by Adam Hartung | Aug 24, 2011 | Current Affairs, Defend & Extend, In the Swamp, Innovation, Leadership, Lock-in, Web/Tech

“You’ve got to be kidding me” was the line tennis great John McEnroe made famous. He would yell it at officials when he thought they made a bad decision. I can’t think of a better line to yell at Leo Apotheker after last week’s announcements to shut down the tablet/WebOS business, spin-off (or sell) the PC business and buy Autonomy for $10.2B. Really. You’ve got to be kidding me.

HP has suffered mightily from a string of 3 really lousy CEOs. And, in a real way, they all have the same failing. They were wedded to their history and old-fashioned business notions, drove the company looking in the rear view mirror and were unable to direct HP along major trends toward future markets where the company could profitably grow!

Being fair, Mr. Apotheker inherited a bad situation at HP. His predecessors did a pretty good job of screwing up the company before he arrived. He’s just managing to follow the new HP tradition, and make the company worse.

HP was once an excellent market sensing company that invested in R&D and new product development, creating highly profitable market leading products. HP was one of the first “Silicon Valley” companies, creating enormous shareholder value by making and selling equipment (oscilliscopes for example) for the soon-to-explode computer industry. It was a leader in patent applications, new product launches and being first with products that engineers needed, and wanted.

Then Carly Fiorina decided the smart move in 2001 was to buy Compaq for $25B. Compaq was getting creamed by Dell, so Carly hoped to merge it with HP’s retail PC business and let “scale” create profits. Only, the PC business had long been a commodity industry with competitors competing on cost, and the profits largely going to Intel and Microsoft! The “synergistic” profits didn’t happen, and Carly got fired.

But she paved the way for HPs downfall. She was the first to cut R&D and new product development in favor of seeking market share in largely undifferentiated products. Why file 3,500 patents a year – especially when you were largely becoming a piece-assembly company of other people’s technology? To get the cash for acquisitions, supply chain investments and retail discounts Carly started a whole new tradition of doing less innovation, and spending a lot being a copy-cat.

But in an information economy, where almost all competitors have market access and can achieve highly efficient supply chains at low cost, there was no profit to the volume Carly sought. HP became HPQ – but the price paid was an internal shift away from investing in new markets and innovation, and heading straight toward commoditization and volume! The most valuable liquid in all creation – HP ink – was able to fund a lot of the company’s efforts, but it was rapidly becoming the “golden goose” receiving a paltry amount of feed. And itself entirely off the trend as people kept moving away from printed documents!

Mark Hurd replaced Carly, And he was willing to go her one better. If she was willing to reduce R&D and product development – well he was ready to outright slash it! And all the better, so he could buy other worn out companies with limited profits, declining share and management mis-aligned with market trends – like his 2008 $13.9B acquisition of EDS! Once a great services company, offshore outsourcing and rabid price competition had driven EDS nearly to the point of bankruptcy. It had gone through its own cost slashing, and was a break-even company with almost no growth prospects – leading many analysts to pan the acquisition idea. But Mr. Hurd believed in the old success formula of selling services (gee, it worked 20 years before for IBM, could it work again?) and volume. He simply believed that if he kept adding revenue and cutting cost, surely somewhere in there he’d find a pony!

And patent applications just kept falling. By the end of his cost-cutting reign, the once great R&D department at HP was a ghost of its former self. From 9%+ of revenues on new products, expenditures were down to under 2%! And patent applications had fallen by 2/3rds

Chart Source: AllThingsD.com “Is Innovation Dead at HP?“

The patent decline continued under Mr. Apotheker. The latest CEO intent on implementing an outdated, industrial success formula. But wait, he has committed to going even further! Now, HP will completely evacuate the PC business. Seems the easy answer is to say that consumer businesses simply aren’t profitable (MediaPost.com “Low Margin Consumers Do It Again, This Time to HP“) so HP has to shift its business entirely into the B-2-B realm. Wow, that worked so well for Sun Microsystems.

I guess somebody forgot to tell consumer produccts lacked profits to Apple, Amazon and NetFlix.

There’s no doubt Palm was a dumb acquisition by Mr. Hurd (pay attention Google.) Palm was a leader in PDAs (personal digital assistants,) at one time having over 80% market share! Palm was once as prevalent as RIM Blackberries (ahem.) But Palm did not invest sufficiently in the market shifts to smartphones, and even though it had technology and patents the market shifted away from its “core” and left Palm with outdated technology, products and limited market growth. By the time HP bought Palm it had lost its user base, its techology lead and its relevancy. Mr. Hurd’s ideas that somehow the technology had value without market relevance was another out-of-date industrial thought.

The only mistake Mr. Apotheker made regarding Palm was allowing the Touchpad to go to market at all – he wasted a lot of money and the HP brand by not killing it immediately!

It is pretty clear that the PC business is a waning giant. The remaining question is whether HP can find a buyer! As an investor, who would want a huge business that has marginal profits, declining sales, an extraordinarily dim future, expensive and lethargic suppliers and robust competitors rapidly obsoleting the entire technology? Getting out of PCs isn’t escaping the “consumer” business, because the consumer business is shifting to smartphones and tablets. Those who maintain hope for PCs all think it is the B-2-B market that will keep it alive. Getting out is simply because HP finally realized there just isn’t any profit there.

But, is the answer is to beef up the low-profit “services” business, and move into ERP software sales with a third-tier competitor?

I called Apotheker’s selection as CEO bad in this blog on 5 October, 2010 (HP and Nokia’s Bad CEO Selections). Because it was clear his history as CEO of SAP was not the right background to turn around HP. Today ERP (enterprise resource planning) applications like SAP are being seen for the locked-in, monolithic, buraucracy creating, innovation killing systems they really are. Their intent has always been, and remains, to force companies, functions and employees to replicate previous decisions. Not to learn and do anything new. They are designed to create rigidity, and assist cost cutting – and are antithetical to flexibility, market responsiveness and growth.

But following in the new HP tradition, Mr. Apotheker is reshuffling assets – closing the WebOS business, getting rid of all “consumer” businesses, and buying an ERP company! Imagine that! The former head of SAP is buying an SAP application! Regardless of what creates value in highly dynamic, global markets Mr. Apotheker is implementing what he knows how to do – operate an ERP company that sells “business solutions” while leaving everything else. He just can’t wait to get into the gladiator battle of pitting HP against SAP, Oracle, J.D. Edwards and the slew of other ERP competitors! Even if that market is over-supplied by extremely well funded competitors that have massive investments and enormously large installed client bases!

What HP desperately needs is to connect to the evolving marketplace. Quit looking at the past, and give customers solutions that fit where the market is headed. Customers aren’t moving toward where Apotheker is taking the company.

All 3 of HP’s CEOs have been a testament to just how bad things can go when the CEO is more convinced it is important to do what worked in the past, rather than doing what the market needs. When the CEO is locked-in to old thinking, old market dynamics and old solutions – rather than fixated on understanding trends, future scenarios and the solutions people want and need bad things happen.

There are a raft of unmet needs in the marketplace. For a decade HP has ignored them. Its CEOs have spent their time trying to figure out how to make old solutions work better, faster and cheaper. And in the process they have built large, but not very profitable businesses that are now uninteresting at best and largely at the precipice of failure. They have ignored market shifts in favor of doing more of the same. And the value of HP keeps declining – down 50% this year. For HP to change direction, to increase value, it needs a CEO and leadership team that can understand important trends, fulfill unmet needs and migrate customers to new solutions. HP needs to rediscover innovation.

by Adam Hartung | Aug 18, 2011 | Current Affairs, Defend & Extend, In the Swamp, Innovation, Leadership, Lifecycle, Web/Tech

The business world was surprised this week when Google announced it was acquiring Motorola Mobility for $12.5B – a 63% premium to its trading price (Crain’s Chicago Business). Surprised for 3 reasons:

- because few software companies move into hardware

- effectively Google will now compete with its customers like Samsung and HTC that offer Android-based phones and tablets, and

- because Motorola Mobility had pretty much been written off as a viable long-term competitor in the mobile marketplace. With less than 9% share, Motorola is the last place finisher – behind even crashing RIM.

Truth is, Google had a hard choice. Android doesn’t make much money. Android was launched, and priced for free, as a way for Google to try holding onto search revenues as people migrated from PCs to cloud devices. Android was envisioned as a way to defend the search business, rather than as a profitable growth opportunity. Unfortunately, Google didn’t really think through the ramifications of the product, or its business model, before taking it to market. Sort of like Sun Microsystems giving away Java as a way to defend its Unix server business. Oops.

In early August, Google was slammed when the German courts held that the Samsung Galaxy Tab 10.1 could not be sold – putting a stop to all sales in Europe (Phandroid.com “Samsung Galaxy Tab 10.1 Sales Now Blocked in Europe Thanks to Apple.”) Clearly, Android’s future in Europe was now in serious jeapardy – and the same could be true in the USA.

This wasn’t really a surprise. The legal battles had been on for some time, and Tab had already been blocked in Australia. Apple has a well established patent thicket, and after losing its initial Macintosh Graphical User Interface lead to Windows 25 years ago Apple plans on better defending its busiensses these days. It was also well known that Microsoft was on the prowl to buy a set of patents, or licenses, to protect its new Windows Phone O/S planned for launch soon.

Google had to either acquire some patents, or licenses, or serously consider dropping Android (as it did Wave, Google PowerMeter and a number of other products.) It was clear Google had severe intellectual property problems, and would incur big legal expenses trying to keep Android in the market. And it still might well fail if it did not come up with a patent portfolio – and before Microsoft!

So, Google leadership clearly decided “in for penny, in for a pound” and bought Motorola. The acquisition now gives Google some 16-17,000 patents. With that kind of I.P. war chest, it is able to defend Android in the internicine wars of intellectual property courts – where license trading dominates resolutions between behemoth competitors.

Only, what is Google going to do with Motorola (and Android) now? This acquisition doesn’t really fix the business model problem. Android still isn’t making any money for Google. And Motorola’s flat Android product sales don’t make any money either.

Source: Business Insider.com

In fact, the Android manufacturers as a group don’t make much money – especially compared to industry leader Apple:

Source: Business Insider.com

There was a lot of speculation that Google would sell the manufacturing business and keep the patents. Only – who would want it? Nobody needs to buy the industry laggard. Regardless of what the McKinsey-styled strategists might like to offer as options, Google really has no choice but to try running Motorola, and figuring out how to make both Android and Motorola profitable.

And that’s where the big problem happens for Google. Already locked into battles to maintain search revenue against Bing and others, Google recently launched Google+ in an all-out war to take on the market-leading Facebook. In cloud computing it has to support Chrome, where it is up against Microsoft, and again Apple. Oh my, but Google is now in some enormously large competitive situations, on multiple fronts, against very well-heeled competitors.

As mentioned before, what will Samsung and HTC do now that Google is making its own phones? Will this push them toward Microsoft’s Windows offering? That would dampen enthusiasm for Android, while breathing life into a currently non-competitor in Microsoft. Late to the game, Microsoft has ample resources to pour into the market, making competition very, very expensive for Google. It shows all the signs of two gladiators willing to fight to the loss-amassing death.

And Google will be going into this battle with less-than-stellar resources. Motorola is the market also ran. Its products are not as good as competitors, and its years of turmoil – and near failure – leading to the split-up of Motorola has left its talent ranks decimated – even though it still has 19,000 employees Google must figure out how to manage (“Motorola Bought a Dysfunctional Company and the Worst Android Handset Maker, says Insider“).

Acquisitions that “work” are ones where the acquirer buys a leader (technology, products, market) usually in a high growth area – then gives that acquisition the permission and resources to keep adapting and growing – what I call White Space. That’s what went right in Google’s acquisitions of YouTube and DoubleClick, for example. With Motorola, the business is so bad that simply giving it permssion and resources will lead to greater losses. It’s hard to disaagree with 24/7 Wall Street.com when divulging “S&P Gives Big Downgrade on Google-Moto Deal.”

Some would like to think of Google as creating some transformative future for mobility and copmuting. Sort of like Apple.

Yea, right.

Google is now stuck defending & extending its old businesses – search, Chrome O/S for laptops, Google+ for mail and social media, and Android for mobility products. And, as is true with all D&E management, its costs are escalating dramatically. In every market except search Google has entered into gladiator battles late against very well resourced competitors with products that are, at best, very similar – lacking game-changing characteristics. Despite Mr. Page’s potentially grand vision, he has mis-positioned Google in almost all markets, taken on market-leading and well funded competition, and set Google up for a diasaster as it burns through resources flailing in efforts to find success.

If you weren’t convinced of selling Google before, strongly consider it now. The upcoming battles will be very, very expensive. This acquisition is just so much chum in the water – confusing but not beneficial.

And if you still don’t own Apple – why not? Nothing in this move threatens the technology, product and market leader which continues bringing game-changers to market every few months.

by Adam Hartung | Aug 2, 2011 | Current Affairs, Defend & Extend, In the Whirlpool, Leadership, Lock-in

Bernie Ebbers (of WorldCom) and Jeff Skilling (of Enron) went to prison. Less well known is Conrad Black – the CEO of Sun Times Group – who also went to the pokey. What do they have in common with Rupert Murdoch – besides CEO titles? The famous claim, “I am not responsible” closely allied with “I’ve done nothing wrong.” While Murdoch hasn’t been charged with crimes, or come close to jail (yet,) there is no doubt people at News Corp have been charged, and some will go to jail. And there is public outcry Murdoch be fired.

Investors should take note; three bankruptcies killed 2 of the organizations the ex-cons led and investors were wiped out at Sun Times which barely remains in business. What will happen at News Corp? Given the commonalities between the 4 leaders, I don’t think I’d want to be a News Corp. stockholder, employee or supplier right now.

How in the world could something like this happen?

Like the infamous trio, Rupert Murdoch was, and is, a leader who defined the success formula of his company. As time passed, the growing organization became adroit at implementing the success formula, operating better, faster and cheaper. Loyal managers, who identified with, and implemented intensely, the success formula were rewarded. Those who asked questions were let go. Acquisitions were forced to conform to the success formula (such as MySpace) even if such conformance created a gap between the business and market needs. Business failure was not nearly as bad as operating outside the success formula. Failure could be forgiven – but better yet was finding a creative way to make things look successful.

Supporting the company’s success formula – its identity, cultural norms and operating methods – using all forms of ingenuity became the definition of success in these companies. This ingenuity was unbridled, even rewarded! Even when it came to skirting the edge of – or even breaking – the law. Cleverly using outsiders to do “dirty work” was an ingenious way to create plausible deniability. Financial machinations were not considered a problem if there was any way to explain changes. Violating accounting conventions not really an issue if done in the pursuit of shoring up reported results. Moving money wherever necessary to avoid taxes, or fines, and pay off executives or their friends, not really a big deal if it helped the company implement its success formula. Any behavior that reinforced the success formula, as the leader expressed it, made employees and contractors successful.

Do the ends justify the means? Of course! As long as the results appear good, and the leader is taking home a whopping amount of cash, everything appears “A-OK.”

Is this because these are crooks? Far from it. Rather, they are dedicated, hard working, industrious, smart, inventive managers who have been given a clear mission. To make the success formula work. Each small step down the ethical gangplank was a very small increment – and everyone believed they operated far from the end. If they got away with something yesterday, then why not expect to get away with a little more today? What are ethics anyway? Relative, changeable, difficult to define. Whereas fulfilling the success formula creates clear, measurable outcomes!

What is the News Corp’s Board of Directors position? The New York Times headlined “Murdoch’s Board Stands By as Scandal Widens.” Mr. Murdoch, like any good leader implementing a success formula, made sure the Board, as well as the executives and managers, were as dedicated to the success formula as he. Through that lens there are no difficult questions facing the Board. Everything was done to defend and extend the success formula. Mr. Murdoch and his team have done nothing wrong – except perhaps a zealous pursuit of implementation. What’s wrong with that? Why should the Board object?

Could this happen to you, and your organization? It may already be happening.

Answer this option, what’s more important to you and your company:

- Focusing on and identifying market trends, and adapting your strategy, tactics, products, services and processes to align with emerging future trends, or

- Focusing on execution. Setting goals, holding people to metrics and making sure implementation remains true to the company’s history, strengths and core capabilities, customers and markets? Rewarding those who meet metrics, and firing those who don’t?

If it’s the latter, it’s an easy slide into Murdoch’s very uncomfortable public seat. Very few will end up with an Enron Sized Disaster, as BNET.com headlined. But failure is likely. Any time execution is more important than questioning, implementation is more important than listening and conforming to historical norms is more important than actual business results you are chasing the select group of leaders exemplified today by Mr. Murdoch.

Here are 10 questions to ask if you want to know how at risk you just might be. If even a couple of these ring “yes,” you could be confidently, but errantly, thinking everything is OK :

- Is loyalty more important than business results? Do you have people working for you that don’t do that good a job, but do exactly what you want so you keep them?

- Do you hold certain aspects of your business as being beyond challenge – such as technology base, meeting key metrics, supporting historical distributors (or customers) or operating according to specified “rules?”

- Do you ask employees to operate according to norms before asking if they have a better idea?

- Does HR tell employees how to do things rather than asking employees what they need to succeed?

- Do employee and manager reviews have a section for asking how well they “fit” into the organization? Are people pushed out that don’t “fit?”

- Are “trusted lieutenants” moved into powerful positions over talented managers just because leaders aren’t comfortable with the newer people?

- Are certain functions (finance, HR, IT) expected (perhaps enforcers?) to make sure everyone operates according to the historical status quo?

- Is management meeting time spent predominantly on internal, versus external, issues? Talking about “how to do it” rather than “what should we do?”

- Is your advisory board, or Board of Directors, filled with your friends and co-workers that agree with your success formula and don’t seek change?

- Do your customers, employees, or suppliers learn that demonstrating dissatisfaction leads to a bad (or ended) relationship?

by Adam Hartung | Jul 28, 2011 | Books, Current Affairs, Defend & Extend, eBooks, In the Rapids, Innovation, Leadership, Television, Web/Tech

“It’s easier to succeed in the Amazon than on the polar tundra” Bruce Henderson, famed founder of The Boston Consulting Group, once told me. “In the arctic resources are few, and there aren’t many ways to compete. You are constantly depleting resources in life-or-death struggles with competitors. Contrarily, in the Amazon there are multiple opportunities to grow, and multiple ways to compete, dramatically increasing your chances for success. You don’t have to fight a battle of survival every day, so you can really grow.”

Today, Amazon(.com) is the place to be. As the financial markets droop, fearful about the economy and America’s debt ceiling “crisis,” Amazon is achieving its highest valuation ever. While the economy, and most companies, struggle to grow, Amazon is hitting record growth:

Source: BusinessInsider.com

Sales are up 50% versus last year! The result of this impressive sales growth has been a remarkable valuation increase – comparable to Apple!

- Since 2009, valuation is up 5.5x

- Over 5 years valuation is up 8x

- Over the last decade Amazon’s value has risen 15x

How did Amazon do this? Not by “sticking to its knitting” or being very careful to manage its “core.” In 2001 Amazon was still largely an on-line book seller.

The company’s impressive growth has come by moving far from its “core” into new markets and new businesses – most far removed from its expertise. Despite its “roots” and “DNA” being in U.S. books and retailing, the company has pioneered off-shore businesses and high-tech products that help customers take advantage of big trends.

Amazon’s earnings release provided insight to its fantastic growth. Almost 50% of revenues lie outside the U.S. Traditional retailers such as WalMart, Target, Kohl’s, Sears, etc. have struggled in foreign markets, and blamed poor performance on weak infrastructure and complex legal/tax issues. But where competitors have seen obstacles, Amazon created opportunity to change the way customers buy, and change the industry using its game-changing technology and capabilities. For its next move, according to Silicon Alley Insider, “Amazon is About to Invade India,” a huge retail market, in an economy growing at over 7%/year, with rising affluence and spendable income – but almost universally overlooked by most retailers due to weak infrastructure and complex distribution.

Amazon’s remarkable growth has occurred even though its “core” business of books has been declining – rather dramatically – the last decade. Book readership declines have driven most independents, and large chains such as B. Dalton and more recently Borders, out of business. But rather than use this as an excuse for weak results, Amazon invested heavily in the trends toward digitization and mobility to launch the wildly successful Kindle e-Reader. Today about half of all Amazon book sales are digital, creating growth where most competitors (hell-bent on trying to defend the old business) have dealt with stagnation and decline.

Amazon did this without a background as a technology company, an electronics company, or a consumer goods company. Additionally, Amazon invested in Kindle – and is now developing a tablet – even as these products cannibalized the historically “core” paper-based book sales. And Amazon has pursued these market shifts, even though these new products create a significant threat to Amazon’s largest traditional suppliers – book publishers.

Rather than trying to defend its old core business, Amazon has invested heavily in trends – even when these investments were in areas where Amazon had no history, capability or expertise!

Amazon has now followed the trends into a leading position delivering profitable “cloud” services. Amazon Web Services (AWS) generated $500M revenue last year, is reportedly up 50% to $750M this year, and will likely hit $1B or more before next year. In addition to simple data storage Amazon offers cloud-based Oracle database services, and even ERP (enterprise resource planning) solutions from SAP. In cloud computing services Amazon now leads historically dominant IT services companies like Accenture, CSC, HP and Dell. By offering solutions that fulfill the emerging trends, rather than competing head-to-head in traditional service areas, Amazon is growing dramatically and avoiding a gladiator war. And capturing big sales and profits as the marketplace explodes.

Amazon created 5,300 U.S. jobs last quarter. Organic revenue growth was 44%. Cash flow increased 25%. All because the company continued expanding into new markets, including not only new retail markets, and digital publishing, but video downloads and television streaming – including making a deal to deliver CBS shows and archive.

Amazon’s willingness to go beyond conventional wisdom has been critical to its success. GeekWire.com gives insight into how Amazon makes these critical resource decisions in “Jeff Bezos on Innovation” (taken from comments at a shareholder meeting June 7, 2011):

- “you just have to place a bet. If you place enough of those bets, and if you place them early enough, none of them are ever betting the company”

- “By the time you are betting the company, it means you haven’t invented for too long”

- “If you invent frequently and are willing to fail, then you never get to the point where you really need to bet the whole company”

- “We are planting more seeds…everything we do will not work…I am never concerned about that”

- “my mind never lets me get in a place where I think we can’t afford to take these bets”

- “A big piece of the story we tell ourselves about who we are, is that we are willing to invent”

If you want to succeed, there are ample lessons at Amazon. Be willing to enter new markets, be willing to experiment and learn, don’t play “bet the company” by waiting too long, and be willing to invest in trends – especially when existing competitors (and suppliers) are hesitant.

by Adam Hartung | Jun 23, 2011 | Defend & Extend, In the Swamp, In the Whirlpool, Lifecycle, Lock-in, Web/Tech

Will Cisco be like Apple and go on to continued greatness? Or will it be more like Sun Microsystems? The answer isn’t clear yet, but the negatives are looking a lot clearer than the positives.

Cisco grew like the internet – because it supplied a lot of the internet’s infrastructure. Most of those wi-fi connections, wired and wireless, were supplied by the highly talented team at Cisco. And yet today, revenues for internet routers, switches and company services for networks account for 90% of Cisco’s sales — and its non-cash value (see chart at Trefis.com.) The problem is that those markets aren’t growing like they used to, and some are shrinking, as companies are increasingly switching to common carrier services to access cloud-based services supporting corporate needs. Just like cloud-based IT architectures put risk on Microsoft PC usage, they create similar risks for private network suppliers. Even corporations, the (in)famous “enterprise” customers for Cisco, are finding they can create security and reliability by giving up proprietary networks.

The market capitalization for Cisco has plunged some 40% the last year, and over 55% since peaking in late 2007. Those who support investing in Cisco think like the SeekingAlpha.com headline “3 Reasons Why Cisco is Oversold.” They cite a huge cash hoard (some 25% of market cap) and Cisco’s dominance in its historical “core” product markets. They hope that a revived economy will create an uptick in infrastructure spending by corporations and public entities. Or big buying in emerging countries.

Detractors become vitriolic about the company’s lost valuation, blaming Chairman/CEO John Chambers in articles like the SeekingAlpha.com “Cisco, Either Chambers Goes or I Go.” Their arguments are less about product miscues, and more intensely claiming the CEO misdirected funds into bad consumer market opportunities (Flip phone,) undeveloped new projects like virtual conferencing and an overly complicated organization structure.

What Cisco really needs is more new products in growth markets. Places where demand is growing, and the company can flourish like it did in the hey-day halcyon growth days of the internet. That was why CEO Chambers implemented a market-focused organization structure – complete with multi-layered committees – in an effort to seek out growth opportunities and fund them. Only, the organization lacked the permission and resource commitment to really allow developing most new markets and was overly complex in the resource allocation process. Instead of moving rapidly to identify and develop growth, the organization stalled in endless discussions. A couple of months ago the new org was gutted in a “refocusing” effort (typical reaction: BusinessInsider.com “Cisco’s Crazy Management Structure Wasn’t Working, So Chambers is Changing It“.)

But, if the previously more open organization couldn’t find permission to identify, fund and develop new markets, how will a “more focused” organization do so? Focus isn’t going to make companies (or households) buy more switches and routers. Or buy more network consulting services. The market has shifted, so as people move to smartphones and tablets, and cloud-based apps they access over common networks, how will an organization focused on old customers and products prove more successful? While the old organization may have been problematic, is abandoning a market-focused organization going to be an improvement? Sounds like a set-up for future layoffs.

In the drive for new products Cisco bought a very successful business in the Flip camera two years ago, which according to MediaPost.com had 26% market share. But, “Flip Camera: Dream Becomes a Nightmare” details the story of how Cisco was too late. The market quickly was shifting from digital cameras to smart phones – and sales stagnated. Cisco didn’t learn much about consumer products, or smart phones or how to launch new products outside its “core” from the experience, choosing to shut the business down and withdraw the product this spring (“Cisco Kills the Flip Camera“.) Ouch!

Clearly, Flip was a financially unsuccessful venture. But that could be forgiven if Cisco learned from the experience so it could move, like Apple, toward launching something really good (like Apple did with iPods.) But we don’t hear of any organizational learning from Flip, just failure.

And that’s too bad, because Cisco’s virtual conferencing could have great promise. Most of us now hate to travel (thanks TSA and all that great airline service!) And most corporate controllers hate to pay for business travel. The trends all point toward more and more virtual conferencing. For everything from one-on-one meetings to multi-site meetings to industry conferences for learning. This is a BIG trend, that will go well beyond a simple WebEx. Someone is going to make money with this – taking Skype to an entirely new level of performance. But given how badly Cisco managed Flip, and the new “refocusing” effort, it’s hard to see how that winner will be Cisco.

Cisco’s not yet a Sun Microsystems, so locked-in to old products it cannot do anything else and unable to grow at all. It’s not yet a Dell or Microsoft that’s missed the market shifts and is trying to spend too much money, too late on weak products against well funded, fast growing and profitable competitors.

But, the signs don’t look good. There’s no discussion about what Cisco sees itself doing new and differently in 5 years. We don’t see Cisco offering leading edge products like it did 15 years ago in its old “core” market. It’s historical market is not growing like it once did, and new competitors are changing the market entirely. The layered organization was an effort to attack old sacred cows, and limit the power of old status quo police, but now the new “focused” re-organization is reversing those efforts to find new markets for growth. “Focus” rarely goes hand-in-hand with successful innovation. We cannot find an obvious group of people focusing on new markets, with permission and resources to bring out the “next big thing” that could drive a doubling of revenues by 2017.

Unlike RIMM, the game isn’t over for CSCO. It’s markets still have some longevity. But the organization has been failing at doing the kind of new things, bringing out the new innovations, that would make it a good investment. Until management shows it knows how to find new markets and launch disruptive innovations, CSCO is not a place to invest. Don’t expect a fat dividend, and don’t expect revisiting old growth rates any time soon.

There are likely to be some good, and bad quarters. Cost management, and occasional big orders, combined with manipulating the timing of revenues and costs will allow for management to say “things are all better.” But there will be miscues and problems, and blaming of competitors and weak economic conditions in the bad quarters. Defend and extend management does not work when markets shift. Sideways is not moving forward. It’s more like treading water in the ocean – not a good strategy for rescue. Overall, I wouldn’t be optimistic.

by Adam Hartung | Jun 16, 2011 | Defend & Extend, In the Whirlpool, Innovation, Leadership, Lock-in, Web/Tech

Dell is a dog. From $25/share a decade ago the company rose to around $40/share around 2005, only to collapse. The stock now trades around $15, rising from recent lows of about $10. The company’s value is only $30B, only half revenues of $61B, instead of the revenue multiple obtained by most growth stocks. But then, revenues have been flat for the last 4 years — so maybe it’s time to say Dell isn’t a growth stock any longer.

And that would be correct.

In the 1990s Dell was a darling. The company could do no wrong as its revenues and valuation soared. Founder and CEO Michael Dell was a highly desired speaker at fees of $100,000+. Michael Dell was quick to tell people his success formula, which was pretty simple:

- Do no R&D. Outsource product development to key vendors (Intel and Microsoft). Focus on price and cost. Be operationally excellent! Be the best, most focused manufacturer/assembler.

- Genericize the product. Make it easy to buy, thus cheap and easy to sell.

- Sell direct rather than through distributors so you lower sales cost.

- Use supply chain practices to drive down parts cost and inventory, making it possible to compete on price and collect your funds before paying vendors.

In short, focus on operational excellence to be really fast and cheap. Faster and cheaper than anyone else.

And this success formula worked!! As long as folks wanted personal computers, Dell was the game to beat. And the company reaped the reward of PC market growth, expanding as the PC – especially the Wintel PC – market exploded.

Dell’s problems today aren’t the result of bad management. Dell has been focused, diligent, hard working and very cost conscientuous. Dell made no horrible decisions, and made no serious mistakes in its strategy or tactics. Although for a while it was vilified for weaker support from outsourced vendors in India (again, a tactic used in all parts of Dell’s strategy) that was rectified. Largely for 2 decades Dell has continued to perform better and better at its internal metrics – its success formula.

Dell’s fall from grace was due to the market shifting. Firstly, competitors figured out how to do what Dell did pretty much as good as Dell did it. No operationally oriented strategy is immune from copy-cats, and Dell discovered other companies could do pretty much what they did. It becomes a dog-eat-dog world quickly when your discussions are all “price, delivery, service” and you can’t offer something truly unique. It may not be obvious when markets are growing, and there’s plenty of business for everyone, but oh how quickly it shows up in declining margins when growth slows.

Secondly, and more importantly, the market shifted away from Dell’s primary products. PC sales are now flat to declining, depending on marketplace, as customers shift from Wintel platforms to smartphones and tablets. Despite big acquisitions in data storage and services (to the tune of $5B the last couple of years) Dell still has 70% of its revenues in PCs (55% hardware, 15% software and services.) Most of that money was spent attempting to shore up the Dell success formula by extending its core offerings to core customers. Now all future forecasts show the market will continue to move away from PCs and toward new platforms, making it impossible to create organic growth, and pinching margins in all sectors.

So, were Dell’s executives dumb, incompetent, lethargic or some combination of all 3? Actually, none of those things – as CNNMoney.com points out in “Dell’s Dilemma“. They were simply stuck. Stuck with their own best practices, doing what they do really well, and continuing to do more of it. Unable to move forward, because most attention was focused on defending and extending the old core.

Nobody knows the Dell core better than Michael Dell. His return spells only less likelihood of success for Dell. As opportunities emerged in smartphones and other markets he found it simply easier, faster, cheaper and more consistent to wait on those markets while defending the core PC business. Key vendors Intel and Microsoft, critical to historical success, were not offering new solutions for these markets, or promoting sales in them. Key customers, the IT departments in government and corporate accounts, weren’t clamoring for these new products. They wanted more PCs that were better, faster and cheaper. Dell was looking for the divine light of perfect future understanding to change the company investments – and when it didn’t emerge he kept right on plunking money into the business headed for decline.

Inside consultants (Bain and Co. is well known to be the primary strategists and tacticians at Dell) and employee experts had never-ending opportunities to improve the Dell systems, in their efforts to defend the Dell sales against other PC competitors and seek out additional expansion opportunities in targeted offshore or niche markets. Suppliers wanted Dell to keep building and promoting PCs. And customers locked-in to old platforms were just experimenting with new solutions – far from adopting anything new in the volumes that would match historical PC sales. “If just the economy comes around, I’m sure sales will return” it’s easy to imagine everyone at Dell saying.

Now Dell is in declining products, with an outdated strategy chasing a larger competitor as margins continue to remain squeezed. Nobody wants to exit this business quickly, so prices are under ever greater pressure – especially since Android tablets are cheaper than laptops already – and smartphones can be had for free from the right wireless supplier.

It’s too late for Dell. The time to act was 5 years ago. Then Dell could have set up a team to explore the market for new solutions. Dell could have been the first to offer an Android phone or tablet – the company has plenty of smart folks who could experiment and figure it out. They could have championed the Zune, and created a download store for the product to compete with iPods and iTunes (the Zune is no longer supported by Microsoft.) But there were no resources, and no permission given to try changing the success formula.

As Chromebooks are launched (“The First Google Chromebooks are On Sale Now, Here’s Everything You Need to Know” BusinessInsider.com) Dell could have been the market leader, instead of Acer and Samsung. There’s even a chance that Dell might have blunted the huge market lead Apple created since 2005 if management had just created a team with the opportunity to really discover what people would do with these new solutions. There was a time a “strategic partnership” between Dell and Google could have been a big threat to Apple. But no longer.

Apple, which put its resources into pioneering new markets the last decade has seen its value explode many-fold. It’s value is over 10x Dell. Apple has enough cash to buy Dell outright. But why would it? Dell has become a niche player – and due to its lock-in to historical best practices and its old success formula has no opportunities to grow.

All companies risk becoming marginalized. Focusing on your core products, core technology vendors and core customers leads to blindness about the possibility of market shifts. You can work yourself to death, be focused and diligent, and remain dedicated to constant improvement — even excellence! But when markets shift it’s easy to become obsolete, and fall into margin killing price wars as growth stagnates. Just look at Dell. From darling to dog in just 10 years.

If you still own DELL, the recent price rise makes this a great time to SELL. Dell has no new products, and no idea how to move into new markets. It’s commitment to its core is a death knell. And without white space to do anything new, it can/t (and won’t) transform itself into a winner.

by Adam Hartung | Jun 3, 2011 | Current Affairs, Defend & Extend, In the Rapids, In the Swamp, In the Whirlpool, Leadership, Lock-in, Web/Tech

Were you ever told “pretty is as pretty does?” This homily means “don’t just look at the surface, it’s the underlying qualities that matter.” When I read analyst reviews of companies I’m often struck by how fascinated they are with the surface, and how weakly they seem to understand the underlying markets. Financials are a RESULT of management’s ability to provide competitive solutions, and no study of financials will give investors a true picture of management or the company’s future prospects.

The good:

Everyone should own Apple. The list of its market successes are clear, and well detailed at SeekingAlpha.com “Apple: The Most Undervalued Equity in Techdom.” The reason you should own Apple isn’t its past performance, but rather that the company has built a management team completely focused on the future. Apple is using scenario planning to create solutions that fit the way people want to work and live – not how they did things in the past.

And Apple managers are obsessive about staying ahead of competitors with better solutions that introduce new technologies, and higher levels of user productivity. By constantly being willing to disrupt the old ways of doing things, Apple keeps bringing better solutions to market via its ongoing investment in teams dedicated to developing new solutions and figuring out how they will adapt to fit unmet needs. And this isn’t just a “Steve Jobs thing” as the company’s entire success formula is built on the ability to plan for the future, and outperform competitors. We are seeing this now with the impending launch of iCloud (Marketwatch.com “Could Apple Still Surprise at Its Conference?“)

For nearly inexplicable reasons, many investors (and analysts) have not been optimistic about Apple’s future price. The company’s earnings have grown so fast that a mere fear of a slow-down has caused investors to retrench, expecting some sort of inexplicable collapse. Analysts look for creative negatives, like a recent financial analyst told me “Apple is second in value only to ExxonMobile, and I’m just not sure how to get my mind around that. Is it possible growth could be worth that much? I thought value was tied to assets.”

Uh, yes, growth is worth that much! Apple’s been growing at 100%. Perhaps it won’t continue to grow at that breakneck pace (or perhaps it will, there’s no competitor right now blocking its path), but even if it slows by 75% we’re still talking 25% growth – and that creates enormous value (compounded, 25% growth doubles your investment in 3 years.) When you find profitable growth from a company designed to repeat itself with new market introductions, you have a beautiful thing! And that’s a good investment.

Similarly, investors should really like Netflix. Netflix did what almost nobody does. It overcame fears of cannibalizing its base business (renting DVDs via mail-order) and introduced a streaming download service. Analysts decried this move, fearing that “digital sales would be far lower than physical sales.” But Netflix, with its focus firmly on the future and not the past, recognized that emerging competitors (like Hulu) were quickly changing the game. Their objective had to be to go where the market was heading, rather than trying to preserve an historical market destined to shrink. That sort of management thinking is a beautiful thing, and it has paid off enormously for Netflix.

Of course, those who look only at the surface worry about the pricing model at Netflix. They mostly worry that competitors will gore the Netflix digital ox. But what we can see is that the big competitors these analysts trot out for fear mongering – Wal-Mart, Amazon.com and Comcast – are locked-in to historical approaches, and not aggressively taking on Netflix. When you look at who has the #1 market position, the eyes and ears of customers, the subscriber/customer base and the delivery solution customers love you have to be excited about Netflix. After all, they are the leaders in a market that we know is going to shift their way – downloads. Sort of reminds you of Apple when they brought out the iPod and iTunes, doesn’t it?

The bad:

Google has been a great company. The internet wouldn’t be the internet if we didn’t have Google, the search engine that made the web easy and fast to use, plus gave us the ads making all of that search (and lots of content) free. But, the company has failed to deliver on its own innovations. Android is a huge market success, but unfortunately lock-in to its old mindset led Google to give the product away – just a tad underpriced. Other products, like Wave were great, but there hasn’t been enough White Space available for the products to develop into commercial successes. And we’ve all recently read how it happened that Google missed the emergence of social media, now positioning Facebook as a threaten to their long-term viability (AllThingsD.com “Schmidt Says Google’s Social Networking Problem is His Fault.“)

Chrome, Chromebooks and Google Wallet could be big winners. And there’s a new CEO in place who promises to move Google beyond its past glory. But these are highly competitive markets, Google isn’t first, it’s technology advantages aren’t as clear cut as in the old search days (PCWorld.com “Google Wallet Isn’t the Only Mobile POS Tool.”) Whether Google will regain its past glory depends on whether the company can overcome its dedication to its old success formula and actually disrupt its internal processes enough to take the lead with disruptive marketplace products.

Cisco is in a similar situation. A great innovator who’s products put us all on the web, and made us wi-fi addicted. But markets are shifting as people change their needs for costly internal networks, moving to the cloud, and other competitors (like NetApp) are the game changers in the new market. Cisco’s efforts to enter new markets have been fragmented, poorly managed, and largely ineffective as it spent too much energy focused on historical markets. Emblematic was the abandoned effort to enter consumer markets with the Flip camera, where its inability to connect with fast shifting market needs led to the product line shutdown and a loss of the entire investment (BusinessInsider.com “Cisco Kills the Flip Camera.”)

Cisco’s value is tied not to its historical market, but its ability to develop new ones. Even when they likely cannibalize old products. HIstorically Cisco did this well. But as customers move to the cloud it’s still not clear what Cisco will do to remain an industry leader. Whether Google and Cisco will ever be good investments again doesn’t look too good, today. Maybe. But only if they realign their investments and put in place teams dedicated to new, growth markets.

The ugly:

Another homily goes “beauty may be on the surface, but ugly goes clear to the bone.” Meaning? For something to be ugly, it has to be deeply flawed inside. And that’s the situation at Research in Motion and Microsoft. Optimistic investors describe both of these companies as potential “value stocks” that will find a way to “protect the installed base as an economic recovery develops” and “sell their products cheaply in developing countries that can’t afford new solutions” eventually leading to high dividend payouts as they milk old businesses. Right. That won’t happen, because these companies are on a self-destructive course to preserve lost markets which will eat up resources and leave them shells of their former selves.

Both companies were wildly successful. Both once had near-monopolies in their markets. But in both cases, the organizations became obsessed with defending and extending sales to their “core” or “base” customers using “core” technologies and products. This internal focus, and desire to follow best practices, led them to overspending on what worked in the past, while the market shifted away from them.

At RIMM the market has moved from enterprise servers and secure enterprise applications to local apps that access data via the cloud. People have moved from PCs to smartphones (and tablets) that allow them to do even more than they could do on old devices, and RIM’s devotion to its historical business base caused the company to miss the shift. Blackberry and Playbook have 1/10th the apps of leaders Apple and Android (at best) and are rapidly being competitively outrun.

Likewise, Microsoft has offered the market nothing new when it comes to emerging markets and unmet user needs as it has invested billions of dollars trying to preserve its traditional PC marketplace. Vista, Windows 7 and Office 2010 all missed the fact that users were going off the PC, and toward new solutions for personal productivity. Now the company is trying to play catch-up with its Skype acquisition, Nokia partnership (where sales are in a record, multi-year slide; SeekingAlpha.com “Nokia Deluged with Downgrades“) and a planned launch of Windows 8. Only they are against ferocious competition that has developed an enormous market lead, using lower cost technologies, and keep offering innovations that are driving additional market shift.

Companies that plan for the future, keep their eyes firmly focused on unmet needs and alternative competitors, and that accept and implement disruptions via internal teams with permission to be game-changers are the winners. They are good investments.

Big winners that keep seeking new opportunities, but fall into over-reliance (and focus) on historical markets and customers can move from being good investments to bad ones. They have to change their planning and competitive analysis, and start attacking old notions about their business to free up resources for doing new things. They can return to greatness, but only if they recognize market shifts and move aggressively to develop solutions for emerging needs in new markets.

It gets ugly when companies lose their ability to see external market shifts because they are inwardly focused (inside their organizations, and inside their historical customer base or supply chain.) Their market sensing disappears, and their investments become committed on trying to defend old businesses in the face of changes far beyond their control. Their internal biases cause reduction of shareholder value as they spend money on acquisitions and new products that have negative rates of return in their overly-optimistic effort to regain past glory. Those situations almost never return to former beauty, as ugly internal processes lock them into repeating past behaviors even when its clear they need an entirely new approach to succeed.

by Adam Hartung | May 25, 2011 | Defend & Extend, Disruptions, In the Swamp, Innovation, Leadership, Lock-in, Openness, Transparency, Web/Tech

Nobody admits to being the innovation killer in a company. But we know they exist. Some these folks “dinosaurs that won’t change.” Others blame “the nay-saying ‘Dr. No’ middle managers.” But when you meet these people, they won’t admit to being innovation killers. They believe, deep in their hearts as well as in their everyday actions, that they are doing the right thing for the business. And that’s because they’ve been chosen, and reinforced, to be the Status Quo Police.

When a company starts it has no norms. But as it succeeds, in order to grow quickly it develops a series of “key success factors” that help it continue growing. In order to grow faster, managers – often in functional roles – are assigned the task of making sure the key success factors are unwaveringly supported. Consistency becomes more important than creativity. And these managers are reinforced, supported, even bonused for their ability to make sure they maintain the status quo. Even if the market has shifted, they don’t shift. They reinforce doing things according to the rules. Just consider:

Quality – Who can argue with the need to have quality? Total Quality Management (TQM,) Continuous Improvement (CI,) and Six Sigma programs all have been glorified by companies hoping to improve product or service quality. If you’re trying to fix a broken product, or process, these work pretty well at helping everyone do their job better.

But these programs live with the mantra “if you can’t measure it, you can’t improve it. Measure everything that’s important.” If you’re innovating, what do you measure? If you’re in a new technology, or manufacturing process, how do you know what you really need to do right? If you’re in a new market, how do you know the key metric for sales success? Is it number of customers called, time with customers, number of customer surveys, recommendation scores, lost sales reports? When you’re trying to do something new, a lot of what you do is respond quickly to instant feedback – whether it’s good feedback or bad.

The key to success isn’t to have critical metrics and measure performance on a graph, but rather to learn from everything you do – and usually to change. Quality people hate this, and can only stand in the way of trying anything new because you don’t know what to measure, or what constitutes a “good” measure. Don’t ever forget that Motorola pretty much invented Six Sigma, and what happened to them in the mobile phone business they pioneered?

Finance. All businesses exist to make money, so who can argue with “show me the numbers. Give me a business plan that shows me how you’re going to make money.” When your’e making an incremental investment to an existing asset or process, this is pretty good advice.

But when you’re innovating, what you don’t know far exceeds what you know. You don’t know how to meet unment needs. You don’t know the market size, the price that people will pay, the first year’s volume (much less year 5,) the direct cost at various volumes, the indirect cost, the cost of marketing to obtain customer attention, the number of sales calls it will take to land a sale, how many solution revisions will be necessary to finally put out the “right” solution, or how sales will ramp up quarterly from nothing. So to create a business plan, you have to guess.

And, oh boy, then it gets ugly. “Where did this number come from? That one? How did you determine that?” It’s not long until the poor business plan writer is ridden out of the meeting on a rail. He has no money to investigate the market, so he can’t obtain any “real” numbers, so the business plan process leads to ongoing investment in the old business, while innovation simply stalls.

Under Akia Morita Sony was a great innovator. But then an MBA skilled in finance took over the top spot. What once was the #1 electronics innovator in the globe has become, well, let’s say they aren’t Apple.

Legal – No company wants to be sued, or take on unnecessary risk. And when you’re selling something, lawyers are pretty good at evaluating the risk in that business, and lowering the risk. While making sure that all the compliance issues are met in order to keep regulators – and other lawyers – out of the business.

But when you’re starting something new, everything looks risky. Customers can sue you for any reason. Suppliers can sue you for not taking product, or using it incorrectly. The technology could fail, or have negative use repercussions. Reguators can question your safety standards, or claims to customers.

From a legal point of view, you’re best to never do anything new. The less new things you do, the less likely you are to make a mistake. So legal’s great at putting up roadblocks to make sure they protect the company from lawsuits, by making sure nothing really new happens. The old General Motors had plenty of lawyers making sure their cars were never too risky – or interesting.

R&D or Product Development – Who doesn’t think it’s good to be a leader in a specific technology? Technology advances have proven invaluable for companies in industries from computers to pharmaceuticals to tractors and even services like on-line banking. Thus R&D and Product Development wants to make sure investments advance the state of the technology upon which the company was built.

But all technologies become obsolete. Or, at least unprofitable. Innovators are frequently on the front end of adopting new technologies. But if they have to obtain buy-in from product development to obtain staffing or money they’ll be at the end of a never-ending line of projects to sustain the existing development trend. You don’t have to look much further than Microsoft to find a company that is great at pouring money into the PC platform (some $9B, 16% of revenue in 2009,) while the market moves faster each year to mobile devices and entertainment (Apple spent 1/8th the Microsoft budget in 2009.)

Sales, Marketing & Distribution – When you want to protect sales to existing customers, or maybe increase them by 5%, then doing more of what you’ve always done is smart. So money is spent to put more salespeople on key accounts, add more money to the advertising budget for the most successful (or most profitable) existing products. There are more rules about using the brand than lighters at a smoker’s convention. And it’s heresy to recommend endangering the distribution channel that has so successfully helped increase sales.

But innovators regularly need to behave differently. They need to sell to different people – Xerox sold to secretaries while printing press manufacturers sold to printers. The “brand” may well represent a bygone era, and be of no value to someone launching a new product; are you eager to buy a Zenith electronic device? Sprucing up the brand, or even launching something new, may well be a requirement for a new solution to be taken seriously.

And often, to be successful, a new solution needs to cut through the old, high-cost distribution system directly to customers if it is to succeed. Pre-Gerstner IBM kept adding key account sales people in hopes of keeping IT departments from switching out of mainframes to PCs. Sears avoided the shift to on-line sales successfully – and revenue keeps dropping in the stores.

Information Technology – To make more money you automate more functions. Computers are wonderful for reducing manpower in many tasks. So IT implements and supports “standard solutions” that are cost effective for the historical business. Likewise, they set up all kinds of user rules – like don’t go to Facebook or web sites from work – to keep people focused on productivity. And to make sure historical data is secure and regulations are met.

But innovators don’t have a solution mapped out, and all that automated functionality is an enormously expensive headache. When being creative, more time is spent looking for something new than trying to work faster, or harder, so access to more external information is required. Since the solution isn’t developed, there’s precious little to worry about keeping secure. Innovators need to use new tools, and have flexibility to discover advantageous ways to use them, that are far beyond the bounds of IT’s comfort zone.

Newspapers are loaded with automated systems to collect and edit news, to enter display ads, and to “Make up” the printed page fast and cheap. They have automated systems for classified advertising sales and billing, and for display ad billing. And systems to manage subscribers. That technology isn’t very helpful now, however, as newspapers go bankrupt. Now the most critical IT skills are pumping news to the internet in real-time, and managing on-line ads distributed to web users that don’t have subscriptions.

Human Resources – Growth pushes companies toward tighter job descriptions with clear standards for “the kinds of people that succeed around here.” When you want to hire people to be productive at an existing job, HR has the procedures to define the role, find the people and hire them at the most efficient cost. And they can develop a systematic compensation plan that treats everyone “fairly” based upon perceived value to the historical business.

But innovators don’t know what kinds of people will be most successful. Often they need folks who think laterally, across lots fo tasks, rather than deeply about something narrow. Often they need people who are from different backgrounds, that are closer to the emerging market than the historical business. And pay has to be related to what these folks can get in the market, not what seems fair through the lens of the historical business. HR is rarely keen to staff up a new business opportunity with a lot of misfits who don’t appreciate their compensation plan – or the rules so carefully created to circumscribe behavior around the old business.

B.Dalton was America’s largest retail book seller when Amazon.com was founded by Jeff Bezos. Jeff knew nothing about books, but he knew the internet. B.Dalton knew about books, and claimed it knew what book buyers wanted. Two years later B.Dalton went bankrupt, and all those book experts became unemployed. Amazon.com now sells a lot more than books, as it ongoingly and rapidly expands its employee skill sets to enter new markets – like publishing and eReaders.

Innovation requires that leaders ATTACK the Status Quo Police. Everything done to efficiently run the old business is irrelevant when it comes to innovation. Functional folks need to be told they can’t force the innovatoirs to conform to old rules, because that’s exactly why the company needs innovation! Only by attacking the old rules, and being willing to allow both diversity and disruption can the business innovate.

Instead of saying “this isn’t how we do things around here” it is critical leaders make sure functional folks are saying “how can I help you innovate?” What was done in the name of “good business” looks backward – not forward. Status Quo cops have to be removed from the scene – kept from stopping innovation dead in its tracks. And if the internal folks can’t be supportive, that means keeping them out of the innovator’s way entirely.

Any company can innovate. Doing so requires recognizing that the Status Quo Police are doing what they were hired to do. Until you take away their clout, attack their role and stop them from forcing conformance to old dictums, the business can’t hope to innovate.

by Adam Hartung | May 16, 2011 | Defend & Extend, In the Swamp, Leadership, Lifecycle, Lock-in, Web/Tech

In “Screening Large Cap Value Stocks” 24x7WallSt.com tries making the investment case for Dell. And backhandedly, for Hewlett Packard. The argument is as simple as both companies were once growing, but growth slowed and now they are more mature companies migrating from products into services. They have mounds of cash, and will soon start paying a big, fat dividend. So investors can rest comfortably that these big companies are a good value, sitting on big businesses, and less risky than growth stocks.

Nice story. Makes for good myth. Reality is that these companies are a lousy value, and very risky.

Dell grew remarkably fast during the PC growth heyday. Dell innovated computer sales, eschewing expensive distribution for direct-to-customer marketing and order-taking. Dell could sell individuals, or corporations, computers off-the-shelf or custom designed machines in minutes, delivered in days. Further, Dell eschewed the costly product development of competitors like Compaq in favor of using a limited number of component suppliers (Microsoft, Intel, etc.) and focusing on assembly. With Wal-Mart style supply chain execution Dell could deliver a custom order and be paid before the bill was due for parts. Quickly Dell was a money-making, high growth machine as it rode the growth of PC sales expansion.

But competitors learned to match Dell’s supply chain cost-cutting capabilities. Manufacturers teamed with retailers like Best Buy to lower distribution cost. As competition copied the use of common components product differences disappeared and prices dropped every month. Dell’s advantages started disappearing, and as they continued to follow the historical cost-cutting success formula with more outsourcing, problems developed across customer services. Competitors wreaked havoc on Dell’s success formula, hurting revenue growth and margins.

HP followed a similar path, chasing Dell down the cost curve and expanding distribution. To gain volume, in hopes that it would create “scale advantages,” HP acquired Compaq. But the longer HP poured printer profits into PCs, the more it fed the price war between the two big companies.

Worst for both, the market started shifting. People bought fewer PCs. Saturation developed, and reasons to buy new ones were few. Users began buying more smartphones, and later tablets. And neither Dell nor HP had any products in development where the market was headed, nor did their “core” suppliers – Microsoft or Intel.

That’s when management started focusing on how to defend and extend the historical business, rather than enter growth markets. Rather than moving rapidly to push suppliers into new products the market wanted, both extended by acquiring large consulting businesses (Dell famously bought Perot Systems and HP bought EDS) in the hopes they could defend their PC installed base and create future sales. Both wanted to do more of what they had always done, rather than shift with emerging market needs.

But not only product sales were stagnating. Services were becoming more intensely competitive – from domestic and offshore services providers – hampering sales growth while driving down margins. Hopes of regaining growth in the “core” business – especially in the “core” enterprise markets – were proving illusory. Buyers didn’t want more PCs, or more PC services. They wanted (and now want) new solutions, and neither Dell nor HP is offering them.

So the big “cash hoard” that 24×7 would like investors to think will become dividends is frittered away by company leadership – spent on acquisitions, or “special projects,” intended to save the “core” business. When allocating resources, forecasts are manipulated to make defensive investments look better than realistic. Then the “business necessity” argument is trotted out to explain why acquisitions, or price reductions, are necessary to remain viable, against competitors, even when “the numbers” are hard to justify – or don’t even add up to investor gains. Instead of investing in growth, money is spent trying to delay the market shift.

Take for example Microsoft’s recent acquisition of Skype for $8.5B. As Arstechnia.com headlined “Why Skype?” This acquisition is another really expensive effort by Microsoft to try keeping people using PCs. Even though Microsoft Live has been in the market for years, Microsoft keeps trying to find ways to invest in what it knows – PCs – rather than invest in solutions where the market is shifting. New smartphone/tablet products come with video capability, and are already hooked into networks. Skype is the old generation technology, now purchased for an enormous sum in an effort to defend and extend the historical base.

There is no doubt people are quickly shifting toward smartphones and tablets rather than PCs. This is an irreversable trend:  Chart source BusinessInsider.com

Chart source BusinessInsider.com

Executive teams locked-in to defending their past spend resources over-investing in the old market, hoping they can somehow keep people from shifting. Meanwhile competitors keep bringing out new solutions that make the old obsolete. While Microsoft was betting big on Skype last week Mediapost.com headlined “Google Pushes Chromebook Notebooks.” In a direct attack on the “core” customers of Dell and HP (and Microsoft) Google is offering a product to replace the PC that is far cheaper, easier to use, has fewer breakdowns and higher user satisfaction.

Chromebooks don’t have to replace all PCs, or even a majority, to be horrific for Dell and HP. They just have to keep sucking off all the growth. Even a few percentage points in the market throws the historical competitors into further price warring trying to maintain PC revenues – thus further depleting that cash hoard. While the old gladiators stand in the colliseum, swinging axes at each other becoming increasingly bloody waiting for one to die, the emerging competitors avoid the bloodbath by bringing out new products creating incremental growth.

People love to believe in “value stocks.” It sounds so appealing. They will roll along, making money, paying dividends. But there really is no such thing. New competitors pressure sales, and beat down margins. Markets shift wtih new solutions, leaving fewer customers buying what all the old competitors are selling, further driving down margins. And internal decision mechanisms keep leadership spending money trying to defend old customers, defend old solutions, by making investments and acquisitions into defensive products extending the business but that really have no growth, creating declining margins and simply sucking away all that cash. Long before investors have a chance to get those dreamed-of dividends.

This isn’t just a high-tech story. GM dominated autos, but frittered away its cash for 30 years before going bankrupt. Sears once dominated retailing, now its an irrelevent player using its cash to preserve declining revenues (did you know Woolworth’s was a Dow Jones company until 1997?). AIG kept writing riskier insurance to maintain its position, until it would have failed if not for a buyout. Kodak never quit investing in film (remember 110 cameras? Ektachrome) until competitors made film obsolete. Xerox was the “copier company” long after users switched to desktop publishing and now paperless offices.

All of these were once called “value investments.” However, all were really traps. Although Dell’s stock has gyrated wildly for the last decade, investors have lost money as the stock has gone from $25 to $15. HP investors have fared a bit better, but the long-term trending has only had the company move from about $40 to $45. Dell and HP keep investing cash in trying to find past glory in old markets, but customers shift to the new market and money is wasted.

When companies stop growing, it’s because markets shift. After markets shift, there isn’t any value left. And management efforts to defend the old success formula with investments in extensions simply fritter away investor money. That’s why they are really value traps. They are actually risky investments, because without growth there is little likelihood investors will ever see a higher stock price, and eventually they always collapse – it’s just a matter of when. Meanwhile, riding the swings up and down is best left for day traders – and you sure don’t want to be long the stock when the final downturn hits.

by Adam Hartung | May 3, 2011 | Current Affairs, Defend & Extend, In the Swamp, Leadership, Lock-in, Web/Tech

For the first time in 20 years, Apple’s quarterly profit exceeded Microsoft’s (see BusinessWeek.com “Microsoft’s Net Falls Below Apple As iPad Eats Into Sales.) Thus, on the face of things, the companies should be roughly equally valued. But they aren’t. This week Microsoft’s market capitalization is about $215B, while Apple’s is about $365B – about 70% higher. The difference is, of course, growth – and how a lack of it changes management!

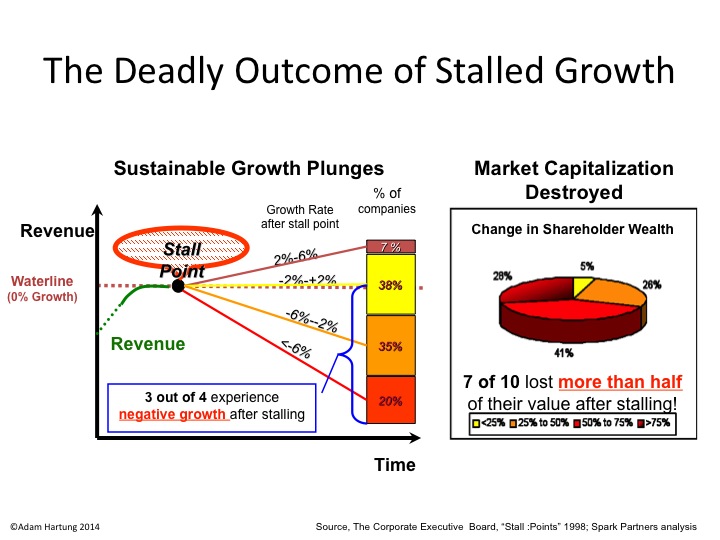

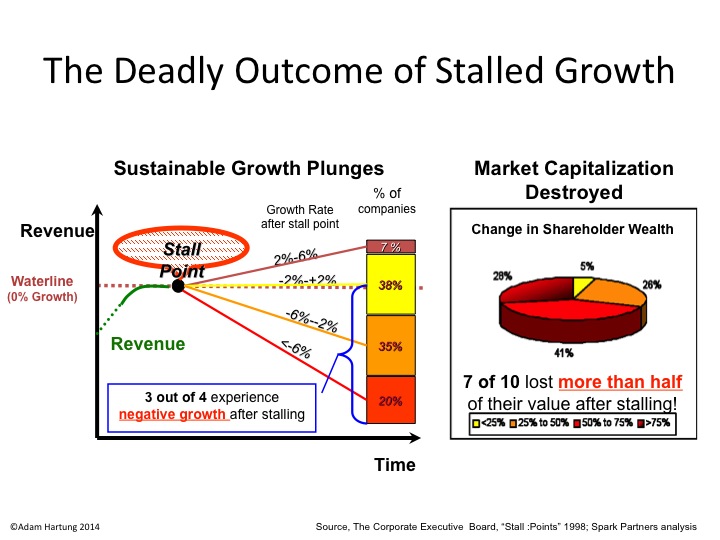

According to the Conference Board, growth stalls are deadly.

When companies hit a growth stall, 93% of the time they are unable to maintain even a 2% growth rate. 75% fall into a no growth, or declining revenue environment, and 70% of them will lose at least half their market capitalization. That’s because the market has shifted, and the business is no longer selling what customers really want.

At Microsoft, we see a company that has been completely unable to deal with the market shift toward smartphones and tablets:

- Consumer PC shipments dropped 8% last quarter

- Netbook sales plunged 40%

Quite simply, when revenues stall earnings become meaningless. Even though Microsoft earnings were up, it wasn’t because they are selling what customers really want to buy. In stalled companies, executives cut costs in sales, marketing, new product development and outsource like crazy in order to prop up earnings. They can outsource many functions. And they go to the reservoir of accounting rules to restate depreciation and expenses, delaying expenses while working to accelerate revenue recognition.

Stalled company management will tout earnings growth, even though revenues are flat or declining. But smart investors know this effort to “manufacture earnings” does not create long-term value. They want “real” earnings created by selling products customers desire; that create incremental, new demand. Success doesn’t come from wringing a few coins out of a declining market – but rather from being in markets where people prefer the new solutions.

Mobile phone sales increased 20% (according to IDC), and Apple achieved 14% market share – #3 – in USA (according to MediaPost.com) last quarter. And in this business, Apple is taking the lion’s share of the profits:

Image provided by BusinessInsider.com

When companies are growing, investors like that they pump earnings (and cash) back into growth opportunities. Investors benefit because their value compounds. In a stalled company investors would be better off if the company paid out all their earnings in dividends – so investors could invest in the growth markets.

But, of course, stalled companies like Microsoft and Research in Motion, don’t do that. Because they spend their cash trying to defend the old business. Trying to fight off the market shift. At Microsoft, money is poured into trying to protect the PC business, even as the trend to new solutions is obvious. Microsoft spent 8 times as much on R&D in 2009 as Apple – and all investors received was updates to the old operating system and office automation products. That generated almost no incremental demand. While revenue is stalling, costs are rising.

At Gurufocus.com the argument is made “Microsoft Q3 2011: Priced for Failure“. Author Alex Morris contends that because Microsoft is unlikely to fail this year, it is underpriced. Actually, all we need to know is that Microsoft is unlikely to grow. Its cost to defend the old business is too high in the face of market shifts, and the money being spent to defend Microsoft will not go to investors – will not yield a positive rate of return – so investors are smart to get out now!

Additionally, Microsoft’s cost to extend its business into other markets where it enters far too late is wildly unprofitable. Take for example search and other on-line products:

Chart source BusinessInsider.com