by Adam Hartung | May 15, 2016 | In the Swamp, Investing, real estate, Retail

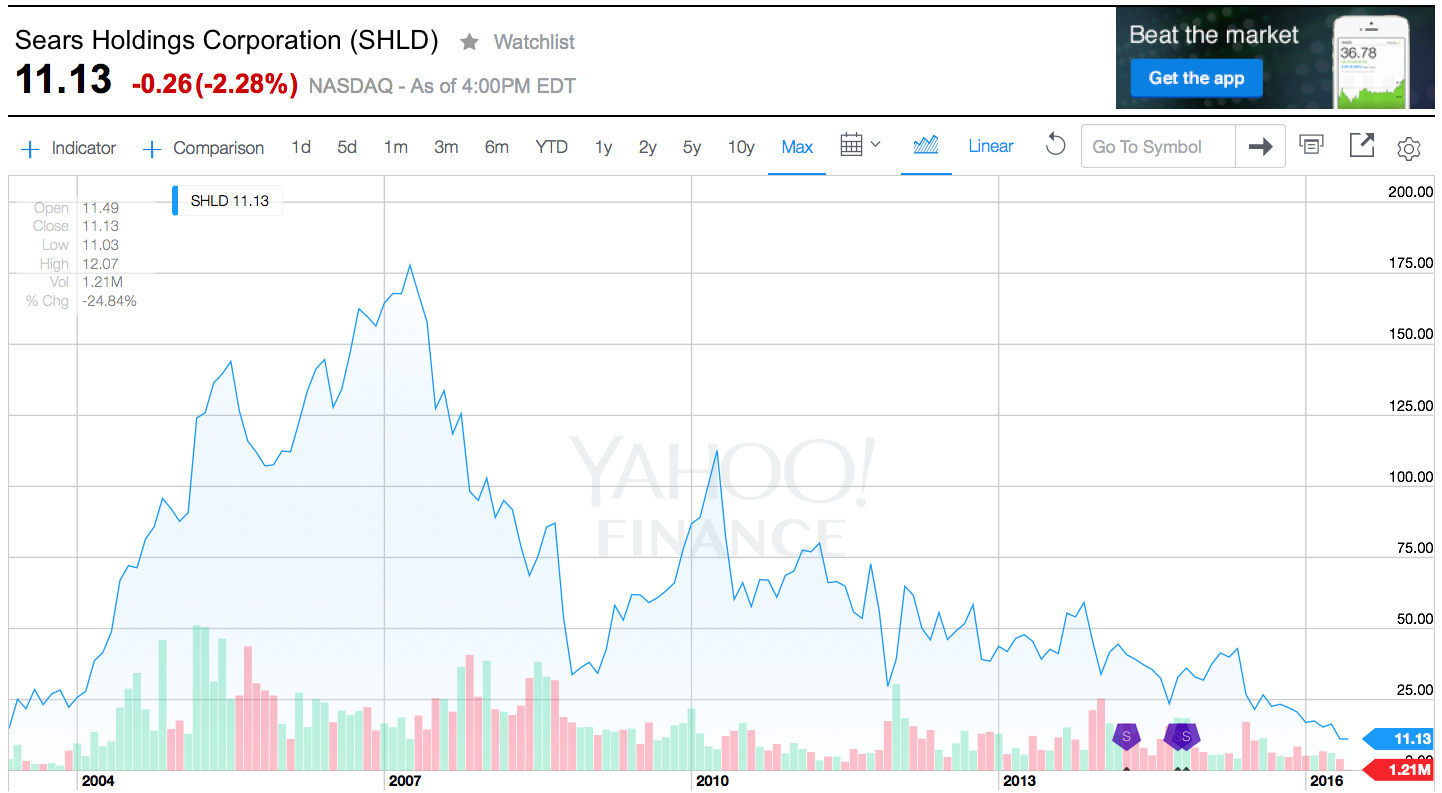

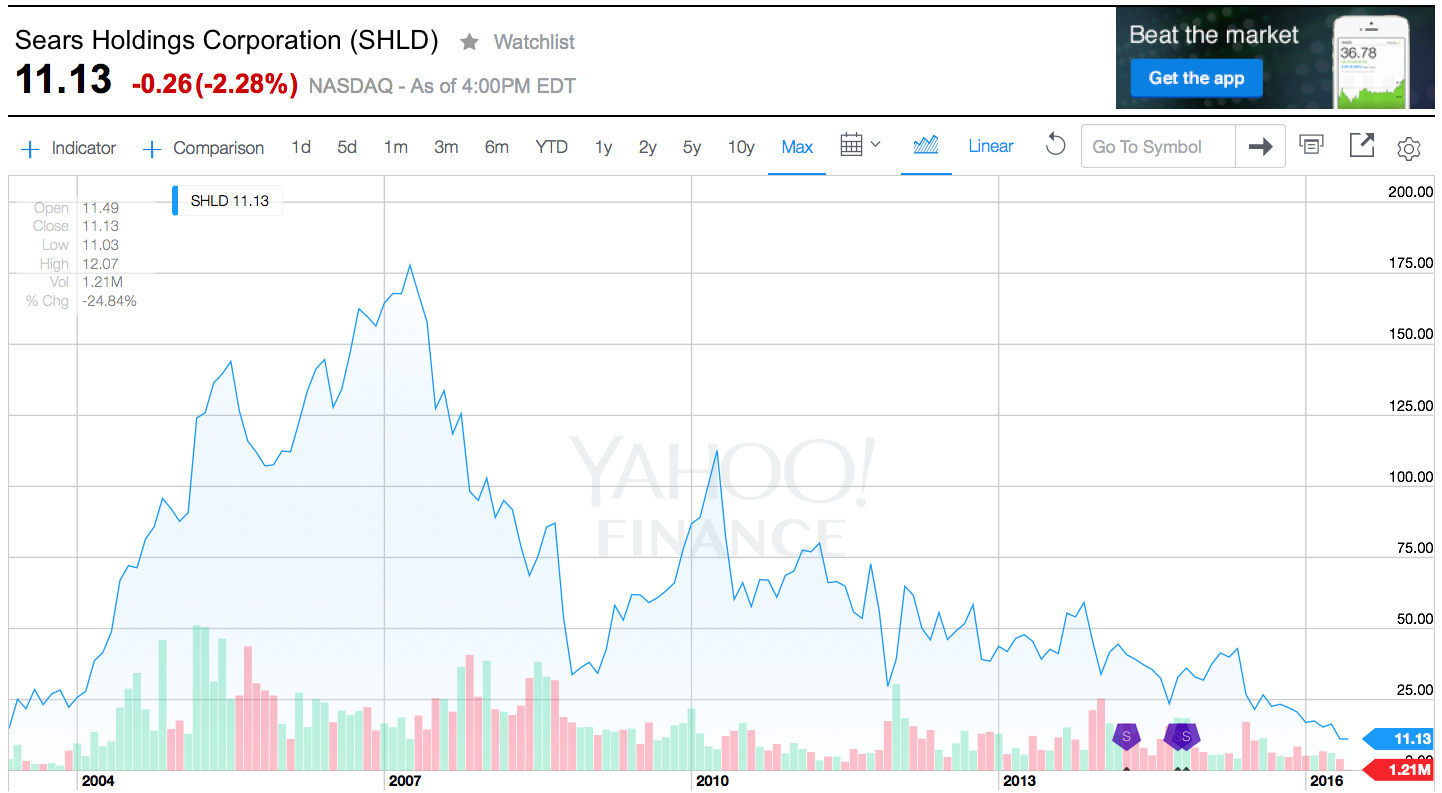

Last week Sears announced sales and earnings. And once again, the news was all bad. The stock closed at a record, all time low. One chart pretty much sums up the story, as investors are now realizing bankruptcy is the most likely outcome.

Chart Source: Yahoo Finance 5/13/16

Quick Rundown: In January, 2002 Kmart is headed for bankruptcy. Ed Lampert, CEO of hedge fund ESL, starts buying the bonds. He takes control of the company, makes himself Chairman, and rapidly moves through proceedings. On May 1, 2003, KMart begins trading again. The shares trade for just under $15 (for this column all prices are adjusted for any equity transactions, as reflected in the chart.)

Lampert quickly starts hacking away costs and closing stores. Revenues tumble, but so do costs, and earnings rise. By November, 2004 the stock has risen to $90. Lampert owns 53% of Kmart, and 15% of Sears. Lampert hires a new CEO for Kmart, and quickly announces his intention to buy all of slow growing, financially troubled Sears.

In March, 2005 Sears shareholders approve the deal. The stock trades for $126. Analysts praise the deal, saying Lampert has “the Midas touch” for cutting costs. Pumped by most analysts, and none moreso than Jim Cramer of “Mad Money” fame (Lampert’s former roommate,) in 2 years the stock soars to $178 by April, 2007. So far Lampert has done nothing to create value but relentlessly cut costs via massive layoffs, big inventory reductions, delayed payments to suppliers and store closures.

Homebuilding falls off a cliff as real estate values tumble, and the Great Recession begins. Retailers are creamed by investors, and appliance sales dependent Sears crashes to $33.76 in 18 months. On hopes that a recovering economy will raise all boats, the stock recovers over the next 18 months to $113 by April, 2010. But sales per store keep declining, even as the number of stores shrinks. Revenues fall faster than costs, and the stock falls to $43.73 by January, 2013 when Lampert appoints himself CEO. In just under 2.5 years with Lampert as CEO and Chairman the company’s sales keep falling, more stores are closed or sold, and the stock finds an all-time low of $11.13 – 25% lower than when Lampert took KMart public almost exactly 13 years ago – and 94% off its highs.

What happened?

Sears became a retailing juggernaut via innovation. When general stores were small and often far between, and stocking inventory was precious, Sears invented mail order catalogues. Over time almost every home in America was receiving 1, or several, catalogues every year. They were a major source of purchases, especially by people living in non-urban communities. Then Sears realized it could open massive stores to sell all those things in its catalogue, and the company pioneered very large, well stocked stores where customers could buy everything from clothes to tools to appliances to guns. As malls came along, Sears was again a pioneer “anchoring” many malls and obtaining lower cost space due to the company’s ability to draw in customers for other retailers.

To help customers buy more Sears created customer installment loans. If a young couple couldn’t afford a stove for their new home they could buy it on terms, paying $10 or $15 a month, long before credit cards existed. The more people bought on their revolving credit line, and the more they paid Sears, the more Sears increased their credit limit. Sears was the “go to” place for cash strapped consumers. (Eventually, this became what we now call the Discover card.)

In 1930 Sears expanded the Allstate tire line to include selling auto insurance – and consumers could not only maintain their car at Sears they could insure it as well. As its customers grew older and more wealthy, many needed help with financia advice so in 1981 Sears bought Dean Witter and made it possible for customers to figure out a retirement plan while waiting for their tires to be replaced and their car insurance to update.

To put it mildly, Sears was the most innovative retailer of all time. Until the internet came along. Focused on its big stores, and its breadth of products and services, Sears kept trying to sell more stuff through those stores, and to those same customers. Internet retailing seemed insignificantly small, and unappealing. Heck, leadership had discontinued the famous catalogues in 1993 to stop store cannibalization and push people into locations where the company could promote more products and services. Focusing on its core customers shopping in its core retail locations, Sears leadership simply ignored upstarts like Amazon.com and figured its old success formula would last forever.

But they were wrong. The traditional Sears market was niched up across big box retailers like Best Buy, clothiers like Kohls, tool stores like Home Depot, parts retailers like AutoZone, and soft goods stores like Bed, Bath & Beyond. The original need for “one stop shopping” had been overtaken by specialty retailers with wider selection, and often better pricing. And customers now had credit cards that worked in all stores. Meanwhile, for those who wanted to shop for many things from home the internet had taken over where the catalogue once began. Leaving Sears’ market “hollowed out.” While KMart was simply overwhelmed by the vast expansion of WalMart.

What should Lampert have done?

There was no way a cost cutting strategy would save KMart or Sears. All the trends were going against the company. Sears was destined to keep losing customers, and sales, unless it moved onto trends. Lampert needed to innovate. He needed to rapidly adopt the trends. Instead, he kept cutting costs. But revenues fell even faster, and the result was huge paper losses and an outpouring of cash.

To gain more insight, take a look at Jeff Bezos. But rather than harp on Amazon.com’s growth, look instead at the leadership he has provided to The Washington Post since acquiring it just over 2 years ago. Mr. Bezos did not try to be a better newspaper operator. He didn’t involve himself in editorial decisions. Nor did he focus on how to drive more subscriptions, or sell more advertising to traditional customers. None of those initiatives had helped any newspaper the last decade, and they wouldn’t help The Washington Post to become a more relevant, viable and profitable company. Newspapers are a dying business, and Bezos could not change that fact.

Mr. Bezos focused on trends, and what was needed to make The Washington Post grow. Media is under change, and that change is being created by technology. Streaming content, live content, user generated content, 24×7 content posting (vs. deadlines,) user response tracking, readers interactivity, social media connectivity, mobile access and mobile content — these are the trends impacting media today. So that was where he had leadership focus. The Washington Post had to transition from a “newspaper” company to a “media and technology company.”

So Mr. Bezos pushed for hiring more engineers – a lot more engineers – to build apps and tools for readers to interact with the company. And the use of modern media tools like headline testing. As a result, in October, 2015 The Washington Post had more unique web visitors than the vaunted New York Times. And its lead is growing. And while other newspapers are cutting staff, or going out of business, the Post is adding writers, editors and engineers. In a declining newspaper market The Washington Post is growing because it is using trends to transform itself into a company readers (and advertisers) value.

CEO Lampert could have chosen to transform Sears Holdings. But he did not. He became a very, very active “hands on” manager. He micro-managed costs, with no sense of important trends in retail. He kept trying to take cash out, when he needed to invest in transformation. He should have sold the real estate very early, sensing that retail was moving on-line. He should have sold outdated brands under intense competitive pressure, such as Kenmore, to a segment supplier like Best Buy. He then should have invested that money in technology. Sears should have been a leader in shopping apps, supplier storefronts, and direct-to-customer distribution. Focused entirely on defending Sears’ core, Lampert missed the market shift and destroyed all the value which initially existed in the great retail merger he created.

Impact?

Every company must understand critical trends, and how they will apply to their business. Nobody can hope to succeed by just protecting the core business, as it can be made obsolete very, very quickly. And nobody can hope to change a trend. It is more important than ever that organizations spend far less time focused on what they did, and spend a lot more time thinking about what they need to do next. Planning needs to shift from deep numerical analysis of the past, and a lot more in-depth discussion about technology trends and how they will impact their business in the next 1, 3 and 5 years.

Sears Holdings was a 13 year ride. Investor hope that Lampert could cut costs enough to make Sears and KMart profitable again drove the stock very high. But the reality that this strategy was impossible finally drove the value lower than when the journey started. The debacle has ruined 2 companies, thousands of employees’ careers, many shopping mall operators, many suppliers, many communities, and since 2007 thousands of investor’s gains. Four years up, then 9 years down. It happened a lot faster than anyone would have imagined in 2003 or 2004. But it did.

And it could happen to you. Invert your strategic planning time. Spend 80% on trends and scenario planning, and 20% on historical analysis. It might save your business.

by Adam Hartung | Feb 11, 2016 | Current Affairs, In the Whirlpool, Leadership, Lock-in

USAToday alerted investors that when Sears Holdings reports results 2/25/16 they will be horrible. Revenues down another 8.7% vs. last year. Same store sales down 7.1%. To deal with ongoing losses the company plans to close another 50 stores, and sell another $300million of assets. For most investors, employees and suppliers this report could easily be confused with many others the last few years, as the story is always the same. Back in January, 2014 CNBC headlined “Tracking the Slow Death of an Icon” as it listed all the things that went wrong for Sears in 2013 – and they have not changed two years later. The brand is now so tarnished that Sears Holdings is writing down the value of the Sears name by another $200million – reducing intangible value from the $4B at origination in 2004 to under $2B.

This has been quite the fall for Sears. When Chairman Ed Lampert fashioned the deal that had formerly bankrupt Kmart buying Sears in November, 2004 the company was valued at $11billion and 3,500 stores. Today the company is valued at $1.6billion (a decline of over 85%) and according to Reuters has just under 1,700 stores (a decline of 51%.) According to Bloomberg almost no analysts cover SHLD these days, but one who does (Greg Melich at Evercore ISI) says the company is no longer a viable business, and expects bankruptcy. Long-term Sears investors have suffered a horrible loss.

When I started business school in 1980 finance Professor Bill Fruhan introduced me to a concept that had never before occurred to me. Value Destruction. Through case analysis the good professor taught us that leadership could make decisions that increased company valuation. Or, they could make decisions that destroyed shareholder value. As obvious as this seems, at the time I could not imagine CEOs and their teams destroying shareholder value. It seemed anathema to the entire concept of business education. Yet, he quickly made it clear how easily misguided leaders could create really bad outcomes that seriously damaged investors.

As a case study in bad leadership, Sears under Chairman Lampert offers great lessons in Value Destruction that would serve Professor Fruhan’s teachings well:

As a case study in bad leadership, Sears under Chairman Lampert offers great lessons in Value Destruction that would serve Professor Fruhan’s teachings well:

1 – Micro-management in lieu of strategy. Mr. Lampert has been merciless in his tenacity to manage every detail at Sears. Daily morning phone calls with staff, and ridiculously tight controls that eliminate decision making by anyone other than the top officers. Additionally, every decision by the officers was questioned again and again. Explanations took precedent over action as micro-management ate up management’s time, rather than trying to run a successful company. While store employees and low- to mid-level managers could see competition – both traditional and on-line – eating away at Sears customers and core sales, they were helpless to do anything about it. Instead they were forced to follow orders given by people completely out of touch with retail trends and customer needs. Whatever chance Sears and Kmart had to grow the chain against intense competition it was lost by the Chairman’s need to micro-manage.

2 – Manage-by-the-numbers rather than trends. Mr. Lampert was a finance expert and former analyst turned hedge fund manager and investor. He truly believed that if he had enough numbers, and he studied them long enough, company success would ensue. Unfortunately, trends often are not reflected in “the numbers” until it is far, far too late to react. The trend to stores that were cleaner, and more hip with classier goods goes back before Lampert’s era, but he completely missed the trend that drove up sales at Target, H&M and even Kohl’s because he could not see that trend reflected in category sales or cost ratios. Merchandising – from buying to store layout and shelf positioning – are skills that go beyond numerical analysis but are critical to retail success. Additionally, the trend to on-line shopping goes back 20 years, but the direct impact on store sales was not obvious until customers had long ago converted. By focusing on numbers, rather than trends, Sears was constantly reacting rather than being proactive, and thus constantly retreating, cutting stores and cutting product lines.

3 – Seeking confirmation rather than disagreement. Mr. Lampert had no time for staff who did not see things his way. Mr. Lampert wanted his management team to agree with him – to confirm his Beliefs, Interpretations, Assumptions and Strategies — to believe his BIAS. By seeking managers who would confirm his views, and execute, rather than disagree Mr. Lampert had no one offering alternative data, interpretations, strategies or tactics. And, as Mr. Lampert’s plans kept faltering it led to a revolving door of managers. Leaders came and went in a year or two, blamed for failures that originated at the Chairman’s doorstep. By forcing agreement, rather than disagreement and dialogue, Sears lacked options or alternatives, and the company had no chance of turning around.

4 – Holding assets too long. In 2004 Sears had a LOT of assets. Many that could likely be redeployed at a gain for shareholders. Sears had many owned and leased store locations that were highly valuable with real estate prices climbing from then through 2008. But Mr. Lampert did not spin out that real estate in a REIT, capturing the value for SHLD shareholders while the timing was good. Instead he held those assets as real estate in general plummeted, and as retail real estate fell even further as more revenue shifted to e-commerce. By the time he was ready to sell his REIT much of the value was depleted.

Additionally, Sears had great brands in 2004. DieHard batteries, Craftsman tools, Kenmore appliances and Lands End apparel were just 4 household brands that still had high customer appeal and tremendous value. Mr. Lampert could have sold those brands to another retailer (such as selling DieHard to WalMart, for example) as their house brands, capturing that value. Or he could have mass marketd the brand beyond the Sears store to increase sales and value. Or he could have taken one or more brands on-line as a product leader and “category killer” for ecommerce customers. But he did not act on those options, and as Sears and Kmart stores faded, so did these brands – which largely no longer have any value. Had he sold when value was high there were profits to be made for investors.

5 – Hubris – unfailingly believing in oneself regardless the outcomes. In May, 2012 I wrote that Mr. Lampert was the 2nd worst CEO in America and should fire himself. This was not a comment made in jest. His initial plans had all panned out very badly, and he had no strategy for a turnaround. All results, from all programs implemented during his reign as Chairman had ended badly. Yet, despite these terrible numbers Mr. Lampert refused to recognize he was the wrong person in the wrong job. While it wasn’t clear if anyone could turn around the problems at Sears at such a late date, it was clear Mr. Lampert was not the person to do it. If Mr. Lampert had been as self-analytical as he was critical of others he would have long before replaced himself as the leader at Sears. But hubris would not allow him to do this, he remained blind to his own failings and the terrible outcome of a failed company was pretty much sealed.

From $11B valuation and a $92/share stock price at time of merging KMart and Sears, to a $1.6B valuation and a $15/share stock price. A loss of $9.4B (that’s BILLION DOLLARS). That is amazing value destruction. In a world where employees are fired every day for making mistakes that cost $1,000, $100 or even $10 it is a staggering loss created by Mr. Lampert. At the very least we should learn from his mistakes in order to educate better, value creating leaders.

by Adam Hartung | Apr 1, 2014 | Current Affairs, Defend & Extend, In the Swamp, Leadership, Web/Tech

“Hope springs eternal in the human breast” (Alexander Pope)

As it does for most investors. People do not like to accept the notion that a business will lose relevancy, and its value will fall. Especially really big companies that are household brand names. Investors, like customers, prefer to think large, established companies will continue to be around, and even do well. It makes everyone feel better to have a optimistic attitude about large, entrenched organizations.

And with such optimism investors have cheered Microsoft for the last 15 months. After a decade of trading up and down around $26/share, Microsoft stock has made a significant upward move to $41 – a new decade-long high. This price has people excited Microsoft will reach the dot.com/internet boom high of $60 in 2000.

After discovering that Windows 8, and the Surface tablet, were nowhere near reaching sales expectations after Christmas 2012 – and that PC sales were declining faster than expected – investors were cheered in 2013 to hear that CEO Steve Ballmer would resign. After much speculation, insider Satya Nadella was named CEO, and he quickly made it clear he was refocusing the company on mobile and cloud. This started the analysts, and investors, on their recent optimistic bent.

CEO Nadella has cut the price of Windows by 70% in order to keep hardware manufacturers on Windows for lower cost machines, and he announced the company’s #1 sales and profit product – Office – was being released on iOS for iPad users. Investors are happy to see this action, as they hope that it will keep PC sales humming. Or at least slow the decline in sales while keeping manufacturers (like HP) in the Microsoft Windows fold. And investors are likewise hopeful that the long awaited Office announcement will mean booming sales of Office 365 for all those Apple products in the installed base.

But, there’s a lot more needed for Microsoft to succeed than these announcements. While Microsoft is the world’s #1 software company, it is still under considerable threat and its long-term viability remains unsure.

Windows is in a tough spot. After this price decline, Microsoft will need to increase sales volume by 2.5X to recoup lost profits. Meanwhile, Chrome laptops are considerably cheaper for customers and more profitable for manufacturers. And whether this price cut will have any impact on the decline in PC sales is unclear, as users are switching to mobile products for ease-of-use reasons that go far beyond price. Microsoft has taken an action to defend and extend its installed base of manufacturers who have been threatening to move, but the impact on profits is still likely to be negative and PC sales are still going to decline.

Meanwhile, the move to offer Office on iOS is clearly another offer to defend the installed Office marketplace, and unlikely to create a lot of incremental revenue and profit growth. The PC market has long been much bigger than tablets, and almost every PC had Office installed. Shrinking at 12-14% means a lot less Windows Office is being sold. And, In tablets iOS is not 100% of the market, as Android has substantial share. Offering Office on iOS reaches a lot of potential machines, but certainly not 100% as has been the case with PCs.

Further, while there are folks who look forward to running Office on an iOS device, Office is not without competition. Both Apple and Google offer competitive products to Office, and the price is free. For price sensitive users, both individuals and corporations, after 4 years of using competitive products it is by no means a given they all are ready to pay $60-$100 per device per year. Yes, there will be Office sales Microsoft did not previously have, but whether it will be large enough to cover the declining sales of Office on the PC is far from clear. And whether current pricing is viable is far, far from certain.

While these Microsoft products are the easiest for consumers to understand, Nadella’s move to make Microsoft successful in the mobile/cloud world requires succeeding with cloud products sold to corporations and software-as-service providers. Here Microsoft is late, and facing substantial competition as well.

Just last week Google cut the price of its Compute Engine cloud infrastructure (IaaS) platform and App Engine cloud app platform (PaaS) products 30-32%. Google cut the price of its Cloud Storage and BigQuery (big data analytics) services by 68% and 85% as it competes headlong for customers with Amazon. Amazon, which has the first-mover position and large customers including the U.S. federal government, cut prices within 24 hours for its EC2 cloud computing service by 30%, and for its S3 storage service by over 50%. Amazon also reduced prices on its RDS database service approximately 28%, and its Elasticache caching service by over 33%.

To remain competitive, Microsoft had to react this week by chopping prices on its Azure cloud computing products 27%-35%, reducing cloud storage pricing 44%-65%, and whacking prices on its Windows and Linux memory-intensive computing products 27%-35%. While these products have allowed the networking division formerly run by now CEO Nadella to be profitable, it will be increasingly difficult to maintain old profit levels on existing customers, and even a tougher problem to profitably steal share from the early cloud leaders – even as the market grows.

While optimism has grown for Microsoft fans, and the share price has moved distinctly higher, it is smart to look at other market leaders who obtained investor favorability, only to quickly lose it.

Blackberry was known as RIM (Research in Motion) in June, 2007 when the iPhone was launched. RIM was the market leader, a near monopoly in smart phones, and its stock was riding high at $70. In August, 2007, on the back of its dominant status, the stock split – and moved on to a split adjusted $140 by end of 2008. But by 2010, as competition with iOS and Android took its toll RIM was back to $80 (and below.) Today the rechristened company trades for $8.

Sears was once the country’s largest and most successful retailer. By 2004 much of the luster was coming off when KMart purchased the company and took its name, trading at only $20/share. Following great enthusiasm for a new CEO (Ed Lampert) investors flocked to the stock, sure it would take advantage of historical brands such as DieHard, Kenmore and Craftsman, plus leverage its substantial real estate asset base. By 2007 the stock had risen to $180 (a 9x gain.) But competition was taking its toll on Sears, despite its great legacy, and sales/store started to decline, total sales started declining and profits turned to losses which began to stretch into 20 straight quarters of negative numbers. Meanwhile, demand for retail space declined, and prices declined, cutting the value of those historical assets. By 2009 the stock had dropped back to $40, and still trades around that value today — as some wonder if Sears can avoid bankruptcy.

Best Buy was a tremendous success in its early years, grew quickly and built a loyal customer base as the #1 retail electronics purveyor. But streaming video and music decimated CD and DVD sales. On-line retailers took a huge bite out of consumer electronic sales. By January, 2013 the stock traded at $13. A change of CEO, and promises of new formats and store revitalization propped up optimism amongst investors and by November, 2014 the stock was at $44. However, market trends – which had been in place for several years – did not change and as store sales lagged the stock dropped, today trading at only $25.

Microsoft has a great legacy. It’s products were market leaders. But the market has shifted – substantially. So far new management has only shown incremental efforts to defend its historical business with product extensions – which are up against tremendous competition that in these new markets have a tremendous lead. Microsoft so far is still losing money in on-line and gaming (xBox) where it has lost almost all its top leadership since 2014 began and has been forced to re-organize. Nadella has yet to show any new products that will create new markets in order to “turn the tide” of sales and profits that are under threat of eventual extinction by ever-more-capable mobile products.

While optimism springs eternal long-term investors would be smart to be skeptical about this recent improvement in the stock price. Things could easily go from mediocre to worse in these extremely competitive global tech markets, leaving Microsoft optimists with broken dreams, broken hearts and broken portfolios.

Update: On April 2 Microsoft announced it is providing Windows for free to all manufacturers with a 9″ or smaller display. This is an action to help keep Microsoft competitive in the mobile marketplace – but it does little for Microsoft profitability. Android from Google may be free, but Google’s business is built on ad sales – not software sales – and that’s dramatically different from Microsoft that relies almost entirely on Windows and Office for its profitability

Update: April 3 CRN (Computer Reseller News) reviewed Office products for iOS – “We predict that once the novelty of “Office for iPad” wears off, companies will go back to relying on the humble, hard-working third parties building apps that are as stable, as handsome and far more capable than those of Redmond. It’s not that hard to do.”

by Adam Hartung | Jul 18, 2013 | Current Affairs, Defend & Extend, In the Whirlpool, Leadership, Lock-in

Sears has performed horribly since acquired by Fast Eddie Lampert's KMart in 2005. Revenues are down 25%, same store sales have declined persistently, store margins have eroded and the company has recently taken to reporting losses. There really hasn't been any good news for Sears since the acquisition.

Bloomberg Businessweek made a frontal assault on CEO Edward Lampert's leadership at Sears this week. Over several pages the article details how a "free market" organization installed by Mr. Lampert led to rampant internal warfare and an inability for the company to move forward effectively with programs to improve sales or profits. Meanwhile customer satisfaction has declined, and formerly valuable brands such as Kenmore and Craftsman have become industry also-rans.

Because the Lampert controlled hedge fund ESL Investments is the largest investor in Sears, Mr. Lampert has no risk of being fired. Even if Nobel winner Paul Krugman blasts away at him. But, if performance has been so bad – for so long – why does the embattled Mr. Lampert continue to lead in the same way? Why doesn't he "fire" himself?

By all accounts Mr. Lampert is a very smart man. Yale summa cum laude and Phi Beta Kappa, he was a protege of former Treasury Secretay Robert Rubin at Goldman Sach before convincing billionaire Richard Rainwater to fund his start-up hedge fund – and quickly make himself the wealthiest citizen in Connecticut.

If the problems at Sears are so obvious to investors, industry analysts, economics professors, management gurus and journalists why doesn't he simply change?

Mr. Lampert, largely because of his success, is a victim of BIAS. Deep within his decision making are his closely held Beliefs, Interpretations, Assumptions and Strategies. These were created during his formative years in college and business. This BIAS was part of what drove his early success in Goldman, and ESL. This BIAS is now part of his success formula – an entire set of deeply held convictions about what works, and what doesn't, that are not addressed, discussed or even considered when Mr. Lampert and his team grind away daily trying to "fix" declining Sears Holdings.

This BIAS is so strong that not even failure challenges them. Mr. Lampert believes there is deep value in conventional retail, and real estate. He believes strongly in using "free market competition" to allocate resources. He believes in himself, and he believes he is adding value, even if nobody else can see it.

Mr. Lampert assumes that if he allows his managers to fight for resources, the best programs will reach the top (him) for resourcing. He assumes that the historical value in Sears and its house brands will remain, and he merely needs to unleash that value to a free market system for it to be captured. He assumes that because revenues remain around $35B Sears is not irrelevant to the retail landscape, and the company will be revitalized if just the right ideas bubble up from management.

Mr. Lampert inteprets the results very different from analysts. Where outsiders complain about revenue reductions overall and same store, he interprets this as an acceptable part of streamlining. When outsiders say that store closings and reduced labor hurt the brand, he interprets this as value-added cost savings. When losses appear as a result of downsizing he interprets this as short-term accounting that will not matter long-term. While most investors and analysts fret about the overall decline in sales and brands Mr. Lampert interprets growing sales of a small integrated retail program as a success that can turn around the sinking behemoth.

Mr. Lampert's strategy is to identify "deep value" and then tenaciously cut costs, including micro-managing senior staff with daily calls. He believes this worked for Warren Buffett, so he believes it will continue to be a successful strategy. Whether such deep value continues to exist – especially in conventional retail – can be challenged by outsiders (don't forget Buffett lost money on Pier 1,) but it is part of his core strategy and will not be challenged. Whether cost cutting does more harm than good is an unchallenged strategy. Whether micro-managing staff eats up precious resources and leads to unproductive behavior is a leadership strategy that will not change. Hiring younger employees, who resemble Mr. Lampert in quick thinking and intellect (if not industry knowledge or proven leadership skills) is a strategy that will be applied even as the revolving door at headquarters spins.

The retail market has changed dramatically, and incredibly quickly. Advances in internet shopping, technology for on-line shopping (from mobile devices to mobile payments) and rapid delivery have forever altered the economics of retailing. Customer ease of showrooming, and desire to shop remotely means conventional retail has shrunk, and will continue to shrink for several years. This means the real challenge for Sears is not to be a better Sears as it was in 2000 — but to become something very different that can compete with both WalMart and Amazon – and consumer goods manufacturers like GE (appliances) and Exide (car batteries.)

There is no doubt Mr. Lampert is a very smart person. He has made a fortune. But, he and Sears are a victim of his BIAS. Poor results, bad magazine articles and even customer complaints are no match for the BIAS so firmly underlying early success. Even though the market has changed, Mr. Lampert's BIAS has him (and his company) in internal turmoil, year after year, even though long ago outsiders gave up on expecting a better result.

Even if Sears Holdings someday finds itself in bankruptcy court, expect Mr. Lampert to interpret this as something other than a failure – as he defends his BIAS better than he defends its shareholders, employees, suppliers and customers.

What is your BIAS? Are you managing for the needs of changing markets, or working hard to defend doing more of what worked in a bygone era? As a leader, are you targeting the future, or trying to recapture the past? Have market shifts made your beliefs outdated, your interpretations of what happens around you faulty, your assumptions inaccurate and your strategies hurting results? If any of this is true, it may be time you address (and change) your BIAS, rather than continuing to invest in more of the same. Or you may well end up like Sears.

by Adam Hartung | May 12, 2012 | Current Affairs, Defend & Extend, In the Swamp, In the Whirlpool, Leadership, Web/Tech

This has been quite the week for CEO mistakes. First was all the hubbub about Scott Thompson, CEO of Yahoo, inflating his resume to include a computer science degree he did not actually receive. According to Mr. Thompson someone at a recruiting firm added that degree claim in 2005, he didn't know it and he's never read his bio since. A simple oversight, if you can believe he hasn't once read his bio in 7 years, and he didn't think it was ever important to correct someone who introduced him or mentioned it. OOPS – the easy answer for someone making several million dollars per year, and trying to guide a very troubled company from the brink of failure. Hopefully he is more persistent about checking company facts.

But luckily for him, his errors were trumped on Thursday when Jamie Dimon, CEO of J.P.MorganChase notified the world that the bank's hedging operation messed up and lost $2B!! OOPS! According to Mr. Dimon this is really no big deal. Which reminded me of the apocryphal Senator Everett Dirksen statement "a billion here, a billion there and pretty soon it all adds up to real money!"

Interesting "little" mistake from a guy who paid himself some $50M a few years ago, and benefitted greatly from the government TARP program. He said this would be "fodder for pundits," as if we all should simply overlook losing $2B? He also said this was "unfortunate timing." As if there's a good time to lose $2B?

But neither of these problems will likely result in the CEOs losing their jobs. As obviously damaging as both mistakes are, which would naturally have caused us mere employees to instantly lose our jobs – and potentially be prosecuted – CEOs are a rare breed who are allowed wide lattitude in their behavior. These are "one off" events that gain a lot of attention, but the media will have forgotten within a few days, and everyone else within a few months.

By comparison, there are at least 5 CEOs that make these 2 mistakes appear pretty small. For these 5, frequently honored for their position, control of resources and personal wealth, they are doing horrific damage to their companies, hurting investors, employees, suppliers and the communities that rely on their organizations. They should have been fired long before this week.

#5 – John Chambers, Cisco Systems. Mr. Chambers is the longest serving CEO on this list, having led Cisco since 1995 and championed much of its rapid growth as corporations around the world began installing networks. Cisco's stock reached $70/share in 2001. But since then a combination of recessions that cut corporate IT budgets and a market shift to cloud computing has left Cisco scrambling for a strategy, and growth.

Mr. Chambers appears to have been great at operating Cisco as long as he was in a growth market. But since customers turned to cloud computing and greater use of mobile telephony networks Cisco has been unable to innovate, launch and grow new markets for cloud storage, services or applications. Mr. Chambers has reorganized the company 3 times – but it has been much like rearranging the deck chairs on the Titanic. Lots of confusion, but no improvement in results.

Between 2001 and 2007 the stock lost half its value, falling to $35. Continuing its slide, since 2007 the stock has halved again, now trading around $17. And there is no sign of new life for Cisco – as each earnings call reinforces a company lacking a strategy in a shifting market. If ever there was a need for replacing a stayed-in-the-job too long CEO it would be Cisco.

#4 – Jeffrey Immelt, General Electric (GE). GE has only had 9 CEOs in its 100+ year life. But this last one has been a doozy. After more than a decade of rapid growth in revenue, profits and valuation under the disruptive "neutron" Jack Welch, GE stock reached $60 in 2000. Which turns out to have been the peak, as GE's value has gone nowhere but down since Mr. Immelt took the top job.

GE was once known for entering and changing markets, unafraid to disrupt how the market performed with innovation in products, supply chain and operations. There was no market too distant, or too locked-in for GE to not find a way to change to its advantage – and profit. But what was the last market we saw GE develop? What has Mr. Immelt, in his decade at the top of GE, done to keep GE as one of the world's most innovative, high growth companies? He has steered the ship away from trouble, but it's only gone in circles as it's used up fuel.

From that high in 2001, GE fell to a low of $8 in 2009 as the financial crisis revealed that under Mr. Immelt GE had largely transitioned from a manufacturing and products company into a financial house. He had taken what was then the easy road to managing money, rather than managing a products and services company. Saved from bankruptcy by a lucrative Berkshire Hathaway, GE lived on. But it's stock is still only $19, down 2/3 from when Mr. Immelt took the CEO position.

"Stewardship" is insufficient leadership in 2012. Today markets shift rapidly, incur intensive global competition and require constant innovation. Mr. Immelt has no vision to propel GE's growth, and should have been gone by 2010, rather than allowed to muddle along with middling performance.

#3 – Mike Duke, WalMart. Mr. Duke has been CEO since 2009, but prior to that he was head of WalMart International. We now know Mr. Duke's business unit saw no problems with bribing foreign officials to grow its business. Just on the basis of knowing about illegal activity, not doing anything about it (and probably condoning and recommending more,) and then trying to change U.S. law to diminish the legal repurcussions, Mr. Duke should have long ago been fired.

It's clear that internally the company and its Board new Mr. Duke was willing to do anything to try and grow WalMart, even if unethical and potentially illegal. Recollections of Enron's Jeff Skilling, Worldcom's Bernie Ebbers and Hollinger's Conrdad Black should be in our heads. How far do we allow leaders to go before holding them accountable?

But worse, not even bribes will save WalMart as Mr. Duke follows a worn-out strategy unfit for competition in 2012. The entire retail market is shifting, with much lower cost on-line companies offering more selection at lower prices. And increasingly these companies are pioneering new technologies to accelerate on-line shopping with easy to use mobile devices, and new apps that make shopping, paying and tracking deliveries easier all the time. But WalMart has largely eschewed the on-line world as its CEO has doggedly sticks with WalMart doing more of the same. That pursuit has limited WalMart's growth, and margins, while the company files further behind competitively.

Unfortunately, WalMart peaked at about $70 in 2000, and has been flat ever since. Investors have gained nothing from this strategy, while employees often work for wages that leave them on the poverty line and without benefits. Scandals across all management layers are embarrassing. Communities find Walmart a mixed bag, initially lowering prices on some goods, but inevitably gutting the local retailers and leaving the community with no local market suppliers. WalMart needs an entirely new strategy to remain viable – and that will not come from Mr. Duke. He should have been gone long before the recent scandal, and surely now.

#2 Edward Lampert, Sears Holdings. OK, Mr. Lampert is the Chairman and not the CEO – but there is no doubt who calls the shots at Sears. And as Mr. Lampert has called the shots, nobody has gained.

Once the most critical force in retailing, since Mr. Lampert took over Sears has become wholly irrelevant. Hoping that Mr. Lampert could make hay out of the vast real estate holdings, and once glorious brands Craftsman, Kenmore and Diehard to turn around the struggling giant, the stock initially took off rising from $30 in 2004 to $170 in 2007 as Jim Cramer of "Mad Money" fame flogged the stock over and over on his rant-a-thon show. But when it was clear results were constantly worsening, as revenues and same-store-sales kept declining, the stock fell out of bed dropping into the $30s in 2009 and again in 2012.

Hope springs eternal in the micro-managing Mr. Lampert. Everyone knows of his personal fortune (#367 on Forbes list of billionaires.) But Mr. Lampert has destroyed Sears. The company may already be so far gone as to be unsavable. The stock price is based upon speculation of asset sales. Mr. Lampert had no idea, from the beginning, how to create value from Sears and he surely should have been gone many months ago as the hyped expectations demonstrably never happened.

#1 – Steve Ballmer, Microsoft. Without a doubt, Mr. Ballmer is the worst CEO of a large publicly traded American company. Not only has he singlehandedly steered Microsoft out of some of the fastest growing and most lucrative tech markets (mobile music, handsets and tablets) but in the process he has sacrificed the growth and profits of not only his company but "ecosystem" companies such as Dell, Hewlett Packard and even Nokia. The reach of his bad leadership has extended far beyond Microsoft when it comes to destroying shareholder value – and jobs.

Microsoft peaked at $60/share in 2000, just as Mr. Ballmer took the reigns. By 2002 it had fallen into the $20s, and has only rarely made it back to its current low $30s value. And no wonder, since execution of new rollouts were constantly delayed, and ended up with products so lacking in any enhanced value that they left customers scrambling to find ways to avoid upgrades. By Mr. Ballmer's own admission Vista had over 200 man-years too much cost, and its launch still, years late, has users avoiding upgrades. Microsoft 7 and Office 2012 did nothing to excite tech users, in corporations or at home, as Apple took the leadership position in personal technology.

So today Microsoft, after dumping Zune, dumping its tablet, dumping Windows CE and other mobile products, is still the same company Mr. Ballmer took control over a decade ago. Microsoft is PC company, nothing more, as demand for PCs shifts to mobile. Years late to market, he has bet the company on Windows 8 – as well as the future of Dell, HP, Nokia and others. An insane bet for any CEO – and one that would have been avoided entirely had the Microsoft Board replaced Mr. Ballmer years ago with a CEO that understands the fast pace of technology shifts and would have kept Microsoft current with market trends.

Although he's #19 on Forbes list of billionaires, Mr. Ballmer should not be allowed to take such incredible risks with investor money and employee jobs. Best he be retired to enjoy his fortune rather than deprive investors and employees of building theirs.

There were a lot of notable CEO changes already in 2012. Research in Motion, Best Buy and American Airlines are just three examples. But the 5 CEOs in this column are well on the way to leading their companies into the kind of problems those 3 have already discovered. Hopefully the Boards will start to pay closer attention, and take action before things worsen.

As a case study in bad leadership, Sears under Chairman Lampert offers great lessons in Value Destruction that would serve Professor Fruhan’s teachings well:

As a case study in bad leadership, Sears under Chairman Lampert offers great lessons in Value Destruction that would serve Professor Fruhan’s teachings well: