by Adam Hartung | Nov 28, 2014 | Current Affairs, Innovation, Leadership, Web/Tech

Last week I gave 1,000 VHS video tapes to Goodwill Industries. These had been accumulated through 30 years of home movie watching, including tapes purchased for entertaining my 3 children.

It was startling to realize how many of these I had bought, and also surprising to learn they were basically valueless. Not because the content was outdated, because many are still popular titles. But rather because today the content someone wants can be obtained from a streaming download off Amazon or Netflix more conveniently than dealing with these tapes and a mechanical media player.

It isn’t just a shift in technology that made those tapes obsolete. Rather, a major trend has shifted. We don’t really seek to “own” things any more. We’ve become a world of “renters.”

The choice between owning and renting has long been an option. We could rent video tapes, and DVDs. But even though we often did this, most Boomers also ended up buying lots of them. Boomers wanted to own things. Owning was almost always considered better than renting.

Boomers wanted to own their cars, and often more than one. Auto renting was only for business trips. Boomers wanted to own their houses, and often more than one. Why rent a summer home, when, if you could afford it, you could own one. Rent a boat? Wouldn’t it be better to own your own boat (even if you only use it 10 times/year?)

Now we think very, very differently. I haven’t watched a movie on any hard media in several years. When I find time for video entertainment, I simply download what I want, enjoy it and never think about it again. A movie library seems – well – unnecessary.

As a Boomer, there’s all those CDs, cassette tapes (yes, I have them) and even hundreds of vinyl records I own. Yet, I haven’t listened to any of them in years. It’s far easier to simply turn on Pandora or Spotify – or listen to a channel I’ve constructed on YouTube. I really don’t know why I continue to own those old media players, or the media.

Since the big real estate meltdown many people are finding home ownership to be not as good as renting. Why take such a huge risk, paying that mortgage, if you don’t have to?

That this is a trend is even clearer generationally. Younger people really don’t see the benefit of home ownership, not when it means taking on so much additional debt. Home ownership costs are so high that it means giving up a lot of other things. And what’s the benefit? Just to say you own your home?

Where Boomers couldn’t wait to own a car, young people are far less likely. Especially in, or near, urban areas. The cost of auto ownership, including maintenance, insurance and parking, becomes really expensive. Compared with renting a ZipCar for a few hours when you really need a car, ownership seems not only expensive, but a downright hassle.

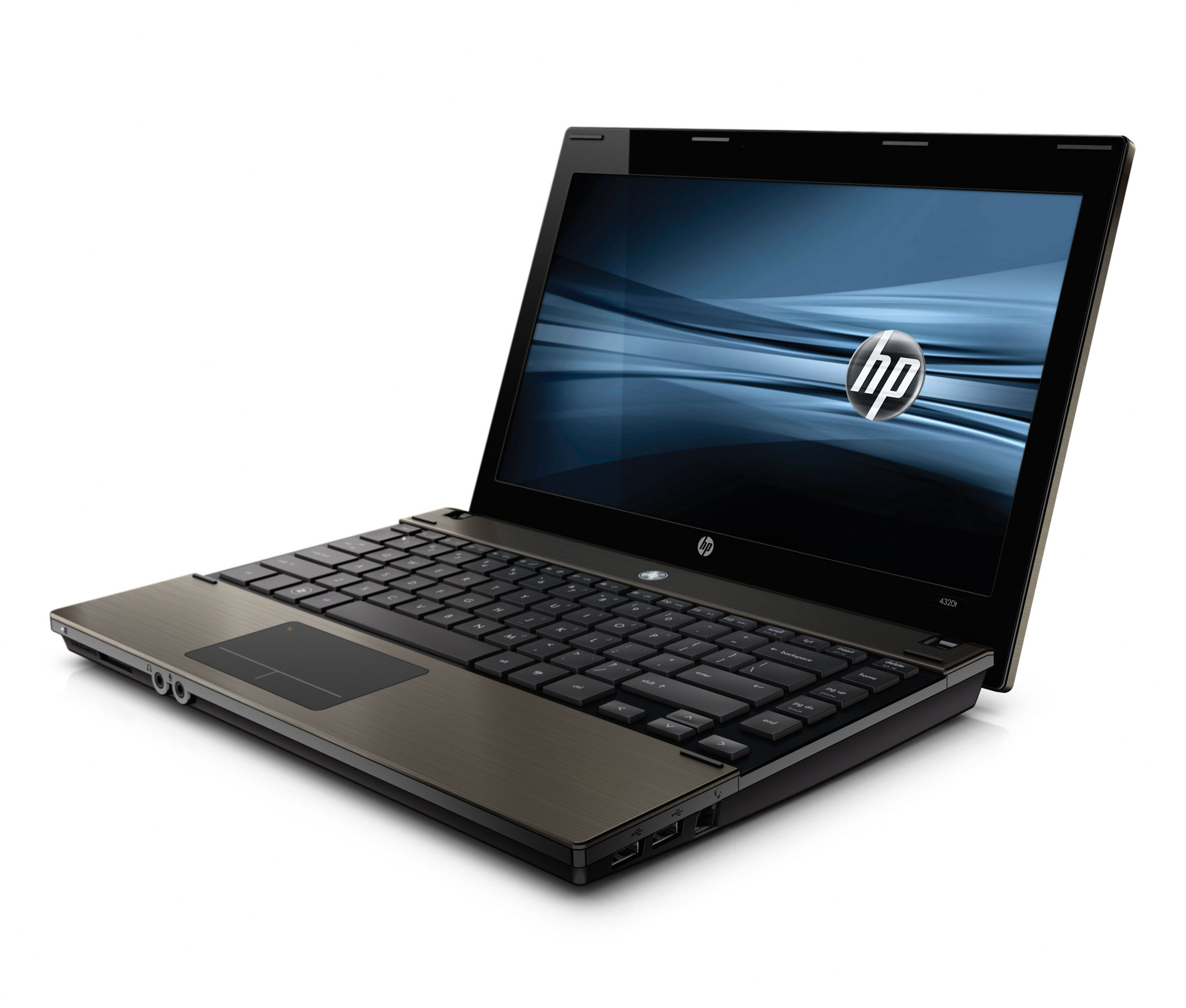

And technology has followed this trend. Once we wanted to own a PC, and on that PC we wanted to own lots of data – including movies, pictures, books – anything that could be digitized. And we wanted to own software applications to capture, view, alter and display that data. The PC was something that fit the Boomer mindset of owning your technology.

But that is rapidly becoming superfluous. With a mobile device you can keep all your data in a cloud. Data you want to access regularly, or data you want to rent. There’s no reason to keep the data on your own hard drive when you can access it 24×7 everywhere with a mobile device.

And the same is true for acting on the data. Software as a service (SaaS) apps allow you to obtain a user license for $10-$20/user, or $.99, or sometimes free. Why spend $200 (or a lot more) for an application when you can accomplish your task by simply downloading a mobile app?

So I no longer want to own a VCR player (or DVD player for that matter) to clutter up my family room. And I no longer want to fill a closet with tapes or cased DVDs. Likewise, I no longer want to carry around a PC with all my data and applications. Instead, a small, easy to use mobile device will allow me to do almost everything I want.

It is this mega trend away from owning, and toward a simpler lifestyle, that will end the once enormous PC industry. When I can do all I really want to do on my connected device – and in fact often do more things because of those hundreds of thousands of apps – why would I accept the size, weight, complexity, failure problems and costs of the PC?

And, why would I want to own something like Microsoft Office? It is a huge set of applications which contain dozens (hundreds?) of functions I never use. Wouldn’t life be much simpler, easier and cheaper if I acquire the rights to use the functionality I need, when I need it?

There was a time I couldn’t imagine living without my media players, and those DVDs, CDs, tapes and records. But today, I’m giving lots of them away – basically for recycling. While we still use PCs for many things today, it is now easy to visualize a future where I use a PC about as often as I now use my DVD player.

In that world, what happens to Microsoft? Dell? Lenovo?

The implications of this are far-reaching for not only our personal lives, and personal technology suppliers, but for corporate IT. Once IT managed mainframes. Then server farms, networks and thousands of PCs. What will a company need an IT department to do if employees use their own mobile devices, across common networks, using apps that cost a few bucks and store files on secure clouds?

If corporate technology is reduced to just operating some “core” large functions like accounting, how big – or strategic – is IT? The “T” (technology) becomes irrelevant as people focus on gathering and analyzing information. But that’s not been the historical training for IT employees.

Further, if Salesforce.com showed us that even big corporations can manage something as critical as their customer information in a SaaS environment on mobile devices, is it not possible to imagine accounting and supply chain being handled the same way? If so, what role will IT have at all?

The trend toward renting rather than owning is monumental. It affects every business. But in an ironic twist of fate, it may dramatically reduce the focus on IT that has been so critical for the Boomer generation.

by Adam Hartung | Nov 19, 2014 | Current Affairs, Leadership

Warren Buffett is the famous head of Berkshire Hathaway. Famous because he has made himself a billionaire several times over, and made his investors excellent returns.

Berkshire Hathaway doesn’t really make anything. Rather, it owns companies that make things, or supply services. So when you buy a share of BRK you are actually buying a piece of the companies it owns, and a piece of the over $116B it invests in equities of other public companies from the cash flow of its owned entities.

Over the last decade the value of a share of BRK has increased 149%. Pretty darn good, considering the DJIA (Dow Jones Industrial Average) has only increased 64%, and the S&P 500 69%, in the same time period. So for long-term investors, putting your money with Mr. Buffett would have done more than twice as good as buying one of these leading indices.

For this reason, many investors recommend looking at what Berkshire Hathaway buys in its equity portfolio, and then buying those same stocks. On the face of it, seems smart. “Invest like Warren Buffet” one might say.

But that would be a bad idea. Berkshire Hathaway’s value has little to do with the publicly traded equities it owns. In fact, those holdings may well be a damper on BRKs valuation.

Of that giant portfolio, 4 equities make up 58% of the total holdings. Let’s look at how those have done the last decade:

- American Express (AXP,) about 10% of the portfolio, is up 83%

- Coke (KO,) about 15% of the portfolio, is up 109%

- IBM (IBM,) about 10% of the portfolio, is up 64%

- Wells Fargo (WFC,) nearly 25% of the portfolio) is up 71%

Note – not one of these stocks is up anywhere near as much as Berkshire Hathaway. There is no mathematical formula which one can use to multiply the gains on these stocks and interpret that into an overall value increase of 149%!

There are several other large, well known companies in the Berkshire Hathaway portfolio which have large (millions of shares being held) but lesser percentage positions:

- ExxonMobil (XOM) up 86%

- General Electric (GE) down <26%>

- Proctor & Gamble (PG) up 61%

- USBancorp (USB) up 40%

- USG (USG) down <30%>

- UPS up 24%

- Verizon up 38%

- Walmart up 61%

This is not to say that Berkshire Hathaway has owned all these stocks for 10 years. And, this is not all the portfolio. But it is well known that Mr. Buffett is a long-term investor who eschews short-term trading. And, these are at least randomly representative of the portfolio holdings. So by buying and selling shares at different times, and using various trading strategies, BRK’s returns could be somewhat better than the performance of these stocks. But, again, there is no arithmetic which exists that can turn the returns on these common stocks into the 149% gain which Berkshire Hathaway has achieved.

Simply put, Berkshire Hathaway makes money by doing things that no individual investor could ever accomplish. The cash flow is so enormous that Mr. Buffett is able to make deals that are not available to you, me or any other investor with less than $1B (or more likely $10B.)

When the banks looked ready to melt down in 2008 GE was in a world of hurt for money to shore up problems in its GE Capital unit. When GE went out to raise $12B via a common stock sale it turned to Mr. Buffett to lead the investment. And he did, taking a $6B position. For being so gracious, in addition to GE shares Berkshire Hathaway was able to buy $3B in preferred shares with a guaranteed dividend of 10%! Additionally, Mr. Buffett was given warrants allowing him to buy up to $3B of GE shares for a fixed price of $22.25 per share regardless of the price at which GE was trading. These are what are called “sweeteners” in the financial trade. They greatly reduce the risk on the common stock purchase, and simultaneously dramatically improve the returns.

These “sweeteners” are not available to us average, ordinary investors. And this is critical to understand. Because if someone thought that Mr. Buffett made all that money by being a good stock picker, that someone would be operating on the wrong assumption. Mr. Buffett is a very good deal maker who gets a lot more when making his investments than we get. He can do that because he can move so much money, so quickly. Faster even than any large bank.

Take, for example, the recent deal for Berkshire Hathaway to acquire the Duracell battery business from P&G. Where most of us (individuals or corporations) would have to fork over the $3B that P&G wanted, Berkshire Hathaway can simply give back P&G shares it has long held. By exchanging those shares for Duracell, Berkshire avoids paying any tax on the stock gains – thus using P&G shares in its portfolio as a currency to buy the battery business with pre-tax dollars rather than the after-tax dollars the rest of us would have to put up. In a nutshell, that saves at least 35%. But, beyond that, the deal also allows P&G to sell Duracell without having to pay tax on the assets from their end of the transaction, saving P&G 35% as well. To make the same deal, any other buyer would have been required to pay a lot more money.

Acquiring Duracell Berkshire gets 100% of another slow-growth but very good cash flow company (like Dairy Queen, Burlington Northern Rail, etc.) and does so at a very favorable price. This deal adds more cash flow to BRK, more assets to BRK, and has nothing to do with whether or not the stocks in its public equity portfolio are outperforming the DJIA or S&P.

This in no way diminishes Berkshire Hathaway, or Mr. Buffett. But it points out that many people have very bad assumptions when it comes to understanding how Mr. Buffett, or rather Berkshire Hathaway, makes money. Berkshire Hathaway is not a mutual fund, and no investor can make a fortune by purchasing common shares in the companies where Mr. Buffett invests.

Berkshire Hathaway is an extremely complicated company, and deep in its core it is an institution that has a tremendous understanding of financial instruments, financial markets, tax laws and risk. It has long owned insurance companies, and its leaders understand actuarial tables as well as how to utilize complex financial instruments and sophisticated tax opportunities to reduce risk, and raise returns, on deals that no one else could make.

By maximizing cash flow from its private holdings the Berkshire Hathaway constantly maintains a very large cash pool (currently some $60B) which it can move very, very quickly to make deals nobody, other than some of the largest private equity pools, could obtain.

The process by which Berkshire Hathaway decides to buy, hold or sell any security is unique to Berkshire Hathaway. The size of its transactions are enormous, and where we as individuals buy shares by the hundreds (the old “round lot,”) Berkshire buys millions. What stocks Berkshire Hathaway chooses to buy, hold or sell has much more to do with the unique situation of Berkshire Hathaway than stock price forecasts for those companies.

It is a myth for an individual investor to think they could invest like Mr. Buffett, and trying to emulate his returns by emulating the Berkshire portfolio is simply unwise.

by Adam Hartung | Nov 12, 2014 | Current Affairs, Defend & Extend, In the Swamp, In the Whirlpool, Leadership

We see it all too often. A successful business seems to lose its way. Somehow, after decades of success, its results soften, then tumble and the company becomes a victim of its competition. We scratch our heads and wonder, “why did that happen?”

Pizza Hut is well on its way to disappearing. Kind of like Pizza Inn, A&W and Howard Johnson’s. And that seems kind of remarkable considering the company at one time defined pizza for most Americans. From a fast growing franchise in the 1960s to a high profile acquisition by PepsiCo in the 1970s, to anchoring the Yum Brands spin out from PepsiCo in 1997, Pizza Hut just finished 8 straight quarters of declining same store sales. Pizza Hut was once a concept as hot as Apple Stores, but now it looks more like Sears. How could this happen?

When Pizza Hut was growing it locked in on its success formula. And one of the biggest Lock-ins was its name. Pizza Hut was a place where you ate pizza, and the buildings all looked the same with that hut-like red roof. At a time when few Americans outside the northeast ate pizza, this Wichita, Kansas founded (and headquartered until the 1990s) company told people what a pizzeria should look like, and what you should eat.

The company was ardent about controlling what franchisees served. No nachos, or other trendy foods, because they didn’t fit the pizza theme. No delivery, because good pizza required you eat it immediately from the oven. Pizza should be thick and hearty, even served in a deep dish so you have plenty of bread and feel really full. Whether anyone in Italy ever a pizza anything like this really did not matter.

And Pizza Hut would help guide customers as to what toppings they wanted — and usually there should be at least 3 – by offering pre-designed pizzas with names like “meat lovers,” “supreme,” “super supreme” or “veggie lover’s” so an uninformed clientele (originally prairie state, then midwestern, then expanding into the southwest and the south) could buy the product without a lot of fuss.

This success formula may sound cliche today, but it worked. And it worked really well for 30 years, then pretty well for another 10-15. But, eventually, doing the same thing over, and over, and over, and over had less appeal. Almost everyone in the country knew what a Pizza Hut was, what the stores looked like and what the product was like. Competitors came along by the dozens with all kinds of variations, and different kinds of service – like being in a mall, or delivering the product. Inevitably this competition led to price wars. To keep customers Pizza Hut had to lower its prices, even offering 2 pizzas for the price of one. Pizza Hut never lost track of its success formula, and never stopped doing what once made it great. But margins eroded, and then sales started declining.

Lots of people don’t care about Pizza Hut any more. They want an alternative. An alternative product, like California Pizza Kitchen or Wolfgang Pucks. Or an alternative to pizza altogether like the new “fast casual” chains such as Chipotle’s, Baja Fresh or Panera. For a whole raft of reasons, people decided that although they once ate Pizza Hut (even ate a LOT of it) they were going to eat something else.

But Pizza Hut was locked in. First, its name. Pizza. Hut. To fulfill the “brand promise” of that name everything about that store is pre-designed. From the outside to the inside tables to the equipment in the kitchen. 6,300 stores that are almost identical. Any change and you have to make 6,300 changes. Adding new product categories means reprinting 126,000 menus, changing 6,300 kitchen layouts, buying 6,300 new ovens, figuring out the service utensils for 6,300 wait staff. That’s lock-in. Making any change is so hard that the incentive is entirely toward improve what you’ve always done rather than doing something new.

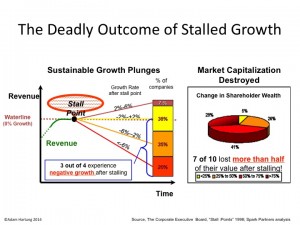

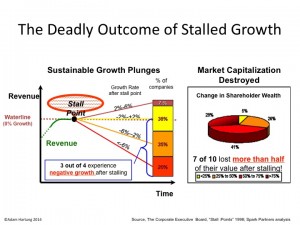

Growth Stalls are Deadly

Eventually, like Pizza Hut, growth stalls. It only takes 2 quarters of declining sales to hit a growth stall, and when that happens less than 7% of businesses will ever again consistently grow at a meager 2%. Growth stalls tell us “hey, the market shifted. What you’re doing isn’t selling any more.”

But most management teams don’t think about a market shift, and instead react by trying to do more of the same. They treat this like its an operational problem. More quality campaigns, more money spent on advertising, more promotions, asking employees to work a little harder, more product for the same (or lower) price – more, better, faster, cheaper. But this doesn’t work, because the problem lies in a market shift away from your “core” that requires an entirely different strategy.

Because management is incented to ignore this shift as long as possible, the company soon becomes irrelevant. Customers know they’ve been going to competitors, and they start to realize it’s been a long time since they bought from that old supplier. They realize their interest in that old company and its products has simply gone away. They don’t pay attention to the ads. And they don’t have any interest in new product announcements. Actually, they find the company irrelevant. Even when the discounts are big, they don’t buy. They do business where they identify with the company and its products, even when those products cost more.

And thus the results start to tumble horribly. Only by now management is so far removed from market trends that it has no idea how to regain relevancy. In Pizza Hut’s case, leadership is undertaking what they’d like to think is a brand overhaul that will change its position in customers’ minds. But, unfortunately, they are doing the ultimate in defend & extend management to try and save the old success formula.

Pizza Hut is introducing a maze of new ways to have its old product, in its old stores. 10 crust choices, 6 sauce choices, 22 of those pre-designed pizza offerings, 5 different liquids you can have dribbled over the pizza, and a rash of exotic new toppings – like banana. So now you can order your pizza 1,000 different ways (actually, more like 10,000.) Oh, and this is being launched with a big increase in traditional advertising. In other words, an insane implementation of what the company has always done; giving customers an American style pizza, in a hut, promoted on TV – even most likely buying what is now considered iconic – a Super Bowl ad.

Yum Brands investors have reasons to be concerned. Pizza Hut is really important to sales and earnings. But its leaders are intent on doing more of the same, even though the market has already shifted. The prognosis does not look good.

by Adam Hartung | Nov 3, 2014 | Current Affairs, In the Rapids, Leadership, Web/Tech

On April 15 Zebra Technologies announced its planned acquisition of Motorola’s Enterprise Device Business. This was remarkable because it represented a major strategic shift for Zebra, and one that would take a massive investment in products and technologies which were wholly new to the company. A gutsy play to make Zebra more relevant in its B-2-B business as interest in its “core” bar code business was declining due to generic competition.

Last week the acquisition was completed. In an example of Jonah swallowing the whale, Zebra added $2.5B to annual revenues on its old base of $1B (2.5x incremental revenue,) an additional 4,500 employees joined its staff of 2,500 and 69 new facilities were added. Gulp.

As CEO Anders Gustafsson told me, “after the deal was agreed to I felt like the dog that caught the car. ”

Fortunately Zebra has a plan, and it is all around growth. Acquisitions led by private equity firms, hedge funds or leveraged buyout partners are usually quick to describe the “synergies” planned for after the acquisition. Synergy is a code word for massive cost cutting (usually meaning large layoffs,) selling off assets (from buildings to product lines and intellectual property rights) and shutting down what the buyers call “marginal” businesses. This always makes the company smaller, weaker and less likely to survive as the new investors focus on pulling out cash and selling the remnants to some large corporation.

There is no growth plan.

But Zebra has publicly announced that after this $3.25B investment they plan only $150M of savings over 2 years. Which means Zebra’s management team intends to grow what they bought, not decimate it. What a novel, or perhaps throwback, idea.

Minimal cost cutting reflects a deal, as CEO Gustafsson told me, “envisioned by management, not by bankers.”

Zebra’s management knew the company was frequently pitching for new work in partnership with Motorola. The two weren’t competitors, but rather two companies working to move their clients forward. But in a disorganized, unplanned way because they were two totally different companies. Zebra’s team recognized that if this became one unit, better planning for clients, the products could work better together, the solutions more directly target customer needs and it would be possible to slingshot forward ahead of competitors to grow revenues.

As CEO since 2007, Anders Gustafsson had pushed a strategy which could grow Zebra, and move the company outside its historical core business of bar code printers and readers. The leadership considered buying Symbol Technology, but wasn’t ready and watched it go to Motorola.

Then Zebra’s team knuckled down on their strategy work. CEO Gustafsson spelled out for me the 3 trends which were identified to build upon:

- Mobility would continue to be a secular growth trend. And business customers needed products with capabilities beyond the generic smart phone. For example, the kind of integrated data entry and printing device used at a remote rental car return. These devices drive business productivity, and customers hunger for such solutions.

- From the days of RFID, where Zebra was an early player, had emerged automatic data capture – which became what now is commonly called “The Internet of Things” – and this trend too had far to extend. By connecting the physical and digital worlds, in markets like retail inventory management, big productivity boosts were possible in formerly moribund work that added cost but little value.

- Cloud-based (SaaS and growth of lightweight apps) ecosystems were going to provide fast growth environments. Client need for capability at the employee’s (or their customer’s) fingertips would grow, and those people (think distributors, value added resellers [VARs]) who build solutions will create apps, accessible via the cloud, to rapidly drive customer productivity.

With this groundwork, the management team developed future scenarios in which it became increasingly clear the value in merging together with Motorola devices to accelerate growth. According to CEO Gustafsson, “it would bring more digital voice to the Zebra physical voice. It would allow for more complete product offerings which would fulfill critical, macro customer trends.”

But, to pull this off required selling the Board of Directors. They are ultimately responsible for company investments, and this was – as described above – a “whopper.”

The CEO’s team spent a lot of time refining the message, to be clear about the benefits of this transaction. Rather than pitching the idea to the Board, they offered it as an opportunity to accelerate strategy implementation. Expecting a wide range of reactions, they were not surprised when some Directors thought this was “phenomenal” while others thought it was “fraught with risk.”

So management agreed to work with the Board to undertake a thorough due diligence process, over many weeks (or months it turned out) to ask all the questions. A key executive, who was a bit skeptical in her own right, took on the role of the “black hat” leader. Her job was to challenge the many ideas offered, and to be a chronic skeptic; to not let the team become enraptured with the idea and thereby sell themselves on success too early, and/or not consider risks thoroughly enough. By persistently undertaking analysis, education led the Board to agree that management’s strategy had merit, and this deal would be a breakout for Zebra.

Next came completing financing. This was a big deal. And the only way to make it happen was for Zebra to take on far more debt than ever in the company’s history. But, the good news was that interest rates are at record low levels, so the cost was manageable.

Zebra’s leadership patiently met with bankers and investors to overview the market strategy, the future scenarios and their plans for the new company. They over and again demonstrated the soundness of their strategy, and the cash flow ability to service the debt. Zebra had been a smaller, stable company. The debt added more dynamism, as did the much greater revenues. The requirement was to decide if the strategy was soundly based on trends, and had a high likelihood of success. Quickly enough, the large shareholders agreed with the path forward, and the financing was fully committed.

Now that the acquisition is complete we will all watch carefully to see if the growth machine this leadership team created brings to market the solutions customers want, so Zebra can generate the revenue and profits investors want. If it does, it will be a big win for not only investors but Zebra’s employees, suppliers and the communities in which Zebra operates.

The obvious question has to be, why didn’t Motorola do this deal? After all, they were the whale. It would have been much easier for people to understand Motorola buying Zebra than the gutsy deal which ultimately happened.

Answering this question requires a lot more thought about history. In 2006 Motorola had launched the Razr phone and was an industry darling. Newly minted CEO Ed Zander started partnering with Google and Apple rather than developing proprietary solutions like Razr. Carl Icahn soon showed up as an activist investor intent on restructuring the company and pulling out more cash. Quickly then-CEO Ed Zander was pushed out the door. New leadership came in, and Motorola’s new product introductions disappeared.

Under pressure from Mr. Icahn, Motorola started shrinking under direction of the new CEO. R&D and product development went through many cuts. New product launches simply were delayed, and died. The cellular phone business began losing money as RIM brought to market Blackberry and stole the enterprise show. Year after year the focus was on how to raise cash at Motorola, not how to grow.

After 4 years, Mr. Icahn was losing money on his position in Motorola. A year later Motorola spun out the phone business, and a year after that leadership paid Mr. Icahn $1.2B in a stock repurchase that saved him from losses. The CEO called this buyout of Icahn the “end of a journey” as Mr. Icahn took the money and ran. How this benefited Motorola is – let’s say unclear.

But left in Icahn’s wake was a culture of cut and shred, rather than invest. After 90 years of invention, from Army 2-way radios to police radios, from AM car radios to home televisions, the inventor analog and digital cell towers and phones, there was no more innovation at Motorola. Motorola had become a company where the leaders, and Board, only thought about how to raise cash – not deploy it effectively within the corporation. There was very little talk about how to create new markets, but plenty about how to retrench to ever smaller “core” markets with no sales growth and declining margins. In September of this year long-term CEO Greg Brown showed no insight for what the company can become, but offered plenty of thoughts on defending tax inversions and took the mantle as apologist for CEOs who use financial machinations to confuse investors.

Investors today should cheer the leadership, in management and on the Board, at Zebra. Rather than thinking small, they thought big. Rather than bragging about their past, they figured out what future they could create. Rather than looking at their limits, they looked at the possibilities. Rather than giving up in the face of objections, they studied the challenges until they had answers. Rather than remaining stuck in their old status quo, they found the courage to become something new.

Bravo.

by Adam Hartung | Oct 28, 2014 | Current Affairs, Defend & Extend, Food and Drink, In the Swamp, Leadership, Lock-in, Television

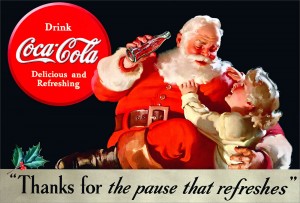

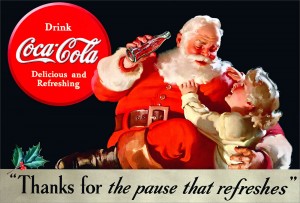

I’m a “Boomer,” and my generation could have been called the Coke generation. Our parents started every day with a cup of coffee, and they drank either coffee or water during the day. Most meals were accompanied by either water, or iced tea.

But our generation loved Coca-Cola. Most of our parents limited our consumption, much to our frustration. Some parents practically refused to let the stuff in the house. In progressive homes as children we were usually only allowed one, or at most two, bottles per day. We chafed at the controls, and when we left home we started drinking the sweet cola as often as we could.

It didn’t take long before we supplanted our parent’s morning coffee with a bottle of Coke (or Diet Coke in more modern times.) We seemingly could not get enough of the product, as bottle size soared from 8 ounces to 12 to 16 and then quarts and eventually 2 liters! Portion control was out the window as we created demand that seemed limitless.

Meanwhile, Americans exported our #1 drink around the world. From 1970 onward Coke was THE iconic American brand. We saw ads of people drinking Coke in every imaginable country. International growth seemed boundless as people from China to India started consuming the irresistible brown beverage.

My how things change. Last week Coke announced third quarter earnings, and they were down 14%. The CEO admitted he was struggling to find growth for the company as soda sales were flat. U.S. sales of carbonated beverages have been declining for a decade, and Coke has not developed a successful new product line – or market – to replace those declines.

Coke is a victim of changing customer preferences. Once a company that helped define those preferences, and built the #1 brand globally, Coke’s leadership shifted from understanding customers and trends in order to build on those trends towards defending & extending sales of its historical product. Instead of innovating, leadership relied on promotion and tactics which had helped the brand grow 30 years ago. They kept to their old success formula as trends shifted the market into new directions.

Coke began losing its relevancy. Trends moved in a new direction. Healthfulness led customers to decide they wanted a less calorie rich, nutritionally starved drink. And concerns grew over “artificial” products, such as sweeteners, leading customers away from even low calorie “diet” colas.

Meanwhile, younger generations started turning to their own new brands. And not just drinks. Instead of holding a Coke, increasingly they hold an iPhone. Where once it was hip to hang out at the Coke machine, or the fountain stand, now people would rather hang out at a Starbucks or Peet’s Coffee. Where once Coke was identified and matched the aspirations of the fast growing Boomer class, now it is replaced with a Prada handbag or other accessory from an LVMH branded luxury product.

Where once holding a Coke was a sign of being part of all that was good, now the product is largely passe. Trends have moved, and Coke didn’t. Coke leadership relied too much on its past, and failed to recognize that market shifts could affect even the #1 global brand. Coke leaders thought they would be forever relevant, just do more of what worked before. But they were wrong.

Unfortunately, CEO Muhtar Kent announced a series of changes that will most likely further hurt the Coca-Cola company rather than help it.

First, and foremost, like almost all CEOs facing an earnings problem the company will cut $3B in costs. The most short-term of short-term actions, which will do nothing to help the company find its way back toward being a prominent brand-leading icon. Cost cuts only further create a “hunker-down” mindset which causes managers to reduce risk, rather than look for breakthrough products and markets which could help the company regain lost ground. Cost cutting will only further cause remaining management to focus on defending the past business rather than finding a new future.

Second, Coca-Cola will sell off its bottlers. Interestingly, in the 1980s CEO Roberto Goizueta famously bought up the distributorships, and made a fortune for the company doing so. By the year 2000 he was honored, along with Jack Welch of GE, as being one of the top 2 CEOs of the century for his ability to create shareholder value. But now the current CEO is selling the bottling operations – in order to raise cash. Once again, when leadership can’t run a business that makes money they often sell off assets to generate cash and make the company smaller – none of which benefits shareholders.

Third, fire the Chief Marketing Officer. Of course, somebody has to be blamed! The guy who has done the most to bring Coca-Cola’s brand out of traditional advertising and promote it in an integrated manner across all media, including managing successful programs for the Olympics and World Cup, has to be held accountable. What’s missing in this action is that the big problem is leadership’s fixation with defending its Coke brand, rather than finding new growth businesses as the market moves away from carbonated soft drinks. And that is a problem that requires the CEO and his entire management team to step up their strategy efforts, not just fire the leader who has been updating the branding mechanisms.

Coca-Cola needs a significant strategy shift. Leadership focused too long on its aging brands, without putting enough energy into identifying trends and figuring out how to remain relevant. Now, people care a lot less about Coke than they did. They care more about other brands, like Apple. Globally. Unless there is a major shift in Coke’s strategy the company will continue to weaken along with its primary brand. That market shift has already happened, and it won’t stop.

For Coke to regain growth it needs a far different future which aligns with trends that now matter more to consumers. The company must bring forward products which excite people ,and with which they identify. And Coke’s leaders must move much harder into understanding shifts in media consumption so they can make their new brands as visible to newer generations as TV made Coke visible to Boomers.

Coke is far from a failed company, but after a decade of sales declines in its “core” business it is time leadership realizes takes this earnings announcement as a key indicator of the need to change. And not just simple things like costs. It must fundamentally change its strategy and markets or in another decade things will look far worse than today.

by Adam Hartung | Oct 21, 2014 | Current Affairs, Innovation, Leadership

“Where was the Board of Directors?”

That is one of the questions I am asked most frequently. And it’s a good one. Readers, and audiences, wonder how a well-educated and experienced Board could allow a company – like Blockbuster, Hostess, Radio Shack, Sears, Circuit City and Blackberry, to name a few – to fall into bankruptcy, or a situation where the future looks dismal, perhaps impossible.

Isn’t the Board accountable for company strategy, performance and the decisions made by the CEO? Perhaps, but they often haven’t acted like it.

Powerless Past

Historically Boards of Directors reviewed a company strategy once per year, and it was far from a discussion. The CEO, perhaps along with his/her top few executives, would present a multi-page document, attaching ample appendices including elaborate spreadsheets and charts. This would be a one-way presentation to the Board, overviewing recent performance, past strategy and management’s view of the future strategy.

There might have been polite discussion, but the Board only had one available action, either approve the strategy, or reject it. Given that Boards had no ability to create their own strategy, and rarely much data to contradict the mountain of statistics presented by management, the vote was a given – out came the “rubber stamp” of approval. All orchestrated by an “Imperial CEO” who rarely wanted discussion, or anything other than quick approval.

A Call For Change

Facing mounting investor concerns about strategic guidance and the Board’s role, the increasing involvement of activist investors willing to replace Board members, and the long arm of enhanced regulation the National Association of Corporate Directors (NACD) created a Blue Ribbon Commission to review the Board’s role in setting corporate strategy. Co-Chaired by Ray Gilmartin (former Chair and CEO of Becton Dickinson and Merck, Board member of Microsoft and General Mills, HBS ’68) and Maggie Wilderotter (Chair and CEO of Frontier Communications, Board member Procter & Gamble and Xerox) and containing 21 diverse business leaders, this commission just published “The NACD Blue Ribbon Commission Report on Strategy Development.”

This report makes 10 specific recommendations regarding Board involvement in corporate strategy, which in total represent a substantial change in how often, and how deeply, Boards discuss and alter strategy in conjunction with management. The report calls for greater accountability by the Board, increased transparency from management and the requirement for better strategy development.

A New, More Controversial Involvement by Boards of Directors

In an interview, Dr. Raetha King, Chair of NACD (former Board member Exxon Mobil, Wells Fargo, HB Fuller, Lenox Group and General Mills Foundation) said “it is time for Boards to change their approach regarding strategy formulation toward ‘shape and monitor.’ Boards must move from a passive role to a more active role. The Board must be fully engaged, at all times, with strategy.”

When asked what has prompted this significant recommendation, Dr. King went on to say “This report was deeply influenced by the external disruptions which are happening to companies on a regular basis in today’s dynamic markets. Boards are too often blindsided by external events, as is management. The solution is a fundamental change in the strategy process to engage the Board earlier, and more often. To have Boards participate in the strategy process, and not merely approve a finished product. The Board must become a strategic asset for the CEO and his executive team by engaging all members, and their cognitive diversity, for insight and direction.”

Recognizing and Managing Disruption

Co-chair Ray Gilmartin has been a professor at the Harvard Business School, and a colleague of fellow professor and famed innovation guru Dr. Clayton Christensen. He has observed how disruptive innovations have affected many companies, and has asked Dr. Christensen to provide Boards with advice on how to avoid becoming stuck in the “Innovator’s Dilemma.” Mr. Gilmartin offered “The NACD’s Blue Ribbon Commission report on strategy is intended to help corporate directors and their boards prepare for the unpredictable, even the unthinkable. More specifically, the report is intended to evolve director’s strategy development role from the typical ‘review and concur’ to a higher level of year-round engagement in the strategy development process.”

This is a remarkable change in Board involvement, well beyond anything previously recommended by any association or other body which works with corporate Boards. And the impact should be widely felt, as NACD has 14,000 members, all belonging to Boards. By recommending that Boards re-allocate their time to spend more on strategy discussion, and less on historical results and reviews of well-known practices, this commission is pushing for a sea change in the strategy process.

Changed Role for the CEO, and the Board

Co-chair Maggie Wilderotter has the view not only of an outside director, but as someone currently holding both CEO and Chair positions in a company. She completely concurred with her commission colleagues. In our interview she commented “Historically, strategy was not dynamic. Now it must be, due to so many marketplace changes happening so quickly. It is critical that the CEO utilize the Board to re-assess strategy at each Board meeting so as to better prepare for changes and avoid incurring any additional marketplace risk.”

She continued “The new best practice, today, is for management to draft the strategy, but not finalize it. Options must be posited and discussed. Yes, the CEO must own the strategy, and the strategy development process. And part of that process is to drive discussion with not only internal management but external leaders on the Board. It is critical companies track more trends from outside the company, add more external inputs to the data, and be increasingly aware of how the external world impacts the company. Good execution today involves connecting internal metrics to external markets.”

This will involve quite a bit of change in Board dynamics. Many CEOs, as mentioned above, may not be prepared for such a radical shift in the strategy development process. To address this Ms. Wilderotter recommends “Board members must pressure the Chairman and/or Lead Director for updates on strategy before documents are made final, and before final decisions are made. Members must resist accepting final documents, and insist on receiving interim information. Members must constantly push for management to supply not only internal information, but external data on trends, competitors, customers and all factors that could impact future performance. There must be a proactive conversation on the new expectations directors have about management engaging them in the strategy development process. And Board members must insist on Executive Sessions, apart from management, to discuss strategy amongst themselves and develop feedback for the CEO.”

The report pulls no punches in its strong recommendations for changing the Board’s involvement in strategy. And the degree to which the report, and its authors, identify the importance of disruptive change on company performance today is eye opening. The report’s first recommendation sets the tone for significant change:

“Expect change and understand how it may affect the company’s current strategic course, potentially undermining the fundamental assumptions on which the strategy rests.”

Is this the end of the “Imperial CEO?” Readers know I have long called for greater transparency and more Board involvement in challenging CEOs where the strategy does not align with market realities. This report seeks the same thing. Boards can no longer allow the failure of management, or overly rely on a dictatorial CEO, on something as important as corporate strategy. They owe too much to the investors, employees, suppliers and communities in which their organizations operate.

As readers of my book and this blog know, this has long been my mantra. Like Dr. Christensen, I too encourage leaders to open their eyes to the extent which disruption affects their organizations in my columns, my keynote speeches and workshops. No longer is excellent execution enough. In a world where technologies, regulations, customers, products and competitors change so quickly strategy must be reviewed and updated constantly. And this report, from a noteworthy organization and blue ribbon panel, is a clear call for Boards to sink their teeth deeper into strategy.

All Board members, and people who want to be on Boards, should seek out a copy of this report, read it and share it with executives and Board members across your networks. These are recommendations which can have a profound impact on future performance in our rapidly changing world.

[Update 10-28-2014 — NACD has released a summary of the report. Follow this link to read all 10 recommendations and become better informed.]

by Adam Hartung | Oct 15, 2014 | Current Affairs, Defend & Extend, Innovation, Leadership

The Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA) is down 400 points today. Down 8% since its high 3 weeks ago, and now showing no gains for the entire year.

Oh my!

There seems little immediate explanation for the fast drop. When major financial news outlets say it is caused by Ebola fears you can be assured those being asked “why” are clutching at straws. They have no clear explanation. This could be nothing more than a 10% correction, a short-term break in the long-term bull which has gone on for a remarkable 3 years.

But, investors are not out of the woods. Will the market continue to even greater highs? Will this Bull market continue for many more months?

There is at least one good reason investors should be concerned.

For the last decade, corporations have been about the biggest buyers of equities. Since 1998 85% of all corporate earnings have gone into share buyback programs. Buybacks do not add value to a company, they merely reduce the number of shares. By reducing the number of outstanding shares, earnings per share (EPS) can go up, even if earnings do not go up. But reducing the denominator the answer increases, even if the numerator does not change – or goes up only slightly. Thus per share earnings have increased, on average, 6.2% quarterly – more than double the revenue increase of only 2.6%. All artificial growth – not a true increase in corporate performance.

In 2014 95% of S&P 500 corporate earnings will go toward buybacks and dividends – in effect increasing investor returns while doing nothing to make the companies better. In the 1st quarter money paid to investors exceeded S&P 500 profits, and likely will do so again in the 3rd quarter. All of which props up stocks in the short-term, but removes cash from the companies. Cash which could be used to invest in growing revenues long-term.

This is not new. In the last decade, cash for buybacks has doubled. Today, 30% of free cash flow goes into stock repurchases, a rate double that of 2002.

Meanwhile investment in plant and equipment has declined from over 50% of cash flow to under 40%. Today the average age of plant and equipment in the USA is 22 years – the oldest it has been since 1956! In an era of almost free money – with interest rates in low single digits and often less than inflation – corporations are taking on debt NOT to invest in growth, but rather to simply pay out more to shareholders in efforts to prop up stock prices. And they’ve done it now for so long – over a decade – that the short-term has become the long-term, and there is precious little invested base from which future revenues and profits can grow.

Leaders for the past several years have failed their investors by not investing cash flow in innovation for long-term growth. Instead of new products creating new markets, the only innovations being funded have been focused solely on defending and extending past product sales. With an inordinate fear of risk, and a complete lack of future vision, what passes for innovation are attempts to sustain the old stuff rather than create something new.

For example, P&G’s leaders gave investors the “Basic” line of products. These were literally less good products, a throwback to earlier quality levels, repackaged and sold at a lower price. The last really “new” product from P&G was the Swiffer mop – and that was back in 1999. Since then we’ve had what seems to be infinite variations of that product, all intended to extend its life. Where’s the new “great thing” that will jump revenues and sustain profits for years into the future?

There are exceptions to this generalization. Of course Facebook is changing media and advertising, while Netflix is redeveloping how we enjoy entertainment. Amazon has us buying on-line instead of in retail stores, and wondering if we’ll someday receive same-day shipping via drones. And Apple has moved us into the world of apps encouraging us to buy smartphones and tablets while dumping land-lines, cell phones and PCs. So there are some serious innovators out there.

But, for long-term investors overall, there is a big reason to worry. This DJIA drop may be merely a “normal 10% correction.” But, equities cannot go up forever on declining cash flow from ancient investments of previous leaders and interest-free debt accumulation. For equities to continue their upward trajectory at some time companies have to launch new products, create new markets and generate sustainable long-term profits. In other than a handful of noteworthy companies, there isn’t much of this kind of investment happening today – or over the last 10-15 years.

Eventually, costs of capital will go up. And cash flow from old investments will go down. If there aren’t real sales growth opportunities there could be declining real profits. Without buybacks to feed the bull, a raging bear could overtake the scene.

Oh my.

by Adam Hartung | Oct 6, 2014 | Current Affairs, In the Swamp, In the Whirlpool, Leadership, Web/Tech

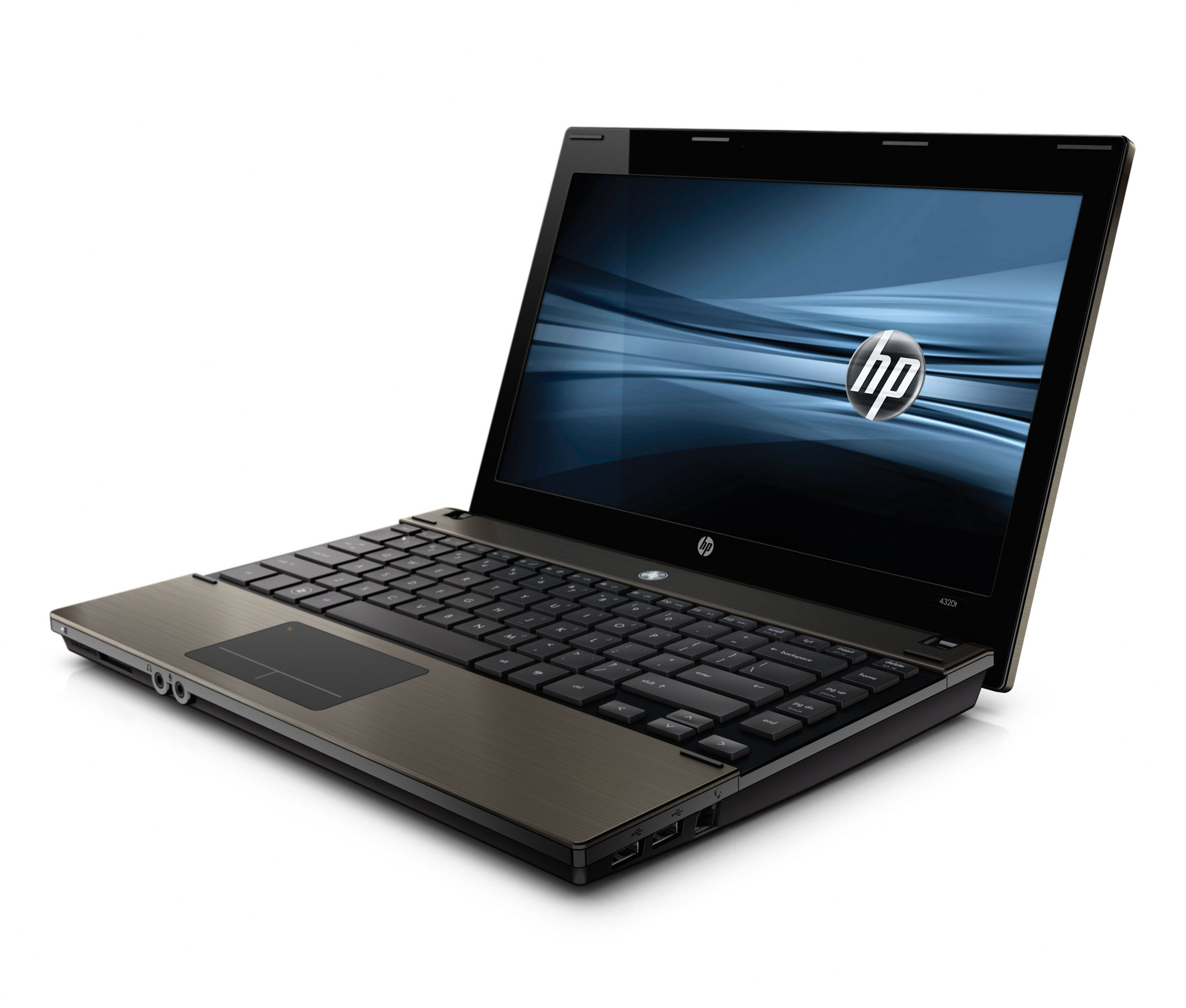

Hewlett Packard is splitting in two. Do you find yourself wondering why? You aren’t alone.

Hewlett Packard is nearly 75 years old. One of the original “silicone valley companies,” it started making equipment for engineers and electronic technicians long before computers were every day products. Over time HP’s addition of products like engineering calculators moved it toward more consumer products. And eventually HP became a dominant player in printers. All of these products were born out of deep skills in R&D, engineering and product development. HP had advantages because its products were highly desirable and unique, which made it nicely profitable.

But along came a CEO named Carly Fiorina, and she decided HP needed to grow much bigger, much more quickly. So she bought Compaq, which itself had bought Digital Equipment, so HP could sell Wintel PCs. PCs were a product in which HP had no advantage. PC production had always been an assembly operation of other companies’ intellectual property. It had been a very low margin, brutally difficult place to grow unless one focused on cost lowering rather than developing intellectual capital. It had nothing in common with HP’s business.

To fight this new margin battle HP replaced Ms. Fiorina with Mark Hurd, who recognized the issues in PC manufacturing and proceeded to gut R&D, product development and almost every other function in order to push HP into a lower cost structure so it could compete with Dell, Acer and other companies that had no R&D and cultures based on cost controls. This led to internal culture conflicts, much organizational angst and eventually the ousting of Mr. Hurd.

But, by that time HP was a company adrift with no clear business model to help it have a sustainably profitable future.

Now HP is 4 years into its 5 year turnaround plan under Meg Whitman’s leadership. This plan has made HP much smaller, as layoffs have dominated the implementation. It has weakened the HP brand as no important new products have been launched, and the gutted product development capability is still no closer to being re-established. And PC sales have stagnated as mobile devices have taken center stage – with HP notably weak in mobile products. The company has drifted, getting no better and showing no signs of re-developing its historical strengths.

So now HP will split into two different companies. Following the old adage “if you can’t dazzle ’em with brilliance, baffle ’em with bulls**t.” When all else fails, and you don’t know how to actually lead a company, then split it into pieces, push off the parts to others to manage and keep at least one CEO role for yourself.

Let’s not forget how this mess was created. It was a former CEO who decided to expand the company into an entirely different and lower margin business where the company had no advantage and the wrong business model. And another that destroyed long-term strengths in innovation to increase short-term margins in a generic competition. And then yet a third who could not find any solution to sustainability while pushing through successive rounds of lay-offs.

This was all value destruction created by the persons at the top. “Strategic” decisions made which, inevitably, hurt the organization more than helped it. Poorly thought through actions which have had long-term deleterious repercussions for employees, suppliers, investors and the communities in which the businesses operate.

The game of musical chairs has been very good for the CEOs who controlled the music. They were paid well, and received golden handshakes. They, and their closest reports, did just fine. But everyone else….. well…..

by Adam Hartung | Sep 30, 2014 | Current Affairs, Disruptions, In the Rapids, Innovation, Leadership, Web/Tech

Will the new Apple Pay product, revealed on iPhone 6 devices, succeed? There have been many entries into the digital mobile payments business, such as Google Wallet, Softcard (which had the unfortunate initial name of ISIS,) Square and Paypal. But so far, nobody has really cracked the market as Americans keep using credit cards, cash and checks.

But that looks like it might change, and Apple has a pretty good chance of making Apple Pay a success.

First, a look at some critical market changes. For decades we all thought credit card purchases were secure. But that changed in 2013, and picked up steam in 2014. With regularity we’ve heard about customer credit card data breaches at various retailers and restaurants. Smaller retailers like Shaw’s, Star Markets and Jewel caused some mild concern. But when top tier retailers like Target and Home Depot revealed security problems, across millions of accounts, people really started to notice. For the first time, some people are thinking an alternative might be a good idea, and they are considering a change.

In other words, there is now an underserved market. For a long time people were very happy using credit cards. But now, they aren’t as happy. There are people, still a minority, who are actively looking for an alternative to cash and credit cards. And those people now have a need that is not fully met. That means the market receptivity for a mobile payment product has changed.

Second let’s look at how Paypal became such a huge success fulfilling an underserved market. When people first began on-line buying transactions were almost wholly credit cards. But some customers lacked the ability to use credit cards. These folks had an underserved need, because they wanted to buy on-line but had no payment method (mailing checks or cash was risky, and COD shipments were costly and not often supported by on-line vendors.) Paypal jumped into that underserved market.

Quickly Paypal tied itself to on-line vendors, asking them to support their product. They went less to people who were underserved, and mostly to the infrastructure which needed to support the product. By encouraging the on-line retailers they could expand sales with Paypal adoption, Paypal gathered more and more sites. The 2002 acquisition by eBay was a boon, as it truly legitimized Paypal in minds of consumers and smaller on-line retailers.

After filling the underserved market, Paypal expanded as a real competitor for credit cards by adding people who simply preferred another option. Today Paypal accounts for $1 of every $6 spent on-line, a dramatic statistic. There are 153million Paypal digital wallets, and Paypal processes $203B of payments annually. Paypal supports 26 currencies, is in 203 markets, has 15,000 financial institution partners – all creating growth last year of 19%. A truly outstanding success story.

Back to traditional retail. As mentioned earlier, there is an underserved market for people who don’t want to use cash, checks or credit cards. They seek a solution. But just as Paypal had to obtain the on-line retailer backing to acquire the end-use customer, mobile payment company success relies on getting retailers to say they take that company’s digital mobile payment product.

Here is where Apple has created an advantage. Few end-use customers are terribly aware of retail beacons, the technology which has small (sometimes very small) devices placed in a store, fast food outlet, stadium or other environment which sends out signals to talk to smartphones which are in nearby proximity. These beacons are an “inside retail” product that most consumer don’t care about, just like they don’t really care about the shelving systems or price tag holders in the store.

Launched with iOS 7, Apple’s iBeacon has become the leader in this “recognize and push” technology. Since Apple installed Beacons in its own stores in December, 2013 tens of thousands of iBeacons have been installed in retailers and other venues. Macy’s alone installed 4,000 in 2014. Increasingly, iBeacons are being used by retailers in conjunction with consumer goods manufacturers to identify who is shopping, what they are buying, and assist them with product information, coupons and other purchase incentives.

Thus, over the last year Apple has successfully been courting the retailers, who are the infrastructure for mobile payments. Now, as the underserved payment issue comes to market it is natural for retailers to turn to the company with which they’ve been working on their “infrastructure” products.

Apple has an additional great benefit because it has by far the largest installed base of smartphones, and its products are very consistent. Even though Android is a huge market, and outsells iOS, the platform is not consistent because Android on Samsung is not like Android on Amazon’s Fire, for example. So when a retailer reaches out for the alternative to credit cards, Apple can deliver the largest number of users. Couple that with the internal iBeacon relationship, and Apple is really well positioned to be the first company major retailers and restaurants turn to for a solution – as we’ve already seen with Apple Pay’s acceptance by Macy’s, Bloomingdales, Duane Reed, McDonald’s Staples, Walgreen’s, Whole Foods and others.

This does not guarantee Apple Pay will be the success of Paypal. The market is fledgling. Whether the need is strong or depth of being underserved is marked is unknown. How consumers will respond to credit card use and mobile payments long-term is impossible to gauge. How competitors will react is wildly unpredictable.

But, Apple is very well positioned to win with Apple Pay. It is being introduced at a good time when people are feeling their needs are underserved. The infrastructure is primed to support the product, and there is a large installed base of users who like Apple’s mobile products. The pieces are in place for Apple to disrupt how we pay for things, and possibly create another very, very large market. And Apple’s leadership has a history of successfully managing disruptive product launches, as we’ve seen in music (iPod,) mobile phones (iPhone) and personal technology tools (iPad.)

by Adam Hartung | Sep 17, 2014 | Current Affairs, Disruptions, In the Whirlpool, Leadership, Lock-in

Sony was once the leader in consumer electronics. A brand powerhouse who’s products commanded a premium price and were in every home. Trinitron color TVs, Walkman and Discman players, Vaio PCs. But Sony has lost money for all but one quarter across the last 6 years, and company leaders just admitted the company will lose over $2B this year and likely eliminate its dividend.

McDonald’s created something we now call “fast food.” It was an unstoppable entity that hooked us consumers on products like the Big Mac, Quarter Pounder and Happy Meal. An entire generation was seemingly addicted to McDonald’s and raised their families on these products, with favorable delight for the ever cheery, clown-inspired spokesperson Ronald McDonald. But now McDonald’s has hit a growth stall, same-store sales are down and the Millenial generation has turned its nose up creating serious doubts about the company’s future.

Radio Shack was the leader in electronics before we really had a consumer electronics category. When we still bought vacuum tubes to repair radios and TVs, home hobbyists built their own early versions of computers and video games worked by hooking them up to TVs (Atari, etc.) Radio Shack was the place to go. Now the company is one step from bankruptcy.

Sears created the original non-store shopping capability with its famous catalogs. Sears went on to become a Dow Jones Industrial Average component company and the leading national general merchandise retailer with powerhouse brands like Kenmore, Diehard and Craftsman. Now Sears’ debt has been rated the lowest level junk, it hasn’t made a profit for 3 years and same store sales have declined while the number of stores has been cut dramatically. The company survives by taking loans from the private equity firm its Chairman controls.

How in the world can companies be such successful pioneers, and end up in such trouble?

Markets shift. Things in the world change. What was a brilliant business idea loses value as competitors enter the market, new technologies and solutions are created and customers find they prefer alternatives to your original success formula. These changed markets leave your company irrelevant – and eventually obsolete.

Unfortunately, we’ve trained leaders over the last 60 years how to be operationally excellent. In 1960 America graduated about the same number of medical doctors, lawyers and MBAs from accredited, professional university programs. Today we still graduate about the same number of medical doctors every year. We graduate about 6 times as many lawyers (leading to lots of jokes about there being too many lawyers.) But we graduate a whopping 30 times as many MBAs. Business education skyrocketed, and it has become incredibly normal to see MBAs at all levels, and in all parts, of corporations.

The output of that training has been a movement toward focusing on accounting, finance, cost management, supply chain management, automation — all things operational. We have trained a veritable legion of people in how to “do things better” in business, including how to measure costs and operations in order to make constant improvements in “the numbers.” Most leaders of publicly traded companies today have a background in finance, and can discuss the P&L and balance sheets of their companies in infinite detail. Management’s understanding of internal operations and how to improve them is vast, and the ability of leaders to focus an organization on improving internal metrics is higher than ever in history.

But none of this matters when markets shift. When things outside the corporation happen that makes all that hard work, cost cutting, financial analysis and machination pretty much useless. Because today most customers don’t really care how well you make a color TV or physical music player, since they now do everything digitally using a mobile device. Nor do they care for high-fat and high-carb previously frozen food products which are consistently the same because they can find tastier, fresher, lighter alternatives. They don’t care about the details of what’s inside a consumer electronic product because they can buy a plethora of different products from a multitude of suppliers with the touch of a mobile device button. And they don’t care how your physical retail store is laid out and what store-branded merchandise is on the shelves because they can shop the entire world of products – and a vast array of retailers – and receive deep product reviews instantaneously, as well as immediate price and delivery information, from anywhere they carry their phone – 24×7.

“Get the assumptions wrong, and nothing else matters” is often attributed to Peter Drucker. You’ve probably seen that phrase in at least one management, convention or motivational presentation over the last decade. For Sony, McDonald’s, Radio Shack and Sears the assumptions upon which their current businesses were built are no longer valid. The things that management assumed to be true when the companies were wildly profitable 2 or 3 decades ago are no longer true. And no matter how much leadership focuses on metrics, operational improvements and cost cutting – or even serving the remaining (if dwindling) current customers – the shift away from these companies’ offerings will not stop. Rather, that shift is accelerating.

It has been 80 years since Harvard professor Joseph Schumpeter described “creative destruction” as the process in which new technologies obsolete the old, and the creativity of new competitors destroys the value of older companies. Unfortunately, not many CEOs are familiar with this concept. And even fewer ever think it will happen to them. Most continue to hope that if they just make a few more improvements their company won’t really become obsolete, and they can turn around their bad situation.

For employees, suppliers and investors such hope is a weak foundation upon which to rely for jobs, revenues and returns.

According to the management gurus at McKinsey, today the world population is getting older. Substantially so. Almost no major country will avoid population declines over next 20 years, due to low birth rates. Simultaneously, better healthcare is everywhere, and every population group is going to live a whole lot (I mean a WHOLE LOT) longer. Almost every product and process is becoming digitized, and any process which can be done via a computer will be done by a computer due to almost free computation. Global communication already is free, and the bandwidth won’t stop growing. Secrets will become almost impossible to keep; transparency will be the norm.

These trends matter. To every single business. And many of these trends are making immediate impacts in 2015. All will make a meaningful impact on practically every single business by 2020. And these trends change the assumptions upon which every business – certainly every business founded prior to 2000 – demonstrably.

Are you changing your assumptions, and your business, to compete in the future? If not, you could soon look at your results and see what the leaders at Sony, McDonald’s, Radio Shack and Sears are seeing today. That would be a shame.