by Adam Hartung | Jul 11, 2018 | Computing, Growth Stall, Innovation, Investing, Software

The last few quarters sales growth has not been as good for Apple as it once was. The iPhone X didn’t sell as fast as they hoped, and while the Apple Watch outsells the entire Swiss watch industry it does not generate the volumes of an iPhone. And other new products like Apple Pay and iBeacon just have not taken off.

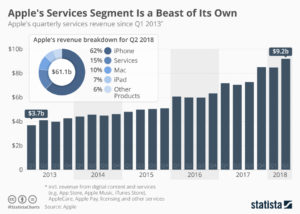

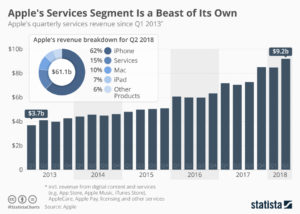

Amidst this slowness, the big winner has been “Apple Services” revenue. This is largely sales of music, videos and apps from iTunes and the App store. In Q2, 2018 revenues reached $9.2B, 15% of total revenues and second only to iPhone sales. Although Apple does not have a majority of smartphone users, the user base it has spends a lot of money on things for Apple devices. A lot of money.

In a bit of “get them the razor so they will buy the razor blades” CEO Tim Cook’s Apple is increasingly relying upon farming the “installed base” of users to drive additional revenues. Leveraging the “installed base” of users is now THE primary theme for growing Apple sales. And even old-tech guys like Warren Buffett at Berkshire Hathaway love it, as they gobble up Apple shares. As do many analysts, and investors. Apple has paid out over $100B to developers for its services, and generated over $40B in revenues for itself – and with such a large base willing to buy things developers are likely to keep providing more products and working to grow sales.

In a bit of “get them the razor so they will buy the razor blades” CEO Tim Cook’s Apple is increasingly relying upon farming the “installed base” of users to drive additional revenues. Leveraging the “installed base” of users is now THE primary theme for growing Apple sales. And even old-tech guys like Warren Buffett at Berkshire Hathaway love it, as they gobble up Apple shares. As do many analysts, and investors. Apple has paid out over $100B to developers for its services, and generated over $40B in revenues for itself – and with such a large base willing to buy things developers are likely to keep providing more products and working to grow sales.

But the risks here should not be taken lightly. At one time Apple’s Macintosh was the #1 selling PC. But it was “closed” and required users buy their applications from Apple. Microsoft offered its “open architecture” and suddenly lots of new applications were available for PCs, which were also cheaper than Macs. Over a few years that “installed base” strategy backfired for Apple as PC sales exploded and Mac sales shrank until it became a niche product with under 10% market share.

Today, Android phones are the #1 smartphone market share platform, and Android devices (like the PC) are much cheaper. Even cheaper are Chinese made products. Although there are problems, the risk exists that someday apps, etc for Android and/or other platforms could become more standard and the larger Android base could “flip” the market.

The history of companies relying on an installed base to grow their company has not gone well. Going back 30 years, AM Multigraphics an ABDick sold small printing presses to schools, government agencies and businesses. After the equipment sale these companies made most of their growth on the printing supplies these presses used. But competitors whacked away at those sales, and eventually new technologies displaced the small presses. The installed base shrank, and both companies disappeared.

Xerox would literally give companies a copier if they would just pay a “per click” charge for service on the machine, and use Xerox toner. Xerox grew like the proverbial weed. Their service and toner revenue built the company. But then people started using much cheaper copiers they could buy, and supply with cheaper consumables. And desktop publishing solutions caused copier use to decline. So much for Xerox growth – and the company rapidly lost relevance. Now Xerox is on the verge of disappearing into Fuji.

HP loved to sell customers cheap ink-jet printer so they bought the ink. But now images are mostly transferred as .jpg, .png or .pdf files and not printed at all. The installed base of HP printers drove growth, until the need for any printing started disappearing.

The point? It is very risky to rely on your installed platform base for your growth. Why? Because competitors with cheaper platforms can come along and offer cheaper consumables, making your expensive platform hard to keep forefront in the market. That’s the classic “innovator’s dilemma” – someone comes along with a less-good solution but it’s cheaper and people say “that’s good enough” thus switching to the cheaper platform. This leaves the innovator stuck trying to defend their expensive platform and aftermarket sales as the market switches to ever better, cheaper solutions.

It’s great that Apple is milking its installed base. That’s smart. But it is not a viable long-term strategy. That base will, someday, be overtaken by a competitor or a new technology. Like, maybe, smart speakers. They are becoming ubiquitous. Yes, today Siri is the #1 voice assistant. But as Echo and Google speaker sales proliferate, can they do to smartphones what smartphones did to PCs? What if one of these companies cooperates with Microsoft to incorporate Cortana, and link everything on the network into the Windows infrastructure? If these scenarios prevail, Apple could/will be in big trouble.

I pointed out in October, 2016 that Apple hit a Growth Stall. When that happens, maintaining 2% growth long-term happens only 7% of the time. I warned investors to be wary of Apple. Why? Because a Growth Stall is an early indicator of an innovation gap developing between the company’s products and emerging products. In this case, it could be a gap between ever enhanced (beyond user needs) mobile devices and really cheap voice activated assistant devices in homes, cars, offices, everywhere. Apple can milk that installed base for a goodly while, but eventually it needs “the next big thing” if it is going to continue being a long-term winner.

by Adam Hartung | Nov 18, 2015 | Current Affairs, Defend & Extend, In the Swamp, In the Whirlpool, Leadership, Web/Tech

Microsoft recently announced it was offering Windows 10 on xBox, thus unifying all its hardware products on a single operating system – PCs, mobile devices, gaming devices and 3D devices. This means that application developers can create solutions that can run on all devices, with extensions that can take advantage of inherent special capabilities of each device. Given the enormous base of PCs and xBox machines, plus sales of mobile devices, this is a great move that expands the Windows 10 platform.

Only it is probably too late to make much difference. PC sales continue falling – quickly. Q3 PC sales were down over 10% versus a year ago. Q2 saw an 11% decline vs year ago. The PC market has been steadily shrinking since 2012. In Q2 there were 68M PCs sold, and 66M iPhones. Hope springs eternal for a PC turnaround – but that would seem increasingly unrealistic.

The big market shift to mobile devices started back in 2007 when the iPhone began challenging Blackberry. By 2010 when the iPad launched, the shift was in full swing. And that’s when Microsoft’s current problems really began. Previous CEO Steve Ballmer went “all-in” on trying to defend and extend the PC platform with Windows 8 which began development in 2010. But by October, 2012 it was clear the design had so many trade-offs that it was destined to be an Edsel-like flop – a compromised product unable to please anyone.

The big market shift to mobile devices started back in 2007 when the iPhone began challenging Blackberry. By 2010 when the iPad launched, the shift was in full swing. And that’s when Microsoft’s current problems really began. Previous CEO Steve Ballmer went “all-in” on trying to defend and extend the PC platform with Windows 8 which began development in 2010. But by October, 2012 it was clear the design had so many trade-offs that it was destined to be an Edsel-like flop – a compromised product unable to please anyone.

By January, 2013 sales results were showing the abysmal failure of Windows 8 to slow the wholesale shift into mobile devices. Ballmer had played “bet the company” on Windows 8 and the returns were not good. It was the failure of Windows 8, and the ill-fated Surface tablet which became a notorious billion dollar write-off, that set the stage for the rapid demise of PCs.

And that demise is clear in the ecosystem. Microsoft has long depended on OEM manufacturers selling PCs as the driver of most sales. But now Lenovo, formerly the #1 PC manufacturer, is losing money – lots of money – putting its future in jeopardy. And Dell, one of the other top 3 manufacturers, recently pivoted from being a PC manufacturer into becoming a supplier of cloud storage by spending $67B to buy EMC. The other big PC manufacturer, HP, spun off its PC business so it could focus on non-PC growth markets.

And, worse, the entire OEM market is collapsing. For the largest 4 PC manufacturers sales last quarter were down 4.5%, while sales for the remaining smaller manufacturers dropped over 20%! With fewer and fewer sales, consolidation is wiping out many companies, and leaving those remaining in margin killing to-the-death competition.

And, worse, the entire OEM market is collapsing. For the largest 4 PC manufacturers sales last quarter were down 4.5%, while sales for the remaining smaller manufacturers dropped over 20%! With fewer and fewer sales, consolidation is wiping out many companies, and leaving those remaining in margin killing to-the-death competition.

Which means for Microsoft to grow it desperately needs Windows 10 to succeed on devices other than PCs. But here Microsoft struggles, because it long eschewed its “channel suppliers,” who create vertical market applications, as it relied on OEM box sales for revenue growth. Microsoft did little to spur app development, and rather wanted its developers to focus on installing standard PC units with minor tweaks to fit vertical needs.

Today Apple and Google have both built very large, profitable developer networks. Thus iOS offers 1.5M apps, and Google offers 1.6M. But Microsoft only has 500K apps largely because it entered the world of mobile too late, and without a commitment to success as it tried to defend and extend the PC. Worse, Microsoft has quietly delayed Project Astoria which was to offer tools for easily porting Android apps into the Windows 10 market.

Microsoft realized it needed more developers all the way back in 2013 when it began offering bonuses of $100,000 and more to developers who would write for Windows. But that had little success as developers were more keen to achieve long-term sales by building apps for all those iOS and Android devices now outselling PCs. Today the situation is only exacerbated.

By summer of 2014 it was clear that leadership in the developer world was clearly not Microsoft. Apple and IBM joined forces to build mobile enterprise apps on iOS, and eventually IBM shifted all its internal PCs from Windows to Macintosh. Lacking a strong installed base of Windows mobile devices, Microsoft was without the cavalry to mount a strong fight for building a developer community.

In January, 2015 Microsoft started its release of Windows 10 – the product to unify all devices in one O/S. But, largely, nobody cared. Windows 10 is lots better than Win8, it has a great virtual assistant called Cortana, and it now links all those Microsoft devices. But it is so incredibly late to market that there is little interest.

Although people keep talking about the huge installed base of PCs as some sort of valuable asset for Microsoft, it is clear that those are unlikely to be replaced by more PCs. And in other devices, Microsoft’s decisions made years ago to put all its investment into Windows 8 are now showing up in complete apathy for Windows 10 – and the new hybrid devices being launched.

AM Multigraphics and ABDick once had printing presses in every company in America, and much of the world. But when Xerox taught people how to “one click” print on a copier, the market for presses began to die. Many people thought the installed base would keep these press companies profitable forever. And it took 30 years for those machines to eventually disappear. But by 2000 both companies went bankrupt and the market disappeared.

Those who focus on Windows 10 and “universal windows apps” are correct in their assessment of product features, functions and benefits. But, it probably doesn’t matter. When Microsoft’s leadership missed the mobile market a decade ago it set the stage for a long-term demise. Now that Apple dominates the platform space with its phones and tablets, followed by a group of manufacturers selling Android devices, developers see that future sales rely on having apps for those products. And Windows 10 is not much more relevant than Blackberry.

by Adam Hartung | Jul 8, 2014 | Current Affairs, Food and Drink, In the Whirlpool, Leadership

Crumbs Bake Shop – a small chain of cupcake shops, almost totally unknown outside of New York City and Washington, DC – announced it was going out of business today. Normally, this would not be newsworthy. Even though NASDAQ traded, Crumbs small revenues, losses and rapidly shrinking equity made it economically meaningless. But, it is receiving a lot of attention because this minor event signals to many people the end of the “cupcake trend” which apparently was started by cable TV show “Sex and the City.”

However, there are actually 2 very important lessons all of us can learn from the rise, and fall, of Crumbs Bake Shop:

1 – Don’t believe in the myth of passion when it comes to business

Many management gurus, and entrepreneurs, will tell you to go into business following something about which you are passionate. The theory goes that if you have passion you will be very committed to success, and you will find your way to success with diligence, perseverance, hard work and insight driven by your passion. Passion will lead to excellence, which will lead to success.

And this is hogwash.

Customers don’t care about your passion. Customers care about their needs. Rather than being a benefit, passion is a negative because it will cause you to over-invest in your passion. You will “never say die” as you keep trying to make success out of an idea that has no chance. Rather than investing your resources into something that fulfills people’s needs, you are likely to invest in your passion until you burn through all your resources. Like Crumbs.

The founders of Crumbs had a passion for cupcakes. But, they had no way to control an onslaught of competitors who could make different variations of the product. All those competitors, whether isolated cupcake shops or cupcakes offered via kiosks or in other shops, meant Crumbs was in a very tough fight to maintain sales and make money. It’s not you (and your passion) that controls your business destiny. Nor is your customers. Rather, it is your competition.

When there are lots of competitors, all capable of matching your product, and of offering countless variations of your product, then it is unlikely you can sustain revenues – or profits. There are many industries where cutthroat competition means profits are fleeting, or downright elusive. Airlines come to mind. Magazines. And many retail segments. It doesn’t matter how much passion you have, when there are too many competitors it’s a lousy business.

2 – Trends really do matter

Cupcakes were a hot product for a while. And that’s great. But it wasn’t hard to imagine that the trend would shift, and cupcakes would be displaced by something else. Whatever profits you might have when you sit on a trend, those profits evaporate fast when the trend shifts and all competitors are fighting for sales in a declining market.

Remember Mrs. Field’s cookies? In the 1980s an attractive cook and her investment banker husband built a business on soft, chewy, warm cookies sold in malls and retail streets across America. It seemed nobody could get enough of those chocolate chip cookies.

But then, one day, we did. We’d collectively had enough cookies, and we simply quit buying them. Mrs. Fields (and other cookie brand) stores were rapidly replaced with pretzels and other foodstuffs.

Or look at Krispy Kreme donuts. In the 1990s people went crazy for them, often lining up at stores waiting for the neon sign to come on saying “hot donuts”. The company exploded into 400 stores as the stock flew like a kite. But then, in a very short time, people had enough donuts. There were a lot more donut shops than necessary, and Krispy Kreme went bankrupt.

So it wasn’t hard to predict that shifting food tastes would eventually put an end to cupcake sales growth. Yet, Crumbs really didn’t prepare for trends to change. Despite revenue and profit problems, the leadership did not admit that cupcake sales had peaked, the market was going to decline, competition would become even more intense and Crumbs would need to find another business if it was to survive.

Few trends move as fast as tastes in sweets. But, trends do affect all businesses. Once we bought cameras (and film,) but now we use phones – too bad for Kodak. Once we used copiers, now we use email – too bad for Xerox. Once we watched TV, now we download from Netflix or Amazon – too bad for NBC, ABC, CBS and Comcast. Once we went to stores, now we order on-line – too bad for Sears. Once we used PCs, now we use mobile devices – too bad for Microsoft. These trends did not affect these companies as fast as shifting tastes affected Crumbs, but the importance of understanding trends and preparing for change is a constant part of leadership.

So Crumbs Bake Shop failure was one which could have been avoided. Leadership needed to overcome its passion for cupcakes and taken a much larger look at customer needs to find alternative products. It wasn’t hard to identify that some diversification was going to be necessary. And that would have been much easier if they had put in place a system to track trends, observing (and admitting) that their “core” market was stalled and they needed to move into a new trend category.

by Adam Hartung | Apr 23, 2014 | Current Affairs, Leadership

Every quarter I have to be reminded that “earnings season” is again upon us. The ritual of public companies announcing their sales and profits from recent quarters that generates a lot of attention in the business press. And I always wonder why this is a big deal.

What really matters to investors, employees, customers and vendors is “what will your business be like next quarter, and year?” We really don’t much care about the past. What we really want to know is “what should we expect in the future?”

For example, two companies announce quarterly results. One has a Price/Earnings (P/E) multiple of 12.8 and a dividend yield of 2.05%. The other has a multiple of 13.0, and a yield of 3.05%. For both companies net earnings overall were pretty much flat, but Earnings Per Share (EPS) improved due to an aggressive stock repurchase program. Both companies say they have new products in the pipeline, but they conservatively estimate full year results for 2014 to be flat or maybe even declining.

Do you know enough to make a decision on whether to buy either stock? Both?

Truthfully, the two companies are Xerox and Apple. Now does it matter?

While both companies have similar results and forward looking statements, how you view that information is affected by your expectations for each company’s future. So, in other words, the actual results are pretty meaningless. They are interpreted through the lens of expectations, which controls your decision.

You can say Xerox has been irrelevant for years, and its products increasingly look unlikely to change its future course, so you are disheartened by results you see as unspectacular and likewise see no reason to own the stock. For Apple you could say the same thing, and bring up the growing competitor sales of Android-based products. Or, you might say that Apple is undervalued because you have great faith in the growth of mobile products sales and you believe new devices will spur Apple to even better results. Whatever your conclusion about the announced earnings, those conclusions are driven by your view of the future – not the actual results.

Another example. Two companies have billions in sales, and devote their discussion of company value to technology and the use of new technology to pioneer new markets. Both companies report they continue a string of losses, and have no projection for when losses will become profits. There are no dividends. There is no P/E multiple, because there is no E. There is no EPS, again because there is no E. One company is losing $12.86/share, the other is losing $.61/share. Again, do these results tell you whether to buy either, one or both?

What if the first one (with the larger losses) is Sears Holdings, and the latter is Tesla? Now, suddenly your view on the data changes – based upon your view of the future. Either Sears is on the precipice of a turnaround to becoming a major on-line retailer that will sell some real estate and leverage the balance of its stores to grow, so you buy it, or you think Sears has lost all relevancy and you don’t buy it. Either you think Tesla is an industry game changer, so you buy it, or you think it is an over-rated fad that will never become big enough to matter and the giant global auto companies will destroy it, so you don’t buy it. It’s your future view that guides your conclusions about past results.

The critical factor when reviewing earnings is actually not the reported results. The critical factor is what you think the future is for these 4 companies. No matter how good or bad the historical results, your decision about whether to own the stock, buy the company products, work for the company or join its vendor program all hinges on your view about the company’s future.

Which makes not only the “earnings season” hoopla foolish, but puts a pronounced question mark on how executives – especially CEOs – in public companies spend their time as it relates to reporting results.

Enormous energy is spent by most CEOs and their staff on managing earnings. From the beginning to the end of every quarter the CFO and his/her staff pour over weekly outcomes in divisions and functions to understand revenues and costs in order to gain advance knowledge on likely results. Then, for the next several days/weeks the CFO’s staff, with the CEO and the leadership team, will pour over those results to make a myriad number of adjustments – from depreciation and amortization to deferring revenue changing tax structures or time-matching various costs – in order to further refine the reported results. Literally thousands of person-hours will be devoted to managing the reported results in order to provide the number they think is most appropriate. And this cycle is repeated every quarter.

But how many hours will be spent by that same CEO and the leadership team managing expectations about the company’s next year? How much time do these leaders spend developing scenarios, and communications, that will describe their vision, in order to manage investor expectations?

While every company has a CFO leading a large organization dedicated to reporting historical results, how many companies have a like-powered C level exec managing the expectations, and leading a large staff to create and deliver communications about the future?

It seems pretty clear that most management teams should consider reallocating their precious resources. Instead of spending so much time managing earnings, they should spend more time managing expectations. If we think about the difference between Xerox and Apple, one is quickly aware of the difference the CEOs made in setting expectations. People still wax eloquently about the future vision for Apple created by CEO Steve Jobs, who’s been dead 2.5 years, while almost no one can tell you the name of Xerox’ CEO. If you think about the difference between Sears and Tesla one only needs to think briefly about the difference between the numbers driven hedge fund manager and cost-cutting CEO Ed Lampert compared with the “visionary” communications of Elon Musk.

Investors should all think long term. Investors should care completely about what the next 3 to 5 years will mean for companies in which they place their money. What sales and earnings are reported from months ago is pretty meaningless. What really matters is what is yet to happen.

What we don’t need is a lot of time spent talking about old earnings. What we need is a lot more time spent talking about the future, and what we should expect from our investments.

by Adam Hartung | Oct 4, 2011 | Current Affairs, Defend & Extend, Film, In the Rapids, Innovation, Leadership, Television, Transparency, Web/Tech

Reed Hastings, the CEO of Netflix, has long been considered a pretty good CEO. In January, 2009 his approval ranking, from Glassdoor, was an astounding 93%. In January, 2010 he was still on the top 25 list, with a 75% approval rating. And it's not surprising, given that he had happy employees, happy customers, and with Netflix's successful trashing of Blockbuster the company's stock had risen dramaticall,y leading to very happy investors.

But that was before Mr. Hastings made a series of changes in July and September. First Netflix raised the price on DVD rentals, and on packages that had DVD rentals and streaming download, by about $$6/month. Not a big increase in dollar terms, but it was a 60% jump, and it caught a lot of media attention (New York Times article). Many customers were seriously upset, and in September Netflix let investors know it had lost about 4% of its streaming subscribers, and possibly as many as 5% of its DVD subscribers (Daily Mail).

No investor wants that kind of customer news from a growth company, and the stock price went into a nosedive. The decline was augmented when the CEO announced Netflix was splitting into 2 companies. Netflix would focus on streaming video, and Quikster would focus on DVDs. Nobody understood the price changes – or why the company split – and investors quickly concluded Netflix was a company out of control and likely to flame out, ruined by its own tactics in competition with Amazon, et.al.

(Source: Yahoo Finance 3 October, 2011)

(Source: Yahoo Finance 3 October, 2011)

This has to be about the worst company communication disaster by a market leader in a very, very long time. TVWeek.com said Netflix, and Reed Hastings, exhibited the most self-destructive behavior in 2011 – beyond even the Charlie Sheen fiasco! With everything going its way, why, oh why, did the company raise prices and split? Not even the vaunted New York Times could figure it out.

But let's take a moment to compare Netflix with another company having recent valuation troubles – Kodak.

Kodak invented home photography, leading it to tremendous wealth as amature film sales soared for seveal decades. But last week Kodak announced it was about out of cash, and was reaching into its revolving credit line for some $160million to pay bills. This latest financial machination reinforced to investors that film sales aren't what they used to be, and Kodak is in big trouble – possibly facing bankruptcy. Kodak's stock is down some 80% this year, from $6 to $1 – and quite a decline from the near $80 price it had in the late 1990s.

(Source: Yahoo Finance 10-3-2011)

Why Kodak declined was well described in Forbes. Despite its cash flow and company strengths, Kodak never succeeded beyond its original camera film business. Heck, Kodak invented digital photography, but licensed the technology to others as it rabidly pursued defending film sales. Because Kodak couldn't adapt to the market shift, it now is probably going to fail.

And that is why it is worth revisiting Netflix. Although things were poorly explained, and certainly customers were not handled well, last quarter's events are the right move for investors in the shifting at-home video entertainment business:

- DVD sales are going the direction of CD's and audio cassettes. Meaning down. It is important Netflix reap the maximum value out of its strong DVD position in order to fund growth in new markets. For the market leader to raise prices in low growth markets in order to maximize value is a classic strategic step. Netflix should be lauded for taking action to maximize value, rather than trying to defend and extend a business that will most likely disappear faster than any of us anticipate – especially as smart TVs come along.

- It is in Netflix's best interest to promote customer transition to streaming. Netflix is the current leader in streaming, and the profits are better there. Raising DVD prices helps promote customer shifting to the new technology, and is good for Netflix as long as customers don't change to a competitor.

- Although Netflix is currently the leader in streaming it has serious competition from Hulu, Amazon, Apple and others. It needs to build up its customer base rapidly, before people go to competitors, and it needs to fund its streaming business in order to obtain more content. Not only to negotiate with more movie and TV suppliers, but to keep funding its exclusive content like the new Lillyhammer series (more at GigaOm.com). Content is critical to maintaining leadership, and that requires both customers and cash.

- Netflix cannot afford to muddy up its streaming strategy by trying to defend, and protect, its DVD business. Splitting the two businesses allows leaders of each to undertake strategies to maximize sales and profits. Quikster will be able to fight Wal-Mart and Redbox as hard as possible, and Netflix can focus attention on growing streaming. Again, this is a great strategic move to make sure Netflix transitions from its old DVD business into streaming, and doesn't end up like an accelerated Kodak story.

Historically, companies that don't shift with markets end up in big trouble. AB Dick and Multigraphics owned small offset printing, but were crushed when Xerox brought out xerography. Then, afater inventing desktop publishing at Xerox PARC, Xerox was crushed by the market shift from copiers to desktop printers – a shift Xerox created. Pan Am, now receiving attention due to the much hyped TV series launch, failed when it could not make the shift to deregulation. Digital Equipment could not make the shift to PCs. Kodak missed the shift from film to digital. Most failed companies are the result of management's inability to transition with a market shift. Trying to defend and extend the old marketplace is guaranteed to fail.

Today markets shift incredibly fast. The actions at Netflix were explained poorly, and perhaps taken so fast and early that leadership's intentions were hard for anyone to understand. The resulting market cap decline is an unmitigated disaster, and the CEO should be ashamed of his performance. Yet, the actions taken were necessary – and probably the smartest moves Netflix could take to position itself for long-term success.

Perhaps Netflix will fall further. Short-term price predictions are a suckers game. But for long-term investors, now that the value has cratered, give Netflix strong consideration. It is still the leader in DVD and streaming. It has an enormous customer base, and looks like the exodus has stopped. It is now well organized to compete effectively, and seek maximum future growth and value. With a better PR firm, good advertising and ongoing content enhancements Netflix has the opportunity to pull out of this communication nightmare and produce stellar returns.

In a bit of “get them the razor so they will buy the razor blades” CEO Tim Cook’s Apple is increasingly relying upon farming the “installed base” of users to drive additional revenues. Leveraging the “installed base” of users is now THE primary theme for growing Apple sales. And even old-tech guys like Warren Buffett at Berkshire Hathaway love it, as they gobble up Apple shares. As do many analysts, and investors. Apple has paid out over $100B to developers for its services, and generated over $40B in revenues for itself – and with such a large base willing to buy things developers are likely to keep providing more products and working to grow sales.

In a bit of “get them the razor so they will buy the razor blades” CEO Tim Cook’s Apple is increasingly relying upon farming the “installed base” of users to drive additional revenues. Leveraging the “installed base” of users is now THE primary theme for growing Apple sales. And even old-tech guys like Warren Buffett at Berkshire Hathaway love it, as they gobble up Apple shares. As do many analysts, and investors. Apple has paid out over $100B to developers for its services, and generated over $40B in revenues for itself – and with such a large base willing to buy things developers are likely to keep providing more products and working to grow sales.