by Adam Hartung | Nov 22, 2013 | Current Affairs, Defend & Extend, In the Whirlpool, Leadership, Television

Do you really think in 2020 you’ll watch television the way people did in the 1960s? I would doubt it.

In today’s world if you want entertainment you have a plethora of ways to download or live stream exactly what you want, when you want, from companies like Netflix, Hulu, Pandora, Spotify, Streamhunter, Viewster and TVWeb. Why would you even want someone else to program you entertainment if you can get it yourself?

Additionally, we increasingly live in a world unaccepting of one-way communication. We want to not only receive what entertains us, but share it with others, comment on it and give real-time feedback. The days when we willingly accepted having information thrust at us are quickly dissipating as we demand interactivity with what comes across our screen – regardless of size.

These 2 big trends (what I want, when I want; and 2-way over 1-way) have already changed the way we accept entertaining. We use USB drives and smartphones to provide static information. DVDs are nearly obsolete. And we demand 24×7 mobile for everything dynamic.

Yet, the CEO of Charter Cable company wass surprised to learn that the growth in cable-only customers is greater than the growth of video customers. Really?

It was about 3 years ago when my college son said he needed broadband access to his apartment, but he didn’t want any TV. He commented that he and his 3 roommates didn’t have any televisions any more. They watched entertainment and gamed on screens around his apartment connected to various devices. He never watched live TV. Instead they downloaded their favorite programs to watch between (or along with) gaming sessions, picked up the news from live web sites (more current and accurate he said) and for sports they either bought live streams or went to a local bar.

To save money he contacted Comcast and said he wanted the premier internet broadband service. Even business-level service. But he didn’t want TV. Comcast told him it was impossible. If he wanted internet he had to buy TV. “That’s really, really stupid” was the way he explained it to me. “Why do I have to buy something I don’t want at all to get what I really, really want?”

Then, last year, I helped a friend move. As a favor I volunteered to return her cable box to Comcast, since there was a facility near my home. I dreaded my volunteerism when I arrived at Comcast, because there were about 30 people in line. But, I was committed, so I waited.

The next half-hour was amazingly instructive. One after another people walked up to the window and said they were having problems paying their bills, or that they had trouble with their devices, or wanted a change in service. And one after the other they said “I don’t really want TV, just internet, so how cheaply can I get it?”

These were not busy college students, or sophisticated managers. These were every day people, most of whom were having some sort of trouble coming up with the monthly money for their Comcast bill. They didn’t mind handing back the cable box with TV service, but they were loath to give up broadband internet access.

Again and again I listened as the patient Comcast people explained that internet-only service was not available in Chicagoland. People had to buy a TV package to obtain broad-band internet. It was force-feeding a product people really didn’t want. Sort of like making them buy an entree in order to buy desert.

As I retold this story my friends told me several stories about people who banned together in apartments to buy one Comcast service. They would buy a high-powered router, maybe with sub-routers, and spread that signal across several apartments. Sometimes this was done in dense housing divisions and condos. These folks cut the cost for internet to a fraction of what Comcast charged, and were happy to live without “TV.”

But that is just the beginning of the market shift which will likely gut cable companies. These customers will eventually hunt down internet service from an alternative supplier, like the old phone company or AT&T. Some will give up on old screens, and just use their mobile device, abandoning large monitors. Some will power entertainment to their larger screens (or speakers) by mobile bluetooth, or by turning their mobile device into a “hotspot.”

And, eventually, we will all have wireless for free – or nearly so. Google has started running fiber cable in cities including Austin, TX, Kansas City, MO and Provo, Utah. Anyone who doesn’t see this becoming city-wide wireless has their eyes very tightly closed. From Albuquerque, NM to Ponca City, OK to Mountain View, CA (courtesy of Google) cities already have free city-wide wireless broadband. And bigger cities like Los Angeles and Chicago are trying to set up free wireless infrastructure.

And if the USA ever invests in another big “public works infrastructure” program will it be to rebuild the old bridges and roads? Or is it inevitable that someone will push through a national bill to connect everyone wirelessly – like we did to build highways and the first broadcast TV.

So, what will Charter and Comcast sell customers then?

It is very, very easy today to end up with a $300/month bill from a major cable provider. Install 3 HD (high definition) sets in your home, buy into the premium movie packages, perhaps one sports network and high speed internet and before you know it you’ve agreed to spend more on cable service than you do on home insurance. Or your car payment. Once customers have the ability to bypass that “cable cost” the incentive is already intensive to “cut the cord” and set that supplier free.

Yet, the cable companies really don’t seem to see it. They remain unimpressed at how much customers dislike their service. And respond very slowly despite how much customers complain about slow internet speeds. And even worse, customer incredulous outcries when the cable company slows down access (or cuts it) to streaming entertainment or video downloads are left unheeded.

Cable companies say the problem is “content.” So they want better “programming.” And Comcast has gone so far as to buy NBC/Universal so they can spend a LOT more money on programming. Even as advertising dollars are dropping faster than the market share of old-fashioned broadcast channels.

Blaming content flies in the face of the major trends. There is no shortage of content today. We can find all the content we want globally, from millions of web sites. For entertainment we have thousands of options, from shows and movies we can buy to what is for free (don’t forget the hours of fun on YouTube!)

It’s not “quality programming” which cable needs. That just reflects industry deafness to the roar of a market shift. In short order, cable companies will lack a reason to exist. Like land-line phones, Philco radios and those old TV antennas outside, there simply won’t be a need for cable boxes in your home.

Too often business leaders become deaf to big trends. They are so busy executing on an old success formula, looking for reasons to defend & extend it, that they fail to evaluate its relevancy. Rather than listen to market shifts, and embrace the need for change, they turn a deaf ear and keep doing what they’ve always done – a little better, with a little more of the same product (do you really want 650 cable channels?,) perhaps a little faster and always seeking a way to do it cheaper – even if the monthly bill somehow keeps going up.

But execution makes no difference when you’re basic value proposition becomes obsolete. And that’s how companies end up like Kodak, Smith-Corona, Blackberry, Hostess, Continental Bus Lines and pretty soon Charter and Comcast.

by Adam Hartung | Nov 6, 2013 | Defend & Extend, Innovation, Leadership, Web/Tech

Can you believe it has been only 12 years since Apple introduced the iPod? Since then Apple’s value has risen from about $11 (January, 2001) to over $500 (today) – an astounding 45X increase.

With all that success it is easy to forget that it was not a “gimme” that the iPod would succeed. At that time Sony dominated the personal music world with its Walkman hardware products and massive distribution through consumer electronics chains such as Best Buy, and broad-line retailers like Wal-Mart. Additionally, Sony had its own CD label, from its acquisition of Columbia Records (renamed CBS Records,) producing music. Sony’s leadership looked impenetrable.

But, despite all the data pointing to Sony’s inevitable long-term domination, Apple launched the iPod. Derided as lacking CD quality, due to MP3’s compression algorithms, industry leaders felt that nobody wanted MP3 products. Sony said it tried MP3, but customers didn’t want it.

All the iPod had going for it was a trend. Millions of people had downloaded MP3 songs from Napster. Napster was illegal, and users knew it. Some heavy users were even prosecuted. But, worse, the site was riddled with viruses creating havoc with all users as they downloaded hundreds of millions of songs.

Eventually Napster was closed by the government for widespread copyright infreingement. Sony, et.al., felt the threat of low-priced MP3 music was gone, as people would keep buying $20 CDs. But Apple’s new iPod provided mobility in a way that was previously unattainable. Combined with legal downloads, including the emerging Apple Store, meant people could buy music at lower prices, buy only what they wanted and literally listen to it anywhere, remarkably conveniently.

The forecasted “numbers” did not predict Apple’s iPod success. If anything, good analysis led experts to expect the iPod to be a limited success, or possibly failure. (Interestingly, all predictions by experts such as IDC and Gartner for iPhone and iPad sales dramatically underestimated their success, as well – more later.) It was leadership at Apple (led by the returned Steve Jobs) that recognized the trend toward mobility was more important than historical sales analysis, and the new product would not only sell well but change the game on historical leaders.

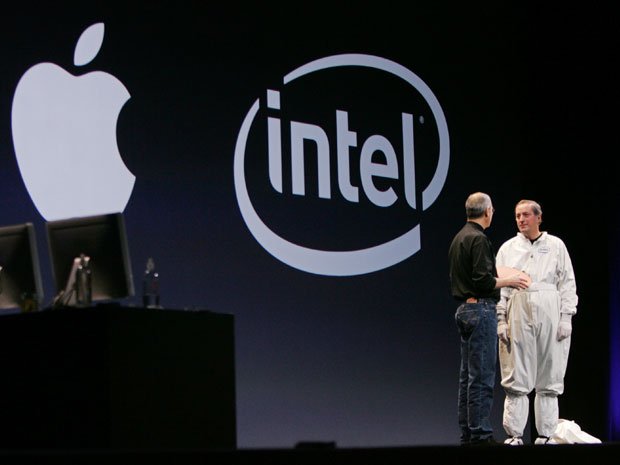

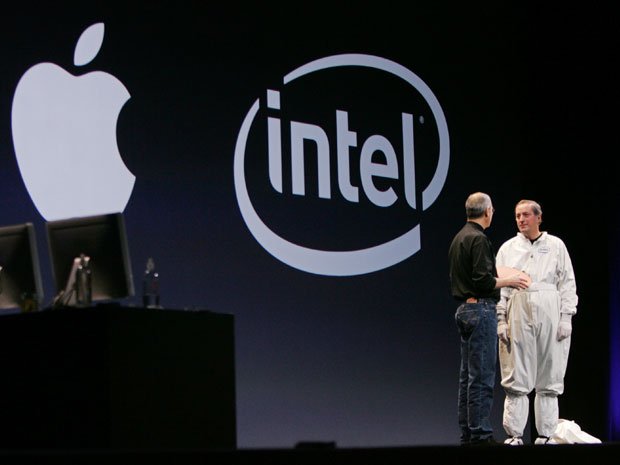

Which takes us to the mistake Intel made by focusing on “the numbers” when given the opportunity to build chips for the iPhone. Intel was a very successful company, making key components for all Microsoft PCs (the famous WinTel [for Windows+Intel] platform) as well as the Macintosh. So when Apple asked Intel to make new processors for its mobile iPhone, Intel’s leaders looked at the history of what it cost to make chips, and the most likely future volumes. When told Apple’s price target, Intel’s leaders decided they would pass. “The numbers” said it didn’t make sense.

Uh oh. The cost and volume estimates were wrong. Intel made its assessments expecting PCs to remain strong indefinitely, and its costs and prices to remain consistent based on historical trends. Intel used hard, engineering and MBA-style analysis to build forecasts based on models of the past. Intel’s leaders did not anticipate that the new mobile trend, which had decimated Sony’s profits in music as the iPod took off, would have the same impact on future sales of new phones (and eventually tablets) running very thin apps.

Harvard innovation guru Clayton Christensen tells audiences that we have complete knowledge about the past. And absolutely no knowledge about the future. Those who love numbers and analysis can wallow in reams and reams of historical information. Today we love the “Big Data” movement which uses the world’s most powerful computers to rip through unbelievable quantities of historical data to look for links in an effort to more accurately predict the future. We take comfort in thinking the future will look like the past, and if we just study the past hard enough we can have a very predictible future.

But that isn’t the way the business world works. Business markets are incredibly dynamic, subject to multiple variables all changing simultaneously. Chaos Theory lecturers love telling us how a butterfly flapping its wings in China can cause severe thunderstorms in America’s midwest. In business, small trends can suddenly blossom, becoming major trends; trends which are easily missed, or overlooked, possibly as “rounding errors” by planners fixated on past markets and historical trends.

Markets shift – and do so much, much faster than we anticipate. Old winners can drop remarkably fast, while new competitors that adopt the trends become “game changers” that capture the market growth.

In 2000 Apple was the “Mac” company. Pretty much a one-product company in a niche market. And Apple could easily have kept trying to defend & extend that niche, with ever more problems as Wintel products improved.

But by understanding the emerging mobility trend leadership changed Apple’s investment portfolio to capture the new trend. First was the iPod, a product wholly outside the “core strengths” of Apple and requiring new engineering, new distribution and new branding. And a product few people wanted, and industry leaders rejected.

Then Apple’s leaders showed this talent again, by launching the iPhone in a market where it had no history, and was dominated by Motorola and RIMM/BlackBerry. Where, again, analysts and industry leaders felt the product was unlikely to succeed because it lacked a keyboard interface, was priced too high and had no “enterprise” resources. The incumbents focused on their past success to predict the future, rather than understanding trends and how they can change a market.

Too bad for Intel. And Blackberry, which this week failed in its effort to sell itself, and once again changed CEOs as the stock hit new lows.

Then Apple did it again. Years after Microsoft attempted to launch a tablet, and gave up, Apple built on the mobility trend to launch the iPad. Analysts again said the product would have limited acceptance. Looking at history, market leaders claimed the iPad was a product lacking usability due to insufficient office productivity software and enterprise integration. The numbers just did not support the notion of investing in a tablet.

Anyone can analyze numbers. And today, we have more numbers than ever. But, numbers analysis without insight can be devastating. Understanding the past, in grave detail, and with insight as to what used to work, can lead to incredibly bad decisions. Because what really matters is vision. Vision to understand how trends – even small trends – can make an enormous difference leading to major market shifts — often before there is much, if any, data.

by Adam Hartung | Oct 23, 2013 | Current Affairs, Defend & Extend, Food and Drink, Leadership, Lifecycle

On 11 October Safeway announced it was going to either sell or close its 79 Dominick's brand grocery stores in Chicago. After 80 years in Chicago, San Francisco based Safeway leadership felt it was simply time for Dominick's to call it quits.

The grocery industry is truly global, because everyone eats and almost nobody grows their own food. It moves like a giant crude oil carrier, much slower than technology, so identifying trends takes more patience than, say, monitoring annual smartphone cycles. Yet, there are clearly pronounced trends which make a huge difference in performance.

Good for those who recognize them. Bad for those who don't.

Safeway, like a lot of the dominant grocers from the 1970s-1990s, clearly missed the trends.

Coming out of WWII large grocers replaced independent neighborhood corner grocers by partnering with emerging consumer goods giants (Kraft, P&G, Coke, etc.) to bring customers an enormous range of products very efficiently. They offered a larger selection at lower prices. Even though margins were under 10% (think 2% often) volume helped these new grocery chains make good returns on their assets. Dillon's (originally of Hutchinson, Kansas and later purchased by Kroger) became a 1970s textbook, case study model of effective financial management for superior returns by Harvard Business School guru William Fruhan.

But times changed.

Looking at the trend toward low prices, Aldi from Germany came to the U.S. market with a strategy that defines the ultimate in low cost. Often there is only one brand of any product in the store, and that is likely to be the chain's private label. And often it is only available in one size. And customers must be ready to use a quarter to borrow the shopping cart (returned if you replace the cart.) And customers pay for their sacks. Stores are remarkably small and efficient, frequently with only 2 or 3 employees. And with execution so well done that the Aldi brand became #1 in "simple brands" according to a study by brand consultancy Seigal+Gale.

Of course, we also know that big discount chains like WalMart and Target started cherry picking the traditional grocer's enormous SKU (stock keeping units) list, limiting selection but offering lower prices due to lower cost.

Looking at the quality trend, Whole Foods and its brethren demonstrated that people would pay more for better perceived quality. Even though filling the aisles with organic

products and the ultimate in freshness led to higher prices, and someone nicknaming the chain

"whole paycheck," customers payed up to shop there, leading to superior

returns.

Connected to quality has been the trend, which began 30 years ago, to "artisanal" products. Shoppers pay more to buy what are considered limited edition products that are perceived as superior due to a range of "artisanal quality" features; from ingredients used to age of product (or "freshness,") location of manufacture ("local,") extent to which it is considered "organic," quantity of added ingredients for preservation or vitamin enhancement ("less is more,") ecological friendliness of packaging and even producer policies regarding corporate social and ecological responsibility.

But after decades of partnership, traditional grocers today remain dependant on large consumer goods companies to survive. Large CPGs supply a massive number of SKUs in a limited number of contracts, making life easy for grocery store buyers. Big CPGs pay grocers for shelf space, coupons to promote customer purchases, rebates, ads in local store circulars, discounts for local market promotions, sales volumes exceeding commitments and even planograms which instruct employees how to place products on shelves — all saving money for the traditional grocer. In some cases payments and rebates equalling more than total grocer profits.

Additionally, in some cases big CPG firms even deliver their products into the store and stock shelves at no charge to the grocer (called store-door-delivery as a substitute for grocer warehouse and distribution.) And the big CPG firms spend billions of dollars on product advertising to seemingly assure sales for the traditional grocer.

These practices emerged to support the bi-directionally beneficial historically which tied the traditional grocer to the large CPG companies. For decades they made money for both the CPG suppliers and their distributors. Customers were happy.

But the market shifted, and Safeway (including its employees, customers, suppliers and investors) is the loser.

The old retail adage "location, location, location" is no longer enough in grocery. Traditional grocery stores can be located next to good neighborhoods, and execute that old business model really well, and, unfortunately, not make any money. New trends gutted the old Safeway/Dominick's business model (and most of the other traditional grocers) even though that model was based on decades of successful history.

The trend to low price for customers with the least funds led them to shop at the new low-price leaders. And companies that followed this trend, like Aldi, WalMart and Target are the winners.

The trend to higher perceived quality and artisanal products led other customers to retailers offering a different range of products. In Chicago the winners include fast growing Whole Foods, but additionally the highly successful Marianno's division of Roundy's (out of Milwaukee.) And even some independents have become astutely profitable competitors. Such as Joe Caputo & Sons, with only 3 stores in suburban Chicago, which packs its parking lots daily by offering products appealing to these trendy shoppers.

And then there's the Trader Joe's brand. Instead of being all things to all people, Aldi created a new store chain designed to appeal to customers desiring upscale products, and named it Trader Joe's. It bares scance resemblance to an Aldi store. Because it is focused on the other trend toward artisinal and quality. And it too brings in more customers, at higher margin, than Dominick's.

When you miss a trend, it is very, very painful. Even if your model worked for 75 years, and is tightly linked to other giant corporations, new trends lead to market shifts making your old success formula obsolete.

Simultaneously, new trends create opportunities. Even in enormous industries with historically razor-thin margins – or even losses. Building on trends allows even small start-up companies to compete, and make good profits, in cutthroat industries – like groceries.

Trends really matter. Leaders who ignore the trends will have companies that suffer. Meanwhile, leaders who identify and build on trends become the new winners.

by Adam Hartung | Oct 9, 2013 | Current Affairs, In the Rapids, Innovation, Lifecycle

In 1985 there was universal agreement that investors should

be heavily in pharmaceuticals.

Companies like Merck, Eli Lilly, Pfizer, Sanofi, Roche, Glaxo and Abbott

were touted as the surest route to high portfolio returns.

Today, not so much.

Merck, once a leader in antibiotics, is laying off 20% of

its staff. Half in R&D; the

lifeblood of future products and profits.

Lilly is undertaking

another round of 2013 cost cuts. Over

the last year about 100,000 jobs have been eliminated in big pharma companies,

which have implemented spin-outs and split-ups as well as RIFs.

What happened? In the old days pharma companies had to demonstrate

their drug worked; called product efficacy. It did not have to be better than existing drugs. If the drug worked, without big safety

issues, the company could launch it.

Then the business folks took over with ads, distribution,

salespeople and convention booths, convincing doctors to prescribe and us to

buy.

Big pharma companies grew into large, masterful consumer

products companies. Leadership’s view of the market changed, as it was

perceived safer to invest in Pepsi vs. Coke marketing tactics and sales warfare

to dominate a blockbuster category than product development. Think of the marketing cost in the

Celebrex vs. Vioxx war. Or Viagra

vs. Cialis.

But the market shifted when the FDA decided new drugs had to

be not only efficacious, they had to enhance the standard of care. New drugs actually had to prove better in clinical trials than existing

drugs. And often safer, too.

Hurrumph. Big pharma’s enormous scale advantages in

marketing and communication weren’t enough to assure new product success. It actually took new products. But that meant bigger R&D investments,

perceived as more risky, than the new consumer-oriented pharma companies could

tolerate. Shortly pipelines

thinned, generics emerged and much lower margins ensued.

In some disease areas, this evolution was disastrous for

patients. In antibiotics,

development of new drugs had halted.

Doctors repeatedly prescribed (some say overprescribed) the same antibiotics. As the bacteria evolved, infections

became more difficult to treat.

With no new antibiotics on the market the risk of death from

bacterial infections grew, leading to a national public health crisis. According to the Centers for Disease

Control (CDC) there are over 2 million cases of antibiotic resistant infections

annually. Today just one type of

resistant “staph infection,” known as MRSA, kills more people in the USA than

HIV/AIDs – killing more people every year than polio did at its peak. The most

difficult to treat pathogens (called ESKAPE) are the cause of 66% of hospital

infections.

And that led to an important market shift – via regulation

(Congress?!?!)

With help from the CDC and NIH, the Infectious Diseases

Society of America pushed through the GAIN (Generating Antibiotic Incentives

Now) Act (H.R. 2182.) This gave

creators of new antibiotics the opportunity for new, faster pathways through

clinical trials and review in order to expedite approvals and market launch.

Additionally new product market exclusivity was lengthened an additional 5

years (beyond the normal 5 years) to enhance investor returns.

Which allowed new game changers like Melinta Therapeutics

into the game.

Melinta (formerly Rib-X) was once considered a “biopharma science

company” with Nobel Prize-winning technology, but little hope of commercial

product launch. But now the large

unmet need is far clearer, the playing field has few to no large company

competitors, the commercialization process has been shortened and cheapened,

and the opportunity for extended returns is greater!

Venture firm Vatera Healthcare Partners, with a history of investing in game changers (especially transformational technology,) entered the picture as lead investor. Vatera's founder Michael Jaharis quickly hired Mary Szela, the former head of U.S.

Pharmaceuticals for Abbott (now Abbvie) as CEO. Her resume includes leading the growth of Humira, one of

the world’s largest pharma brands with multi-billion dollar annual sales.

Under her guidance Melinta has taken fast action to work

with the FDA on a much quicker clinical trials pathway of under 18 months for

commercializing delafloxacin. In layman’s

language, early trials of delafloxacin appeared to provide better performance

for a broad spectrum of resistant bacteria in skin infections. And as a one-dose oral (or IV)

application it could be a simpler, high quality solution for gonorrhea.

Melinta continues adding key management resources as it

seeks “breakthrough product” designation under GAIN from the FDA for its RX-04

product. RX-04 is an entirely

different scientific approach to infectious disease control, based on that previously

mentioned proprietary, Nobel-winning ribosome science. It’s a potential product category

game changer that could open the door for a pipeline of follow-on products.

Melinta is using GAIN to do something big pharma, with its

shrinking R&D and commercial staff, is unable to accomplish. Melinta is helping

redefine the rules for approving antibiotics, in order to push through new,

life-saving products.

The best news is that this game change is great for investors.

Those companies who understand the

trend (in this case, the urgent need for new antibiotics) and how the market

has shifted (GAIN,) are putting in place teams to leverage newly invented drugs

working with the FDA. Investment timelines and dollars are looking

far more manageable – and less risky.

Twenty-five years ago pharma looked like a big-company-only

market with little competition and huge returns for a handful of companies. But things changed. Now companies (like Melinta) with new

solutions have the opportunity to move much faster to prove efficacy and safety

– and save lives. They are the

game changers, and the ones more likely to provide not only solutions to the

market but high investor returns.

by Adam Hartung | Sep 30, 2013 | Current Affairs, Defend & Extend, Leadership, Lock-in

Last week we learned that there is no doubt, the world is warming. A U.N. report affirmed by some 1,000 scientists asserted 95% confidence as to the likely outcomes, as well as the cause. We must expect more volatility in weather, and that the oceans will continue rising.

Yet, most people really could have cared less. And a vocal minority still clings to the notion that because the prior decade saw a slower heating, perhaps this will all just go away.

Incredibly, for those of us who don't live and work in Florida, there was CNN news footage of daily flooding in Miami's streets due to current sea levels which have risen over last 50 years. Given that we can now predict the oceans will rise between 1 and 6 feet in the next 50 years, it is possible to map the large areas of Miami streets which are certain to be flooded.

There is just no escaping the fact that the long-term trend of global warming will have a remarkable impact on everyone. It will affect transportation, living locations, working locations, electricity generation and distribution, agriculture production, textile production – everything will be affected. And because it is happening so slowly, we actually can do lots of modeling about what will happen.

Yet, I never hear any business leaders talk about how they are planning for global warning. No comments about how they are making changes to keep their business successful. Nor comments about the new opportunities this will create. Even though the long-term impacts will be substantial, the weather and how it affects us is treated like the status quo.

What does this have in common with the government shutdown?

America has known for decades that its healthcare system was dysfunctional; to be polite. It was incredibly expensive (by all standards) and yet had no better outcomes for citizens than other modern countries. For over 20 years efforts were attempted to restructure health care. Yet as the morass of regulations ballooned, there was no effective overhaul that addressed basic problems built into the system. Costs continued to soar, and more people joined the ranks of those without health care, while other families were bankrupted by illness.

Finally, amidst enormous debate, the Affordable Care Act was passed. Despite wide ranging opinions from medical doctors, nurses, hospital and clinic administrators, patient advocacy groups, pharmaceutical companies, medical device companies and insurance companies (to name just some of those with a vested interest and loud, competing, viewpoints) Congress passed the Affordable Care Act which the President signed.

Like most such things in America, almost nobody was happy. No one got what they wanted. It was one of those enormous, uniquely American, compromises. So, like unhappy people do in America, we sued! And it took a few years before finally the Supreme Court ruled that the legislation was constitutional. The Affordable Care Act would be law.

But, people remain who simply do not want to accept the need for health care change. So, in a last ditch effort to preserve the status quo, they are basically trying to kidnap the government budget process and hold it hostage until they get their way. They have no alternative plan to replace the Affordable Care Act. They simply want to stop it from moving forward.

What global warming and the government shut down have in common are:

- Very long-term problems

- No quick solution for the problem

- No easy solution for the problem

- If you do nothing about the problem today, you have no immediate calamity

- Doing anything about the problem affects almost everyone

- Doing anything causes serious change

So, in both cases, people have emerged as the Status Quo Police. They take on the role of stopping change. They will do pretty much anything to defend & extend the status quo:

- Ignore data that is contradictory to the best analytical views

- Claim that small probability outcomes (that change may not be necessary) justifies doing nothing

- Delay, delay, delay taking any action until a disaster requires action

- Constantly claim that the cost of change is not justified

- Claim that the short-term impact of change is more deleterious than the long-term benefits

- Assume that the status quo will somehow resolve itself favorably – with no supporting evidence or analysis

- Undertake any action that preserves the status quo

- Threaten a "scorched earth policy" (that they will create big, immediate problems if forced to change the status quo)

The earth is going to become warmer. The oceans will rise, and other changes will happen. If you don't incorporate this in your plans, and take action, you can expect this trend will harm you.

U.S. health care is going to be reformed. How it will happen is just starting. How it will evolve is still unclear. Those who create various scenarios in their plans to prepare for this change will benefit. Those who do nothing, hoping it goes away, will find themselves struggling.

The Status Quo Police, trying their best to encourage people to ignore the need for change – the major, important trends – are helping nobody. By trying to preserve the status quo they inhibit effective planning, and action, to prepare for a different (better) future.

Does your organization have Status Quo Police? Are their functions, groups or individuals who are driven to defend and extend the status quo – even in the face of trends that demonstrate change is necessary? Can they stop conversations around substantial change? Are they allowed to stop future planning for scenarios that are very different from the past? Can they enforce cultural norms that stop considering new alternatives? Can they control resources resulting in less innovation and change?

Let's learn from these 2 big issues. Change is inevitable. It is even necessary. Trying to preserve the status quo is costly, and inhibits taking long-term effective action. Status Quo Police are obstructionists who keep us from facing, and solving, difficult problems. They don't help our organizations create a new, more successful future. Only by overcoming them can we reach our full potential, and create opportunities out of change.

by Adam Hartung | Sep 19, 2013 | Current Affairs, In the Swamp, Innovation, Leadership, Television, Web/Tech

Apple announced the new iPhones recently. And mostly, nobody cared.

Remember when users waited anxiously for new products from Apple? Even the media became addicted to a new round of Apple products every few months. Apple announcements seemed a sure-fire way to excite folks with new possibilities for getting things done in a fast changing world.

But the new iPhones, and the underlying new iPhone software called iOS7, has almost nobody excited.

Instead of the product launches speaking for themselves, the CEO (Tim Cook) and his top product development lieutenants (Jony Ive and Craig Federighi) have been making the media rounds at BloombergBusinessWeek and USAToday telling us that Apple is still a really innovative place. Unfortunately, their words aren't that convincing. Not nearly as convincing as former product launches.

CEO Cook is trying to convince us that Apple's big loss of market share should not be troubling. iPhone owners still use their smartphones more than Android owners, and that's all we should care about. Unfortunately, Apple profits come from unit sales (and app sales) rather than minutes used. So the chronic share loss is quite concerning.

Especially since unit sales are now growing barely in single digits, and revenue growth quarter-over-quarter, which sailed through 2012 in the 50-75% range, have suddenly gone completely flat (less than 1% last quarter.) And margins have plunged from nearly 50% to about 35% – more like 2009 (and briefly in 2010) than what investors had grown accustomed to during Apple's great value rise. The numbers do not align with executive optimism.

For industry aficianados iOS7 is a big deal. Forbes Haydn Shaughnessy does a great job of laying out why Apple will benefit from giving its ecosystem of suppliers a new operating system on which to build enhanced features and functionality. Such product updates will keep many developers writing for the iOS devices, and keep the battle tight with Samsung and others using Google's Android OS while making it ever more difficult for Microsoft to gain Windows8 traction in mobile.

And that is good for Apple. It insures ongoing sales, and ongoing profits. In the slog-through-the-tech-trench-warfare Apple is continuing to bring new guns to the battle, making sure it doesn't get blown up.

But that isn't why Apple became the most valuable publicly traded company in America.

We became addicted to a company that brought us things which were great, even when we didn't know we wanted them – much less think we needed them. We were happy with CDs and Walkmen until we discovered much smaller, lighter iPods and 99cent iTunes. We were happy with our Blackberries until we learned the great benefits of apps, and all the things we could do with a simple smartphone. We were happy working on laptops until we discovered smaller, lighter tablets could accomplish almost everything we couldn't do on our iPhone, while keeping us 24×7 connected to the cloud (that we didn't even know or care about before,) allowing us to leave the laptop at the office.

Now we hear about upgrades. A better operating system (sort of sounds like Microsoft talking, to be honest.) Great for hard core techies, but what do users care? A better Siri; which we aren't yet sure we really like, or trust. A new fingerprint reader which may be better security, but leaves us wondering if it will have Siri-like problems actually working. New cheaper color cases – which don't matter at all unless you are trying to downgrade your product (sounds sort of like P&G trying to convince us that cheaper, less good "Basic" Bounty was an innovation.)

More (upgrades) Better (voice interface, camera capability, security) and Cheaper (plastic cases) is not innovation. It is defending and extending your past success. There's nothing wrong with that, but it doesn't excite us. And it doesn't make your brand something people can't live without. And, while it keeps the battle for sales going, it doesn't grow your margin, or dramatically grow your sales (it has declining marginal returns, in fact.)

And it won't get your stock price from $450-$475/share back to $700.

We all know what we want from Apple. We long for the days when the old CEO would have said "You like Google Glass? Look at this……. This will change the way you work forever!!"

We've been waiting for an Apple TV that let's us bypass clunky remote controls, rapidly find favorite shows and helps us avoid unwanted ads and clutter. But we've been getting a tease of Dick Tracy-esque smart watches.

From the world's #1 tech brand (in market cap – and probably user opinion) we want something disruptive! Something that changes the game on old companies we less than love like Comcast and DirecTV. Something that helps us get rid of annoying problems like expensive and bad electric service, or routers in our basements and bedrooms, or navigation devices in our cars, or thumb drives hooked up to our flat screen TVs —- or doctor visits. We want something Game Changing!

Apple's new CEO seems to be great at the Sustaining Innovation game. And that pretty much assures Apple of at least a few more years of nicely profitable sales. But it won't keep Apple on top of the tech, or market cap, heap. For that Apple needs to bring the market something big. We've waited 2 years, which is an eternity in tech and financial markets. If something doesn't happen soon, Apple investors deserve to be worried, and wary.

by Adam Hartung | Sep 12, 2013 | General, In the Whirlpool, Leadership

This week the people who decide what composes the Dow Jones Industrial Average booted off 3 companies and added 3 others. What's remarkable is how little most people cared!

"The Dow," as it is often called, is intended to represent the core of America's economy. "As the Dow goes, so goes America" is the theory. It is one of the most watched indices of all markets, with many people tracking how much it goes up, or down, every trading day. So being a component of the DJIA is a pretty big deal.

It's not a good day when you find out your company has been removed from the index. Because it is a very public statement that your company simply isn't all that important any more. Certainly not as important as it once was! Your relevance, once considered core to representing the economy, has dissipated. And, unfortunately, most companies that fall off the DJIA slip away into oblivion.

I have a simple test. Do like Jay Leno, of Tonight Show fame, and simply ask a dozen college graduates that are between 26 and 31 about a company. If they know that company, and are positively influenced by it, you have relevancy. If they don't care about that company then the CEO and Board should take note, because it is an early indicator that the company may well have lost relevancy and is probably in more trouble than the leaders want to admit.

Ask these folks about Alcoa (AA) and what do you imagine the typical response? "Alcoa?" It is a rare person under 40 who knows that Alcoa was once the king of aluminum — back when we wrapped food in "tin foil" and before we all drank sodas and beer from a can. To most, "Alcoa" is a random set of letters with no meaning – like Altria – rather than its origin as ALuminum COrporation of America.

But, its not even the largest aluminum company any more. Alcoa is now 3rd. In a world where we live on smartphones and tablets, who really cares about a mining company that deals in commodities? Especially the third largest with no growth prospects?

Speaking of smartphones, Hewlett Packard (HPQ) was recently considered a bellweather of the tech industry. An early innovator in test equipment, it was one of the original "Silicon Valley" companies. But its commitment to printers has left people caring little about the company's products, since everyone prints less and less as we read more and more off digital screens.

Past-CEO Fiorina's huge investment in PCs by buying Compaq (which previously bought minicomputer maker DEC,) committed the rest of HP into what is now one of the fastest shrinking markets. And in PCs, HP doesn't even have any technology roots. HP is just an assembler, mostly offshore, as its products are all based on outsourced chip and software technology.

What a few years ago was considered a leader in technology has become a company that the younger crowd identifies with technology products they rarely use, and never buy. And lacking any sort of exciting pipeline, nobody really cares about HP.

Bank of America (BAC) was one of the 2 leaders in financial services when it entered the DJIA. It was a powerhouse in all things banking. But, as the mortgage market disintegrated B of A rapidly fell into trouble. It's shotgun wedding with Merrill Lynch to save the investment bank from failure made the B of A bigger, but not stronger.

Now racked with concerns about any part of the institution having long-term success against larger, and better capitalized, banks in America and offshore has left B of A with a lot of branches, but no market leadership. What innovations B of A may have had in lending or derivatives are now considered headaches most people either don't understand, or largely despise.

These 3 companies were once great lions of their industries. And they were rewarded with placement on the DJIA as icons of the economy. But they now leave with a whimper. Their values so shredded that their departure makes almost no impact on calculating the DJIA using the remaining companies. (Note: the DJIA calculation was significantly impacted by the addition of much higher valued companies Nike, Goldman Sachs and Visa.)

If we look at some past examples of other companies removed from the DJIA, one should be skeptical about the long-term future for these three:

- 2009 – GM removed due to bankruptcy

- 2004 – AT&T and Kodak removed (both ended up in bankruptcy)

- 1999 – Goodyear, Union Carbide, Sears

- 1997 – Westinghouse, Woolworths

- 1991 – American Can, Navistar/International Harvester

Any company can lose relevancy. Markets shift. There is risk incurred by focusing on the status quo (Status Quo Risk.) New technology, regulations, competitors, business practices — innovations of all sorts — enter the market daily. Being really good at something, in fact being the worlds BEST at something, does not insure success or longevity (despite the popularity of In Search of Excellence).

When markets shift, and your company doesn't, you can find yourself without relevancy. And with a fast declining value. Whether you are iconic – or not.

by Adam Hartung | Sep 4, 2013 | Current Affairs, Defend & Extend, In the Whirlpool, Leadership, Lock-in, Web/Tech

Just over a week after Microsoft announces plans to replace CEO Steve Ballmer the company announced it will spend $7.2B to buy the Nokia phone/tablet business. For those looking forward to big changes at Microsoft this was like sticking a pin in the big party balloon!

Everyone knows that Microsoft's future is at risk now that PC sales are declining globally at nearly 10% – with developing markets shifting even faster to mobile devices than the USA. And Microsoft has been the perpetual loser in mobile devices; late to market and with a product that is not a game changer and has only 3% share in the USA.

But, despite this grim reality, Microsoft has doubled-down (that's doubled its bet for non-gamblers) on its Windows 8 OS strategy, and continues to play "bet the company". Nokia's global market share has shriveled to 15% (from 40%) since former Microsoft exec-turned-Nokia-CEO Stephen Elop committed the company to Windows 8. Because other Microsoft ecosystem companies like HP, Acer and HP have been slow to bring out Win 8 devices, Nokia has 90% of the miniscule market that is Win 8 phones. So this acquisition brings in-house a much deeper commitment to spending on an effort to defend & extend Microsoft's declining O/S products.

As I predicted in January, the #1 action we could expect from a Ballmer-led Microsoft is pouring more resources into fighting market leaders iOS and Android – an unwinnable war. Previously there was the $8.5B Skype and the $400M Nook, and now a $7.2B Nokia. And as 32,000 Nokia employees join Microsoft losses will surely continue to rise. While Microsoft has a lot of cash – spending it at this rate, it won't last long!

Some folks think this acquisition will make Microsoft more like Apple, because it now will have both hardware and software which in some ways is like Apple's iPhone. The hope is for Apple-like sales and margins soon. But, unfortunately, Google bought Motorola months ago and we've seen that such revenue and profit growth are much harder to achieve than simply making an acquisition. And Android products are much more popular than Win8. Simply combining Microsoft and Nokia does not change the fact that Win8 products are very late to market, and not very desirable.

Some have postulated that buying Nokia was a way to solve the Microsoft CEO succession question, positioning Mr. Elop for Mr. Ballmer's job. While that outcome does seem likely, it would be one of the most expensive recruiting efforts of all time. The only reason for Mr. Elop to be made Microsoft CEO is his historical company relationship, not performance. And that makes Mr. Elop is exactly the wrong person for the Microsoft CEO job!

In October, 2010 when Mr. Elop took over Nokia I pointed out that he was the wrong person for that job – and he would destroy Nokia by making it a "Microsoft shop" with a Microsoft strategy. Since then sales are down, profits have evaporated, shareholders are in revolt and the only good news has been selling the dying company to Microsoft! That's not exactly the best CEO legacy.

Mr. Elop's job today is to sell more Win8 mobile devices. Were he to be made Microsoft CEO it is likely he would continue to think that is his primary job – just as Mr. Ballmer has believed. Neither CEO has shown any ability to realize that the market has already shifted, that there are two leaders far, far in front with brand image, products, apps, developers, partners, distribution, market share, sales and profits. And it is impossible for Microsoft to now catch up.

It is for good reason that short-term traders pushed down Microsoft's share value after the acquisition was announced. It is clear that current CEO Ballmer and Microsoft's Board are still stuck fighting the last war. Still trying to resurrect the Windows and Office businesses to previous glory. Many market anallysts see this as the last great effort to make Ballmer's bet-the-company on Windows 8 pay off. But that's a bet which every month is showing longer and longer odds.

Microsoft is not dead. And Microsoft is not without the ability to turn around. But it won't happen unless the Board recognizes it needs to steer Microsoft in a vastly different direction, reduce (rather than increase) investments in Win8 (and its devices,) and create a vision for 2020 where Microsoft is highly relevant to customers. So far, we're seeing all the wrong moves.

by Adam Hartung | Aug 23, 2013 | In the Swamp, Leadership, Software, Web/Tech

Steve Ballmer announced he would be retiring as CEO of Microsoft within the next 12 months. This extended timing, rather than immediately, shows clear the Board is ready for him to go but there is nobody ready to replace him.

The big question is, who would want Ballmer's job? It will be very tough to make Microsoft an industry leader again. What would his replacement propose to do? The fuse for a turnaround is short, and the options faint.

Microsoft has been on a downhill trajectory for at least 4 years. Although the company has introduced innovations in gaming (xBox and Kinect) as well as on-line (games and Bing), those divisions perpetually lose money. Stiff competitors Sony, Nintendo and Google have made these forays intellectually interesting, but of no value for investors or customers. The end-game for Microsoft has remained Windows – and as PC sales decline that's very bad news.

Microsoft viability has been firmly tied to Windows and Office sales. Historically these have been unassailable products, creating over 100% of the profits at Microsoft (covering losses in other divisions.) But, these products have lost growth, and relevancy. Windows 8 and Office 365 are product nobody really cares about, while they keep looking for updates from Apple, Google, Amazon and Samsung.

The market started going mobile 10 years ago. As Apple and Google promoted increased mobility, Microsoft tried to defend & extend its PC stronghold. It was a classic business inflection point in the making. Everyone knew at some point mobile devices would be more important than PCs. But most industry insiders (including Microsoft) kept thinking it would be later rather than sooner.

They were wrong. The shift came a lot faster than expected. Like in sailboat racing, suddenly the wind was taken out of Microsoft's sails as competitors shot to the lead in customer interest. While people were excited for new smartphones and tablets, Microsoft tried to re-engineer its historical product as an extension into the new market.

Windows 8 tablets and Surface tablets were ill-fated from the beginning. They did not appeal to the huge installed base of Windows customers, because changes like touch screens and tiles simply were too expensive and too behaviorally different. And they offered no advantage for people to switch that had already started buying iOS and Android products. Not to mention an app availability about 10% of the market leaders. Simply put, investing in Windows 8 and its own tablet was like adding bricks to a downhill runaway truck (end-of-life for PCs) – it sped up the time to an inevitable crash.

And spending money on poorly thought out investments like the Barnes & Noble Nook merely demonstrated Microsoft had money to burn, rather than a strategy for competing. Skype cost some $8B, but how has that helped Microsoft become more competive? It's not just an overspending on internal projects that failed to achieve any market success, but a series of wasted investments in bad acquisitions that showed Microsoft had no idea how it was going to regain industry leadership in a changing marketplace going more mobile and into the cloud every month.

Now the situation is pretty dire, and now is the time for Microsoft to give up on its defend and extend strategy for Windows/Office. Customers are openly uninterested in new laptops running Windows 8. And Win 8.1 will not change this lackadaisical attitude. Nobody is interested in Windows 8 phones, or tablets. This has left companies in the Microsoft ecosystem like HP, Dell and Nokia gasping for air as sales tumble, profits evaporate and customers flock to new solutions from Apple and Samsung. Instead of seeking out an update to Office for a new PC, people are using much lighter (and cheaper) cloud services from Amazon and office solutions like Google docs. And most of those old add-on product sales, like printers and servers, are disappearing into the cloud and mobile displays.

So now, after being forced to write off Surface and report a horrible quarter, the Board has pushed Ballmer out the door. Pretty remarkable. But, incredibly late. Just like the leaders at RIM stayed too long, leaving the company with no future options as Blackberry sales plummeted, Ballmer is taking leave as sales, profits and cash flow are taking a turn for the worst. And only months after a reorganization that simply made the whole situation a lot more confusing for not only investors, but internal managers and employees.

Microsoft has a big cash hoard, but how long will that last? As its distribution system falters, and sales drop, the costs will rapidly catch up with cash flow. Big layoffs are a certainty; think half the workforce in 2 years. Equally certain are sales of divisions (who can buy xBox market share and turn it competitively profitable?) or shut-downs (how long will Bing stay alive when it is utterly unnecessary and expensive to maintain?)

But, there is a better option. Without the cash from

Windows/Office, you can't keep much of the rest of Microsoft walking. So

now is the time to cut investments in Windows/Office and put money into the

best things Microsoft has going – primarily Kinect and cloud services. A radical restructuring of its spending and investments.

Kinect is an incredible product. It has found multiple applications Microsoft fails to capitalize upon. Kinect has the possibility of becoming the centerpiece for managing how we connect to data, how we store data, how we find data. It can bring together our smartphone, tablet and historical laptop worlds – and possibly even connect this to traditional TV and radio. It can be the centerpiece for two-way communications (think telephone or skype via all your devices.) Coupled with the right hardware, it can leapfrog iTV (which we still are waiting to see) and Cisco simultaneously.

In cloud services it will take a lot to compete with leaders Amazon, IBM, Apple and Google. They have made big investments, and are far in front. But, this is the bread-and-butter market for Microsoft. Millions of small businesses that want easy to use BYOD (bring your own device) environment, and easy access to data, documents and functionality for IT, like guaranteed data back-up and uptime, and user functionality like all those apps. These customers have relied on Microsoft for these kind of services for years, and would enjoy a services provider with an off-the-shelf product they can implement easily and cheaply that supports all their needs. Expensive to develop, but a growing market where Microsoft has a chance to leapfrog competitors.

As for Bing, give it to Yahoo – if Marissa Mayer will take it. Stop the bloodletting and get out of a market where Microsoft has never succeeded. Bing is core to Yahoo's business. If you can trade for some Yahoo stock, go for it. Let Yahoo figure out how to sell content and ads, while Microsoft refocuses on the new platform for 2017; from the user to the infrastructure services.

Strong leaders have their benefits. But, when they don't understand market shifts, and spend far too long trying to defend & extend past markets, they can put their organizations in terrible jeopardy of total failure. Ballmer leaves no with clear replacement, nor with any vision in place for leapfrogging competitors and revitalizing Microsoft.

So it is imperative the new leader provide this kind of new thinking. There are trends developing that create future scenarios where Microsoft can once again be a market leader. And it will be the role of the new CEO to identify that vision and point Microsoft's investments in the right direction to regain viability by changing the game on the current winners.

by Adam Hartung | Aug 6, 2013 | Current Affairs, Defend & Extend, In the Swamp, Innovation, Leadership

Jeff Bezos, founder of Amazon worth $25.2B just paid $250 million to become sole owner of The Washington Post.

Some think the recent rash of of billionaires buying newspapers is simply rich folks buying themselves trophies. Probably true in some instances – and that benefits no one. Just look at how Sam Zell ruined The Chicago Tribune and Los Angeles Times. Or Rupert Murdoch's less than stellar performance owning The Wall Street Journal. It's hard to be excited about a financially astute commodities manager, like John Henry, buying The Boston Globe – as it has all the earmarks of someone simply jumping in where angels fear to tread.

These companies lost their way long ago. For decades they defined themselves as newspaper companies. They linked everything about what they did to printing a daily paper. The service they provided, which was a mix of hard news and entertainment reporting, was lost in the productization of that service into a print deliverable.

So when people started to look for news and entertainment on-line, these companies chose to ignore the trend. They continued to believe that readers would always want the product – the paper – rather than the service. And they allowed themselves to remain fixated on old processes and outdated business models long after the market shifted.

The leaders ignored the fact that advertisers could obtain much more directed placement at targets, at far lower cost, on-line than through the broad-based, general ads placed in newspapers. And that consumers could get a much faster, and cheaper, sale via eBay, CraigsList or Vehix.com than via overpriced classified ads.

Newspaper leadership kept trying to defend their "core" business of collecting news for daily publication in a paper format. They kept trying to defend their local advertising base. Even though every month more people abandoned them for an on-line format. Not one major newspaper headmast made a strong commitment to go on-line. None tried to be #1 in news dissemination via the web, or take a leadership role in associating ad placement with news and entertainment.

They could have addressed the market shift, and changed their approach and delivery. But they did not.

Money manager Mr. Henry has done a good job of turning the Boston Red Sox into a profitable institution. But there is nothing in common between the Red Sox, for which you can grow the fan base, bring people to the ballpark and sell viewing rights, and The Boston Globe. The former is unique. The latter is obsolete. Yes, the New York Times company paid $1.1B for the Globe in 1993, but that doesn't mean it's worth $70M today. Given its revenue and cost structure, as a newspaper it is probably worth nothing.

But, we all still want news. Nobody wants the information infrastructure collecting what we need to know to crumble. Nobody wants journalism to die. But it is unreasonable to expect business people to keep investing in newspapers just to fulfill a public good. Even Mr. Zell abandoned that idea.

Thus, we need the news, as a service, to be transformed into a new, profitable enterprise. Somehow these organizations have to abandon the old ways of doing things, including print and paper distribution, and transform to meet modern needs. The 6 year revenue slide at Washington Post has to stop, and instead of thinking about survival company leadership needs to focus on how to thrive with a new, profitable business model.

And that's why we all should be glad Jeff Bezos bought The Washington Post. As head of Amazon.com The Harvard Business Review ranked him the second best performing CEO of the last decade. CNNMoney.com named him Business Person of the Year 2012, and called him "the ultimate disruptor."

By not doing what everyone else did, breaking all the rules of traditional retail, Mr. Bezos built Amazon.com into a $61B general merchandise retailer in 20 years. When publishers refused to create electronic books he led Amazon into competing with its suppliers by becoming a publisher. When Microsoft wouldn't produce an e-reader, retailer and publisher Amazon.com jumped into the intensely competitive world of personal electroncs creating and launching Kindle. And then upped the stakes against competitors by enhancing that into Kindle Fire. And when traditional IT suppliers like HP and Dell were slow to help small (or any) business move toward cloud computing Amazon launched its own network services to help the market shift.

Mr. Bezos' language regarding his intentions post acquisition are quite telling, "change… is essential… with or without new ownership….need to invent…need to experiment."

And that is exactly what the news industry needs today. Today's leaders are HuffingtonPost.com, Marketwatch.com and other web sites with wildly different business models than traditional paper media. WaPo success will require transforming a dying company, tied to an old success formula, into a trend-aligned organization that give people what they want, when they want it, at a profit.

And it's hard to think of someone better experienced, or skilled, than Jeff Bezos to provide that kind of leadership. With just a little imagination we can imagine some rapid moves:

- distribution of all content via Kindle style eReaders, rather than print. Along with dramatically increasing the cost of paper subscriptions and daily paper delivery

- Instead of a "one size fits all" general purpose daily paper, packaging news into more fitting targeted products. Sports stories on sports sites. Business stories on business sites. Deeper, longer stories into ebooks available for $.99 purchase. And repackaging of stories that cover longer time spans into electronic short-books for purchase.

- Packaging content into Facebook locations for targeted readers. Tying ads into these social media sites, and promoting ad sales for small, local businesses to the Facebook sites.

- Or creating an ala carte approach to buying various news and entertainment in an iTunes or Netflix style environment (or on those sites)

- Robustly attracting readers via connecting content with social media, including Twitter, to meet modern needs for immediacy, headline knowledge and links to deeper stories — with sales of ads onto social media

- Tying electronic coupons, and buy-it-now capabilities to ads linked to appropriate content

- Retargeting advertising sales from general purpose to targeted delivery at specific readers, with robust packages of on-line coupons, links to specials and fast, impulse purchase capability

- Increased use of bloggers and ad hoc writers to supplement staff in order to offer opinions and insights quickly, but at lower cost.

- Changes in compensation linked to page views and readership, just as revenue is linked to same.

We've watched a raft of newspapers and magazines disappear. This has not been a failure of journalism, but rather a failure of business leaders to address shifting markets and transform old organizations to meet modern needs. It's not a quality problem, but rather a failure of strategy to adapt to shifting markets. And that's a lesson every business leaders needs to note, because today, as I wrote in April, 2012, every company has to behave like a tech company!

Doing more of the same, cutting costs and rich egos won't fix a newspaper. Only the willingness to experiment and find new solutions which transform these organizations into something very different, well beyond print, will work. Let's hope Mr. Bezos brings the same zest for addressing these challenges and aligning with market needs he brought to Amazon. To a large extent, the future of news and "freedom of the press" may well depend upon it.