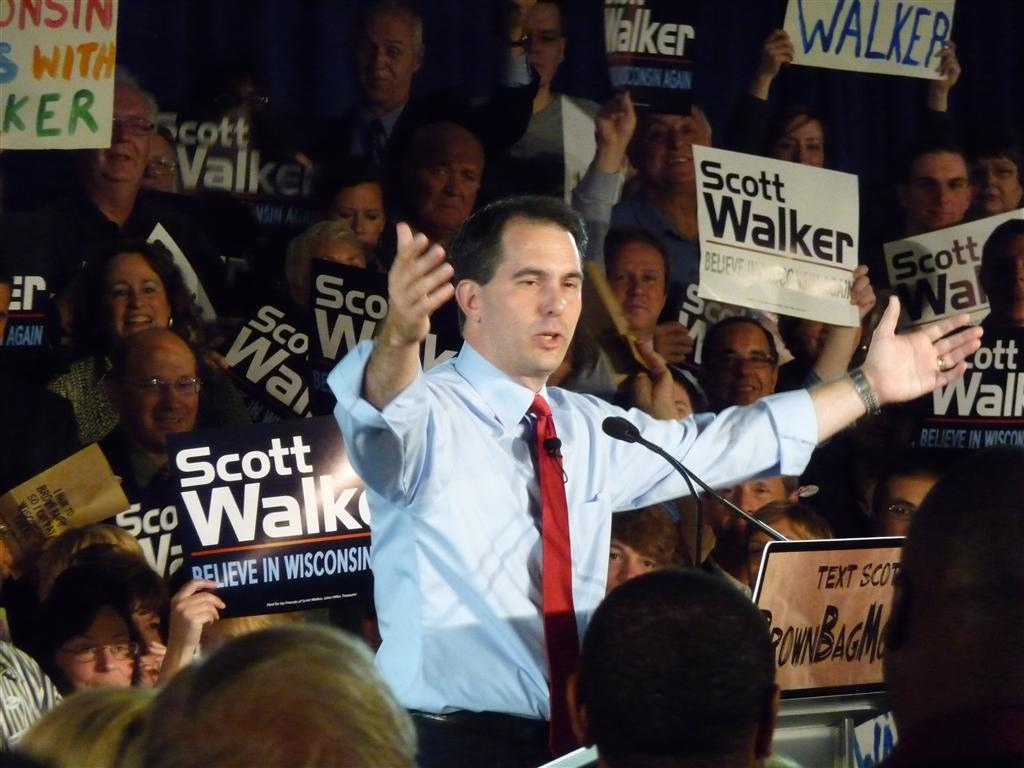

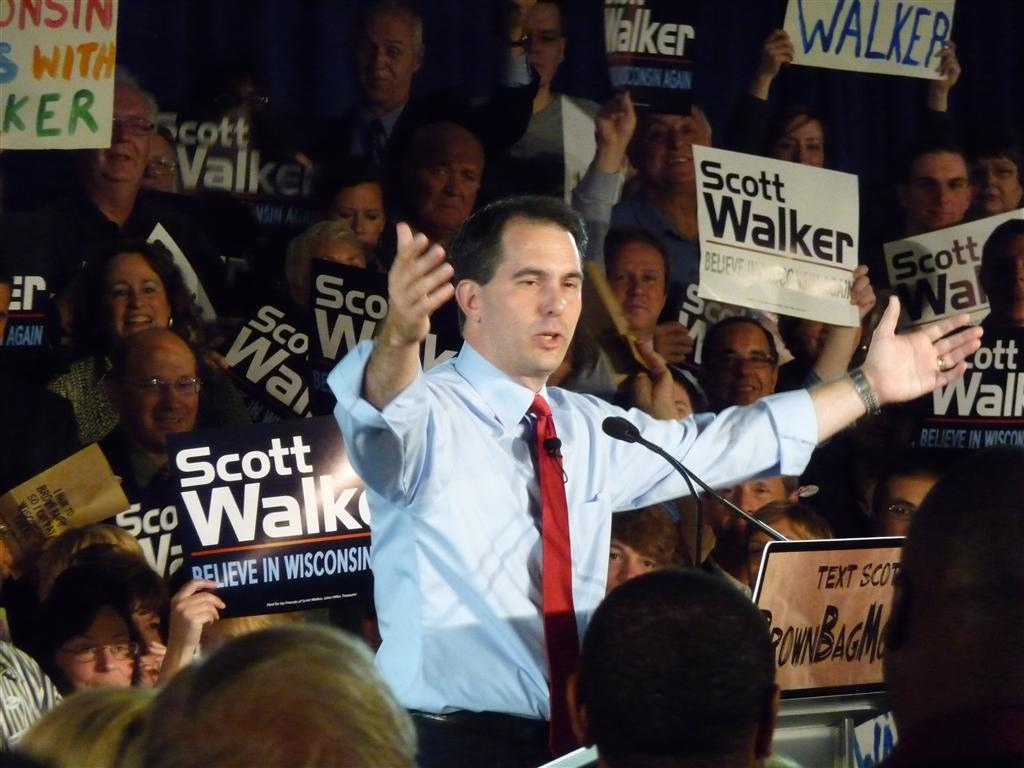

by Adam Hartung | Feb 18, 2015 | Current Affairs, Leadership

There has been a hullabaloo lately about Wisconsin Governor Walker’s lack of a degree. Some think this is a big deal, while others think almost nobody cares. In the end, we all should care about the formal education of any of our leaders. In government, business and elsewhere.

In Forbes magazine, 1998, famed management guru Peter Drucker wrote, “Get the assumptions wrong and everything that follows from them is wrong.” This is really important, because most leaders make most of their decisions based on assumptions. And many of those assumptions are based on how much, and how broad, that leader’s education.

We all make decisions on beliefs. It is easy to have incorrect beliefs. Early doctors believed that infections were due to bad blood, so they used bleeding as a cure-all for many wounds and illnesses. Untold millions of people died from this practice. A bad assumption, based on belief rather than formal study (in this case of the circulatory system) proved fatal.

In business, for thousands of years most sailors had no education about the curvature of the earth and its rotation the sun, thus they believed the world was flat and refused to sail further out to sea than the ability to keep their eyes on a shoreline. This limited trade, and delayed expansion into new markets.

Or, more recently, Steve Ballmer assumed that anyone using a smartphone would want a keyboard – because Blackberry dominated the market and had a keyboard. Thus he laughed at the iPhone launch. Oops. His assumption, and belief about the user experience, caused Microsoft to delay its entry into mobile markets and smartphones several years. Even though he had not studied smartphone user needs. Now Apple has half the smartphone market, while Blackberry and Microsoft each have less than 5%.

There are countless examples of bad decisions made when people use the wrong assumptions. At this time in Oklahoma, Texas and Colorado politicians are voting to refuse upgrading history education because the new curriculum is unacceptable to them. Their assumptions about America’s history are so strong that any factual evidence which might change those assumptions is so threatening that these politicians would prefer students be taught a fictitious history.

Our assumptions are built early in life. All through childhood our parents, aunts, uncles, religious leaders, mentors and teachers fill us with information. We process this information and build layers of assumptions. These assumptions help us to make decisions by allowing us to react based upon what we believe, rather than having to scurry around and do a research project every time a decision is required. Thus, the older we become the deeper these assumptions lie – and the more we rely on them as we undertake less and less education. As we age we decide based upon our beliefs, and less based upon any observable facts. Actually, we’ll often choose to ignore facts which indicate our assumptions and beliefs might be wrong (we call this a bias in others, and common sense when we do it ourselves.)

The more education you have, the more you can build assumptions that are likely to align with reality. It is no accident that the U.S. military uses education as a basis for promotions – rather than battlefield heroics. To move up requires officers go to war college and learn about history, politics, leadership and battles going back to long before the birth of Jesus. Good knowledge helps officers to be smarter about how to prepare for battle, organize for battle, conduct warfare, lead troops, treat a vanquished enemy and talk to the politicians for whom they work. Just look at the degrees amongst our military’s Colonels and General Officers and you find a plethora of masters and doctorate degrees. Education has long proven to be a superior warfare skill – especially when the enemy is operating on belief, guts and fight.

There are many accomplished people lacking degrees. But we should note they were successful very narrowly, and frequently in business. Steve Jobs, Bill Gates and Mark Zuckerberg are clearly high IQ people. But their success was based on founding a business at a time of technological revolution, and then building that business with zealousness. And the luck of being in the right place at the right time with a new piece of technology. They were/are not asked to be widely acclaimed in a broad spectrum of capabilities such as diplomacy, historical accuracy, legal limitations, cultural differences, the arts, scientific advances in multiple fields, warfare tactics, etc. They were not asked to develop a turnaround plan for a bankrupt auto manufacturer at the height of the Great Recession. For all their great wealth creation, they would not be what were once called “Renaissance men.”

When Governor Walker attacks the educated, and labels them as “elites,” it should be noted that their backgrounds often mean they have more points of view to evaluate, and are more considered about the various risks which are being created by taking any specific action. Many Harvard or Columbia MBAs could never be entrepreneurs because they see the many reasons a business would likely fail, and thus they are reticent to commit. Yet, that same wider knowledge allows them to be more thoughtful when evaluating the options and making decisions regarding opening new plants, negotiating with unions, expanding distribution and financing options.

Further, while it is true that you can be smart and not have a degree, the number of those who have degrees yet lack intelligence is a much, much smaller number. If one is to err in picking those you want to have advise you, or represent you, the degree(s) is not a bad first step toward identifying who is likely to provide the best insight and offer the most help.

Further, there is nothing about a degree which limits one’s ability to fight. Look at Senator Cruz from Texas. Senator Cruz’s politics seem to be somewhat aligned with Governor Walker’s, and he is widely acknowledged as a serious fighter, yet he boasts an undergraduate degree from Princeton as well as graduating from Harvard Law School. An educational background anyone would label as “elitist” and remarkably similar to President Obama’s – whose background Governor Walker has thoroughly maligned.

We expect our leaders to be widely read, and keenly aware of the complexities of life. We want our attorney’s to have law degrees and pass the bar exam. We want our physicians to have medical degrees and pass the Boards. Increasingly we want our business leaders to have MBAs. We understand that education informs our minds, and helps us develop assumptions for making good decisions. We should not belittle this, nor be accepting of someone who implies that lacking a formal education is meaningless.

by Adam Hartung | Sep 17, 2014 | Current Affairs, Disruptions, In the Whirlpool, Leadership, Lock-in

Sony was once the leader in consumer electronics. A brand powerhouse who’s products commanded a premium price and were in every home. Trinitron color TVs, Walkman and Discman players, Vaio PCs. But Sony has lost money for all but one quarter across the last 6 years, and company leaders just admitted the company will lose over $2B this year and likely eliminate its dividend.

McDonald’s created something we now call “fast food.” It was an unstoppable entity that hooked us consumers on products like the Big Mac, Quarter Pounder and Happy Meal. An entire generation was seemingly addicted to McDonald’s and raised their families on these products, with favorable delight for the ever cheery, clown-inspired spokesperson Ronald McDonald. But now McDonald’s has hit a growth stall, same-store sales are down and the Millenial generation has turned its nose up creating serious doubts about the company’s future.

Radio Shack was the leader in electronics before we really had a consumer electronics category. When we still bought vacuum tubes to repair radios and TVs, home hobbyists built their own early versions of computers and video games worked by hooking them up to TVs (Atari, etc.) Radio Shack was the place to go. Now the company is one step from bankruptcy.

Sears created the original non-store shopping capability with its famous catalogs. Sears went on to become a Dow Jones Industrial Average component company and the leading national general merchandise retailer with powerhouse brands like Kenmore, Diehard and Craftsman. Now Sears’ debt has been rated the lowest level junk, it hasn’t made a profit for 3 years and same store sales have declined while the number of stores has been cut dramatically. The company survives by taking loans from the private equity firm its Chairman controls.

How in the world can companies be such successful pioneers, and end up in such trouble?

Markets shift. Things in the world change. What was a brilliant business idea loses value as competitors enter the market, new technologies and solutions are created and customers find they prefer alternatives to your original success formula. These changed markets leave your company irrelevant – and eventually obsolete.

Unfortunately, we’ve trained leaders over the last 60 years how to be operationally excellent. In 1960 America graduated about the same number of medical doctors, lawyers and MBAs from accredited, professional university programs. Today we still graduate about the same number of medical doctors every year. We graduate about 6 times as many lawyers (leading to lots of jokes about there being too many lawyers.) But we graduate a whopping 30 times as many MBAs. Business education skyrocketed, and it has become incredibly normal to see MBAs at all levels, and in all parts, of corporations.

The output of that training has been a movement toward focusing on accounting, finance, cost management, supply chain management, automation — all things operational. We have trained a veritable legion of people in how to “do things better” in business, including how to measure costs and operations in order to make constant improvements in “the numbers.” Most leaders of publicly traded companies today have a background in finance, and can discuss the P&L and balance sheets of their companies in infinite detail. Management’s understanding of internal operations and how to improve them is vast, and the ability of leaders to focus an organization on improving internal metrics is higher than ever in history.

But none of this matters when markets shift. When things outside the corporation happen that makes all that hard work, cost cutting, financial analysis and machination pretty much useless. Because today most customers don’t really care how well you make a color TV or physical music player, since they now do everything digitally using a mobile device. Nor do they care for high-fat and high-carb previously frozen food products which are consistently the same because they can find tastier, fresher, lighter alternatives. They don’t care about the details of what’s inside a consumer electronic product because they can buy a plethora of different products from a multitude of suppliers with the touch of a mobile device button. And they don’t care how your physical retail store is laid out and what store-branded merchandise is on the shelves because they can shop the entire world of products – and a vast array of retailers – and receive deep product reviews instantaneously, as well as immediate price and delivery information, from anywhere they carry their phone – 24×7.

“Get the assumptions wrong, and nothing else matters” is often attributed to Peter Drucker. You’ve probably seen that phrase in at least one management, convention or motivational presentation over the last decade. For Sony, McDonald’s, Radio Shack and Sears the assumptions upon which their current businesses were built are no longer valid. The things that management assumed to be true when the companies were wildly profitable 2 or 3 decades ago are no longer true. And no matter how much leadership focuses on metrics, operational improvements and cost cutting – or even serving the remaining (if dwindling) current customers – the shift away from these companies’ offerings will not stop. Rather, that shift is accelerating.

It has been 80 years since Harvard professor Joseph Schumpeter described “creative destruction” as the process in which new technologies obsolete the old, and the creativity of new competitors destroys the value of older companies. Unfortunately, not many CEOs are familiar with this concept. And even fewer ever think it will happen to them. Most continue to hope that if they just make a few more improvements their company won’t really become obsolete, and they can turn around their bad situation.

For employees, suppliers and investors such hope is a weak foundation upon which to rely for jobs, revenues and returns.

According to the management gurus at McKinsey, today the world population is getting older. Substantially so. Almost no major country will avoid population declines over next 20 years, due to low birth rates. Simultaneously, better healthcare is everywhere, and every population group is going to live a whole lot (I mean a WHOLE LOT) longer. Almost every product and process is becoming digitized, and any process which can be done via a computer will be done by a computer due to almost free computation. Global communication already is free, and the bandwidth won’t stop growing. Secrets will become almost impossible to keep; transparency will be the norm.

These trends matter. To every single business. And many of these trends are making immediate impacts in 2015. All will make a meaningful impact on practically every single business by 2020. And these trends change the assumptions upon which every business – certainly every business founded prior to 2000 – demonstrably.

Are you changing your assumptions, and your business, to compete in the future? If not, you could soon look at your results and see what the leaders at Sony, McDonald’s, Radio Shack and Sears are seeing today. That would be a shame.

by Adam Hartung | Jan 15, 2014 | Current Affairs, Leadership

The S&P 500 had a great 2013. Up 29.7% – its best performance since 1997. The Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA) ended the year up 26.5% – its best performance since 1995. And this happened as economic growth lowered the unemployment rate to 6.7% in December – the lowest rate in 5 years. And overall real estate had double-digit price gains, lowering significantly the number of underwater mortgages.

But if we go back to the beginning of 2013, most Wall Street forecasters were predicting a very different outcome. Long suffering bear Harry Dent predicted a stock crash in 2013 that would last through 2014, and ongoing cratering in real estate values. And bear Gina Martin Adams of Wells Fargo Securities predicted a market decline in 2013, a forecast she clung to and fully supported, despite a rising market, when predicting an imminent crash in September. Morgan Stanley’s Adam Parker also predicted a flat market, as did UBS analyst Jonathan Golub.

How could professionals who are paid so much money, have so many resources and the backing of such outstanding large and qualified institutions be so wrong?

An over-reliance on quantitative analysis, combined with using the wrong assumptions.

The conventional approach to Wall Street forecasting is to use computers to amass enormously complex spreadsheets combining reams of numbers. Computer models are built with thousands of inputs, and tens of millions of data points. Eventually the analysts start to believe that the sheer size of the models gives them validity. In the analytical equivalent of “mine is bigger than yours” the forecasters rely on their model’s complexity and sheer size to self-validate their output and forecasts.

In the end these analysts come up with specific forecast numbers for interest rates, earnings, momentum indicators and multiples (price/earnings being key.) Their faith that the economy and market can be reduced to numbers on spreadsheets leads them to similar faith in their forecasts.

But, numbers are often the route to failure. In the late 1990s a team of Wall Street traders and Nobel economists became convinced their ability to model the economy and markets gave them a distinct investing advantage. They raised $1billion and formed Long Term Capital (LTC) to invest using their complex models. Things worked well for 3 years, and faith in their models grew as they kept investing greater amounts.

But then in 1998 downdrafts in Asian and Russian markets led to a domino impact which cost Long Term Capital $4.6B in losses in just 4 months. LTC lost every dime it ever raised, or made. But worse, the losses were so staggering that LTC’s failure threatened the viability of America’s financial system. The banks, and economy, were saved only after the Federal Reserve led a bailout financed by 14 of the leading financial institutions of the time.

Incorrect assumptions played a major part in how Wall Street missed the market prediction for 2013. All models are based on assumptions. And, as Peter Drucker famously said, “if you get the assumptions wrong everything you do thereafter will be wrong as well” — regardless how complex and vast the models.

Conventional wisdom held that conservative economic policies underpin market growth, and the more liberal Democratic fiscal policies combined with a liberal federal reserve monetary program would bode poorly for investors and the economy in 2013. These deeply held assumptions were, of course, reinforced by a slew of conservative commentators that supported the notion that America was on the brink of runaway inflation and economic collapse. The BIAS (Beliefs, Interpretations, Assumptions and Strategies) of the forecasters found reinforcement almost daily from the rhetoric on CNBC, Bloomberg, Fox News and other programs widely watched by business people from Wall Street to Main Street.

Interestingly, when Obama was re-elected in 2012 a not-so-well-known investment firm in Columbus, OH – far from Wall Street – took an alternative look at the data when forecasting 2013. Polaris Financial Partners took a deep dive into the history of how markets perform when led by traditional conservative vs. liberal policies and reached the startling conclusion that Obama’s programs, including the Affordable Care Act, would actually spur investment, market growth, jobs and real estate! They had forecast a double digit increase in all major averages for 2012 and extended that same double digit forecast into 2013 – far more optimistic than anyone on Wall Street.

CEO Bob Deitrick and partner Steven Morgan concluded that the millenium’s first decade had been lost. Despite Republican leadership, the eqity markets were, at best, sideways. There were fewer people actually working in 2008 than in 2000; a net decrease in jobs. After a near-collapse in the banking system, due to deregulated computer-model based trading in complex derivatives, real estate and equity prices had collapsed.

“Fourteen years of stock market gains were wiped out in 17 months from October, 2007 to March, 2009” lamented Deitrick.

Polaris Partners concluded the situation was eerily similar to the 1920s at the end of Hoover’s administration. A situation which was eventually resolved via Keynesian policies of increased fiscal spending while interest rates were low, and federal reserve intervention to both expand the money supply and increase the velocity of money under Republican Fed chief Marriner Eccles and Democratic President Franklin Roosevelt.

While most people conventionally think that tax cuts led to economic growth during the Reagan administration, Polaris Financial turned that assumption upside down and put the biggest positive economic impact on the roll-back of tax cuts a year after being pushed by Reagan and passing Congress. Their analysis of the 1980 recovery focused on higher defense and infrastructure spending (fiscal policy,) a massive increase in debt (the largest peacetime debt increase ever) coupled with a more balanced tax code post-TEFRA.

Thus, eschewing complex econometric models, elaborately detailed spreadsheets of earnings and rolling momentum indicators, Polaris Financial focused instead on identifying the assumptions they believeed would most likely drive the economy and markets in 2013. They focused on the continuation of Chairman Bernanke’s easy monetary policy, and long-term fiscal policies designed to funnel money into investments which would incent job creation and GDP growth leading to an improvement in house values, and consumer spending, while keeping interest rates at historically low levels. All of which would bode extremely well for thriving equity markets.

The vitriol has been high amongst those who support, and those who oppose, the economic policies of Obama’s administration since 2008. But vitriol does not support, nor replace, good forecasting. Too often forecasters predict what they want to happen, what they hope will happen, based upon their view of history, their traing and background, and their embedded assumptions. They believe in the certainty of long-held assumptions, and forecast from that base.

But as Polaris Financial pointed out, in beating every major Wall Street firm over the last 2 years, good forecasting relies on looking carefully at historical outcomes, and understanding the context in which those results happened. Rather than relying on an interpretation of the outcome,they looked instead at the facts and the situation; the actions and the outcomes in its context. In an economy, everything is relative to the context. There are no absolute programs that are universally the right thing to do. Every policy action, and every monetary action, is dependent upon initial conditions as well as the action itself.

Too few forecasters take into account both the context as well as the action. And far too few do enough analysis of assumptions, preferring instead to rely on reams of numerical analysis which may, or may not, relate to the current situation. And are often linked to assumptions underlying the model’s construction – assumptions which could be out of date or simply wrong.

The folks at Polaris Financial Partners remain optimistic about the economy and markets for the next two years. They point out that unemployment has dropped faster under Obama, and from a much higher level, than during the Reagan administration. They see the Affordable Care Act opening more flexibility for health care, creating a rise in entrepreneurship and innovation (especially biotechnology) that will spur economic growth. Deitrick and Morgan see tax programs, and rising minimum wage trends, working toward better income balancing, and greater monetary velocity aiding GDP growth. Their projection is for improving real estate values, jobs growth, and minimal inflation leading to higher indexes – such as 20,000 on the DJIA and 2150 on the S&P.

Bob Deitrick co-authored, with Lew Goldfarb, “Bulls, Bears and the Ballot Box” in 2012 analyzing Presidential economic policies, Federal Reserve policies and stock market performance.

by Adam Hartung | Jul 18, 2013 | Current Affairs, Defend & Extend, In the Whirlpool, Leadership, Lock-in

Sears has performed horribly since acquired by Fast Eddie Lampert's KMart in 2005. Revenues are down 25%, same store sales have declined persistently, store margins have eroded and the company has recently taken to reporting losses. There really hasn't been any good news for Sears since the acquisition.

Bloomberg Businessweek made a frontal assault on CEO Edward Lampert's leadership at Sears this week. Over several pages the article details how a "free market" organization installed by Mr. Lampert led to rampant internal warfare and an inability for the company to move forward effectively with programs to improve sales or profits. Meanwhile customer satisfaction has declined, and formerly valuable brands such as Kenmore and Craftsman have become industry also-rans.

Because the Lampert controlled hedge fund ESL Investments is the largest investor in Sears, Mr. Lampert has no risk of being fired. Even if Nobel winner Paul Krugman blasts away at him. But, if performance has been so bad – for so long – why does the embattled Mr. Lampert continue to lead in the same way? Why doesn't he "fire" himself?

By all accounts Mr. Lampert is a very smart man. Yale summa cum laude and Phi Beta Kappa, he was a protege of former Treasury Secretay Robert Rubin at Goldman Sach before convincing billionaire Richard Rainwater to fund his start-up hedge fund – and quickly make himself the wealthiest citizen in Connecticut.

If the problems at Sears are so obvious to investors, industry analysts, economics professors, management gurus and journalists why doesn't he simply change?

Mr. Lampert, largely because of his success, is a victim of BIAS. Deep within his decision making are his closely held Beliefs, Interpretations, Assumptions and Strategies. These were created during his formative years in college and business. This BIAS was part of what drove his early success in Goldman, and ESL. This BIAS is now part of his success formula – an entire set of deeply held convictions about what works, and what doesn't, that are not addressed, discussed or even considered when Mr. Lampert and his team grind away daily trying to "fix" declining Sears Holdings.

This BIAS is so strong that not even failure challenges them. Mr. Lampert believes there is deep value in conventional retail, and real estate. He believes strongly in using "free market competition" to allocate resources. He believes in himself, and he believes he is adding value, even if nobody else can see it.

Mr. Lampert assumes that if he allows his managers to fight for resources, the best programs will reach the top (him) for resourcing. He assumes that the historical value in Sears and its house brands will remain, and he merely needs to unleash that value to a free market system for it to be captured. He assumes that because revenues remain around $35B Sears is not irrelevant to the retail landscape, and the company will be revitalized if just the right ideas bubble up from management.

Mr. Lampert inteprets the results very different from analysts. Where outsiders complain about revenue reductions overall and same store, he interprets this as an acceptable part of streamlining. When outsiders say that store closings and reduced labor hurt the brand, he interprets this as value-added cost savings. When losses appear as a result of downsizing he interprets this as short-term accounting that will not matter long-term. While most investors and analysts fret about the overall decline in sales and brands Mr. Lampert interprets growing sales of a small integrated retail program as a success that can turn around the sinking behemoth.

Mr. Lampert's strategy is to identify "deep value" and then tenaciously cut costs, including micro-managing senior staff with daily calls. He believes this worked for Warren Buffett, so he believes it will continue to be a successful strategy. Whether such deep value continues to exist – especially in conventional retail – can be challenged by outsiders (don't forget Buffett lost money on Pier 1,) but it is part of his core strategy and will not be challenged. Whether cost cutting does more harm than good is an unchallenged strategy. Whether micro-managing staff eats up precious resources and leads to unproductive behavior is a leadership strategy that will not change. Hiring younger employees, who resemble Mr. Lampert in quick thinking and intellect (if not industry knowledge or proven leadership skills) is a strategy that will be applied even as the revolving door at headquarters spins.

The retail market has changed dramatically, and incredibly quickly. Advances in internet shopping, technology for on-line shopping (from mobile devices to mobile payments) and rapid delivery have forever altered the economics of retailing. Customer ease of showrooming, and desire to shop remotely means conventional retail has shrunk, and will continue to shrink for several years. This means the real challenge for Sears is not to be a better Sears as it was in 2000 — but to become something very different that can compete with both WalMart and Amazon – and consumer goods manufacturers like GE (appliances) and Exide (car batteries.)

There is no doubt Mr. Lampert is a very smart person. He has made a fortune. But, he and Sears are a victim of his BIAS. Poor results, bad magazine articles and even customer complaints are no match for the BIAS so firmly underlying early success. Even though the market has changed, Mr. Lampert's BIAS has him (and his company) in internal turmoil, year after year, even though long ago outsiders gave up on expecting a better result.

Even if Sears Holdings someday finds itself in bankruptcy court, expect Mr. Lampert to interpret this as something other than a failure – as he defends his BIAS better than he defends its shareholders, employees, suppliers and customers.

What is your BIAS? Are you managing for the needs of changing markets, or working hard to defend doing more of what worked in a bygone era? As a leader, are you targeting the future, or trying to recapture the past? Have market shifts made your beliefs outdated, your interpretations of what happens around you faulty, your assumptions inaccurate and your strategies hurting results? If any of this is true, it may be time you address (and change) your BIAS, rather than continuing to invest in more of the same. Or you may well end up like Sears.