by Adam Hartung | May 16, 2011 | Defend & Extend, In the Swamp, Leadership, Lifecycle, Lock-in, Web/Tech

In “Screening Large Cap Value Stocks” 24x7WallSt.com tries making the investment case for Dell. And backhandedly, for Hewlett Packard. The argument is as simple as both companies were once growing, but growth slowed and now they are more mature companies migrating from products into services. They have mounds of cash, and will soon start paying a big, fat dividend. So investors can rest comfortably that these big companies are a good value, sitting on big businesses, and less risky than growth stocks.

Nice story. Makes for good myth. Reality is that these companies are a lousy value, and very risky.

Dell grew remarkably fast during the PC growth heyday. Dell innovated computer sales, eschewing expensive distribution for direct-to-customer marketing and order-taking. Dell could sell individuals, or corporations, computers off-the-shelf or custom designed machines in minutes, delivered in days. Further, Dell eschewed the costly product development of competitors like Compaq in favor of using a limited number of component suppliers (Microsoft, Intel, etc.) and focusing on assembly. With Wal-Mart style supply chain execution Dell could deliver a custom order and be paid before the bill was due for parts. Quickly Dell was a money-making, high growth machine as it rode the growth of PC sales expansion.

But competitors learned to match Dell’s supply chain cost-cutting capabilities. Manufacturers teamed with retailers like Best Buy to lower distribution cost. As competition copied the use of common components product differences disappeared and prices dropped every month. Dell’s advantages started disappearing, and as they continued to follow the historical cost-cutting success formula with more outsourcing, problems developed across customer services. Competitors wreaked havoc on Dell’s success formula, hurting revenue growth and margins.

HP followed a similar path, chasing Dell down the cost curve and expanding distribution. To gain volume, in hopes that it would create “scale advantages,” HP acquired Compaq. But the longer HP poured printer profits into PCs, the more it fed the price war between the two big companies.

Worst for both, the market started shifting. People bought fewer PCs. Saturation developed, and reasons to buy new ones were few. Users began buying more smartphones, and later tablets. And neither Dell nor HP had any products in development where the market was headed, nor did their “core” suppliers – Microsoft or Intel.

That’s when management started focusing on how to defend and extend the historical business, rather than enter growth markets. Rather than moving rapidly to push suppliers into new products the market wanted, both extended by acquiring large consulting businesses (Dell famously bought Perot Systems and HP bought EDS) in the hopes they could defend their PC installed base and create future sales. Both wanted to do more of what they had always done, rather than shift with emerging market needs.

But not only product sales were stagnating. Services were becoming more intensely competitive – from domestic and offshore services providers – hampering sales growth while driving down margins. Hopes of regaining growth in the “core” business – especially in the “core” enterprise markets – were proving illusory. Buyers didn’t want more PCs, or more PC services. They wanted (and now want) new solutions, and neither Dell nor HP is offering them.

So the big “cash hoard” that 24×7 would like investors to think will become dividends is frittered away by company leadership – spent on acquisitions, or “special projects,” intended to save the “core” business. When allocating resources, forecasts are manipulated to make defensive investments look better than realistic. Then the “business necessity” argument is trotted out to explain why acquisitions, or price reductions, are necessary to remain viable, against competitors, even when “the numbers” are hard to justify – or don’t even add up to investor gains. Instead of investing in growth, money is spent trying to delay the market shift.

Take for example Microsoft’s recent acquisition of Skype for $8.5B. As Arstechnia.com headlined “Why Skype?” This acquisition is another really expensive effort by Microsoft to try keeping people using PCs. Even though Microsoft Live has been in the market for years, Microsoft keeps trying to find ways to invest in what it knows – PCs – rather than invest in solutions where the market is shifting. New smartphone/tablet products come with video capability, and are already hooked into networks. Skype is the old generation technology, now purchased for an enormous sum in an effort to defend and extend the historical base.

There is no doubt people are quickly shifting toward smartphones and tablets rather than PCs. This is an irreversable trend:  Chart source BusinessInsider.com

Chart source BusinessInsider.com

Executive teams locked-in to defending their past spend resources over-investing in the old market, hoping they can somehow keep people from shifting. Meanwhile competitors keep bringing out new solutions that make the old obsolete. While Microsoft was betting big on Skype last week Mediapost.com headlined “Google Pushes Chromebook Notebooks.” In a direct attack on the “core” customers of Dell and HP (and Microsoft) Google is offering a product to replace the PC that is far cheaper, easier to use, has fewer breakdowns and higher user satisfaction.

Chromebooks don’t have to replace all PCs, or even a majority, to be horrific for Dell and HP. They just have to keep sucking off all the growth. Even a few percentage points in the market throws the historical competitors into further price warring trying to maintain PC revenues – thus further depleting that cash hoard. While the old gladiators stand in the colliseum, swinging axes at each other becoming increasingly bloody waiting for one to die, the emerging competitors avoid the bloodbath by bringing out new products creating incremental growth.

People love to believe in “value stocks.” It sounds so appealing. They will roll along, making money, paying dividends. But there really is no such thing. New competitors pressure sales, and beat down margins. Markets shift wtih new solutions, leaving fewer customers buying what all the old competitors are selling, further driving down margins. And internal decision mechanisms keep leadership spending money trying to defend old customers, defend old solutions, by making investments and acquisitions into defensive products extending the business but that really have no growth, creating declining margins and simply sucking away all that cash. Long before investors have a chance to get those dreamed-of dividends.

This isn’t just a high-tech story. GM dominated autos, but frittered away its cash for 30 years before going bankrupt. Sears once dominated retailing, now its an irrelevent player using its cash to preserve declining revenues (did you know Woolworth’s was a Dow Jones company until 1997?). AIG kept writing riskier insurance to maintain its position, until it would have failed if not for a buyout. Kodak never quit investing in film (remember 110 cameras? Ektachrome) until competitors made film obsolete. Xerox was the “copier company” long after users switched to desktop publishing and now paperless offices.

All of these were once called “value investments.” However, all were really traps. Although Dell’s stock has gyrated wildly for the last decade, investors have lost money as the stock has gone from $25 to $15. HP investors have fared a bit better, but the long-term trending has only had the company move from about $40 to $45. Dell and HP keep investing cash in trying to find past glory in old markets, but customers shift to the new market and money is wasted.

When companies stop growing, it’s because markets shift. After markets shift, there isn’t any value left. And management efforts to defend the old success formula with investments in extensions simply fritter away investor money. That’s why they are really value traps. They are actually risky investments, because without growth there is little likelihood investors will ever see a higher stock price, and eventually they always collapse – it’s just a matter of when. Meanwhile, riding the swings up and down is best left for day traders – and you sure don’t want to be long the stock when the final downturn hits.

by Adam Hartung | May 3, 2011 | Current Affairs, Defend & Extend, In the Swamp, Leadership, Lock-in, Web/Tech

For the first time in 20 years, Apple’s quarterly profit exceeded Microsoft’s (see BusinessWeek.com “Microsoft’s Net Falls Below Apple As iPad Eats Into Sales.) Thus, on the face of things, the companies should be roughly equally valued. But they aren’t. This week Microsoft’s market capitalization is about $215B, while Apple’s is about $365B – about 70% higher. The difference is, of course, growth – and how a lack of it changes management!

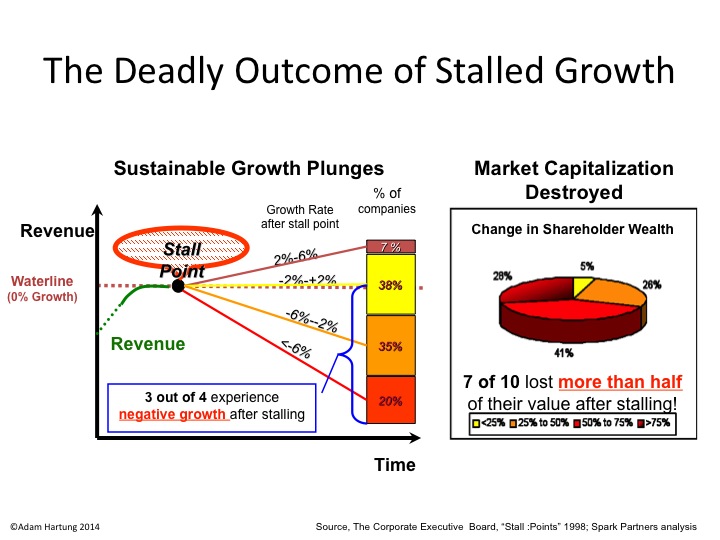

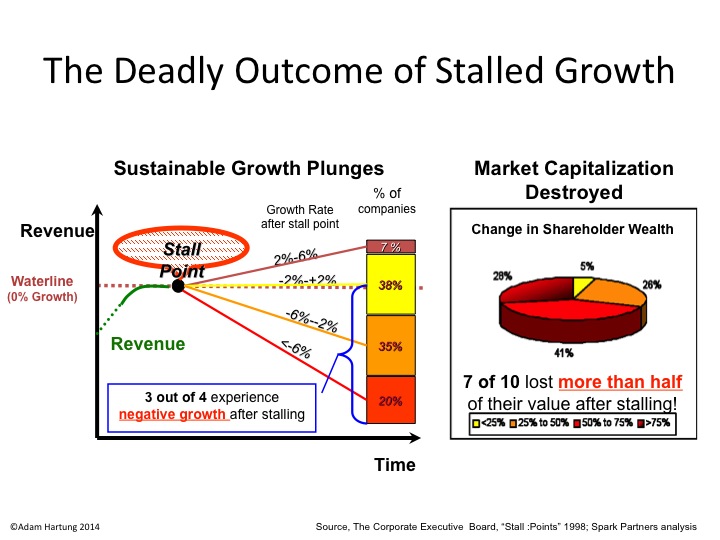

According to the Conference Board, growth stalls are deadly.

When companies hit a growth stall, 93% of the time they are unable to maintain even a 2% growth rate. 75% fall into a no growth, or declining revenue environment, and 70% of them will lose at least half their market capitalization. That’s because the market has shifted, and the business is no longer selling what customers really want.

At Microsoft, we see a company that has been completely unable to deal with the market shift toward smartphones and tablets:

- Consumer PC shipments dropped 8% last quarter

- Netbook sales plunged 40%

Quite simply, when revenues stall earnings become meaningless. Even though Microsoft earnings were up, it wasn’t because they are selling what customers really want to buy. In stalled companies, executives cut costs in sales, marketing, new product development and outsource like crazy in order to prop up earnings. They can outsource many functions. And they go to the reservoir of accounting rules to restate depreciation and expenses, delaying expenses while working to accelerate revenue recognition.

Stalled company management will tout earnings growth, even though revenues are flat or declining. But smart investors know this effort to “manufacture earnings” does not create long-term value. They want “real” earnings created by selling products customers desire; that create incremental, new demand. Success doesn’t come from wringing a few coins out of a declining market – but rather from being in markets where people prefer the new solutions.

Mobile phone sales increased 20% (according to IDC), and Apple achieved 14% market share – #3 – in USA (according to MediaPost.com) last quarter. And in this business, Apple is taking the lion’s share of the profits:

Image provided by BusinessInsider.com

When companies are growing, investors like that they pump earnings (and cash) back into growth opportunities. Investors benefit because their value compounds. In a stalled company investors would be better off if the company paid out all their earnings in dividends – so investors could invest in the growth markets.

But, of course, stalled companies like Microsoft and Research in Motion, don’t do that. Because they spend their cash trying to defend the old business. Trying to fight off the market shift. At Microsoft, money is poured into trying to protect the PC business, even as the trend to new solutions is obvious. Microsoft spent 8 times as much on R&D in 2009 as Apple – and all investors received was updates to the old operating system and office automation products. That generated almost no incremental demand. While revenue is stalling, costs are rising.

At Gurufocus.com the argument is made “Microsoft Q3 2011: Priced for Failure“. Author Alex Morris contends that because Microsoft is unlikely to fail this year, it is underpriced. Actually, all we need to know is that Microsoft is unlikely to grow. Its cost to defend the old business is too high in the face of market shifts, and the money being spent to defend Microsoft will not go to investors – will not yield a positive rate of return – so investors are smart to get out now!

Additionally, Microsoft’s cost to extend its business into other markets where it enters far too late is wildly unprofitable. Take for example search and other on-line products:

Chart source BusinessInsider.com

While much has been made of the ballyhooed relationship between Nokia and Microsoft to help the latter enter the smartphone and tablet businesses, it is really far too late. Customer solutions are now in the market, and the early leaders – Apple and Google Android – are far, far in front. The costs to “catch up” – like in on-line – are impossibly huge. Especially since both Apple and Google are going to keep advancing their solutions and raising the competitive challenge. What we’ll see are more huge losses, bleeding out the remaining cash from Microsoft as its “core” PC business continues declining.

Many analysts will examine a company’s earnings and make the case for a “value play” after growth slows. Only, that’s a mythical bet. When a leader misses a market shift, by investing too long trying to defend its historical business, the late-stage earnings often contain a goodly measure of “adjustments” and other machinations. To the extent earnings do exist, they are wasted away in defensive efforts to pretend the market shift will not make the company obsolete. Late investments to catch the market shift cost far too much, and are impossibly late to catch the leading new market players. The company is well on its way to failure, even if on the surface it looks reasonably healthy. It’s a sucker’s bet to buy these stocks.

Rarely do we see such a stark example as the shift Apple has created, and the defend & extend management that has completely obsessed Microsoft. But it has happened several times. Small printing press manufacturers went bankrupt as customers shifted to xerography, and Xerox waned as customers shifted on to desktop publishing. Kodak declined as customers moved on to film-less digital photography. CALMA and DEC disappeared as CAD/CAM customers shifted to PC-based Autocad. Woolworths was crushed by discount retailers like KMart and WalMart. B.Dalton and other booksellers disappeared in the market shift to Amazon.com. And even mighty GM faltered and went bankrupt after decades of defend behavior, as customers shifted to different products from new competitors.

Not all earnings are equal. A dollar of earnings in a growth company is worth a multiple. Earnings in a declining company are, well, often worthless. Those who see this early get out while they can – before the company collapses.

Update 5/10/11 – Regarding announced Skype acquisition by Microsoft

That Microsoft has apparently agreed to buy Skype does not change the above article. It just proves Microsoft has a lot of cash, and can find places to spend it. It doesn’t mean Microsoft is changing its business approach.

Skype provides PC-to-PC video conferencing. In other words, a product that defends and extends the PC product. Exactly what I predicted Microsoft would do. Spend money on outdated products and efforts to (hopefully) keep people buying PCs.

But smartphones and tablets will soon support video chat from the device; built in. And these devices are already connected to networks – telecom and wifi – when sold. The future for Skype does not look rosy. To the contrary, we can expect Skype to become one of those features we recall, but don’t need, in about 24 to 36 months. Why boot up a PC to do a video chat you can do right from your hand-held, always-on, device?

The Skype acquisition is a predictable Defend & Extend management move. It gives the illusion of excitement and growth, when it’s really “so much ado about nothing.” And now there are $8.5B fewer dollars to pay investors to invest in REAL growth opportunities in growth markets. The ongoing wasting of cash resources in an effort to defend & extend, when the market trends are in another direction.

by Adam Hartung | Oct 27, 2010 | Current Affairs, Defend & Extend, In the Swamp, Leadership, Web/Tech

Summary:

- We like to think of "mature" businesses as good

- AT&T was a "mature" business, yet it failed

- "Maturity" leads to inward focus, and an unwillingness to adjust to market shifts

- Microsoft is trying to reposition itself as a "mature" company

- Despite its historical strengths, Microsoft has astonishing parallels to AT&T

- Growth is less risky than "maturity" for investors, employees and customers

Why doesn't your business grow like Apple or Google? Is it because you think of your business, or the marketplace you serve, as "mature?" Quite a euphanism, maturity. It sounds so good. How could being "mature" be bad? As children we strive to be "mature." The leader is usually the most "mature" person in the group. Those who like good art have "mature" taste. Surely, we should want to be "mature." And we should want our businesses to reach "maturity" and have "mature" leaders who don't take unnecessary risks. Once "mature" the business should be safe for investors, employees, suppliers and customers.

That was probably what the folks at AT&T thought. When judge Greene broke up AT&T in 1984 the company had a near monopoly on long-distance. AT&T was a "mature" company in a "mature" telephone industry. It appeared as though all AT&T had to do was keep serving its customers, making regular improvements to its offering, to perpetually maintain its revenue, jobs and profitability. A very "mature" company, AT&T's "mature" management knew everything there was to know about long distance – about everything related to communications. And due to its previous ownership of Bell Labs and Western Union, it had deep knowledge about emerging technologies and manufacturing costs allowing AT*T to make "mature" decisions about investing in future markets and products. This "mature" company would be able to pay out dividends forever! It seemed ridiculous to think that AT&T would go anywhere but up!

Unfortunately, things didn't work out so well. The "mature" AT&T saw its market share attacked by upstarts MCI and Sprint. As a few "early adopters" switched services – largely residential and other very small customers – AT&T was unworried. It still had most of the market and fat profits. As these relatively insignificant small users switched, AT&T reinforced its world's largest billing system as an incomparable strength, and reminded everyone that its "enterprise" (corporate) offerings were still #1 (anybody remember AT&T long distance cards issued by your employer for use at pay phones?).

But unfortunately, what looked like an unassailable market position in 1984 was eventually diminished dramatically as not only homeowners but corporations started shifting to new offerings from competitors. New pricing plans, "bundled" products and ease of use encouraged people to try a new provider. And that AT&T had become hard to work with, full of rules and procedures that were impossible for the customer to comprehend, further encouraged people to try an alternative. Customers simply got fed up with rigid service, outdated products and high prices.

Unexpectedly, for AT&T, new markets started to grow much faster and become more profitable than long distance voice. Data services started using a lot more capacity, and even residential customers started wanting to log onto the internet. Even though AT&T had been the leader (and onetime monopolist – did you know broadcast television was distributed over an AT&T network?) with these services, this "mature" company continued to focus on its traditional voice business – and was woefully late to offer commercial or residential customers new products. Not only were dial-up offerings delayed, but higher speed ISDN and DSL services went almost entirely to competitors.

And, much to the chagrin of AT&T leaders, customers started using their mobile phones a lot more. Initially viewed as expensive toys, AT&T did not believe that the infrastructure would be built quickly, nor be robust enough, to support a large base of cellular phone users. Further, AT&T anticipated pricing would keep most people from using these new products. Not to mention the fact that these new phones simply weren't very good – as compared to land-line services according to the metrics used by AT&T. The connection quality was wildly inferior to traditional long distance, and frequently calls were completely dropped! So AT&T was slow to enter this market, half-hearted in its effort, and failed to make any profits.

Along the way a lot of other "non-core" business efforts failed. There was the acquisition of Paradyne, an early leader in modems, that did not evolve with fast changing technology. New products made Paradyne's early products obsolete and the division disappeared. And the acquisition of computer maker NCR failed horribly after AT&T attempted to "improve" management and "synergize" it with the AT&T customer base and offerings.

AT&T had piles and piles of cash from its early monopoly. But most of that money was spent trying to defend the long distance business. That didn't work. Then there was money lost by wheelbarrow loads trying to enter the data and mobile businesses too late, and with little new to offer. And of course the money spent on acquisitions that AT&T really didn't know how to manage was all down the proverbial drain.

Despite its early monopoly, high cash flow, technology understanding, access to almost every customer and piles of cash, AT&T failed. Today the company named AT&T is a renamed original regional Bell operatiing company (RBOC) created in the 1984 break-up — Southwestern Bell. This classically "mature" company, a stock originally considered "safe" for investing in the "widow's and orphan's fund" used up its money and became obsolete. "Mature" was a misnomer used to allow AT&T to hide within itself; to focus on its past, instead of its future. By being satisfied with saying it was "mature" and competing in "mature" markets, AT&T allowed itself to ignore important market shifts. In just 25 years the company that ushered in mass communications, that had an incredibly important history, disappeared.

I was struck today when a Reuters story appeared with the headline "Sleepy in Seattle: Microsoft Learns to Mature." There's that magic word – "mature." While the article lays out concerns with Microsoft, there were still analysts quoted as saying that investors didn't need to worry about Microsoft's future. Investors simply need to change their thinking. Instead of a "growth" company, they should start thinking of Microsoft as a "mature" company. It sounds so reassuring. After all:

- Microsoft has a near monopoly in its historical business

- Microsoft has a huge R&D budget, and is familiar with all the technologies

- Microsoft has piles and piles of cash

- Microsoft has huge margins in its traditional business – in fact profits in operating systems and office automation exceed 100% of the total because it loses billions of dollars in other things like Bing, MSN and its incredibly expensive foray into gaming systems (xBox)

- Markets won't shift any time soon – say to this new "cloud computing" – and Microsoft will surely have products when they are needed if there is a market shift

- While home users may buy these new smartphones, tablets and some Macs, enterprise customers will keep using the technology they've long purchased

- Microsoft is smart to move slowly into new markets, it shouldn't cannibalize its existing business by encouraging customers to change platforms. Going slow and being late is a good thing for profits

- Although Microsoft has been late to smartphones and tablets, with all their money and size surely when they do get to market they will beat these upstarts Apple and Google, et. al.

Sure made me think about AT&T. And the fact that Apple is now worth more than Microsoft. Made me wonder just how comfortable investors should be with a "mature" Microsoft. Made me wonder how much investors, employees and customers should trust a "mature" CEO Ballmer.

Looking at the last 10 years, it seems like there's a lot more risk in "mature" companies than in "growth" ones. We can be almost certain that Apple and Google, which have produced huge returns for investors, will grow for the next 3 years, improving cash flow and profitability just by remaining in existing new markets. But of course both have ample new products pioneering yet more new markets. And companies like NetApp look pretty safe, building a fast-growing base of customers who are already switching to cloud computing – and producing healthy cash flow in the emerging marketplace.

Meanwhile, the track record for "mature" companies would leave something to be desired. One could compare Amazon to Circuit City or Sears. Or just list some names: AT&T, General Motors, Chrysler, Xerox, Kodak, AIG, Citibank, Dell, EDS, Sun Microsystems. Of course each of these is unique, with its own story. Yet….

by Adam Hartung | Apr 15, 2010 | Defend & Extend, In the Swamp, Leadership, Lock-in, Web/Tech

Hi, two readings recently have really surprised me.

Firstly, Dawn Beaupariant from the public relations firm Waggener Edstrom contacted me regarding my Forbes column. I learned this firm is the PR agency for Microsoft. They took exception to my Forbes column ("Microsoft's Dismal Future"). But not because any facts were inaccurate.

Rather, it was their point of view that because OS 7 is now the largest selling OS of all time that demonstrated it was a successful product. Of course, when the television standard was changed in the USA to digital and everyone had to transition set-top boxes those also became big sellers. But it wasn't because everybody wanted the new product. More, it was the impact of a monopolist. We all know Microsoft has had a near monopoly in PC operating systems (even though every year it is losing share to Linux), so the fact that they can force people to use a new one on new machines, or upgrade, is less than an enthusiastic market endorsement of the product. For every "reviewer" who likes OS 7, there are 100 users saying "this gives me bells and whistles I don't need or want, and complicates my life. Can I simply keep my old product, or do my work on my smartphone?"

The Forbes column didn't debate whether Microsoft was likely to remain dominant in PC operating systems – that is a foregone conclusion. The issue is that markets are shifting away from PCs to mobile devices. And Microsoft has lost 2/3 its market share in mobile operating systems. And it is not developing a strong product. If people keep shifting from PCs to Blackberry's, iPhones and Androids – and PC sales start declining – in 10 years Microsoft could dominate PC OS sales (and Office applications) but it may not matter. Too bad the PR firm didn't get that.

Secondly, the PR firm claimed that Microsoft could put forward new products readily, leading to capturing dominant share in new markets. Their one claim that Microsoft had accomplished this was xBox. The PR person conveniently ignored the smartphone market, the Zune-style handheld market, the market for mobile applications (where Apple sold 2billion apps in its first 18 months), the search market (where Microsoft lags Google and would be nowhere without picking up Yahoo!'s declining business) and a host of other markets where Microsoft simply let the horse out of the barn.

To make matters worse, as Microsoft has invested to Defend the PC operating system and office products business, xBox is losing market share (exactly the point I made in the article – using the smartphone example instead)! According to IndustryGamers.com "PS3 'Steadily Increasing' Market Share Across the Globe" (Feb, 2010). Bad pick Dawn!

- The PS3 is dominant in Japan and Korea, and as of June 2008, has begun

to outsell the Xbox 360 in Europe. It is also steadily increasing its

market share in all other regions across the globe, including in the

North American market

- PS3 sales have been surging (44%

over the holidays) and SCEA senior vice president of Marketing and

PlayStation Network, Peter Dille, recently insisted that PS3

will eventually overtake Xbox 360

Most commenters have reflected my viewpoint, saying that they see Microsoft so horribly Locked-in to its old business that it is almost GM-like in its approach to new products and markets. Not a good sign. Those who defend Microsoft simply take the point of view that Microsoft is huge, has high share in PCs, and is very profitable in OS and Office Product sales. Wow, just like people defended GM was in the 1970s comparing to offshore competitors! These defenders completely miss the point that the marketplace is now rapidly shifting to new solutions, and the companies driving that shift with the most product are Apple, Google and Research in Motion (RIM)! Microsoft may look like Goliath, but it would be foolish to ignore the slings of new technology being brought to the battle by these David's with their smartphones, Chrome O/S, mail products, etc.

I was struck this week at the backward thinking offered on the Harvard Business Review blog posting "Is This Innovation Too Disruptive for My Firm." The author justifies companies sticking to their defensive positions, just as Microsoft is doing, simply because most companies fail at moving away from their "core." He seems very content to offer that since most companies can't really move into new markets well, so they might as well not try. Exactly what they are supposed to do as revenues dwindle in their "core" markets he never resolves! I guess he'd rather management simply not try to grow, and go down valiantly with the sinking ship.

Quite concerning is that he takes up the mantle of "core capability." He points out that most of the failures happen when companies move away from their "core" and therefore he recommends that all innovation remain close to the "core." His big argument is that this is lower risk. Well, Xerox remained close to core with laser printers – and how'd that work out for long-term value growth? Apple remained close to its Macintosh core and was almost bankrupt in 2000 before jumping into music and smartphones. Polaraoid stayed close to its core of instant film photography, and Kodak stayed close to its similar core. Now one is erased from the marketplace and the other is a no-growth inconsequential competitor.

Analogies are risky, but here goes. For the HBR author, his arguement isn't a lot different than "Over the last 200 years we've noticed that ships which sail out past the horizon often never return. Therefore, we recommend you never sail beyond the horizon. Clearly, this is risky and returns are uncertain – so don't do it. Ever. Very likely, there is nothing out there you will ever capture of value." Sort of sounds like those who wouldn't back Columbus – good thing he finally convinced Queen Isabella to give him 3 ships.

In 2008 and 2009 we've seen many great companies driven to bad returns. Layoffs abound. Growth has disappeared. Listen to HBR, and behave like Microsoft, and you'll never grow again. In 2010 we need a different approach – a different solution. Companies must realize that focusing on "core" capabilities, customers and markets has rapidly diminishing returns these days. You cannot succeed by focusing on Defending your business – even if it is a near-monopoly like PC operating systems! Why not? Because markets rapidly shift to new solutions that obsolete your products and even when you have high share, and high margins, sales can disappear really fast (like Xerox machine sales or amateur film sales – and probably laptop sales). If you aren't putting a big chunk of resources into GROWING in new marketplaces, by using White Space teams to drive that learning and growth, you will eventually become an historical artifact.

by Adam Hartung | Jan 12, 2010 | Defend & Extend, In the Swamp, Innovation, Leadership, Lock-in

Do all good ideas originate outside the organization? Of course not. Motorola understood all the critical technologies for smart phones, and taught Apple how to use them in a joint development project that created the ROKR. That's just one example of a company that had the idea for growth, but didn't move forward effectively. In this case Apple captured the value of new technology and a market shift.

On the Harvard Business Review blog site one of consulting firm Innosight's leaders, Mark Johnson, covers two stories of companies that had all the technology and capability to lead their markets, but got Locked-in to old practices. In "Have You Already Killed Your Next Big Thing" Mr. Johnson talks about Xerox and Kodak – two stories profiled in my 2008 book "Create Marketplace Disruption." Both companies developed the technology that replaced their early products (Xerox developed desktop publishing and Kodak developed the amateur digital camera.) But Lock-in kept them doing what they did rather than exploiting their own innovation.

One of the causes is a fascination with metrics. Again on the Harvard Business Review blog site Roger Martin, Dean of the Rotman School of Management at the University of Toronto, tells us in "Why Good Spreadsheets Make Bad Strategies" that you can't measure everything. And often the most important information about markets and what you must do to succeed is beyond measuring – at least in the short term.

Measurements are good control tools. Measurements can help force a focus on short term improvements. But measurements, and the concomitant focus, reduces an organization's ability to look laterally. They lose sight of information from lost customers, from small customers, from fringe customers and fringe competitors. Measurement often leads to obsession, and a deepening of Defend & Extend behavior. It's not accidental that doctors often find anorexia patients measure everything in (liquids and solids) and everything out (liquids and solids).

Measurements are created when a business is doing well. In the Rapids. Like Kodak during the 1960s and Xerox in the 1970s. Measurements are structural Lock-ins that help "institutionalize" the behavior which makes the Success Formula operate most effectively. And they help growth. But they do nothing for recognizing a market shift, and when new technology comes along, they stand in the way. That's why a powerful Six Sigma or Total Quality Management (TQM) or Lean Manufacturing project can help reduce costs short term, but become an enormous barrier to innovation over time when markets shift. These institutionalized efforts keep people doing what they measure, even if it doesn't really add much incremental value any longer.

To overcome measurement Lock-ins we all have to use scenario planning. Scenarios can help us see that in a future marketplace, a changed marketplace, measuring what we've been doing won't aid success. And because we don't yet know what the future market will really look like, we can't just swap out existing metrics for something different. As we proceed to do new things, in White Space, it's about learning what the right metrics are – about getting into the growth Rapids – before we tie ourselves up in metrics.

Note: To all readers of my Forbes article last week – there has been an update. The very professional and polite leadership at Tribune Corporation took the time to educate me about the LBO transition. As a result I learned that what I previously read, and reported in my column as well as on this blog, as being an investment of employee retirement funds into the LBO was inaccurate. Although Tribune is in hard times right now, the very good news is that the employee retirement funds were NOT wiped out by the bankruptcy. The Forbes article has been corrected, and I am thankful to the Tribune Corporation for helping me report accurately on that issue.

Chart source BusinessInsider.com