by Adam Hartung | Nov 6, 2013 | Defend & Extend, Innovation, Leadership, Web/Tech

Can you believe it has been only 12 years since Apple introduced the iPod? Since then Apple’s value has risen from about $11 (January, 2001) to over $500 (today) – an astounding 45X increase.

With all that success it is easy to forget that it was not a “gimme” that the iPod would succeed. At that time Sony dominated the personal music world with its Walkman hardware products and massive distribution through consumer electronics chains such as Best Buy, and broad-line retailers like Wal-Mart. Additionally, Sony had its own CD label, from its acquisition of Columbia Records (renamed CBS Records,) producing music. Sony’s leadership looked impenetrable.

But, despite all the data pointing to Sony’s inevitable long-term domination, Apple launched the iPod. Derided as lacking CD quality, due to MP3’s compression algorithms, industry leaders felt that nobody wanted MP3 products. Sony said it tried MP3, but customers didn’t want it.

All the iPod had going for it was a trend. Millions of people had downloaded MP3 songs from Napster. Napster was illegal, and users knew it. Some heavy users were even prosecuted. But, worse, the site was riddled with viruses creating havoc with all users as they downloaded hundreds of millions of songs.

Eventually Napster was closed by the government for widespread copyright infreingement. Sony, et.al., felt the threat of low-priced MP3 music was gone, as people would keep buying $20 CDs. But Apple’s new iPod provided mobility in a way that was previously unattainable. Combined with legal downloads, including the emerging Apple Store, meant people could buy music at lower prices, buy only what they wanted and literally listen to it anywhere, remarkably conveniently.

The forecasted “numbers” did not predict Apple’s iPod success. If anything, good analysis led experts to expect the iPod to be a limited success, or possibly failure. (Interestingly, all predictions by experts such as IDC and Gartner for iPhone and iPad sales dramatically underestimated their success, as well – more later.) It was leadership at Apple (led by the returned Steve Jobs) that recognized the trend toward mobility was more important than historical sales analysis, and the new product would not only sell well but change the game on historical leaders.

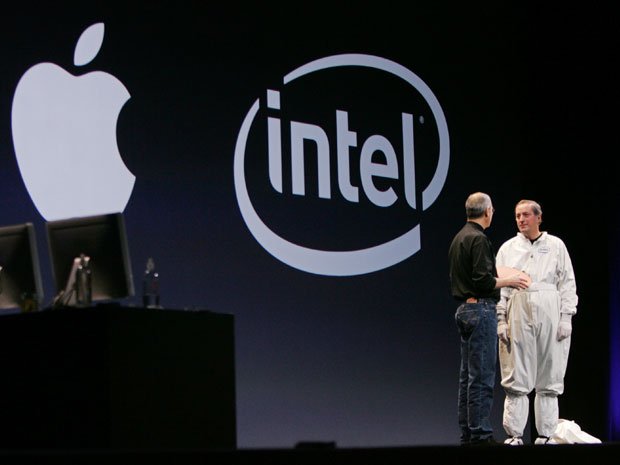

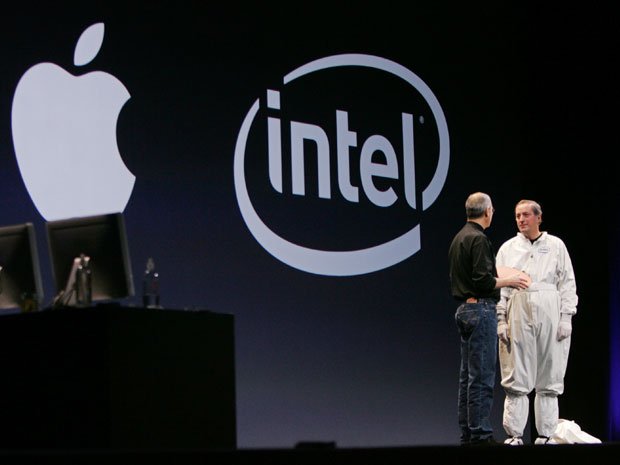

Which takes us to the mistake Intel made by focusing on “the numbers” when given the opportunity to build chips for the iPhone. Intel was a very successful company, making key components for all Microsoft PCs (the famous WinTel [for Windows+Intel] platform) as well as the Macintosh. So when Apple asked Intel to make new processors for its mobile iPhone, Intel’s leaders looked at the history of what it cost to make chips, and the most likely future volumes. When told Apple’s price target, Intel’s leaders decided they would pass. “The numbers” said it didn’t make sense.

Uh oh. The cost and volume estimates were wrong. Intel made its assessments expecting PCs to remain strong indefinitely, and its costs and prices to remain consistent based on historical trends. Intel used hard, engineering and MBA-style analysis to build forecasts based on models of the past. Intel’s leaders did not anticipate that the new mobile trend, which had decimated Sony’s profits in music as the iPod took off, would have the same impact on future sales of new phones (and eventually tablets) running very thin apps.

Harvard innovation guru Clayton Christensen tells audiences that we have complete knowledge about the past. And absolutely no knowledge about the future. Those who love numbers and analysis can wallow in reams and reams of historical information. Today we love the “Big Data” movement which uses the world’s most powerful computers to rip through unbelievable quantities of historical data to look for links in an effort to more accurately predict the future. We take comfort in thinking the future will look like the past, and if we just study the past hard enough we can have a very predictible future.

But that isn’t the way the business world works. Business markets are incredibly dynamic, subject to multiple variables all changing simultaneously. Chaos Theory lecturers love telling us how a butterfly flapping its wings in China can cause severe thunderstorms in America’s midwest. In business, small trends can suddenly blossom, becoming major trends; trends which are easily missed, or overlooked, possibly as “rounding errors” by planners fixated on past markets and historical trends.

Markets shift – and do so much, much faster than we anticipate. Old winners can drop remarkably fast, while new competitors that adopt the trends become “game changers” that capture the market growth.

In 2000 Apple was the “Mac” company. Pretty much a one-product company in a niche market. And Apple could easily have kept trying to defend & extend that niche, with ever more problems as Wintel products improved.

But by understanding the emerging mobility trend leadership changed Apple’s investment portfolio to capture the new trend. First was the iPod, a product wholly outside the “core strengths” of Apple and requiring new engineering, new distribution and new branding. And a product few people wanted, and industry leaders rejected.

Then Apple’s leaders showed this talent again, by launching the iPhone in a market where it had no history, and was dominated by Motorola and RIMM/BlackBerry. Where, again, analysts and industry leaders felt the product was unlikely to succeed because it lacked a keyboard interface, was priced too high and had no “enterprise” resources. The incumbents focused on their past success to predict the future, rather than understanding trends and how they can change a market.

Too bad for Intel. And Blackberry, which this week failed in its effort to sell itself, and once again changed CEOs as the stock hit new lows.

Then Apple did it again. Years after Microsoft attempted to launch a tablet, and gave up, Apple built on the mobility trend to launch the iPad. Analysts again said the product would have limited acceptance. Looking at history, market leaders claimed the iPad was a product lacking usability due to insufficient office productivity software and enterprise integration. The numbers just did not support the notion of investing in a tablet.

Anyone can analyze numbers. And today, we have more numbers than ever. But, numbers analysis without insight can be devastating. Understanding the past, in grave detail, and with insight as to what used to work, can lead to incredibly bad decisions. Because what really matters is vision. Vision to understand how trends – even small trends – can make an enormous difference leading to major market shifts — often before there is much, if any, data.

by Adam Hartung | Apr 20, 2012 | Current Affairs, In the Swamp, Lifecycle, Lock-in, Television, Web/Tech

Who can forget what a great company Sony was, and the enormous impact it had on our lives? With its heritage, it is hard to believe that Sony hasn't made a profit in 4 consecutive years, just recently announced it will double its expected loss for this year to $6.4 billion, has only 15% of its capital left as equity (debt/equity ration of 5.67x) and is only worth 1/4 of its value 10 years ago!

After World War II Sony was the company that took the transistor technology invented by Texas Instruments (TI) and made the popular, soon to become ubiquitous, transistor radio. Under co-founder Akio Morita Sony kept looking for advances in technology, and its leadership spent countless hours innovatively thinking about how to apply these advances to improve lives. With a passion for creating new markets, Sony was an early creator, and dominator, of what we now call "consumer electronics:"

- Sony improved solid state transistor radios until they surpassed the quality of tubes, making good quality sound available very reliably, and inexpensively

- Sony developed the solid state television, replacing tubes to make TVs more reliable, better working and use less energy

- Sony developed the Triniton television tube, which dramatically improved the quality of color (yes Virginia, once TV was all in black & white) and enticed an entire generation to switch. Sony also expanded the size of Trinitron to make larger sets that better fit larger homes.

- Sony was an early developer of videotape technology, pioneering the market with Betamax before losing a battle with JVC to be the standard (yes Virginia, we once watched movies on tape)

- Sony pioneered the development of camcorders, for the first time turning parents – and everyone – into home movie creators

- Sony pioneered the development of independent mobile entertainment by creating the Walkman, which allowed – for the first time – people to take their own recorded music with them, via cassette tapes

- Sony pioneered the development of compact discs for music, and developed the Walkman CD for portable use

- Sony gave us the Playstation, which went far beyond Nintendo in creating the products that excited users and made "home gaming" a market.

Very few companies could ever boast a string of such successful products. Stories about Sony management meetings revealed a company where executives spent 85% of their time on technology, products and new applications/markets, 10% on human resource issues and 5% on finance. To Mr. Morita financial results were just that – results – of doing a good job developing new products and markets. If Sony did the first part right, the results would be good. And they were.

By the middle 1980s, America was panicked over the absolute domination of companies like Sony in product manufacturing. Not only consumer electronics, but automobiles, motorcycles, kitchen electronics and a growing number of markets. Politicians referred to Japanese competitors, like the wildly successful Sony, as "Japan Inc." – and discussed how the powerful Japanese Ministry of Trade and Industry (MITI) effectively shuttled resources around to "beat" American manufacturers. Even as rising petroleum costs seemed to cripple U.S. companies, Japanese manufacturers were able to turn innovations (often American) into very successful low-cost products growing sales and profits.

So what went wrong for Sony?

Firstly was the national obsession with industrial economics. W. Edward Deming in 1950s Japan institutionalized manufacturing quality and optimization. Using a combination of process improvements and arithmetic, Deming convinced Japanese leaders to focus, focus, focus on making things better, faster and cheaper. Taking advantage of Japanese post war dependence on foreign capital, and foreign markets, this U.S. citizen directed Japanese industry into an obsession with industrialization as practiced in the 1940s — and was credited for creating the rapid massive military equipment build-up that allowed the U.S. to defeat Japan.

Unfortunately, this narrow obsession left Japanese business leaders, buy and large, with little skill set for developing and implementing R&D, or innovation, in any other area. As time passed, Sony fell victim to developing products for manufacturing, rather than pioneering new markets.

The Vaio, as good as it was, had little technology for which Sony could take credit. Sony ended up in a cost/price/manufacturing war with Dell, HP, Lenovo and others to make cheap PCs – rather than exciting products. Sony's evolved a distinctly Industrial strategy, focused on manufacturing and volume, rather than trying to develop uniquely new products that were head-and-shoulders better than competitors.

In mobile phones Sony hooked up with, and eventually acquired, Ericsson. Again, no new technology or effort to make a wildly superior mobile device (like Apple did.) Instead Sony sought to build volume in order to manufacture more phones and compete on price/features/functions against Nokia, Motorola and Samsung. Lacking any product or technology advantage, Samsung clobbered Sony's Industrial strategy with lower cost via non-Japanese manufacturing.

When Sony updated its competition in home movies by introducing Blue Ray, the strategy was again an Industrial one – about how to sell Blue Ray recorders and players. Sony didn't sell the Blue Ray software technology in hopes people would use it. Instead it kept it proprietary so only Sony could make and sell Blue Ray products (hardware). Just as it did in MP3, creating a proprietary version usable only on Sony devices. In an information economy, this approach didn't fly with consumers, and Blue Ray was a money loser largely irrelevant to the market – as is the now-gone Sony MP3 product line.

We see this across practically all the Sony businesses. In televisions, for example, Sony has lost the technological advantage it had with Trinitron cathode ray tubes. In flat screens Sony has applied a predictable, but money losing Industrial strategy trying to compete on volume and cost. Up against competitors sourcing from lower cost labor, and capital, countries Sony has now lost over $10B over the last 8 years in televisions. Yet, Sony won't give up and intends to stay with its Industrial strategy even as it loses more money.

Why did Sony's management go along with this? As mentioned, Akio Morita was an innovator and new market creator. But, Mr. Morita lived through WWII, and developed his business approach before Deming. Under Mr. Morita, Sony used the industrial knowledge Deming and his American peers offered to make Sony's products highly competitive against older technologies. The products led, with industrial-era tactics used to lower cost.

But after Mr. Morita other leaders were trained, like American-minted MBAs, to implement Industrial strategies. Their minds put products, and new markets, second. First was a commitment to volume and production – regardless of the products or the technology. The fundamental belief was that if you had enough volume, and you cut costs low enough, you would eventually succeed.

By 2005 Sony reached the pinnacle of this strategic approach by installing a non-Japanese to run the company. Sir Howard Stringer made his fame running Sony's American business, where he exemplified Industrial strategy by cutting 9,000 of 30,000 U.S. jobs (almost a full third.) To Mr. Stringer, strategy was not about innovation, technology, products or new markets.

Mr. Stringer's Industrial strategy was to be obsessive about costs. Where Mr. Morita's meetings were 85% about innovation and market application, Mr. Stringer brought a "modern" MBA approach to the Sony business, where numbers – especially financial projections – came first. The leadership, and management, at Sony became a model of MBA training post-1960. Focus on a narrow product set to increase volume, eschew costly development of new technologies in favor of seeking high-volume manufacturing of someone else's technology, reduce product introductions in order to extend product life, tooling amortization and run lengths, and constantly look for new ways to cut costs. Be zealous about cost cutting, and reward it in meetings and with bonuses.

Thus, during his brief tenure running Sony Mr. Stringer will not be known for new products. Rather, he will be remembered for initiating 2 waves of layoffs in what was historically a lifetime employment company (and country.) And now, in a nod to Chairman Stringer the new CEO at Sony has indicated he will react to ongoing losses by – you guessed it – another round of layoffs. This time it is estimated to be another 10,000 workers, or 6% of the employment. The new CEO, Mr. Hirai, trained at the hand of Mr. Stringer, demonstrates as he announces ever greater losses that Sony hopes to – somehow – save its way to prosperity with an Industrial strategy.

Japanese equity laws are very different that the USA. Companies often have much higher debt levels. And companies can even operate with negative equity values – which would be technical bankruptcy almost everywhere else. So it is not likely Sony will fill bankruptcy any time soon.

But should you invest in Sony? After 4 years of losses, and entrenched Industrial strategy with MBA-style leadership focused on "numbers" rather than markets, there is no reason to think the trajectory of sales or profits will change any time soon.

As an employee, facing ongoing layoffs why would you wish to work at Sony? A "me too" product strategy with little technical innovation that puts all attention on cost reduction would not be a fun place. And offers little promotional growth.

And for suppliers, it is assured that each and every meeting will be about how to lower price – over, and over, and over.

Every company today can learn from the Sony experience. Sony was once a company to watch. It was an innovative leader, that pioneered new markets. Not unlike Apple today. But with its Industrial strategy and MBA numbers- focused leadership it is now time to say, sayonara. Sell Sony, there are more interesting companies to watch and more profitable places to invest.