by Adam Hartung | Oct 21, 2016 | Boards of Directors, Finance, Investing

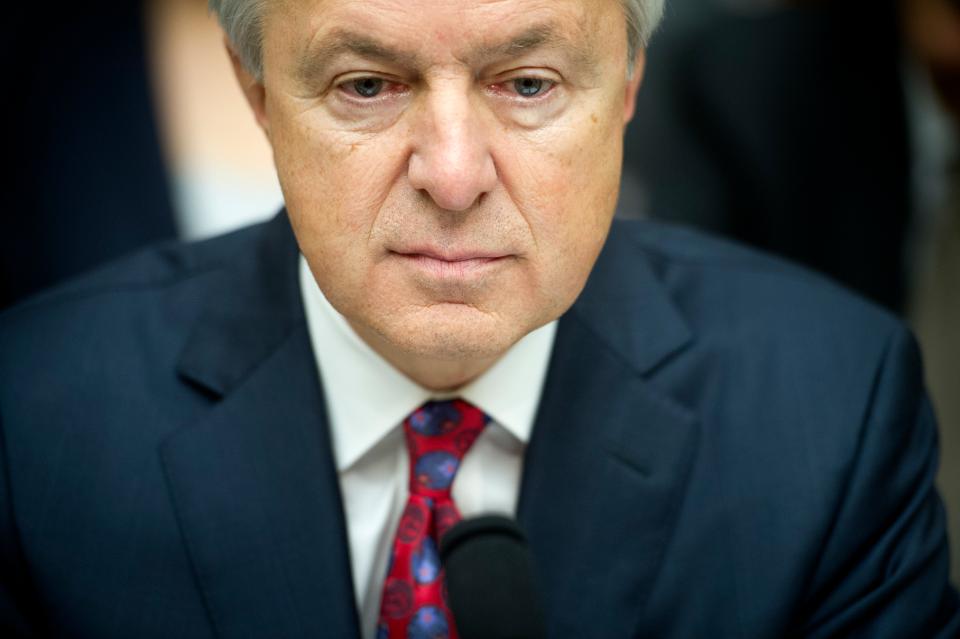

(AP Photo/Cliff Owen, File)

Wells Fargo’s CEO John Stumpf resigned last week. This week he also resigned from the boards of directors at Chevron and Target. For those two roles he was being paid something like $650,000 per year. The interesting question is, why was he on those boards at all? Wasn’t being the CEO and on the board at one of America’s biggest banks a full-time job? After all, he was paid $19.3 million in both 2015 and 2014. You would not have thought he needed a side job to make ends meet.

Which leads to the question, are America’s boards of directors actually staffed with the right people? Ostensibly the board is responsible for governing the corporation. Directors are responsible to insure management makes the right decisions for the long-term best interests of shareholders. And legislators’ have passed multiple laws, such as Sarbanes-Oxley and Dodd-Frank, to allow the regulators, primarily at the SEC (Securities and Exchange Commission), to put real teeth (and enforcement) into directors’ responsibilities.

According to the National Association of Corporate Directors (NACD) a sitting director should do a minimum of 200 hours of work on a board every year. For larger companies committee requirements on top of general board work could easily push this to nearly 300 hours. Thus, Mr. Stumpf should have been doing at least 500 hours of work for Chevron and Target – about 12.5 weeks, or three months. Do you think he actually spent this much time on these roles, given his full time job at Wells Fargo?

This also means that Mr. Stumpf only had nine months to actually work as CEO of Wells Fargo. Maybe that was why he was so unaware of the unethical behavior at the company he led? Why would a board think it is acceptable for a CEO to work only three-fourths of the year? Not many employees have the opportunity to draw full compensation yet take off so much time.

Either Mr. Stumpf wasn’t paying enough attention to Wells Fargo, or he wasn’t paying enough attention to Chevron and Target. Yet, he was being paid very, very handsomely for all those roles. How is that good governance for any one of the three companies?

CEOs serving on additional boards is a bit like electing a governor, who is paid to run the state, and then hearing that the governor is simultaneously going to do part time work for a company or perhaps an agency of a different state. Would any state accept that their governor, state CEO, be allowed to spend three months of every year working side jobs that have nothing to do with being governor? Yet, corporate CEOs regularly take on director roles for other corporations – which in no way benefits their company’s employees, or shareholders. Why?

Further, boards are dominated by sitting or former CEOs. Why? The world moves fast toda, and there are a wealth of skills boards need to effectively govern – far beyond having a room full of CEOs. IT skills, cyber security skills, social media skills, marketing and advertising skills, branding skills, global market skills, intellectual property skills – there is a long list of skills which would greatly improve board diversity, and thereby a board’s ability to govern effectively. So why is hiring so biased toward CEOs? NACD has been asking the same question as it promotes diversity in the boardroom.

Yet, there is one group that is making hay with all that board pay. Former regulators and members of Congress. These people are required to register if they become lobbyists, and they are forced to wait a year, or more, before they can do work for government contractors. But there is nothing which stops them from joining a board of directors.

There is nothing about being a Congressman or Senator which prepares these people for corporate governance, yet this is common practice as corporations seek ways to find influence without breaking the law. But is it worthwhile to investors to have directors that were prominent in government, but perhaps lacking competency for today’s fast-paced business world? Should a directorship and the compensation be a reward for previous government work – or should it be a position of great importance looking out for the interest of the corporation?

There are currently 64 former members of Congress serving on corporate boards. According to a Harvard and Boston University study, 44% of Senators, and 11% of Congress members have landed corporate board directorships since 1992. Their average compensation, per board, is $350,000. Much better than being in Congress. Especially for a part-time job.

Former Speaker John Boehner and famous cigarette smoker, just joined the tobacco company Reynolds America board – although that may be short-lived as British American Tobacco has offered to acquire Reynolds. Former Majority leader Eric Cantor, who was up for the Speaker job when losing his last election, is now on the board of a Wall Street firm, where he earned $2 million in 2015 for bringing in new business – making him the highest paid director in this group. Former Majority Leader Dick Gephardt has accumulated $10.8 million in director compensation since retiring from Congress in 2005.

Tom Ridge, who was a governor, house member and secretary of Homeland Security – but never a businessperson – raked in $1.4 million in director compensation last year. Even former Congressman and subsequently Secretary of Defense and director of the CIA Leon Panetta made almost $600,000 in director comp last year. These fellows are obviously well connected to government leaders, but do they have a clue about how to effectively implement regulations for corporate audit, compensation or nominating and governance committee roles? Are they hired to apply good governance for investors, or to be rainmakers for the company? Or just to give them a good retirement plan?

Boards exist to protect the rights of shareholders. But do they? The issues at Wells Fargo are an example of how ineffective a board can be at oversight, given that serious problems lasted there for at least five years, and whistle-blowers were terminated for specious reasons. And the Wells board paid the CEO almost $20 million per year, while letting him work a quarter or more of each year as a director for other companies. Hard to see how those directors were doing their job.

When companies do poorly employees, investors and analysts will ask “where was the board?” Increasingly it is clear that more should be asking “who is on the board?” Boards should not be stacked with folks that have lofty titles from previous positions, but which are irrelevant to the needs of that corporation and frequently lacking the qualifications to govern effectively. Target’s investors, for example, probably would have benefited far more by a director that understood networks and cyber crime than paying Mr. Stumpf for his part-time assistance away from Wells Fargo. And with oil prices at generational lows, how did Mr. Stumpf help Chevron prepare for a new world of lower oil demand and greater supplier anxiety in the Middle East?

Sarbanes-Oxley was passed after the outrage that occurred at Enron, where the company completely failed and yet the board said it had no idea of the company’s problems. When America’s financial services industry nearly melted down Dodd-Frank was passed to put more onus on directors to understand the financials and compensation practices of their companies. But, it will most likely take yet more legislation, and more regulation, if investors are to be protected by truly independent directors that are the right people, in the right job, and feel accountable for management oversight and company outcomes.

by Adam Hartung | Oct 13, 2016 | Boards of Directors, Ethics, Finance, Investing, Leadership

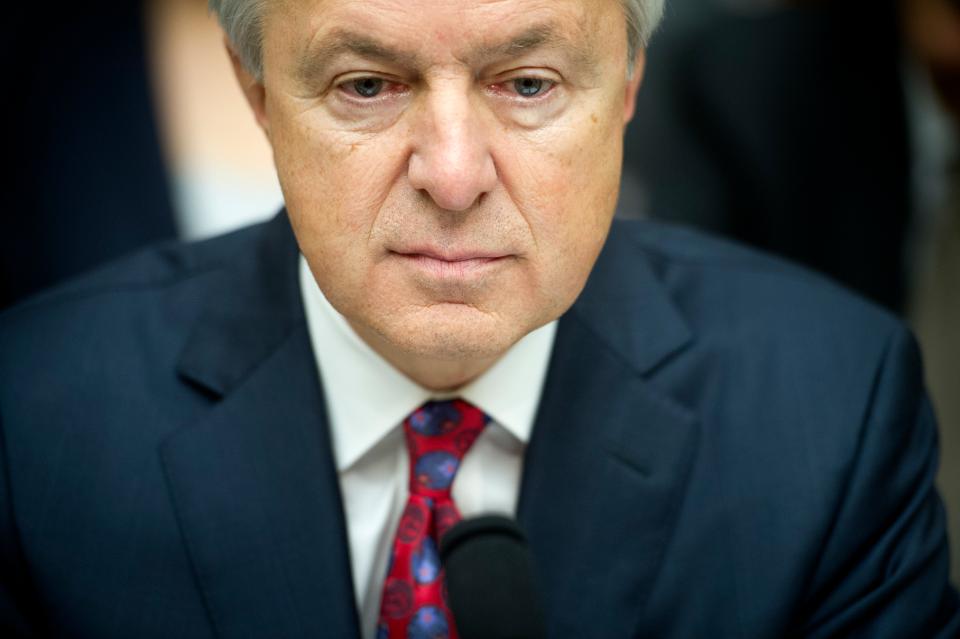

SAUL LOEB/AFP/Getty Images

Everyone knows what happened at Wells Fargo. For many years, possibly as far back as 2005, Wells Fargo leaders pushed employees to “cross-sell” products, like high profit credit cards, to customers. Eventually the company bragged it had an industry leading 6.7 products sold to every customer household. However, we now know that some two million of these accounts were fakes – created by employees to meet aggressive sales goals. And, unfortunately, costing unsuspecting customers quite a lot of fees.

We also know that Wells Fargo leadership knew about this practice for at least five years – and agreed to a $190 million fine. And the company apparently fired 5,300

Which begs the obvious question – if management knew this was happening, why did it continue for at least five years?

Let’s face it, if you owned a restaurant and you knew waiters were adding extras onto the bill, or tip, you would not only fire those waiters, but put in place procedures to stop the practice. But in this case we know that management at Wells Fargo was receiving big bonuses based upon this employee behavior. So they allowed it to continue, perhaps with a gloss of disdain, in order for the execs to make more money.

This is the modern, high-tech financial services industry version of putting employees in known dangerous jobs, like picking coal, in order to make more profit. A lot less bloody, for sure, but no less condemnable. Management was pushing employees to skirt the law, while wearing a fig-leaf of protection.

Ignorance is not excuse – especially for a well-paid CEO.

CEO Stumpf’s testified to Congress that he didn’t know the details of what was happening at the lower levels of his bank. He didn’t know bankers were expected to make 100 sales calls per day. When asked about how sales goals were implemented, he responded to Representative Keith Ellison “Congressman, I don’t know that level of detail.”

Really? Sounds amazingly like Bernie Ebbers at Worldcom. Or Jeff Skilling and Ken Lay at Enron. Men making millions of dollars from illegal activities, but claiming they were ignorant of what their own companies were doing. And if they didn’t know, there was no way the board of directors could know, so don’t blame them either.

Does anyone remember how Congress reacted to those please of ignorance? “No more.” Quickly the Sarbanes-Oxley act was passed, making not only top executives but Boards, and in particular audit chairs, responsible for knowing what happened in their companies. And later Dodd-Frank was passed strengthening these laws – particularly for financial services companies. Ignorance would no longer be an excuse.

Where was Wells Fargo’s compliance department?

Based on these laws every Board of Directors is required to establish a compliance officer to make sure procedures are in place to insure proper behavior by management. This compliance officer is required to report to the board that procedures exist, and that there are metrics in place to make sure laws, and ethics policies, are followed.

Additionally, every company is required to implement a whistle-blower hotline so that employees can report violations of laws, regulations, or company policies. These reports are to go either to the audit chair, or the company external legal counsel. If it is a small company, possibly the company general counsel who is bound by law to keep reports confidential, and report to the board. This was implemented, as law, to make sure employees who observed illegal and unethical management behavior, as happened at Worldcom, Enron and Tyco, could report on management and inform the board so Directors could take corrective action.

Which begs the first question “where the heck was Wells Fargo’s compliance office the last five years?” These were not one-off events. They were standard practice at Wells Fargo. Any competent Chief Compliance Officer had to know, after five-plus years of firings, that the practices violated multiple banking practice laws. He must have informed the CEO. He was, by law, supposed to inform the board. Who was the Chief Compliance Officer? What did he report? To whom? When? Why wasn’t action taken, by the board and CEO, to stop these banking practices?

Should regulators allow executives to fire whistle-blowers?

And about that whistle-blower hotline – apparently employees took advantage of it. In 2010, 2011, 2013 and more recently employees called the hotline, even wrote the Human Resources Department and the office of CEO John Stumpf to report unethical practices. Were their warnings held in anonymity? Were they rewarded for coming forward?

Quite to the contrary, one employee, eight days after logging a hotline call, was fired for tardiness. Another was fired days after sending an email to CEO Stumpf alerting him of aberrant, unethical practices. A Wells Fargo HR employee confirmed that it was common practice to find fault with employees who complained, and fire them. Employees who learned from Enron, and tried to do the right thing, were harassed and fired. Exactly 180 degrees contrary to what Congress ordered when passing recent laws.

None of this was a mystery to Wells Fargo leadership, or CEO Stumpf. CNNMoney reported the names of employees, actions they took and the decisively negative reactions taken by Wells Fargo on September 21. There is no way the Wells Fargo folks who prepared CEO Stumpf for his September 29 testimony were unaware. Yet, he replied to questions from Congress that he didn’t know, or didn’t remember, these events – or these people. In eight days these staffers could have unearthed any information – if it had been exculpatory. That Stumpf’s answer was another plea of ignorance only points to leadership’s plan of hiding behind fig leafs.

CEO Stumpf obviously knew the practices at Wells Fargo. So did all his direct reports. And likely two or three levels downs, at a minimum. Clearly, all the way to branch managers. Additionally, the compliance function was surely fully aware, as was HR, of these practices and chose not to solve the issues – but rather hide them and fire employees in an effort to eliminate credible witnesses from reporting wrongdoing by top leadership.

Where was the board of directors? Why didn’t the audit chair intervene?

It is the explicit job of the audit chair to know that the company is in compliance with all applicable laws. It is the audit chairs’ job to implement the Sarbanes-Oxley and Dodd-Frank regulations, and report any variations from regulations to the company auditors, general counsel, lead outside director and chairperson. Where was proper governance of Wells Fargo? Were the Directors doing their jobs, as required by law, in the post Enron, WorldCom, Tyco, Lehman, AIG world?

Should CEO Stumpf be gone? Without a doubt. He should have been gone years ago, for failing to properly implement and enforce compliance. But he is not alone. The officers who condoned these behaviors should also be gone, as should all HR and other managers who failed to implement the regulations as Congress intended.

Additionally, the board of Wells Fargo has plenty of responsibility to shoulder. The board was not effective, and did not do its job. The directors, who were well paid, did not do enough to recognize improper behavior, implement and monitor compliance or take action.

There is a lot more blame here, and if Wells Fargo is to regain the public trust there need to be many more changes in leadership, and Board composition. It is time for the SEC to dig much deeper into the situation at Wells Fargo, and the leaders complicit in failing to follow the intent of Congress.

by Adam Hartung | Jan 15, 2014 | Current Affairs, Leadership

The S&P 500 had a great 2013. Up 29.7% – its best performance since 1997. The Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA) ended the year up 26.5% – its best performance since 1995. And this happened as economic growth lowered the unemployment rate to 6.7% in December – the lowest rate in 5 years. And overall real estate had double-digit price gains, lowering significantly the number of underwater mortgages.

But if we go back to the beginning of 2013, most Wall Street forecasters were predicting a very different outcome. Long suffering bear Harry Dent predicted a stock crash in 2013 that would last through 2014, and ongoing cratering in real estate values. And bear Gina Martin Adams of Wells Fargo Securities predicted a market decline in 2013, a forecast she clung to and fully supported, despite a rising market, when predicting an imminent crash in September. Morgan Stanley’s Adam Parker also predicted a flat market, as did UBS analyst Jonathan Golub.

How could professionals who are paid so much money, have so many resources and the backing of such outstanding large and qualified institutions be so wrong?

An over-reliance on quantitative analysis, combined with using the wrong assumptions.

The conventional approach to Wall Street forecasting is to use computers to amass enormously complex spreadsheets combining reams of numbers. Computer models are built with thousands of inputs, and tens of millions of data points. Eventually the analysts start to believe that the sheer size of the models gives them validity. In the analytical equivalent of “mine is bigger than yours” the forecasters rely on their model’s complexity and sheer size to self-validate their output and forecasts.

In the end these analysts come up with specific forecast numbers for interest rates, earnings, momentum indicators and multiples (price/earnings being key.) Their faith that the economy and market can be reduced to numbers on spreadsheets leads them to similar faith in their forecasts.

But, numbers are often the route to failure. In the late 1990s a team of Wall Street traders and Nobel economists became convinced their ability to model the economy and markets gave them a distinct investing advantage. They raised $1billion and formed Long Term Capital (LTC) to invest using their complex models. Things worked well for 3 years, and faith in their models grew as they kept investing greater amounts.

But then in 1998 downdrafts in Asian and Russian markets led to a domino impact which cost Long Term Capital $4.6B in losses in just 4 months. LTC lost every dime it ever raised, or made. But worse, the losses were so staggering that LTC’s failure threatened the viability of America’s financial system. The banks, and economy, were saved only after the Federal Reserve led a bailout financed by 14 of the leading financial institutions of the time.

Incorrect assumptions played a major part in how Wall Street missed the market prediction for 2013. All models are based on assumptions. And, as Peter Drucker famously said, “if you get the assumptions wrong everything you do thereafter will be wrong as well” — regardless how complex and vast the models.

Conventional wisdom held that conservative economic policies underpin market growth, and the more liberal Democratic fiscal policies combined with a liberal federal reserve monetary program would bode poorly for investors and the economy in 2013. These deeply held assumptions were, of course, reinforced by a slew of conservative commentators that supported the notion that America was on the brink of runaway inflation and economic collapse. The BIAS (Beliefs, Interpretations, Assumptions and Strategies) of the forecasters found reinforcement almost daily from the rhetoric on CNBC, Bloomberg, Fox News and other programs widely watched by business people from Wall Street to Main Street.

Interestingly, when Obama was re-elected in 2012 a not-so-well-known investment firm in Columbus, OH – far from Wall Street – took an alternative look at the data when forecasting 2013. Polaris Financial Partners took a deep dive into the history of how markets perform when led by traditional conservative vs. liberal policies and reached the startling conclusion that Obama’s programs, including the Affordable Care Act, would actually spur investment, market growth, jobs and real estate! They had forecast a double digit increase in all major averages for 2012 and extended that same double digit forecast into 2013 – far more optimistic than anyone on Wall Street.

CEO Bob Deitrick and partner Steven Morgan concluded that the millenium’s first decade had been lost. Despite Republican leadership, the eqity markets were, at best, sideways. There were fewer people actually working in 2008 than in 2000; a net decrease in jobs. After a near-collapse in the banking system, due to deregulated computer-model based trading in complex derivatives, real estate and equity prices had collapsed.

“Fourteen years of stock market gains were wiped out in 17 months from October, 2007 to March, 2009” lamented Deitrick.

Polaris Partners concluded the situation was eerily similar to the 1920s at the end of Hoover’s administration. A situation which was eventually resolved via Keynesian policies of increased fiscal spending while interest rates were low, and federal reserve intervention to both expand the money supply and increase the velocity of money under Republican Fed chief Marriner Eccles and Democratic President Franklin Roosevelt.

While most people conventionally think that tax cuts led to economic growth during the Reagan administration, Polaris Financial turned that assumption upside down and put the biggest positive economic impact on the roll-back of tax cuts a year after being pushed by Reagan and passing Congress. Their analysis of the 1980 recovery focused on higher defense and infrastructure spending (fiscal policy,) a massive increase in debt (the largest peacetime debt increase ever) coupled with a more balanced tax code post-TEFRA.

Thus, eschewing complex econometric models, elaborately detailed spreadsheets of earnings and rolling momentum indicators, Polaris Financial focused instead on identifying the assumptions they believeed would most likely drive the economy and markets in 2013. They focused on the continuation of Chairman Bernanke’s easy monetary policy, and long-term fiscal policies designed to funnel money into investments which would incent job creation and GDP growth leading to an improvement in house values, and consumer spending, while keeping interest rates at historically low levels. All of which would bode extremely well for thriving equity markets.

The vitriol has been high amongst those who support, and those who oppose, the economic policies of Obama’s administration since 2008. But vitriol does not support, nor replace, good forecasting. Too often forecasters predict what they want to happen, what they hope will happen, based upon their view of history, their traing and background, and their embedded assumptions. They believe in the certainty of long-held assumptions, and forecast from that base.

But as Polaris Financial pointed out, in beating every major Wall Street firm over the last 2 years, good forecasting relies on looking carefully at historical outcomes, and understanding the context in which those results happened. Rather than relying on an interpretation of the outcome,they looked instead at the facts and the situation; the actions and the outcomes in its context. In an economy, everything is relative to the context. There are no absolute programs that are universally the right thing to do. Every policy action, and every monetary action, is dependent upon initial conditions as well as the action itself.

Too few forecasters take into account both the context as well as the action. And far too few do enough analysis of assumptions, preferring instead to rely on reams of numerical analysis which may, or may not, relate to the current situation. And are often linked to assumptions underlying the model’s construction – assumptions which could be out of date or simply wrong.

The folks at Polaris Financial Partners remain optimistic about the economy and markets for the next two years. They point out that unemployment has dropped faster under Obama, and from a much higher level, than during the Reagan administration. They see the Affordable Care Act opening more flexibility for health care, creating a rise in entrepreneurship and innovation (especially biotechnology) that will spur economic growth. Deitrick and Morgan see tax programs, and rising minimum wage trends, working toward better income balancing, and greater monetary velocity aiding GDP growth. Their projection is for improving real estate values, jobs growth, and minimal inflation leading to higher indexes – such as 20,000 on the DJIA and 2150 on the S&P.

Bob Deitrick co-authored, with Lew Goldfarb, “Bulls, Bears and the Ballot Box” in 2012 analyzing Presidential economic policies, Federal Reserve policies and stock market performance.

by Adam Hartung | Dec 19, 2013 | Current Affairs, Leadership

Everyone has a stake in America’s big, public corporations. Either as an investor, employee, customer, supplier or community leader. So how these corporations perform is a big deal for all of us.

Unfortunately, we’ve had all too many corporations that have their problems. But, amazingly, we see little change in the CEO, or CEO compensation. When one of the USA‘s largest employers, McDonald’s, uses its hotline to tell low-paid employees they should avoid breaking open Christmas gift boxes, and instead return gifts for cash to buy gas and groceries, it’s not a bad idea to take a look at top executive pay. And with so many people still looking for work, and unemployment for people under 25 at something like 15%, there is an ongoing question as to whether CEOs are being held accountable or simply granted their jobs regardless of performance.

Given that Scrooge was a banker, why not start by looking at bank CEOs? And who better to glance at than the ultra-high profile Jamie Dimon, CEO and Chairman of JPMorganChase.

In 2012 Mr. Dimon told us there were really no problems in the JPMC derivatives business. We later learned that – oops – the unit did actually lose something like $6billion. Mr. Dimon was nice enough to admit this was more than a “templest in a teapot,” and eventually apoligized. He asked us to all realize that JPMC is really big, and mistakes will happen. Just forget about it and move on he recommended.

But in 2013 the regulators said “not so fast” and fined JPMC close to $1billion for failure to properly safeguard the public interest. The Board felt compelled to reflect on this misadventure and cut Mr. Dimon’s pay in half to a paltry $18.7million. That means in the year when things went $7billion wrong, he was paid nearly $37million – and the penalty was to subsequently receive only $19million. Thus his total compensation for 2 years, during which $7billion evaporated from the bank, was (roughly) $50M.

It appears unlikely anyone will be returning gifts to buy ham and beans in the Dimon household this year.

Mr. Dimon was spanked by the Board, and he is no longer the most highly paid CEO in the banking industry. That 2013 title goes to Wells Fargo CEO John Stumpf, who received about $23M. Wells Fargo is still sorting out the mess from all those bad mortgages which have left millions of Americans with foreclosures, bankruptcies, costly short-sales and mortgages greater than the home value. But, hotlines are now in place and things are getting better!

CEO compensation is interesting because it is all relative. Pay is minimally salary – never more than $1M (although that alone is a really big number to most people.) Bonuses make up most of the compensation,based on relative metrics tied to comparisons with industry peers. So, if an industry does badly and every company does poorly the CEOs still get paid their bonuses. You don’t have to be a Steve Jobs or Jeff Bezos with new insights, lots of growth, great products and margins to be paid a lot. Just don’t do a whole lot worse than some peer group you are compared against.

Which then brings us to the whole idea of why CEOs that make big mistakes – like the whopper at JPMC – so easily keep their jobs. Would a McDonald’s cashier that missed handing out change by $7 (1 one-billionth the JPMC mistake) likely be paid well – or fired? What about a JPMC bank teller? Yet, even when things go terribly wrong we rarely see a CEO lose their job.

During this shopping season, just look at Sears. Ed Lampert cut his pay to $1 in 2013. Hooray! But this did not help the company.

Sears and Kmart business is so bad CEO Lampert changed strategy in 2013 to selling profitable stores rather than more lawn mowers and hand tools in order to keep the company alive. Yet, as more employees leave, suppliers risk being repaid, communities lose their stores and retail jobs and tax base, Mr. Lampert remains Sears Holdings CEO. We accept that because he owns so much stock he has the “right” to remain CEO.

Perhaps Mr. Lampert deserves a visit from his own personal Jacob Marley, who might make him realize that there is more to life (and business) than counting cash flow and seeking lower cost financing options. Mr. Lampert can arise each morning before dawn to browbeat employees via conference webinars, and micromanage a losing business. But it leaves him sounding a lot like Scrooge. Meanwhile those behaviors have not stopped Sears and KMart from losing all market relevancy, and spiraling toward failure.

CEO pay-to-worker ratios have increased 1,000% since 1950. (How’s that for a “relative” metric?) Today the average CEO makes 200 times the company’s workforce (the top 100 make 300 times as much – and the CEO of Wal-Mart has a pension 6,182 times that of the average employee.) Is it any wonder so many investors, employees, customers, suppliers and community leaders are paying so much attention to CEO performance – and pay?

We are all thankful for the good CEO that develops long-range plans, spends time investing in growth projects, developing employees, increasing revenue and margins while expanding the communities in which the company lives and works. It just doesn’t happen often enough.

This Christmas, as many before, as we look at our portfolios, paychecks, pensions, product quality, service quality and communities too many of us wish far too often for better CEOs, and compensation really aligned with long-term performance for all constituencies.

by Adam Hartung | May 7, 2009 | Current Affairs, Defend & Extend, In the Swamp, Leadership, Lock-in

Good public policy and good management don't always align. And the banking crisis is a good example. We now hear "Banks must raise $75billion" if they are to be prepared for ongoing write-downs in a struggling economy. This is after all the billions already loaned to keep them afloat the last year.

But the bankers are claiming they will have no problem raising this money as reported in "The rush to raise Capital." "AIG narrows loss" tells how one of the primary contributors to the banking crisis now thinks it will survive. And as a result of this news, "Bank shares largely higher" is another headline reporting how financial stocks surged today post-announcements.

So regulators are feeling better. They won't have to pony up as much money as they might have. And politicians feel better, hoping that the bank crisis is over. And a lot of businesses feel better, hearing that the banks which they've long worked with, and are important to their operations, won't be going under. Generally, this is all considered good news. Especially for those worried about how a soft economy was teetering on the brink of getting even worse.

But the problem is we've just extended the life of some pretty seriously ill patients that will probably continue their bad practices. The bail out probably saved America, and the world, from an economic calamity that would have pushed millions more into unemployment and exacerbated falling asset values. A global "Great Depression II" would have plunged millions of working poor into horrible circumstances, and dramatically damaged the ability of many blue and white collar workers in developed countries to maintain their homes. It would have been a calamity.

But this all happened because of bad practices on the part of most of these financial institutions. They pushed their Success Formulas beyond their capabilities, causing failure. Only because of the bailout were these organizations, and their unhealthy Success Formulas saved. And that sows the seeds of the next problem. In evolution, when your Success Formula fails due to an environomental shift you are wiped out. To be replaced by a stronger, more adaptable and better suited competitor. Thus, evolution allows those who are best suited to thrive while weeding out the less well suited. But, the bailout just kept a set of very weak competitors alive – disallowing a change to stronger and better competitors.

These bailed out banks will continue forward mostly as they behaved in the past. And thus we can expect them to continue to do poorly at servicing "main street" while trying to create risk pass through products that largely create fees rather than economic growth. These banks that led the economic plunge are now repositioned to be ongoing leaders. Which almost assures a continuing weak economy. Newly "saved" from failure, they will Defend & Extend their old Success Formula in the name of "conservative management" when in fact they will perpetuate the behavior that put money into the wrong places and kept money from where it would be most productive.

Free market economists have long discussed how markets have no "brakes". They move to excess before violently reacting. Like a swing that goes all one direction until violently turning the opposite direction. Leaving those at the top and bottom with very upset stomachs and dramatic vertigo. The only way to avert the excessive tops is market intervention – which is what the government bail-out was. It intervened in a process that would have wiped out most of the largest U.S. banks. But, in the wake of that intervention we're left with, well, those same U.S. banks. And mostly the same leaders.

What's needed now are Disruptions inside these banks which will force a change in their Success Formula. This includes leadership changes, like the ousting of Bank of America's Chairman/CEO. But it takes more than changing one man, and more than one bank. It takes Disruption across the industry which will force it to change. Force it to open White Space in which it redefines the Success Formula to meet the needs of a shifted market – which almost pushed them over the edge – before those same shifts do crush the banks and the economy.

And that is now going to be up to the regulators. The poor Secretary of Treasury is already eyeball deep in complaints about his policies and practices. I'm sure he'd love to stand back and avoid more controversy. But, unless the regulatory apparatus now pushes those leading these banks to behave differently, to Disrupt and implement White Space to redefine their value for a changed marketplace, we can expect a protracted period of bickering and very weak returns for these banks. We can expect them to walk a line of ups and downs, but with returns that overall are neutral to declining. And that they will stand in the way of newer competitors who have a better approach to global banking from taking the lead.

So, if you didn't like government intervention to save the banks – you're really going to hate the government intervention intended to change how they operate. If you are glad the government intervened, then you'll find yourself arguing about why the regulators are just doing what they must do in order to get the banks, and the economy, operating the way it needs to in a shifted, information age.