by Adam Hartung | Jul 11, 2018 | Computing, Growth Stall, Innovation, Investing, Software

The last few quarters sales growth has not been as good for Apple as it once was. The iPhone X didn’t sell as fast as they hoped, and while the Apple Watch outsells the entire Swiss watch industry it does not generate the volumes of an iPhone. And other new products like Apple Pay and iBeacon just have not taken off.

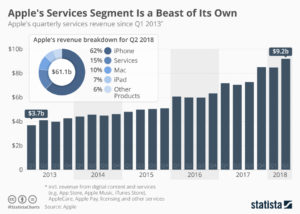

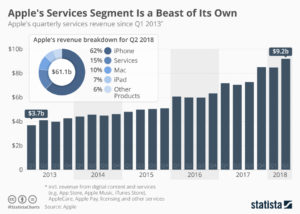

Amidst this slowness, the big winner has been “Apple Services” revenue. This is largely sales of music, videos and apps from iTunes and the App store. In Q2, 2018 revenues reached $9.2B, 15% of total revenues and second only to iPhone sales. Although Apple does not have a majority of smartphone users, the user base it has spends a lot of money on things for Apple devices. A lot of money.

In a bit of “get them the razor so they will buy the razor blades” CEO Tim Cook’s Apple is increasingly relying upon farming the “installed base” of users to drive additional revenues. Leveraging the “installed base” of users is now THE primary theme for growing Apple sales. And even old-tech guys like Warren Buffett at Berkshire Hathaway love it, as they gobble up Apple shares. As do many analysts, and investors. Apple has paid out over $100B to developers for its services, and generated over $40B in revenues for itself – and with such a large base willing to buy things developers are likely to keep providing more products and working to grow sales.

In a bit of “get them the razor so they will buy the razor blades” CEO Tim Cook’s Apple is increasingly relying upon farming the “installed base” of users to drive additional revenues. Leveraging the “installed base” of users is now THE primary theme for growing Apple sales. And even old-tech guys like Warren Buffett at Berkshire Hathaway love it, as they gobble up Apple shares. As do many analysts, and investors. Apple has paid out over $100B to developers for its services, and generated over $40B in revenues for itself – and with such a large base willing to buy things developers are likely to keep providing more products and working to grow sales.

But the risks here should not be taken lightly. At one time Apple’s Macintosh was the #1 selling PC. But it was “closed” and required users buy their applications from Apple. Microsoft offered its “open architecture” and suddenly lots of new applications were available for PCs, which were also cheaper than Macs. Over a few years that “installed base” strategy backfired for Apple as PC sales exploded and Mac sales shrank until it became a niche product with under 10% market share.

Today, Android phones are the #1 smartphone market share platform, and Android devices (like the PC) are much cheaper. Even cheaper are Chinese made products. Although there are problems, the risk exists that someday apps, etc for Android and/or other platforms could become more standard and the larger Android base could “flip” the market.

The history of companies relying on an installed base to grow their company has not gone well. Going back 30 years, AM Multigraphics an ABDick sold small printing presses to schools, government agencies and businesses. After the equipment sale these companies made most of their growth on the printing supplies these presses used. But competitors whacked away at those sales, and eventually new technologies displaced the small presses. The installed base shrank, and both companies disappeared.

Xerox would literally give companies a copier if they would just pay a “per click” charge for service on the machine, and use Xerox toner. Xerox grew like the proverbial weed. Their service and toner revenue built the company. But then people started using much cheaper copiers they could buy, and supply with cheaper consumables. And desktop publishing solutions caused copier use to decline. So much for Xerox growth – and the company rapidly lost relevance. Now Xerox is on the verge of disappearing into Fuji.

HP loved to sell customers cheap ink-jet printer so they bought the ink. But now images are mostly transferred as .jpg, .png or .pdf files and not printed at all. The installed base of HP printers drove growth, until the need for any printing started disappearing.

The point? It is very risky to rely on your installed platform base for your growth. Why? Because competitors with cheaper platforms can come along and offer cheaper consumables, making your expensive platform hard to keep forefront in the market. That’s the classic “innovator’s dilemma” – someone comes along with a less-good solution but it’s cheaper and people say “that’s good enough” thus switching to the cheaper platform. This leaves the innovator stuck trying to defend their expensive platform and aftermarket sales as the market switches to ever better, cheaper solutions.

It’s great that Apple is milking its installed base. That’s smart. But it is not a viable long-term strategy. That base will, someday, be overtaken by a competitor or a new technology. Like, maybe, smart speakers. They are becoming ubiquitous. Yes, today Siri is the #1 voice assistant. But as Echo and Google speaker sales proliferate, can they do to smartphones what smartphones did to PCs? What if one of these companies cooperates with Microsoft to incorporate Cortana, and link everything on the network into the Windows infrastructure? If these scenarios prevail, Apple could/will be in big trouble.

I pointed out in October, 2016 that Apple hit a Growth Stall. When that happens, maintaining 2% growth long-term happens only 7% of the time. I warned investors to be wary of Apple. Why? Because a Growth Stall is an early indicator of an innovation gap developing between the company’s products and emerging products. In this case, it could be a gap between ever enhanced (beyond user needs) mobile devices and really cheap voice activated assistant devices in homes, cars, offices, everywhere. Apple can milk that installed base for a goodly while, but eventually it needs “the next big thing” if it is going to continue being a long-term winner.

by Adam Hartung | May 10, 2016 | Defend & Extend, In the Swamp, Leadership, Lifecycle, Web/Tech

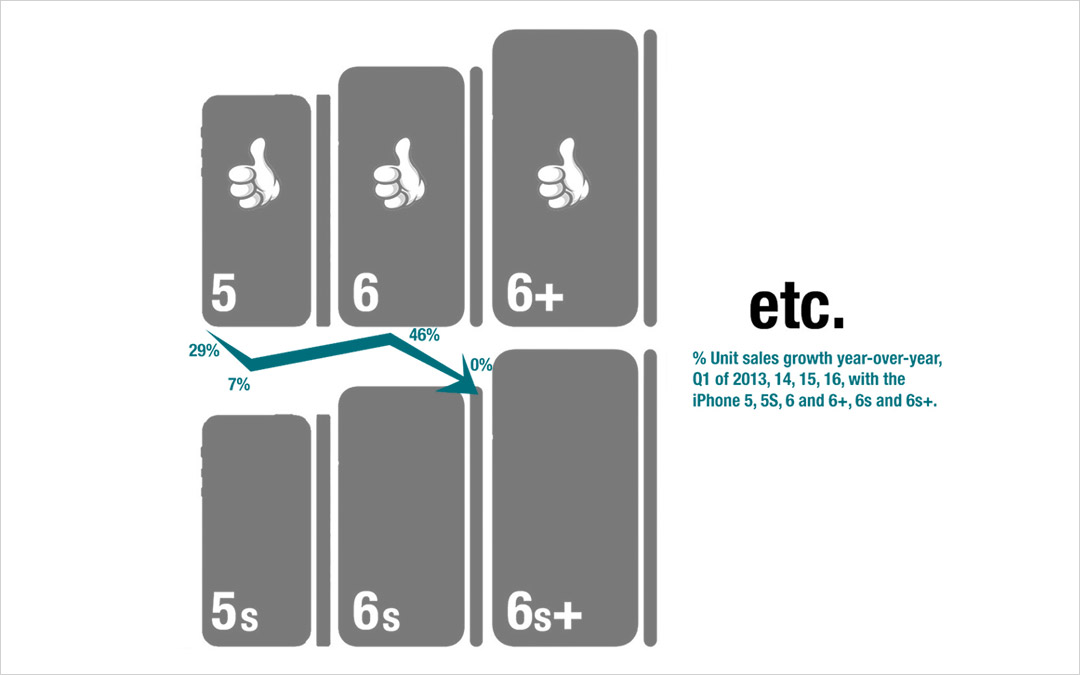

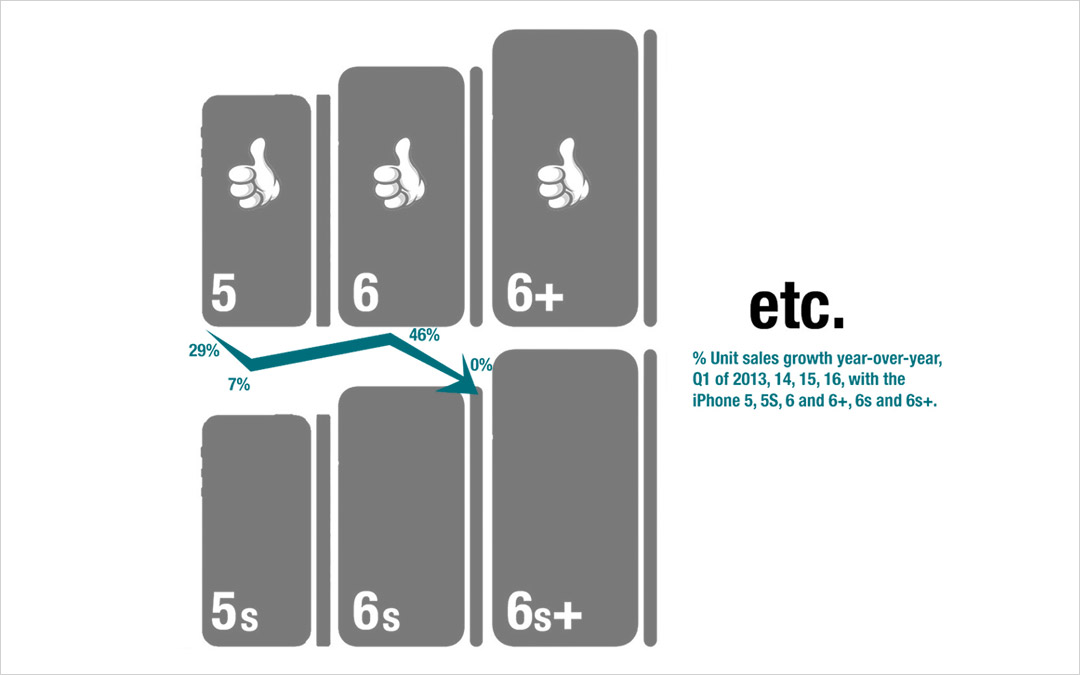

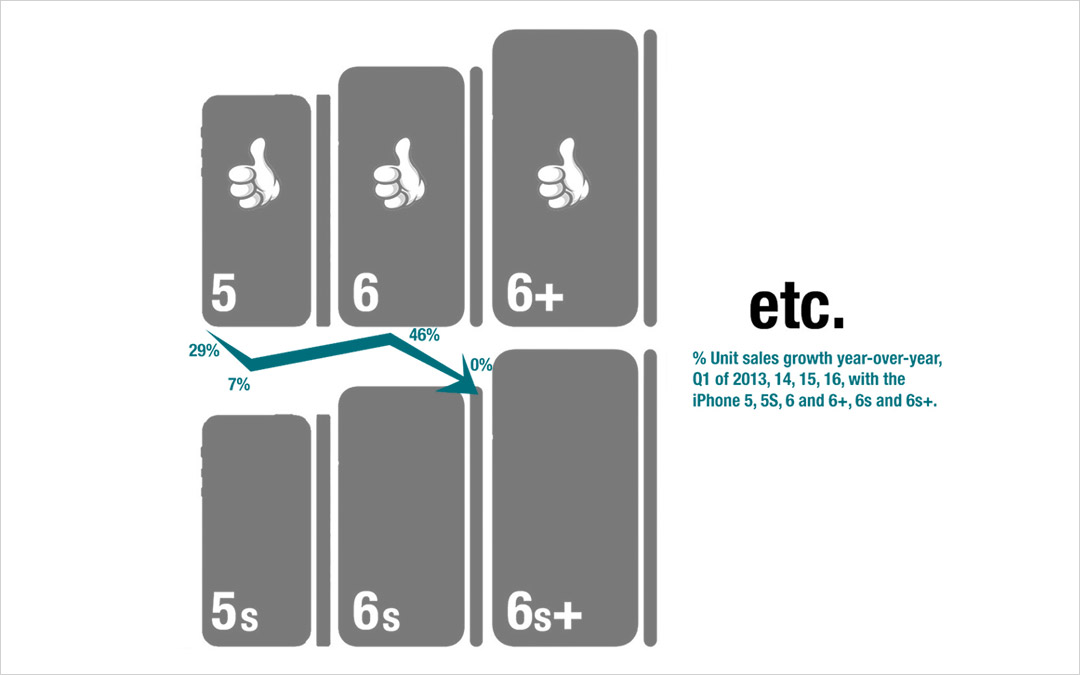

My last column focused on growth, and the risks inherent in a Growth stall. As I mentioned then, Apple will enter a Growth Stall if its revenue declines year-over-year in the current quarter. This forecasts Apple has only a 7% probability of consistently growing just 2%/year in the future.

This usually happens when a company falls into Defend & Extend (D&E) management. D&E management is when the bulk of management attention, and resources, flow into protecting the “core” business by seeking ways to use sustaining innovations (rather than disruptive innovations) to defend current customers and extend into new markets. Unfortunately, this rarely leads to high growth rates, and more often leads to compressed margins as growth stalls. Instead of working on breakout performance products, efforts are focused on ways to make new versions of old products that are marginally better, faster or cheaper.

Using the D&E lens, we can identify what looks like a sea change in Apple’s strategy.

Using the D&E lens, we can identify what looks like a sea change in Apple’s strategy.

For example, Apple’s CEO has trumpeted the company’s installed base of 1B iPhones, and stated they will be a future money maker. He bragged about the 20% growth in “services,” which are iPhone users taking advantage of Apple Music, iCloud storage, Apps and iTunes. This shows management’s desire to extend sales to its “installed base” with sustaining software innovations. Unfortunately, this 20% growth was a whopping $1.2B last quarter, which was 2.4% of revenues. Not nearly enough to make up for the decline in “core” iPhone, iPad or Mac sales of approximately $9.5B.

Apple has also been talking a lot about selling in China and India. Unfortunately, plans for selling in India were at least delayed, if not thwarted, by a decision on the part of India’s regulators to not allow Apple to sell low cost refurbished iPhones in the country. Fearing this was a cheap way to dispose of e-waste they are pushing Apple to develop a low-cost new iPhone for their market. Either tactic, selling the refurbished products or creating a cheaper version, are efforts at extending the “core” product sales at lower margins, in an effort to defend the historical iPhone business. Neither creates a superior product with new features, functions or benefits – but rather sustains traditional product sales.

Of even greater note was last week’s announcement that Apple inked a partnership with SAP to develop uses for iPhones and iPads built on the SAP ERP (Enterprise Resource Planning) platform. This announcement revealed that SAP would ask developers on its platform to program in Swift in order to support iOS devices, rather than having a PC-first mentality.

This announcement builds on last year’s similar announcement with IBM. Now 2 very large enterprise players are building applications on iOS devices. This extends the iPhone, a product long thought of as great for consumers, deeply into enterprise sales. A market long dominated by Microsoft. With these partnerships Apple is growing its developer community, while circumventing Microsoft’s long-held domain, promoting sales to companies as well as individuals.

And Apple has shown a willingness to help grow this market by introducing the iPhone 6se which is smaller and cheaper in order to obtain more traction with corporate buyers and corporate employees who have been iPhone resistant. This is a classic market extension intended to sustain sales with more applications while making no significant improvements in the “core” product itself.

And Apple’s CEO has said he intends to make more acquisitions – which will surely be done to shore up weaknesses in existing products and extend into new markets. Although Apple has over $200M of cash it can use for acquisitions, unfortunately this tactic can be a very difficult way to actually find new growth. Each would be targeted at some sort of market extension, but like Beats the impact can be hard to find.

Remember, after all revenue gains and losses were summed, Apple’s revenue fell $7.6B last quarter. Let’s look at some favorite analyst acquisition targets to explain:

- Box could be a great acquisition to help bring more enterprise developers to Apple. Box is widely used by enterprises today, and would help grow where iCloud is weak. IBM has already partnered with Box, and is working on applications in areas like financial services. Box is valued at $1.45B, so easily affordable. But it also has only $300M of annual revenue. Clearly Apple would have to unleash an enormous development program to have Box make any meaningful impact in a company with over $500B of revenue. Something akin of Instagram’s growth for Facebook would be required. But where Instagram made Facebook a pic (versus words) site, it is unclear what major change Box would bring to Apple’s product lines.

- Fitbit is considered a good buy in order to put some glamour and growth onto iWatch. Of course, iWatch already had first year sales that exceeded iPhone sales in its first year. But Apple is now so big that all numbers have to be much bigger in order to make any difference. With a valuation of $3.7B Apple could easily afford FitBit. But FitBit has only $1.9B revenue. Given that they are different technologies, it is unclear how FitBit drives iWatch growth in any meaningful way – even if Apple converted 100% of Fitbit users to the iWatch. There would need to be a “killer app” in development at FitBit that would drive $10B-$20B additional annual revenue very quickly for it to have any meaningful impact on Apple.

- GoPro is seen as a way to kick up Apple’s photography capabilities in order to make the iPhone more valuable – or perhaps developing product extensions to drive greater revenue. At a $1.45B valuation, again easily affordable. But with only $1.6B revenue there’s just not much oomph to the Apple top line. Even maximum Apple Store distribution would probably not make an enormous impact. It would take finding some new markets in industry (enterprise) to build on things like IoT to make this a growth engine – but nobody has said GoPro or Apple have any innovations in that direction. And when Amazon tried to build on fancy photography capability with its FirePhone the product was a flop.

- Tesla is seen as the savior for the Apple Car – even though nobody really knows what the latter is supposed to be. Never mind the actual business proposition, some just think Elon Musk is the perfect replacement for the late Steve Jobs. After all the excitement for its products, Tesla is valued at only $28.4B, so again easily affordable by Apple. And the thinking is that Apple would have plenty of cash to invest in much faster growth — although Apple doesn’t invest in manufacturing and has been the king of outsourcing when it comes to actually making its products. But unfortunately, Tesla has only $4B revenue – so even a rapid doubling of Tesla shipments would yield a mere 1.6% increase in Apple’s revenues.

- In a spree, Apple could buy all 4 companies! Current market value is $35B, so even including a market premium $55B-$60B should bring in the lot. There would still be plenty of cash in the bank for growth. But, realize this would add only $8B of annual revenue to the current run rate – barely 25% of what was needed to cover the gap last quarter – and less than 2% incremental growth to the new lower run rate (that magic growth percentage to pull out of a Growth Stall mentioned earlier in this column.)

Such acquisitions would also be problematic because all have P/E (price/earnings) ratios far higher than Apple’s 10.4. FitBit is 24, GoPro is 43, and both Box and Tesla are infinite because they lose money. So all would have a negative impact on earnings per share, which theoretically should lower Apple’s P/E even more.

Acquisitions get the blood pumping for investment bankers and media folks alike – but, truthfully, it is very hard to see an acquisition path that solves Apple’s revenue problem.

All of Apple’s efforts big efforts today are around sustaining innovations to defend & extend current products. No longer do we hear about gee whiz innovations, nor do we hear about growth in market changing products like iBeacons or ApplePay. Today’s discussions are how to rejuvenate sales of products that are several versions old. This may work. Sales may recover via growth in India, or a big pick-up in enterprise as people leave their PCs behind. It could happen, and Apple could avoid its Growth Stall.

But investors have the right to be concerned. Apple can grow by defending and extending the iPhone market only so long. This strategy will certainly affect future margins as prices, on average, decline. In short, investors need to know what will be Apple’s next “big thing,” and when it is likely to emerge. It will take something quite significant for Apple to maintain it’s revenue, and profit, growth.

The good news is that Apple does sell for a lowly P/E of 10 today. That is incredibly low for a company as profitable as Apple, with such a large installed base and so many market extensions – even if its growth has stalled. Even if Apple is caught in the Innovator’s Dilemma (i.e. Clayton Christensen) and shifting its strategy to defending and extending, it is very lowly valued. So the stock could continue to perform well. It just may never reach the P/E of 15 or 20 that is common for its industry peers, and investors envisioned 2 or 3 years ago. Unless there is some new, disruptive innovation in the pipeline not yet revealed to investors.

by Adam Hartung | Aug 6, 2014 | Defend & Extend, In the Whirlpool, Innovation, Lifecycle, Web/Tech

Remember the RAZR phone? Whatever happened to that company?

Motorola has a great tradition. Motorola pioneered the development of wireless communications, and was once a leader in all things radio – as well as made TVs. In an earlier era Motorola was the company that provided 2-way radios (and walkie-talkies for those old enough to remember them) not only for the military, police and fire departments, but connected taxies to dispatchers, and businesses from electricians to plumbers to their “home office.”

Motorola was the company that developed not only the thing in a customer’s hand, but the base stations in offices and even the towers (and equipment on those towers) to allow for wireless communication to work. Motorola even invented mobile telephony, developing the cellular infrastructure as well as the mobile devices. And, for many years, Motorola was the market share leader in cellular phones, first with analog phones and later with digital phones like the RAZR.

But that was the former Motorola, not the renamed Motorola Solutions of today. The last few years most news about Motorola has been about layoffs, downsizings, cost reductions, real estate sales, seeking tenants for underused buildings and now looking for a real estate partner to help the company find a use for its dramatically under-utilized corporate headquarters campus in suburban Chicago.

How did Motorola Solutions become a mere shell of its former self?

Unfortunately, several years ago Motorola was a victim of disruptive innovation, and leadership reacted by deciding to “focus” on its “core” markets. Focus and core are two words often used by leadership when they don’t know what to do next. Too often investment analysts like the sound of these two words, and trumpet management’s decision – knowing that the code implies cost reductions to prop up profits.

But smart investors know that the real implication of “focusing on our core” is the company will soon lose relevancy as markets advance. This will lead to significant sales declines, margin compression, draconian actions to create short-term P&L benefits and eventually the company will disappear.

Motorola’s market decline started when Blackberry used its server software to help corporations more securely use mobile devices for instant communications. The mobile phone transitioned from a consumer device to a business device, and Blackberry quickly grabbed market share as Motorola focused on trying to defend RAZR sales with price reductions while extending the RAZR platform with new gimmicks like additional colors for cases, and adding an MP3 player (called the ROKR.) The Blackberry was a game changer for mobile phones, and Motorola missed this disruptive innovation as it focused on trying to make sustaining improvements in its historical products.

Of course, it did not take long before Apple brought out the iPhone and with all those thousands of apps changed the game on Blackberry. This left Motorola completely out of the market, and the company abandoned its old platform hoping it could use Google’s Android to get back in the game. But, unfortunately, Motorola brought nothing really new to users and its market share dropped to nearly nothing.

The mobile phone business quickly overtook much of the old Motorola 2-way radio business. No electrician or plumber, or any other business person, needed the old-fashioned radios upon which Motorola built its original business. Even police officers used mobile phones for much of their communication, making the demand for those old-style devices rarer with each passing quarter.

But rather than develop a new game changer that would make it once again competitive, Motorola decided to split the company into 2 parts. One would be the very old, and diminishing, radio business still sold to government agencies and niche business applications. This business was profitable, if shrinking. The reason was so that leadership could “focus” on this historical “core” market. Even if it was rapidly becoming obsolete.

The mobile phone business was put out on its own, and lacking anything more than an historical patent portfolio, with no relevant market position, it racked up quarter after quarter of losses. Lacking any innovation to change the market, and desperate to get rid of the losses, in 2011 Motorola sold the mobile phone business – formerly the industry creator and dominant supplier – to Google. Again, the claim was this would allow leadership to even better “focus” on its historical “core” markets.

But the money from the Google sale was invested in trying to defend that old market, which is clearly headed for obsolescence. Profit pressures intensify every quarter as sales are harder to find when people have alternative solutions available from ever improving mobile technology.

As the historical market continued to weaken, and leadership learned it had under-invested in innovation while overspending to try to defend aging solutions, Motorola again cut the business substantially by selling a chunk of its assets – called its “enterprise business” – to a much smaller Zebra Technologies. The ostensible benefit was it would now allow Motorola leadership to even further “focus” on its ever smaller “core” business in government and niche market sales of aging radio technology.

But, of course, this ongoing “focus” on its “core” has failed to produce any revenue growth. So the company has been forced to undertake wave after wave of layoffs. As buildings empty they go for lease, or sale. And nobody cares, any longer, about Motorola. There are no news articles about new products, or new innovations, or new markets. Motorola has lost all market relevancy as its leaders used “focus” on its “core” business to decimate the company’s R&D, product development, sales and employment.

Retrenchment to focus on a core market is not a strategy which can benefit shareholders, customers, employees or the community in which a business operates. It is an admission that the leaders missed a major market shift, and have no idea how to respond. It is the language adopted by leaders that lack any vision of how to grow, lack any innovation, and are quickly going to reduce the company to insignificance. It is the first step on the road to irrelevancy.

Straight from Dr. Christensen’s “Innovator’s Dilemma” we now have another brand name to add to the list of those which were once great and meaningful, but now are relegated to Wikipedia historical memorabilia – victims of their inability to react to disruptive innovations while trying to sustain aging market positions – Motorola, Sears, Montgomery Wards, Circuit City, Sony, Compaq, DEC, American Motors, Coleman, Piper, Sara Lee………..

by Adam Hartung | Jun 28, 2013 | Current Affairs, Defend & Extend, In the Rapids, In the Whirlpool, Innovation, Leadership, Web/Tech

The last 12 months Tesla Motors stock has been on a tear. From $25 it has more than quadrupled to over $100. And most analysts still recommend owning the stock, even though the company has never made a net profit.

There is no doubt that each of the major car companies has more money, engineers, other resources and industry experience than Tesla. Yet, Tesla has been able to capture the attention of more buyers. Through May of 2013 the Tesla Model S has outsold every other electric car – even though at $70,000 it is over twice the price of competitors!

During the Bush administration the Department of Energy awarded loans via the Advanced Technology Vehicle Manufacturing Program to Ford ($5.9B), Nissan ($1.4B), Fiskar ($529M) and Tesla ($465M.) And even though the most recent Republican Presidential candidate, Mitt Romney, called Tesla a "loser," it is the only auto company to have repaid its loan. And did so some 9 years early! Even paying a $26M early payment penalty!

How could a start-up company do so well competing against companies with much greater resources?

Firstly, never underestimate the ability of a large, entrenched competitor to ignore a profitable new opportunity. Especially when that opportunity is outside its "core."

A year ago when auto companies were giving huge discounts to sell cars in a weak market I pointed out that Tesla had a significant backlog and was changing the industry. Long-time, outspoken industry executive Bob Lutz – who personally shepharded the Chevy Volt electric into the market – was so incensed that he wrote his own blog saying that it was nonsense to consider Tesla an industry changer. He predicted Tesla would make little difference, and eventually fail.

For the big car companies electric cars, at 32,700 units January thru May, represent less than 2% of the market. To them these cars are simply not seen as important. So what if the Tesla Model S (8.8k units) outsold the Nissan Leaf (7.6k units) and Chevy Volt (7.1k units)? These bigger companies are focusing on their core petroleum powered car business. Electric cars are an unimportant "niche" that doesn't even make any money for the leading company with cars that are very expensive!

This is the kind of thinking that drove Kodak. Early digital cameras had lots of limitations. They were expensive. They didn't have the resolution of film. Very few people wanted them. And the early manufacturers didn't make any money. For Kodak it was obvious that the company needed to remain focused on its core film and camera business, as digital cameras just weren't important.

Of course we know how that story ended. With Kodak filing bankruptcy in 2012. Because what initially looked like a limited market, with problematic products, eventually shifted. The products became better, and other technologies came along making digital cameras a better fit for user needs.

Tesla, smartly, has not tried to make a gasoline car into an electric car – like, say, the Ford Focus Electric. Instead Tesla set out to make the best car possible. And the company used electricity as the power source. By starting early, and putting its resources into the best possible solution, in 2013 Consumer Reports gave the Model S 99 out of 100 points. That made it not just the highest rated electric car, but the highest rated car EVER REVIEWED!

As the big car companies point out limits to electric vehicles, Tesla keeps making them better and addresses market limitations. Worries about how far an owner can drive on a charge creates "range anxiety." To cope with this Tesla not only works on battery technology, but has launched a program to build charging stations across the USA and Canada. Initially focused on the Los-Angeles to San Franciso and Boston to Washington corridors, Tesla is opening supercharger stations so owners are never less than 200 miles from a 30 minute fast charge. And for those who can't wait Tesla is creating a 90 second battery swap program to put drivers back on the road quickly.

This is how the classic "Innovator's Dilemma" develops. The existing competitors focus on their core business, even though big sales produce ever declining profits. An upstart takes on a small segment, which the big companies don't care about. The big companies say the upstart products are pretty much irrelevant, and the sales are immaterial. The big companies choose to keep focusing on defending and extending their "core" even as competition drives down results and customer satisfaction wanes.

Meanwhile, the upstart keeps plugging away at solving problems. Each month, quarter and year the new entrant learns how to make its products better. It learns from the initial customers – who were easy for big companies to deride as oddballs – and identifies early limits to market growth. It then invests in product improvements, and market enhancements, which enlarge the market.

Eventually these improvements lead to a market shift. Customers move from one solution to the other. Not gradually, but instead quite quickly. In what's called a "punctuated equilibrium" demand for one solution tapers off quickly, killing many competitors, while the new market suppliers flourish. The "old guard" companies are simply too late, lack product knowledge and market savvy, and cannot catch up.

- The integrated steel companies were killed by upstart mini-mill manufacturers like Nucor Steel.

- Healthier snacks and baked goods killed the market for Hostess Twinkies and Wonder Bread.

- Minolta and Canon digital cameras destroyed sales of Kodak film – even though Kodak created the technology and licensed it to them.

- Cell phones are destroying demand for land line phones.

- Digital movie downloads from Netflix killed the DVD business and Blockbuster Video.

- CraigsList plus Google stole the ad revenue from newspapers and magazines.

- Amazon killed bookstore profits, and Borders, and now has its sites set on WalMart.

- IBM mainframes and DEC mini-computers were made obsolete by PCs from companies like Dell.

- And now Android and iOS mobile devices are killing the market for PCs.

There is no doubt that GM, Ford, Nissan, et. al., with their vast resources and well educated leadership, could do what Tesla is doing. Probably better. All they need is to set up white space companies (like GM did once with Saturn to compete with small Japanese cars) that have resources and free reign to be disruptive and aggressively grow the emerging new marketplace. But they won't, because they are busy focusing on their core business, trying to defend & extend it as long as possible. Even though returns are highly problematic.

Tesla is a very, very good car. That's why it has a long backlog. And it is innovating the market for charging stations. Tesla leadership, with Elon Musk thought to be the next Steve Jobs by some, is demonstrating it can listen to customers and create solutions that meet their needs, wants and wishes. By focusing on developing the new marketplace Tesla has taken the lead in the new marketplace. And smart investors can see that long-term the odds are better to buy into the lead horse before the market shifts, rather than ride the old horse until it drops.

by Adam Hartung | Jul 11, 2012 | Current Affairs, Defend & Extend, Disruptions, Innovation, Leadership, Lock-in

The news is not good for U.S. auto companies. Automakers are resorting to fairly radical promotional programs to spur sales. Chevrolet is offering a 60-day money back guarantee. And Chrysler is offering 90 day delayed financing. Incentives designed to make you want to buy a car, when you really don't want to buy a car. At least, not the cars they are selling.

On the other hand, the barely known, small and far from mainstream Tesla motors gave one of its new Model S cars to Wall Street Journal reviewer Dan Neil, and he gave it a glowing testimonial. He went so far as to compare this 4-door all electric sedan's performance with the Lamborghini and Ford GT supercars. And its design with the Jaguar. And he spent several paragraphs on its comfort, quiet, seating and storage – much more aligned with a Mercedes S series.

There are no manufacturer incentives currently offered on the Tesla Model S.

What's so different about Tesla and GM or Ford? Well, everything. Tesla is a classic case of a disruptive innovator, and GM/Ford are classic examples of old-guard competitors locked into sustaining innovation. While the former is changing the market – like, say Amazon is doing in retail – the latter keeps laughing at them – like, say Wal-Mart, Best Buy, Circuit City and Barnes & Noble have been laughing at Amazon.

Tesla did not set out to be a car company, making a slightly better car. Or a cheaper car. Or an alternative car. Instead it set out to make a superior car.

Its initial approach was a car that offered remarkable 0-60 speed performance, top end speed around 150mph and superior handling. Additionally it looked great in a 2-door European style roadster package. Simply, a wildly better sports car. Oh, and to make this happen they chose to make it all-electric, as well.

It was easy for Detroit automakers to scoff at this effort – and they did. In 2009, while Detroit was reeling and cutting costs – as GM killed off Pontiac, Hummer, Saab and Saturn – the famous Bob Lutz of GM laughed at Tesla and said it really wasn't a car company. Tesla would never really matter because as it grew up it would never compete effectively. According to Mr. Lutz, nobody really wanted an electric car, because it didn't go far enough, it cost too much and the speed/range trade-off made them impractical. Especially at the price Tesla was selling them.

Meanwhile, in 2009 Tesla sold 100% of its production. And opened its second dealership. As manufacturing plants, and dealerships, for the big brands were being closed around the world.

Like all disruptive innovators, Tesla did not make a car for the "mass market." Tesla made a great car, that used a different technology, and met different needs. It was designed for people who wanted a great looking roadster, that handled really well, had really good fuel economy and was quiet. All conditions the electric Tesla met in spades. It wasn't for everyone, but it wasn't designed to be. It was meant to demonstrate a really good car could be made without the traditional trade-offs people like Mr. Lutz said were impossible to overcome.

Now Tesla has a car that is much more aligned with what most people buy. A sedan. But it's nothing like any gasoline (or diesel) powered sedan you could buy. It is much faster, it handles much better, is much roomier, is far quieter, offers an interface more like your tablet and is network connected. It has a range of distance options, from 160 to 300 miles, depending up on buyer preferences and affordability. In short, it is nothing like anything from any traditional car maker – in USA, Japan or Korea.

Again, it is easy for GM to scoff. After all, at $97,000 (for the top-end model) it is a lot more expensive than a gasoline powered Malibu. Or Ford Taurus.

But, it's a fraction of the price of a supercar Ferrari – or even a Porsche Panamera, Mercedes S550, Audi A8, BMW 7 Series, or Jaguar XF or XJ - which are the cars most closely matching size, roominess and performance.

And, it's only about twice as expensive as a loaded Chevy Volt – but with a LOT more advantages. The Model S starts at just over $57,000, which isn't that much more expensive than a $40,000 Volt.

In short, Tesla is demonstrating it CAN change the game in automobiles. While not everybody is ready to spend $100k on a car, and not everyone wants an electric car, Tesla is showing that it can meet unmet needs, emerging needs and expand into more traditional markets with a superior solution for those looking for a new solution. The way, say, Apple did in smartphones compared to RIM.

Why didn't, and can't, GM or Ford do this?

Simply put, they aren't even trying. They are so locked-in to their traditional ideas about what a car should be that they reject the very premise of Tesla. Their assumptions keep them from really trying to do what Tesla has done – and will keep improving – while they keep trying to make the kind of cars, according to all the old specs, they have always done.

Rather than build an electric car, traditionalists denounce the technology. Toyota pioneered the idea of extending a gas car into electric with hybrids – the Prius – which has both a gasoline and an electric engine.

Hmm, no wonder that's more expensive than a similar sized (and performing) gasoline (or diesel) car. And, like most "hybrid" ideas it ends up being a compromise on all accounts. It isn't fast, it doesn't handle particularly well, it isn't all that stylish, or roomy. And there's a debate as to whether the hybrid even recovers its price premium in less than, say, 4 years. And that is all dependent upon gasoline prices.

Ford's approach was so clearly to defend and extend its traditional business that its hybrid line didn't even have its own name! Ford took the existing cars, and reformatted them as hybrids, with the Focus Hybrid, Escape Hybrid and Fusion Hybrid. How is any customer supposed to be excited about a new concept when it is clearly displayed as a trade-off; "gasoline or hybrid, you choose." Hard to have faith in that as a technological leap forward.

And GM gave the market Volt. Although billed as an electric car, it still has a gasoline engine. And again, it has all the traditional trade-offs. High initial price, poor 0-60 performance, poor high-end speed performance, doesn't handle all that well, isn't very stylish and isn't too roomy. The car Tesla-hating Bob Lutz put his personal stamp on. It does achieve high mpg – compared to a gasoline car – if that is your one and only criteria.

Investors are starting to "get it."

There was lots of excitement about auto stocks as 2010 ended. People thought the recession was ending, and auto sales were improving. GM went public at $34/share and rose to about $39. Ford, which cratered to $6/share in July, 2010 tripled to $19 as 2011 started.

But since then, investor enthusiasm has clearly dropped, realizing things haven't changed much in Detroit – if at all. GM and Ford are both down about 50% – roughly $20/share for GM and $9.50/share for Ford.

Meanwhile, in July of 2010 Tesla was about $16/share and has slowly doubled to about $31.50. Why? Because it isn't trying to be Ford, or GM, Toyota, Honda or any other car company. It is emerging as a disruptive alternative that could change customer perspective on what they should expect from their personal transportation.

Like Apple changed perspectives on cell phones. And Amazon did about retail shopping.

Tesla set out to make a better car. It is electric, because the company believes that's how to make a better car. And it is changing the metrics people use when evaluating cars.

Meanwhile, it is practically being unchallenged as the existing competitors – all of which are multiples bigger in revenue, employees, dealers and market cap of Tesla – keep trying to defend their existing business while seeking a low-cost, simple way to extend their product lines. They largely ignore Tesla's Roadster and Model S because those cars don't fit their historical success formula of how you win in automobile competition.

The exact behavior of disruptors, and sustainers likely to fail, as described in The Innovator's Dilemma (Clayton Christensen, HBS Press.)

Choosing to be ignorant is likely to prove very expensive for the shareholders and employees of the traditional auto companies. Why would anybody would ever buy shares in GM or Ford? One went bankrupt, and the other barely avoided it. Like airlines, neither has any idea of how their industry, or their companies, will create long-term growth, or increase shareholder value. For them innovation is defined today like it was in 1960 – by adding "fins" to the old technology. And fins went out of style in the 1960s – about when the value of these companies peaked.

In a bit of “get them the razor so they will buy the razor blades” CEO Tim Cook’s Apple is increasingly relying upon farming the “installed base” of users to drive additional revenues. Leveraging the “installed base” of users is now THE primary theme for growing Apple sales. And even old-tech guys like Warren Buffett at Berkshire Hathaway love it, as they gobble up Apple shares. As do many analysts, and investors. Apple has paid out over $100B to developers for its services, and generated over $40B in revenues for itself – and with such a large base willing to buy things developers are likely to keep providing more products and working to grow sales.

In a bit of “get them the razor so they will buy the razor blades” CEO Tim Cook’s Apple is increasingly relying upon farming the “installed base” of users to drive additional revenues. Leveraging the “installed base” of users is now THE primary theme for growing Apple sales. And even old-tech guys like Warren Buffett at Berkshire Hathaway love it, as they gobble up Apple shares. As do many analysts, and investors. Apple has paid out over $100B to developers for its services, and generated over $40B in revenues for itself – and with such a large base willing to buy things developers are likely to keep providing more products and working to grow sales.