by Adam Hartung | May 15, 2016 | In the Swamp, Investing, real estate, Retail

Last week Sears announced sales and earnings. And once again, the news was all bad. The stock closed at a record, all time low. One chart pretty much sums up the story, as investors are now realizing bankruptcy is the most likely outcome.

Chart Source: Yahoo Finance 5/13/16

Quick Rundown: In January, 2002 Kmart is headed for bankruptcy. Ed Lampert, CEO of hedge fund ESL, starts buying the bonds. He takes control of the company, makes himself Chairman, and rapidly moves through proceedings. On May 1, 2003, KMart begins trading again. The shares trade for just under $15 (for this column all prices are adjusted for any equity transactions, as reflected in the chart.)

Lampert quickly starts hacking away costs and closing stores. Revenues tumble, but so do costs, and earnings rise. By November, 2004 the stock has risen to $90. Lampert owns 53% of Kmart, and 15% of Sears. Lampert hires a new CEO for Kmart, and quickly announces his intention to buy all of slow growing, financially troubled Sears.

In March, 2005 Sears shareholders approve the deal. The stock trades for $126. Analysts praise the deal, saying Lampert has “the Midas touch” for cutting costs. Pumped by most analysts, and none moreso than Jim Cramer of “Mad Money” fame (Lampert’s former roommate,) in 2 years the stock soars to $178 by April, 2007. So far Lampert has done nothing to create value but relentlessly cut costs via massive layoffs, big inventory reductions, delayed payments to suppliers and store closures.

Homebuilding falls off a cliff as real estate values tumble, and the Great Recession begins. Retailers are creamed by investors, and appliance sales dependent Sears crashes to $33.76 in 18 months. On hopes that a recovering economy will raise all boats, the stock recovers over the next 18 months to $113 by April, 2010. But sales per store keep declining, even as the number of stores shrinks. Revenues fall faster than costs, and the stock falls to $43.73 by January, 2013 when Lampert appoints himself CEO. In just under 2.5 years with Lampert as CEO and Chairman the company’s sales keep falling, more stores are closed or sold, and the stock finds an all-time low of $11.13 – 25% lower than when Lampert took KMart public almost exactly 13 years ago – and 94% off its highs.

What happened?

Sears became a retailing juggernaut via innovation. When general stores were small and often far between, and stocking inventory was precious, Sears invented mail order catalogues. Over time almost every home in America was receiving 1, or several, catalogues every year. They were a major source of purchases, especially by people living in non-urban communities. Then Sears realized it could open massive stores to sell all those things in its catalogue, and the company pioneered very large, well stocked stores where customers could buy everything from clothes to tools to appliances to guns. As malls came along, Sears was again a pioneer “anchoring” many malls and obtaining lower cost space due to the company’s ability to draw in customers for other retailers.

To help customers buy more Sears created customer installment loans. If a young couple couldn’t afford a stove for their new home they could buy it on terms, paying $10 or $15 a month, long before credit cards existed. The more people bought on their revolving credit line, and the more they paid Sears, the more Sears increased their credit limit. Sears was the “go to” place for cash strapped consumers. (Eventually, this became what we now call the Discover card.)

In 1930 Sears expanded the Allstate tire line to include selling auto insurance – and consumers could not only maintain their car at Sears they could insure it as well. As its customers grew older and more wealthy, many needed help with financia advice so in 1981 Sears bought Dean Witter and made it possible for customers to figure out a retirement plan while waiting for their tires to be replaced and their car insurance to update.

To put it mildly, Sears was the most innovative retailer of all time. Until the internet came along. Focused on its big stores, and its breadth of products and services, Sears kept trying to sell more stuff through those stores, and to those same customers. Internet retailing seemed insignificantly small, and unappealing. Heck, leadership had discontinued the famous catalogues in 1993 to stop store cannibalization and push people into locations where the company could promote more products and services. Focusing on its core customers shopping in its core retail locations, Sears leadership simply ignored upstarts like Amazon.com and figured its old success formula would last forever.

But they were wrong. The traditional Sears market was niched up across big box retailers like Best Buy, clothiers like Kohls, tool stores like Home Depot, parts retailers like AutoZone, and soft goods stores like Bed, Bath & Beyond. The original need for “one stop shopping” had been overtaken by specialty retailers with wider selection, and often better pricing. And customers now had credit cards that worked in all stores. Meanwhile, for those who wanted to shop for many things from home the internet had taken over where the catalogue once began. Leaving Sears’ market “hollowed out.” While KMart was simply overwhelmed by the vast expansion of WalMart.

What should Lampert have done?

There was no way a cost cutting strategy would save KMart or Sears. All the trends were going against the company. Sears was destined to keep losing customers, and sales, unless it moved onto trends. Lampert needed to innovate. He needed to rapidly adopt the trends. Instead, he kept cutting costs. But revenues fell even faster, and the result was huge paper losses and an outpouring of cash.

To gain more insight, take a look at Jeff Bezos. But rather than harp on Amazon.com’s growth, look instead at the leadership he has provided to The Washington Post since acquiring it just over 2 years ago. Mr. Bezos did not try to be a better newspaper operator. He didn’t involve himself in editorial decisions. Nor did he focus on how to drive more subscriptions, or sell more advertising to traditional customers. None of those initiatives had helped any newspaper the last decade, and they wouldn’t help The Washington Post to become a more relevant, viable and profitable company. Newspapers are a dying business, and Bezos could not change that fact.

Mr. Bezos focused on trends, and what was needed to make The Washington Post grow. Media is under change, and that change is being created by technology. Streaming content, live content, user generated content, 24×7 content posting (vs. deadlines,) user response tracking, readers interactivity, social media connectivity, mobile access and mobile content — these are the trends impacting media today. So that was where he had leadership focus. The Washington Post had to transition from a “newspaper” company to a “media and technology company.”

So Mr. Bezos pushed for hiring more engineers – a lot more engineers – to build apps and tools for readers to interact with the company. And the use of modern media tools like headline testing. As a result, in October, 2015 The Washington Post had more unique web visitors than the vaunted New York Times. And its lead is growing. And while other newspapers are cutting staff, or going out of business, the Post is adding writers, editors and engineers. In a declining newspaper market The Washington Post is growing because it is using trends to transform itself into a company readers (and advertisers) value.

CEO Lampert could have chosen to transform Sears Holdings. But he did not. He became a very, very active “hands on” manager. He micro-managed costs, with no sense of important trends in retail. He kept trying to take cash out, when he needed to invest in transformation. He should have sold the real estate very early, sensing that retail was moving on-line. He should have sold outdated brands under intense competitive pressure, such as Kenmore, to a segment supplier like Best Buy. He then should have invested that money in technology. Sears should have been a leader in shopping apps, supplier storefronts, and direct-to-customer distribution. Focused entirely on defending Sears’ core, Lampert missed the market shift and destroyed all the value which initially existed in the great retail merger he created.

Impact?

Every company must understand critical trends, and how they will apply to their business. Nobody can hope to succeed by just protecting the core business, as it can be made obsolete very, very quickly. And nobody can hope to change a trend. It is more important than ever that organizations spend far less time focused on what they did, and spend a lot more time thinking about what they need to do next. Planning needs to shift from deep numerical analysis of the past, and a lot more in-depth discussion about technology trends and how they will impact their business in the next 1, 3 and 5 years.

Sears Holdings was a 13 year ride. Investor hope that Lampert could cut costs enough to make Sears and KMart profitable again drove the stock very high. But the reality that this strategy was impossible finally drove the value lower than when the journey started. The debacle has ruined 2 companies, thousands of employees’ careers, many shopping mall operators, many suppliers, many communities, and since 2007 thousands of investor’s gains. Four years up, then 9 years down. It happened a lot faster than anyone would have imagined in 2003 or 2004. But it did.

And it could happen to you. Invert your strategic planning time. Spend 80% on trends and scenario planning, and 20% on historical analysis. It might save your business.

by Adam Hartung | Aug 2, 2015 | Current Affairs, In the Rapids, In the Swamp, Leadership, Web/Tech

eBay was once a game changer. When the internet was very young, and few businesses provided ecommerce, eBay was a pioneer. From humble beginnings selling Pez dispensers, eBay grew into a powerhouse. Things we used to sell via garage sale we could now list on eBay. Small businesses could create stores on eBay to sell goods to customers they otherwise would never reach. And collectors as well as designers suddenly discovered all kinds of products they formerly could not find. eBay sales exploded, as traditional retail started it slide downward.

To augment growth eBay realized those selling needed a simple way to collect money from people who lacked a credit card. Many customers simply had no card, or didn’t trust giving out the information across the web. So eBay bought fledgling PayPal for $1.5B in 2002, in order to grease the wheels for faster ecommerce growth. And it worked marvelously.

But times have surely changed. Now eBay and Paypal have roughly the same revenue. About $8B/year each. eBay has run into stiff competition, as CraigsList has grown to take over the “garage sale” and small local business ecommerce. Simultaneously, powerhouse Amazon has developed its storefront business to a level of sophistication, and ease of use, that makes it viable for businesses from smallest to largest to sell products on-line. And far more companies have learned they can go it alone with internet sales, using search engine optimization (SEO) techniques as well as social media to drive traffic directly to their stores, bypassing storefronts entirely.

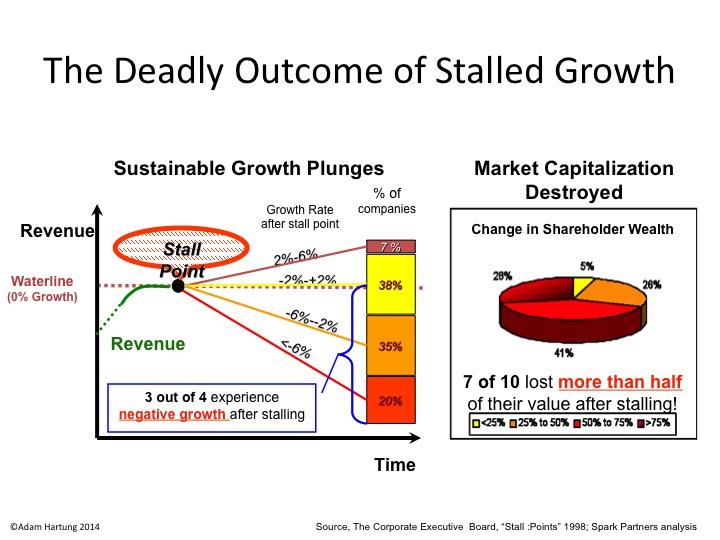

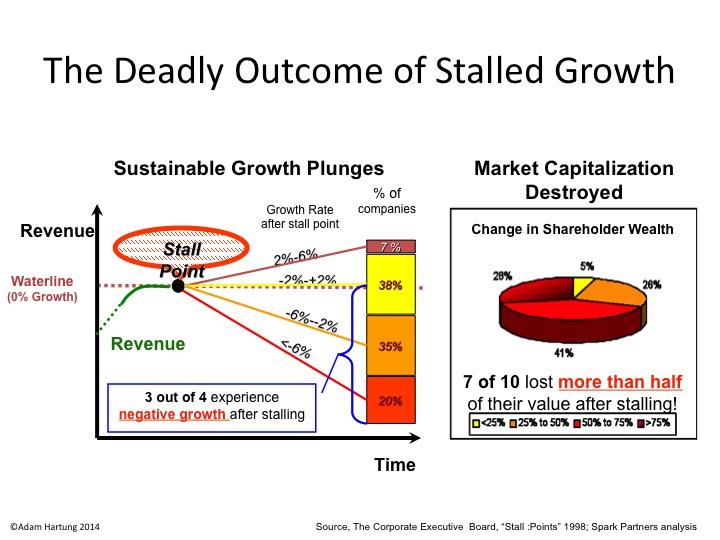

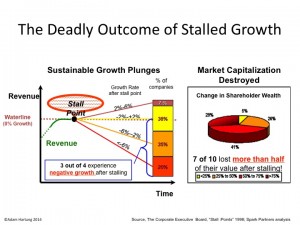

eBay was a game changer, but now is stuck in practices that have become far less relevant. The result has been 2 consecutive quarters of declining revenue. By definition that puts eBay in a growth stall, and fewer than 7% of companies ever recover from a growth stall to consistently increase revenue by a mere 2%/year. Why not? Because once in a growth stall the company has already missed the market shift, and competition is taking customers quickly in new directions. The old leader, like eBay, keeps setting aggressive targets for its business, and tells everyone it will find new customers in remote geographies or vertical markets. But it almost never happens – because the market shift is making their offering obsolete.

eBay was a game changer, but now is stuck in practices that have become far less relevant. The result has been 2 consecutive quarters of declining revenue. By definition that puts eBay in a growth stall, and fewer than 7% of companies ever recover from a growth stall to consistently increase revenue by a mere 2%/year. Why not? Because once in a growth stall the company has already missed the market shift, and competition is taking customers quickly in new directions. The old leader, like eBay, keeps setting aggressive targets for its business, and tells everyone it will find new customers in remote geographies or vertical markets. But it almost never happens – because the market shift is making their offering obsolete.

On the other hand, Paypal has blossomed into a game changer in its own right. Not only does it support cash and credit card transactions for the growing legions of on-line shoppers, but it is providing full payment systems for providers like Uber and AirBnB. It’s tools support enterprise transactions in all currencies, including emerging bitcoin, and even provides international financial transactions as well as working capital for businesses.

Paypal is increasingly becoming a threat to traditional banks. Today most folks use a bank for depositing a pay check, and making payments. There are loans, but frequently that is shopped around irrespective of where you bank. Much like your credit cards, which most people acquire for their benefits rather than a relationship with the issuing bank. If customers increasingly make payments via Paypal, and borrow money via operations like Quicken Loans (a division of Intuit,) why do you need a bank? Discover Services, which now does offer cash deposits and loans on top of credit card services, has found that it can grow substantially by displacing traditional banks.

Paypal is today at the forefront of digital payments processing. It is a fast growing market, which will displace many traditional banks. And emerging competitors like Apple Pay and Google Wallet will surely change the market further – while aiding its growth. How it will shake out is unclear. But it is clear that Paypal is growing its revenue at 60% or greater since 2012, and at over 100%/quarter the last 2 quarters.

Paypal is now valued at about $47B. That is roughly the same as the #5 bank in America (according to assets) Bank of New York Mellon, and number 8 massive credit card issuer Capital One, as well as #9 PNC Bank – and over 50% higher valuation than #10 State Street. It is also about 50% higher than Intuit and Discover. Based on its current market leadership and position as likely game changer for the banking sector, Paypall is selling for about 8 times revenue. If its revenue continues to grow at 100%/quarter, however, revenues will reach over $38B in a year making the Price/Revenue multiple of today only 1.25.

Meanwhile, eBay is valued at about $34B. Given that all which is left in eBay is an outdated on-line ecommerce conglomerator, stuck in a growth stall, that valuation is far harder to justify. It is selling at about 4.25x revenue. But if revenues continue declining, as they have for 2 consecutive quarters, this multiple will expand. And values will be harder and harder to justify as investors rely on hope of a turnaround.

eBay was a game changer. But leadership became complacent, and now it is very likely overvalued. Just as Yahoo became when its value relied on its holdings of Alibaba rather as its organic business shrank. Meanwhile Paypal is the leader in a rapidly growing market that is likely to change the face of not just how we pay, but how we do personal and business finance. There is no doubt which is more valuable today, and likely to be in the future.

by Adam Hartung | Apr 15, 2015 | Defend & Extend, In the Swamp, Leadership

The money is not going into developing any new markets or new products. It is not being used to finance growth of GE at all. Rather, Mr. Immelt will immediately begin a massive $50B stock buyback program in order to prop up the stock price for investors.

When Mr. Immelt took the job of CEO GE sold for about $40/share. Last week it was trading for about $25/share. A decline of 37.5%. During that same time period the Dow Jones Industrial Average, of which GE is the oldest component, rose from 9,600 to 17,900. An increase of 86.5%. This has been a very, very long period of quite unsatisfactory performance for Mr. Immelt.

When Mr. Immelt took the job of CEO GE sold for about $40/share. Last week it was trading for about $25/share. A decline of 37.5%. During that same time period the Dow Jones Industrial Average, of which GE is the oldest component, rose from 9,600 to 17,900. An increase of 86.5%. This has been a very, very long period of quite unsatisfactory performance for Mr. Immelt.

Prior to Mr. Immelt GE was headed by Jack Welch. During his tenure at the top of GE the company created more wealth for its investors than any company ever in the recorded history of U.S. publicly traded companies. GE’s value increased 40-fold (4000%) from 1981 to 2001. He expanded GE into new businesses, often far removed from its industrial manufacturing roots, as market shifts created new opportunities for growing revenues and profits. From what was mostly a diversified manufacturing company Mr. Welch lead GE into real estate as those assets increased in value, then media as advertising revenues skyrocketed and finally financial services as deregulation opened the market for the greatest returns in banking history.

Jack Welch was the Steve Jobs of his era. Because he had the foresight to push GE into new markets, create new products and grow the company. Growth that was so substantial it kept GE constantly in the news, and investors thrilled.

But Mr. Immelt – not so much. During his tenure GE has not developed any new markets. He has not led the company into any growth areas. As the world of portable technology has exploded, making a fortune for Apple and Google investors, GE missed the entire movement into the Internet of Things. Rather than develop new products building on new technologies in wifi, portability, mobility and social Mr. Immelt’s GE sold the appliance division to Electrolux and spent the $3.3B on stock buybacks.

Mr. Immelt’s tenure has been lacked by a complete lack of vision. Rather than looking ahead and preparing for market shifts, Immelt’s GE has reacted to market changes – usually for the poorer. Unprepared for things going off-kilter in financial services, the company was rocked by the financial meltdown and was only saved by an infusion from Berkshire Hathaway. Now it is exiting the business which generates nearly half its profits, claiming it doesn’t want to deal with regulations, rather than figuring out how to make it a more successful enterprise. After accumulating massive real estate holdings, instead of selling them at the peak in the mid-2000s it is now exiting as fast as possible in a recovering economy – to let the fund managers capture gains from improving real estate.

GE is now repatriating some $36B in foreign profits, on which it will pay $6B in taxes. Investors should realize this is happening at the strongest value of the dollar since Mr. Immelt took office. If GE needed these funds, which have been in offshore currencies such as the Euro, it could have repatriated them anytime in the last 3 years and those funds would have been $50B instead of $36B! To say the timing of this transaction could not have been poorer ….

The only thing into which Mr. Immelt has invested has been GE stock. And even that has been a lousy spend, as the price has gone down rather than up! Smart investors have realized that there is no growth in Immelt’s GE, and they have dumped the stock faster than he could buy it. Mr. Immelt’s Harvard MBA gave him insight to financial engineering, but unfortunately not how to lead and grow a major corporation. After 15 years Immelt will leave GE a much smaller, and as he said in the press release, “simpler” business. Apparently it was too big and complicated for him to run.

In the GE statement Mr. Immelt states “This is a major step in our strategy to focus GE around its competitive advantage.” Sorry Mr. Immelt, but that is not a strategy. Identifying growing markets and technologies to create strong, high profit positions with long-term returns is a strategy. Using vague MBA-esque language to hide what is an obvious effort at salvaging a collapsing stock price for another 2 years has nothing to do with strategy. It is a financial tactic.

The Immelt era is the story of a GE which has reacted to events, rather than lead them. Where Steve Jobs took a broken, floundering company and used vision to guide it to great wealth, and Jack Welch used vision to build one of the world’s most resilient and strong corporations, Jeffrey Immelt and his team were overtaken by events at almost every turn. CEO Immelt took what was perhaps the leading corporation of the last century and will leave it in dire shape, lacking a plan for re-establishing its once great heritage. It is a story of utterly failed leadership.

by Adam Hartung | Feb 16, 2012 | Current Affairs, In the Rapids, Innovation, Leadership

Everyone hears about the growth at Apple. But far too few of us hear about great growth stories of start-up companies in non-tech industries that use today's sales tools to change the game and steal sales leadership from traditional competitors.

Jefferson Financial, which moved its headquarters from New York to Louisville, created dramatic, rapid growth using Twitter and Linked-in to take on industry giants like Schwab and B of A's Merrill Lynch. Readers should take this story to heart, because it shows the kind of success small and medium-sized businesses can have when they break out of traditional thinking and invest in new sales tools while stalwarts remain stuck doing the same old thing with diminishing results.

The Jefferson Financial Story – from Ron Volper, Ph.D

Companies that reduce their sales and marketing budgets in this tough economy—as most have– are doing exactly the wrong thing. While many are trying to cut their way out of the recession, the companies that are thriving in this economy are growing their way out by investing more in sales and marketing. And by capitalizing on new trends, such as social media and technology, to reach out to their customers.

That's what enabled Jefferson National Financial to grow its 2010 $180 million revenues to $280 million in 2011 (a 55% annual increase!) — and capture the dominant market share from much larger companies like Charles Schwab — selling financial products such as variable rate annuities to registered investment advisors and their clients throughout the US.

While most industry competitors cut their sales and customer service teams in the recessionary economy, Jefferson National tripled its sales team from 2010 to 2011. While competitors slashed advertising and marketing, Jefferson National substantially increased its advertising and marketing budget. Sound risky? Read on for the results.

Jefferson National combined hi-tech and hi-touch. For example, it used LinkedIn, Twitter, and YouTube to reach financial advisors (the intermediaries that recommend its products) and their clients (the investors). The company capitalized on a slew of tweets and re-tweets highlighting its relocation to Louisville and the creation of 95 new high paying management jobs. Social excitement induced both the mayor and the governor to attend a celebratory event, and encouraged the governor to designate a day as Jefferson National Day – creating a low cost media following of the company, its products and its success.

Successful viral marketing combined hi-tech social involvement with classic event marketing.

Lacking anything exciting to say, many of Jefferson's competitors reduced their fees (prices) for products and services to maintain revenues. Jefferson National was able to maintain its fees by successfully pitching its story directly to customers on-line, then following up with personal assistance, adding value and promoting a successful investor story. As a result, after only 5 years the company increased its fund offerings from 75 to 350.

Jefferson National leveraged its technology to help financial advisors grow their practices. By hosting financial advisor webinars on how to use Linked-in and other social media to gain referrals from existing clients it created a loyal, growing set of distributors and happy clients.

Additionally, Jefferson National used technology to give financial advisors “an end to end solution” demonstrating to investors on-line, regardless location, the power of tax deferred investment growth, regardless of whether the investor was conservative or aggressive.

The result – the company generated $1 billion in sales since inception and became the market share leader.

According to the Ron Volper Group’s recent analysis of 125 companies (including Jefferson National), 80% of companies that were successful in the 2008-2010 down market (as measured by meeting and exceeding their revenue and earnings goals and capturing market share) recognized that customer buying behavior changed, and altered their sales and marketing approach while their less successful peers kept doing "more of the same."

Unfortunately, too many companies exacerbated failure by cutting advertising and marketing budgets. Today customers demand 8 touches (or contacts) to make a buying decision; whereas prior to 2008 they required only 5 touches. While competition has toughened, customers have simultaneously become MORE demanding! The winners, like Jefferson National, recognized that social media, such as Twitter, Facebook and LinkedIn are immediate and inexpensive ways to attract attention and have followers share their success messages with their networks. Simultaneously they continued to advertise and promote their products in traditional ways, appealing to the widest swath of prospects.

Most companies have not accepted the increased customer demand for increased touch, without higher prices. Most have not modified their marketing and sales approach to take account of changes in customer buying behavior. That’s why this is a perfect time for many small and mid-sized companies to adopt new technologies. These are the "slings" which can allow modern-day business Davids to attack lethargic Goliaths.

Thanks to my colleague Ron Volper for sending along this story. He is a believer that anyone can grow, even in this economy. RON VOLPER, Ph.D., is a leading authority on business development and author of Up Your Sales in a Down Market. As Managing Partner of the Ron Volper Group—Building Better Sales Teams, he has advised 90 Fortune 500 Companies and many mid-sized companies on how to increase sales in tough times and good times; and he has trained over 30,000 salespeople and executives over the past 25 years.

I hope your company can take this story to heart and find ways to incorporate new tools f0r creating growth as market shifts make old strategies less valuable, while creating new opportunities.

by Adam Hartung | May 7, 2009 | Current Affairs, Defend & Extend, In the Swamp, Leadership, Lock-in

Good public policy and good management don't always align. And the banking crisis is a good example. We now hear "Banks must raise $75billion" if they are to be prepared for ongoing write-downs in a struggling economy. This is after all the billions already loaned to keep them afloat the last year.

But the bankers are claiming they will have no problem raising this money as reported in "The rush to raise Capital." "AIG narrows loss" tells how one of the primary contributors to the banking crisis now thinks it will survive. And as a result of this news, "Bank shares largely higher" is another headline reporting how financial stocks surged today post-announcements.

So regulators are feeling better. They won't have to pony up as much money as they might have. And politicians feel better, hoping that the bank crisis is over. And a lot of businesses feel better, hearing that the banks which they've long worked with, and are important to their operations, won't be going under. Generally, this is all considered good news. Especially for those worried about how a soft economy was teetering on the brink of getting even worse.

But the problem is we've just extended the life of some pretty seriously ill patients that will probably continue their bad practices. The bail out probably saved America, and the world, from an economic calamity that would have pushed millions more into unemployment and exacerbated falling asset values. A global "Great Depression II" would have plunged millions of working poor into horrible circumstances, and dramatically damaged the ability of many blue and white collar workers in developed countries to maintain their homes. It would have been a calamity.

But this all happened because of bad practices on the part of most of these financial institutions. They pushed their Success Formulas beyond their capabilities, causing failure. Only because of the bailout were these organizations, and their unhealthy Success Formulas saved. And that sows the seeds of the next problem. In evolution, when your Success Formula fails due to an environomental shift you are wiped out. To be replaced by a stronger, more adaptable and better suited competitor. Thus, evolution allows those who are best suited to thrive while weeding out the less well suited. But, the bailout just kept a set of very weak competitors alive – disallowing a change to stronger and better competitors.

These bailed out banks will continue forward mostly as they behaved in the past. And thus we can expect them to continue to do poorly at servicing "main street" while trying to create risk pass through products that largely create fees rather than economic growth. These banks that led the economic plunge are now repositioned to be ongoing leaders. Which almost assures a continuing weak economy. Newly "saved" from failure, they will Defend & Extend their old Success Formula in the name of "conservative management" when in fact they will perpetuate the behavior that put money into the wrong places and kept money from where it would be most productive.

Free market economists have long discussed how markets have no "brakes". They move to excess before violently reacting. Like a swing that goes all one direction until violently turning the opposite direction. Leaving those at the top and bottom with very upset stomachs and dramatic vertigo. The only way to avert the excessive tops is market intervention – which is what the government bail-out was. It intervened in a process that would have wiped out most of the largest U.S. banks. But, in the wake of that intervention we're left with, well, those same U.S. banks. And mostly the same leaders.

What's needed now are Disruptions inside these banks which will force a change in their Success Formula. This includes leadership changes, like the ousting of Bank of America's Chairman/CEO. But it takes more than changing one man, and more than one bank. It takes Disruption across the industry which will force it to change. Force it to open White Space in which it redefines the Success Formula to meet the needs of a shifted market – which almost pushed them over the edge – before those same shifts do crush the banks and the economy.

And that is now going to be up to the regulators. The poor Secretary of Treasury is already eyeball deep in complaints about his policies and practices. I'm sure he'd love to stand back and avoid more controversy. But, unless the regulatory apparatus now pushes those leading these banks to behave differently, to Disrupt and implement White Space to redefine their value for a changed marketplace, we can expect a protracted period of bickering and very weak returns for these banks. We can expect them to walk a line of ups and downs, but with returns that overall are neutral to declining. And that they will stand in the way of newer competitors who have a better approach to global banking from taking the lead.

So, if you didn't like government intervention to save the banks – you're really going to hate the government intervention intended to change how they operate. If you are glad the government intervened, then you'll find yourself arguing about why the regulators are just doing what they must do in order to get the banks, and the economy, operating the way it needs to in a shifted, information age.