by Adam Hartung | Nov 6, 2013 | Defend & Extend, Innovation, Leadership, Web/Tech

Can you believe it has been only 12 years since Apple introduced the iPod? Since then Apple’s value has risen from about $11 (January, 2001) to over $500 (today) – an astounding 45X increase.

With all that success it is easy to forget that it was not a “gimme” that the iPod would succeed. At that time Sony dominated the personal music world with its Walkman hardware products and massive distribution through consumer electronics chains such as Best Buy, and broad-line retailers like Wal-Mart. Additionally, Sony had its own CD label, from its acquisition of Columbia Records (renamed CBS Records,) producing music. Sony’s leadership looked impenetrable.

But, despite all the data pointing to Sony’s inevitable long-term domination, Apple launched the iPod. Derided as lacking CD quality, due to MP3’s compression algorithms, industry leaders felt that nobody wanted MP3 products. Sony said it tried MP3, but customers didn’t want it.

All the iPod had going for it was a trend. Millions of people had downloaded MP3 songs from Napster. Napster was illegal, and users knew it. Some heavy users were even prosecuted. But, worse, the site was riddled with viruses creating havoc with all users as they downloaded hundreds of millions of songs.

Eventually Napster was closed by the government for widespread copyright infreingement. Sony, et.al., felt the threat of low-priced MP3 music was gone, as people would keep buying $20 CDs. But Apple’s new iPod provided mobility in a way that was previously unattainable. Combined with legal downloads, including the emerging Apple Store, meant people could buy music at lower prices, buy only what they wanted and literally listen to it anywhere, remarkably conveniently.

The forecasted “numbers” did not predict Apple’s iPod success. If anything, good analysis led experts to expect the iPod to be a limited success, or possibly failure. (Interestingly, all predictions by experts such as IDC and Gartner for iPhone and iPad sales dramatically underestimated their success, as well – more later.) It was leadership at Apple (led by the returned Steve Jobs) that recognized the trend toward mobility was more important than historical sales analysis, and the new product would not only sell well but change the game on historical leaders.

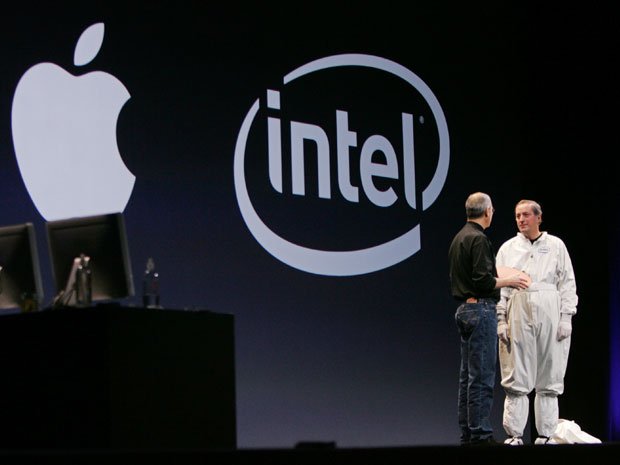

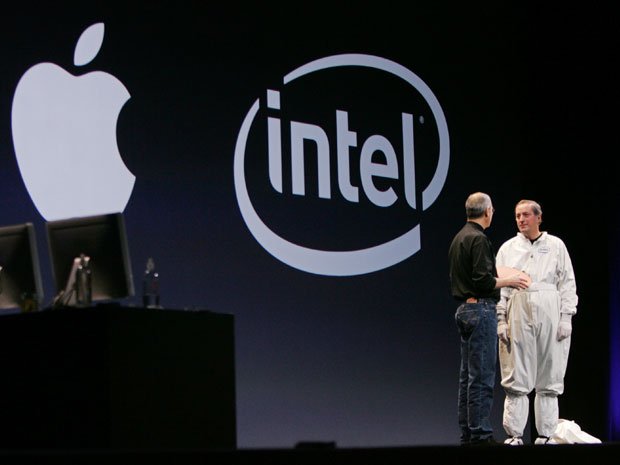

Which takes us to the mistake Intel made by focusing on “the numbers” when given the opportunity to build chips for the iPhone. Intel was a very successful company, making key components for all Microsoft PCs (the famous WinTel [for Windows+Intel] platform) as well as the Macintosh. So when Apple asked Intel to make new processors for its mobile iPhone, Intel’s leaders looked at the history of what it cost to make chips, and the most likely future volumes. When told Apple’s price target, Intel’s leaders decided they would pass. “The numbers” said it didn’t make sense.

Uh oh. The cost and volume estimates were wrong. Intel made its assessments expecting PCs to remain strong indefinitely, and its costs and prices to remain consistent based on historical trends. Intel used hard, engineering and MBA-style analysis to build forecasts based on models of the past. Intel’s leaders did not anticipate that the new mobile trend, which had decimated Sony’s profits in music as the iPod took off, would have the same impact on future sales of new phones (and eventually tablets) running very thin apps.

Harvard innovation guru Clayton Christensen tells audiences that we have complete knowledge about the past. And absolutely no knowledge about the future. Those who love numbers and analysis can wallow in reams and reams of historical information. Today we love the “Big Data” movement which uses the world’s most powerful computers to rip through unbelievable quantities of historical data to look for links in an effort to more accurately predict the future. We take comfort in thinking the future will look like the past, and if we just study the past hard enough we can have a very predictible future.

But that isn’t the way the business world works. Business markets are incredibly dynamic, subject to multiple variables all changing simultaneously. Chaos Theory lecturers love telling us how a butterfly flapping its wings in China can cause severe thunderstorms in America’s midwest. In business, small trends can suddenly blossom, becoming major trends; trends which are easily missed, or overlooked, possibly as “rounding errors” by planners fixated on past markets and historical trends.

Markets shift – and do so much, much faster than we anticipate. Old winners can drop remarkably fast, while new competitors that adopt the trends become “game changers” that capture the market growth.

In 2000 Apple was the “Mac” company. Pretty much a one-product company in a niche market. And Apple could easily have kept trying to defend & extend that niche, with ever more problems as Wintel products improved.

But by understanding the emerging mobility trend leadership changed Apple’s investment portfolio to capture the new trend. First was the iPod, a product wholly outside the “core strengths” of Apple and requiring new engineering, new distribution and new branding. And a product few people wanted, and industry leaders rejected.

Then Apple’s leaders showed this talent again, by launching the iPhone in a market where it had no history, and was dominated by Motorola and RIMM/BlackBerry. Where, again, analysts and industry leaders felt the product was unlikely to succeed because it lacked a keyboard interface, was priced too high and had no “enterprise” resources. The incumbents focused on their past success to predict the future, rather than understanding trends and how they can change a market.

Too bad for Intel. And Blackberry, which this week failed in its effort to sell itself, and once again changed CEOs as the stock hit new lows.

Then Apple did it again. Years after Microsoft attempted to launch a tablet, and gave up, Apple built on the mobility trend to launch the iPad. Analysts again said the product would have limited acceptance. Looking at history, market leaders claimed the iPad was a product lacking usability due to insufficient office productivity software and enterprise integration. The numbers just did not support the notion of investing in a tablet.

Anyone can analyze numbers. And today, we have more numbers than ever. But, numbers analysis without insight can be devastating. Understanding the past, in grave detail, and with insight as to what used to work, can lead to incredibly bad decisions. Because what really matters is vision. Vision to understand how trends – even small trends – can make an enormous difference leading to major market shifts — often before there is much, if any, data.

by Adam Hartung | Aug 25, 2010 | Books, In the Rapids, Leadership, Lock-in

Summary:

- We are biased toward doing what we know how to do, rather than something new

- We like to think we can forever grow by keeping close to what we know – that’s a myth

- Growth only comes from entering growth markets – whether we know much about them or not

- To grow you have to keep yourself in growth markets, and it is dangerous to limit your prospects to projects/markets that are “core” or “adjacent to core”

Recently a popular business book has been Profit from the Core. This book proposes the theory that if you want to succeed in business you should do projects that are either in your “core,” or “adjacent to your core.” Don’t go off trying to do something new. The further you move from your “core” the less likely you will succeed. Talk about an innovation killer! CEOs that like this book are folks who don’t want much new from their employees.

I was greatly heartened by a well written blog article at Growth Science International (www.GrowthSci.com) “Profit from Your Core, or Not.. The Myth of Adjacencies.” Author Thomas Thurston does a masterful job of pointing out that the book authors fall into the same deadly trap as Jim Collins and Tom Peters. They use hindsight primarily as the tool to claim success. Their analysis looks backward – trying to explain only past events. In doing so they cleverly defined terms so their stories seemed to prove their points. But they are wholly unable to be predictive. And, if their theory isn’t predictive, then what good is it? If you can’t use their approach to give a 98% or 99% likelihood of success, then why bother? According to Mr. Thurston, when he tested the theory with some academic rigor he was unable to find a correlation between success and keeping all projects at, or adjacent to, core.

Same conclusion we came to when looking at the theories proposed by Jim Collins and Tom Peters. It sounds good to be focused on your core, but when we look hard at many companies it’s easy to find large numbers that simply do not succeed even though they put a lot of effort into understanding their core, and pouring resources into protecting that core with new core projects and adjacency projects. Markets don’t care about whatever you define as core or adjacent.

It feels good, feels right, to think that “core” or “adjacent to core” projects are the ones to do. But that feeling is really a bias. We perceive things we don’t know as more risky than thing we know. Whether that’s true or not. We perceive bottled water to be more pure than tap water, but all studies have shown that in most cities tap water is actually lower in free particles and bacteria than bottled – especially if the bottle has sat around a while.

What we perceive as risk is based upon our background and experience, not what the real, actual risk may be. Many people still think flying is riskier than driving, but every piece of transportation analysis has shown that commercial flying is about the safest of all transportation methods – certainly much safer than anything on the roadway. We also now know that computer flown aircraft are much safer than pilot flown aircraft – yet few people like the idea of a commercial drone which has no pilot as their transportation. Even though almost all commercial flight accidents turn out to be pilot error – and something a computer would most likely have overcome. We just perceive autos as less risky, because they are under our control, and we perceive pilots as less risky because we understand a pilot much better than we understand a computer.

We are biased to do what we’ve always done – to perpetuate our past. And our businesses are like that as well. So we LOVE to read a book that says “stick close to your known technology, known customers, known distribution system – stick close to what you know.” It reinforces our bias. It justifies us not doing what we perceive as being risky. Even though it is really, really, really lousy advice. It just feels so good – like sugary cereal for breakfast – that we justify it in our minds – like saying “breakfast is the most important meal of the day” as we consume food that’s probably less healthy than the box it came in!

There is no correlation between investing in your core, or close to core, projects and high rates of return. Mr. Thurston again points this out. High rates of return come from investing in projects in growth markets. Businesses in growth markets do better, even when poorly managed, than businesses in flat or declining markets. Where there are lots of customers wanting to buy a solution you simply do better than when there are lots of competitors fighting over dwindling customer revenues. Regardless of how well you don’t know the former or do know the latter. Market growth is a much better predictor of success than understanding your “core” and whatever you consider “adjacent.”

Virgin didn’t know anything about airlines before opening one – but international travel from London was set to boom and Virgin did well (as it has done in many new markets.) Apple didn’t know anything about retail music before launching the iPhone and iTunes, but digital music had started booming at Napster and Apple cleaned up. Nike was a shoe company that didn’t know anything about golf merchandise, but it entered the market for all things golf (first with just one club – the driver – followed by other things) by hooking up with Tiger Woods just as he helped promote the sport into dramatic growth.

Success comes from entering new markets where there is growth. Growth can overcome a world of bad management choices. When there are lots of customers with needs to fill, you can make a lot of mistakes and still succeed. To restrict yourself to “core” and “adjacent” invites failure, because your “core” and the “adjacent” markets that you know well simply may not grow. Leaving you in a tough spot seeking higher profits in the face of stiff competition — like Dell today in PCs. Or GM in autos. Sears in retailing. They may know their “core” but that isn’t giving them the growth they want, and need, to succeed in 2010.

by Adam Hartung | Apr 7, 2009 | Current Affairs, Defend & Extend, General, In the Whirlpool, Innovation, Leadership, Lock-in, Science

"GM, Segway unveil Puma urban vehicle" headlines Marketwatch.com. The Puma is an enlarged Segway that can hold 2 people in a sitting position. Both companies are hoping this promotion will create excitement for the not-yet-released product, thus generating a more positive opinion of both companies and establish early demand. Unfortunately, the product isn't anything at all like the iPod and the comparison is way off the mark.

The iPod when released with the iTunes was a disruptive innovation which allowed customers to completely change how they acquired, maintained and managed their access to music. Instead of purchasing entire CDs, people could acquire one song at a time. You no longer needed special media readers, because the tunes could be heard on any MP3 device. And your access was immediate, from the download, without going to a store or waiting for physical delivery. People that had not been music collectors could become collectors far cheaper, and acquire only exactly what they wanted, and listen to the music in their own designed order, or choose random delivery. The source of music changed, the acquisition process changed, the collection management changed, the storage of a collection changed – it changed just about everything about how you acquired and interacted with music. It was not a sustaining innovation, it was disruptive, and it commercialized a movement which had already achieved high interest via Napster. The iPod/iTunes business put Apple into the lead in an industry long dominated by other companies (such as Sony) by bringing in new users and building a loyal following.

Unfortunately, increasing the size of a product that has not yet demonstrated customer efficacy, economic viability or developed a strong following and trying to sell it through an existing distribution system that has long been decried as uneconomic and displeasing to customers is not an iPod experience. And that is what this GM/Segway announcement is trying to do.

Despite all the publicity when it was first announced, the Segway has not developed a strong following. After 7 years of intense marketing, and lots of looks, Segway has sold only 60,000 units globally – a fraction of competitive product such as bicycles, motorized scooters, motorcycles and mass transit. Segway has not "jumped into the lead" in any segment of transportation. It has yet to develop a single dominant application, or a loyal group of followers. The product achieves a smattering of sales, but the vast majority of observers simply say "why?" and comment on the high price. Segway has never come close to achieving the goals of its inventor or its investors.

This product announcement gives us more of the same from Segway. It's the same product, just bigger. We are given precious little information about why someone would own one, other than it supposedly travels 35 miles on $.35 of electricity. But how fast it goes, how long to recharge, how comfortable the ride, whether it can carry anything with you, how it behaves in foul weather, why you should choose it over a Nano from Tata or another small car, or a motorscooter or motorcycle — these are all open items not addressed.

And worse, the product isn't being launched in White Space to answer these questions and build a market. Instead, the announcement says it will be sold through GM dealers. This simply ignores answering why any GM dealer would ever want to sell the thing – given its likely price point, margin, use – why would a dealer want to sell Puma/Segways instead of more expensive, capable and higher margin cars?

Great White Space projects are created by looking into the future and identifying scenarios where this project – its use – can be a BIG winner that will attract large volumes of customers. Second, it addresses competitive lock-ins and creates advantages that don't currently exist and otherwise would not exist. Thirdly, it Disrupts the marketplace as a game changer by bringing in new users that otherwise are out of the market. And fourth it has permission to try anything and everything in the market to create a new Success Formula to which the company can migrate for rapid growth.

This project does none of that. It's use is as unclear as the original Segway, and the scenario in which this would ever be anything other than a novelty for perfect weather inner-city upscale locations is totally unclear. This product captures all the current Lock-ins of the companies involved – trying to Defend & Extend one's technology base and the other's distribution system – rather than build anything new. The product appears simply to be inferior in almost all regards to competitive products, with no description of why it is a game changer to other forms of transportation. And the project is starting with most important decisions pre-announced – rather than permission to try new things. And there is absolutely no statement of how this project will be resourced or funded – by two companies that are both in terrible financial shape.

The iPod and iTunes are brands that turned around Apple. They are role models for how to use Disruptive innovation to resurrect a troubled company. It's really unfortunate to see such wonderful brand names abused by two poorly performing companies without a clue of how to manage innovation. The biggest value of this announcement is it shows just how poorly managed Segway has been – given that it's partnering with a company that is destined to be the biggest bankruptcy ever in history, and known for its inability to understand customer needs and respond effectively.