by Adam Hartung | Jan 15, 2014 | Current Affairs, Leadership

The S&P 500 had a great 2013. Up 29.7% – its best performance since 1997. The Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA) ended the year up 26.5% – its best performance since 1995. And this happened as economic growth lowered the unemployment rate to 6.7% in December – the lowest rate in 5 years. And overall real estate had double-digit price gains, lowering significantly the number of underwater mortgages.

But if we go back to the beginning of 2013, most Wall Street forecasters were predicting a very different outcome. Long suffering bear Harry Dent predicted a stock crash in 2013 that would last through 2014, and ongoing cratering in real estate values. And bear Gina Martin Adams of Wells Fargo Securities predicted a market decline in 2013, a forecast she clung to and fully supported, despite a rising market, when predicting an imminent crash in September. Morgan Stanley’s Adam Parker also predicted a flat market, as did UBS analyst Jonathan Golub.

How could professionals who are paid so much money, have so many resources and the backing of such outstanding large and qualified institutions be so wrong?

An over-reliance on quantitative analysis, combined with using the wrong assumptions.

The conventional approach to Wall Street forecasting is to use computers to amass enormously complex spreadsheets combining reams of numbers. Computer models are built with thousands of inputs, and tens of millions of data points. Eventually the analysts start to believe that the sheer size of the models gives them validity. In the analytical equivalent of “mine is bigger than yours” the forecasters rely on their model’s complexity and sheer size to self-validate their output and forecasts.

In the end these analysts come up with specific forecast numbers for interest rates, earnings, momentum indicators and multiples (price/earnings being key.) Their faith that the economy and market can be reduced to numbers on spreadsheets leads them to similar faith in their forecasts.

But, numbers are often the route to failure. In the late 1990s a team of Wall Street traders and Nobel economists became convinced their ability to model the economy and markets gave them a distinct investing advantage. They raised $1billion and formed Long Term Capital (LTC) to invest using their complex models. Things worked well for 3 years, and faith in their models grew as they kept investing greater amounts.

But then in 1998 downdrafts in Asian and Russian markets led to a domino impact which cost Long Term Capital $4.6B in losses in just 4 months. LTC lost every dime it ever raised, or made. But worse, the losses were so staggering that LTC’s failure threatened the viability of America’s financial system. The banks, and economy, were saved only after the Federal Reserve led a bailout financed by 14 of the leading financial institutions of the time.

Incorrect assumptions played a major part in how Wall Street missed the market prediction for 2013. All models are based on assumptions. And, as Peter Drucker famously said, “if you get the assumptions wrong everything you do thereafter will be wrong as well” — regardless how complex and vast the models.

Conventional wisdom held that conservative economic policies underpin market growth, and the more liberal Democratic fiscal policies combined with a liberal federal reserve monetary program would bode poorly for investors and the economy in 2013. These deeply held assumptions were, of course, reinforced by a slew of conservative commentators that supported the notion that America was on the brink of runaway inflation and economic collapse. The BIAS (Beliefs, Interpretations, Assumptions and Strategies) of the forecasters found reinforcement almost daily from the rhetoric on CNBC, Bloomberg, Fox News and other programs widely watched by business people from Wall Street to Main Street.

Interestingly, when Obama was re-elected in 2012 a not-so-well-known investment firm in Columbus, OH – far from Wall Street – took an alternative look at the data when forecasting 2013. Polaris Financial Partners took a deep dive into the history of how markets perform when led by traditional conservative vs. liberal policies and reached the startling conclusion that Obama’s programs, including the Affordable Care Act, would actually spur investment, market growth, jobs and real estate! They had forecast a double digit increase in all major averages for 2012 and extended that same double digit forecast into 2013 – far more optimistic than anyone on Wall Street.

CEO Bob Deitrick and partner Steven Morgan concluded that the millenium’s first decade had been lost. Despite Republican leadership, the eqity markets were, at best, sideways. There were fewer people actually working in 2008 than in 2000; a net decrease in jobs. After a near-collapse in the banking system, due to deregulated computer-model based trading in complex derivatives, real estate and equity prices had collapsed.

“Fourteen years of stock market gains were wiped out in 17 months from October, 2007 to March, 2009” lamented Deitrick.

Polaris Partners concluded the situation was eerily similar to the 1920s at the end of Hoover’s administration. A situation which was eventually resolved via Keynesian policies of increased fiscal spending while interest rates were low, and federal reserve intervention to both expand the money supply and increase the velocity of money under Republican Fed chief Marriner Eccles and Democratic President Franklin Roosevelt.

While most people conventionally think that tax cuts led to economic growth during the Reagan administration, Polaris Financial turned that assumption upside down and put the biggest positive economic impact on the roll-back of tax cuts a year after being pushed by Reagan and passing Congress. Their analysis of the 1980 recovery focused on higher defense and infrastructure spending (fiscal policy,) a massive increase in debt (the largest peacetime debt increase ever) coupled with a more balanced tax code post-TEFRA.

Thus, eschewing complex econometric models, elaborately detailed spreadsheets of earnings and rolling momentum indicators, Polaris Financial focused instead on identifying the assumptions they believeed would most likely drive the economy and markets in 2013. They focused on the continuation of Chairman Bernanke’s easy monetary policy, and long-term fiscal policies designed to funnel money into investments which would incent job creation and GDP growth leading to an improvement in house values, and consumer spending, while keeping interest rates at historically low levels. All of which would bode extremely well for thriving equity markets.

The vitriol has been high amongst those who support, and those who oppose, the economic policies of Obama’s administration since 2008. But vitriol does not support, nor replace, good forecasting. Too often forecasters predict what they want to happen, what they hope will happen, based upon their view of history, their traing and background, and their embedded assumptions. They believe in the certainty of long-held assumptions, and forecast from that base.

But as Polaris Financial pointed out, in beating every major Wall Street firm over the last 2 years, good forecasting relies on looking carefully at historical outcomes, and understanding the context in which those results happened. Rather than relying on an interpretation of the outcome,they looked instead at the facts and the situation; the actions and the outcomes in its context. In an economy, everything is relative to the context. There are no absolute programs that are universally the right thing to do. Every policy action, and every monetary action, is dependent upon initial conditions as well as the action itself.

Too few forecasters take into account both the context as well as the action. And far too few do enough analysis of assumptions, preferring instead to rely on reams of numerical analysis which may, or may not, relate to the current situation. And are often linked to assumptions underlying the model’s construction – assumptions which could be out of date or simply wrong.

The folks at Polaris Financial Partners remain optimistic about the economy and markets for the next two years. They point out that unemployment has dropped faster under Obama, and from a much higher level, than during the Reagan administration. They see the Affordable Care Act opening more flexibility for health care, creating a rise in entrepreneurship and innovation (especially biotechnology) that will spur economic growth. Deitrick and Morgan see tax programs, and rising minimum wage trends, working toward better income balancing, and greater monetary velocity aiding GDP growth. Their projection is for improving real estate values, jobs growth, and minimal inflation leading to higher indexes – such as 20,000 on the DJIA and 2150 on the S&P.

Bob Deitrick co-authored, with Lew Goldfarb, “Bulls, Bears and the Ballot Box” in 2012 analyzing Presidential economic policies, Federal Reserve policies and stock market performance.

by Adam Hartung | Jan 8, 2014 | Current Affairs, In the Rapids, Innovation, Leadership, Web/Tech

Most investors really aren’t. They are traders. They sell too fast, and make too many transactions. That’s why most small “investors” don’t do as well as the market averages. In fact, most don’t even do as well as if they simply put money into certificates of deposit or treasury bills.

I subscribe to the idea you should be able to invest in a company, and then simply forget about it. Whether you invest $10 or $100,000, you should feel confident when you buy a stock that you won’t touch it for 3, 5 or even 10 years. Let the traders deal with volatility, just wait and let the company do its thing and go up in value. Then sometime down the road sell it for a multiple of what you paid.

That means investing in big trends. Find a trend that is long-lasting, perhaps permanent, and invest in the leader. Then let the trend do all the work for you.

Imagine you bought AT&T in the 1950s as communication was about to proliferate and phones went into every business and home. Or IBM in the 1960s as computer technology overtook slide rules, manual databases and bookkeeping. Microsoft in the 1980s as personal computers became commonplace. Oracle in the 1990s as applications were built on relational databases. Google, Amazon and Apple in the last decade as people first moved to the internet in droves, and as mobile computing became the next “big thing.”

In each case investors put their money in a big trend, and invested in a leader far ahead of competitors with a strong management team and product pipeline. Then they could forget about it for a few years. All of these went up and down, but over time the vicissitudes were obliterated by long-term gains.

Today the biggest trend is social media. While many people still decry its use, there is no doubt that social media platforms are becoming commonplace in how we communicate, look for information, share information and get a lot of things done. People inherently like to be social; like to communicate. They trust referrals and comments from other people a lot more than they trust an ad – and often more than they trust conventional media. Social media is the proverbial fast flowing river, and getting in that boat is going to take you to a higher value destination.

And the big leader in this trend is Facebook. Although investors were plenty upset when Facebook tumbled after its IPO in 2012, if you had simply bought then, and kept buying a bit each quarter, you’d already be well up on your investment. Almost any purchase made in the first 12 months after the IPO would now have a value 2 to 3 times the acquisition price – so a 100% to 200% return.

But, things are just getting started for Facebook, and it would be wrong to think Facebook has peaked.

Few people realize that Facebook became a $5B revenue company in 2012 – growing revenue 20X in 4 years. And revenue has been growing at 150% per year since reaching $1B. That’s the benefit of being on the “big trend.” Revenues can grow really, really, really fast.

And the market growth is far from slowing. In 2013 the number of U.S. adults using Facebook grew to 71% from 67% in 2012. And that is 3.5 times as often as they used Linked-In or Twitter (22% and 18%.) And Facebook is not U.S. user dependent. Europe, Asia and Rest-of-World have even more users than the USA. ROW is 33% bigger than the USA, and Facebook is far from achieving saturation in these much higher population markets.

Advertisers desiring to influence these users increased their budgets 40% in 2013. And that is sure to grow as users and their interactions climb. According to Shareaholic, over 10% of all internet referrals come from Facebook, up from 7% share of market the previous year. This is 10 times the referral level of Twitter (1%) and 100 times the levels of Linked in and Google+ (less than .1% each.) Thus, if an advertiser wants to users to go to its products Facebook is clearly the place to be.

Facebook acquires more of these ad dollars than all of its competition combined (57% share of market,) and is 4 times bigger than competitors Twitter and YouTube (a Google business.) The list of Grade A advertisers is long, including companies such as Samsung ($100million,) Proctor & Gamble ($60million,) Microsoft ($35million,) Amazon, Nestle, Unilever, American Express, Visa, Mastercard and Coke – just to name a few.

And Facebook has a lot of room to grow the spending by these companies. Google, the internet’s largest ad revenue generator, achieves $80 of ad revenue per user. Facebook only brings in $13/user – less than Yahoo ($18/user.) So the opportunity for advertisers to reach users more often alone is a 6x revenue potential – even if the number of users wasn’t growing.

But on top of Facebook’s “core” growth there are new revenue sources. Since buying revenue-free Instagram, Facebook has turned it into what Evercore analysts estimate will be a $340M revenue in 2014. And as its user growth continues revenue is sure to be even larger in future years.

Even a larger opportunity for growth is the 2013 launched Facebook Ad Exchange (FBX) which is a powerful tool for remarketing unused digital ad space and targeting user behavior – even in mid-purchase. According to BusinessInsider.com FBX already sells to advertisers millions of ads every second – and delivers up billions of impressions daily. All of which is happening in real-time, allowing for exponential growth as Facebook and advertisers learn how to help people use social media to make better purchase decisions. FBX is currently only a small fraction of Facebook revenue.

Stock investing can seem like finding a needle in a haystack. Especially to small investors who have little time to do research. Instead of looking for needles, make investing easier. Eschew complicated mathematical approaches, deep portfolio theory and reams of analyst reports and spreadsheets. Invest in big trends that are growing, and the leaders building insurmountable market positions.

In 2014, that means buy Facebook. Then see where your returns are in 2017.

by Adam Hartung | Dec 19, 2013 | Current Affairs, Leadership

Everyone has a stake in America’s big, public corporations. Either as an investor, employee, customer, supplier or community leader. So how these corporations perform is a big deal for all of us.

Unfortunately, we’ve had all too many corporations that have their problems. But, amazingly, we see little change in the CEO, or CEO compensation. When one of the USA‘s largest employers, McDonald’s, uses its hotline to tell low-paid employees they should avoid breaking open Christmas gift boxes, and instead return gifts for cash to buy gas and groceries, it’s not a bad idea to take a look at top executive pay. And with so many people still looking for work, and unemployment for people under 25 at something like 15%, there is an ongoing question as to whether CEOs are being held accountable or simply granted their jobs regardless of performance.

Given that Scrooge was a banker, why not start by looking at bank CEOs? And who better to glance at than the ultra-high profile Jamie Dimon, CEO and Chairman of JPMorganChase.

In 2012 Mr. Dimon told us there were really no problems in the JPMC derivatives business. We later learned that – oops – the unit did actually lose something like $6billion. Mr. Dimon was nice enough to admit this was more than a “templest in a teapot,” and eventually apoligized. He asked us to all realize that JPMC is really big, and mistakes will happen. Just forget about it and move on he recommended.

But in 2013 the regulators said “not so fast” and fined JPMC close to $1billion for failure to properly safeguard the public interest. The Board felt compelled to reflect on this misadventure and cut Mr. Dimon’s pay in half to a paltry $18.7million. That means in the year when things went $7billion wrong, he was paid nearly $37million – and the penalty was to subsequently receive only $19million. Thus his total compensation for 2 years, during which $7billion evaporated from the bank, was (roughly) $50M.

It appears unlikely anyone will be returning gifts to buy ham and beans in the Dimon household this year.

Mr. Dimon was spanked by the Board, and he is no longer the most highly paid CEO in the banking industry. That 2013 title goes to Wells Fargo CEO John Stumpf, who received about $23M. Wells Fargo is still sorting out the mess from all those bad mortgages which have left millions of Americans with foreclosures, bankruptcies, costly short-sales and mortgages greater than the home value. But, hotlines are now in place and things are getting better!

CEO compensation is interesting because it is all relative. Pay is minimally salary – never more than $1M (although that alone is a really big number to most people.) Bonuses make up most of the compensation,based on relative metrics tied to comparisons with industry peers. So, if an industry does badly and every company does poorly the CEOs still get paid their bonuses. You don’t have to be a Steve Jobs or Jeff Bezos with new insights, lots of growth, great products and margins to be paid a lot. Just don’t do a whole lot worse than some peer group you are compared against.

Which then brings us to the whole idea of why CEOs that make big mistakes – like the whopper at JPMC – so easily keep their jobs. Would a McDonald’s cashier that missed handing out change by $7 (1 one-billionth the JPMC mistake) likely be paid well – or fired? What about a JPMC bank teller? Yet, even when things go terribly wrong we rarely see a CEO lose their job.

During this shopping season, just look at Sears. Ed Lampert cut his pay to $1 in 2013. Hooray! But this did not help the company.

Sears and Kmart business is so bad CEO Lampert changed strategy in 2013 to selling profitable stores rather than more lawn mowers and hand tools in order to keep the company alive. Yet, as more employees leave, suppliers risk being repaid, communities lose their stores and retail jobs and tax base, Mr. Lampert remains Sears Holdings CEO. We accept that because he owns so much stock he has the “right” to remain CEO.

Perhaps Mr. Lampert deserves a visit from his own personal Jacob Marley, who might make him realize that there is more to life (and business) than counting cash flow and seeking lower cost financing options. Mr. Lampert can arise each morning before dawn to browbeat employees via conference webinars, and micromanage a losing business. But it leaves him sounding a lot like Scrooge. Meanwhile those behaviors have not stopped Sears and KMart from losing all market relevancy, and spiraling toward failure.

CEO pay-to-worker ratios have increased 1,000% since 1950. (How’s that for a “relative” metric?) Today the average CEO makes 200 times the company’s workforce (the top 100 make 300 times as much – and the CEO of Wal-Mart has a pension 6,182 times that of the average employee.) Is it any wonder so many investors, employees, customers, suppliers and community leaders are paying so much attention to CEO performance – and pay?

We are all thankful for the good CEO that develops long-range plans, spends time investing in growth projects, developing employees, increasing revenue and margins while expanding the communities in which the company lives and works. It just doesn’t happen often enough.

This Christmas, as many before, as we look at our portfolios, paychecks, pensions, product quality, service quality and communities too many of us wish far too often for better CEOs, and compensation really aligned with long-term performance for all constituencies.

by Adam Hartung | Dec 3, 2013 | Current Affairs, Leadership, Web/Tech

“A horse, a horse, my Kingdom for a Horse” King Richard cried out just before he was murdered (Richard III by Billy Shakespeare ~ 1592.)

King Richard of England was really, really unpopular. He was accused of ascending to the throne via various Michiavellian behaviors. Eventually he was trapped on the battlefield by his enemies, his horse was slain, and he uttered the above line – metaphorically begging for a way out of the trapped world that was his kingdom. He didn’t get the horse – and he died.

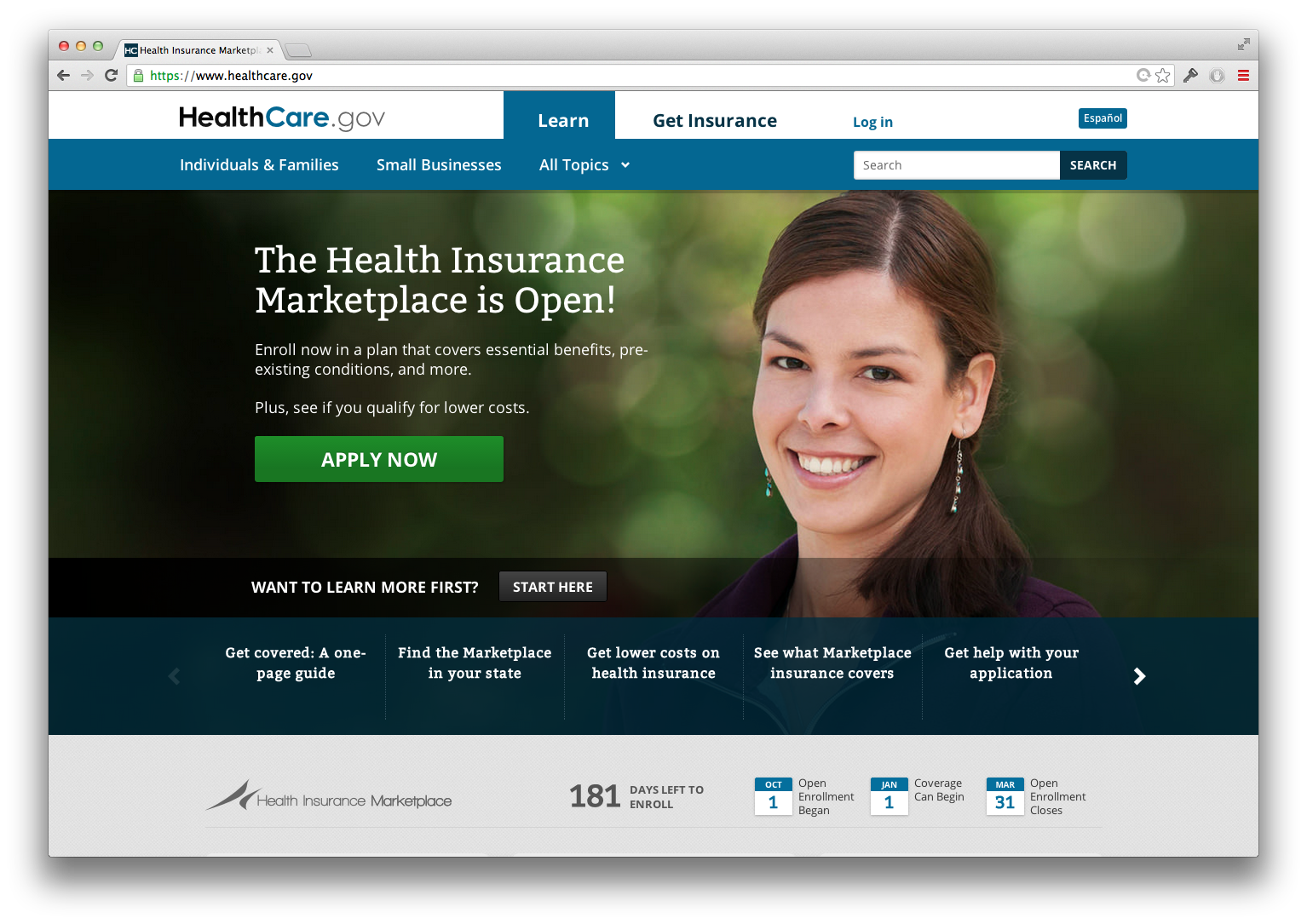

After over 20 years of fighting about health care the U.S. Congress passed the Affordable Care Act and the President signed it into law in 2010. About the only agreement in the country was that the ACA appealed to almost no one due to the compromises required to get it passed. It was fought by wide ranging constituencies, until in 2012 the Supreme Court upheld the law.

But not even that was the end of the fight, because in October, 2013 Congress shut down the government as groups fought about whether the act would receive any funding to implement its own provisions. Eventually an agreement was reached, the government re-opened, and it looked like the ACA was going into practice.

Oh, but wait…

In today’s world everyone uses the internet. Face-to-face meetings are largely gone, and forests by the score are being saved as we refuse to use paper when a digital screen will accomplish our tasks. So it only made sense that when the U.S. population was to sign up for the benefits of this new law they would do so on the World Wide Web.

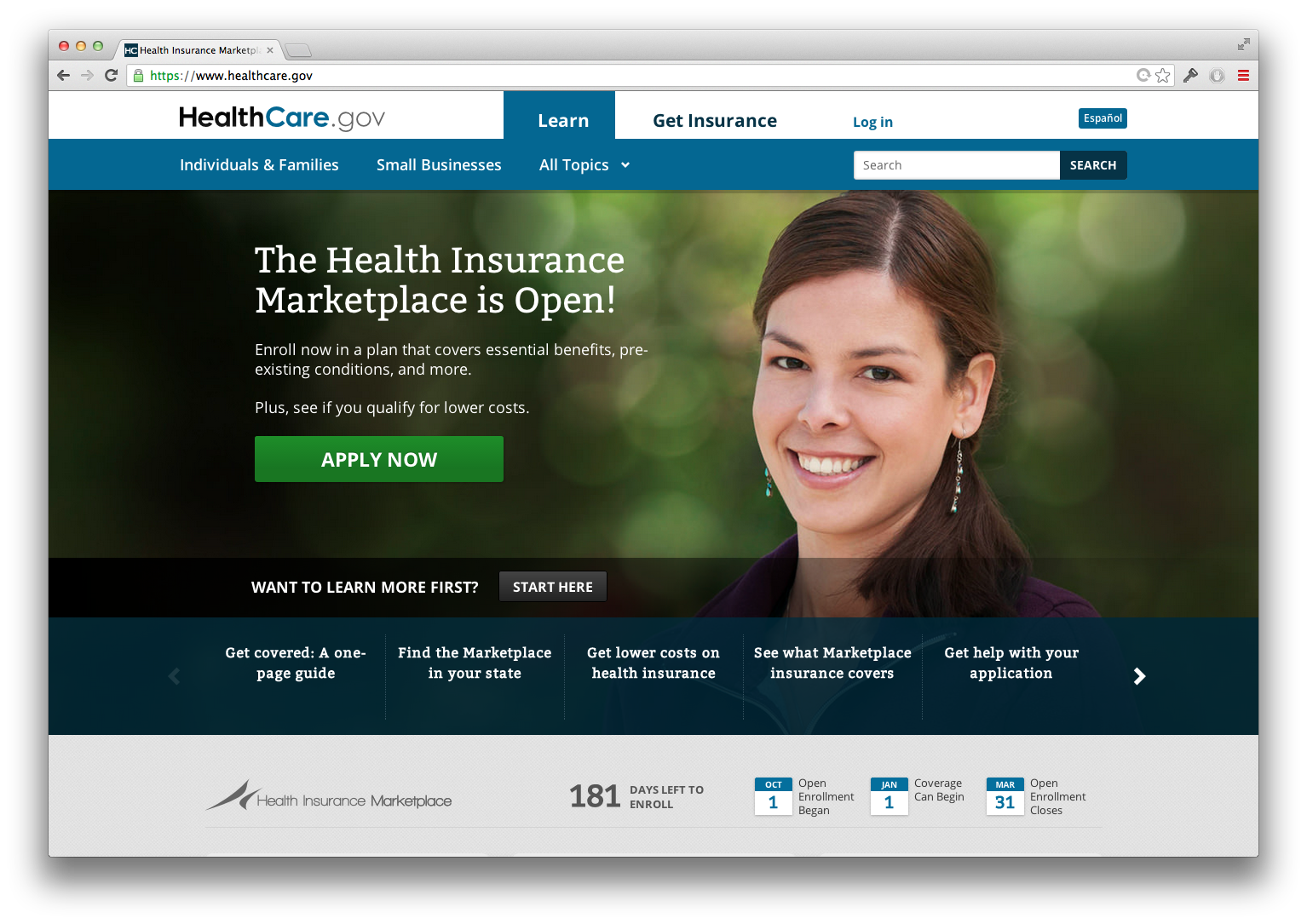

Folks would buy health insurance just like they buy books and clothes, and download movies, from a web site. Billions of transactions have happened over the web the last decade. Why, Google alone does over 5 billion searches each and every day. So it seemed easily practical, and doable, for implementation to be as easy as opening a new web site. We all expected that come November we’d simply hit the search button, go to the web site, price out the options and make our health insurance decisions.

Of course we all know how that worked out. Or didn’t. The site didn’t work for spit. Apple may be able to track about a million apps on its site, and it seems able to deliver about 4 million per day at an average price of about a buck. But the U.S. government web site – after spending over $400million (maybe even $1B) – couldn’t seem to process but a few thousand applications a day. So Congressional hearings started – cries for firing Secretary Sebelius rang out – and President Obama’s favorability plummeted faster than the failed effort messages came up in browsers at Healthcare.gov.

You could almost hear the President on the steps of the White House “A web site, a working web site, my Presidency for a working web site.”

There was a Chicago mayor who lost an election because he couldn’t clear the streets of snow. Something as simple as removing snow in a 1979 blizzard overtook everything Mayor Bilandic’s administration did, and wanted to do, for his great city. When Chicagoans couldn’t access their streets for 3 days they “threw the bastard out” by electing a new candidate (Jane Byrne) in the next primary – and she went on to be the next mayor.

And the only thing anyone remembers about Mayor Bilandic was he didn’t get the snow off the streets.

This lesson is not lost on any local mayor. You can have grand plans, and vision, but if you can’t keep the streets clean you get thrown out.

We’ve entered a new era of political expectations. Citizens now expect their politicians to build and operate functional web sites. They expect their government to do as least as good a job as private industry at everything digital. And if politicians, or administrators, flub a web implementation it can have signficant, damaging implications.

Failure to build a functional web site, meeting the average person’s expectations, is a terrible, terrible falure these days. Perhaps enough to lose the voters’ trust. Perhaps enough to breath new life into those who want to overturn your “landmark legislation.” And perhaps enough to kill your place in history.

by Adam Hartung | Nov 22, 2013 | Current Affairs, Defend & Extend, In the Whirlpool, Leadership, Television

Do you really think in 2020 you’ll watch television the way people did in the 1960s? I would doubt it.

In today’s world if you want entertainment you have a plethora of ways to download or live stream exactly what you want, when you want, from companies like Netflix, Hulu, Pandora, Spotify, Streamhunter, Viewster and TVWeb. Why would you even want someone else to program you entertainment if you can get it yourself?

Additionally, we increasingly live in a world unaccepting of one-way communication. We want to not only receive what entertains us, but share it with others, comment on it and give real-time feedback. The days when we willingly accepted having information thrust at us are quickly dissipating as we demand interactivity with what comes across our screen – regardless of size.

These 2 big trends (what I want, when I want; and 2-way over 1-way) have already changed the way we accept entertaining. We use USB drives and smartphones to provide static information. DVDs are nearly obsolete. And we demand 24×7 mobile for everything dynamic.

Yet, the CEO of Charter Cable company wass surprised to learn that the growth in cable-only customers is greater than the growth of video customers. Really?

It was about 3 years ago when my college son said he needed broadband access to his apartment, but he didn’t want any TV. He commented that he and his 3 roommates didn’t have any televisions any more. They watched entertainment and gamed on screens around his apartment connected to various devices. He never watched live TV. Instead they downloaded their favorite programs to watch between (or along with) gaming sessions, picked up the news from live web sites (more current and accurate he said) and for sports they either bought live streams or went to a local bar.

To save money he contacted Comcast and said he wanted the premier internet broadband service. Even business-level service. But he didn’t want TV. Comcast told him it was impossible. If he wanted internet he had to buy TV. “That’s really, really stupid” was the way he explained it to me. “Why do I have to buy something I don’t want at all to get what I really, really want?”

Then, last year, I helped a friend move. As a favor I volunteered to return her cable box to Comcast, since there was a facility near my home. I dreaded my volunteerism when I arrived at Comcast, because there were about 30 people in line. But, I was committed, so I waited.

The next half-hour was amazingly instructive. One after another people walked up to the window and said they were having problems paying their bills, or that they had trouble with their devices, or wanted a change in service. And one after the other they said “I don’t really want TV, just internet, so how cheaply can I get it?”

These were not busy college students, or sophisticated managers. These were every day people, most of whom were having some sort of trouble coming up with the monthly money for their Comcast bill. They didn’t mind handing back the cable box with TV service, but they were loath to give up broadband internet access.

Again and again I listened as the patient Comcast people explained that internet-only service was not available in Chicagoland. People had to buy a TV package to obtain broad-band internet. It was force-feeding a product people really didn’t want. Sort of like making them buy an entree in order to buy desert.

As I retold this story my friends told me several stories about people who banned together in apartments to buy one Comcast service. They would buy a high-powered router, maybe with sub-routers, and spread that signal across several apartments. Sometimes this was done in dense housing divisions and condos. These folks cut the cost for internet to a fraction of what Comcast charged, and were happy to live without “TV.”

But that is just the beginning of the market shift which will likely gut cable companies. These customers will eventually hunt down internet service from an alternative supplier, like the old phone company or AT&T. Some will give up on old screens, and just use their mobile device, abandoning large monitors. Some will power entertainment to their larger screens (or speakers) by mobile bluetooth, or by turning their mobile device into a “hotspot.”

And, eventually, we will all have wireless for free – or nearly so. Google has started running fiber cable in cities including Austin, TX, Kansas City, MO and Provo, Utah. Anyone who doesn’t see this becoming city-wide wireless has their eyes very tightly closed. From Albuquerque, NM to Ponca City, OK to Mountain View, CA (courtesy of Google) cities already have free city-wide wireless broadband. And bigger cities like Los Angeles and Chicago are trying to set up free wireless infrastructure.

And if the USA ever invests in another big “public works infrastructure” program will it be to rebuild the old bridges and roads? Or is it inevitable that someone will push through a national bill to connect everyone wirelessly – like we did to build highways and the first broadcast TV.

So, what will Charter and Comcast sell customers then?

It is very, very easy today to end up with a $300/month bill from a major cable provider. Install 3 HD (high definition) sets in your home, buy into the premium movie packages, perhaps one sports network and high speed internet and before you know it you’ve agreed to spend more on cable service than you do on home insurance. Or your car payment. Once customers have the ability to bypass that “cable cost” the incentive is already intensive to “cut the cord” and set that supplier free.

Yet, the cable companies really don’t seem to see it. They remain unimpressed at how much customers dislike their service. And respond very slowly despite how much customers complain about slow internet speeds. And even worse, customer incredulous outcries when the cable company slows down access (or cuts it) to streaming entertainment or video downloads are left unheeded.

Cable companies say the problem is “content.” So they want better “programming.” And Comcast has gone so far as to buy NBC/Universal so they can spend a LOT more money on programming. Even as advertising dollars are dropping faster than the market share of old-fashioned broadcast channels.

Blaming content flies in the face of the major trends. There is no shortage of content today. We can find all the content we want globally, from millions of web sites. For entertainment we have thousands of options, from shows and movies we can buy to what is for free (don’t forget the hours of fun on YouTube!)

It’s not “quality programming” which cable needs. That just reflects industry deafness to the roar of a market shift. In short order, cable companies will lack a reason to exist. Like land-line phones, Philco radios and those old TV antennas outside, there simply won’t be a need for cable boxes in your home.

Too often business leaders become deaf to big trends. They are so busy executing on an old success formula, looking for reasons to defend & extend it, that they fail to evaluate its relevancy. Rather than listen to market shifts, and embrace the need for change, they turn a deaf ear and keep doing what they’ve always done – a little better, with a little more of the same product (do you really want 650 cable channels?,) perhaps a little faster and always seeking a way to do it cheaper – even if the monthly bill somehow keeps going up.

But execution makes no difference when you’re basic value proposition becomes obsolete. And that’s how companies end up like Kodak, Smith-Corona, Blackberry, Hostess, Continental Bus Lines and pretty soon Charter and Comcast.

by Adam Hartung | Nov 6, 2013 | Defend & Extend, Innovation, Leadership, Web/Tech

Can you believe it has been only 12 years since Apple introduced the iPod? Since then Apple’s value has risen from about $11 (January, 2001) to over $500 (today) – an astounding 45X increase.

With all that success it is easy to forget that it was not a “gimme” that the iPod would succeed. At that time Sony dominated the personal music world with its Walkman hardware products and massive distribution through consumer electronics chains such as Best Buy, and broad-line retailers like Wal-Mart. Additionally, Sony had its own CD label, from its acquisition of Columbia Records (renamed CBS Records,) producing music. Sony’s leadership looked impenetrable.

But, despite all the data pointing to Sony’s inevitable long-term domination, Apple launched the iPod. Derided as lacking CD quality, due to MP3’s compression algorithms, industry leaders felt that nobody wanted MP3 products. Sony said it tried MP3, but customers didn’t want it.

All the iPod had going for it was a trend. Millions of people had downloaded MP3 songs from Napster. Napster was illegal, and users knew it. Some heavy users were even prosecuted. But, worse, the site was riddled with viruses creating havoc with all users as they downloaded hundreds of millions of songs.

Eventually Napster was closed by the government for widespread copyright infreingement. Sony, et.al., felt the threat of low-priced MP3 music was gone, as people would keep buying $20 CDs. But Apple’s new iPod provided mobility in a way that was previously unattainable. Combined with legal downloads, including the emerging Apple Store, meant people could buy music at lower prices, buy only what they wanted and literally listen to it anywhere, remarkably conveniently.

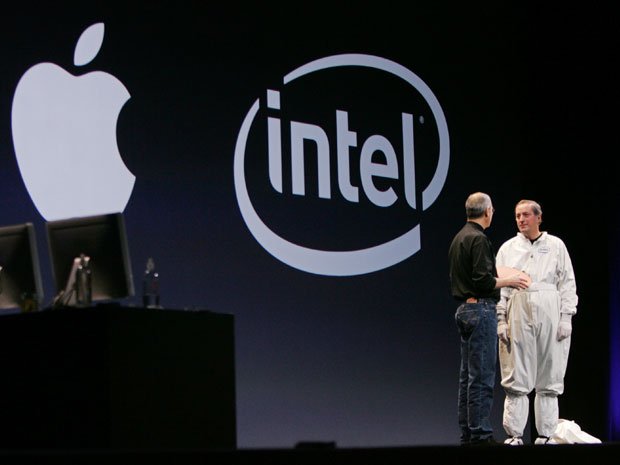

The forecasted “numbers” did not predict Apple’s iPod success. If anything, good analysis led experts to expect the iPod to be a limited success, or possibly failure. (Interestingly, all predictions by experts such as IDC and Gartner for iPhone and iPad sales dramatically underestimated their success, as well – more later.) It was leadership at Apple (led by the returned Steve Jobs) that recognized the trend toward mobility was more important than historical sales analysis, and the new product would not only sell well but change the game on historical leaders.

Which takes us to the mistake Intel made by focusing on “the numbers” when given the opportunity to build chips for the iPhone. Intel was a very successful company, making key components for all Microsoft PCs (the famous WinTel [for Windows+Intel] platform) as well as the Macintosh. So when Apple asked Intel to make new processors for its mobile iPhone, Intel’s leaders looked at the history of what it cost to make chips, and the most likely future volumes. When told Apple’s price target, Intel’s leaders decided they would pass. “The numbers” said it didn’t make sense.

Uh oh. The cost and volume estimates were wrong. Intel made its assessments expecting PCs to remain strong indefinitely, and its costs and prices to remain consistent based on historical trends. Intel used hard, engineering and MBA-style analysis to build forecasts based on models of the past. Intel’s leaders did not anticipate that the new mobile trend, which had decimated Sony’s profits in music as the iPod took off, would have the same impact on future sales of new phones (and eventually tablets) running very thin apps.

Harvard innovation guru Clayton Christensen tells audiences that we have complete knowledge about the past. And absolutely no knowledge about the future. Those who love numbers and analysis can wallow in reams and reams of historical information. Today we love the “Big Data” movement which uses the world’s most powerful computers to rip through unbelievable quantities of historical data to look for links in an effort to more accurately predict the future. We take comfort in thinking the future will look like the past, and if we just study the past hard enough we can have a very predictible future.

But that isn’t the way the business world works. Business markets are incredibly dynamic, subject to multiple variables all changing simultaneously. Chaos Theory lecturers love telling us how a butterfly flapping its wings in China can cause severe thunderstorms in America’s midwest. In business, small trends can suddenly blossom, becoming major trends; trends which are easily missed, or overlooked, possibly as “rounding errors” by planners fixated on past markets and historical trends.

Markets shift – and do so much, much faster than we anticipate. Old winners can drop remarkably fast, while new competitors that adopt the trends become “game changers” that capture the market growth.

In 2000 Apple was the “Mac” company. Pretty much a one-product company in a niche market. And Apple could easily have kept trying to defend & extend that niche, with ever more problems as Wintel products improved.

But by understanding the emerging mobility trend leadership changed Apple’s investment portfolio to capture the new trend. First was the iPod, a product wholly outside the “core strengths” of Apple and requiring new engineering, new distribution and new branding. And a product few people wanted, and industry leaders rejected.

Then Apple’s leaders showed this talent again, by launching the iPhone in a market where it had no history, and was dominated by Motorola and RIMM/BlackBerry. Where, again, analysts and industry leaders felt the product was unlikely to succeed because it lacked a keyboard interface, was priced too high and had no “enterprise” resources. The incumbents focused on their past success to predict the future, rather than understanding trends and how they can change a market.

Too bad for Intel. And Blackberry, which this week failed in its effort to sell itself, and once again changed CEOs as the stock hit new lows.

Then Apple did it again. Years after Microsoft attempted to launch a tablet, and gave up, Apple built on the mobility trend to launch the iPad. Analysts again said the product would have limited acceptance. Looking at history, market leaders claimed the iPad was a product lacking usability due to insufficient office productivity software and enterprise integration. The numbers just did not support the notion of investing in a tablet.

Anyone can analyze numbers. And today, we have more numbers than ever. But, numbers analysis without insight can be devastating. Understanding the past, in grave detail, and with insight as to what used to work, can lead to incredibly bad decisions. Because what really matters is vision. Vision to understand how trends – even small trends – can make an enormous difference leading to major market shifts — often before there is much, if any, data.

by Adam Hartung | Oct 23, 2013 | Current Affairs, Defend & Extend, Food and Drink, Leadership, Lifecycle

On 11 October Safeway announced it was going to either sell or close its 79 Dominick's brand grocery stores in Chicago. After 80 years in Chicago, San Francisco based Safeway leadership felt it was simply time for Dominick's to call it quits.

The grocery industry is truly global, because everyone eats and almost nobody grows their own food. It moves like a giant crude oil carrier, much slower than technology, so identifying trends takes more patience than, say, monitoring annual smartphone cycles. Yet, there are clearly pronounced trends which make a huge difference in performance.

Good for those who recognize them. Bad for those who don't.

Safeway, like a lot of the dominant grocers from the 1970s-1990s, clearly missed the trends.

Coming out of WWII large grocers replaced independent neighborhood corner grocers by partnering with emerging consumer goods giants (Kraft, P&G, Coke, etc.) to bring customers an enormous range of products very efficiently. They offered a larger selection at lower prices. Even though margins were under 10% (think 2% often) volume helped these new grocery chains make good returns on their assets. Dillon's (originally of Hutchinson, Kansas and later purchased by Kroger) became a 1970s textbook, case study model of effective financial management for superior returns by Harvard Business School guru William Fruhan.

But times changed.

Looking at the trend toward low prices, Aldi from Germany came to the U.S. market with a strategy that defines the ultimate in low cost. Often there is only one brand of any product in the store, and that is likely to be the chain's private label. And often it is only available in one size. And customers must be ready to use a quarter to borrow the shopping cart (returned if you replace the cart.) And customers pay for their sacks. Stores are remarkably small and efficient, frequently with only 2 or 3 employees. And with execution so well done that the Aldi brand became #1 in "simple brands" according to a study by brand consultancy Seigal+Gale.

Of course, we also know that big discount chains like WalMart and Target started cherry picking the traditional grocer's enormous SKU (stock keeping units) list, limiting selection but offering lower prices due to lower cost.

Looking at the quality trend, Whole Foods and its brethren demonstrated that people would pay more for better perceived quality. Even though filling the aisles with organic

products and the ultimate in freshness led to higher prices, and someone nicknaming the chain

"whole paycheck," customers payed up to shop there, leading to superior

returns.

Connected to quality has been the trend, which began 30 years ago, to "artisanal" products. Shoppers pay more to buy what are considered limited edition products that are perceived as superior due to a range of "artisanal quality" features; from ingredients used to age of product (or "freshness,") location of manufacture ("local,") extent to which it is considered "organic," quantity of added ingredients for preservation or vitamin enhancement ("less is more,") ecological friendliness of packaging and even producer policies regarding corporate social and ecological responsibility.

But after decades of partnership, traditional grocers today remain dependant on large consumer goods companies to survive. Large CPGs supply a massive number of SKUs in a limited number of contracts, making life easy for grocery store buyers. Big CPGs pay grocers for shelf space, coupons to promote customer purchases, rebates, ads in local store circulars, discounts for local market promotions, sales volumes exceeding commitments and even planograms which instruct employees how to place products on shelves — all saving money for the traditional grocer. In some cases payments and rebates equalling more than total grocer profits.

Additionally, in some cases big CPG firms even deliver their products into the store and stock shelves at no charge to the grocer (called store-door-delivery as a substitute for grocer warehouse and distribution.) And the big CPG firms spend billions of dollars on product advertising to seemingly assure sales for the traditional grocer.

These practices emerged to support the bi-directionally beneficial historically which tied the traditional grocer to the large CPG companies. For decades they made money for both the CPG suppliers and their distributors. Customers were happy.

But the market shifted, and Safeway (including its employees, customers, suppliers and investors) is the loser.

The old retail adage "location, location, location" is no longer enough in grocery. Traditional grocery stores can be located next to good neighborhoods, and execute that old business model really well, and, unfortunately, not make any money. New trends gutted the old Safeway/Dominick's business model (and most of the other traditional grocers) even though that model was based on decades of successful history.

The trend to low price for customers with the least funds led them to shop at the new low-price leaders. And companies that followed this trend, like Aldi, WalMart and Target are the winners.

The trend to higher perceived quality and artisanal products led other customers to retailers offering a different range of products. In Chicago the winners include fast growing Whole Foods, but additionally the highly successful Marianno's division of Roundy's (out of Milwaukee.) And even some independents have become astutely profitable competitors. Such as Joe Caputo & Sons, with only 3 stores in suburban Chicago, which packs its parking lots daily by offering products appealing to these trendy shoppers.

And then there's the Trader Joe's brand. Instead of being all things to all people, Aldi created a new store chain designed to appeal to customers desiring upscale products, and named it Trader Joe's. It bares scance resemblance to an Aldi store. Because it is focused on the other trend toward artisinal and quality. And it too brings in more customers, at higher margin, than Dominick's.

When you miss a trend, it is very, very painful. Even if your model worked for 75 years, and is tightly linked to other giant corporations, new trends lead to market shifts making your old success formula obsolete.

Simultaneously, new trends create opportunities. Even in enormous industries with historically razor-thin margins – or even losses. Building on trends allows even small start-up companies to compete, and make good profits, in cutthroat industries – like groceries.

Trends really matter. Leaders who ignore the trends will have companies that suffer. Meanwhile, leaders who identify and build on trends become the new winners.

by Adam Hartung | Oct 9, 2013 | Current Affairs, In the Rapids, Innovation, Lifecycle

In 1985 there was universal agreement that investors should

be heavily in pharmaceuticals.

Companies like Merck, Eli Lilly, Pfizer, Sanofi, Roche, Glaxo and Abbott

were touted as the surest route to high portfolio returns.

Today, not so much.

Merck, once a leader in antibiotics, is laying off 20% of

its staff. Half in R&D; the

lifeblood of future products and profits.

Lilly is undertaking

another round of 2013 cost cuts. Over

the last year about 100,000 jobs have been eliminated in big pharma companies,

which have implemented spin-outs and split-ups as well as RIFs.

What happened? In the old days pharma companies had to demonstrate

their drug worked; called product efficacy. It did not have to be better than existing drugs. If the drug worked, without big safety

issues, the company could launch it.

Then the business folks took over with ads, distribution,

salespeople and convention booths, convincing doctors to prescribe and us to

buy.

Big pharma companies grew into large, masterful consumer

products companies. Leadership’s view of the market changed, as it was

perceived safer to invest in Pepsi vs. Coke marketing tactics and sales warfare

to dominate a blockbuster category than product development. Think of the marketing cost in the

Celebrex vs. Vioxx war. Or Viagra

vs. Cialis.

But the market shifted when the FDA decided new drugs had to

be not only efficacious, they had to enhance the standard of care. New drugs actually had to prove better in clinical trials than existing

drugs. And often safer, too.

Hurrumph. Big pharma’s enormous scale advantages in

marketing and communication weren’t enough to assure new product success. It actually took new products. But that meant bigger R&D investments,

perceived as more risky, than the new consumer-oriented pharma companies could

tolerate. Shortly pipelines

thinned, generics emerged and much lower margins ensued.

In some disease areas, this evolution was disastrous for

patients. In antibiotics,

development of new drugs had halted.

Doctors repeatedly prescribed (some say overprescribed) the same antibiotics. As the bacteria evolved, infections

became more difficult to treat.

With no new antibiotics on the market the risk of death from

bacterial infections grew, leading to a national public health crisis. According to the Centers for Disease

Control (CDC) there are over 2 million cases of antibiotic resistant infections

annually. Today just one type of

resistant “staph infection,” known as MRSA, kills more people in the USA than

HIV/AIDs – killing more people every year than polio did at its peak. The most

difficult to treat pathogens (called ESKAPE) are the cause of 66% of hospital

infections.

And that led to an important market shift – via regulation

(Congress?!?!)

With help from the CDC and NIH, the Infectious Diseases

Society of America pushed through the GAIN (Generating Antibiotic Incentives

Now) Act (H.R. 2182.) This gave

creators of new antibiotics the opportunity for new, faster pathways through

clinical trials and review in order to expedite approvals and market launch.

Additionally new product market exclusivity was lengthened an additional 5

years (beyond the normal 5 years) to enhance investor returns.

Which allowed new game changers like Melinta Therapeutics

into the game.

Melinta (formerly Rib-X) was once considered a “biopharma science

company” with Nobel Prize-winning technology, but little hope of commercial

product launch. But now the large

unmet need is far clearer, the playing field has few to no large company

competitors, the commercialization process has been shortened and cheapened,

and the opportunity for extended returns is greater!

Venture firm Vatera Healthcare Partners, with a history of investing in game changers (especially transformational technology,) entered the picture as lead investor. Vatera's founder Michael Jaharis quickly hired Mary Szela, the former head of U.S.

Pharmaceuticals for Abbott (now Abbvie) as CEO. Her resume includes leading the growth of Humira, one of

the world’s largest pharma brands with multi-billion dollar annual sales.

Under her guidance Melinta has taken fast action to work

with the FDA on a much quicker clinical trials pathway of under 18 months for

commercializing delafloxacin. In layman’s

language, early trials of delafloxacin appeared to provide better performance

for a broad spectrum of resistant bacteria in skin infections. And as a one-dose oral (or IV)

application it could be a simpler, high quality solution for gonorrhea.

Melinta continues adding key management resources as it

seeks “breakthrough product” designation under GAIN from the FDA for its RX-04

product. RX-04 is an entirely

different scientific approach to infectious disease control, based on that previously

mentioned proprietary, Nobel-winning ribosome science. It’s a potential product category

game changer that could open the door for a pipeline of follow-on products.

Melinta is using GAIN to do something big pharma, with its

shrinking R&D and commercial staff, is unable to accomplish. Melinta is helping

redefine the rules for approving antibiotics, in order to push through new,

life-saving products.

The best news is that this game change is great for investors.

Those companies who understand the

trend (in this case, the urgent need for new antibiotics) and how the market

has shifted (GAIN,) are putting in place teams to leverage newly invented drugs

working with the FDA. Investment timelines and dollars are looking

far more manageable – and less risky.

Twenty-five years ago pharma looked like a big-company-only

market with little competition and huge returns for a handful of companies. But things changed. Now companies (like Melinta) with new

solutions have the opportunity to move much faster to prove efficacy and safety

– and save lives. They are the

game changers, and the ones more likely to provide not only solutions to the

market but high investor returns.

by Adam Hartung | Sep 30, 2013 | Current Affairs, Defend & Extend, Leadership, Lock-in

Last week we learned that there is no doubt, the world is warming. A U.N. report affirmed by some 1,000 scientists asserted 95% confidence as to the likely outcomes, as well as the cause. We must expect more volatility in weather, and that the oceans will continue rising.

Yet, most people really could have cared less. And a vocal minority still clings to the notion that because the prior decade saw a slower heating, perhaps this will all just go away.

Incredibly, for those of us who don't live and work in Florida, there was CNN news footage of daily flooding in Miami's streets due to current sea levels which have risen over last 50 years. Given that we can now predict the oceans will rise between 1 and 6 feet in the next 50 years, it is possible to map the large areas of Miami streets which are certain to be flooded.

There is just no escaping the fact that the long-term trend of global warming will have a remarkable impact on everyone. It will affect transportation, living locations, working locations, electricity generation and distribution, agriculture production, textile production – everything will be affected. And because it is happening so slowly, we actually can do lots of modeling about what will happen.

Yet, I never hear any business leaders talk about how they are planning for global warning. No comments about how they are making changes to keep their business successful. Nor comments about the new opportunities this will create. Even though the long-term impacts will be substantial, the weather and how it affects us is treated like the status quo.

What does this have in common with the government shutdown?

America has known for decades that its healthcare system was dysfunctional; to be polite. It was incredibly expensive (by all standards) and yet had no better outcomes for citizens than other modern countries. For over 20 years efforts were attempted to restructure health care. Yet as the morass of regulations ballooned, there was no effective overhaul that addressed basic problems built into the system. Costs continued to soar, and more people joined the ranks of those without health care, while other families were bankrupted by illness.

Finally, amidst enormous debate, the Affordable Care Act was passed. Despite wide ranging opinions from medical doctors, nurses, hospital and clinic administrators, patient advocacy groups, pharmaceutical companies, medical device companies and insurance companies (to name just some of those with a vested interest and loud, competing, viewpoints) Congress passed the Affordable Care Act which the President signed.

Like most such things in America, almost nobody was happy. No one got what they wanted. It was one of those enormous, uniquely American, compromises. So, like unhappy people do in America, we sued! And it took a few years before finally the Supreme Court ruled that the legislation was constitutional. The Affordable Care Act would be law.

But, people remain who simply do not want to accept the need for health care change. So, in a last ditch effort to preserve the status quo, they are basically trying to kidnap the government budget process and hold it hostage until they get their way. They have no alternative plan to replace the Affordable Care Act. They simply want to stop it from moving forward.

What global warming and the government shut down have in common are:

- Very long-term problems

- No quick solution for the problem

- No easy solution for the problem

- If you do nothing about the problem today, you have no immediate calamity

- Doing anything about the problem affects almost everyone

- Doing anything causes serious change

So, in both cases, people have emerged as the Status Quo Police. They take on the role of stopping change. They will do pretty much anything to defend & extend the status quo:

- Ignore data that is contradictory to the best analytical views

- Claim that small probability outcomes (that change may not be necessary) justifies doing nothing

- Delay, delay, delay taking any action until a disaster requires action

- Constantly claim that the cost of change is not justified

- Claim that the short-term impact of change is more deleterious than the long-term benefits

- Assume that the status quo will somehow resolve itself favorably – with no supporting evidence or analysis

- Undertake any action that preserves the status quo

- Threaten a "scorched earth policy" (that they will create big, immediate problems if forced to change the status quo)

The earth is going to become warmer. The oceans will rise, and other changes will happen. If you don't incorporate this in your plans, and take action, you can expect this trend will harm you.

U.S. health care is going to be reformed. How it will happen is just starting. How it will evolve is still unclear. Those who create various scenarios in their plans to prepare for this change will benefit. Those who do nothing, hoping it goes away, will find themselves struggling.

The Status Quo Police, trying their best to encourage people to ignore the need for change – the major, important trends – are helping nobody. By trying to preserve the status quo they inhibit effective planning, and action, to prepare for a different (better) future.

Does your organization have Status Quo Police? Are their functions, groups or individuals who are driven to defend and extend the status quo – even in the face of trends that demonstrate change is necessary? Can they stop conversations around substantial change? Are they allowed to stop future planning for scenarios that are very different from the past? Can they enforce cultural norms that stop considering new alternatives? Can they control resources resulting in less innovation and change?

Let's learn from these 2 big issues. Change is inevitable. It is even necessary. Trying to preserve the status quo is costly, and inhibits taking long-term effective action. Status Quo Police are obstructionists who keep us from facing, and solving, difficult problems. They don't help our organizations create a new, more successful future. Only by overcoming them can we reach our full potential, and create opportunities out of change.

by Adam Hartung | Sep 19, 2013 | Current Affairs, In the Swamp, Innovation, Leadership, Television, Web/Tech

Apple announced the new iPhones recently. And mostly, nobody cared.

Remember when users waited anxiously for new products from Apple? Even the media became addicted to a new round of Apple products every few months. Apple announcements seemed a sure-fire way to excite folks with new possibilities for getting things done in a fast changing world.

But the new iPhones, and the underlying new iPhone software called iOS7, has almost nobody excited.

Instead of the product launches speaking for themselves, the CEO (Tim Cook) and his top product development lieutenants (Jony Ive and Craig Federighi) have been making the media rounds at BloombergBusinessWeek and USAToday telling us that Apple is still a really innovative place. Unfortunately, their words aren't that convincing. Not nearly as convincing as former product launches.

CEO Cook is trying to convince us that Apple's big loss of market share should not be troubling. iPhone owners still use their smartphones more than Android owners, and that's all we should care about. Unfortunately, Apple profits come from unit sales (and app sales) rather than minutes used. So the chronic share loss is quite concerning.

Especially since unit sales are now growing barely in single digits, and revenue growth quarter-over-quarter, which sailed through 2012 in the 50-75% range, have suddenly gone completely flat (less than 1% last quarter.) And margins have plunged from nearly 50% to about 35% – more like 2009 (and briefly in 2010) than what investors had grown accustomed to during Apple's great value rise. The numbers do not align with executive optimism.

For industry aficianados iOS7 is a big deal. Forbes Haydn Shaughnessy does a great job of laying out why Apple will benefit from giving its ecosystem of suppliers a new operating system on which to build enhanced features and functionality. Such product updates will keep many developers writing for the iOS devices, and keep the battle tight with Samsung and others using Google's Android OS while making it ever more difficult for Microsoft to gain Windows8 traction in mobile.

And that is good for Apple. It insures ongoing sales, and ongoing profits. In the slog-through-the-tech-trench-warfare Apple is continuing to bring new guns to the battle, making sure it doesn't get blown up.

But that isn't why Apple became the most valuable publicly traded company in America.

We became addicted to a company that brought us things which were great, even when we didn't know we wanted them – much less think we needed them. We were happy with CDs and Walkmen until we discovered much smaller, lighter iPods and 99cent iTunes. We were happy with our Blackberries until we learned the great benefits of apps, and all the things we could do with a simple smartphone. We were happy working on laptops until we discovered smaller, lighter tablets could accomplish almost everything we couldn't do on our iPhone, while keeping us 24×7 connected to the cloud (that we didn't even know or care about before,) allowing us to leave the laptop at the office.

Now we hear about upgrades. A better operating system (sort of sounds like Microsoft talking, to be honest.) Great for hard core techies, but what do users care? A better Siri; which we aren't yet sure we really like, or trust. A new fingerprint reader which may be better security, but leaves us wondering if it will have Siri-like problems actually working. New cheaper color cases – which don't matter at all unless you are trying to downgrade your product (sounds sort of like P&G trying to convince us that cheaper, less good "Basic" Bounty was an innovation.)

More (upgrades) Better (voice interface, camera capability, security) and Cheaper (plastic cases) is not innovation. It is defending and extending your past success. There's nothing wrong with that, but it doesn't excite us. And it doesn't make your brand something people can't live without. And, while it keeps the battle for sales going, it doesn't grow your margin, or dramatically grow your sales (it has declining marginal returns, in fact.)

And it won't get your stock price from $450-$475/share back to $700.

We all know what we want from Apple. We long for the days when the old CEO would have said "You like Google Glass? Look at this……. This will change the way you work forever!!"

We've been waiting for an Apple TV that let's us bypass clunky remote controls, rapidly find favorite shows and helps us avoid unwanted ads and clutter. But we've been getting a tease of Dick Tracy-esque smart watches.

From the world's #1 tech brand (in market cap – and probably user opinion) we want something disruptive! Something that changes the game on old companies we less than love like Comcast and DirecTV. Something that helps us get rid of annoying problems like expensive and bad electric service, or routers in our basements and bedrooms, or navigation devices in our cars, or thumb drives hooked up to our flat screen TVs —- or doctor visits. We want something Game Changing!

Apple's new CEO seems to be great at the Sustaining Innovation game. And that pretty much assures Apple of at least a few more years of nicely profitable sales. But it won't keep Apple on top of the tech, or market cap, heap. For that Apple needs to bring the market something big. We've waited 2 years, which is an eternity in tech and financial markets. If something doesn't happen soon, Apple investors deserve to be worried, and wary.