are growing at all 3. And some analysts have said it is the deceleration in the rate of new user growth that doomed Mr. Costolo. But this defies logic given that during his tenure Twitter has dramatically outperformed its competition.

Next we should look at active monthly users. Again, these numbers are growing at all 3. And some analysts have said it is the deceleration in the rate of new user growth that doomed Mr. Costolo. But this defies logic given that during his tenure Twitter has dramatically outperformed its competition.

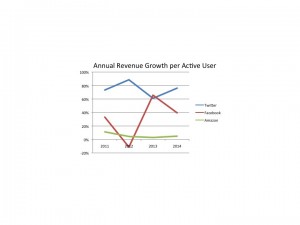

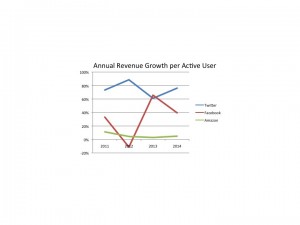

Lastly, let’s look at the “quality” of users. We can measure this by calculating the revenue per user. If this goes up, then the company is growing it top line by gaining more revenue per user – it is not “discounting” its way to higher volume. Instead,we can expect profits to improve based upon growth in this metric.

And here we can see that Twitter has wildly outperformed Facebook and Amazon. Twitter has grown its revenue per user by over 9-fold in the last 4 years, an excellent 75% per year compounded. Facebook, by comparison, roughly tripled its revenue/user (still very good) creating a 25%/year growth (certainly not to be sneezed at.) Amazon’s growth per user across the full 4 years was 25% – or about 4%/year.

And here we can see that Twitter has wildly outperformed Facebook and Amazon. Twitter has grown its revenue per user by over 9-fold in the last 4 years, an excellent 75% per year compounded. Facebook, by comparison, roughly tripled its revenue/user (still very good) creating a 25%/year growth (certainly not to be sneezed at.) Amazon’s growth per user across the full 4 years was 25% – or about 4%/year.

It isn’t hard to see that Mr. Costolo has been doing a pretty good job leading Twitter.

But Twitter has had a very checkered past when it comes to leaders. Several articles have been written about the revolving door on the CEO office, with founders back-stabbing each other as money is raised and efforts are made to improve company performance technologically and financially.

The Board has shown a proclivity to spend too much time listening to rumors, and previous CEOs. Rather than focusing on exactly how many users are coming aboard, and how much revenue is generated on those users.

The returning CEO was himself previously replaced. And during his tenure there were many technical problems. Why he would be inserted, and the best performing CEO in company history shunted aside is completely unclear. But for investors, employees, users (of which I am one) and customers this change in leadership looks to be poorly conceived, and quite concerning. Mr. Costolo was doing a pretty good job.

Data on revenues came from Marketwatch for Twitter, Facebook and Amazon. Data on users (in Amazon’s case customers) came from Statista.com for Twitter, Facebook and Amazon. Charts were created by Adam Hartung (C).

by Adam Hartung | Jun 7, 2015 | Defend & Extend, In the Swamp, Innovation, Leadership, Transparency

Did you ever notice that Human Resource (HR) practices are designed to lock-in the past rather than grow? A quick tour of what HR does and you quickly see they like to lock-in processes and procedures, insuring consistency but offering no hope of doing something new. And when it comes to hiring, HR is all about finding people that are like existing employees – same school, same degrees, same industry, same background. And HR tries its very hardest to insure conformity amongst employees to historical standard – especially regarding culture.

Several years ago I was leading an innovation workshop for leaders in a company that made nail guns, screw guns, nails and screws. Once a market leader, sales were struggling and profits were nearly nonexistent due to the emergence of competitors from Asia. Some of their biggest distributors were threatening to drop this company’s line altogether unless there were more concessions – which would insure losses.

They liked to call themselves a “fastener company,” which has long been the trend with companies that like to make it sound as if they do more than they actually do.

I asked the simple question “where is the growth in fasteners?” The leaders jumped right in with sales numbers on all their major lines. They were sure that growth was in auto-loading screwguns, and they were hard at work extending this product line. To a person, these folks were sure they new where growth existed.

But I had prepared prior to the meeting. There actually was much higher growth in adhesives. Chemical attachment was more than twice the growth rate of anything in the old nail and screw business. Even loop-and-hook fasteners [popularly referred to by the tradename Velcro(c)] was seeing much greater growth than the old-line mechanical products.

They looked at me blank-faced. “What does that have to do with us?” the head of sales finally asked. The CEO and everyone else nodded in agreement.

I pointed out to them they said they were in the fastener business. Not the nail and screw business. The nail and screw business had become a bloody fight, and it was not going to get any better. Why not move into faster growing, less competitive products?

Competitors were making lots of battery powered and air powered tools beyond nail guns and screw guns, and their much deeper product lines gave them much higher favorability with retail merchandisers and professional tool distributors. Plus, competitor R&D into batteries was already showing they could produce more powerful and longer-lasting tools than my client. In a few major retailers competitors already had earned the position of “category leader” recommending the shelf space and layout for ALL competitors, giving them a distinct advantage.

This company had become myopic, and did not even realize it. The people were so much alike that they could finish each others sentences. They liked working together, and had built a tightly knit culture. The HR head was very proud of his ability to keep the company so harmonious.

Only, it was about to go bankrupt. Lacking diversity in background, they were unable to see beyond their locked-in business model. And there sure wasn’t anyone who would “rock the boat” by admitting competitors were outflanking them, or bringing up “wild ideas” for new markets or products.

According to the New York Times 80% of hiring is done based on “cultural fit.” Which means we hire people we want to hang out with. Which almost always means people that are a lot like ourselves. Regardless of what we really need in our company. Thus companies end up looking, thinking and acting very homogenously.

It is common amongst management authors and keynote speakers to talk about creating “high-performance teams.” The vaunted Jim Collins in “Good to Great” uses the metaphor of a company as a bus. Every company should have a “core” and every employee should be single-mindedly driving that “core.” He says that it is the role of good leaders to get everyone on the bus to “core.” Anyone who isn’t 100% aligned – well, throw them off the bus (literally, fire them.)

We see this phenomenon in nepotism. Where a founder, CEO or Chairperson who succeeds uses their leadership position to promote relatives into high positions.

Wal-Mart’s Board of Directors, for example, recently elected the former Chairman’s son-in-law to the position of Chairman. He appears accomplished, but today Wal-Mart’s problem is Amazon and other on-line retail. Wal-Mart desperately needs outside thinking so it can move beyond its traditional brick-and-mortar business model, not someone who’s indoctrinated in the past.

The Reputation Institute just completed its survey of the most reputable retailers in the USA. Top of the list was Amazon, for the third straight year. Wal-Mart wasn’t even in the top 10, despite being the largest U.S. retailer by a considerable margin. Wal-Mart needs someone at the top much more like Jeff Bezos than someone who comes from the family.

Despite what HR often says, it is incredibly important to have high levels of diversity. It’s the only way to avoid becoming myopic, and finding yourself with “best practices” that don’t matter as competitors overwhelm your market.

Despite what HR often says, it is incredibly important to have high levels of diversity. It’s the only way to avoid becoming myopic, and finding yourself with “best practices” that don’t matter as competitors overwhelm your market.

Ever wonder why so many CEOs turn to layoffs when competitors cause sales and/or profits to stall? They are trying to preserve the business model, and everyone reporting to them is doing the same thing. Instead of looking for creative ways to grow the business – often requiring a very different business model – everyone is stuck in roles, processes and culture tied to the old model. As everyone talks to each other there is no “outsider” able to point out obvious problems and the need for change.

In 2011, while he was still CEO, I wrote a column titled “Why Steve Jobs Couldn’t Find a Job Today.” The premise was pretty simple. Steve Jobs was not obsessed with “cultural fit,” nor was he a person who shied away from conflict. He obsessed about results. But no HR person would consider a young Steve Jobs as a manager in their company. He would be considered too much trouble.

Yet, Steve Jobs was able to take a nearly dead Macintosh company and turn it into a leader in mobile products. Clearly, a person very talented in market sensing and identifying new solutions that fit trends. And a person willing to move toward the trend, rather than obsess about defending and extending the past.

Does your organization’s HR insure you would seek out, recruit and hire Steve Jobs, or Jeff Bezos? Or are you looking for good “cultural fit” and someone who knows “how to operate within that role.” Do you look for those who spot and respond to trends, or those with a history related to how your industry or business has always operated? Do you seek people who ask uncomfortable questions, and propose uncomfortable solutions – or seek people who won’t make waves?

Does your organization’s HR insure you would seek out, recruit and hire Steve Jobs, or Jeff Bezos? Or are you looking for good “cultural fit” and someone who knows “how to operate within that role.” Do you look for those who spot and respond to trends, or those with a history related to how your industry or business has always operated? Do you seek people who ask uncomfortable questions, and propose uncomfortable solutions – or seek people who won’t make waves?

Too many organizations suffer failure simply because they lack diversity. They lack diversity in geographic sales, markets, products and services – and when competition shifts sales stall and they fall into a slow death spiral.

And this all starts with insufficient diversity amongst the people. Too much “cultural fit” and not enough focus on what’s really needed to keep the organization aligned with customers in a fast-changing world. If you don’t have the right people around you, in the discussion, then you’re highly unlikely to develop the right solution for any problem. In fact, you’re highly unlikely to even ask the right question.

by Adam Hartung | May 31, 2015 | Current Affairs, Defend & Extend, In the Whirlpool, Leadership, Web/Tech

Information technology (IT) services company Computer Sciences Corporation (CSC) recently announced it is splitting into two separate companies. One will “focus” on commercial markets, the other will “focus” on government contracts. Ostensibly, as we’ve heard before, leadership would like investors, employees and customers to believe this is the answer for a company that has incurred a number of high profile failed contracts, a turnover in leadership, vast losses and declining revenue.

Oh boy.

After years of poor performance, and an investigation by the UK parliament into a failed contract for the National Health Services, in 2012 CSC brought in a new CEO. Like most new CEOs, his first action was to announce a massive cost-cutting program. That primarily meant vast layoffs. So out the door went thousands of people in order to hopefully improve the P&L.

Only a services company doesn’t have any hard assets. The CSC business requires convincing companies, or government agencies, to let them take over their data centers, or PC deployment, or help desk, or IT development, or application implementation – in other words to outsource some part (or all) of the IT work that could be done internally. Winning this work has been an effort to demonstrate you can hire better people, that are more productive, at lower cost than the potential client.

So when CSC undertook a massive layoff, service levels declined. It was unavoidable. Where before CSC had 10 people doing something (or 1,000) now they have 7 (or 700). It’s not hard to imagine what happens next. Morale declines as layoffs ensue, and the overworked remaining employees feel (and perhaps really are) overworked. People leave for better jobs with higher pay and less stress. Yet, the contract requirements remain, so clients often start complaining about performance, leading to more pressure on the remaining employees. A vicious whirlpool of destruction starts, as things just keep getting worse.

Immediately after taking the CEO job in 2012 Mike Lawrie declared a massive $4.3B loss. This allowed him to “bring forward” anticipated costs of the anticipated layoffs, cancelled contracts, etc. Most importantly, it allowed him to “cost shift” future costs into his first year in the job – the year in which he would not be fired, regardless how much he wrote off. This is a classic financial machination applied by “turnaround CEOs” in order to blame the last guy for not being truthful about how badly things were, while guaranteeing the end of the new guy’s first year would show a profit due to the huge cost shift.

True to expectations, after one year with Lawrie as CEO, CSC declared a $1B profit for fyscal 2013 (about 20% of the previous write-off.) But then fyscal 2014 returned to the previous norm, as profits shrunk to just $674M on about $12B revenues (~5% net margin.) For 4th quarter of fyscal 2015 revenues dropped another 12.6% – not hard to imagine given the layoffs and ensuing customer dissatisfaction. Most troubling, the commercial part of CSC, which represents 75% of revenue, saw all parts of the business decline between 15-20%, while the federal contracting (much harder to cancel) remained flat. This is not the trajectory of a turnaround.

CEO Lawrie blames the deteriorating performance on execution missteps. And he has promised to keep his eyes carefully on the numbers. Although he has admitted that he doesn’t really know when, or if, CSC will return to any sort of growth.

No wonder that for more than a year prior to this split CSC was unable to sell itself. Despite a lot of hard effort, no banker was able to put together a deal for CSC to be purchased by a competitor or a private banking (hedge fund) operation.

If none of the professionals in making splits and turnarounds were willing to take on this deal, why should individual investors? In this case, watching people walk away should be a clear indicator of how bad things are, and how clueless leadership is regarding a fix for the problems.

The real problem at CSC isn’t “execution.” The real problem is that the market has shifted substantially. For decades CSC’s outsourcing business was the norm. But today companies don’t need a lot of what CSC outsources. They are closing down those costly operations and replacing them with cloud services, cloud application development and implementation, mobile deployments and significant big data analytics. Or looking for new services to solve problems like cybersecurity threats. CSC quite simply hasn’t done anything in those markets, and it is far, far behind. It is a big dinosaur rapidly being overtaken by competitors moving more quickly to new solutions.

One of CSC’s biggest competitors is IBM, which itself has had a series of woes. However, IBM has very publicly set up a partnership with Apple and is moving rapidly to develop industry-specific software as a service (SaaS) offerings that are mobile and operate in the cloud. These targeted enterprise solutions in health care, finance and other industries are designed to make the services offered by CSC obsolete.

Although it may have had a huge client base of 1,000 customers. And CSC brags that 175 of the Fortune 500 buy some services from it, exactly what does CSC bring to the table to keep these customers? Years of cost cutting means the company has not invested in the kinds of solutions being offered by IBM and competitors such as Accenture, HP and Dell domestically – and WiPro, TCS (Tata Consulting Services,) Infosys and Cognizant offshore. Not to mention dozens of up-and-coming small competiters who are right on the market for targeted solutions with the latest technology such as 6D Gobal Technologies. CSC is still stuck in its 1980s consulting model, and skill set, in a world that is vastly different today.

CSC has no idea how to “focus” on clients. That would mean investing in modern solutions to rapidly changing client needs. CSC failed to do that 15 years ago when most outsourcing involved heavy use of offshore resources. And CSC has never caught up. Leadership overly relied on selling old services, and discounting. It’s model caused it to underbid projects, until the UK government almost shut the company down for its inability to deliver, and constantly hiding actual results.

CSC has no idea how to “focus” on clients. That would mean investing in modern solutions to rapidly changing client needs. CSC failed to do that 15 years ago when most outsourcing involved heavy use of offshore resources. And CSC has never caught up. Leadership overly relied on selling old services, and discounting. It’s model caused it to underbid projects, until the UK government almost shut the company down for its inability to deliver, and constantly hiding actual results.

Now CSC lacks any of the capabilities, people or skills to offer clients what they want. Its diffuse customer base is more a liability than a benefit, because these customers are “end of life” for the services CSC offers. Years of declining revenues demonstrate that as value declines, contracts are either allowed to go to very cheap offshore providers, lapse completely or cancelled early in order to shift client resources to more important projects where CSC cannot compete.

This split is just an admission that leadership has no idea what to do next. Customers are leaving, and revenues are declining. Margins, at 5%, are terrible and there is no money to invest in anything new. Some of the world’s best investors have looked at CSC deeply and chosen to walk away. For employees and individual investors it is time to admit that CSC has a limited future, and it is time to find far greener pastures.

by Adam Hartung | May 22, 2015 | In the Whirlpool, Leadership, Lock-in, Web/Tech

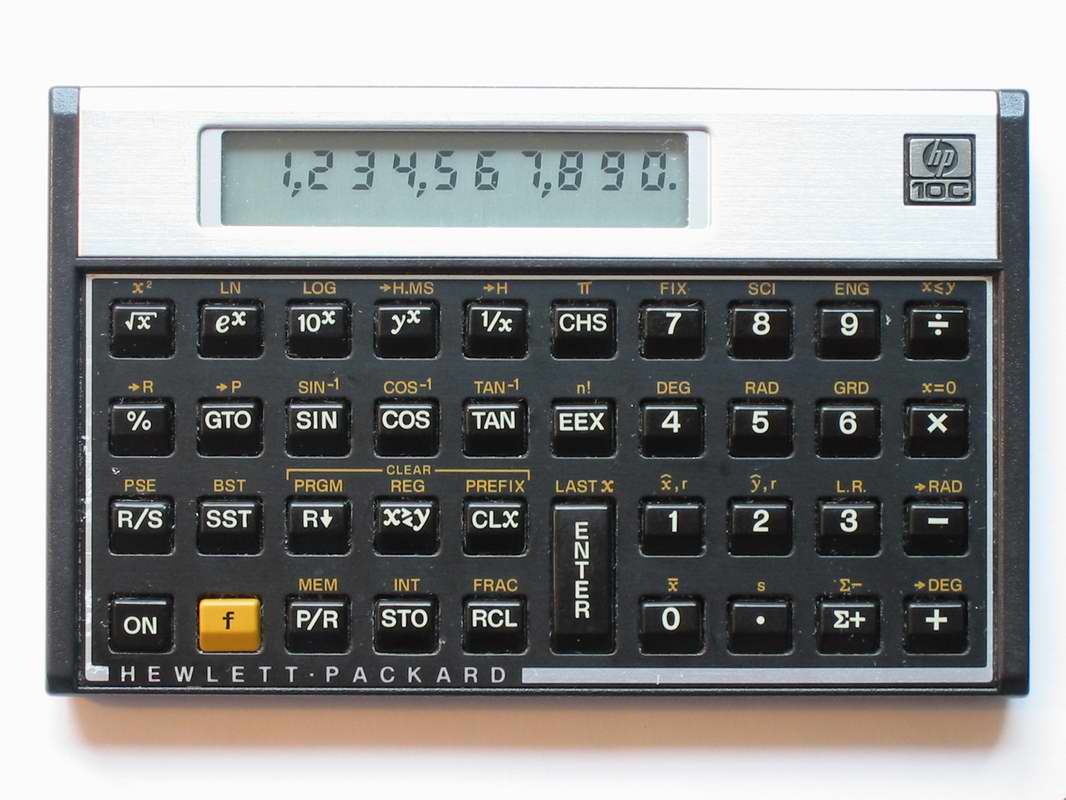

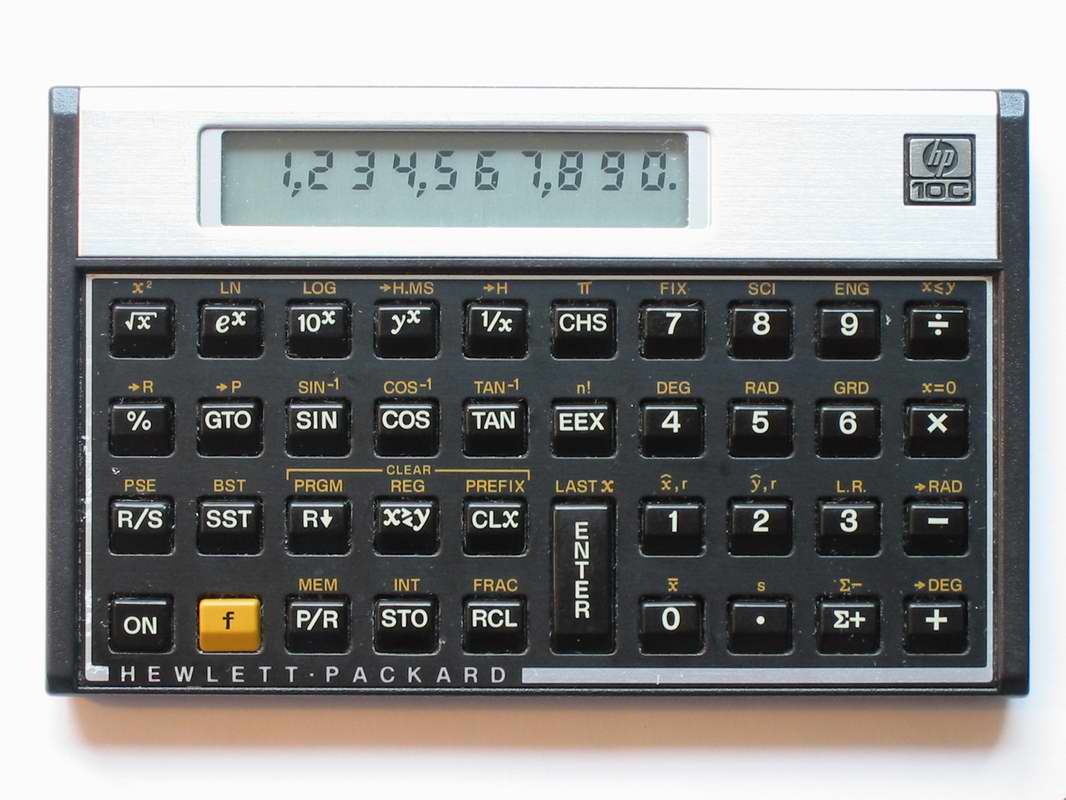

Hewlett Packard yesterday announced second quarter results. And they were undoubtedly terrible. Revenue compared to a year ago is down 7%, net income is down 21% as the growth stall at HP continues.

Yet, CEO Meg Whitman remains upbeat. She is pleased with “the continued success of our turnaround.” Which is good, because nobody else is. Rather than making new products and offering new solutions, HP has become a company that does little more than constantly restructure!

This latest effort, led by CEO Whitman, has been a split of the company into two corporations. For “strategic” (red flag) reasons, HP is dividing into a software company and a hardware company so that each can “focus” (second red flag) on its “core market” (third red flag.) But there seems to be absolutely no benefit to this other than creating confusion.

This latest restructuring is incredibly expensive. $1.8billion in restructuring charges, $1billion in incremental taxes, $400million annually in duplicated overhead services, then another $3billion in separation charges across the two new companies. That’s over $5B – which is more than HP’s net income in 2014 and 2013. There is no way this is a win for investors.

Additionally, HP has eliminated 48,000 jobs this this latest restructuring began in 2012. And the total will reach 55,000. So this is clearly not a win for employees.

The old HP will now be a hardware company, focused on PCs and printers. Both of which are declining markets as the world goes mobile. This is like the newspaper part of a media company during a split. An old business in serious decline with no clear path to sustainable sales and profits – much less growth. And in HP’s case it will be in a dog-eat-dog competitive battle to try and keep customers against Dell, Acer and Lenovo. Prices will keep dropping, and profits eroding as the world goes mobile. But despite spending $1.2billion to buy Palm (written off,) without any R&D, hard to see how this company returns profits to shareholders, generates new jobs, or launches new products for distributors and customers.

The new HP will be a software company. But it comes to market with almost no share against monster market leader Amazon, and competitors Microsoft and Cisco who are fighting to remain relevant. Even though HP spent $10B to buy ERP company Autonomy (written off) everyone has newer products, more innovation, more customers and more resources than HP.

Together there was faint hope for HP. The company could offer complete solutions. It could work with its distributors and value added resellers to develop unique vertical market solutions. By tweaking the various parts, hardware and software, HP had the possibility of building solutions that could justify premium prices and possibly create growth. But separated, these are now 2 “focused” companies that lack any new innovations, sell commodity products and lack enough share to matter in markets where share leads to winning developers and enterprise customers.

This may be the last stop for investors, and employees, to escape HP before things get a lot worse.

This may be the last stop for investors, and employees, to escape HP before things get a lot worse.

HP was the company that founded silicon valley. It was the tech place to work in the 1960s, 1970s and early 1980s. It was the Google, Facebook or Apple of that earlier time. When Carly Fiorina took over the dynamic and highly new product driven company in July, 1999 it was worth $45/share. She bought Compaq and flung HP into the commodity PC business, cutting new products and R&D. By the time the Board threw her out in 2005 the company was worth $35/share.

Mark Hurd took the CEO job, and he slashed and burned everything in sight. R&D was almost eliminated, as was new product development. If it could be outsourced, it was. And he whacked thousands of jobs. By killing any hope of growing the company, he improved the bottom line and got the stock back to $45.

Which is where it was 5 years ago today. But now HP is worth $35/share, once again. For investors, it’s been 25 years of up, down and sideways. The last 5 years the DJIA went up 80%; HP down 24%.

Companies cannot add value unless they develop new products, new solutions, new markets and grow. Restructuring after restructuring adds no value – as HP has demonstrated. For long-term investors, this is a painful lesson to learn. Let’s hope folks are getting the message loud and clear now.

by Adam Hartung | May 12, 2015 | Current Affairs, Leadership

NFL Commissioner Roger Goodall slammed Tom Brady and the New England Patriots today for what seemed, to many, like a pretty minor thing. Under-inflating balls to give the quarterback and receivers a small advantage would seem a far cry from the kind of offense causing you to suspend an MVP player for 4 games, fine the team owner $1M, and take away the coach’s #1 draft pick for 2016 and #4 draft pick for 2017.

But, largely, the Commissioner had little choice. And yes, he is making an example out of this situation.

In America the NFL is the sport. Where baseball was once “America’s game” that is no longer true. Today the NFL generates almost as much revenue as major league baseball (MLB) and the NBA combined. Players make more money than S&P 500 CEOs – and they are about the only people who do!

But the NFL has a raft of culture issues. First of all, it is really violent. The litany of players with lifetime injuries from football is remarkable. It seems like few who play in the NFL are able to go on to “regular lives” due to the remarkable stress the game puts on huge bodies colliding at remarkable speeds. There is no doubt that the game has led to many debilitating concussions, and players have been committing suicide at a surprising rate.

Remember “Bountygate?” From 2009 to 2011 the New Orleans Saints ownership and coaches paid players bonuses – “bounties” – if they injured an opposing player bad enough to have him removed from the game. This kind of thing was found to be endemic, and that some coaches had long promoted paying for injuring opposing players.

That is the kind of testosterone driven behavior that the NFL’s leadership realized was going to seriously damage the game, if not push it into legal regulation. While some fans (and in football, fan is truly short for fanatic) may have thought the practice a terrific reincarnation of Roman gladiator games, culturally this kind of behavior made the game less “family friendly” and likely to end up with ever more legal problems. The coaches were suspended, and the team lost draft picks.

Unfortunately, the NFL – despite its high pay – is nothing like baseball when it was the glory sport of America. In those days players had strict behavioral rules, and they could lose money – even their jobs – for simply getting drunk in public, or caught fornicating with someone other than their wife. Arguing with umpires caused multi-game suspensions, and fans sought out players with the quiet demeanor of Joe Dimaggio.

The NFL is rife with players struggling with criminal prosecution. Between January and July of 2013, 27 players were arrested. Between 2000 and 2013 two teams had 40 players arrested, and one had 35. The three least criminalistic teams in the league had 9 to 11 players put in handcuffs. It is a far too common sight on the news – NFL players handcuffed, or explaining to cameras why they were arrested. This is a big problem for a league that would like its players to be role models, and encourage mothers to allow their children to play the game – or go to games.

The Patriots have had their own problems. In 2007 coach Patriots’ Belichick was caught stealing signals from the New York Jets coaches. “Spygate” caused Commissioner Goodall to fine the coach $500,000 – the largest fine in history to that date. Additionally the team was stripped of its 2008 first round draft and fined $250,000. It was another example, like Bountygate, of a culture accepting of the notion that owners, coaches and players should “do whatever it takes to win,” and rules (or etiquette) be darned.

Then in 2013 Patriots’ player Aaron Hernandez was arrested for murder. Eventually he was arrested on two additional murder counts, and in just the last few months he was convicted on murder charges. As the news rolled out, we learned Mr. Hernandez had a long criminal record, including bar fights and shootings, going back to 2007. It appears as if the Patriots and the NFL turned a blind eye toward a very dangerous person – in order for the team to win more games. The “win at all costs” again appeared to be culturally dominant.

Now we have “deflategate.” Coach Belichick again in the spotlight, apparently for trying more tricks to gain an advantage – even if unfair. As the investigation continued the question became “even if Tom Brady didn’t know why the balls were deflated, as someone who touched the ball on every play why didn’t he report the issue to his coaches? Why didn’t he take personal responsibility for what could well be a rule violation, and seek to find the true answer? Why didn’t he try to play by the rules, and take care of this issue?” Instead, it appeared he was more than happy to take advantage of the situation, even if it was against the rules. Again, win at all costs – including breaking the rules.

Unfortunately this is now moving into the stadium. In recent TV interviews several people have pooh-poohed the whole issue. “What’s the big deal? Really? All this fuss over something so small?” And the comment heard over and over in “man-on-the-street” interviews “if you get caught, you get penalized.” Really – not that Mr. Brady should have reported this situation and fixed it – but rather that he got caught is all that mattered. It’s OK to cheat, just don’t get caught.

The NFL has a culture issue. In some stadiums the language is so course, and the fans so rough, that minors should never attend. And, as we said in an earlier time, “unfit company for a lady.” Tied, unfortunately, to players and coaches who implement a culture of violence, cheating and doing whatever one must to win – rather than simply playing a game.

And that is where Commissioner Goodall has to take action. He leads the league. He is the “man at the top.” It is his job, as leader, to set the tone on culture. If the NFL is to be “America’s sport” it’s his job to set the cultural tone for the sport, and demonstrate good leadership for his business, the owners, the coaches and the players. If we want fans to be sportsmanlike, it has to start with the players and those who are part of the NFL.

So there is no choice but to make an example of Mr. Brady. He sensed there was a problem. But he would rather win, and be MVP, than be honest. Wow, what a role model. And Mr. Belichick, now in in controversy #2, leads us to question if anything matters to him other than winning a superbowl ring – even if it means hiring a gun-toting shooter who can’t stay out of bar fights. And the Commissioner, like many of us, has to wonder, what is going on in that Patriots’ organization that Mr. Robert Kraft owns? What cultural tone is he setting, as the man atop the team? Is his view “win at all costs” and the rules be darned?

The NFL has a culture problem. Commissioner Goodall has his hands full. He has to deal with individualistic owners, who are rich and very powerful in their local communities. He has fans that are often far more caring of their team winning than playing by the rules. And he has players that, too often, or a very short step from prison – or committing horrendous acts of violence on the field that can maim or kill another player. He has to take stiff action, when he can, if he is to make any difference at all in trying to keep this culture from going completely off the rails.

Learn more about my public speaking, Board involvement and growth consulting at www.AdamHartung.com, or connect with me on LinkedIn, Facebook and Twitter.

by Adam Hartung | May 8, 2015 | Current Affairs, Defend & Extend, Food and Drink, In the Swamp, In the Whirlpool, Leadership

McDonald’s just had another lousy quarter. All segments saw declining traffic, revenues fell 11%. Profits were off 33%. Pretty well expected, given its established growth stall.

A new CEO is in place, and he announced is turnaround plan to fix what ails the burger giant. Unfortunately, his plan has been panned by just about everyone. Unfortunately, its a “me too” plan that we’ve seen far too often – and know doesn’t work:

- Reorganize to cut costs. By reshuffling the line-up, and throwing out a bunch of bodies management formerly said were essential, but now don’t care about, they hope to save $300M/year (out of a $4.5B annual budget.)

- Sell off 3,500 stores McDonald’s owns and operate (about 10% of the total.) This will further help cut costs as the operating budgets shift to franchisees, and McDonald’s book unit sales creating short-term, one-time revenues into 2018.

- Keep mucking around with the menu. Cut some items, add some items, try a bunch of different stuff. Hope they find something that sells better.

- Try some service ideas in which nobody really shows any faith, like adding delivery and/or 24 hour breakfast in some markets and some stores.

Needless to say, none of this sounds like it will do much to address quarter after quarter of sales (and profit) declines in an enormously large company. We know people are still eating in restaurants, because competitors like 5 Guys, Meatheads, Burger King and Shake Shack are doing really, really well. But they are winning primarily because McDonald’s is losing. Even though CEO Easterbrook said “our business model is enduring,” there is ample reason to think McDonald’s slide will continue.

Needless to say, none of this sounds like it will do much to address quarter after quarter of sales (and profit) declines in an enormously large company. We know people are still eating in restaurants, because competitors like 5 Guys, Meatheads, Burger King and Shake Shack are doing really, really well. But they are winning primarily because McDonald’s is losing. Even though CEO Easterbrook said “our business model is enduring,” there is ample reason to think McDonald’s slide will continue.

Possibly a slide into oblivion. Think it can’t happen? Then what happened to Howard Johnson’s? Bob’s Big Boy? Woolworth’s? Montgomery Wards? Size, and history, are absolutely no guarantee of a company remaining viable.

In fact, the odds are wildly against McDonald’s this time. Because this isn’t their first growth stall. And the way they saved the company last time was a “fire sale” of very valuable growth assets to raise cash that was all spent to spiffy up the company for one last hurrah – which is now over. And there isn’t really anything left for McDonald’s to build upon.

Go back to 2000 and McDonald’s had a lot of options. They bought Chipotle’s Mexican Grill in 1998, Donato’s Pizza in 1999 and Boston Market in 2000. These were all growing franchises. Growing a LOT faster, and more profitably, than McDonald’s stores. They were on modern trends for what people wanted to eat, and how they wanted to be served. These new concepts offered McDonald’s fantastic growth vehicles for all that cash the burger chain was throwing off, even as its outdated yellow stores full of playgrounds with seats bolted to the floors and products for 99cents were becoming increasingly not only outdated but irrelevant.

But in a change of leadership McDonald’s decided to sell off all these concepts. Donato’s in 2003, Chipotle went public in 2006 and Boston Market was sold to a private equity firm in 2007. All of that money was used to fund investments in McDonald’s store upgrades, additional supply chain restructuring and advertising. The “strategy” at that time was to return to “strategic focus.” Something that lots of analysts, investors and old-line franchisees love.

But look what McDonald’s leaders gave up via this decision to re-focus. McDonald’s received $1.5B for Chipotle. Today Chipotle is worth $20B and is one of the most exciting fast food chains in the marketplace (based on store growth, revenue growth and profitability – as well as customer satisfaction scores.) The value of all of the growth gains that occurred in these 3 chains has gone to other people. Not the investors, employees, suppliers or franchisees of McDonald’s.

We have to recognize that in the mid-2000s McDonald’s had the option of doing 180degrees opposite what it did. It could have put its resources into the newer, more exciting concepts and continued to fidget with McDonald’s to defend and extend its life even as trends went the other direction. This would have allowed investors to reap the gains of new store growth, and McDonald’s franchisees would have had the option to slowly convert McDonald’s stores into Donato’s, Chipotle’s or Boston Market. Employees would have been able to work on growing the new brands, creating more revenue, more jobs, more promotions and higher pay. And suppliers would have been able to continue growing their McDonald’s corporate business via new chains. Customers would have the benefit of both McDonald’s and a well run transition to new concepts in their markets. This would have been a win/win/win/win/win solution for everyone.

But it was the lure of “focus” and “core” markets that led McDonald’s leadership to make what will likely be seen historically as the decision which sent it on the track of self-destruction. When leaders focus on their core markets, and pull out all the stops to try defending and extending a business in a growth stall, they take their eyes off market trends. Rather than accepting what people want, and changing in all ways to meet customer needs, leaders keep fiddling with this and that, and hoping that cost cutting and a raft of operational activities will save the business as they keep focusing ever more intently on that old core business. But, problems keep mounting because customers, quite simply, are going elsewhere. To competitors who are implementing on trends.

The current CEO likes to describe himself as an “internal activist” who will challenge the status quo. But he then proves this is untrue when he describes the future of McDonald’s as a “modern, progressive burger company.” Sorry dude, that ship sailed years ago when competitors built the market for higher-end burgers, served fast in trendier locations. Just like McDonald’s 5-years too late effort to catch Starbucks with McCafe which was too little and poorly done – you can’t catch those better quality burger guys now. They are well on their way, and you’re still in port asking for directions.

McDonald’s is big, but when a big ship starts taking on water it’s no less likely to sink than a small ship (i.e. Titanic.) And when a big ship is badly steered by its captain it flounders, and sinks (i.e. Costa Concordia.) Those who would like to think that McDonald’s size is a benefit should recognize that it is this very size which now keeps McDonald’s from doing anything effective to really change the company. Its efforts (detailed above) are hemmed in by all those stores, franchisees, commitment to old processes, ingrained products hard to change due to installed equipment base, and billions spent on brand advertising that has remained a constant even as McDonald’s lost relevancy. It is now sooooooooo hard to make even small changes that the idea of doing more radical things that analysts are requesting simply becomes impossible for existing management.

And these leaders, frankly, aren’t even going to try. They are deeply wedded, committed, to trying to succeed by making McDonald’s more McDonald’s. They are of the company and its history. Not the CEO, or anyone on his team, reached their position by introducing a revolutionary new product, much less a new concept – or for that matter anything new. They are people who “execute” and work to slowly improve what already exists. That’s why they are giving even more decision-making control to franchisees via selling company stores in order to raise cash and cut costs – rather than using those stores to introduce radical change.

These are not “outside thinkers” that will consider the kinds of radical changes Louis V. Gerstner, a total outsider, implemented at IBM – changing the company from a failing mainframe supplier into an IT services and software company. Yet that is the only thing that will turn around McDonald’s. The Board blew it once before when it sold Chipotle, et.al. and put in place a core-focused CEO. Now McDonald’s has fewer resources, a lot fewer options, and the gap between what it offers and what the marketplace wants is a lot larger.

by Adam Hartung | Apr 30, 2015 | Current Affairs, Defend & Extend, In the Rapids, Innovation, Leadership, Web/Tech

Last week saw another slew of quarterly earnings releases. For long term investors, who hold stocks for years rather than months, these provide the opportunity to look at trends, then compare and contrast companies to determine what should be in their portfolio. It is worthwhile to compare the trends supporting the valuations of market leaders Google and Facebook.

Google once again reported higher sales and profits. And that is a good thing. But, once again, the price of Google’s primary product declined. Revenues increased because volume gains exceeded the price decline, which indicates that the market for internet ads keeps growing. But this makes 15 straight quarters of price declines for Google. Due to this long series of small declines, the average price of Google’s ads (cost per click) has declined 70%* since Q3 2011!

Google once again reported higher sales and profits. And that is a good thing. But, once again, the price of Google’s primary product declined. Revenues increased because volume gains exceeded the price decline, which indicates that the market for internet ads keeps growing. But this makes 15 straight quarters of price declines for Google. Due to this long series of small declines, the average price of Google’s ads (cost per click) has declined 70%* since Q3 2011!

While this is a miraculous example of what economists call demand elasticity, one has to wonder how long growth will continue to outpace price degradation. At some point the marginal growth in demand may not equal the marginal decline in pricing. Should that happen, revenues will start going down rather than up.

Part of what drives this price/growth effect has been the creation of programmatic ad buying, which allows Google to place more ads in more specific locations for advertisers via such automated products as AdMob, AdExchange and DoubleClick Bid Manager. But such computerized ad buying relies on ever more content going onto the web, as well as ever more consumption by internet users.

Further, Google’s revenues are almost entirely search-based advertising, and Google dominates this category. But this is largely a PC-related sale. Today 67.5% of Google ad revenue is from PC searches, while only 32.5% is from mobile searches. Due to this revenue skew, and the fact that people do more mobile interaction via apps, messaging apps and social media than browser, search ad growth has fallen considerably. What was a 24% year over year growth rate in Q1 2012 has dropped to more like 15% for the last 8 quarters.

So while the market today is growing, and Google is making more money, it is possible to see that the growth is slowing. And Google’s efforts to create mobile ad sales outside of search has largely failed, as witnessed by the recent death of Google+ as competition for Twitter or Facebook. It is the market shift, to mobile, which creates the greatest threat to Google’s ability to grow; certainly at historical rates.

Simultaneously, Facebook’s announcements showed just how strongly it is continuing to dominate both social media and mobile, and thus generate higher revenues and profits with outstanding growth. The #1 site for social media and messenger apps is Facebook, by quite a large margin. But, Facebook’s 2014 acquisition of What’sApp is now #2. WhatsApp has doubled its monthly active users (MAUs) just since the acquisition, and now reaches 800million. Growth is clearly accelerating, as this is from a standing start in 2011.

Facebook Messenger at #3, just behind WhatsApp. And #5 is Instagram, another Facebook acquisition. Altogether 4 of the top 5 sites, and the ones with greatest growth on mobile, are Facebook. And they total over 3billion MAUs, growing at over 300million new MAUs/month. Thus Facebook has already emerged as the dominant force, with the most users, in the fast-growing, accelerating, mobile and app sectors. (Just as Google did in internet search a decade ago, beating out companies like Yahoo, Ask Jeeves, etc.)

Google is moving rapidly to monetize this user base. From nothing in early 2012, Facebook’s mobile revenue is now $2.5B/quarter and represents 67% of global revenue (the inverse of Google’s revenues.) Further, Facebook is now taking its own programmatic ad buying tool, Atlas, to advertisers in direct competition with Google. Only Atlas places ads on both social media and internet browser pages – a one-two marketing punch Google has not yet cracked.

Google’s $17.3B Q1 2015 revenue is 30 times the revenue of Facebook. There is no doubt Google is growing, and generating enormous profits. But, for long-term investors, growth is slowing and there is reason to be concerned about the long term growth prospects of Google as the market shifts toward more social and more mobile. Google has failed to build any substantial revenues outside of search, and has had some notable failures recently outside its core markets (Google + and Google Glass.) Just how long Google will continue growing, and just how fast the market will shift is unclear. Technology markets have shown the ability to shift a lot faster than many people expected, leaving some painful losers in their wake (Dell, HP, Sun Microsystems, Yahoo, etc.)

Meanwhile, Facebook is squarely positioned as the leader, without much competition, in the next wave of market growth. Facebook is monetizing all things social and mobile at a rapid clip, and wisely using acquisitions to increase its strength. As these markets continue on their well established trends it is hard to be anything other than significantly optimistic for Facebook long-term.

* 1x .93 x .88 x .84 x .85 x .94 x .96 x .94 x .93 x .89 x .91 x .94 x .98 x .97 x .95 x .93 = .295

by Adam Hartung | Apr 25, 2015 | Defend & Extend, Food and Drink, In the Rapids, In the Swamp, Innovation, Leadership, Transparency

If you don’t drink gin you may not know the brand Tanqueray, a product owned by Diageo. But Tanqueray has been around for almost 190 years, going back to the days when London Dry Gin was first created. Today Tanqueray is one of the most dominant gin brands in the world, and the leading brand in the USA.

But gin is not a growth category. And Tanqueray, despite its great product heritage and strong brand position, has almost no growth prospects.

But gin is not a growth category. And Tanqueray, despite its great product heritage and strong brand position, has almost no growth prospects.

Any product that doesn’t grow sales cannot generate profits to spend on brand maintenance. Firstly, if due to nothing more than inflation, costs always go up over time. It takes rising sales to offset higher costs. Additionally, small competitors can niche the market with new products, cutting into leader sales. And competitors will undercut the leader’s price to steal volume/share in a stagnant market, causing margin erosion.

Category growth stalls are usually linked to substitute products stealing share in a larger definition of the marketplace. For example sales of laptop/desktop PCs stalled because people are now substituting tablets and smartphones. The personal technology market is growing, but it is in the newer product category stealing sales from the older product category.

This is true for gin sales, because older drinkers – who dominate today’s gin market – are drinking less spirits, and literally dying from old age. In the overall spirits market, younger liquor drinkers have preferred vodkas and flavored vodkas which are “smoother,” sweeter, and perceived as “lighter.”

So, what is a brand manager to do? Simply let trends obsolete their product line? Milk their category and give up money for investing somewhere else?

That may sound fine at a corporate level, where category portfolios can be managed by corporate vice presidents. But if you’re a brand manager and you want to become a future V.P., managing declining product sales will not get you into that promotion. And defending market share with price cuts, rebates and deals will cut into margin, ruin the brand position and likely kill your marketing career.

Keith Scott is the Senior Brand Manager for Tanqueray, and his team has chosen to regain product growth by using sustaining innovations in a smart way to attract new customers into the gin category. They are looking beyond the currently dwindling historical customer base of London Dry Gin drinkers, and working to attract new customers which will generate category growth and incremental Tanqueray sales. He’s looking to build the brand, and the category, rather than get into a price war.

Building on demographic trends, Tanqueray’s brand management is targeting spirit drinkers from 28-38. Three new Tanqueray brand extensions are being positioned for greatest appeal to increasingly adult tastes, while offering sophistication and linkage to one of the longest and strongest spirits brands.

#1 – Tanqueray Rangpur is a highly citrus-flavored gin taking a direct assault on flavored vodkas. Although still very much a gin, with its specific herb-based taste, Rangpur adds a hefty, and uniquely flavored, dose of lime. This makes for a fast, easy to prepare gin and tonic or lime-based gimlet – 2 classic cocktails that have their roots in England but have been popular in the US since before prohibition. And, in defense of the brand, Rangpur is priced about 10-20% higher than London Dry.

#1 – Tanqueray Rangpur is a highly citrus-flavored gin taking a direct assault on flavored vodkas. Although still very much a gin, with its specific herb-based taste, Rangpur adds a hefty, and uniquely flavored, dose of lime. This makes for a fast, easy to prepare gin and tonic or lime-based gimlet – 2 classic cocktails that have their roots in England but have been popular in the US since before prohibition. And, in defense of the brand, Rangpur is priced about 10-20% higher than London Dry.

#2 – Tanqueray Old Tom and Tanqueray Milacca appeal to the demographic that loves specialty, crafted products. The “craft” product movement has grown dramatically, and nowhere more powerfully than amongst 28-42 year old beer drinkers. Old Tom and Milacca leverage this trend. Both are “retro” products, harkening to gins over 100 years ago. They are made in small batches and have limited availability. They are targeted at the consumer that wants something new, unique, unusual and yet tied to old world notions of hand-made production and high quality. These craft products are priced 25-35% higher than traditional London Dry.

#2 – Tanqueray Old Tom and Tanqueray Milacca appeal to the demographic that loves specialty, crafted products. The “craft” product movement has grown dramatically, and nowhere more powerfully than amongst 28-42 year old beer drinkers. Old Tom and Milacca leverage this trend. Both are “retro” products, harkening to gins over 100 years ago. They are made in small batches and have limited availability. They are targeted at the consumer that wants something new, unique, unusual and yet tied to old world notions of hand-made production and high quality. These craft products are priced 25-35% higher than traditional London Dry.

#3 – Tanqueray No. 10 is a “super-premium” product pointed at the customer who wants to project maximum sophistication and wealth. No 10 uses a special manufacturing process creating a uniquely smooth and slightly citrus flavor. But this process loses 40% of the product to “tailings” compared to the industry standard 10% loss. No. 10 is the high-end defense of the Tanqueray brand (a “top shelf” product as its known in the industry) priced 75-90% higher than London Dry.

No. 10 is being promoted with “invitation only” events being held in major U.S. cities such as New York, Chicago and Atlanta. No. 10 “trunk events” bring in some of the hottest, newest designers to showcase the latest in apparel trends, accompanied by hot, new musical talent. No. 10 is associated with the sophistication of super-premium brands – individualized and rare products – in a members-only environment. Targeted at the primary demographic of 28-38, No. 10 events are designed to lure these consumers to this product they otherwise might overlook .

Rather than addressing their gin category growth stall with price cuts and other sales incentives, which would lead to brand erosion, price erosion, and margin erosion, the Tanqueray brand team is leveraging trends to bring new consumers to their category and generate profitable growth. These innovative brand extensions actually build brand value while leveraging identifiable market trends. Notice that all these sustaining innovations are actually priced higher than the highest volume London Dry core product, thus augmenting price – and hopefully margin.

Too often leaders see their market stagnate and use that as an excuse lower expectations and accept sales decline. They don’t look beyond their core market for new customers and sources of growth. They react to competition with the blunt axe of pricing actions, seeking to maintain volume as margins erode and competition intensifies. This accelerates product genericization, and kills brand value.

The Tanqueray brand team demonstrates how critical sustaining innovation can be for maintaining growth at all levels of an organization. Even the level of a single product or brand. They are using sustaining innovations to lure in new customers and grow the brand umbrella, while growing the category and achieving desired price realization. This is a lesson many brands, and companies, should emulate.

Trend 1- Low minimum wages & “Wage gap” issues remain a big deal

Trend 1- Low minimum wages & “Wage gap” issues remain a big deal