by Adam Hartung | May 26, 2021 | Innovation, Investing, Software, Strategy, Trends

Free Trend Money!

Amazon is buying MGM film studios for something less than $9 B. Sounds like a lot of money. But since Amazon can make its own money, effectively this transaction is free. Now you must be wondering, how can Amazon make its own money? By creating “Trend Value.”

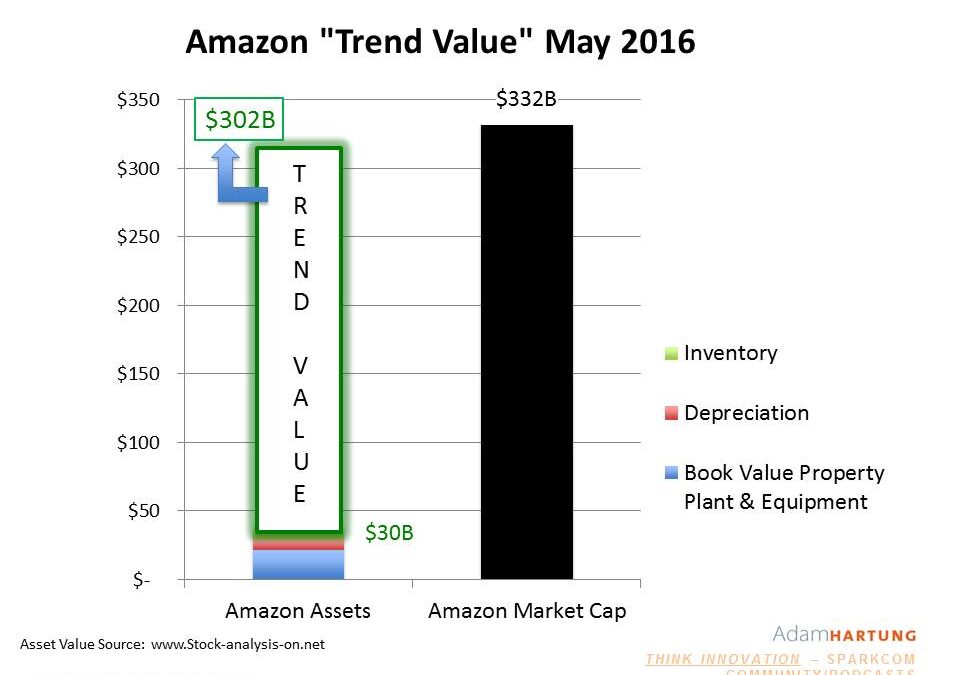

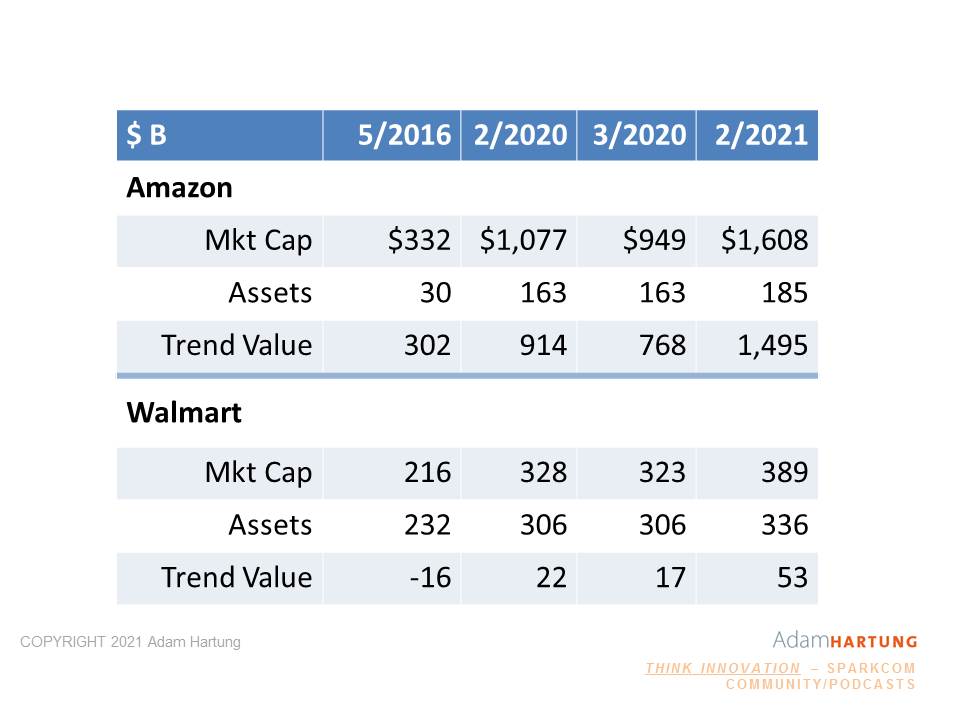

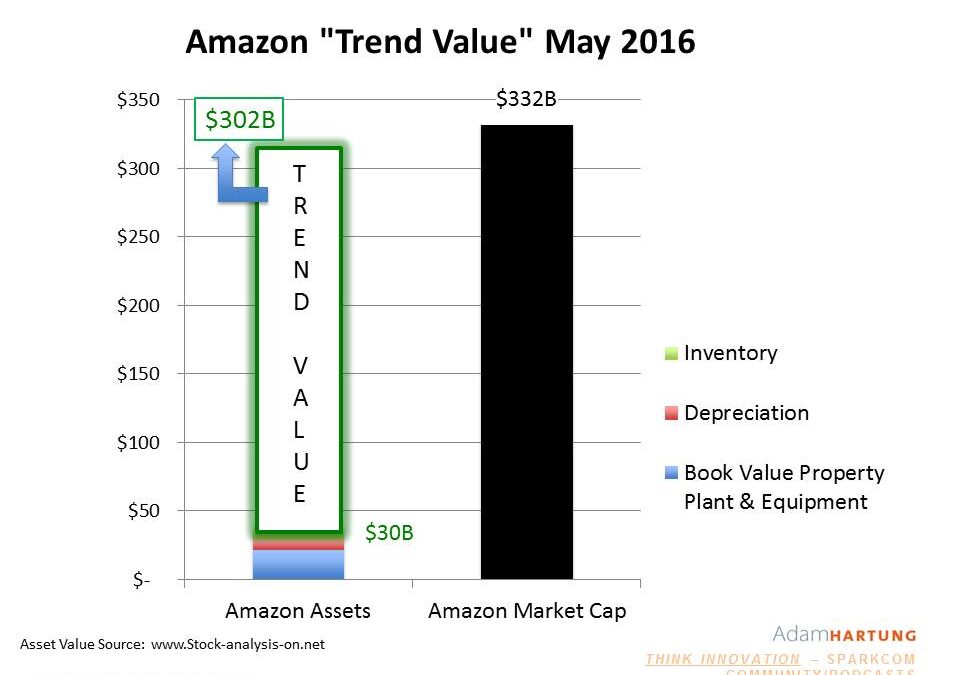

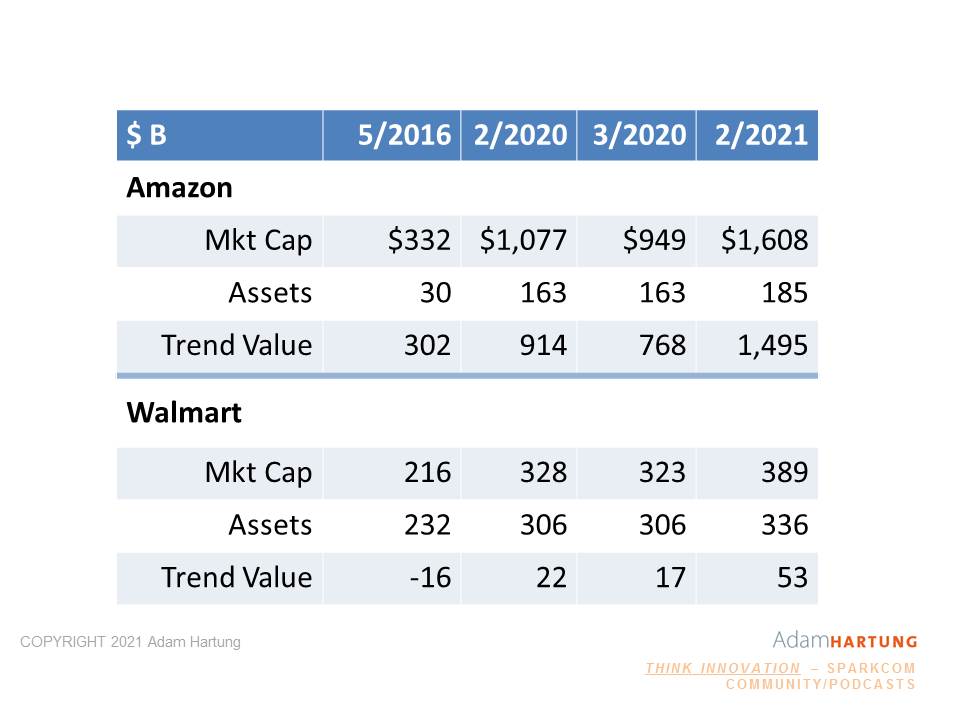

Back in 2016, before Amazon started making acquisitions like Whole Foods, its valuation (or market capitalization) was $332 B. But its assets were only worth $30 B. And remember, Amazon was not, and still isn’t, very profitable. Net income was only about $2 B at that time. That extra $300 B of valuation (10x the assets) wasn’t from earnings, but rather because Amazon was a global leader in e-commerce with about 40% market share in the USA. Because e-commerce and cloud computing were growing trends, investors gave Amazon an additional $300 B in value as a Trend Leader.

Because Amazon was riding the big trends to e-commerce it created $300 B of very real value. This very high share price allowed Amazon to keep investing in ways to grow, including making acquisitions.

Because Amazon was riding the big trends to e-commerce it created $300 B of very real value. This very high share price allowed Amazon to keep investing in ways to grow, including making acquisitions.

Compare with Walmart. In 2016 before, Walmart bought Jet, it had almost no e-commerce. Walmart had $232 B of assets (7 times the assets of Amazon,) but it’s valuation was only $216 B (2/3 Amazon’s.) Because Walmart’s assets (and business) were concentrated in the no-growth retail world of brick-and-mortar stores its value was less than its assets! Investors were basically saying that to create value Walmart would have to sell its assets – not grow its revenues. As a result, Walmart’s Trend Value was a NEGATIVE $16 B

Six years (and a pandemic) later, and the world of e-commerce has exploded. WalMart bought Jet, eschewing adding traditional stores and instead investing in e-commerce. As a result its assets grew very little, but its market valuation improved to $399 B, an 85% enhancement. And it’s Trend Value went up to $60 B. A good thing, but still only 1/5 the 2016 Trend Value of Amazon. A $9 B acquisition would be a very notable acquisition for Walmart using up over 50% of its cash. And taking out a 2.5% chunk of its market cap, and a whopping 15% of its enhanced Trend Value. Meanwhile, since 2016 Amazon has purchased an entire grocery chain (Whole Foods) and made enormous investments in distribution centers, trucks, and other supply chain assets. That has increased Amazon’s asset base 10-fold, to about $320B. But now Amazon’s publicly traded shares are worth $1.62 TRILLION. That’s right, with a “T.” By investing in Trends (e-commerce and cloud computing services [AWS]) Amazon’s Trend Value has risen to a whopping $1,300 Billion. Amazon’s Trend Value is 21.5x Walmart’s.

Meanwhile, since 2016 Amazon has purchased an entire grocery chain (Whole Foods) and made enormous investments in distribution centers, trucks, and other supply chain assets. That has increased Amazon’s asset base 10-fold, to about $320B. But now Amazon’s publicly traded shares are worth $1.62 TRILLION. That’s right, with a “T.” By investing in Trends (e-commerce and cloud computing services [AWS]) Amazon’s Trend Value has risen to a whopping $1,300 Billion. Amazon’s Trend Value is 21.5x Walmart’s.

By investing in Trends, Amazon created a cache of value

They used that value to make more acquisitions. Even though it made huge investments in assets – far beyond WalMart’s – its Trend Value grew even more. Now Amazon could purchase MGM for $9 B and use only 10% of its cash. But it won’t. It will use shares. But that $9 B is now only .55% of Amazon’s value – and only .7% of its Trend Value. Negligible on the balance sheet, but opening up tremendous revenue growth for Prime Video.

If you want to create money, invest in trends. Walmart was the renowned leader in retail, and computing for retail, until trends shifted the market. Now it is an also-ran compared to Amazon. And because Amazon is leading in the Trending markets of e-commerce and cloud computing it has created the money to buy MGM. Again, not with profits (which are still only $20 B) but with the Trend Value created by proper market selection and investing.

So are you creating money by investing in trends? You can literally create your own money, usable for all kinds of investments, when you invest in trends. Or are you grinding out the business, like Walmart with all those stores, but creating almost no value in the vast majority of what you do? The choice is really up to you.

Did you see the trends, and were you expecting the changes that would happen to your demand? It IS possible to use trends to make good forecasts, and prepare for big market shifts. If you don’t have time to do it, perhaps you should contact us, Spark Partners. We track hundreds of trends, and are experts at developing scenarios applied to your business to help you make better decisions.

TRENDS MATTER. If you align with trends your business can do GREAT! Are you aligned with trends? What are the threats and opportunities in your strategy and markets? Do you need an outsider to assess what you don’t know you don’t know? You’ll be surprised how valuable an inexpensive assessment can be for your future business. Click for Assessment info. Or, to keep up on trends, subscribe to our weekly podcasts and posts on trends and how they will affect the world of business at www.SparkPartners.com

Give us a call or send an email. Adam@sparkpartners.com 847-726-8465.

by Adam Hartung | Sep 1, 2020 | Finance, Investing, Strategy, Trends

On 8/31/20, the Dow Jones Industrial Average went through a change in composition. Out went Exxon, Pfizer and Raytheon. In came Salesforce.com, Amgen and Honeywell. This is the 8th time the Index components have changed this decade, the 13th time since 2000 and the 55th change since created in 1896. So changes are not uncommon. But, are they meaningful? Ask any academic and you’ll get a resounding “NO.” There is no stated criteria for selection, no metrics for inclusion, no breadth to the number of companies (which has changed significantly over time,) and not even a weighting for market capitalization! The DJIA has no relationship to “the market,” which could well be measured better by the S&P 500, or the Russell 3000. And it doesn’t even link to any specific industry! To academics, “the Dow” is just a random number that reflects nothing worth measuring!!

The DJIA is (currently) a group of 30 stocks selected by the editors of Dow Jones (publisher of the Wall Street Journal, owned by News Corp – which also owns Fox News – and controlled by Rupert Murdock). Despite its lack of respect by academics and money managers, because of its age – and the prestige of being selected by these editors – being on the DJIA has been considered somewhat revered. Think of it as an “editorial award of achievement” for size, profitability and perceived stability. For these reasons, over time many investors have believed the index represents a low–risk way to invest in corporations and grow their wealth.

So the daily value of the DJIA is pretty much meaningless. And being on the DJIA is also pretty much meaningless. But, investors have followed this index every trading day for 124 years. So, it is at least interesting. And that’s because it is a track on what these editors think are important very long-term economic trends.

The original Index composition looks NOTHING like 2020. American Cotton Oil Company, American Spirits Manufacturing Company, American Sugar Refining Company, American Tobacco Company, Chicago Gas Light and Coke, General Electric, Leclede Gas, National Lead, Pacific Mail Steamship Company, Tennessee Coal Iron and Railroad Company, United State Cordage Company and United States Leather Company. Familiar household names? This initial list represents the era in 1896 – an agrarian economy just on the cusp of coming into the industrial age. Not forward looking, but rather somewhat reflective of what were the biggest parts of the economy historically with a not forward.

Over 124 years lots of companies left the DJIA — were replaced – and many replacements left. Some came on, went off, and came back on again – such as AT&T, Exxon (formerly Standard Oil of New Jersey) and Chevron (formerly Standard Oil of California.) Even the vaunted GE was inducted in 1899, only to be removed in 1901 – then added back in 1907 where it stayed until CEO Jeff Immelt imploded the company and it was removed for good in 2018.

But, there has been a theme to the changes. Originally, the index was largely agricultural companies. As the economy changed, the Index rotated into commodity companies like gas, coal, copper and nickel – the materials leading to a new era of tools. This gave way to component manufacturers, dominated by the big steel companies, which created the industrial era. Which, of course, led to big manufacturing companies like 3M and IBM. And, along the way, there was recognition for growth in new parts of the economy, by adding consumer goods companies like P&G, Coca-Cola, McDonald’s, Kraft (since removed,) and Nike along with retailers like Sears (later removed,) Walmart, Home Depot and Walgreens. The massively important role of financial services to the economy was reflected by including Travelers, JPMorgan Chase, American Express, Visa and Goldman Sachs. And as health care advanced, the Index added pharmaceutical companies like Pfizer, Johnson & Johnson and Merck.

Obviously, the word “industrial” no longer has any meaning in the Dow Jones Industrial Index.

Reading across the long history of the DJIA one recognizes the editors’ willingness to try and reflect what was growing in the American economy. But in a laggard way. Not selecting companies too early, preferring instead to see that they make a big difference and remain important for many years. And a tendency to keep them on the index long after the bloom is off the rose – like retaining Kraft until 2008 and still holding onto P&G and Coke today.

The bias has always been to be careful about adding companies, lest they not be sustainable. And not judge too hastily the demise of once great companies. Disney wasn’t added until 1991, long after it was an established entertainment leader. Boeing was added in 1987, after pioneering aviation for 30 years. Microsoft added in 1999, well after it had won the PC war. Thus, the index is a “lagging index.” It reflects a big chunk of what was great, while slowly adding what has recently been great – and never moving too quickly to add companies that just might be tomorrow’s leaders.

Sears added in 1924, wasn’t removed until 1999 when its viability is questionable. Phillip Morris Tobacco (became Altria) was added in 1985, and hung around until 2008 — long after we knew cigarettes were deadly and leadership didn’t know how to do anything else. Even today we see that United Aircraft was added in 1939, which became United Technologies in 1976 and then via merger Raytheon in 2020 – before it is now removed, as all things aircraft are screeching to a pandemic halt. And Boeing is still on the Index despite the 737 fiasco and plunging sales. IBM was added in 1939, and through the 1970s it was a leader in office equipment creating the computer industry. But IBM after years of declining sales and profits isn’t really relevant any longer, yet it is still on the Index.

As for adding growing stars, GM stays on the Index until it goes bankrupt, but Tesla is yet to make consideration (largely due to lack of profit history.) Likewise, Walmart remains even though the “big gun” in retail is obviously Amazon.com (another lacking the size and longevity of profits the editors like.) McDonald’s stays on the list, despite no growth for years and even as the Board investigates its HR department for hiding abhorrent leadership behavior – while Starbucks is eschewed. And Cisco is there, while we all use Zoom for pandemic-driven virtual meetings.

So what can we take away from today’s changes? First, the Index has changed dramatically over 20 years to reflect electronic technology. IBM, Microsoft and Apple are now joined by Salesforce. Pharma company Pfizer is being replaced by bio-pharma company Amgen in a nod to the future, although almost 40 years after Genentech went public. Exxon disappears as oil prices fall to sub-zero, demand declines globally and electric cars are on the cusp of taking market leadership. And conglomerate Honeywell is added just to show the editors still think conglomerates matter – even if GE has nearly disintegrated.

Is any of this meaningful? I don’t really think so. As an award for past performance, it’s a nice token to make the list. As business leaders, however, we need to be a LOT more concerned about developing businesses for the future, based on trends, than is indicated by the components of the DJIA. Driving revenue growth and higher margins comes from doing the next big thing, not the last big thing. And, as investors, if you want to make outsized returns you have to know that a basket of largely laggards (Apple, Microsoft and Salesforce excepted) is not the way to build your retirement nest. Instead, you have to invest in companies that are creating the future, making the trends a reality for businesses and consumers. Think FAANG.

Nonetheless, after 124 years it is still sort of interesting. I guess most of us do still care what the editors of big news companies think.

TRENDS MATTER. If you align with trends your business can do GREAT! Are you aligned with trends? What are the threats and opportunities in your strategy and markets? Do you need an outsider to assess what you don’t know you don’t know? You’ll be surprised how valuable an inexpensive assessment can be for your future business (https://adamhartung.com/assessments/)

Give us a call or send an email. Adam@sparkpartners.com

by Adam Hartung | Jun 5, 2018 | Investing, Retail, Strategy, Trends, Web/Tech

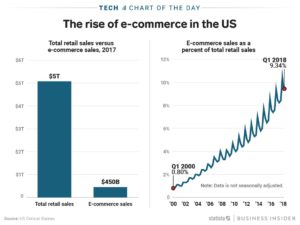

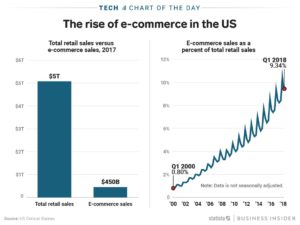

The US e-commerce market is just under 10% the size of entire retail market. On the face of it this would indicate that the game is far from over for big traditional retail. After all, how could such a small segment kill profits for such a huge industry based on enormous traditional players?

Yet, Sears – once a Dow Jones component and the world’s most powerful retailer – has announced it will close 100 more stores. The Kmart/Sears chain is now only 894 stores – down from thousands at its peak and 1,275 just last year. Revenue dropped 30% versus a year ago, and quarterly losses of $424M were almost 15% of revenues.

But, that ignores marginal economics. It often doesn’t take a monster change in one factor to have a huge impact on the business model. Let’s say Sales are $100. Less Cost of Goods sold of $75. That leaves a Gross Margin of $25. Selling, General and Administrative costs are 20%, so Operating Income is only $5. The Net Margin before Interest and Taxes is 5%. (BTW, these are the actual percentages of Walmart from 1/31/18.)

Now, in comes a new competitor – like Amazon.com. They have no stores, no store clerks, and minimal inventory due to “e-storefront” selling. So, they are able to lower prices by 5%. That seems pretty small – just a 5% discount compared to typical sales of 20%, 30% even 50% (BOGO) in retail stores. Amazon’s 5% price reduction seems like no big deal to established firms.

But, Walmart has to lower prices by 5% in response, which lowers revenues to $95. But the stores, clerks, inventory, distribution centers and trucks all largely remain. With Cost of Goods Sold still $75, Gross Margin falls to $20. Fixed headquarters costs, general and administrative costs don’t change, so they remain at $20. This leaves Operating Income of …$0.

(For more detailed analysis see “Bigger is Not Always Better – Why Amazon is Worth More than Walmart” from July, 2015.)

How can Walmart survive with no profits? It can’t. To get some margin back, Walmart has to start shutting stores, selling assets, cutting pay, using automation to cut headcount, beating on vendors to offer them better prices. This earns praise as “a low cost operation.” When in fact, this makes Walmart a less competitive company, because it’s footprint and service levels decline, which encourages people to do more shopping on-line. A vicious circle begins of trying to recapture lost profitability, while sales are declining rather than growing.

Walmart was (and is) huge. Even Sears was much bigger than Amazon.com at the beginning. But to compete with Amazon.com both had to lower prices on ALL of their products in ALL of their stores. So the hit to Walmart’s, and Sears’, revenue is a huge number. Though Amazon.com was a much, much smaller company, its impact explodes on the larger competitor P&L’s.

This disruption is felt across the entire industry: ALL traditional retailers are forced to match Amazon and other e-commerce companies, even though there is no way they can cut costs enough to compete. Thus, Toys-R-Us, Radio Shack, Claire’s and Bon-Ton have declared bankruptcy in 2018, and the once great, dominant Sears is on the precipice of extinction.

All of which is good news for Amazon.com investors. Amazon.com has 40% market share of the entire e-commerce business. The fact that e-commerce is only 10% of all retail is great news for Amazon investors. That means there is still an enormously large market of traditional retail available to convert to on-line sales.

The shift to e-commerce will not be stopping, or even slowing. Since January, 2010 the future has been easily predictable for traditional retail’s decline. The next few years will see a transition of an additional $2.5 trillion on-line, which is 5X the size of the existing e-commerce market!

As stores close new competitors will emerge in the e-commerce market. But undoubtedly the big winner will be the company with 40% market share today – Amazon.com. So what will Amazon’s stock be worth when sales are 5x larger (or more) and Amazon can increase profits by making leveraging its infrastructure and slow future investments?

Twenty years ago, Amazon was a retail ant. And retail elephants ignored it. But that was foolish, because Amazon had a different business model with an entirely different cost of operations. And now the elephants are falling fast, due to their inability to adapt to new market conditions and maintain their growth.

_________________________________________________________________________

Author’s Note: In June, 2007 I was asked to predict WalMart’s future. Here are the predictions I made 11 years ago:

- “In 5 years (2012) Walmart would not have succeeded internationally” [True: Mexico, China, Germany all failed]

- “In 5 years (2012) Walmart would no new businesses, and its revenue will be stalled” [True]

- In 5 years (2012) Walmart would be spending more on stock repurchases then investing in its own stores or distribution” [True – and the Walton’s were moving money out of Walmart to other investments]

- “In 10 years (2017) Walmart would take a dramatic act, and make an acquisition” [True: Jet.com]

- “In 10 years (2017 Walmart’s value would not keep up with the stock market” [from 6/2007 to 6/2017 WMT went from $48 to $75 up 56.25%, DIA went from $134 to $180 up 34.3%, AMZN went from $70 to $1,000 up 1,330% or 13.3x]

- “In 30 years (2037) Walmart will only be known as “a once great company, like General Motors”

by Adam Hartung | Apr 25, 2018 | Entertainment, Film, Innovation, Investing, Retail

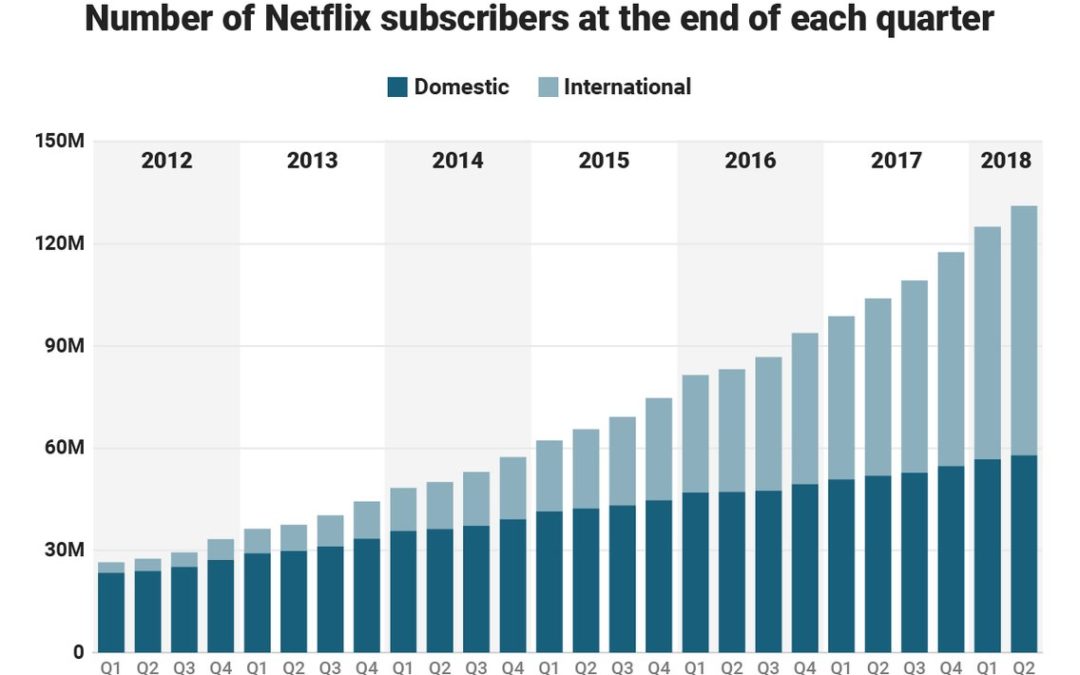

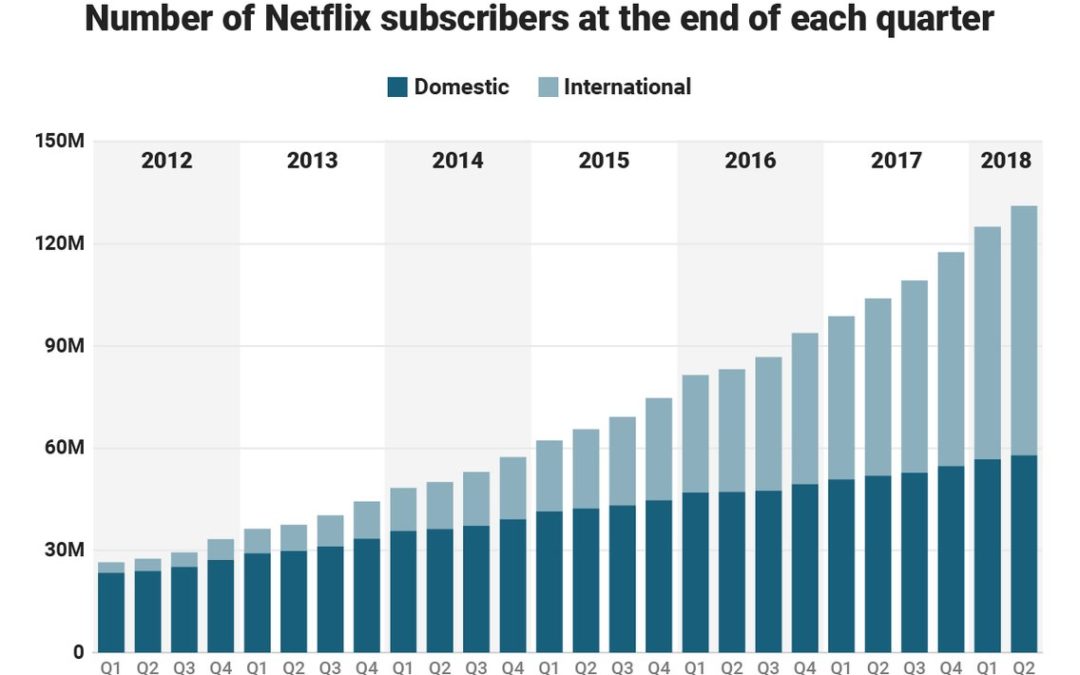

Netflix announced new subscriber numbers last week – and it exceeded expectations. Netflix now has over 130 million worldwide subscribers. This is up 480% in just the last 6 years – from under 30 million. Yes, the USA has grown substantially, more than doubling during this timeframe. But international growth has been spectacular, growing from almost nothing to 57% of total revenues. International growth the last year was 70%, and the contribution margin on international revenues has transitioned from negative in 2016 to over 15% – double the 4th quarter of 2017.

Accomplishing this is a remarkable story. Most companies grow by doing more of the same. Think of Walmart that kept adding stores. Then adding spin-off store brand Sam’s Club. Then adding groceries to the stores. Walmart never changed its strategy, leaders just did “more” with the old strategy. That’s how most people grow, by figuring out ways to make the Value Delivery System (in their case retail stores, warehouses and trucks) do more, better, faster, cheaper. Walmart never changed its strategy.

But Netflix is a very different story. The company started out distributing VHS tapes, and later DVDs, to homes via USPS, UPS and Fedex. It was competing with Blockbuster, Hollywood Video, Family Video and other traditional video stores. It won that battle, driving all of them to bankruptcy. But then to grow more Netflix invested far outside its “core” distribution skills and pioneered video streaming, competing with companies like DirecTV and Comcast. Eventually Netflix leaders raised prices on physical video distribution, cannibalizing that business, to raise money for investing in streaming technology. Streaming technology, however, was not enough to keep growing subscribers. Netflix leadership turned to creating its own content, competing with moviemakers, television and documentary producers, and broadcast television. The company now spends over $6B annually on content.

Think about those decisions. Netflix “pivoted” its strategy 3 times in one decade. Its “core” skill for growth changed from physical product distribution to network technology to content creation. From a “skills” perspective none of these have anything in common.

Could you do that? Would you do that?

How did Netflix do that? By focusing on its Value Proposition. By realizing that it’s Value Proposition was “delivering entertainment” Netflix realized it had to change its skill set 3 times to compete with market shifts. Had Netflix not done so, its physical distribution would have declined due to the emergence of Amazon.com, and eventually disappeared along with tapes and DVDs. Netflix would have followed Blockbuster into history. And as bandwidth expanded, and global networks grew, and dozens of providers emerged streaming purchased content profits would have become a bloodbath. Broadcasters who had vast libraries of content would sell to the cheapest streaming company, stripping Netflix of its growth. To continue growing, Netflix had to look at where markets were headed and redirect the company’s investments into its own content.

This is not how most companies do strategy. Most try to figure out one thing they are good at, then optimize it. They examine their Value Delivery System, focus all their attention on it, and entirely lose track of their Value Proposition. They keep optimizing the old Value Delivery System long after the market has shifted. For example, Walmart was the “low cost retailer.” But e-commerce allows competitors like Amazon.com to compete without stores, without advertising and frequently without inventory (using digital storefronts to other people’s inventory.) Walmart leaders were so focused on optimizing the Value Delivery System, and denying the potential impact of e-commerce, that they did not see how a different Value Delivery System could better fulfill the initial Walmart Value Proposition of “low cost.” The Walmart strategy never took a pivot – and now they are far, far behind the leader, and rapidly becoming obsolete.

Do you know your Value Proposition? Is it clear – written on the wall somewhere? Or long ago did you stop thinking about your Value Proposition in order to focus your intention on optimizing your Value Delivery System?

That fundamental strategy flaw is killing companies right and left – Radio Shack, Toys-R-Us and dozens of other retailers. Who needs maps when you have smartphone navigation? Smartphones put an end to Rand McNally. Who needs an expensive watch when your phone has time and so much more? Apple Watch sales in 2017 exceeded the entire Swiss watch industry. Who needs CDs when you can stream music? Sony sales and profits were gutted when iPods and iPhones changed the personal entertainment industry. (Anyone remember “boom boxes” and “Walkman”?)

I’ve been a huge fan of Netflix. In 2010, I predicted it was the next Apple or Google. When the company shifted strategy from delivering physical entertainment to streaming in 2011, and the stock tanked, I made the case for buying the stock. In 2015 when the company let investors know it was dumping billions into programming I again said it was strategically right, and recommended Netflix as a good investment. And I redoubled my praise for leadership when the “double pivot” to programming was picking up steam in 2016. You don’t have to be mystical to recognize a winner like Netflix, you just have to realize the company is using its strategy to deliver on its Value Proposition, and is willing to change its Value Delivery System because “core strength” isn’t important when its time to change in order to meet new market needs.

by Paul F | Apr 12, 2018 | E-Commerce, Ecommerce, Investing, Retail

President Trump has been bashing Amazon of late. And Amazon is down about 12.5% since peaking on March 12, 2018. Simultaneously the DJIA fell 10% from 1/26/18 thru 4/3/18, so it is hard to discern if Amazon’s pullback has more to do with market conditions and trade war fears or Presidential bashing. Amazon’s performance has been only slightly worse than the Dow. Anyway, one would think that if the President is right and Amazon plays unfairly, the future would bode well for Walmart.

That is very unlikely. Since peaking on January 29, just after the Dow, Walmart crashed 32% by April 3. Over the last month the stock has stabilized, but unfortunately the signs are not good for Walmart investors.

Walmart leadership has never shown a keen understanding of e-commerce, nor a commitment to making Walmart a leading market competitor. You might counter that Walmart’s acquisition of Jet.com showed a strong commitment. But we now know that amidst the minimalistic hype, Walmart actually cheated when providing its e-commerce results. And when Walmart hired a former Tesco executive to lead Jet.com’s grocery sales effort, the news was not splashed front page. Rather it was hidden in an internal email discovered by Reuters and given almost no coverage. Like Walmart was afraid to let people know it was incompetent and hiring an outsider.

Walmart leadership has never shown a keen understanding of e-commerce, nor a commitment to making Walmart a leading market competitor. You might counter that Walmart’s acquisition of Jet.com showed a strong commitment. But we now know that amidst the minimalistic hype, Walmart actually cheated when providing its e-commerce results. And when Walmart hired a former Tesco executive to lead Jet.com’s grocery sales effort, the news was not splashed front page. Rather it was hidden in an internal email discovered by Reuters and given almost no coverage. Like Walmart was afraid to let people know it was incompetent and hiring an outsider.

Investors, and customers, need to admit that it is a LOT easier for Amazon to learn about traditional store operations by purchasing Whole Foods than it is for Walmart to learn how to succeed in e-commerce. Traditional grocery “excellence” is easy to come by, after all there are thousands of experienced grocery store executives. So Amazon can buy Whole Foods and gain what knowledge it needs overnight, while adapting Whole Foods to the tremendous e-commerce insight embedded in Amazon. But Walmart is struggling to add compete with Amazon in e-commerce, where knowledge is a lot, lot tougher to come by.

Telltale’s are strips of cloth used by sailors to provide early tips about wind direction and speed. Good sailors “read” the telltale strips to plot their sail use for maximum performance. We can read the “telltales” in business as well. The “telltales” at Walmart have long been bad signals for investors. After 3 years of recovery from a 2014 collision created by an overworked Walmart driver, comedian Tracy Morgan recently returned to television with a new show. The overworked driver was a worrisome telltale of how Walmart pressured its employees to attempt competing against much lower cost e-commerce. By February, 2016 there were 10 very obvious telltales of Walmart’s inability to cope with Amazon and the market shift to e-commerce.

Understanding e-commerce is worth a whole lot more than being good at running a tight retail operation. As I pointed out in May, 2016, knowing that trend is what makes Amazon worth so much more than the much bigger, and asset rich, Walmart. And the Walton family knows this, that’s why it became clear by October, 2017 that they were cashing out of the traditional Walmart business. As I’ve said before, if the Walton’s aren’t putting their money in Walmart (or shopping in the stores) why should you?

Because Amazon was riding the big trends to e-commerce it created $300 B of very real value. This very high share price allowed Amazon to keep investing in ways to grow, including making acquisitions.

Because Amazon was riding the big trends to e-commerce it created $300 B of very real value. This very high share price allowed Amazon to keep investing in ways to grow, including making acquisitions. Meanwhile, since 2016 Amazon has purchased an entire grocery chain (Whole Foods) and made enormous investments in distribution centers, trucks, and other supply chain assets. That has increased Amazon’s asset base 10-fold, to about $320B. But now Amazon’s publicly traded shares are worth $1.62 TRILLION. That’s right, with a “T.” By investing in Trends (e-commerce and cloud computing services [AWS]) Amazon’s Trend Value has risen to a whopping $1,300 Billion. Amazon’s Trend Value is 21.5x Walmart’s.

Meanwhile, since 2016 Amazon has purchased an entire grocery chain (Whole Foods) and made enormous investments in distribution centers, trucks, and other supply chain assets. That has increased Amazon’s asset base 10-fold, to about $320B. But now Amazon’s publicly traded shares are worth $1.62 TRILLION. That’s right, with a “T.” By investing in Trends (e-commerce and cloud computing services [AWS]) Amazon’s Trend Value has risen to a whopping $1,300 Billion. Amazon’s Trend Value is 21.5x Walmart’s.

Walmart leadership has never shown a keen understanding of e-commerce, nor a commitment to making Walmart a leading market competitor. You might counter that Walmart’s acquisition of Jet.com showed a strong commitment. But we now know that amidst the minimalistic hype,

Walmart leadership has never shown a keen understanding of e-commerce, nor a commitment to making Walmart a leading market competitor. You might counter that Walmart’s acquisition of Jet.com showed a strong commitment. But we now know that amidst the minimalistic hype,