by Adam Hartung | Mar 28, 2017 | In the Rapids, Innovation, Investing, Leadership

(Photo: General Electric CEO Jeffrey Immelt, ERIC PIERMONT/AFP/Getty Images)

General Electric stock had a small pop recently when investors thought CEO Jeffrey Immelt might be pushed out. Obviously more investors hope the CEO leaves than stays. And it appears clear that activist investor Nelson Peltz of Trian Partners thinks it is time for a change in CEO atop the longest running member of the Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA.)

You can’t blame investors, however. Since he took over the top job at General Electric in 2001 (16 years ago) GE’s stock value has dropped 38%. Meanwhile, the DJIA has almost doubled. Over that time, GE has been the greatest drag on the DJIA, otherwise the index would be valued even higher! That is terrible performance — especially as CEO of one of America’s largest companies.

But, after 16 years of Immelt’s leadership, there’s a lot more wrong than just the CEO at General Electric these days. As the JPMorgan Chase analyst Stephen Tusa revealed in his analysis, these days GE is actually overvalued, “cash is weak, margins/share of customer wallet are already at entitlement, the sum of the parts valuation points to a low 20s stock price.” He goes on to share his pessimism in GE’s ability to sell additional businesses, or create cost lowering synergies or tax strategies.

Former Chairman and CEO of General Electric Jack Welch. (AP Photo/Richard Drew)

What went so wrong under Immelt? Go back to 1981. GE installed Jack Welch as its new CEO. Over the next 20 years there wasn’t a business Neutron Jack wouldn’t buy, sell or trade. CEO Welch understood the importance of growth. He bought business after business, in markets far removed from traditional manufacturing, building large positions in media and financial services. He expanded globally, into all developing markets. After businesses were acquired the pressure was relentless to keep growing. All had to be no. 1 or no. 2 in their markets or risk being sold off. It was growth, growth and more growth.

Welch’s focus on growth led to a bigger, more successful GE. Adjusted for splits, GE stock rose from $1.30 per share to $46.75 per share during the 20 year Welch leadership. That is an improvement of 35 times – or 3,500%. And it wasn’t just due to a great overall stock market. Yes, the DJIA grew from 973 to 10,887 — or about 10.1 times. But GE outperformed the DJIA by 3.5 times (350%). Not everything went right in the Welch era, but growth hid all sins — and investors did very, very, very well.

Under Welch, GE was in the rapids of growth. Welch understood that good operating performance was not enough. GE had to grow. Investors needed to see a path to higher revenues in order to believe in long term value creation. Immediate profits were necessary but insufficient to create value, because they could be dissipated quickly by new competitors. So Welch kept the headquarters team busy evaluating opportunities, including making some 600 acquisitions. They invested in things that would grow, whether part of historical GE, or not.

Jeff Immelt as CEO took a decidedly different approach to leadership. During his 16 year leadership GE has become a significantly smaller company. He sold off the plastics, appliances and media businesses — once good growth providers — in the name of “refocusing the company.” Plans currently exist to sell off the electrical distribution/grid business (Industrial Solutions) and water businesses, eliminating another $5 billion in annual revenue. He has dismantled the entire financial services and real estate businesses that created tremendous GE value, because he could not figure out how to operate in a more regulated environment. And cost cutting continues. In the GE Transportation business, which is supposed to remain, plans have been announced to double down on cost cutting, eliminating another 2,900 jobs.

Under Immelt GE has focused on profits. Strategy turned from looking outside, for new growth markets and opportunities, to looking inside for ways to optimize the company via business sales, asset sales, layoffs and other cost cutting. Optimizing the business against some sense of an historical “core” caused nearsighted — and shortsighted — quarterly actions, financial gyrations and transactions rather than building a sustainable, growing revenue stream. Under Immelt sales did not just stagnate, sales actually declined while leadership pursued higher margins.

By focusing on the “core” GE business (as defined by Immelt) and pursuing short term profit maximization, leadership significantly damaged GE. Nobody would have ever imagined an activist investor taking a position in Welch’s GE in an effort to restructure the company. Its sales growth was so good, its prospects so bright, that its P/E (price to earnings) multiple kept it out of activist range.

But now the vultures see the opportunity to do an even bigger, better job of whacking up GE — of tearing it into small bits while killing off all R&D and innovation — like they did at DuPont. Over 16 years Immelt has weakened GE’s business — what was the most omnipresent industrial company in America, if not the world – to the point that it can be attacked by outsiders ready to chop it up and sell it off in pieces to make a quick buck.

Thomas Edison, one of the world’s great inventors, innovators and founder of GE, would be appalled. That GE needs now, more than ever, is a leader who understands you cannot save your way to prosperity, you have to invest in growth to create future value and increase your equity valuation.

In May, 2012 (five years ago) I warned investors that Immelt was the wrong CEO. I listed him as the fourth worst CEO of a publicly traded company in America. While he steered GE out of trouble during the financial crisis, he also simply steered the company in circles as it used up its resources. Then was the time to change CEOs, and put in place someone with the fortitude to develop a growth strategy that would leverage the resources, and brand, of GE. But, instead, Immelt remained in place, and GE became a lot smaller, and weaker.

At this point, it is probably too late to save GE. By losing sight of the need to grow, and instead focusing on optimizing the old business while selling assets to raise cash for reorganizations, Immelt has destroyed what was once a great innovation engine. Now that the activists have GE in their sites it is unlikely they will let it ever return to the company it once was – creating whole new markets by developing new technologies that people never before imagined. The future looks a lot more like figuring out how to maximize the value of each piece of meat as it’s carved off the GE carcass.

by Adam Hartung | Aug 27, 2015 | In the Rapids, Innovation, Investing, Leadership, Web/Tech

As market volatility reached new highs this week, CNBC began talking about something called “FANG Investing.” Most commentators showed great displeasure in the fact that prior to the recent downturn high growth companies such as Facebook, Amazon, Netflix and Google (FANG) had performed much better than all the major market indices. And, in the short burst of recent recovery these companies again seemed to be doing much better.

Coined by “CNBC Mad Money” host Jim Cramer, he felt that FANG investing was bad for investors. He said he preferred seeing a much larger group of companies would go up in value, thus representing a much more stable marketplace.

Coined by “CNBC Mad Money” host Jim Cramer, he felt that FANG investing was bad for investors. He said he preferred seeing a much larger group of companies would go up in value, thus representing a much more stable marketplace.

Sound like Wall Street gobblygook? Good. Because as an individual investor why should you care about a stable market? What you should care about is your individual investments going up in value. And if yours go up and all others go down what difference does it make?

Most financial advisers today actually confuse investors much more than help them. And nowhere is this more true than when discussing risk. All financial advisers (brokers in the old days) ask how much risk you want as an investor. If you’re smart you say “none.” Why would you want any risk? You want to make money.

Only this is the wrong answer, because most investors don’t understand the question – because the financial adviser’s definition of risk is nothing like yours.

To a broker investment risk is this bizarre term called “beta,” created by economists. They defined risk as the degree to which a stock does not move with the market index. If the S&P down 5%, and the stock goes down 5%, then they see no difference between the stock and the “market” so they say it has no risk. If the S&P goes up 3% and the stock goes up 3%, again, no risk.

But if a stock trades based on its own investor expectation, and does not track the market index, then it is considered “high beta” and your broker will say it is “high risk.” So let’s look at Apple the last 5 years. If you had put all your money into Apple 5 years ago you would be up over 200% – over 4x. Had you bought the S&P 500 Index you would be up 80%. Clearly, investing in Apple would have been better. But your adviser would say that is “high risk.” Why? Because Apple did not move with the S&P. It did much better. It is therefore considered high beta, and high risk.

You buy that?

Thus, brokers keep advising investors buy funds of various kinds. Because the investors says she wants low risk, they try to make sure her returns mirror the indices. But it begs the question, why don’t you just buy an electronic traded fund (ETF) that mirrors the S&P or Dow, and quit paying those fund fees and broker fees? If their approach is designed to have you do no better than the average, why not stop the fees and invest in those things which will exactly give you the average?

Anyway, what individual investors want is high returns. And that has nothing to do with market indices or how a stock moves compares to an index. It has to do with growth.

Growth is a wonderful thing. When a company grows it can write off big mistakes and nobody cares. It can overpay employees, give them free massages and lunches, and nobody cares. It can trade some of its stock for a tiny company, implying that company is worth a vast amount, in order to obtain new products it can push to its customers, and nobody cares. Growth hides a multitude of sins, and provides investors with the opportunity for higher valuations.

On the other hand, nobody ever cost cut a company into prosperity. Layoffs, killing products, shutting down businesses and selling assets does not create revenue growth. It causes the company to shrink, and the valuation to decline.

That’s why it is lower risk to invest in FANG stocks than those so-called low-risk portfolios. Companies like Facebook, Amazon, Netflix, Google — and Apple, EMC, Ultimate Software, Tesla and Qualcomm just to name a few others — are growing. They are firmly tied to technologies and products that are meeting emerging needs, and they know their customers. They are doing things that increase long-term value.

McDonald’s was a big winner for investors in the 1960s and 1970s as fast food exploded with the baby boomer generation. But as the market shifted McDonald’s sold off its investments in trend-linked brands Boston Market and Chipotle. Now its revenue has stalled, and its value is in decline as it shuts stores and lays off employees.

Thirty years ago GE tied its plans to trends in medical technology, financial services and media, and it grew tremendously making fortunes for its investors. In the last decade it has made massive layoffs, shut down businesses and sold off its appliance, financial services and media businesses. It is now smaller, and its valuation is smaller.

Caterpillar tied itself to the massive infrastructure growth in Asia and India, and it grew. But as that growth slowed it did not move into new businesses, so its revenues stalled. Now its value is declining as it lays off employees and shuts down business units.

Risk is tied to the business and its future expectations. Not how a stock moves compared to an index. That’s why investing in high growth companies tied to trends is actually lower risk than buying a basket of stocks — even when that basket is an index like DIA or SPY. Why should you own the low-or no-growth dogs when you don’t have to? How is it lower risk to invest in a struggling McDonald’s, GE or Caterpillar or some basket that contains them than investing in companies demonstrating tremendous revenue growth?

Good fishermen go where the fish are. Literally. Anybody can cast out a line and hope. But good fisherman know where the fish are, and that’s where they invest their bait. As an investor, don’t try to fish the ocean (the index.) Be smart, and put your money where the fish are. Invest in companies that leverage trends, and you’ll lower your risk of investment failure while opening the door to superior returns.

by Adam Hartung | Nov 19, 2014 | Current Affairs, Leadership

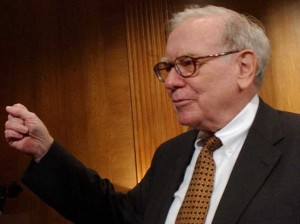

Warren Buffett is the famous head of Berkshire Hathaway. Famous because he has made himself a billionaire several times over, and made his investors excellent returns.

Berkshire Hathaway doesn’t really make anything. Rather, it owns companies that make things, or supply services. So when you buy a share of BRK you are actually buying a piece of the companies it owns, and a piece of the over $116B it invests in equities of other public companies from the cash flow of its owned entities.

Over the last decade the value of a share of BRK has increased 149%. Pretty darn good, considering the DJIA (Dow Jones Industrial Average) has only increased 64%, and the S&P 500 69%, in the same time period. So for long-term investors, putting your money with Mr. Buffett would have done more than twice as good as buying one of these leading indices.

For this reason, many investors recommend looking at what Berkshire Hathaway buys in its equity portfolio, and then buying those same stocks. On the face of it, seems smart. “Invest like Warren Buffet” one might say.

But that would be a bad idea. Berkshire Hathaway’s value has little to do with the publicly traded equities it owns. In fact, those holdings may well be a damper on BRKs valuation.

Of that giant portfolio, 4 equities make up 58% of the total holdings. Let’s look at how those have done the last decade:

- American Express (AXP,) about 10% of the portfolio, is up 83%

- Coke (KO,) about 15% of the portfolio, is up 109%

- IBM (IBM,) about 10% of the portfolio, is up 64%

- Wells Fargo (WFC,) nearly 25% of the portfolio) is up 71%

Note – not one of these stocks is up anywhere near as much as Berkshire Hathaway. There is no mathematical formula which one can use to multiply the gains on these stocks and interpret that into an overall value increase of 149%!

There are several other large, well known companies in the Berkshire Hathaway portfolio which have large (millions of shares being held) but lesser percentage positions:

- ExxonMobil (XOM) up 86%

- General Electric (GE) down <26%>

- Proctor & Gamble (PG) up 61%

- USBancorp (USB) up 40%

- USG (USG) down <30%>

- UPS up 24%

- Verizon up 38%

- Walmart up 61%

This is not to say that Berkshire Hathaway has owned all these stocks for 10 years. And, this is not all the portfolio. But it is well known that Mr. Buffett is a long-term investor who eschews short-term trading. And, these are at least randomly representative of the portfolio holdings. So by buying and selling shares at different times, and using various trading strategies, BRK’s returns could be somewhat better than the performance of these stocks. But, again, there is no arithmetic which exists that can turn the returns on these common stocks into the 149% gain which Berkshire Hathaway has achieved.

Simply put, Berkshire Hathaway makes money by doing things that no individual investor could ever accomplish. The cash flow is so enormous that Mr. Buffett is able to make deals that are not available to you, me or any other investor with less than $1B (or more likely $10B.)

When the banks looked ready to melt down in 2008 GE was in a world of hurt for money to shore up problems in its GE Capital unit. When GE went out to raise $12B via a common stock sale it turned to Mr. Buffett to lead the investment. And he did, taking a $6B position. For being so gracious, in addition to GE shares Berkshire Hathaway was able to buy $3B in preferred shares with a guaranteed dividend of 10%! Additionally, Mr. Buffett was given warrants allowing him to buy up to $3B of GE shares for a fixed price of $22.25 per share regardless of the price at which GE was trading. These are what are called “sweeteners” in the financial trade. They greatly reduce the risk on the common stock purchase, and simultaneously dramatically improve the returns.

These “sweeteners” are not available to us average, ordinary investors. And this is critical to understand. Because if someone thought that Mr. Buffett made all that money by being a good stock picker, that someone would be operating on the wrong assumption. Mr. Buffett is a very good deal maker who gets a lot more when making his investments than we get. He can do that because he can move so much money, so quickly. Faster even than any large bank.

Take, for example, the recent deal for Berkshire Hathaway to acquire the Duracell battery business from P&G. Where most of us (individuals or corporations) would have to fork over the $3B that P&G wanted, Berkshire Hathaway can simply give back P&G shares it has long held. By exchanging those shares for Duracell, Berkshire avoids paying any tax on the stock gains – thus using P&G shares in its portfolio as a currency to buy the battery business with pre-tax dollars rather than the after-tax dollars the rest of us would have to put up. In a nutshell, that saves at least 35%. But, beyond that, the deal also allows P&G to sell Duracell without having to pay tax on the assets from their end of the transaction, saving P&G 35% as well. To make the same deal, any other buyer would have been required to pay a lot more money.

Acquiring Duracell Berkshire gets 100% of another slow-growth but very good cash flow company (like Dairy Queen, Burlington Northern Rail, etc.) and does so at a very favorable price. This deal adds more cash flow to BRK, more assets to BRK, and has nothing to do with whether or not the stocks in its public equity portfolio are outperforming the DJIA or S&P.

This in no way diminishes Berkshire Hathaway, or Mr. Buffett. But it points out that many people have very bad assumptions when it comes to understanding how Mr. Buffett, or rather Berkshire Hathaway, makes money. Berkshire Hathaway is not a mutual fund, and no investor can make a fortune by purchasing common shares in the companies where Mr. Buffett invests.

Berkshire Hathaway is an extremely complicated company, and deep in its core it is an institution that has a tremendous understanding of financial instruments, financial markets, tax laws and risk. It has long owned insurance companies, and its leaders understand actuarial tables as well as how to utilize complex financial instruments and sophisticated tax opportunities to reduce risk, and raise returns, on deals that no one else could make.

By maximizing cash flow from its private holdings the Berkshire Hathaway constantly maintains a very large cash pool (currently some $60B) which it can move very, very quickly to make deals nobody, other than some of the largest private equity pools, could obtain.

The process by which Berkshire Hathaway decides to buy, hold or sell any security is unique to Berkshire Hathaway. The size of its transactions are enormous, and where we as individuals buy shares by the hundreds (the old “round lot,”) Berkshire buys millions. What stocks Berkshire Hathaway chooses to buy, hold or sell has much more to do with the unique situation of Berkshire Hathaway than stock price forecasts for those companies.

It is a myth for an individual investor to think they could invest like Mr. Buffett, and trying to emulate his returns by emulating the Berkshire portfolio is simply unwise.

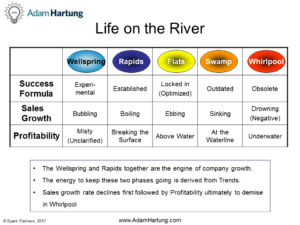

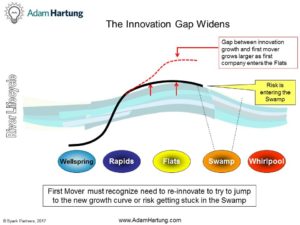

As other companies continue innovating, market growth continues (often with substitutes) but the former leader does not participate. “First Mover” advantage disappears because innovators leapfrog the creator. This gap between market growth and company growth is called the Innovation Gap. The longer the company focuses on optimization, and profit maximization, the larger the Innovation Gap becomes.

As other companies continue innovating, market growth continues (often with substitutes) but the former leader does not participate. “First Mover” advantage disappears because innovators leapfrog the creator. This gap between market growth and company growth is called the Innovation Gap. The longer the company focuses on optimization, and profit maximization, the larger the Innovation Gap becomes.