by Adam Hartung | Nov 5, 2012 | Defend & Extend, In the Swamp, Innovation, Lock-in, Science

Many people equate spending on R&D with investing in innovation. The logic goes that R&D spending is lab spending, and out of labs come innovations. Hence, those that spend a lot on R&D are innovative.

That is faulty logic.

This chart shows R&D spending from the top 20 companies in 2011:

Chart reproduced with permission of Business Insider

Think of your own list of companies that are providing innovations which change your work, or life. Would you include Apple? Amazon? Facebook? Google? Genentech? (Here's the link to Fast Company's 50 most innovative for 2012). Note that none of these companies appear on the list of top R&D spenders.

On the other hand, as you look at the big spender list some things might be apparent:

- Microsoft is #5, spending $9B and nearly 13% of revenue. Yet, for this money in 2012 the world received updates to their aging operating system and office automation software. Both of which failed to register favorable reviews by industry gurus, and are considered far from innovative. And Nokia, which is so floundering some consider it a likely bankruptcy candidate soon, is #7! Despite spending nearly $8B on R&D Nokia is now completely reliant on Microsoft if it is to even survive.

- Autos make up a big part of the group. Toyota, GM, Volkswagen, Honda and Daimler are all on the list, spending a whopping $36B. Yet, even though they give us improvements nobody considers them (especially GM) very innovative. That award would go to little Tesla Motors. Or maybe Tata Motors in India.

- Pharmaceuticals make up the dominant industry. Novartis, Roche, Pfizer, Merck, Johnson & Johnson, Sanofi, GlaxoSmithKline and AstraZeneca are all here – spending a cumulative $54B! Yet, they have all failed to give the world any incredible new drugs, all have profit struggles, and the industry is rife with discussions about weak product pipelines. The future of modern medicine increasingly is shifting to genetic solutions, biologics and more specific alternatives to the historical drug regimes from these aging pharma R&D programs.

Do you see the obvious pattern? Most big R&D spenders are not really seeking innovations. They are spending money on historical programs, following historical patterns and trying to defend and extend the historical business. In other words, they are spending vast sums attempting to sustain (or recapture) historical success. And, as the list shows, largely doing a pretty lousy job of it.

If you were given $10,000 to invest would you select these top 20 R&D spenders – or would you look for other, more innovative companies. From a profitability, rate of return and trend perspective, most of these companies look weak – or downright horrible.

Innovators don't focus on what they spend, but where they spend it.

The companies most known for innovation don't keep spending money year after year on their old business. Instead of digging deeper into what they already know, they invest laterally. They spend money putting the pieces together in new, unique ways. They try to find new solutions to old problems, using new – even fringe – technologies. They try to develop disruptive solutions that actually change the marketplace, rather than trying to make something that already exists better, faster or cheaper.

Lots of people like to think there is "scale" in research. Bigger is better. What's more important, for investors, is that there is "diminishing returns." The more you research an area the more you have to spend to find anything new. The costs keep escalating, as the gains shrink. After investing for a while, continuing to research an area is not a good investment (although it may be very intellectually interesting.)

Most of the companies on this list would be smarter to scrap their existing R&D programs, cut the budget in half (at least,) and then invest it somewhere very different. Instead of looking deeper, they need to look wider – broader. They need to investigate alternative solutions, rather than more of the same. They need to be putting more money on fringe opportunities, and a lot less into the core.

Until they do, few on this list are very good investment bets. You'll do better investing like, and in, the real innovators.

by Adam Hartung | Jul 11, 2012 | Current Affairs, Defend & Extend, Disruptions, Innovation, Leadership, Lock-in

The news is not good for U.S. auto companies. Automakers are resorting to fairly radical promotional programs to spur sales. Chevrolet is offering a 60-day money back guarantee. And Chrysler is offering 90 day delayed financing. Incentives designed to make you want to buy a car, when you really don't want to buy a car. At least, not the cars they are selling.

On the other hand, the barely known, small and far from mainstream Tesla motors gave one of its new Model S cars to Wall Street Journal reviewer Dan Neil, and he gave it a glowing testimonial. He went so far as to compare this 4-door all electric sedan's performance with the Lamborghini and Ford GT supercars. And its design with the Jaguar. And he spent several paragraphs on its comfort, quiet, seating and storage – much more aligned with a Mercedes S series.

There are no manufacturer incentives currently offered on the Tesla Model S.

What's so different about Tesla and GM or Ford? Well, everything. Tesla is a classic case of a disruptive innovator, and GM/Ford are classic examples of old-guard competitors locked into sustaining innovation. While the former is changing the market – like, say Amazon is doing in retail – the latter keeps laughing at them – like, say Wal-Mart, Best Buy, Circuit City and Barnes & Noble have been laughing at Amazon.

Tesla did not set out to be a car company, making a slightly better car. Or a cheaper car. Or an alternative car. Instead it set out to make a superior car.

Its initial approach was a car that offered remarkable 0-60 speed performance, top end speed around 150mph and superior handling. Additionally it looked great in a 2-door European style roadster package. Simply, a wildly better sports car. Oh, and to make this happen they chose to make it all-electric, as well.

It was easy for Detroit automakers to scoff at this effort – and they did. In 2009, while Detroit was reeling and cutting costs – as GM killed off Pontiac, Hummer, Saab and Saturn – the famous Bob Lutz of GM laughed at Tesla and said it really wasn't a car company. Tesla would never really matter because as it grew up it would never compete effectively. According to Mr. Lutz, nobody really wanted an electric car, because it didn't go far enough, it cost too much and the speed/range trade-off made them impractical. Especially at the price Tesla was selling them.

Meanwhile, in 2009 Tesla sold 100% of its production. And opened its second dealership. As manufacturing plants, and dealerships, for the big brands were being closed around the world.

Like all disruptive innovators, Tesla did not make a car for the "mass market." Tesla made a great car, that used a different technology, and met different needs. It was designed for people who wanted a great looking roadster, that handled really well, had really good fuel economy and was quiet. All conditions the electric Tesla met in spades. It wasn't for everyone, but it wasn't designed to be. It was meant to demonstrate a really good car could be made without the traditional trade-offs people like Mr. Lutz said were impossible to overcome.

Now Tesla has a car that is much more aligned with what most people buy. A sedan. But it's nothing like any gasoline (or diesel) powered sedan you could buy. It is much faster, it handles much better, is much roomier, is far quieter, offers an interface more like your tablet and is network connected. It has a range of distance options, from 160 to 300 miles, depending up on buyer preferences and affordability. In short, it is nothing like anything from any traditional car maker – in USA, Japan or Korea.

Again, it is easy for GM to scoff. After all, at $97,000 (for the top-end model) it is a lot more expensive than a gasoline powered Malibu. Or Ford Taurus.

But, it's a fraction of the price of a supercar Ferrari – or even a Porsche Panamera, Mercedes S550, Audi A8, BMW 7 Series, or Jaguar XF or XJ - which are the cars most closely matching size, roominess and performance.

And, it's only about twice as expensive as a loaded Chevy Volt – but with a LOT more advantages. The Model S starts at just over $57,000, which isn't that much more expensive than a $40,000 Volt.

In short, Tesla is demonstrating it CAN change the game in automobiles. While not everybody is ready to spend $100k on a car, and not everyone wants an electric car, Tesla is showing that it can meet unmet needs, emerging needs and expand into more traditional markets with a superior solution for those looking for a new solution. The way, say, Apple did in smartphones compared to RIM.

Why didn't, and can't, GM or Ford do this?

Simply put, they aren't even trying. They are so locked-in to their traditional ideas about what a car should be that they reject the very premise of Tesla. Their assumptions keep them from really trying to do what Tesla has done – and will keep improving – while they keep trying to make the kind of cars, according to all the old specs, they have always done.

Rather than build an electric car, traditionalists denounce the technology. Toyota pioneered the idea of extending a gas car into electric with hybrids – the Prius – which has both a gasoline and an electric engine.

Hmm, no wonder that's more expensive than a similar sized (and performing) gasoline (or diesel) car. And, like most "hybrid" ideas it ends up being a compromise on all accounts. It isn't fast, it doesn't handle particularly well, it isn't all that stylish, or roomy. And there's a debate as to whether the hybrid even recovers its price premium in less than, say, 4 years. And that is all dependent upon gasoline prices.

Ford's approach was so clearly to defend and extend its traditional business that its hybrid line didn't even have its own name! Ford took the existing cars, and reformatted them as hybrids, with the Focus Hybrid, Escape Hybrid and Fusion Hybrid. How is any customer supposed to be excited about a new concept when it is clearly displayed as a trade-off; "gasoline or hybrid, you choose." Hard to have faith in that as a technological leap forward.

And GM gave the market Volt. Although billed as an electric car, it still has a gasoline engine. And again, it has all the traditional trade-offs. High initial price, poor 0-60 performance, poor high-end speed performance, doesn't handle all that well, isn't very stylish and isn't too roomy. The car Tesla-hating Bob Lutz put his personal stamp on. It does achieve high mpg – compared to a gasoline car – if that is your one and only criteria.

Investors are starting to "get it."

There was lots of excitement about auto stocks as 2010 ended. People thought the recession was ending, and auto sales were improving. GM went public at $34/share and rose to about $39. Ford, which cratered to $6/share in July, 2010 tripled to $19 as 2011 started.

But since then, investor enthusiasm has clearly dropped, realizing things haven't changed much in Detroit – if at all. GM and Ford are both down about 50% – roughly $20/share for GM and $9.50/share for Ford.

Meanwhile, in July of 2010 Tesla was about $16/share and has slowly doubled to about $31.50. Why? Because it isn't trying to be Ford, or GM, Toyota, Honda or any other car company. It is emerging as a disruptive alternative that could change customer perspective on what they should expect from their personal transportation.

Like Apple changed perspectives on cell phones. And Amazon did about retail shopping.

Tesla set out to make a better car. It is electric, because the company believes that's how to make a better car. And it is changing the metrics people use when evaluating cars.

Meanwhile, it is practically being unchallenged as the existing competitors – all of which are multiples bigger in revenue, employees, dealers and market cap of Tesla – keep trying to defend their existing business while seeking a low-cost, simple way to extend their product lines. They largely ignore Tesla's Roadster and Model S because those cars don't fit their historical success formula of how you win in automobile competition.

The exact behavior of disruptors, and sustainers likely to fail, as described in The Innovator's Dilemma (Clayton Christensen, HBS Press.)

Choosing to be ignorant is likely to prove very expensive for the shareholders and employees of the traditional auto companies. Why would anybody would ever buy shares in GM or Ford? One went bankrupt, and the other barely avoided it. Like airlines, neither has any idea of how their industry, or their companies, will create long-term growth, or increase shareholder value. For them innovation is defined today like it was in 1960 – by adding "fins" to the old technology. And fins went out of style in the 1960s – about when the value of these companies peaked.

by Adam Hartung | May 25, 2011 | Defend & Extend, Disruptions, In the Swamp, Innovation, Leadership, Lock-in, Openness, Transparency, Web/Tech

Nobody admits to being the innovation killer in a company. But we know they exist. Some these folks “dinosaurs that won’t change.” Others blame “the nay-saying ‘Dr. No’ middle managers.” But when you meet these people, they won’t admit to being innovation killers. They believe, deep in their hearts as well as in their everyday actions, that they are doing the right thing for the business. And that’s because they’ve been chosen, and reinforced, to be the Status Quo Police.

When a company starts it has no norms. But as it succeeds, in order to grow quickly it develops a series of “key success factors” that help it continue growing. In order to grow faster, managers – often in functional roles – are assigned the task of making sure the key success factors are unwaveringly supported. Consistency becomes more important than creativity. And these managers are reinforced, supported, even bonused for their ability to make sure they maintain the status quo. Even if the market has shifted, they don’t shift. They reinforce doing things according to the rules. Just consider:

Quality – Who can argue with the need to have quality? Total Quality Management (TQM,) Continuous Improvement (CI,) and Six Sigma programs all have been glorified by companies hoping to improve product or service quality. If you’re trying to fix a broken product, or process, these work pretty well at helping everyone do their job better.

But these programs live with the mantra “if you can’t measure it, you can’t improve it. Measure everything that’s important.” If you’re innovating, what do you measure? If you’re in a new technology, or manufacturing process, how do you know what you really need to do right? If you’re in a new market, how do you know the key metric for sales success? Is it number of customers called, time with customers, number of customer surveys, recommendation scores, lost sales reports? When you’re trying to do something new, a lot of what you do is respond quickly to instant feedback – whether it’s good feedback or bad.

The key to success isn’t to have critical metrics and measure performance on a graph, but rather to learn from everything you do – and usually to change. Quality people hate this, and can only stand in the way of trying anything new because you don’t know what to measure, or what constitutes a “good” measure. Don’t ever forget that Motorola pretty much invented Six Sigma, and what happened to them in the mobile phone business they pioneered?

Finance. All businesses exist to make money, so who can argue with “show me the numbers. Give me a business plan that shows me how you’re going to make money.” When your’e making an incremental investment to an existing asset or process, this is pretty good advice.

But when you’re innovating, what you don’t know far exceeds what you know. You don’t know how to meet unment needs. You don’t know the market size, the price that people will pay, the first year’s volume (much less year 5,) the direct cost at various volumes, the indirect cost, the cost of marketing to obtain customer attention, the number of sales calls it will take to land a sale, how many solution revisions will be necessary to finally put out the “right” solution, or how sales will ramp up quarterly from nothing. So to create a business plan, you have to guess.

And, oh boy, then it gets ugly. “Where did this number come from? That one? How did you determine that?” It’s not long until the poor business plan writer is ridden out of the meeting on a rail. He has no money to investigate the market, so he can’t obtain any “real” numbers, so the business plan process leads to ongoing investment in the old business, while innovation simply stalls.

Under Akia Morita Sony was a great innovator. But then an MBA skilled in finance took over the top spot. What once was the #1 electronics innovator in the globe has become, well, let’s say they aren’t Apple.

Legal – No company wants to be sued, or take on unnecessary risk. And when you’re selling something, lawyers are pretty good at evaluating the risk in that business, and lowering the risk. While making sure that all the compliance issues are met in order to keep regulators – and other lawyers – out of the business.

But when you’re starting something new, everything looks risky. Customers can sue you for any reason. Suppliers can sue you for not taking product, or using it incorrectly. The technology could fail, or have negative use repercussions. Reguators can question your safety standards, or claims to customers.

From a legal point of view, you’re best to never do anything new. The less new things you do, the less likely you are to make a mistake. So legal’s great at putting up roadblocks to make sure they protect the company from lawsuits, by making sure nothing really new happens. The old General Motors had plenty of lawyers making sure their cars were never too risky – or interesting.

R&D or Product Development – Who doesn’t think it’s good to be a leader in a specific technology? Technology advances have proven invaluable for companies in industries from computers to pharmaceuticals to tractors and even services like on-line banking. Thus R&D and Product Development wants to make sure investments advance the state of the technology upon which the company was built.

But all technologies become obsolete. Or, at least unprofitable. Innovators are frequently on the front end of adopting new technologies. But if they have to obtain buy-in from product development to obtain staffing or money they’ll be at the end of a never-ending line of projects to sustain the existing development trend. You don’t have to look much further than Microsoft to find a company that is great at pouring money into the PC platform (some $9B, 16% of revenue in 2009,) while the market moves faster each year to mobile devices and entertainment (Apple spent 1/8th the Microsoft budget in 2009.)

Sales, Marketing & Distribution – When you want to protect sales to existing customers, or maybe increase them by 5%, then doing more of what you’ve always done is smart. So money is spent to put more salespeople on key accounts, add more money to the advertising budget for the most successful (or most profitable) existing products. There are more rules about using the brand than lighters at a smoker’s convention. And it’s heresy to recommend endangering the distribution channel that has so successfully helped increase sales.

But innovators regularly need to behave differently. They need to sell to different people – Xerox sold to secretaries while printing press manufacturers sold to printers. The “brand” may well represent a bygone era, and be of no value to someone launching a new product; are you eager to buy a Zenith electronic device? Sprucing up the brand, or even launching something new, may well be a requirement for a new solution to be taken seriously.

And often, to be successful, a new solution needs to cut through the old, high-cost distribution system directly to customers if it is to succeed. Pre-Gerstner IBM kept adding key account sales people in hopes of keeping IT departments from switching out of mainframes to PCs. Sears avoided the shift to on-line sales successfully – and revenue keeps dropping in the stores.

Information Technology – To make more money you automate more functions. Computers are wonderful for reducing manpower in many tasks. So IT implements and supports “standard solutions” that are cost effective for the historical business. Likewise, they set up all kinds of user rules – like don’t go to Facebook or web sites from work – to keep people focused on productivity. And to make sure historical data is secure and regulations are met.

But innovators don’t have a solution mapped out, and all that automated functionality is an enormously expensive headache. When being creative, more time is spent looking for something new than trying to work faster, or harder, so access to more external information is required. Since the solution isn’t developed, there’s precious little to worry about keeping secure. Innovators need to use new tools, and have flexibility to discover advantageous ways to use them, that are far beyond the bounds of IT’s comfort zone.

Newspapers are loaded with automated systems to collect and edit news, to enter display ads, and to “Make up” the printed page fast and cheap. They have automated systems for classified advertising sales and billing, and for display ad billing. And systems to manage subscribers. That technology isn’t very helpful now, however, as newspapers go bankrupt. Now the most critical IT skills are pumping news to the internet in real-time, and managing on-line ads distributed to web users that don’t have subscriptions.

Human Resources – Growth pushes companies toward tighter job descriptions with clear standards for “the kinds of people that succeed around here.” When you want to hire people to be productive at an existing job, HR has the procedures to define the role, find the people and hire them at the most efficient cost. And they can develop a systematic compensation plan that treats everyone “fairly” based upon perceived value to the historical business.

But innovators don’t know what kinds of people will be most successful. Often they need folks who think laterally, across lots fo tasks, rather than deeply about something narrow. Often they need people who are from different backgrounds, that are closer to the emerging market than the historical business. And pay has to be related to what these folks can get in the market, not what seems fair through the lens of the historical business. HR is rarely keen to staff up a new business opportunity with a lot of misfits who don’t appreciate their compensation plan – or the rules so carefully created to circumscribe behavior around the old business.

B.Dalton was America’s largest retail book seller when Amazon.com was founded by Jeff Bezos. Jeff knew nothing about books, but he knew the internet. B.Dalton knew about books, and claimed it knew what book buyers wanted. Two years later B.Dalton went bankrupt, and all those book experts became unemployed. Amazon.com now sells a lot more than books, as it ongoingly and rapidly expands its employee skill sets to enter new markets – like publishing and eReaders.

Innovation requires that leaders ATTACK the Status Quo Police. Everything done to efficiently run the old business is irrelevant when it comes to innovation. Functional folks need to be told they can’t force the innovatoirs to conform to old rules, because that’s exactly why the company needs innovation! Only by attacking the old rules, and being willing to allow both diversity and disruption can the business innovate.

Instead of saying “this isn’t how we do things around here” it is critical leaders make sure functional folks are saying “how can I help you innovate?” What was done in the name of “good business” looks backward – not forward. Status Quo cops have to be removed from the scene – kept from stopping innovation dead in its tracks. And if the internal folks can’t be supportive, that means keeping them out of the innovator’s way entirely.

Any company can innovate. Doing so requires recognizing that the Status Quo Police are doing what they were hired to do. Until you take away their clout, attack their role and stop them from forcing conformance to old dictums, the business can’t hope to innovate.

by Adam Hartung | May 3, 2011 | Current Affairs, Defend & Extend, In the Swamp, Leadership, Lock-in, Web/Tech

For the first time in 20 years, Apple’s quarterly profit exceeded Microsoft’s (see BusinessWeek.com “Microsoft’s Net Falls Below Apple As iPad Eats Into Sales.) Thus, on the face of things, the companies should be roughly equally valued. But they aren’t. This week Microsoft’s market capitalization is about $215B, while Apple’s is about $365B – about 70% higher. The difference is, of course, growth – and how a lack of it changes management!

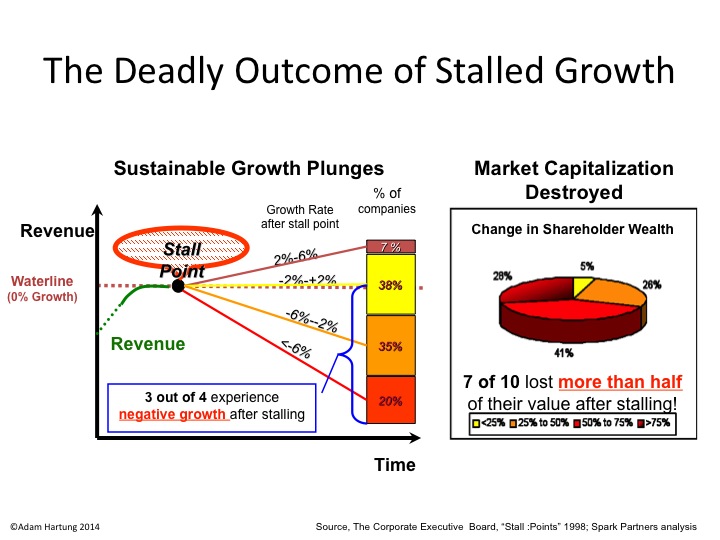

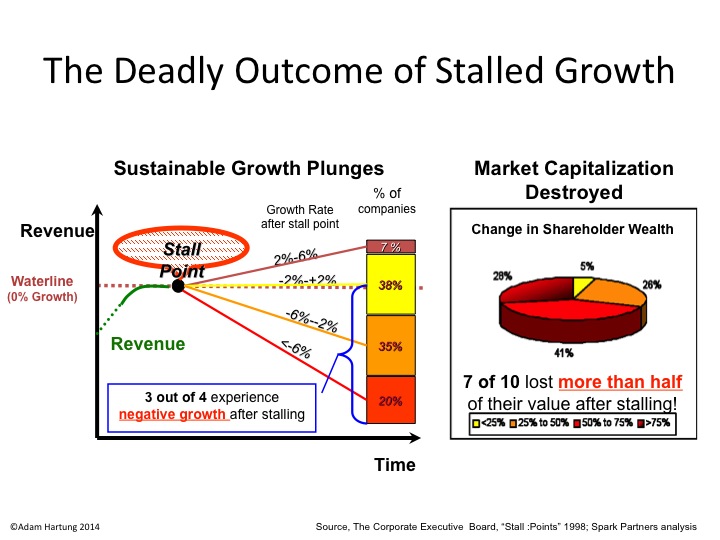

According to the Conference Board, growth stalls are deadly.

When companies hit a growth stall, 93% of the time they are unable to maintain even a 2% growth rate. 75% fall into a no growth, or declining revenue environment, and 70% of them will lose at least half their market capitalization. That’s because the market has shifted, and the business is no longer selling what customers really want.

At Microsoft, we see a company that has been completely unable to deal with the market shift toward smartphones and tablets:

- Consumer PC shipments dropped 8% last quarter

- Netbook sales plunged 40%

Quite simply, when revenues stall earnings become meaningless. Even though Microsoft earnings were up, it wasn’t because they are selling what customers really want to buy. In stalled companies, executives cut costs in sales, marketing, new product development and outsource like crazy in order to prop up earnings. They can outsource many functions. And they go to the reservoir of accounting rules to restate depreciation and expenses, delaying expenses while working to accelerate revenue recognition.

Stalled company management will tout earnings growth, even though revenues are flat or declining. But smart investors know this effort to “manufacture earnings” does not create long-term value. They want “real” earnings created by selling products customers desire; that create incremental, new demand. Success doesn’t come from wringing a few coins out of a declining market – but rather from being in markets where people prefer the new solutions.

Mobile phone sales increased 20% (according to IDC), and Apple achieved 14% market share – #3 – in USA (according to MediaPost.com) last quarter. And in this business, Apple is taking the lion’s share of the profits:

Image provided by BusinessInsider.com

When companies are growing, investors like that they pump earnings (and cash) back into growth opportunities. Investors benefit because their value compounds. In a stalled company investors would be better off if the company paid out all their earnings in dividends – so investors could invest in the growth markets.

But, of course, stalled companies like Microsoft and Research in Motion, don’t do that. Because they spend their cash trying to defend the old business. Trying to fight off the market shift. At Microsoft, money is poured into trying to protect the PC business, even as the trend to new solutions is obvious. Microsoft spent 8 times as much on R&D in 2009 as Apple – and all investors received was updates to the old operating system and office automation products. That generated almost no incremental demand. While revenue is stalling, costs are rising.

At Gurufocus.com the argument is made “Microsoft Q3 2011: Priced for Failure“. Author Alex Morris contends that because Microsoft is unlikely to fail this year, it is underpriced. Actually, all we need to know is that Microsoft is unlikely to grow. Its cost to defend the old business is too high in the face of market shifts, and the money being spent to defend Microsoft will not go to investors – will not yield a positive rate of return – so investors are smart to get out now!

Additionally, Microsoft’s cost to extend its business into other markets where it enters far too late is wildly unprofitable. Take for example search and other on-line products:

Chart source BusinessInsider.com

While much has been made of the ballyhooed relationship between Nokia and Microsoft to help the latter enter the smartphone and tablet businesses, it is really far too late. Customer solutions are now in the market, and the early leaders – Apple and Google Android – are far, far in front. The costs to “catch up” – like in on-line – are impossibly huge. Especially since both Apple and Google are going to keep advancing their solutions and raising the competitive challenge. What we’ll see are more huge losses, bleeding out the remaining cash from Microsoft as its “core” PC business continues declining.

Many analysts will examine a company’s earnings and make the case for a “value play” after growth slows. Only, that’s a mythical bet. When a leader misses a market shift, by investing too long trying to defend its historical business, the late-stage earnings often contain a goodly measure of “adjustments” and other machinations. To the extent earnings do exist, they are wasted away in defensive efforts to pretend the market shift will not make the company obsolete. Late investments to catch the market shift cost far too much, and are impossibly late to catch the leading new market players. The company is well on its way to failure, even if on the surface it looks reasonably healthy. It’s a sucker’s bet to buy these stocks.

Rarely do we see such a stark example as the shift Apple has created, and the defend & extend management that has completely obsessed Microsoft. But it has happened several times. Small printing press manufacturers went bankrupt as customers shifted to xerography, and Xerox waned as customers shifted on to desktop publishing. Kodak declined as customers moved on to film-less digital photography. CALMA and DEC disappeared as CAD/CAM customers shifted to PC-based Autocad. Woolworths was crushed by discount retailers like KMart and WalMart. B.Dalton and other booksellers disappeared in the market shift to Amazon.com. And even mighty GM faltered and went bankrupt after decades of defend behavior, as customers shifted to different products from new competitors.

Not all earnings are equal. A dollar of earnings in a growth company is worth a multiple. Earnings in a declining company are, well, often worthless. Those who see this early get out while they can – before the company collapses.

Update 5/10/11 – Regarding announced Skype acquisition by Microsoft

That Microsoft has apparently agreed to buy Skype does not change the above article. It just proves Microsoft has a lot of cash, and can find places to spend it. It doesn’t mean Microsoft is changing its business approach.

Skype provides PC-to-PC video conferencing. In other words, a product that defends and extends the PC product. Exactly what I predicted Microsoft would do. Spend money on outdated products and efforts to (hopefully) keep people buying PCs.

But smartphones and tablets will soon support video chat from the device; built in. And these devices are already connected to networks – telecom and wifi – when sold. The future for Skype does not look rosy. To the contrary, we can expect Skype to become one of those features we recall, but don’t need, in about 24 to 36 months. Why boot up a PC to do a video chat you can do right from your hand-held, always-on, device?

The Skype acquisition is a predictable Defend & Extend management move. It gives the illusion of excitement and growth, when it’s really “so much ado about nothing.” And now there are $8.5B fewer dollars to pay investors to invest in REAL growth opportunities in growth markets. The ongoing wasting of cash resources in an effort to defend & extend, when the market trends are in another direction.

by Adam Hartung | Dec 17, 2010 | Current Affairs, Defend & Extend, In the Rapids, In the Swamp, Leadership, Web/Tech

Summary:

- Many people think it is OK for large companies to grow slowly

- Many people admire caretaker CEOs

- In dynamic markets, low-growth companies fail

- It is harder to generate $1B of new revenue, than grow a $100B company by $10B

- Large companies have vastly more resources, but they squander them badly

- We allow large company CEOs too much room for mediocrity and failure

- Good CEOs never lose a growth agenda, and everyone wins!

“I may just be your little rent collector Mr. Potter, but that George Bailey is making quite a bit happen in that new development of his. If he keeps going it may just be time for this smart young man to go asking George Bailey for a job.” From “It’s a Wonderful Life“ an employee of the biggest employer in mythical Beford Falls talks about the growth of a smaller competitor.

My last post gathered a lot of reads, and a lot of feedback. Most of it centered on how GE should not be compared to Facebook, largely because of size differences, and therefore how it was ridiculous to compare Jeff Immelt with Mark Zuckerberg. Many readers felt that I overstated the good qualities of Mr. Zuckerberg, while not giving Mr. Immelt enough credit for his skills managing “lower growth businesses” in a “tough economy.” Many viewed Mr. Immelt’s task as incomparably more difficult than that of managing a high growth, smaller tech company from nothing to several billion revenue in a few years. One frequent claim was that it is enough to maintain revenue in a giant company, growth was less important.

Why do so many people give the CEOs of big companies a break? Given that they make huge salaries and bonuses, have fantastic perquesites (private jets, etc.), phenominal benefits and pensions, and receive remarkable payouts whether they succeed or fail I would think we’d have very high standards for these leaders – and be incensed when their performance is sub-par.

Facebook started with almost no resources (as did Twitter and Groupon). Most leaders of start-ups fail. It is remarkably difficult to marshal resources – both enough of them and productively – to grow a company at double digit rates, produce higher revenue, generate cash flow (or loans) and keep employees happy. Growing to a billion dollars revenue from nothing is inexplicably harder than adding $10B to a $100B company. Compared to Facebook, GE has massive resources. Mr. Immelt entered the millenium with huge cash flow, huge revenues, and an army of very smart employees. Mr. Zuckerberg had to come out of the blocks from a standing start and create ALL his company’s momentum, while comparatively Mr. Immelt took on his job riding a bullet out of a gun! GE had huge momentum, a low cost of capital, and enough resources to do anything it wanted.

Yet somehow we should think that we don’t have as high expectations from Mr. Immelt as we do Mr. Zuckerberg? That would seem, at the least, distorted.

In business school I read the story of how American steel manufacturers were eclipsed by the Japanese. Ending WWII America had almost all the steel capacity. Manufacturers raked in the profits. Japanese and German companies that were destroyed had to rebuild, which they progressively did with more efficient assets. By the 1960s American companies were no longer competitive. Were we to believe that having their industrial capacity destroyed somehow was a good thing for the foreign competitors? That if you want to improve your competitiveness (say in autos) you should drop a nuclear bomb on the facilities (some may like that idea – but not many who live in Detroit I dare say.) In reality the American leaders simply refused to invest in new technologies and growth markets, allowing competitors to end-run them. The American leaders were busy acting as caretakers, and bragging about their success, instead of paying attention to market shifts and keeping their companies successful!

Big companies, like GE, are highly advantaged. They not only have brand, and market position, but cash, assets, employees and vendors in position to help them be even more successful! A smart CEO uses those resources to take the company into growth markets where it can grow revenues, and profits, faster than the marketplace. For example Steve Jobs at Apple, and Eric Schmidt at Google have found new markets, revenues and cash flow beyond their original “core” markets. That’s what Mr. Welch did as predecessor to Mr. Immelt. He didn’t so much take advantage of a growth economy as help create it! Unfortunately, far too many large company CEOs squander their resources on low rate of return projects, trying to defend their existing business rather than push forward.

Most big companies over-invest in known markets, or technologies, that have low growth rates, rather than invest in growth markets, or technologies they don’t know as well. Think about how Motorola invented the smart phone technology, but kept investing in traditional cellular phones. Or Sears, the inventor of “at home shopping” with catalogues closed that division to chase real-estate based retail, allowing Amazon to take industry leadership and market growth. Circuit City ended up investing in its approach to retail until it went bankrupt in 2010 – even though it was a darling of “Good to Great.” Or Microsoft, which launched a tablet and a smart phone, under leader Ballmer re-focused on its “core” operating system and office automation markets letting Apple grab the growth markets with R&D investments 1/8th of Microsoft’s. These management decisions are not something we should accept as “natural.” Leaders of big companies have the ability to maintain, even accelerate, growth. Or not.

Why give leaders in big companies a break just because their historical markets have slower growth? Singer’s leadership realized women weren’t going to sew at home much longer, and converted the company into a defense contractor to maintain growth. Netflix converted from a physical product company (DVDs) into a streaming download company in order to remain vital and grow while Blockbuster filed bankruptcy. Apple transformed from a PC company into a multi-media company to create explosive growth generating enough cash to buy Dell outright – although who wants a distributor of yesterday’s technology (remember Circuit City.) Any company can move forward to be anything it wants to be. Excusing low growth due to industry, or economic, weakness merely gives the incumbent a pass. Good CEOs don’t sit in a foxhole waiting to see if they survive, blaming a tough battleground, they develop strategies to change the battle and win, taking on new ground while the competition is making excuses.

GM was the world’s largest auto company when it went broke. So how did size benefit GM? In the 1980s Roger Smith moved GM into aerospace by acquiring Hughes electronics, and IT services by purchasing EDS – two remarkable growth businesses. He “greenfielded” a new approach to auto manufucturing by opening the wildly successful Saturn division. For his foresight, he was widely chastised. But “caretaker” leadership sold off Hughes and EDS, then forced Saturn to “conform” to GM practices gutting the upstart division of its value. Where one leader recognized the need to advance the company, followers drove GM to bankruptcy by selling out of growth businesses to re-invest in “core” but highly unprofitable traditional auto manufacturing and sales. Meanwhile, as the giant failed, much smaller Kia, Tesla and Tata are reshaping the auto industry in ways most likely to make sure GM’s comeback is short-lived.

CEOs of big companies are paid a lot of money. A LOT of money. Much more than Mr. Zuckerberg at Facebook, or the leaders of Groupon and Netflix (for example). So shouldn’t we expect more from them? (Marketwatch.com “Top CEO Bonuses of 2010“) They control vast piles of cash and other resources, shouldn’t we expect them to be aggressively investing those resources in order to keep their companies growing, rather than blaming tax strategies for their unwillingness to invest? (Wall Street Journal “Obama Pushes CEOs on Job Creation“) It’s precisely because they are so large that we should have high expectations of big companies investing in growth – because they can afford to, and need to!

At the end of the day, everyone wins when CEOs push for growth. Investors obtain higher valuation (Apple is worth more than Microsoft, and almost more than 10x larger Exxon!,) employees receive more pay (see Google’s recent 10% across the board pay raise,) employees have more advancement opportunities as well as personal growth, suppliers have the opportunity to earn profits and bring forward new innovation – creating more jobs and their own growth – rather than constantly cutting price. Answering the Economist in “Why Do Firms Exist?” it is to deliver to people what they want. When companies do that, they grow. When they start looking inward, and try being caretakers of historical assets, products and markets then their value declines.

Can Mr. Zuckerberg run GE? Probably. I’d sure rather have him at the helm of GM, Chrysler, Kraft, Sara Lee, Motorola, AT&T or any of a host of other large companies that are going nowhere the caretaker CEOs currently making excuses for their lousy performance. Think what the world would be like if the aggressive leaders in those smaller companies were in such positions? Why, it might just be like having all of American business run the way Steve Jobs, Jeff Bezos and John Chambers have led their big companies. I struggle to see how that would be a bad thing.